Choline transporter

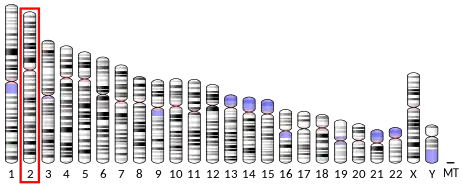

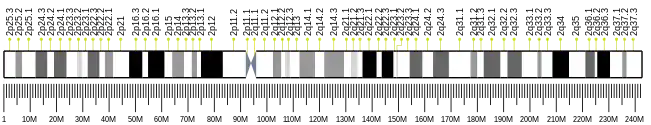

The high-affinity choline transporter (ChT) also known as solute carrier family 5 member 7 is a protein in humans that is encoded by the SLC5A7 gene.[5] It is a cell membrane transporter and carries choline into acetylcholine-synthesizing neurons.

| SLC5A7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | SLC5A7, CHT, CHT1, HMN7A, hCHT, Choline transporter, solute carrier family 5 member 7, CMS20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 608761 MGI: 1927126 HomoloGene: 32516 GeneCards: SLC5A7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hemicholinium-3 is an inhibitor of the ChT and can be used to deplete acetylcholine stores, while coluracetam is an enhancer of the ChT and can increase cholinergic neurotransmission by enhancing acetylcholine synthesis.

Function

Choline is a direct precursor of acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter of the central and peripheral nervous system that regulates a variety of autonomic, cognitive, and motor functions. SLC5A7 is a Na(+)- and Cl(-)- dependent high-affinity transporter that mediates the uptake of choline for acetylcholine synthesis in cholinergic neurons.[5][6]

Mutations in the SLC5A7 gene have been associated with Distal spinal muscular atrophy with vocal cord paralysis (distal hereditary motor neuropathy type 7A).[7]

The ChT seems to be a site of action of some β-neurotoxins found in snake venoms, which disrupt peripheral cholinergic transmission by interfering with presynaptic acetylcholine synthesis. It is hypothesized that these toxins irreversibly block the ChT.[8][9]

Model organisms

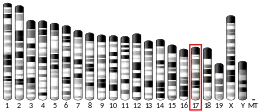

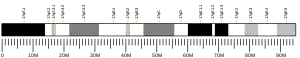

Model organisms have been used in the study of SLC5A7 function. A conditional knockout mouse line called Slc5a7tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi was generated at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.[10] Male and female animals underwent a standardized phenotypic screen[11] to determine the effects of deletion.[12][13][14][15] Additional screens performed: - In-depth immunological phenotyping[16]

Choline transporter in the human brain microvascular endothelial cells

Choline is a necessary reagent for the synthesis of acetylcholine in the central nervous system. Neurons get their choline by specific protein transporters known as choline transporters. In the human brain microvascular endothelial cells, two systems initiate the choline absorption. The first system is known as the Choline transporter-like protein 1, or CTL1. The second system is the Choline transporter-like protein 2, or CTL2. Those two systems are found on the plasma membrane of the brain microvascular endothelial cells. They are also found on the mitochondrial membrane. CTL2 was found to be highly expressed on the mitochondria. Meanwhile, CTL1 was mostly found on the plasma membrane of those microvascular cells.[17]

CTL2 is the main protein involved in the absorption of choline into the mitochondria for its oxidation, and CTL1 is the main protein for the choline uptake from the extracellular medium. CTL1 is a pH dependent protein. The absorption of choline through CTL1 proteins changes with the pH of the extracellular medium. When the pH of the medium is changed from 7.5 to 7.0-5.5, the rate of absorption of choline by CTL1 proteins decreases greatly. The choline uptake does not change upon the alkalinization of the extracellular medium. Moreover, it was found that the choline uptake is also influenced by the electronegativity of the plasma membrane. When the concentration of potassium ions is increased, the membrane becomes depolarized. The choline absorption decreases majorly as a result of the membrane depolarization by the potassium ions. The choline uptake was found to be only affected by the potassium ions. The sodium ions do not affect the affinity of CTL1 and CTL2 to choline.[17]

| Characteristic | Phenotype |

|---|---|

| All data available at.[11][16] | |

| Insulin | Normal |

| Homozygous viability at P14 | Abnormal |

| Recessive lethal study | Normal |

| Body weight | Normal |

| Neurological assessment | Normal |

| Grip strength | Normal |

| Dysmorphology | Normal |

| Indirect calorimetry | Normal |

| Glucose tolerance test | Normal |

| Auditory brainstem response | Normal |

| DEXA | Normal |

| Radiography | Normal |

| Eye morphology | Normal |

| Clinical chemistry | Normal |

| Haematology 16 Weeks | Normal |

| Peripheral blood leukocytes 16 Weeks | Normal |

| Salmonella infection | Normal |

See also

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000115665 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000023945 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Entrez Gene: Solute carrier family 5 (choline transporter), member 7".

- Apparsundaram S, Ferguson SM, George AL, Blakely RD (October 2000). "Molecular cloning of a human, hemicholinium-3-sensitive choline transporter". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 276 (3): 862–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3561. PMID 11027560.

- Barwick KE, Wright J, Al-Turki S, McEntagart MM, Nair A, Chioza B, Al-Memar A, Modarres H, Reilly MM, Dick KJ, Ruggiero AM, Blakely RD, Hurles ME, Crosby AH (December 2012). "Defective presynaptic choline transport underlies hereditary motor neuropathy". American Journal of Human Genetics. 91 (6): 1103–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.019. PMC 3516609. PMID 23141292.

- Dowdall MJ, Fohlman JP, Eaker D (October 1977). "Inhibition of high-affinity choline transport in peripheral cholinergic endings by presynaptic snake venom neurotoxins". Nature. 269 (5630): 700–2. Bibcode:1977Natur.269..700D. doi:10.1038/269700a0. PMID 593330. S2CID 4287430.

- Mollier P, Brochier G, Morot Gaudry-Talarmain Y (1990). "The action of notexin from tiger snake venom (Notechis scutatus scutatus) on acetylcholine release and compartmentation in synaptosomes from electric organ of Torpedo marmorata". Toxicon. 28 (9): 1039–52. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(90)90142-T. PMID 2260102.

- Gerdin AK (2010). "The Sanger Mouse Genetics Programme: high throughput characterisation of knockout mice". Acta Ophthalmologica. 88: 925–7. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.4142.x. S2CID 85911512.

- "International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium".

- Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V, Mujica AO, Thomas M, Harrow J, Cox T, Jackson D, Severin J, Biggs P, Fu J, Nefedov M, de Jong PJ, Stewart AF, Bradley A (June 2011). "A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function". Nature. 474 (7351): 337–42. doi:10.1038/nature10163. PMC 3572410. PMID 21677750.

- Dolgin E (June 2011). "Mouse library set to be knockout". Nature. 474 (7351): 262–3. doi:10.1038/474262a. PMID 21677718.

- Collins FS, Rossant J, Wurst W (January 2007). "A mouse for all reasons". Cell. 128 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.018. PMID 17218247. S2CID 18872015.

- White JK, Gerdin AK, Karp NA, Ryder E, Buljan M, Bussell JN, et al. (Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Project) (July 2013). "Genome-wide generation and systematic phenotyping of knockout mice reveals new roles for many genes". Cell. 154 (2): 452–64. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.022. PMC 3717207. PMID 23870131.

- "Infection and Immunity Immunophenotyping (3i) Consortium".

- Iwao B, Yara M, Hara N, Kawai Y, Yamanaka T, Nishihara H, Inoue T, Inazu M (February 2016). "Functional expression of choline transporter like-protein 1 (CTL1) and CTL2 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells". Neurochemistry International. 93: 40–50. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2015.12.011. PMID 26746385. S2CID 45392318.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.