Saltriovenator

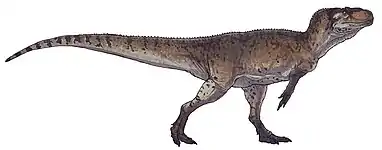

Saltriovenator (meaning "Saltrio hunter") is a genus of ceratosaurian dinosaur that lived during the Sinemurian stage of the Early Jurassic in what is now Italy. The type and only species is Saltriovenator zanellai; in the past, the species had been known under the informal name "saltriosaur". Although a full skeleton has not yet been discovered, Saltriovenator is thought to have been a large, bipedal carnivore similar to Ceratosaurus.

| Saltriovenator Temporal range: Early Sinemurian ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

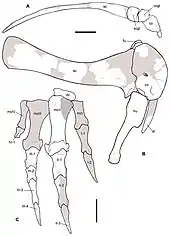

| Selected elements of the holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Ceratosauria |

| Genus: | †Saltriovenator Dal Sasso et al. 2018 |

| Species: | †S. zanellai |

| Binomial name | |

| †Saltriovenator zanellai Dal Sasso et al. 2018 | |

Discovery and naming

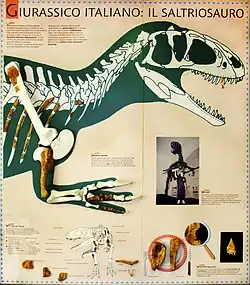

On 4 August 1996, the first remains of Saltriovenator were discovered by amateur paleontologist Angelo Zanella, searching for ammonites in the Salnova marble quarry in Saltrio, northern Italy. Zanella had already been working for the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano and this institution after being informed sent out a team to investigate the find. Cristiano Dal Sasso and the volunteers of the Paleontological Group of Besano, under the direction of Giorgio Teruzzi managed to salvage a number of chalk blocks visibly containing bones. The skeleton had shortly before its discovery been blown to pieces by explosives used in the quarry to break the marble layers. Blocks that had been secured were inserted into a bath of formic acid for 1,800 hours to free the bones.[1] Initially, 119 bone fragments were reported to have been collected in total;[2][3] this was later increased to 132. However, most cannot be exactly identified.[1]

In 2000, the museum opened a special exhibition of the bones. On this occasion, Dal Sasso provisionally gave the dinosaur, now thought to be a species new to science, the Italian name Saltriosauro. Although this has been occasionally Latinised to "Saltriosaurus", even in the scientific literature, in both the Italian and Latin form it remained an invalid nomen nudum.[1]

In December 2018, Dal Sasso, Simone Maganuco and Andrea Cau named and described the specimen as the type species Saltriovenator zanellai. The generic name combines a reference to Saltrio with Latin, venator, "hunter", a common suffix in the names of theropods. The authors pointed out that a venator is also a type of Roman gladiator. The specific name honours Zanella. Because the article was published in an electronic publication, Life Science Identifiers were necessary to make the name valid. These are 8C9F3B56-F622-4C39-8E8B-C2E890811E74 for the genus and BDD366A7-6A9D-4A32-9841-F7273D8CA00B for the species. Saltriovenator is the third dinosaur named from Italy, the first from the Alps and the second theropod from Italy, after Scipionyx.[1]

The holotype, MSNM V3664, was found in a layer of the Saltrio Formation dating from the earliest early Sinemurian, 199 million years old. It consists of a fragmentary skeleton with a lower jaw. About 10% of the skeleton has been discovered, including a tooth, a right splenial, a right prearticular, a neck rib, fragments of the dorsal ribs and scapulae, a well preserved but incomplete furcula, humeri, metacarpal II, phalanx II-1, phalanx III-1, phalanx III-2, manual ungual III, a distal tarsal III, a distal tarsal IV and the proximal second to fifth metatarsals. The holotype individual likely died on the shores of an ancient beach before being washed out to sea. After death, the skeletal remains suffered from prolonged transport, during which many bones were lost and the remaining ones highly fragmented.

Although Saltriovenator was not aquatic, the environment in which the carcass was deposited was likely pelagic, judging by the associated ammonites. The locality is also rich in crinoids, gastropods, bivalves, brachiopods and bryozoans.[4] Deposition occurred on a slope between a shallow carbonate platform and a deeper basin. Various scratches, grooves, and striations indicate that the carcass was subject to scavenging by marine invertebrates. The specimen represents a subadult individual, nearing its maximum size, of which the age has been estimated at twenty-four years.[1]

Description

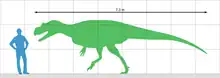

Because of the fragmentary nature of the remains, it was impossible to directly measure the size of the animal. The describing authors therefore compared the fossils with those of two theropods of a roughly similar volume. Comparing with the skeletal elements of MOR 693, an Allosaurus fragilis specimen, they conservatively concluded that the Saltriovenator holotype individual was at least seven to eight metres long. This would make Saltriovenator the largest known theropod living before the Aalenian stage, 25% longer than Ceratosaurus from the late Jurassic. Comparing with Ceratosaurus itself, resulted in a body length of 730 centimetres, a hip height of 220 centimetres and a skull length of eighty centimetres. The thighbone length would then have been about eighty to eighty-seven centimetres, which indicates a body weight of 1160 to 1524 kilogrammes. Another method consisted in extrapolating from the known length of the forelimb. Applying the usual limb ratio indicated a hindlimb length of 198 centimetres. The thighbone would then have been 822 to 887 millimetres long, indicating a weight of 1269 to 1622 kilogrammes.[1]

Classification

The precise systematic position of Saltriovenator has been traditionally uncertain, but it is known to be a theropod.[2][3] Dal Sasso originally referred it to the Tetanurae[5] He later considered that it may represent an allosauroid, although in either case it would predate other members of the clades by roughly 20-30 million years.[6] Benson considered it a member of Coelophysoidea in his review of Magnosaurus.[7][8] The presence of a wishbone[6] may support its placement as a tetanuran, although wishbones have been reported from coelophysoids.[9][10]

The 2018 description paper ran a large phylogenetic analysis, and found it to be a basal ceratosaur, the sister-taxon of Berberosaurus.[1] The phylogenetic analysis is as shown:

| Dinosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Provenance and Paleoenvironment

Saltriovenator was found on an open marine environment, where it was probably washed from the nearest mainland, being scavenged by invertebrates as proven by the presence of Sedilichnus sp. on the bones.[1] This depositional environment, part of the Saltrio Formation is considered as part of a proximal slope or ramp that was probably an open subtidal zone reached by the effects of storm waves and with constant bottom currents.[1] Since the beginning of the Jurassic, from Hettangian to earliest Sinemurian on the western Lombardy Basin there was a notorious continental area that was found to be wider than previously thought, where a warm humid paleoclimate developed.[11] The Dinosaur Fossils found on the Saltrio formation can have been translated from this area, or alternatively, the Arbostora swell (that was located at the north of the Saltrio formation, on Switzerland).[12] This was an emerged structural high close to the Saltrio Formation, that caused a division between two near subsiding basins located at Mt. Nudo (East) and Mt. Generoso (West).[12] It settled over a carbonate platform linked with other wider areas that appear along the west to the southeast, developing a large shallow water gulf to the north, where the strata deposited was controlled by a horst and tectonic gaben.[12] Several outcrops of the so-called "terra rossa" paleosoils were also found, including at Castello Cabiaglio-Orino, a dozen of kilometers West of Saltrio.[13][14] These outcrops show that the emerged areas that on the Hettangian-Sinemurian, the current location of the modern Maggiore Lake was covered with forests, what was proven by the presence of large plant fragments on the Moltrasio Formation.[11] The plants have been recovered between the locations of Cellina and Arolo (eastern side of Lake Maggiore), from rocks that have been found to be coeval in age to the Saltrio Formation.[4] The Flora includes genera such as Bennettitales (Ptilophyllum), terrestrial Araucariaceae (Pagiophyllum), and Cheirolepidiaceae (Brachyphyllum), that developed on inland areas with dry-warm conditions.[4] Saltriovenator probably come from this nearby landmass, as other emerged zones, such as the Trento Platform where it's far of the location of discovery. If so, this theropod was probably the largest predator on the region.[1]

See also

References

- Dal Sasso, C; Maganuco, S; Cau, A. (2018). "The oldest ceratosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda), from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds". PeerJ. 1 (1): e5976. doi:10.7717/peerj.5976. PMC 6304160. PMID 30588396. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- The Theropod Database

- Matthew T. Carrano, Roger B. J. Benson, Scott D. Sampson: The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Bd. 10, Nr. 2, 2012

- Lualdi, A. (1999). "New data on the Western part of the M. Nudo Basin (Lower Jurassic, West Lombardy)". Tübingen Geowissenschaftliche Arbeiten, Series A. 52 (1): 173–176.

- Dal Sasso, C. (2001). Dinosauri italiani (2 ed.). Venezia: Marsilio Editori. pp. 45–66.

- Dal Sasso, Cristiano (2003). "Dinosaurs of Italy". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (1): 45–66. doi:10.1016/S1631-0683(03)00007-1. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Benson, Roger B. J. (2010). "The osteology of Magnosaurus nethercombensis (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom and a re-examination of the oldest records of tetanurans". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (1): 131–146. doi:10.1080/14772011003603515. S2CID 140198723. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2003). The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs (= Special Papers in Palaeontology. Bd. 69) (PDF) (1 ed.). London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 1–213. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Rinehart, Larry F.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Hunt, Adrian P. (2007). "Furculae in the Late Triassic theropod dinosaur Coelophysis bauri" (PDF). Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 81 (2): 174–180. doi:10.1007/BF02988391. S2CID 129076419. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Tykoski, R. S.; Forster, C. A.; Rowe, T.; Sampson, S. D.; Munyikwa, D. (2002). "A furcula in the coelophysid theropod Syntarsus [Now Megapnosaurus]". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 728–733. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0728:AFITCT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 39088559. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Jadoul, Flavio; Galli, M. T.; Calabrese, Lorenzo; Gnaccolini, Mario (2005). "Stratigraphy of Rhaetian to Lower Sinemurian carbonate platforms in western Lombardy (Southern Alps, Italy): paleogeographic implications". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 111 (2): 285–303. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Kalin, O.; DM, T. (1977). "Sedimentation und Paläotektonik in den westlichen Südalpen: Zur triasisch-jurassischen Geschichte des Monte Nudo-Beckens". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 70 (2): 295. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Leuzinger, P. (1925). Geologische Beschreibung des Monte Campo dei Fiori u. der Sedimentzone Luganersee-Valcuvia. Russy, FR, Switzerland: Buchdruckerei Emil Birkhäuse.

- Wiedenmayer, F. (1963). Obere Trias bis mittlerer Lias zwischen Saltrio und Tremona (Lombardische Alpen). Die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Stratigraphie, Sedimentologie und syngenetischer Tektonik. Dissertation (1 ed.). Löbnitz: Basel, Birkhäuser.

.jpg.webp)