Portugal

Portugal (Portuguese pronunciation: [puɾtuˈɣal] ⓘ), officially the Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: República Portuguesa [ʁɛˈpuβlikɐ puɾtuˈɣezɐ]),[note 3] is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the macaronesian archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira. It features the westernmost point in continental Europe, and its Iberian portion is bordered to the west and south by the Atlantic Ocean and to the north and east by Spain, the sole country to have a land border with Portugal. Its archipelagos form two autonomous regions with their own regional governments. In the mainland, Alentejo region occupies the biggest area but is one of the regions in Europe with a lower population density. Lisbon is the capital and largest city by population, being also the main spot for tourists alongside Porto and Algarve.

Portuguese Republic | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: A Portuguesa "The Portuguese" | |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital and largest city | Lisbon 38°46′N 9°9′W |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised regional languages | Mirandese[note 1] |

| Nationality (2022)[3] |

|

| Religion (2021)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Portuguese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic[5] |

| Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa | |

| António Costa | |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Republic |

| Establishment | |

| 868 | |

| 1095 | |

| 24 June 1128 | |

• Kingdom | 25 July 1139 |

| 5 October 1143 | |

| 1 December 1640 | |

| 23 September 1822 | |

• Republic | 5 October 1910 |

| 25 April 1974 | |

| 25 April 1976[note 2] | |

| 1 January 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 92,225.2 km2 (35,608.3 sq mi)[6] (109th) |

• Water (%) | 1.2 (2015)[7] |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 113.5/km2 (294.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 38th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC (WET) UTC−1 (Atlantic/Azores) |

| UTC+1 (WEST) UTC (Atlantic/Azores) | |

| Note: Continental Portugal and Madeira use WET/WEST; the Azores are 1 hour behind. | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +351 |

| ISO 3166 code | PT |

| Internet TLD | .pt |

| |

One of the oldest countries in Europe, its territory has been continuously settled, invaded and fought over since prehistoric times. The territory was inhabited by the Celtic and Iberian peoples, such as the Lusitanians, the Gallaecians, the Celtici, Turduli, and the Conii. These peoples had some commercial and cultural contact with Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Carthaginians. It was later ruled by the Romans, followed by the invasions of Germanic peoples (most prominently, the Suebi and the Visigoths) together with the Alans, and later the Moors, who were eventually expelled during the Reconquista. Founded first as a county within the Kingdom of León in 868, the country officially gained its independence as the Kingdom of Portugal with the Treaty of Zamora in 1143.[13]

Portugal made numerous discoveries and maritime explorations outside the Mediterranean and by the 15th and 16th centuries established one of the longest-lived maritime and commercial empires, becoming one of the main economic and political powers of the time.[14] At the end of the 16th century, Portugal fought Spain in a war over the succession to the Portuguese crown, leading to the Iberian Union. The Portuguese Restoration War re-instated the House of Braganza in 1640 after a period of substantial loss to Portugal.[15]

By the early 19th century, the accumulative crisis, events such as the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the country's occupation during the Napoleonic Wars, and the resulting independence of Brazil in 1822 led to a marked decay of Portugal's prior opulence.[16] This was followed by the civil war between liberal constitutionalists and conservative absolutists over royal succession, which lasted from 1828 to 1834. The 1910 revolution deposed Portugal's centuries-old monarchy, and established the democratic but unstable Portuguese First Republic, later being superseded by the Estado Novo (New State) authoritarian regime. Democracy was restored after the Carnation Revolution (1974), ending the Portuguese Colonial War and eventually losing its remaining colonial possessions.

Portugal has left a profound cultural, architectural and linguistic influence across the globe, with a legacy of around 250 million Portuguese speakers around the world. It is a developed country with an advanced economy. A member of the United Nations, the European Union, the Schengen Area and the Council of Europe (CoE), Portugal was also one of the founding members of NATO, the eurozone, the OECD, and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.

Etymology

The word Portugal derives from the combined Roman-Celtic place name Portus Cale;[17][18] a settlement where present-day's conurbation of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia (or simply, Gaia) stand, along the banks of River Douro in the north of what is now Portugal. The name of Porto stems from the Latin word for port or harbour, portus, with the second element Cale's meaning and precise origin being less clear. The mainstream explanation points to an ethnonym derived from the Callaeci also known as Gallaeci peoples, who occupied the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula.[19] The names Cale and Callaici are the origin of today's Gaia and Galicia.[20][21]

Another theory proposes that Cale or Calle is a derivation of the Celtic word for 'port', like the Irish caladh or Scottish Gaelic cala. These explanations, would require the pre-Roman language of the area to have been a branch of Q-Celtic, which is not generally accepted because the region's pre-Roman language was Gallaecian. However, scholars like Jean Markale and Tranoy propose that the Celtic branches all share the same origin, and placenames such as Cale, Gal, Gaia, Calais, Galatia, Galicia, Gaelic, Gael, Gaul (Latin: Gallia),[22] Wales, Cornwall, Wallonia and others all stem from one linguistic root.[20][23][24]

A further explanation proposes Gatelo as having been the origin of present-day Braga, Santiago de Compostela, and consequently the wider regions of Northern Portugal and Galicia.[25] A different theory has it that Cala was the name of a Celtic goddess (drawing a comparison with the Gaelic Cailleach, a supernatural hag). Further still, some French scholars believe the name may have come from Portus Gallus,[26] the port of the Gauls or Celts.

Around 200 BC, the Romans took the Iberian Peninsula from the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. In the process they conquered Cale, renaming it Portus Cale ('Port of Cale') and incorporating it in the province of Gaellicia with its capital in Bracara Augusta (modern day Braga, Portugal). During the Middle Ages, the region around Portus Cale became known by the Suebi and Visigoths as Portucale. The name Portucale evolved into Portugale during the 7th and 8th centuries, and by the 9th century, that term was used extensively to refer to the region between the rivers Douro and Minho. By the 11th and 12th centuries, Portugale, Portugallia, Portvgallo or Portvgalliae was already referred to as Portugal.

The 14th-century Middle French name for the country, Portingal, which added an intrusive /n/ sound through the process of excrescence, spread to Middle English.[27] Middle English variant spellings included Portingall, Portingale,[note 4] Portyngale and Portingaill.[27][29] The spelling Portyngale is found in Chaucer's Epilogue to the Nun's Priest's Tale. These variants survive in the Torrent of Portyngale, a Middle English romance composed around 1400, and "Old Robin of Portingale", an English Child ballad. Portingal and variants were also used in Scots[27] and survive in the Cornish name for the country, Portyngal.

History

Prehistory

The early history of Portugal is shared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula located in southwestern Europe. The name of Portugal derives from the joined Romano-Celtic name Portus Cale. The region was settled by Pre-Celts and Celts, giving origin to peoples like the Gallaeci, Lusitanians,[30] Celtici and Cynetes (also known as Conii).[31] Some coastal areas were visited by Phoenicians-Carthaginians and Ancient Greeks. It was incorporated in the Roman Republic dominions as Lusitania and part of Gallaecia, after 45 BC until 298 AD.

The region of present-day Portugal was inhabited by Neanderthals and then by Homo sapiens, who roamed the border-less region of the northern Iberian peninsula.[32] These were subsistence societies and although they did not establish prosperous settlements, they did form organized societies. Neolithic Portugal experimented with domestication of herding animals, the raising of some cereal crops and fluvial or marine fishing.[32]

.jpg.webp)

It is believed by some scholars that early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Celts invaded Portugal from Central Europe and inter-married with the local populations, forming different tribes.[33] Another theory suggests that Celts inhabited western Iberia / Portugal well before any large Celtic migrations from Central Europe.[34] In addition, a number of linguists expert in ancient Celtic have presented compelling evidence that the Tartessian language, once spoken in parts of SW Spain and SW Portugal, is at least proto-Celtic in structure.[35]

Modern archaeology and research shows a Portuguese root to the Celts in Portugal and elsewhere.[36] During that period and until the Roman invasions, the Castro culture (a variation of the Urnfield culture also known as Urnenfelderkultur) was prolific in Portugal and modern Galicia.[37][38][21] This culture, together with the surviving elements of the Atlantic megalithic culture[39] and the contributions that come from the more Western Mediterranean cultures, ended up in what has been called the Cultura Castreja or Castro Culture.[40][41] This designation refers to the characteristic Celtic populations called 'dùn', 'dùin' or 'don' in Gaelic and that the Romans called castrae in their chronicles.[42]

Based on the Roman chronicles about the Callaeci peoples, along with the Lebor Gabála Érenn[43] narrations and the interpretation of the abundant archaeological remains throughout the northern half of Portugal and Galicia, it is possible to infer that there was a matriarchal society, with a military and religious aristocracy probably of the feudal type. The figures of maximum authority were the chieftain (chefe tribal), of military type and with authority in his Castro or clan, and the druid, mainly referring to medical and religious functions that could be common to several castros. The Celtic cosmogony remained homogeneous due to the ability of the druids to meet in councils with the druids of other areas, which ensured the transmission of knowledge and the most significant events.

The first documentary references to Castro society are provided by chroniclers of Roman military campaigns such as Strabo, Herodotus and Pliny the Elder among others, about the social organization, and describing the inhabitants of these territories, the Gallaeci of Northern Portugal as:

"A group of barbarians who spend the day fighting and the night eating, drinking and dancing under the moon."

There were other similar tribes, and chief among them were the Lusitanians; the core area of these people lay in inland central Portugal, while numerous other related tribes existed such as the Celtici of Alentejo, and the Cynetes or Conii of the Algarve. Among the tribes or sub-divisions were the Bracari, Coelerni, Equaesi, Grovii, Interamici, Leuni, Luanqui, Limici, Narbasi, Nemetati, Paesuri, Quaquerni, Seurbi, Tamagani, Tapoli, Turduli, Turduli Veteres, Turduli Oppidani, Turodi, and Zoelae. A few small, semi-permanent, commercial coastal settlements (such as Tavira) were also founded in the Algarve region by Phoenicians–Carthaginians.

Roman Lusitania and Gallaecia

Romans first invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 219 BC. The Carthaginians, Rome's adversary in the Punic Wars, were expelled from their coastal colonies. During the last days of Julius Caesar, almost the entire peninsula was annexed to the Roman Republic.

The Roman conquest of what is now part of Portugal took almost two hundred years and took many lives of young soldiers and the lives of those who were sentenced to a certain death in the slave mines when not sold as slaves to other parts of the empire. Roman occupation suffered a severe setback in 155 BC, when a rebellion began in the north. The Lusitanians and other native tribes, under the leadership of Viriathus,[44][45] wrested control of all of western Iberia.

Rome sent numerous legions and its best generals to Lusitania to quell the rebellion, but to no avail – the Lusitanians kept conquering territory. The Roman leaders decided to change their strategy. They bribed Viriathus's allies to kill him. In 139 BC, Viriathus was assassinated and Tautalus became leader of the Lusitanians.

Rome installed a colonial regime. The complete Romanization of Lusitania only took place in the Visigothic era.

In 27 BC, Lusitania gained the status of Roman province. Later, a northern province of Lusitania was formed, known as Gallaecia, with capital in Bracara Augusta, today's Braga.[46] There are still many ruins of castros (hill forts) throughout modern Portugal and remains of the Castro culture. Some urban remains are quite large, like Conímbriga and Mirobriga. The former, beyond being one of the largest Roman settlements in Portugal, is also classified as a National Monument. Conímbriga lies 16 kilometres (10 miles) from Coimbra, which in turn was the ancient Aeminium. The site also has a museum that displays objects found by archaeologists during their excavations.

Several works of engineering, such as baths, temples, bridges, roads, circuses, theatres and laymen's homes are preserved throughout the country. Coins, some coined in Lusitanian land, as well as numerous pieces of ceramics, were also found. Contemporary historians include Paulus Orosius (c. 375–418)[47] and Hydatius (c. 400–469), bishop of Aquae Flaviae, who reported on the final years of the Roman rule and arrival of the Germanic tribes.

Germanic kingdoms: Suebi and Visigoths

In the early 5th century, Germanic tribes, namely the Suebi[48] and the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) together with their allies, the Sarmatians and Alans invaded the Iberian Peninsula where they would form their kingdom. The Kingdom of the Suebi[49] was the Germanic post-Roman kingdom, established in the former Roman provinces of Gallaecia-Lusitania. 5th-century vestiges of Alan settlements were found in Alenquer (from old Germanic Alan kerk, temple of the Alans), Coimbra and Lisbon.[50]

About 410 and during the 6th century it became a formally declared Kingdom of the Suebi,[49][48] where king Hermeric made a peace treaty with the Gallaecians before passing his domains to Rechila, his son. In 448 Rechila died, leaving the state in expansion to Rechiar. After the defeat against the Visigoths, the Suebian kingdom was divided, with Frantan and Aguiulfo ruling simultaneously. Both reigned from 456 to 457, the year in which Maldras (457–459) reunified the kingdom. He was assassinated after a failed Roman-Visigothic conspiracy. Although the conspiracy did not achieve its true purposes, the Suebian Kingdom was again divided between two kings: Frumar (Frumario 459–463) and Remismund (Remismundo, son of Maldras) (459–469) who would re-reunify his father's kingdom in 463. He would be forced to adopt Arianism in 465 due to the Visigoth influence. By 500, the Visigothic Kingdom had been installed in Iberia, it was based in Toledo and advancing westwards. They became a threat to the Suebian rule. After the death of Remismund in 469 a dark period set in, where virtually all written texts and accounts disappear. This period lasted until 550. The only thing known about this period is that Theodemund (Teodemundo) most probably ruled the Suebians. The dark period ended with the reign of Karriarico (550–559) who reinstalled Catholic Christianity in 550. He was succeeded by Theodemar (559–570) during whose reign the 1st Council of Braga (561) was held.

The councils represented an advance in the organization of the territory (paroeciam suevorum (Suebian parish) and the Christianization of the pagan population (De correctione rusticorum) under the auspices of Saint Martin of Braga (São Martinho de Braga).[51]

After the death of Teodomiro, Miro (570–583) was his successor. During his reign, the 2nd Council of Braga (572) was held. The Visigothic civil war began in 577. Miro intervened. Later in 583 he also organized an unsuccessful expedition to reconquer Seville. During the return from this failed operation Miro died.

In the Suebian Kingdom many internal struggles continued to take place. Eborico (Eurico, 583–584) was dethroned by Andeca (Audeca 584–585), who failed to prevent the Visigothic invasion led by Leovigildo. The Visigothic invasion, completed in 585, turned the once rich and fertile kingdom of the Suebi into the sixth province of the Gothic kingdom.[52] Leovigild was crowned King of Gallaecia, Hispania and Gallia Narbonensis.

For the next 300 years and by the year 700, the entire Iberian Peninsula was ruled by the Visigoths.[53][54][55][56][57] Under the Visigoths, Gallaecia was a well-defined space governed by a doge of its own. Doges at this time were related to the monarchy and acted as princes in all matters. Both 'governors' Wamba and Wittiza (Vitiza) acted as doge (they would later become kings in Toledo). These two became known as the 'vitizians', who headquartered in the northwest and called on the Arab invaders from the South to be their allies in the struggle for power in 711. King Roderic (Rodrigo) was killed while opposing this invasion, thus becoming the last Visigothic king of Iberia. From the various Germanic groups who settled in western Iberia, the Suebi left the strongest lasting cultural legacy in what is today Portugal, Galicia and western fringes of Asturias.[58][59][60] According to Dan Stanislawski, the Portuguese way of living in regions North of the Tagus is mostly inherited from the Suebi, in which small farms prevail, distinct from the large properties of Southern Portugal. Bracara Augusta, the modern city of Braga and former capital of Gallaecia, became the capital of the Suebi.[51] Apart from cultural and some linguistic traces, the Suebians left the highest Germanic genetic contribution of the Iberian Peninsula in Portugal and Galicia.[61] Orosius, at that time resident in Hispania, shows a rather pacific initial settlement, the newcomers working their lands[62] or serving as bodyguards of the locals.[63] Another Germanic group that accompanied the Suebi and settled in Gallaecia were the Buri. They settled in the region between the rivers Cávado and Homem, in the area known as Terras de Bouro (Lands of the Buri).[64]

Islamic period and the Reconquista

Today's continental Portugal, along with most of modern Spain, was part of al-Andalus between 726 and 1249, following the Umayyad Caliphate conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. This rule lasted from some decades in the North to five centuries in the South.[65]

After defeating the Visigoths in only a few months, the Umayyad Caliphate started expanding rapidly in the peninsula. Beginning in 726, the land that is now Portugal became part of the vast Umayyad Caliphate's empire of Damascus, which stretched from the Indus river in the Indian sub-continent up to the South of France, until its collapse in 750. That year the west of the empire gained its independence under Abd-ar-Rahman I with the establishment of the Emirate of Córdoba. After almost two centuries, the Emirate became the Caliphate of Córdoba in 929, until its dissolution a century later in 1031 into no less than 23 small kingdoms, called Taifa kingdoms.[65]

.jpg.webp)

The governors of the taifas each proclaimed themselves Emir of their provinces and established diplomatic relations with the Christian kingdoms of the north. Most of present-day Portugal fell into the hands of the Taifa of Badajoz of the Aftasid Dynasty, and after a short spell of an ephemeral Taifa of Lisbon in 1022, fell under the dominion of the Taifa of Seville of the Abbadids poets. The Taifa period ended with the conquest of the Almoravids who came from Morocco in 1086 winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Sagrajas, followed a century later in 1147, after the second period of Taifa, by the Almohads, also from Marrakesh.[66] Al-Andaluz was divided into different districts called Kura. Gharb Al-Andalus at its largest consisted of ten kuras,[67] each with a distinct capital and governor. The main cities of the period in Portugal were in the southern half of the country: Beja, Silves, Alcácer do Sal, Santarém and Lisbon. The Muslim population of the region consisted mainly of native Iberian converts to Islam (the so-called Muwallad or Muladi) and Arabs. The Arabs were principally noblemen from Syria and Yemen; and though few in numbers, they constituted the elite of the population. The Berbers were originally from the Rif and Atlas mountains region of North Africa and were nomads.[65]

County of Portugal

An Asturian Visigothic noble named Pelagius of Asturias was elected leader in 718[68] by many of the ousted Visigoth nobles. Pelagius called for the remnant of the Christian Visigothic armies to rebel against the Moors and regroup in the unconquered northern Asturian highlands, better known today as the Cantabrian Mountains, in what is today the small mountain region in north-western Spain, adjacent to the Bay of Biscay.[69]

Pelagius' plan was to use the Cantabrian mountains as a place of refuge and protection from the invading Moors. He then aimed to regroup the Iberian Peninsula's Christian armies and use the Cantabrian mountains as a springboard from which to regain their lands. In the process, after defeating the Moors in the Battle of Covadonga in 722, Pelagius was proclaimed king, thus founding the Christian Kingdom of Asturias and starting the war of Christian reconquest known in Portuguese as the Reconquista Cristã.[69]

At the end of the 9th century, the region of Portugal, between the rivers Minho and Douro, was reconquered from the Moors by the nobleman and knight Vímara Peres on the orders of King Alfonso III of Asturias. Finding that the region had previously had two major cities – Portus Cale in the coast and Braga in the interior, with many towns that were now deserted – he decided to repopulate and rebuild them with Portuguese and Galician refugees and other Christians.[70] Apart from the Arabs from the South, the coastal regions in the North were also attacked by Norman and Viking[71][72] raiders mainly from 844. The last great invasion, through the Minho (river), ended with the defeat of Olaf II Haraldsson in 1014 against the Galician nobility who also stopped further advances into the County of Portugal.

.png.webp)

Count Vímara Peres[73] organized the region he had reconquered, and elevated it to the status of County, naming it the County of Portugal after the region's major port city – Portus Cale or modern Porto. One of the first cities Vimara Peres founded at this time is Vimaranes, known today as Guimarães – the "birthplace of the Portuguese nation" or the "cradle city" (Cidade Berço in Portuguese).[70]

After annexing the County of Portugal into one of the several counties that made up the Kingdom of Asturias, King Alfonso III of Asturias knighted Vímara Peres, in 868, as the First Count of Portus Cale (Portugal). The region became known as Portucale, Portugale, and simultaneously Portugália – the County of Portugal.[70]

Later the Kingdom of Asturias was divided into a number of Christian Kingdoms in Northern Iberia due to dynastic divisions of inheritance among the king's offspring. With the forced abdication of Alfonso III "the Great" of Asturias by his sons in 910, the Kingdom of Asturias split into three separate kingdoms. The three kingdoms were eventually reunited in 924 under the crown of León.

In 1093, Alfonso VI of León bestowed the county to Henry of Burgundy and married him to his illegitimate daughter, Teresa of León, for his role in reconquering the land from Moors. Henry based his newly formed county in Bracara Augusta (modern Braga), capital city of the ancient Roman province, and also previous capital of several kingdoms over the first millennia.

Independence and Afonsine era

On 24 June 1128, the Battle of São Mamede occurred near Guimarães. Afonso Henriques, Count of Portugal, defeated his mother Countess Teresa and her lover Fernão Peres de Trava, thereby establishing himself as sole leader. Afonso then turned his arms against the Moors in the south.

Afonso's campaigns were successful and, on 25 July 1139, he obtained an overwhelming victory in the Battle of Ourique, and straight after was unanimously proclaimed King of Portugal by his soldiers. This is traditionally taken as the occasion when the County of Portugal, as a fief of the Kingdom of León, was transformed into the independent Kingdom of Portugal.

Afonso then established the first of the Portuguese Cortes at Lamego, where he was crowned by the Archbishop of Braga, though the validity of the Cortes of Lamego has been disputed and called a myth created during the Portuguese Restoration War. Afonso was recognized in 1143 by King Alfonso VII of León, and in 1179 by Pope Alexander III.

During the Reconquista period, Christians reconquered the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish domination. Afonso Henriques and his successors, aided by military monastic orders, pushed southward to drive out the Moors. At this time, Portugal covered about half of its present area. In 1249, the Reconquista ended with the capture of the Algarve and complete expulsion of the last Moorish settlements on the southern coast, giving Portugal its present-day borders, with minor exceptions.

In one of these situations of conflict with the kingdom of Castile, Dinis I of Portugal signed with the king Fernando IV of Castile (who was represented, when a minor, by his mother the queen Maria de Molina) the Treaty of Alcañices (1297), which stipulated that Portugal abolished agreed treaties against the kingdom of Castile for supporting the infant Juan de Castilla. This treaty established among other things the border demarcation between the kingdom of Portugal and the kingdom of Leon, where the disputed town of Olivenza was included.

The reigns of Dinis I (Denis I), Afonso IV (Alphons IV), and Pedro I (Peter I) for the most part saw peace with the Christian kingdoms of Iberia.

In 1348 and 1349 Portugal, like the rest of Europe, was devastated by the Black Death.[74] In 1373, Portugal made an alliance with England, which is one of the oldest standing alliances in the world. Over time, this went far beyond geo-political and military cooperation (protecting both nations' interests in Africa, the Americas and Asia against French, Spanish and Dutch rivals) and maintained strong trade and cultural ties between the two old European allies. In the Oporto region, in particular, there is visible English influence to this day.

Joanine era and Age of Discoveries

In 1383, John I of Castile, husband of Beatrice of Portugal and son-in-law of Ferdinand I of Portugal, claimed the throne of Portugal. A faction of petty noblemen and commoners, led by John of Aviz (later King John I of Portugal) and commanded by General Nuno Álvares Pereira defeated the Castilians in the Battle of Aljubarrota. With this battle, the House of Aviz became the ruling house of Portugal.

The new ruling dynasty would proceed to push Portugal to the limelight of European politics and culture, creating and sponsoring works of literature, like the Crónicas d'el Rei D. João I by Fernão Lopes, the first riding and hunting manual Livro da ensinança de bem cavalgar toda sela and O Leal Conselheiro both by King Edward of Portugal[75][76][77] and the Portuguese translations of Cicero's De Oficiis and Seneca's De Beneficiis by the well traveled Prince Peter of Coimbra, as well as his magnum opus Tratado da Vertuosa Benfeytoria.[78] In an effort of solidification and centralization of royal power the monarchs of this dynasty also ordered the compilation, organization and publication of the first three compilations of laws in Portugal: the Ordenações d'el Rei D. Duarte,[79] which was never enforced; the Ordenações Afonsinas, whose application and enforcement was not uniform across the realm; and the Ordenações Manuelinas, which took advantage of the printing press to reach every corner of the kingdom. The Avis Dynasty also sponsored works of architecture like the Mosteiro da Batalha (literally, the Monastery of the Battle) and led to the creation of the manueline style of architecture in the 16th century.

Portugal also spearheaded European exploration of the world and the Age of Discovery. Prince Henry the Navigator, son of King John I of Portugal, became the main sponsor and patron of this endeavour. During this period, Portugal explored the Atlantic Ocean, discovering the Atlantic archipelagos the Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde; explored the African coast; colonized selected areas of Africa; discovered an eastern route to India via the Cape of Good Hope; discovered Brazil, explored the Indian Ocean, established trading routes throughout most of southern Asia; and sent the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to China and Japan.

In 1415, Portugal acquired the first of its overseas colonies by conquering Ceuta, the first prosperous Islamic trade centre in North Africa. There followed the first discoveries in the Atlantic: Madeira and the Azores, which led to the first colonization movements.

In 1422, by decree of King John I, Portugal officially abandoned the previous dating system, the Era of Caesar, and adopted the Anno Domini system, therefore becoming the last catholic realm to do so.[80]

Throughout the 15th century, Portuguese explorers sailed the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts for several common types of tradable commodities at the time, ranging from gold to slaves, as they looked for a route to India and its spices, which were coveted in Europe.

The Treaty of Tordesillas, intended to resolve the dispute that had been created following the return of Christopher Columbus, was made by Pope Alexander VI, the mediator between Portugal and Spain. It was signed on 7 June 1494, and divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the two countries along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (off the west coast of Africa).

In 1498, Vasco da Gama accomplished what Columbus set out to do and became the first European to reach India by sea, bringing economic prosperity to Portugal and its population of 1.7 million residents, and helping to start the Portuguese Renaissance. In 1500, the Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real reached what is now Canada and founded the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip's, Newfoundland and Labrador, long before the French and English in the 17th century, and being just one of many Portuguese colonizations of the Americas.[81][82][83]

In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil and claimed it for Portugal.[84] Ten years later, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa in India, Muscat and Ormuz in the Persian Strait, and Malacca, now a state in Malaysia. Thus, the Portuguese empire held dominion over commerce in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic. Portuguese sailors set out to reach Eastern Asia by sailing eastward from Europe, landing in such places as Taiwan, Japan, the island of Timor, and in the Moluccas.

Although for a long period it was believed the Dutch were the first Europeans to arrive in Australia, there is also some evidence that the Portuguese may have discovered Australia in 1521.[85][86][87] From 1519 to 1522, Ferdinand Magellan (Fernão de Magalhães) organized a Spanish expedition to the East Indies which resulted in the first circumnavigation of the globe. Magellan never made it back to Europe as he was killed by natives in the Philippines in 1521.

The Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529 between Portugal and Spain, specified the anti-meridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas.

All these factors made Portugal one of the world's major economic, military, and political powers from the 15th century until the late 16th century.

Iberian Union, Restoration and early Brigantine era

Portugal voluntarily entered a dynastic union between 1580 and 1640. This occurred because the last two kings of the House of Aviz – King Sebastian, who died in the battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco, and his great-uncle and successor, King-Cardinal Henry of Portugal – both died without heirs, resulting in the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Subsequently, Philip II of Spain claimed the throne and was accepted as Philip I of Portugal. Portugal did not lose its formal independence, briefly forming a union of kingdoms. At this time Spain was a geographic territory.[88] The joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of an independent foreign policy and led to its involvement in the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands.

War led to a deterioration of the relations with Portugal's oldest ally, England, and the loss of Hormuz, a strategic trading post located between Iran and Oman. From 1595 to 1663 the Dutch-Portuguese War primarily involved the Dutch companies invading many Portuguese colonies and commercial interests in Brazil, Africa, India and the Far East, resulting in the loss of the Portuguese Indian sea trade monopoly. In 1640, John IV of Portugal spearheaded an uprising backed by disgruntled nobles and was proclaimed king. The Portuguese Restoration War ended the sixty-year period of the Iberian Union under the House of Habsburg. This was the beginning of the House of Braganza, which reigned in Portugal until 1910.

King John IV's eldest son came to reign as Afonso VI, however his physical and mental disabilities left him overpowered by Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa, 3rd Count of Castelo Melhor. In a palace coup organized by the King's wife, Maria Francisca of Savoy, and his brother, Pedro, Duke of Beja, King Afonso VI was declared mentally incompetent and exiled first to the Azores and then to the Royal Palace of Sintra, outside Lisbon. After Afonso's death, Pedro came to the throne as King Pedro II. Pedro's reign saw the consolidation of national independence, imperial expansion, and investment in domestic production.

Pedro II's son, John V, saw a reign characterized by the influx of gold into the coffers of the royal treasury, supplied largely by the royal fifth (a tax on precious metals) that was received from the Portuguese colonies of Brazil and Maranhão.

Disregarding traditional Portuguese institutions of governance, John V acted as an absolute monarch, nearly depleting the country's tax revenues on ambitious architectural works, most notably Mafra Palace, and on commissions and additions for his sizeable art and literary collections.

Owing to his craving for international diplomatic recognition, John also spent large sums on the embassies he sent to the courts of Europe, the most famous being those he sent to Paris in 1715 and Rome in 1716.

Official estimates – and most estimates made so far – place the number of Portuguese migrants to Colonial Brazil during the gold rush of the 18th century at 600,000.[89] This represented one of the largest movements of European populations to their colonies in the Americas during colonial times.

Pombaline era and Enlightenment

In 1738, fidalgo Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (later ennobled as the 1st Marquis of Pombal) began a diplomatic career as the Portuguese Ambassador in London and later in Vienna. The Queen consort of Portugal, Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria, was fond of Carvalho e Melo; and after his first wife died, she arranged the widowed Carvalho e Melo's second marriage to the daughter of the Austrian field marshal Leopold Josef, Count von Daun. King John V, however, was not pleased and recalled Carvalho e Melo to Portugal in 1749. John V died the following year and his son, Joseph I, was crowned. In contrast to his father, Joseph I was fond of Carvalho e Melo, and with the Queen Mother's approval, he appointed Carvalho e Melo as Minister of Foreign Affairs.

As the King's confidence in Carvalho e Melo increased, the King entrusted him with more control of the state. By 1755, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo was made Prime Minister. Impressed by British economic success that he had witnessed from his time as an Ambassador, he successfully implemented similar economic policies in Portugal. He abolished slavery in mainland Portugal and in the Portuguese colonies in India, reorganized the army and the navy, restructured the University of Coimbra, and ended legal discrimination against different Christian sects in Portugal by abolishing the distinction between Old and New Christians.

Carvalho e Melo's greatest reforms were economic and financial, with the creation of several companies and guilds to regulate every commercial activity. He created one of the first appellation systems in the world by demarcating the region for production of Port to ensure the wine's quality; and this was the first attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe. He ruled with a strong hand by imposing strict law upon all classes of Portuguese society from the high nobility to the poorest working class, along with a widespread review of the country's tax system. These reforms gained him enemies in the upper classes, especially among the high nobility, who despised him as a social upstart.

Disaster fell upon Portugal in the morning of 1 November 1755, when Lisbon was struck by a violent earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 8.5–9. The city was razed to the ground by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami and ensuing fires.[90] Carvalho e Melo survived by a stroke of luck and then immediately embarked on rebuilding the city, with his famous quote: "What now? We bury the dead and take care of the living."

Despite the calamity and huge death toll, Lisbon suffered no epidemics and within less than one year was already being rebuilt. The new city centre of Lisbon was designed to resist subsequent earthquakes. Architectural models were built for tests, and the effects of an earthquake were simulated by having troops march around the models. The buildings and large squares of the Pombaline Downtown still remain as one of Lisbon's tourist attractions. Carvalho e Melo also made an important contribution to the study of seismology by designing a detailed inquiry on the effects of the earthquake, the Parochial Memories of 1758, that was sent to every parish in the country; this wealth of information allows modern scientists to reconstruct the event with some degree of scientific precision while also giving current historians an immense amount of demographic, topographic and prosopographic information on the rest of the kingdom as well as information on its urban and rural areas.

Following the earthquake, Joseph I gave his Prime Minister even more power, and Carvalho de Melo became a powerful, progressive dictator. As his power grew, his enemies increased in number, and bitter disputes with the upper nobility became frequent. In 1758 Joseph I was wounded in an attempted assassination. The Távora family and the Duke of Aveiro were implicated and summarily executed after a quick trial. The following year, the Jesuits were suppressed and expelled from the country and their assets confiscated by the crown. Carvalho e Melo spared none involved, even women and children (notably, eight-year-old Leonor de Almeida Portugal, imprisoned in a convent for nineteen years). This was the final stroke that crushed all opposition by publicly demonstrating even the aristocracy was powerless before the King's loyal minister. Joseph I ennobled Carvalho e Melo as Count of Oeiras in 1759.

In 1762, Spain invaded Portuguese territory as part of the Seven Years' War, but by 1763 the status quo between Spain and Portugal before the war had been restored.

Following the Távora affair, the new Count of Oeiras knew no opposition. Further titled "Marquês de Pombal" in 1770, he effectively ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1777.

The new ruler, Queen Maria I of Portugal, disliked the Marquês de Pombal because of the power he amassed, and never forgave him for the ruthlessness with which he dispatched the Távora family, and upon her accession to the throne, she withdrew all his political offices. The Marquês de Pombal was banished to his estate at Pombal, where he died in 1782.

However, historians also argue that Pombal's "enlightenment," while far-reaching, was primarily a mechanism for enhancing autocracy at the expense of individual liberty and especially an apparatus for crushing opposition, suppressing criticism, and furthering colonial economic exploitation as well as intensifying book censorship and consolidating personal control and profit.[91]

Napoleonic era

With the invasions by Napoleon, Portugal began a slow but inexorable decline that lasted until the 20th century. This decline was hastened by the independence of Brazil, the country's largest colonial possession.

In the autumn of 1807, Napoleon moved French troops through Spain to invade Portugal. From 1807 to 1811, British-Portuguese forces successfully fought against the French invasion of Portugal in the Peninsular War, during which the royal family and the Portuguese nobility, including Maria I, relocated to the Portuguese territory of Brazil, at that time a colony of the Portuguese Empire, in South America. This episode is known as the Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil.

In 1807, as Napoleon's army closed in on Lisbon, João VI of Portugal, the prince regent, transferred his court to Brazil and established Rio de Janeiro as the capital of the Portuguese Empire. In 1815, Brazil was declared a Kingdom and the Kingdom of Portugal was united with it, forming a pluricontinental state, the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

As a result of the change in its status and the arrival of the Portuguese royal family, Brazilian administrative, civic, economical, military, educational, and scientific apparatus were expanded and highly modernized. Portuguese and their allied British troops fought against the French Invasion of Portugal and by 1815 the situation in Europe had cooled down sufficiently that João VI would have been able to return safely to Lisbon. However, the King of Portugal remained in Brazil until the Liberal Revolution of 1820, which started in Porto, demanded his return to Lisbon in 1821.

Thus he returned to Portugal but left his son Pedro in charge of Brazil. When the Portuguese Government attempted the following year to return the Kingdom of Brazil to subordinate status, his son Pedro, with the overwhelming support of the Brazilian elites, declared Brazil's independence from Portugal. Cisplatina (today's sovereign state of Uruguay), in the south, was one of the last additions to the territory of Brazil under Portuguese rule.

Brazilian independence was recognized in 1825, whereby Emperor Pedro I granted to his father the titular honour of Emperor of Brazil. John VI's death in 1826 caused serious questions in his succession. Though Pedro was his heir, and reigned briefly as Pedro IV, his status as a Brazilian monarch was seen as an impediment to holding the Portuguese throne by both nations. Pedro abdicated in favour of his daughter, Maria II (Mary II). However, Pedro's brother, Infante Miguel, claimed the throne in protest. After a proposal for Miguel and Maria to marry failed, Miguel seized power as King Miguel I, in 1828. In order to defend his daughter's rights to the throne, Pedro launched the Liberal Wars to reinstall his daughter and establish a constitutional monarchy in Portugal. The war ended in 1834, with Miguel's defeat, the promulgation of a constitution, and the reinstatement of Queen Maria II.

Constitutional monarchy

.jpg.webp)

Queen Maria II (Mary II) and King Ferdinand II's son, King Pedro V (Peter V) modernized the country during his short reign (1853–1861). Under his reign, roads, telegraphs, and railways were constructed and improvements in public health advanced. His popularity increased when, during the cholera outbreak of 1853–1856, he visited hospitals handing out gifts and comforting the sick. Pedro's reign was short, as he died of cholera in 1861, after a series of deaths in the royal family, including his two brothers Infante Fernando and Infante João, Duke of Beja, and his wife, Stephanie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Pedro not having children, his brother, Luís I of Portugal (Louis I) ascended the throne and continued his modernization.

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had already lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. Luanda, Benguela, Bissau, Lourenço Marques, Porto Amboim and the Island of Mozambique were among the oldest Portuguese-founded port cities in its African territories. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there.

With the Conference of Berlin of 1884, Portuguese territories in Africa had their borders formally established on request of Portugal in order to protect the centuries-long Portuguese interests in the continent from rivalries enticed by the Scramble for Africa. Portuguese towns and cities in Africa like Nova Lisboa, Sá da Bandeira, Silva Porto, Malanje, Tete, Vila Junqueiro, Vila Pery and Vila Cabral were founded or redeveloped inland during this period and beyond. New coastal towns like Beira, Moçâmedes, Lobito, João Belo, Nacala and Porto Amélia were also founded. Even before the turn of the 20th century, railway tracks as the Benguela railway in Angola, and the Beira railway in Mozambique, started to be built to link coastal areas and selected inland regions.

Other episodes during this period of the Portuguese presence in Africa include the 1890 British Ultimatum. This forced the Portuguese military to retreat from the land between the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola (most of present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia), which had been claimed by Portugal and included in its "Pink Map", which clashed with British aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway.

The Portuguese territories in Africa were Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Portuguese Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique. The tiny fortress of São João Baptista de Ajudá on the coast of Dahomey, was also under Portuguese rule. In addition, Portugal still ruled the Asian territories of Portuguese India, Portuguese Timor and Portuguese Macau.

On 1 February 1908, King Dom Carlos I of Portugal and his heir apparent and his eldest son, Prince Royal Dom Luís Filipe, Duke of Braganza, were assassinated in Lisbon in the Terreiro do Paço by two Portuguese republican activist revolutionaries, Alfredo Luís da Costa and Manuel Buíça. Under his rule, Portugal had been declared bankrupt twice – first on 14 June 1892, and then again on 10 May 1902 – causing social turmoil, economic disturbances, angry protests, revolts and criticism of the monarchy. His second and youngest son, Manuel II of Portugal, became the new king, but was eventually overthrown by the 5 October 1910 Portuguese republican revolution, which abolished the monarchy and installed a republican government in Portugal, causing him and his royal family to flee into exile in London, England.

First Republic and Estado Novo

The new republic had many problems. Portugal had 45 different governments in just 15 years. During World War 1 (1914–1918), Portugal helped the Allies fight the Central Powers, however the war hurt its weak economy. Political instability and economic weaknesses were fertile ground for chaos and unrest during the First Portuguese Republic. These conditions would lead to the failed Monarchy of the North, 28 May 1926 coup d'état, and the creation of the National Dictatorship (Ditadura Nacional). This in turn led to the establishment of the right-wing dictatorship of the Estado Novo under António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933.

Portugal remained neutral in World War II. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Portugal was a founding member of NATO, OECD and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Gradually, new economic development projects and relocation of mainland Portuguese citizens into the overseas provinces in Africa were initiated, with Angola and Mozambique, as the largest and richest overseas territories, being the main targets of those initiatives. These actions were used to affirm Portugal's status as a transcontinental nation and not as a colonial empire.

_%E2%80%93_Google_Art_Project.png.webp)

After India attained independence in 1947, pro-Indian residents of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, with the support of the Indian government and the help of pro-independence organizations, separated the territories of Dadra and Nagar Haveli from Portuguese rule in 1954.[92] In 1961, Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá's annexation by the Republic of Dahomey was the start of a process that led to the final dissolution of the centuries-old Portuguese Empire.

According to the census of 1921 São João Baptista de Ajudá had five inhabitants and, at the moment of the ultimatum by the Dahomey Government, it had only two inhabitants representing Portuguese Sovereignty.

Another forcible retreat from overseas territories occurred in December 1961 when Portugal refused to relinquish the territories of Goa, Daman and Diu in India. As a result, the Portuguese army and navy were involved in armed conflict in its colony of Portuguese India against the Indian Armed Forces.

The operations resulted in the defeat and surrender of the limited Portuguese defensive garrison, which was forced to surrender to a much larger military force. The outcome was the loss of the remaining Portuguese territories in the Indian subcontinent. The Portuguese regime refused to recognize Indian sovereignty over the annexed territories, which continued to be represented in Portugal's National Assembly until the military coup of 1974.

Also in the early 1960s, independence movements in the Portuguese overseas provinces of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea in Africa, resulted in the Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974).

The war lasted thirteen years, mobilized around 1.4 million men for military or for civilian support service,[93] and led to big casualties from military to civilians, plus evacuations of thousands from war zones.

Throughout the colonial war period Portugal had to deal with increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions imposed by most of the international community.

However, the authoritarian and conservative Estado Novo regime, first installed and governed by António de Oliveira Salazar and from 1968 onwards led by Marcelo Caetano, tried to preserve a vast centuries-long intercontinental empire with a total area of 2,168,071 km2 (837,097 sq mi).[94]

Carnation Revolution and European integration

The Portuguese government and army resisted the decolonization of its overseas territories until April 1974, when a left-wing military coup in Lisbon, known as the Carnation Revolution, led the way for the independence of the overseas territories in Africa and Asia, as well as for the restoration of democracy after two years of a transitional period known as PREC (Processo Revolucionário Em Curso). This period was characterized by social turmoil and power disputes between left- and right-wing political forces. By the summer of 1975, the tension between these was so high, that the country was on the verge of civil war. The forces connected to the extreme left-wing launched a further coup d'état on 25 November but the Group of Nine, a moderate military faction, immediately initiated a counter-coup. The main episode of this confrontation was the successful assault on the barracks of the left-wing dominated Military Police Regiment by the moderate forces of the Commando Regiment, resulting in three soldiers killed in action.

.jpg.webp)

The Group of Nine emerged victorious, thus preventing the establishment of a communist state in Portugal and ending the period of political instability in the country. The retreat from the overseas territories and the acceptance of its independence terms by Portuguese head representatives for overseas negotiations, which would create independent states in 1975, prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens from Portugal's African territories (mostly from Portuguese Angola and Mozambique).[95][96]

Over one million Portuguese refugees fled the former Portuguese provinces as white settlers were usually not considered part of the new identities of the former Portuguese colonies in Africa and Asia. Mário Soares and António de Almeida Santos were charged with organizing the independence of Portugal's overseas territories. By 1975, all the Portuguese African territories were independent and Portugal held its first democratic elections in 50 years.

Portugal continued to be governed by a Junta de Salvação Nacional until the Portuguese legislative election of 1976. It was won by the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) and Mário Soares, its leader, became Prime Minister of the 1st Constitutional Government on 23 July. Mário Soares would be Prime Minister from 1976 to 1978 and again from 1983 to 1985. In this capacity Soares tried to resume the economic growth and development record that had been achieved before the Carnation Revolution, during the last decade of the previous regime. He initiated the process of accession to the European Economic Community (EEC) by starting accession negotiations as early as 1977.

_op_Schiphol_aangeko%252C_Bestanddeelnr_927-7110.jpg.webp)

After the transition to democracy, Portugal bounced between socialism and adherence to the neoliberal model. Land reform and nationalizations were enforced; the Portuguese Constitution (approved in 1976) was rewritten in order to accommodate socialist and communist principles. Until the constitutional revisions of 1982 and 1989, the constitution was a document with numerous references to socialism, the rights of workers, and the desirability of a socialist economy. Portugal's economic situation after the revolution obliged the government to pursue International Monetary Fund (IMF)-monitored stabilization programmes in 1977–78 and 1983–85.

In 1986, Portugal, along with Spain, joined the European Economic Community (EEC) that later became the European Union (EU). In the following years Portugal's economy progressed considerably as a result of EEC/EU structural and cohesion funds and Portuguese companies' easier access to foreign markets.

Portugal's last overseas and Asian colonial territory, Macau, was peacefully handed over to the People's Republic of China (PRC) on 20 December 1999, under the 1987 joint declaration that set the terms for Macau's handover from Portugal to the PRC. In 2002, the independence of East Timor (Asia) was formally recognized by Portugal, after an incomplete decolonization process that was started in 1975 because of the Carnation Revolution, but interrupted by an Indonesian armed invasion and occupation.

.jpg.webp)

On 26 March 1995, Portugal started to implement Schengen Area rules, eliminating border controls with other Schengen members while simultaneously strengthening border controls with non-member states. In 1996 the country was a co-founder of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) headquartered in Lisbon. In 1996, Jorge Sampaio became president. He won re-election in January 2001. Expo '98 took place in Portugal and in 1999 it was one of the founding countries of the euro and the eurozone. On 5 July 2004, José Manuel Barroso, then Prime Minister of Portugal, was nominated President of the European Commission, the most powerful office in the European Union. On 1 December 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force, after it had been signed by the European Union member states on 13 December 2007 in the Jerónimos Monastery, in Lisbon, enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and improving the coherence of its action. Ireland was the only EU state to hold a democratic referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. It was initially rejected by voters in 2008.

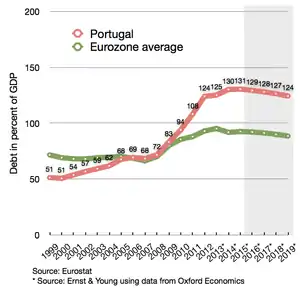

Economic disruption and an unsustainable growth in government debt during the financial crisis of 2007–2008 led the country to negotiate in 2011 with the IMF and the European Union, through the European Financial Stability Mechanism (EFSM) and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), a loan to help the country stabilize its finances.

Geography

Portugal occupies an area on the Iberian Peninsula (referred to as the continent by most Portuguese) and two archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean: Madeira and the Azores. It lies between latitudes 30° and 42° N, and longitudes 32° and 6° W.

Mainland Portugal is split by its main river, the Tagus, that flows from Spain and disgorges in the Tagus Estuary at Lisbon, before escaping into the Atlantic. The northern landscape is mountainous towards the interior with several plateaus indented by river valleys, whereas the south, including the Algarve and the Alentejo regions, is characterized by rolling plains.[97]

Portugal's highest peak is the similarly named Mount Pico on the island of Pico in the Azores. This ancient volcano, with a height of 2,351 m (7,713 ft) is an iconic symbol of the Azores. Serra da Estrela on the mainland (the summit being 1,991 m (6,532 ft) above sea level) is an important seasonal attraction for skiers and winter sports enthusiasts.

The archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores are scattered within the Atlantic Ocean: the Azores straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge on a tectonic triple junction, and Madeira along a range formed by in-plate hotspot geology. Geologically, these islands were formed by volcanic and seismic events. The last terrestrial volcanic eruption occurred in 1957–58 (Capelinhos) and minor earthquakes occur sporadically, usually of low intensity.

The exclusive economic zone, a sea zone over which the Portuguese have special rights in exploration and use of marine resources, covers an area of 1,727,408 km2 (666,956 sq mi). This is the 3rd largest exclusive economic zone of the European Union and the 20th largest in the world.[98]

Climate

Portugal is mainly characterized by a Mediterranean climate (Csa in the South, central interior, and the Douro river valley; Csb in the North, Central west and Vicentine Coast),[99] temperate maritime climate (Cfb) in the mainland north-western highlands and mountains, and in some high altitude zones of the Azorean islands; a semi-arid climate in certain parts of the Beja District far south (BSk) and in Porto Santo Island (BSh), a warm desert climate (BWh) in the Selvagens Islands and a humid subtropical climate in the western Azores (Cfa), according to the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification. It is one of the warmest countries in Europe: the annual average temperature in mainland Portugal varies from 10–12 °C (50.0–53.6 °F) in the mountainous interior north to 16–18 °C (60.8–64.4 °F) in the south and on the Guadiana river basin. There are however, variations from the highlands to the lowlands: Spanish biologist Salvador Rivas Martinez presents several different bioclimatic zones for Portugal.[100] The Algarve, separated from the Alentejo region by mountains reaching up to 900 metres (3,000 ft) in Alto da Fóia, has a climate similar to that of the southern coastal areas of Spain or Southwest Australia.

Annual average rainfall in the mainland varies from just over 3,200 mm (126.0 in) on the Peneda-Gerês National Park to less than 500 mm (19.7 in) in southern parts of Alentejo. Mount Pico is recognized as receiving the largest annual rainfall (over 6,250 mm (246.1 in) per year) in Portugal, according to Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera.

In some areas, such as the Guadiana basin, annual diurnal average temperatures can be as high as 24 °C (75 °F), and summer's highest temperatures are routinely over 40 °C (104 °F). The record high of 47.4 °C (117.3 °F) was recorded in Amareleja, although this might not be the hottest spot in summer, according to satellite readings.[101][102]

%252C_by_Klugschnacker_in_Wikipedia_(86).JPG.webp)

Snowfalls occur regularly in the winter in the interior North and Centre of the country in districts such as Guarda, Bragança, Viseu and Vila Real, particularly on the mountains. In winter, temperatures may drop below −10.0 °C (14.0 °F), particularly in Serra da Estrela, Serra do Gerês, Serra do Marão and Serra de Montesinho. In these places snow can fall any time from October to May. In the South of the country snowfalls are rare but still occur in the highest elevations. While the official absolute minimum by IPMA is −16.0 °C (3.2 °F) in Penhas da Saúde and Miranda do Douro, lower temperatures have been recorded, such as −17.5 °C (0.5 °F) by Bragança Polytechnic Institute in the outskirts of the city in 1983, and below −20.0 °C (−4.0 °F) in Serra da Estrela.

Continental Portugal receives around 2,300 to 3,200 hours of sunshine a year, an average of 4–6 hours in winter and 10–12 hours in the summer, with higher values in the south-east, south-west and the Algarve coast and lower in the north-west. Insolation values are lower in the archipelagos, with around 1,600 hours in the humid Flores Island and around 2,300 hours in the island of Madeira and Porto Santo. Insolation in the Selvagens is thought to be higher due to weaker orographic lift and their relative proximity to the Sahara Desert.

Portugal's central west and southwest coasts have an extreme ocean seasonal lag, sea temperatures are warmer in October than in July and are their coldest in March. The average sea surface temperature on the west coast of mainland Portugal varies from 14–16 °C (57.2–60.8 °F) in January−March to 19–21 °C (66.2–69.8 °F) in August−October while on the south coast it ranges from 16 °C (60.8 °F) in January−March and rises in the summer to about 22–23 °C (71.6–73.4 °F), occasionally reaching 26 °C (78.8 °F).[103] In the Azores, around 16 °C (60.8 °F) in February−April to 22–24 °C (71.6–75.2 °F) in July−September,[104] and in Madeira, around 18 °C (64.4 °F) in February−April to 23–24 °C (73.4–75.2 °F) in August−October.[105]

Both the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira have a subtropical climate, although variations between islands exist, making weather predictions very difficult (owing to rough topography). The Madeira and Azorean archipelagos have a narrower temperature range, with annual average temperatures exceeding 20 °C (68 °F) in some parts of the coast (according to the Portuguese Meteorological Institute). Some islands in Azores do have drier months in the summer. Consequently, the islands of the Azores have been identified as having a Mediterranean climate (both Csa and Csb types), while some islands (such as Flores or Corvo) are classified as Humid subtropical (Cfa), transitioning into an Oceanic climate (Cfb) at higher altitudes, according to Köppen-Geiger classification.

Porto Santo Island in Madeira has a warm semi-arid climate (BSh). The Savage Islands, which are part of the regional territory of Madeira and a nature reserve are unique in being classified as a desert climate (BWh) with an annual average rainfall of approximately 150 mm (5.9 in). The sea surface temperature in these islands varies from 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) in winter to 23–24 °C (73.4–75.2 °F) in the summer occasionally reaching 25 °C (77.0 °F).

Biodiversity

.jpg.webp)

Portugal is located on the Mediterranean Basin, the third most diverse hotspot of flora in the world.[106] Due to its geographical and climatic context - between the Atlantic and Mediterranean - Portugal has a high level of biodiversity on land and at sea. It is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Azores temperate mixed forests, Cantabrian mixed forests, Madeira evergreen forests, Iberian sclerophyllous and semi-deciduous forests, Northwest Iberian montane forests, and Southwest Iberian Mediterranean sclerophyllous and mixed forests.[107] Over 22% of its land area is included in the Natura 2000 network, including 62 special conservation areas and 88 types of protected landscape natural habitats.[108][106]

Eucalyptus (non-native, commercial plantations), cork oak and maritime pine together make up 71% of the total forested area of continental Portugal, followed by the holm oak, the stone pine, the other oak trees (Q. robur, Q. faginea and Q. pyrenaica) and the sweet chestnut, respectively.[109] In Madeira, laurisilva (recognized as a World Heritage Site) dominates the landscape, especially on the northern slope. The predominant species in this forest include Laurus novocanariensis, Apollonias barbujana, Ocotea foetens and Persea indica. Before human occupation the Azores were also rich in dense laurisilva forests, today these native forests are undermined by the introduced Pittosporum undulatum and Cryptomeria japonica.[110][111] There have been several projects aimed to recover the Laurisilva present in the Azores.[112] Remnants of these laurisilva forests are also present in continental Portugal with its few living testimonies Laurus nobilis, Prunus lusitanica, Arbutus unedo, Myrica faya and Rhododendron ponticum.[113]

These geographical and climatic conditions facilitate the introduction of exotic species that later turn to be invasive and destructive to the native habitats. Around 20% of the total number of extant species in continental Portugal are exotic.[114] In Madeira, around 36%[115] and in the Azores, around 70% species are exotic.[116][117] Due to this, Portugal was placed 168th globally out of 172 countries on the Forest Landscape Integrity Index in 2019.[118]

Portugal is the second country in Europe with the highest number of threatened animal and plant species (488 as of 2020).[119][120]

Portugal as a whole is an important stopover for migratory bird species: the southern marshes of the eastern Algarve (Ria Formosa, Castro Marim) and the Lisbon Region (Tagus Estuary, Sado Estuary) hosting various aquatic bird species, the Bonelli's eagle and Egyptian vulture on the northern valleys of the Douro International, the black stork and griffon vulture on the Tagus International, the seabird sanctuaries of the Savage Islands and Berlengas and the highlands of Madeira and São Miguel all represent the great diversity of wild avian species (around 450 in continental Portugal), not only migratory but also endemic (e.g. trocaz pigeon, Azores bullfinch) or exotic (crested myna, pin-tailed whydah).[121][122]

The large mammalian species of Portugal (the fallow deer, red deer, roe deer, Iberian ibex, wild boar, red fox, Iberian wolf and Iberian lynx) were once widespread throughout the country, but intense hunting, habitat degradation and growing pressure from agriculture and livestock reduced population numbers on a large scale in the 19th and early 20th century, others, such as the Portuguese ibex were even led to extinction. Today, these animals are re-expanding their native range.[123][124] Smaller mammals include the red squirrel, European badger, Eurasian otter, Egyptian mongoose, Granada hare, European rabbit, common genet, European wildcat, among others.[124]

Due to their isolated location, the volcanic islands of the Azores, Madeira and Salvages, part of Macaronesia, have many endemic species that have evolved independently from their European, African and occasionally American relatives.

The Portuguese west coast is part of the four major Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems of the ocean. This seasonal upwelling system typically seen during the summer months brings cooler, nutrient rich water up to the sea surface promoting phytoplankton growth, zooplankton development and the subsequent rich diversity in pelagic fish and other marine invertebrates.[125]

This, adding to its large EEZ makes Portugal one of the largest per capita fish-consumers in the world.[126] Sardines (Sardina pilchardus) and horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) are collected in the thousands every year.[127] while blue whiting, monkfish, Atlantic cod, cephalopods, skates or any other form of seafood are traditionally fished in the local coastal villages.[128] This upwelling also allows Portugal to have kelp forests which are otherwise very uncommon or non-existent on the Mediterranean.[129]

73% of the freshwater fish occurring in the Iberian Peninsula are endemic, the largest out of any region in Europe.[130] Many of these endemic species are concentrated in bodies of water of the central western region (one exclusively endemic), these and other bodies of water throughout the Peninsula are mostly temporary and prone to drought every year, placing most of these species under Threatened status.[131]

Around 24[132] to 28[133] species of cetacean roam through the Azores, making it one of four places in the world where most species of this infraorder occur.[132] Starting in the mid-19th century and ceasing in 1984, whaling (especially of sperm whale) heavily exploited this diversity. Beginning in the early 90s, whale watching quickly grew to popularity and is now one of the main economic activities in the Portuguese archipelago.[134][135]

Some protected areas in Portugal other than the ones previously mentioned include: the Serras de Aire e Candeeiros with its limestone formations, paleontological history and great diversity in bats and orchids,[136] the Southwest Alentejo and Vicentine Coast Natural Park with its well preserved, wild coastline.[137] the Montesinho Natural Park which hosts some of the only populations of Iberian wolf and recent sightings of Iberian brown bear,[138] which had been considered extinct in the country; among other species.

Government and politics

Portugal has been a semi-presidential representative democratic republic since the ratification of the Constitution of 1976, with Lisbon, the nation's largest city, as its capital.[139] The Constitution grants the division or separation of powers among four "sovereignty bodies": the President of the Republic, the Government, the Assembly of the Republic and the Courts.[140]

The President, who is elected to a five-year term, has an executive role: the current President is Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. The Assembly of the Republic is a single chamber parliament composed of a maximum of 230 deputies elected for a four-year term. The Government is headed by the Prime Minister (currently António Costa) and includes Ministers and Secretaries of State. The Courts are organized into several levels, among the judicial, administrative and fiscal branches. The Supreme Courts are institutions of last resort/appeal. A thirteen-member Constitutional Court oversees the constitutionality of the laws.

Portugal operates a multi-party system of competitive legislatures/local administrative governments at the national, regional and local levels. The Assembly of the Republic, Regional Assemblies and local municipalities and parishes, are dominated by two political parties, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party, in addition to Enough, the Liberal Initiative, the Unitary Democratic Coalition (Portuguese Communist Party and Ecologist Party "The Greens") and the Left Bloc, which garner between 5 and 15% of the vote regularly.

Presidency of the Republic

The Head of State of Portugal is the President of the Republic, elected to a five-year term by direct, universal suffrage. Presidential powers include the appointment of the Prime Minister and the other members of the Government (where the President takes into account the results of legislative elections); dismissing the Prime Minister; dissolving the Assembly of the Republic (to call early elections); vetoing legislation (which may be overridden by the Assembly); and declaring a state of war or siege. The President has also supervisory and reserve powers and is the ex officio Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

The President is advised on issues of importance by the Council of State, which is composed of six senior civilian officers, any former Presidents elected under the 1976 Constitution, five members chosen by the Assembly, and five selected by the president.

Government

The Government is headed by the presidentially appointed Prime Minister, also including one or more Deputy Prime Ministers, Ministers, Secretaries of State and Under-Secretaries of State.

The Government is both the organ of sovereignty that conducts the general politics of the country and the superior body of the public administration.

It has essentially Executive powers, but has also limited legislative powers. The Government can legislate about its own organization, about areas covered by legislative authorizations conceded by the Assembly of the Republic and about the specific regulation of generalist laws issued by the Assembly.

The Council of Ministers – under the presidency of the Prime Minister (or the President of Portugal at the latter's request) and the Ministers (may also include one or more Deputy Prime Ministers) – acts as the cabinet. Each government is required to define the broad outline of its policies in a programme, and present it to the Assembly for a mandatory period of debate. The failure of the Assembly to reject the government programme by an absolute majority of deputies confirms the cabinet in office.

Parliament

The Assembly of the Republic, in Lisbon, is the national parliament of Portugal. It is the main legislative body, although the Government also has limited legislative powers.

The Assembly of the Republic is a unicameral body composed of up to 230 deputies. Elected by universal suffrage according to a system of closed party-list proportional representation, deputies serve four-year terms of office, unless the President dissolves the Assembly and calls for new elections.

Currently the Government (PS) has an absolute majority of seats in Parliament. The PSD is the main opposition party, alongside Chega, Liberal Initiative, BE, PCP, PAN and Livre.

Foreign relations

A member state of the United Nations since 1955, Portugal is also a founding member of NATO (1949), OECD (1961) and EFTA (1960); it left the last in 1986 to join the European Economic Community, which became the European Union in 1993.

In 1996, Portugal co-founded the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organization and political association of Lusophone nations across four continents, where Portuguese is an official language. The global headquarters of the CPLP is in Penafiel Palace, in Lisbon.

António Guterres, who has served as Prime Minister of Portugal from 1995 to 2002 and UN High Commissioner for Refugees from 2005 to 2015, assumed the post of UN Secretary-General on 1 January 2017; making him the first Secretary-General from Western Europe since Kurt Waldheim of Austria (1972–1981), the first former head of government to become Secretary-General and the first Secretary-General born after the establishment of the United Nations on 26 June 1945.

In addition, Portugal was a full member of the Latin Union (1983) and the Organization of Ibero-American States (1949). It has a friendship alliance and dual citizenship treaty with its former colony, Brazil. Portugal and the United Kingdom share the world's oldest active military accord through their Anglo-Portuguese Alliance (Treaty of Windsor), which was signed in 1373.

There are two international territorial disputes, both with Spain:

- Olivenza. Under Portuguese sovereignty since 1297, the municipality of Olivença was ceded to Spain under the Treaty of Badajoz in 1801, after the War of the Oranges. Portugal claimed it back in 1815 under the Treaty of Vienna. However, since the 19th century, it has been continuously ruled by Spain which considers the territory theirs not only de facto but also de jure.[141]

- The Ilhas Selvagens (Savage Islands), a small group of mostly uninhabited islets which fall under Portuguese Madeira's regional autonomous jurisdiction. Found in 1364 by Italian mariners under the service of Prince Henry The Navigator,[142] it was first noted by Portuguese navigator Diogo Gomes de Sintra in 1438. Historically, the islands have belonged to private Portuguese owners from the 16th century on, until 1971[143] when the government purchased them and established a natural reserve area covering the whole archipelago. The islands have been claimed by Spain since 1911,[144] and the dispute has caused some periods of political tension between the two countries.[145] The main problem for Spain's attempts to claim these small islands, has been not so much their intrinsic value, but the fact that they expand Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone considerably to the south, in detriment of Spain.[146] The Selvagens Islands have been tentatively added to UNESCO's world heritage list in 2017.[147]

Military

The armed forces have three branches: Navy, Army and Air Force. They serve primarily as a self-defence force whose mission is to protect the territorial integrity of the country and provide humanitarian assistance and security at home and abroad. As of 2008, the three branches numbered 39,200 active personnel including 7,500 women. Portuguese military expenditure in 2009 was 5 billion US$,[148] representing 2.1 per cent of GDP. Military conscription was abolished in 2004. The minimum age for voluntary recruitment is 18 years.