Kipunji

The kipunji (Rungwecebus kipunji), also known as the highland mangabey, is a species of Old World monkey that lives in the highland forests of Tanzania. The kipunji has a unique call, described as a 'honk-bark', which distinguishes it from its relatives, the grey-cheeked mangabey and the black crested mangabey, whose calls are described as 'whoop-gobbles'.

| Kipunji[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Subfamily: | Cercopithecinae |

| Tribe: | Papionini |

| Genus: | Rungwecebus Davenport, 2006 |

| Species: | R. kipunji |

| Binomial name | |

| Rungwecebus kipunji (Jones et al., 2005) | |

| |

| Kipunji range | |

The kipunji was independently discovered by researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society, the University of Georgia, and Conservation International, in December 2003 and July 2004, making it the first new African monkey species discovered since the sun-tailed monkey in 1984.[1] Originally assigned to the genus Lophocebus,[1][4] genetic and morphological data showed that it is more closely related to the baboons (genus Papio) than to the other mangabeys in the genus Lophocebus. Scientists subsequently assigned it to a new genus, Rungwecebus, named after Mount Rungwe, where it is found.[2] The kipunji is the first new monkey genus to be discovered since Allen's swamp monkey in 1923.[5]

Zoologists were initially skeptical of the existence of the kipunji until its discovery, as traditional tales of the Nyakyusa people described the monkey as both real and mythical.[6]

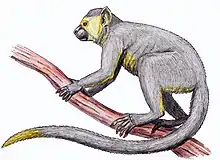

Physical description

Adult male kipunjis have been observed at a typical length of 85 to 90 cm and are estimated to weigh between 10 and 16 kg. The kipunji's relatively long pelage is light or medium brown with white on the end of the tail and the ventrum. The pelage close to the hands and feet tends to be a medium to dark brown. Its hands, feet, and face are all black. These primates do not appear to show any sexual dimorphism in relation to pelage coloration.[4][2]

One feature, in combination with their pelage coloration, that helps to separate kipunjis from their Cercocebus and Lophocebus relatives is the broad crest of hair on the crown of their heads.[2]

Distribution

Around 1,100 of the animals live in the highland Ndundulu Forest Reserve, adjacent to Udzungwa Mountains National Park, and in a disjunct population 250 miles away on Mount Rungwe and in Kitulo National Park, which is adjacent to it. The forest at Rungwe is highly degraded, and fragmentation of the remaining forest threatens to split that population into three smaller populations. The Ndundulu forest is in better shape, but the population there is smaller.

Conservation

The kipunji is classified as an endangered species by the IUCN.[3] In 2008, a Wildlife Conservation Society team found that the monkey's range is restricted to just 6.82 mi2 (17.7 km2) of forest in the two isolated regions, the Ndundulu forest and the Rungwe-Livingstone forest.[7] The Ndundulu forest is the smaller of the two and was found to support a population of 75 individuals, ranging from 15 to 25 individuals per group. The Rungwe-Livingstone forest is suspected to contain 1,042 individuals in Rungwe-Kitulo, ranging from 25 to 39 individuals per group. All areas where the kipunji is found are considered protected areas, but no management operations are currently in effect.

Several factors contribute to the projected decline of the species, including predation, habitat destruction, and hunting. The kipunji has only two known predators - crowned eagles (Stephanoaetus coronatus) and leopards (Panthera pardus). The biggest threats to the species come from human activities. Logging for timber and charcoal production are the most prominent threats, but locals are also known to hunt the kipunji due to its crop-destroying habits or simply as a food source. Continued habitat loss is anticipated to cause a loss of the Bujingijila Corridor that links two populations in the Mount Rungwe and Livingstone forests.

The species was included in the list of "The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates" in 2006 and 2008.[8]

References

- Jones, Trevor; Carolyn L. Ehardt; Thomas M. Butynski; Tim R. B. Davenport; Noah E. Mpunga; Sophy J. Machaga; Daniela W. De Luca (2005). "The Highland Mangabey Lophocebus kipunji: A New Species of African Monkey". Science. 308 (5725): 1161–1164. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1161J. doi:10.1126/science.1109191. PMID 15905399. S2CID 46580799.

- Davenport, Tim R. B.; William T. Stanley; Eric J. Sargis; Daniela W. De Luca; Noah E. Mpunga; Sophy J. Machaga; Link E. Olson (2006). "A New Genus of African Monkey, Rungwecebus: Morphology, Ecology, and Molecular Phylogenetics". Science. 312 (5778): 1378–81. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1378D. doi:10.1126/science.1125631. PMID 16690815. S2CID 38690218.

- Davenport, T. (2019). "Rungwecebus kipunji". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T136791A17961368. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T136791A17961368.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Jones, P. (May 20, 2005). "The Highland Mangabey Lophocebus kipunji: A new species of African monkey". Science. 308 (5725): 1161–4. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1161J. doi:10.1126/science.1109191. PMID 15905399. S2CID 46580799. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- Than, Ker (May 11, 2006). "Scientists Discover New Monkey Genus In Africa". LiveScience. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- Palmer, Brian (2012-06-03). "Yeti, licorne... les animaux fantastiques existent-ils vraiment?". Slate (in French). Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- "Newly Discovered Monkey Is Threatened with Extinction". Newswise. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Wallis, J.; Rylands, A.B.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Oates, J.F.; Williamson, E.A.; Palacios, E.; Heymann, E.W.; Kierulff, M.C.M.; Yongcheng, Long; Supriatna, J.; Roos, C.; Walker, S.; Cortés-Ortiz, L.; Schwitzer, C., eds. (2009). Primates in Peril: The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2008–2010 (PDF). Illustrated by S.D. Nash. Arlington, VA.: IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), and Conservation International (CI). pp. 1–92. ISBN 978-1-934151-34-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2014-02-20.