Robert Mitchum

Robert Charles Durman Mitchum (August 6, 1917 – July 1, 1997) was an American actor. He is known for his antihero roles and film noir appearances. He received nominations for an Academy Award and a BAFTA Award. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1984 and the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1992. Mitchum is rated number 23 on the American Film Institute's list of the greatest male stars of classic American cinema.[1]

Robert Mitchum | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Mitchum in 1949 | |

| Born | Robert Charles Durman Mitchum August 6, 1917 Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1997 (aged 79) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1942–1995 |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Dorothy Spence

(m. 1940) |

| Children | 3, including James and Christopher Mitchum |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Mitchum rose to prominence with an Academy Award nomination for the Best Supporting Actor for The Story of G.I. Joe (1945). His best-known films include Out of the Past (1947), Angel Face (1953), River of No Return (1954), The Night of the Hunter (1955), Thunder Road (1958), Cape Fear (1962), El Dorado (1966), Ryan's Daughter (1970), The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), and Farewell, My Lovely (1975). He is also known for his television role as U.S. Navy Captain Victor "Pug" Henry in the epic miniseries The Winds of War (1983) and sequel War and Remembrance (1988).

Film critic Roger Ebert called Mitchum his favorite movie star and the soul of film noir: "With his deep, laconic voice and his long face and those famous weary eyes, he was the kind of guy you'd picture in a saloon at closing time, waiting for someone to walk in through the door and break his heart."[2] David Thomson wrote: "Since the war, no American actor has made more first-class films, in so many different moods."[3]

Early life

Robert Charles Durman Mitchum was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on August 6, 1917, into a Methodist family of Scottish-Irish, Native American, and Norwegian descent.[4][5] His father, James Thomas Mitchum, a shipyard and railroad worker, was of Scottish-Irish and Native American descent,[4][6][note 1] and his mother, Ann Harriet Gunderson, was a Norwegian immigrant and sea captain's daughter.[6][9] His older sister, Annette (known as Julie Mitchum during her acting career),[10] was born in 1914.[11] James was crushed to death in a railyard accident in Charleston, South Carolina, in February 1919.[12] His widow, Ann, was pregnant at the time, and was awarded a government pension. She returned to Connecticut after staying for some time in her husband's hometown of Lane, South Carolina. Her third child, John, was born in September 1919.[12][note 2]

When all of the children were old enough to attend school, Ann found employment as a linotype operator for the Bridgeport Post.[14] She married Lieutenant Hugh "The Major" Cunningham Morris, a former Royal Naval Reserve officer. They had a daughter, Carol Morris, born c. 1928 on the family farm in Delaware.[15][16][17]

As a child, Mitchum was known as a prankster, often involved in fistfights and mischief.[18][19] In 1926, his mother sent him and his younger brother to live with her parents on a farm near Woodside, Delaware.[4][20] He attended Felton High School,[21] where he was expelled for mischief.[22] During his years at the Felton school, he ran away from home for the first time at age 11.[23][24]

In 1929, Mitchum and his younger brother were sent to Philadelphia to live with their older sister, Julie,[25] who had started her career as a performer in vaudeville acts on the East Coast.[26] The following year, he and the rest of the family moved to New York with Julie, sharing an apartment in Manhattan's Hell's Kitchen with her and her husband.[25][27] Mitchum attended Haaren High School[28] but was eventually expelled.[29]

Mitchum left home at age 14[30] and traveled throughout the country, hopping freight cars[31] and taking a number of jobs, including ditch-digging for the Civilian Conservation Corps and professional boxing.[18][32] In summer 1933, he was arrested for vagrancy in Savannah, Georgia and put in a local chain gang.[18][33][34][note 3] By Mitchum's account, he escaped and hitchhiked to Rising Sun, Delaware, where his family had moved.[18][35] That fall, at age 16, while recovering from injuries that nearly cost him a leg, he met 14-year-old Dorothy Spence, whom he would later marry.[36][33][37] He soon went back on the road, eventually "riding the rails" to California.[38][39][40]

Acting career

Getting established

In the mid-1930s Julie Mitchum moved to the West Coast in the hope of acting in movies, and the rest of the Mitchum family soon followed her to Long Beach, California. Robert arrived in 1936. During this time, Mitchum worked as a ghostwriter for astrologer Carroll Righter. Julie persuaded him to join the local theater guild with her. At The Players Guild of Long Beach, Mitchum worked as a stagehand and occasional bit-player in company productions. He also wrote several short pieces which were performed by the guild. According to Lee Server's biography (Robert Mitchum: Baby, I Don't Care), Mitchum put his talent for poetry to work writing song lyrics and monologues for Julie's nightclub performances.

In 1940, he returned to Delaware to marry Dorothy Spence, and they moved back to California. He gave up his artistic pursuits at the birth of their first child James, nicknamed Josh, and two more children, Chris and Petrine, followed. Mitchum found steady employment as a machine operator during World War II with the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, but the noise of the machinery damaged his hearing.[40][41] He also suffered a nervous breakdown (which resulted in temporary vision problems), due to job-related stress.[42]

He then sought work as a film actor, performing initially as an extra and in small speaking parts. His agent got him an interview with Harry Sherman, the producer of Paramount's Hopalong Cassidy western film series, which starred William Boyd; Mitchum was hired to play minor villainous roles in several films in the series during 1942 and 1943. He went uncredited as a soldier in the 1943 film The Human Comedy starring Mickey Rooney. His first on-screen credit came in 1943 as a Marine private in the Randolph Scott war film Gung Ho![43] Mitchum continued to find work as an extra and supporting actor in numerous productions for various studios.

After impressing director Mervyn LeRoy during the making of Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, Mitchum signed a seven-year contract with RKO Radio Pictures. He was groomed for B-Western stardom in a series of Zane Grey adaptations.[40] Following the moderately successful Western Nevada, RKO lent Mitchum to United Artists for a prominent supporting actor role in The Story of G.I. Joe (1945). In the film, he portrayed war-weary officer Bill Walker (based on Captain Henry T. Waskow), who remains resolute despite the troubles he faces. The film, which followed the life of an ordinary soldier through the eyes of journalist Ernie Pyle (played by Burgess Meredith), became an instant critical and commercial success. Shortly after filming, Mitchum was drafted into the United States Army, serving at Fort MacArthur, California, as a medic. At the 1946 Academy Awards, The Story of G.I. Joe was nominated for four Oscars, including Mitchum's only nomination for an Academy Award, for Best Supporting Actor. He finished the year with a Western (West of the Pecos) and a story of returning Marine veterans (Till the End of Time), before migrating to a genre that came to define Mitchum's career and screen persona: film noir.

Film noir

Mitchum ultimately became best known for his work in film noir. His first foray into crime drama was a supporting role in the 1944 B-movie When Strangers Marry, about newlyweds and a New York City serial killer.[44] Another early noir, Undercurrent (1946), featured him as a troubled, sensitive man entangled in the affairs of his tycoon brother (Robert Taylor) and his brother's suspicious wife (Katharine Hepburn).[45] John Brahm's The Locket (1946) featured Mitchum as a bitter ex-boyfriend to Laraine Day's femme fatale.[46] Raoul Walsh's Pursued (1947) combined the Western and noir genres, with Mitchum's character attempting to recall his past and find those responsible for killing his family.[47] Crossfire (also 1947) featured Mitchum as a member of a group of returned World War II soldiers embroiled in a murder investigation for an act committed by an anti-Semite in their ranks. The film, directed by Edward Dmytryk and starring (in order of billing) Robert Young, Mitchum and Robert Ryan, earned five Academy Award nominations.[48][40]

Following Crossfire, Mitchum starred in Out of the Past (also called Build My Gallows High),[49] widely regarded as one of the greatest of all films noir.[50][51][52][53] Directed by Jacques Tourneur and featuring the cinematography of Nicholas Musuraca, the picture featured Mitchum in his best-known noir role, Jeff Markham, a small-town gas-station owner and former investigator whose unfinished business with gambler Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas) and femme fatale Kathie Moffett (Jane Greer) comes back to haunt him.[49]

On September 1, 1948, after a string of successful films for RKO, Mitchum and actress Lila Leeds were arrested for possession of marijuana.[54] The bust was the result of a sting operation designed to capture other Hollywood partiers as well. After serving a week at the county jail (he described the experience to a reporter as being "like Palm Springs, but without the riff-raff"), Mitchum spent 43 days (February 16 to March 30) at a Castaic, California, prison farm. Life photographers were permitted to take photos of him mopping up in his prison uniform.[55] The arrest inspired the exploitation film She Shoulda Said No! (1949), which starred Leeds.[56] Mitchum's conviction was later overturned by the Los Angeles court and district attorney's office on January 31, 1951, after being exposed as a setup.[57][58]

Despite Mitchum's legal troubles his popularity was not harmed and films released immediately after his arrest were box-office hits. Rachel and the Stranger (1948) featured Mitchum in a supporting role as a mountain man competing for the hand of Loretta Young, the indentured servant and wife of William Holden.[59] In the film adaptation of John Steinbeck's novella The Red Pony (1949), he appeared as a trusted cowhand to a ranching family.[60] He returned to film noir in a reunion later that year with Jane Greer in The Big Steal (also 1949), an early Don Siegel film.[61]

By the end of the 1940s, Mitchum had become RKO's biggest star.[62][63]

Mainstream stardom in the 1950s and 1960s

.jpg.webp)

In the noir Where Danger Lives (1950), Mitchum played a doctor who comes between a mentally unbalanced Faith Domergue and cuckolded Claude Rains.[64] The Racket was a noir remake of the early crime drama The Racket (1928), and featured Mitchum as a police captain fighting corruption in his precinct.[65] It was one of RKO's most successful films of 1951.[66] The Josef von Sternberg noir, Macao (1952), had Mitchum as a victim of mistaken identity at an exotic resort casino, playing opposite Jane Russell.[67] Otto Preminger's noir Angel Face was the first of three film collaborations between Mitchum and British stage actress Jean Simmons. Mitchum plays an ambulance driver who allows a murderously insane heiress to fatally seduce him.[68]

Mitchum was fired from Blood Alley (1955) over his conduct, reportedly having thrown the film's transportation manager into San Francisco Bay. According to Sam O'Steen's memoir Cut to the Chase, Mitchum showed up on-set after a night of drinking and tore apart a studio office when they did not have a car ready for him. Mitchum walked off the set of the third day of filming Blood Alley, claiming he could not work with the director. Because Mitchum was showing up late and behaving erratically, producer John Wayne, after failing to obtain Humphrey Bogart as a replacement, took over the role himself.[69][70]

Following a series of conventional Westerns and films noir, as well as the Marilyn Monroe adventure vehicle River of No Return (1954),[71] Mitchum appeared in The Night of the Hunter (1955), Charles Laughton's only film as director. Based on a novel by Davis Grubb, the noir thriller starred Mitchum as a monstrous criminal posing as a preacher to find money hidden by his cellmate in the man's home.[72] His performance as Reverend Harry Powell is considered by many to be one of the best of his career.[72][73][74][75][76][77] Stanley Kramer's melodrama Not as a Stranger, also released in 1955, starred Mitchum against type, as an idealistic young doctor, who marries an older nurse (Olivia de Havilland), only to question his morality many years later. The film was a box-office hit, but the critical reactions were mixed, with film critic Leslie Halliwell pointing out that all of the actors were too old for their characters.[78]

On March 8, 1955, Mitchum formed DRM (Dorothy and Robert Mitchum) Productions to produce five films for United Artists; four ultimately were produced.[79][80] The first film was Bandido (1956).[81] Following a succession of average Westerns and the poorly received noir Foreign Intrigue (1956),[82] Mitchum starred in the first of three theatrical films with Deborah Kerr.[83] The John Huston war drama Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, cast Mitchum as a Marine corporal shipwrecked on a Pacific Island with a nun, Sister Angela (Kerr), as his sole companion. In this character study they struggle with the elements, the Japanese garrison, and their growing feelings for one another. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards, including Best Actress and Best Adapted Screenplay.[84] For his role, Mitchum was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actor.[85] In the World War II submarine classic The Enemy Below (1956), Mitchum played the captain of a US Navy destroyer who matches wits with a wily German U-boat skipper Curt Jurgens;[86] both men would also appear in the 1962 World War II epic The Longest Day.[87][88]

Thunder Road (1958), the second DRM Production,[79] was loosely based on an incident in which a driver transporting moonshine was said to have fatally crashed on Kingston Pike in Knoxville, Tennessee, somewhere between Bearden Hill and Morrell Road. According to Metro Pulse writer Jack Renfro, the incident occurred in 1952 and may have been witnessed by James Agee, who passed the story on to Mitchum.[89] He starred, produced, co-wrote the screenplay,[90] and is rumored to have directed much of the film.[91][89] It costars his son James, as his on-screen brother.[90][note 4] Mitchum also co-wrote (with Don Raye) the theme song, "The Ballad of Thunder Road."[98][99][100]

Mitchum returned to Mexico for The Wonderful Country (1959) with Julie London,[101] and Ireland for A Terrible Beauty/The Night Fighters for the last of his DRM Productions.[102][103]

Mitchum and Kerr reunited for the Fred Zinnemann film The Sundowners (1960), playing an Australian husband and wife struggling in the sheep industry during the Depression. The film received five Oscar nominations,[104] and Mitchum earned the year's National Board of Review award for Best Actor for his performance. The award also recognized his performance in the Vincente Minnelli rural drama Home from the Hill (also 1960).[105] He was teamed with former leading ladies Kerr and Simmons, as well as Cary Grant, for the Stanley Donen comedy The Grass Is Greener the same year.[106]

Mitchum's performance as the menacing rapist Max Cady in the 1962 noir Cape Fear brought him further renown for playing cold, predatory characters.[107] The 1960s were marked by a number of lesser films. He was one of the all-star husbands of Shirley MacLaine in the comedy What a Way to Go! (1964),[108] the drunken sheriff in the Howard Hawks Western El Dorado (1967), a quasi-remake of Rio Bravo (1959),[109][40] and another WWII epic, Anzio (1968).[110] He co-starred with Dean Martin in the 1968 Western 5 Card Stud, playing a homicidal preacher.[111]

Mitchum turned down The Wild Bunch partially because he did not want to work with Sam Peckinpah.[112]

1970s

.jpg.webp)

Mitchum made a departure from his typical screen persona with the 1970 David Lean film Ryan's Daughter, in which he starred as Charles Shaughnessy, a mild-mannered schoolmaster in World War I–era Ireland.[113] At the time of filming, Mitchum's recent films had been critical and commercial flops, and he was going through a personal crisis that had him considering suicide. Screenwriter Robert Bolt told him that he could do so after the film was finished and that he would personally pay for his burial.[114][115][116] Though the film was nominated for four Academy Awards (winning two)[113] and Mitchum was much publicized as a contender for a Best Actor nomination, he was not nominated.[117][118] George C. Scott won the award for his powerful performance in Patton,[118] a project Mitchum had rejected as glorifying war. Mitchum said that Patton and Dirty Harry, another picture he turned down, were movies he would not do for any amount of money because he disagreed with the morality of the scripts.[119]

The 1970s featured Mitchum mainly in crime dramas, to mixed result. The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) had the actor playing an aging Boston hoodlum caught between the Feds and his criminal friends.[120] Sydney Pollack's The Yakuza (1974) transplanted the typical film noir story arc to the Japanese underworld.[121] Mitchum's stint as an aging Philip Marlowe in the Raymond Chandler adaptation Farewell, My Lovely (1975) (a remake of 1944's Murder My Sweet) was sufficiently well received by audiences and critics[122] for him to reprise the role in 1978's The Big Sleep, a remake of the 1946 film of the same title.[123]

Mitchum also appeared in 1976's Midway about a crucial 1942 World War II battle.[124]

Later work

In 1982, Mitchum played Coach Delaney in the film adaptation of playwright/actor Jason Miller's 1973 Pulitzer Prize-winning play That Championship Season.[125]

Mitchum expanded to television work with the 1983 miniseries The Winds of War. The big-budget Herman Wouk story aired on ABC, starring Mitchum as naval officer "Pug" Henry and Victoria Tennant as Pamela Tudsbury, and examined the events leading up to America's involvement in World War II. It was watched by 140 million people over seven days and became the most-watched miniseries up to that point.[126][127] He returned to the role in 1988's War and Remembrance,[40] which continued the story through the end of the war.[128]

In 1984, Mitchum entered the Betty Ford Center in Palm Springs, California for treatment of alcoholism.[129]

He played George Hazard's father-in-law in the 1985 miniseries North and South, which also aired on ABC.[130]

Mitchum starred opposite Wilford Brimley in the 1986 made-for-TV movie Thompson's Run.[131]

In 1987, Mitchum was the guest host on Saturday Night Live, where he played private eye Philip Marlowe for the last time in the parody sketch, "Death Be Not Deadly." The show ran a short comedy film he made (written and directed by his daughter, Petrine) called Out of Gas, a mock sequel to Out of the Past (Jane Greer reprised her role from the original film).[132][133] He also was in Richard Donner's 1988 comedy Scrooged.[134]

In 1991, Mitchum was set to receive a lifetime achievement award from the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. He rejected it, however, after learning that he would have to pay for his own transport and accommodations and accept it in person.[135][note 5] In the same year, he received the Telegatto award and, in 1992, the Cecil B. DeMille Award from the Golden Globe Awards.[137][138][40]

Mitchum continued to appear in films until the mid-1990s, such as Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man,[139] and he narrated the Western Tombstone.[140] In contrast to his role as the antagonist in the original, he played the protagonist police detective in Martin Scorsese's remake of Cape Fear,[141] but the actor gradually slowed his workload. His last film appearance was a small but pivotal role in the television biographical film, James Dean: Race with Destiny, playing Giant director George Stevens.[139] Mitchum's last starring role was in the 1995 Norwegian movie Pakten.[142] [40]

Music

One of the lesser-known aspects of Mitchum's career was his foray into music as a singer. Critic Greg Adams writes, "Unlike most celebrity vocalists, Robert Mitchum actually had musical talent."[143]

Mitchum's voice was often used instead of that of a professional singer when his character sang in his films. Notable productions featuring Mitchum's own singing voice included Pursued, Rachel and the Stranger, River of No Return, The Night of the Hunter, and The Sundowners.[144] He sang the title song to the Western Young Billy Young, made in 1969.[145]

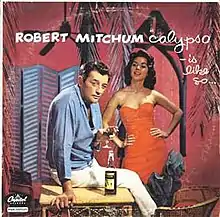

Mitchum recorded two albums. After hearing traditional calypso music and meeting artists such as Mighty Sparrow and Lord Invader while filming Fire Down Below and Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison in the Caribbean islands of Tobago, he recorded Calypso – is like so ... in March 1957. On the album, released through Capitol Records, he emulated the calypso sound and style, even adopting the style's unique pronunciations and slang.[144][146][147][148] A year later, he recorded a song he had written for the film Thunder Road, titled "The Ballad of Thunder Road".[98] The country-style song became a modest hit for Mitchum, reaching number 62 on the Billboard Pop Singles chart in September 1958.[98][99] The song was included as a bonus track on a successful reissue of Calypso ...[149][148] and helped market the film to a wider audience.

Although Mitchum continued to use his singing voice in his film work, he waited until 1967 to record his follow-up record, That Man, Robert Mitchum, Sings. The album, released by Nashville-based Monument Records, took him further into country music, and featured songs similar to "The Ballad of Thunder Road".[150][151] "Little Old Wine Drinker Me", the first single, was a top-10 hit at country radio, reaching number nine there, and crossed over onto mainstream radio, where it peaked at number 96.[152] Its follow-up, "You Deserve Each Other", also charted on the Billboard Country Singles chart.[152] Mitchum was nominated for an Academy of Country Music Award for Most Promising Male Vocalist in 1968.[153]

Albums

| Year | Album | U.S. Country | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Calypso—is like so ... | — | Capitol |

| 1967 | That Man Robert Mitchum ... Sings | 35 | Monument |

Singles

| Year | Single | Chart positions | Album | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Country | U.S. | |||

| 1958 | "The Ballad of Thunder Road" | — | 62[98] | That Man Robert Mitchum ... Sings |

| 1962 | "The Ballad of Thunder Road" (re-release) | — | 65[98] | |

| 1967 | "Little Old Wine Drinker Me" | 9[152] | 96[152] | |

| "You Deserve Each Other" | 55[152] | — | ||

Personal life

Marriage and family

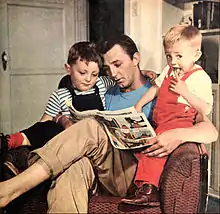

Mitchum married his childhood sweetheart, Dorothy Spence, whom he met when he was 16 and she was 14, in Dover, Delaware, on March 16, 1940.[154][37] The couple had three children: sons, James (born May 8, 1941)[155] and Christopher (born October 16, 1943),[156] both actors; and a daughter, Petrine (born March 3, 1952),[157][158] a writer.[154][37]

Despite his reported affairs with other women including actresses Lucille Ball,[159] Ava Gardner,[160] Jean Simmons,[161] Shirley MacLaine,[162] and Sarah Miles,[163] Mitchum and wife Dorothy remained together until his death in 1997.[154][37] He told journalist Don Short in a 1977 interview: "Not as though there has been anyone else in my life except Dorothy. There's not one of 'em—and I've met the best of 'em—worth lighting a candle for alongside her."[164]

Mitchum's grandchildren Bentley Mitchum and Carrie Mitchum are actors,[165] and another grandson, Kian Mitchum, a model.[166] His great-granddaughter Grace Van Dien is an actress.[165][167]

Friendships

Mitchum's close friends included Jane Russell, his neighbor in Santa Barbara, California;[168] and Deborah Kerr, his favorite costar.[169]

Political views

Mitchum was a Republican who campaigned for Barry Goldwater in the 1964 United States presidential election,[170] and considered him to be the only honest politician. According to a 2012 interview with his son Chris, conducted by Breitbart News, Mitchum also supported Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush in 1992.[171]

Death

A lifelong heavy smoker, Mitchum died in his sleep at 5 a.m. on July 1, 1997, at his home in Santa Barbara, California, from complications of lung cancer and emphysema.[9][154][172] His wife of 57 years, Dorothy, was by his side.[172][173] His body was cremated and, on July 6, his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean off the coast near his home.[174][175] The private ceremony was attended by only his family members and his longtime friend Jane Russell.[175][168] There is a cenotaph to him in his wife's family plot at the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Camden, Delaware.[176] His wife, Dorothy, died in 2014 (May 2, 1919, Camden, Delaware – April 12, 2014, Santa Barbara, California, aged 94).[37][177]

Controversies

At the 1982 premiere for That Championship Season, an intoxicated Mitchum assaulted a female reporter and threw a basketball that he was holding (a prop from the film) at a female photographer from Time magazine, injuring her neck and knocking out two of her teeth.[178][179] She sued him for $30 million in damages.[179] The suit eventually "cost him his salary from the film".[178]

Mitchum's role in That Championship Season may have indirectly contributed to another incident several months later. In a February 1983 Esquire interview, he made statements that some construed as racist, antisemitic and sexist. When asked if the Holocaust had occurred, Mitchum responded "so the Jews say."[178][180] Following the widespread negative response, he apologized a month later, saying that his statements were "prankish" and "foreign to my principle." He claimed that the problem had begun when he recited a purportedly racist monologue from his role in That Championship Season and the reporter believed that the words were Mitchum's. He claimed that he had only reluctantly agreed to the interview and then proceeded to "string... along" the reporter with his statements.[180]

Reception, acting style, and legacy

Mitchum is regarded by some critics as one of the finest actors of the Golden Age of Hollywood. David Thomson hailed Mitchum as one of the three "most important actors in film history" along with Cary Grant and Barbara Stanwyck.[181] Appraising Mitchum’s career, Thomson wrote: "Since the war, no American actor has made more first-class films, in so many different moods."[3] Roger Ebert wrote:

Robert Mitchum was my favorite movie star because he represented, for me, the impenetrable mystery of the movies. He knew the inside story. With his deep, laconic voice and his long face and those famous weary eyes, he was the kind of guy you'd picture in a saloon at closing time, waiting for someone to walk in through the door and break his heart.

Mitchum was the soul of film noir.[2]

Mitchum, however, was self-effacing; in an interview with Barry Norman for the BBC about his contribution to cinema, Mitchum stopped Norman in mid-flow and in his typical nonchalant style, said, "Look, I have two kinds of acting. One on a horse and one off a horse. That's it." He had also succeeded in annoying some of his fellow actors by voicing his puzzlement at those who viewed the profession as challenging and hard work.[182][183] He possessed a photographic memory that allowed him to remember lines with relative ease,[184][185][186][187] and was also known for his proficiency with accents.[188][189][190]

Director Robert Wise recalled that during the shooting of Blood on the Moon, Mitchum would mark his script with the letters "NAR," which meant "no action required." He told Wise that he didn't need a line and would give Wise a look instead.[191] Dismissive of method acting, when asked by George Peppard if he had studied it during filming of Home from the Hill, Mitchum jokingly responded that he had studied the “Smirnoff method”.[192]

This is not a tough job. You read a script. If you like the part and the money is O.K., you do it. Then you remember your lines. You show up on time. You do what the director tells you to do. When you finish, you rest and then go on to the next part. That's it.

—Mitchum's views on acting.[193]

Mitchum's subtle and understated acting style sometimes garnered him criticism of sleepwalking through his performances in the early stage of his career.[194] In his contemporary review of Out of the Past, James Agee commented that Mitchum's "curious languor" in love scenes suggested "Bing Crosby supersaturated with barbiturates."[195][196] The review of Where Danger Lives in the Monthly Film Bulletin in 1951 said, "Robert Mitchum performs somnambulistically."[197] David Thomson noticed that Mitchum "began to attract respectable attention" around the late 1950s.[198] Writing for the Village Voice in 1973, Andrew Sarris pointed out that Mitchum, with his stoic presence on the screen that was "mistaken for a stone face without feelings," had been "grossly maligned as an actor," while he was actually "reborn in every movie, recreated in every relationship."[50]

Mitchum had a solid reputation among the directors who worked with him. William A. Wellman thought Mitchum should have won the Academy Award for The Story of G.I. Joe and called him "one of the finest, most solid and real actors" in the world.[199] Charles Laughton, who directed him in The Night of the Hunter, considered Mitchum to be one of the best actors in the world and believed that he would have been the greatest Macbeth.[188] John Huston felt that Mitchum was on the same pedestal of actors such as Marlon Brando, Richard Burton and Laurence Olivier.[200] Vincente Minnelli wrote that few actors he had worked with brought "so much of themselves to a picture," and none did it "with such total lack of affectation" as Mitchum did.[201] Howard Hawks praised Mitchum for being a hard worker, labeling the actor a "fraud" for pretending to not care about acting.[202][203] David Lean said of Mitchum: "He is a master of stillness. Other actors act. Mitchum is. He has true delicacy and expressiveness, but his forte is his indelible identity. Simply by being there, Mitchum can make almost any other actor look like a hole in the screen."[204]

Mitchum's close friend and co-star on four movies, Deborah Kerr, commented on his acting abilities: "He makes acting seem like it's absolutely real. There's no acting to it at all. It's like falling off a log for him." Jane Greer, his co-star in Out of the Past and The Big Steal, said of him: "Bob would never be caught acting. He just is."[205]

Robert De Niro, Clint Eastwood,[206] Michael Madsen,[207] and Mark Rylance[208] have cited Mitchum as one of their favorite actors.

AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars lists Mitchum as the 23rd-greatest male star of classic Hollywood cinema.[1] AFI also recognized his performances as the menacing rapist Max Cady and Reverend Harry Powell as the 28th and 29th greatest screen villains of all time as part of AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains.[209]

Mitchum provided the voice of the famous American Beef Council commercials that touted "Beef ... it's what's for dinner", from 1992 until his death.[210][211]

A "Mitchum's Steakhouse" operated in Trappe, Maryland,[212] where Mitchum and his family lived from 1959 to 1965.[213]

Filmography

Notes

- According to Mitchum, his Native American ancestors came from South Carolina and both his paternal grandparents were half-Blackfoot Indian.[7][8]

- John later also became an actor.[13]

- Mitchum talked about his chain gang experience in the 1962 Saturday Evening Post interview: "I had hopped a freight train with about seventeen other kids and headed South. In my pocket I had thirty-eight dollars – all I had in the world. When we reached Savannah, I was cold and hungry. So I dropped off to get something to eat. The big fuzz grabbed me. 'For what?' I asked. He grinned. 'Vagrancy – we don't like Yankee bums around here.' When I told him I had thirty-eight dollars, he just called me a so-and-so wise guy and belted me with his club and ran me in."[18]

- According to Mitchum[92] and his son James,[93] Elvis Presley was to have played the film's lead, but his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, wanted him to focus on musicals, and Mitchum went on to star himself. However, some other sources say it was the part of Mitchum's on-screen brother that Elvis was considered for.[94][95][96][89] Elvis' friend George Klein recalled that Mitchum, who wrote the film's story, thought he and Elvis could do the film together, and Elvis was very excited about it. (Klein did not specify which role was intended for Elvis.)[97]

- Mitchum had been living in Santa Barbara, California since 1978[136] and the ceremony was to be held in New York. The award eventually went to Lauren Bacall instead.[135]

References

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (July 13, 1997). "Darkness and Light". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- Thomson 2014, p. 719.

- Roberts 1992, p. 12.

- Server 2001, p. 5.

- Server 2001, p. 3.

- Cavett 1971.

- Roberts 2000, p. 115.

- "Robert Mitchum, 79, Dies; Actor With Rugged Dignity". The New York Times. July 2, 1997. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Server 2001, p. 68.

- Server 2001, p. 4.

- Server 2001, pp. 5–6.

- McLellan, Dennis (December 3, 2001). "Actor John Mitchum, 82, Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Server 2001, p. 8.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 5–6.

- Eells 1984, pp. 17–18, 21.

- Server 2001, pp. 10–11, 17.

- Davidson, Bill (August 25, 1962). "The Many Moods of Robert Mitchum" (PDF). The Saturday Evening Post. Indianapolis, Indiana: Curtis Publishing Company. pp. 58–70. ISSN 0048-9239. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2013.

- Server 2001, pp. 11, 14–15.

- Server 2001, p. 12.

- Server 2001, p. 13.

- Server 2001, pp. 17–18.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 12, 25.

- Server 2001, p. 16.

- Roberts 1992, p. 25.

- Server 2001, p. 19.

- Server 2001, pp. 19–20.

- Server 2001, p. 20.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 7–8.

- Server 2001, pp. 23–24.

- Server 2001, pp. 25–26.

- Server 2001, pp. 28, 34–35, 40.

- Roberts 1992, p. 13.

- Champlin, Charles (October 2, 1994). "One Icon, Hard-Boiled". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- Eells 1984, pp. 29–30.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 22–24.

- "Dorothy Mitchum, Widow of Actor Robert Mitchum, Dies at 94". Variety. April 16, 2014. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 25–28.

- Server 2001, p. 35.

- "Biography: Robert Mitchum". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Obituary – Robert Mitchum Actor played tough guys". The Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa, Ontario. July 2, 1997. p. A-11. ProQuest 240116189.

- Server, Lee (March 6, 2002). Robert Mitchum: "Baby I Don't Care". Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-28543-2. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Bugs Bunny-War Bonds, 1943, retrieved September 21, 2017

- Roberts 1992, pp. 48–49.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 57–58.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 58–59.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 59–60.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 61–63.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 64–66.

- Sarris, Andrew (July 26, 1973). "He Does Something Different". The Village Voice. pp. 61–62.

- Ebert, Roger (July 18, 2004). "Out of the Past". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- Phipps, Keith (September 15, 2014). "Out of the Past". The Dissolve. Archived from the original on September 17, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- Feaster, Felicia; Miller, John M. (January 18, 2011). "The Essentials - Out of the Past". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 2, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- "Robert Mitchum Arrested with Two Movie Actresses in Marijuana Party Raid." Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine St. Petersburg Times, September 2, 1948.

- "Mitchum images." Archived November 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine sprintmail.com. Retrieved: October 10, 2012.

- Mitchum's upcoming film Rachel and the Stranger was rushed to completion to take advantage of the publicity surrounding the arrest. Rachel and the Stranger at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "Mitchum Conviction Expunged". The New York Times. February 1, 1951. p. 21. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 94–97.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 66–67.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 69–70.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 70–72.

- Jewell & Harbin 1982, p. 226.

- Longworth 2018, p. 331.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 73–74.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 76–77.

- Jewell & Harbin 1982, p. 254.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 78–79.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 33–34, 82–83.

- O'Steen & O'Steen 2001, p. 11.

- Olson & Roberts 1997, p. 417.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 86–88.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 91–94.

- "The Night of the Hunter (1955)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Malcolm, Derek (April 7, 1999). "Big Bad Bob". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Nixon, Rob; Stafford, Jeff (January 4, 2008). "The Essentials - The Night of the Hunter". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Ramon, Alexander (July 28, 2009). "Part 2: The Dark Side: 100 Essential Male Film Performances". PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- Ebert, Roger (November 24, 1996). "Great Movie: The Night of the Hunter". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 90–91.

- Roberts 2000, pp. 142, 208.

- Server 2001, pp. 287, 298, 337, 346.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 96–97.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 95–96.

- Roberts 1992, p. 33.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 97–99.

- "BAFTA Awards Database: Film | Foreign Actor in 1958". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 100–101.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 117–19.

- The Longest Day (1962), Turner Classic Movies Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: March 20, 2015.

- Clavin 2010, p. 143.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 101–3.

- Server 2001, p. 328.

- Roberts 2000, p. 139.

- "A Q&A with actor James Mitchum". Knoxville News Sentinel. June 15, 2008. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Server 2001, pp. 323–24.

- Stafford, Jeff (August 25, 2003). "Thunder Road". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Barnes, Mike (April 15, 2014). "Dorothy Mitchum, Widow of Actor Robert Mitchum, Dies at 94". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Klein & Crisafulli 2011, p. 78.

- Roberts 1992, p. 214.

- Server 2001, p. 325.

- "Don Raye". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 105–7.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 110–11.

- "The Night Fighters". Archived December 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: March 20, 2015.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 112–14.

- Roberts 1992, p. 109.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 111–12.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 115–17.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 124–26.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 129–31.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 131–32.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 133–34.

- Roberts 2000, p. 164.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 138–40.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 182–83.

- Eells 1984, pp. 244–45.

- Robert Mitchum on being an actor in a 1971 interview. Youtube.com. May 16, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- Marill 1978, p. 42.

- Eells 1984, p. 252.

- Roberts 2000, p. 83.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 143–44.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 144–46.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 146–49.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 153–54.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 149–50.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 157–58.

- Margulies, Lee (February 16, 1983). "'Winds' Becomes Most-Seen Miniseries". Los Angeles Times. p. G9.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 169–72.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 178–80.

- Thomas, Bob (October 10, 1985). "Robert Mitchum: An Irrepressible Patriarch of Actors". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 176–77.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 177–78.

- Roberts 1992, p. 196.

- Server 2001, pp. 514–15.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 162–63.

- Server 2001, p. 522.

- Server 2001, p. 473.

- "'Beauty and the Beast,' 'Bugsy,' Win Golden Globes". Los Angeles Times. January 19, 1992. p. B4. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- "Robert Mitchum". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on June 13, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Server 2001, p. 529.

- Server 2001, p. 524.

- Server 2001, pp. 521–22.

- Server 2001, pp. 526–28.

- Adams, Greg. "That Man, Robert Mitchum, Sings Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- Roberts 1992, p. 212.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 136–37.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 132–33.

- Server 2001, p. 318.

- Collar, Matt. "Calypso Is Like So... Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- "Calypso - Is Like So..." Amazon.com. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 214–15.

- Server 2001, pp. 409–10.

- Roberts 1992, p. 215.

- "ACM Winners Database: Robert Mitchum". Academy of Country Music. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Wilson, Jeff (July 1, 1997). "Screen Tough Guy Robert Mitchum Dies at 79". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 12, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Tomkies 1973, p. 40.

- Tomkies 1973, p. 49.

- "New Daughter for Mitchums". Los Angeles Times. March 4, 1952. p. 10.

- Tomkies 1973, p. 106.

- Server 2001, p. 72.

- Server 2001, pp. 206–7.

- Capua 2022, pp. 57–58.

- Willman, Chris (March 30, 2015). "TCM Film Fest: Shirley MacLaine Serves Up Barbs and Valentines". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- O'Sullivan, Majella (March 18, 2016). "'I Was So Innocent in the 60s, but Robert Mitchum Corrupted Me'". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Roberts 2000, pp. 168–69.

- Turner Classic Movies 2006, p. 151.

- "Kian Mitchum". The Fashion Spot. April 28, 2007. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008.

- Yahr, Emily (August 1, 2022). "Hollywood 'Nepo Babies' Know What You Think of Them. They Have Some Thoughts". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- Turner Classic Movies 2008, p. 128.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 33, 98.

- Knap, Ted (Scripps Howard). "Goldwater Leading in Citizen Groups; More—And More Varied—Than LBJ's". The Pittsburgh Press. October 22, 1964. p. 17. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- Gagliasso, Dan (March 31, 2012). "BH Interview: Liberal Blacklist Couldn't Stop Chris Mitchum". Breibart News. "You would think that an actor with such an ingrained bad boy image as Robert Mitchum would have leaned far to the left, but his son dispels any misconceptions. 'Dad did campaign stuff for Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan and H. W. Bush. He was all about personal freedom and responsibility,' he says." Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- Server 2001, p. 533.

- "UPI Focus: Robert Mitchum Dead at 79". United Press International. July 1, 1997. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Snow, Shauna (July 10, 1997). "Arts and entertainment reports from The Times, national and international news services and the nation's press". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Server 2001, p. 535.

- Wilson 2016, p. 521.

- "Dorothy Clements Spence Mitchum". Santa Barbara Independent. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- Maslin, Janet (March 12, 2001). "Books of the Times: The Swaggering Life of a Movie Idol". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015.

- "Actor Robert Mitchum, being sued for $30 million by..." UPI. January 27, 1984. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018.

- "Mitchum Says He is 'sorry' About the 'misunderstanding' Caused by His Interview". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. March 17, 1983. Archived from the original on July 27, 2017.

- Thomson 2014, p. x.

- ": Mad, bad and dangerous to know." Archived January 10, 2012, at Wikiwix Byronic. Retrieved: October 10, 2012.

- "Pin-up: Robert Mitchum." Archived May 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine lucyterberg.co, October 22, 2011. Retrieved: October 10, 2012.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 142, 197.

- Ray & Ray 1993, p. 105.

- Roberts 2000, p. 189.

- Server 2001, p. 7.

- Lawrenson, Helen (May 1, 1964). "The Man Who Never Got to Speak for National Youth Day". Esquire. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 177–78.

- Ebert, Roger (July 2, 1997). "The Last of the Old Lions". Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- Sandford, Christopher (August 8, 2017). "Missing Robert Mitchum: Nostalgia for the Archetypal American Male". America. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- Server 2001, pp. 344–45.

- King, Larry (March 25, 1991). "Sharing the Fantasy and Facts of Acting the Part". USA Today. p. 2D.

- Cwik, Greg (September 29, 2017). "The Curious Languor of Robert Mitchum". Mubi. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- Miller, John M. (January 18, 2011). "Critics' Corner - Out of the Past". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 2, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- "Cinema: The New Pictures". Time. December 15, 1947. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- "Where Danger Lives". Monthly Film Bulletin. British Film Institute. 18 (204): 208. January 1951.

- Thomson 2014, p. 720.

- Tomkies 1973, p. 55.

- Huston 1980, pp. 261–62.

- Minnelli & Arce 1974, p. 333.

- King, Susan (April 1, 1990). "The interview, Mitchum-style". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- McBride 2013, p. 169.

- Lewis, Grover (March 15, 1973). "Robert Mitchum: The Last Celluloid Desperado". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 25, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- Feldman & Winter 1991.

- Schickel 1996, p. 13.

- White, Adam (May 11, 2020). "Michael Madsen interview: 'Harvey Weinstein never liked me – he didn't want me in any of Tarantino's movies'". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Thompson, Kristin. "Mark Rylance, man of mystery". David Bordwell's Website on Cinema. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Moore, Martha T. (May 8, 1992). "Beef the Hero in Ads Again". USA Today. p. 2B.

- Kirk, Jim (July 4, 1997). "Mitchum's Memory Lives in Ads—for Now". Chicago Tribune. p. 3.

- "Mitchum's Steakhouse". Archived from the original on September 5, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- Tomkies 1973, pp. 138, 168–69.

General and cited sources

Books

- Capua, Michelangelo (2022). Jean Simmons: Her Life and Career. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-8224-2.

- Clavin, Tom (2010). That Old Black Magic: Louis Prima, Keely Smith, and the Golden Age of Las Vegas. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-821-7.

- Eells, George (1984). Robert Mitchum. New York and Toronto: Franklin Watts. ISBN 978-0-531-09836-3.

- Huston, John (1980). An Open Book. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-40465-3.

- Jewell, Richard B.; Harbin, Vernon (1982). The RKO Story. New York: Arlington House. ISBN 978-0-517-54656-7.

- Klein, George; Crisafulli, Chuck (2011). Elvis: My Best Man: Radio Days, Rock 'n' Roll Nights, and My Lifelong Friendship with Elvis Presley. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45275-7.

- Longworth, Karina (2018). Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes's Hollywood. New York: Custom House. ISBN 978-0-06-244051-8.

- Marill, Alvin H. (1978). Robert Mitchum on the Screen. South Brunswick and New York: A. S. Barnes and Company. ISBN 978-0-498-01847-3.

- McBride, Joseph (2013). Hawks on Hawks. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-4262-3.

- Minnelli, Vincente; Arce, Hector (1974). I Remember It Well. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 978-0-385-09522-8.

- Mitchum, John (1989). Them Ornery Mitchum Boys: The Adventures of Robert and John Mitchum. Pacifica, California: Creatures at Large. ISBN 978-0-940064-07-2.

- Olson, James; Roberts, Randy (1997). John Wayne: American. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-8970-3.

- O'Steen, Sam; O'Steen, Bobbie (2001). Cut to the Chase: Forty-Five Years of Editing America's Favorite Movies. Los Angeles, California: Michael Wiese Productions. ISBN 978-0-941188-37-1.

- Ray, Nicholas; Ray, Susan (1993). I was Interrupted: Nicholas Ray on Making Movies. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08233-5.

- Roberts, Jerry, ed. (2000). Mitchum: In His Own Words. New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-87910-292-0.

- Roberts, Jerry (1992). Robert Mitchum: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27547-0.

- Schickel, Richard (1996). Clint Eastwood: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-42974-6.

- Server, Lee (2001). Robert Mitchum: "Baby, I Don't Care". New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-28543-2.

- Thomson, David (2014). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (6th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-71184-8.

- Tomkies, Mike (1973) [First published 1972 by Henry Regnery Company]. The Robert Mitchum Story: "It Sure Beats Working". New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-23484-1.

- Turner Classic Movies (2006). Leading Men: The 50 Most Unforgettable Actors of the Studio Era. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5467-2.

- Turner Classic Movies (2008). Leading Couples: The Most Unforgettable Screen Romances of the Studio Era. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6301-8.

- Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (3rd ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7992-4.

Documentaries

- Feldman, Gene, and Suzette Winter (Directors) (1991). Robert Mitchum: The Reluctant Star (TV Movie). US: Wombat Productions.

- Monro, Gregory (Director) (2017). James Stewart, Robert Mitchum: The Two Faces of America (TV Movie). France and US: TS Productions.

- Benhamou, Stéphane (Director) (2018). Robert Mitchum, le mauvais garçon d'Hollywood (TV Movie) (in French). France: Arte.

- Weber, Bruce (Director) (2018). Nice Girls Don't Stay for Breakfast (Movie). US.

Interviews

- Mitchum, Robert (April 29, 1971). "The Dick Cavett Show: Robert Mitchum" (Interview). Interviewed by Dick Cavett. American Broadcasting Company.

- Mitchum, Robert; Russell, Jane (1996). "Private Screenings: Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell" (Interview). Interviewed by Robert Osborne. Turner Classic Movies.

External links

- Robert Mitchum at IMDb

- Robert Mitchum at the TCM Movie Database

- Profile at Turner Classic Movies

- Photographs and literature

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-12A (1966) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.