Swiss German

Swiss German (Standard German: Schweizerdeutsch, Alemannic German: Schwiizerdütsch, Schwyzerdütsch, Schwiizertüütsch, Schwizertitsch Mundart,[note 1] and others) is any of the Alemannic dialects spoken in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and in some Alpine communities in Northern Italy bordering Switzerland. Occasionally, the Alemannic dialects spoken in other countries are grouped together with Swiss German as well, especially the dialects of Liechtenstein and Austrian Vorarlberg, which are closely associated to Switzerland's.[4][5]

| Swiss German | |

|---|---|

| Schwiizerdütsch | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈʃʋitsərˌd̥ytʃ] |

| Native to | Switzerland (as German), Liechtenstein, Vorarlberg (Austria), Piedmont & Aosta Valley (Italy) |

Native speakers | 4.93 million in Switzerland (2013)[1] Unknown number in Germany and Austria |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | gsw |

| ISO 639-3 | gsw (with Alsatian) |

| Glottolog | swis1247wals1238 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-f (45 varieties: 52-ACB-faa to -fkb) |

| IETF | gsw[2] |

Swiss German is classified as Potentially Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger[3] | |

Linguistically, Alemannic is divided into Low, High and Highest Alemannic, varieties all of which are spoken both inside and outside Switzerland. The only exception within German-speaking Switzerland is the municipality of Samnaun, where a Bavarian dialect is spoken. The reason Swiss German dialects constitute a special group is their almost unrestricted use as a spoken language in practically all situations of daily life, whereas the use of the Alemannic dialects in other countries is restricted or even endangered.[6]

The dialects that comprise Swiss German must not be confused with Swiss Standard German, the variety of Standard German used in Switzerland. Swiss Standard German is fully understandable to all speakers of Standard German, while many people in Germany – especially in the north – do not understand Swiss German. An interview with a Swiss German speaker, when shown on television in Germany, will require subtitles.[7] Although Swiss German is the native language in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, Swiss school students are taught Swiss Standard German from the age of six. They are thus capable of understanding, writing and speaking Standard German, with varying abilities mainly based on their level of education.

Use

Unlike most regional languages in modern Europe, Swiss German is the everyday spoken language for the majority of the population, in all social strata, from urban centers to the countryside. Using Swiss German conveys neither social nor educational inferiority and is done with pride[8] There are a few settings where speaking Standard German is demanded or polite, e.g., in education (but not during breaks in school lessons, where the teachers will speak with students in Swiss German), in multilingual parliaments (the federal parliaments and a few cantonal and municipal ones), in the main news broadcast or in the presence of non-Alemannic speakers. This situation has been called a "medial diglossia", since the spoken language is mainly Swiss German, whereas the written language is mainly (the Swiss variety of) Standard German.

In 2014, about 87% of the people living in the German-speaking portion of Switzerland were using Swiss German in their everyday lives.[9]

Swiss German is intelligible to speakers of other Alemannic dialects, but largely unintelligible to speakers of Standard German who lack adequate prior exposure. This is also a challenge for French- or Italian-speaking Swiss who learn Standard German at school. In the rare cases that Swiss German is heard on TV in Germany and Austria, the speaker is most likely to be dubbed or subtitled. More commonly, a Swiss speaker will speak Standard German on non-Swiss media.

"Dialect rock" is a music genre using the language; many Swiss rock bands, however, sing in English instead.

The Swiss Amish of Adams County, Indiana, and their daughter settlements also use a form of Swiss German.[10]

Variation and distribution

Swiss German is a regional or political umbrella term, not a linguistic unity. For all Swiss-German dialects, there are idioms spoken outside Switzerland that are more closely related to them than to some other Swiss-German dialects. The main linguistic divisions within Swiss German are those of Low, High and Highest Alemannic, and mutual intelligibility across those groups is almost fully seamless, despite some differences in vocabulary. Low Alemannic is only spoken in the northernmost parts of Switzerland, in Basel and around Lake Constance. High Alemannic is spoken in most of the Swiss Plateau, and is divided into an eastern and a western group. Highest Alemannic is spoken in the Alps.

- Low Alemannic:

- Basel German in Basel-Stadt (BS), closely related to Alsatian

- High Alemannic:

- Western:

- Bernese German, in the Swiss Plateau parts of Bern (BE)

- Dialects of Basel-Landschaft (BL)

- Dialects of Solothurn (SO)

- Dialects of the western part of Aargau (AG)

- In a middle position between eastern and western:

- Dialects in the eastern part of Aargau (AG)

- Dialects of Lucerne (LU)

- Dialects of Zug (ZG)

- Zürich German, in Zürich (ZH)

- Eastern:

- Dialects of St. Gallen (SG)

- Dialects of Appenzell (AR & AI)

- Dialects of Thurgau (TG)

- Dialects of Schaffhausen (SH)

- Dialects in parts of Graubünden (GR)

- Western:

- Highest Alemannic:

- Dialects in parts of Canton of Fribourg (FR)

- Dialects of the Bernese Oberland (BE)

- Dialects of Unterwalden (OW & NW) and Uri (UR)

- Dialects of Schwyz (SZ)

- Dialects of Glarus (GL)

- Walliser German in parts of the Valais (VS)

- Walser German: due to the medieval migration of the Walser, Highest Alemannic spread to pockets of what are now parts of northern Italy (Piedmont), the north-west of Ticino (TI), parts of Graubünden (GR), Liechtenstein and Vorarlberg.

One can separate each dialect into numerous local subdialects, sometimes down to a resolution of individual villages. Speaking the dialect is an important part of regional, cantonal and national identities. In the more urban areas of the Swiss plateau, regional differences are fading due to increasing mobility and to a growing population of non-Alemannic background. Despite the varied dialects, the Swiss can still understand one another, but may particularly have trouble understanding Walliser dialects.

History

Most Swiss German dialects, being High German dialects, have completed the High German consonant shift (synonyms: Second Germanic consonant shift, High German sound shift[11][12]), that is, they have not only changed t to [t͡s] or [s] and p to [p͡f] or [f], but also k to [k͡x] or [x]. There are, however, exceptions, namely the idioms of Chur and Basel. Basel German is a Low Alemannic dialect (mostly spoken in Germany near the Swiss border), and Chur German is basically High Alemannic without initial [x] or [k͡x].

Examples:

| High Alemannic | Low Alemannic | Standard German | Spelling | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ˈxaʃtə] | [ˈkʰaʃtə] | [ˈkastn] | 'Kasten' | 'box' |

| [k͡xaˈri(ː)b̥ik͡x] | [kʰaˈriːbikʰ] | [kaˈriːbɪk] | 'Karibik' | 'Caribbean' |

The High German consonant shift happened between the 4th and 9th centuries south of the Benrath line, separating High German from Low German, where high refers to the geographically higher regions of the German-speaking area of those days (combining Upper German and Central German varieties - also referring to their geographical locations). North of the Benrath line up to the North Sea, this consonant shift did not happen.

The Walser migration, which took place between the 12th and 13th centuries, spread upper Wallis varieties towards the east and south, into Grisons and even further to western Austria and northern Italy. Informally, a distinction is made between the German-speaking people living in the canton of Valais, the Walliser, and the migrated ones, the Walsers (to be found mainly in Graubünden, Vorarlberg in Western Austria, Ticino in South Switzerland, south of the Monte Rosa mountain chain in Italy (e.g. in Issime in the Aosta valley), Tirol in North Italy, and Allgäu in Bavaria).

Generally, the Walser communities were situated on higher alpine regions, so were able to stay independent of the reigning forces of those days, who did not or were not able to follow and monitor them all the time necessary at these hostile and hard to survive areas. So, the Walser were pioneers of the liberalization from serfdom and feudalism. And, Walser villages are easily distinguishable from Grisonian ones, since Walser houses are made of wood instead of stone.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m – mː | n – nː | ŋ | ||

| Stop | b̥ – p | d̥ – t | ɡ̊ – k | ||

| Affricate | p͡f | t͡s | t͡ʃ | k͡x | |

| Fricative | v̥ – f | z̥ – s | ʒ̊ – ʃ | ɣ̊ – x | h |

| Approximant | ʋ | l – lː | j | ||

| Rhotic | r |

Like most other Southern German dialects, Swiss German dialects have no voiced obstruents. The voiceless lenis obstruents are often marked with the IPA diacritic for voicelessness as /b̥ d̥ ɡ̊ v̥ z̥ ɣ̊ ʒ̊/.[13] Swiss German /p, t, k/ are not aspirated. Nonetheless, there is an opposition of consonant pairs such as [t] and [d] or [p] and [b]. Traditionally, it has been described as a distinction of fortis and lenis in the original sense, that is, distinguished by articulatory strength or tenseness.[14] Alternatively , it has been claimed to be a distinction of quantity.[15]

Aspirated [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ] have secondarily developed by combinations of prefixes with word-initial /h/ or by borrowings from other languages (mainly Standard German): /ˈphaltə/ 'keep' (standard German behalten [bəˈhaltn̩]); /ˈtheː/ 'tea' (standard German Tee [ˈtʰeː]); /ˈkhalt/ 'salary' (standard German Gehalt [ɡəˈhalt]). In the dialects of Basel and Chur, aspirated /kʰ/ is also present in native words, corresponding to the affricate /kx/ of the other dialects, which does not occur in Basel or Chur.

Swiss German keeps the fortis–lenis opposition at the end of words. There can be minimal pairs such as graad [ɡ̊raːd̥] 'straight' and Graat [ɡ̊raːt] 'arête' or bis [b̥ɪz̥] 'be (imp.)' and Biss [b̥ɪs] 'bite'. That distinguishes Swiss German and Swiss Standard German from German Standard German, which neutralizes the fortis–lenis opposition at the ends of words. The phenomenon is usually called final-obstruent devoicing even though, in the case of German, phonetic voice may not be involved.

Unlike Standard German, Swiss German /x/ does not have the allophone [ç] but is typically [x], with allophones [ʁ̥ – χ]. The typical Swiss shibboleth features this sound: Chuchichäschtli ('kitchen cupboard'), pronounced [ˈχuχːiˌχæʃtli].

Most Swiss German dialects have gone through the Alemannic n-apocope, which has led to the loss of final -n in words such as Garte 'garden' (standard German Garten) or mache 'to make' (standard German machen). In some Highest Alemannic dialects, the n-apocope has also been effective in consonant clusters, for instance in Hore 'horn' (High Alemannic Horn) or däiche 'to think' (High Alemannic dänke). Only the Highest Alemannic dialects of the Lötschental and of the Haslital have preserved the -n.

The phoneme /r/ is pronounced as an alveolar trill [r] in many dialects, but some dialects, especially in the Northeast or in the Basel region, have a uvular trill [ʀ], and other allophones resulting in fricatives and an approximant as [ʁ ʁ̥ ʁ̞] like in many German varieties of Germany.

In many varieties of Bernese German and adjacent dialects, an /l/ at the syllable coda and intervicalic /lː/ are pronounced as a [w] or [wː] respectively.

A labiodental approximant [ʋ] is used instead of the Northern Standard German fricative [v] as the reflex of Middle High German /w/. In Walser German, the fricative is used instead.[16]

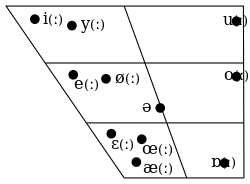

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i | y | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʏ | ʊ | |

| Close-mid | e | ø | ə | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | œ | (ɔ) | |

| Open | æ | (a) | ɒ ~ ɑ | |

Most Swiss German dialects have rounded front vowels, unlike other High German dialects.[17] Only in Low Alemannic dialects of northwestern Switzerland (mainly Basel) and in Walliser dialects have rounded front vowels been unrounded. In Basel, rounding is being reintroduced because of the influence of other Swiss German dialects.

Like Bavarian dialects, Swiss German dialects have preserved the opening diphthongs of Middle High German: /iə̯, uə̯, yə̯/: in /liə̯b̥/ 'lovely' (standard German lieb but pronounced /liːp/); /huə̯t/ 'hat' (standard German Hut /huːt/); /xyə̯l/ 'cool' (Standard German kühl /kyːl/). Some diphthongs have become unrounded in several dialects. In the Zürich dialect, short pronunciations of /i y u/ are realized as [ɪ ʏ ʊ]. Sounds like the monophthong [ɒ] can frequently become unrounded to [ɑ] among many speakers of the Zürich dialect. Vowels such as a centralized [a] and an open-mid [ɔ] only occur in the Bernese dialect.[18]

Like in Low German, most Swiss German dialects have preserved the old West-Germanic monophthongs /iː, uː, yː/: /pfiːl/ 'arrow' (Standard German Pfeil /pfaɪ̯l/); /b̥uːx/ 'belly' (Standard German Bauch /baʊ̯x/); /z̥yːlə/ 'pillar' (Standard German Säule /zɔʏ̯lə/). A few Alpine dialects show diphthongization, like in Standard German, especially some dialects of Unterwalden and Schanfigg (Graubünden) and the dialect of Issime (Piedmont).

| Middle High German/many Swiss German dialects | Unterwalden dialect | Schanfigg and Issime dialects | Standard German | translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [huːs] | [huis] | [hous] | [haʊ̯s] | 'house' |

| [tsiːt] | [tseit] | [tseit] | [tsaɪ̯t] | 'time' |

Some Western Swiss German dialects like Bernese German have preserved the old diphthongs /ei̯, ou̯/, but the other dialects have /ai̯, au̯/ like Standard German or /æi̯, æu̯/. Zürich German, and some other dialects distinguish primary diphthongs from secondary ones that arose in hiatus: Zürich German /ai̯, au̯/ from Middle High German /ei̯, ou̯/ versus Zürich German /ei̯, ou̯/ from Middle High German /iː, uː/; Zürich German /bai̯, frau̯/ 'leg, woman' from Middle High German bein, vrouwe versus Zürich German /frei̯, bou̯/ 'free, building' from Middle High German frī, būw.

Suprasegmentals

In many Swiss German dialects, consonant length and vowel length are independent from each other, unlike other modern Germanic languages. Here are examples from Bernese German:

| short /a/ | long /aː/ | |

|---|---|---|

| short /f/ | /hafə/ 'bowl' | /d̥i b̥raːfə/ 'the honest ones' |

| long /fː/ | /afːə/ 'apes' | /ʃlaːfːə/ 'to sleep' |

Lexical stress is more often on the first syllable than in Standard German, even in French loans like [ˈmɛrsːi] or [ˈmersːi] 'thanks' (despite stress falling on the final syllable in French). However, there are many different stress patterns, even within dialects. Bernese German has many words that are stressed on the first syllable: [ˈkaz̥inɔ] 'casino' while Standard German has [kʰaˈziːno]. However, no Swiss German dialect is as consistent as Icelandic in that respect.

Grammar

The grammar of Swiss dialects has some idiosyncratic features in comparison to Standard German:

- There is no preterite indicative (yet there is a preterite subjunctive).

- The preterite is replaced by perfect constructs (this also happens in spoken Standard German, particularly in Southern Germany and Austria).

- It is still possible to form pluperfect phrases, by applying the perfect construct twice to the same sentence.

- There is no genitive case, though certain dialects have preserved a possessive genitive (for instance in rural Bernese German). The genitive case is replaced by two constructions: The first of these is often acceptable in Standard German as well: possession + Prp. vo (Std. German von) + possessor: es Buech vomene Profässer vs. Standard German ein Buch von einem Professor ('a book of a professor'), s Buech vom Profässer vs. Standard German das Buch des Professors ('the professor's book'). The second is still frowned on where it appears in Standard German (from dialects and spoken language): dative of the possessor + the possessive pronoun referring to the possessor + possession: em Profässer sis Buech ('the professor his book').[19]

- The order within verb groups may vary, e.g. wo du bisch cho/wo du cho bisch vs. Standard German als du gekommen bist 'when you have come/came'.[20] In fact, dependencies can be arbitrarily cross-serial, making Swiss German one of the few known non-context-free natural languages.[21]

- All relative clauses are introduced by the relative particle wo ('where'), never by the relative pronouns der, die, das, welcher, welches as in Standard German, e.g. ds Bispil, wo si schrybt vs. Standard German das Beispiel, das sie schreibt ('the example that she writes'); ds Bispil, wo si dra dänkt vs. Standard German das Beispiel, woran sie denkt ('the example that she thinks of'). Whereas the relative particle wo replaces the Standard German relative pronouns in the Nom. (subject) and Acc. (direct object) without further complications, in phrases where wo plays the role of an indirect object, a prepositional object, a possessor or an adverbial adjunct it has to be taken up later in the relative clause by reference of (prp. +) the personal pronoun (if wo refers to a person) or the pronominal adverb (if wo refers to a thing). E.g. de Profässer won i der s Buech von em zeiget ha ('the professor whose book I showed you'), de Bärg wo mer druf obe gsii sind ('the mountain that we were upon').[19]

Overview

In Swiss German, a small number of verbs reduplicate in a reduced infinitival form, i.e. unstressed shorter form, when used in their finite form governing the infinitive of another verb. The reduced and reduplicated part of the verb in question is normally put in front of the infinitive of the second verb.[22] This is the case for the motion verbs gaa 'to go' and choo 'to come' when used in the meaning of 'go (to) do something', 'come (to) do something', as well as the verbs laa 'to let' and in certain dialects afaa 'to start, to begin' when used in the meaning of 'let do something', or 'start doing something'.[23] Most affected by this phenomenon is the verb gaa, followed by choo. Both laa and afaa are less affected and only when used in present tense declarative main clauses.[24]

Declarative sentence examples:

| Swiss German | Ich | gang | jetzt | go | ässe |

| Gloss | I | go-1SG | now | go | eat-INF |

| Standard German | Ich | gehe | jetzt | Ø | essen |

| English | I'm going to eat now. / I'll go eat now. | ||||

| Swiss German | Er | chunnt | jetzt | cho | ässe |

| Gloss | He | comes | now | come | eat-INF |

| Standard German | Er | kommt | jetzt | Ø | essen |

| English | He's coming to eat now. | ||||

| Swiss German | Du | lahsch | mi | la | ässe |

| Gloss | You | let-2SG | me-ACC | let | eat-INF |

| Standard German | Du | lässt | mich | Ø | essen |

| English | You're letting me eat. / You let me eat. | ||||

| Swiss German | Mier | fanged | jetzt | a | fa | ässe |

| Gloss | We | start-1PL | now | start-PREF | start | eat-INF |

| Standard German | Wir | fangen | jetzt | an | zu | essen |

| English | We're starting to eat now. / We start eating now. | |||||

As the examples show, all verbs are reduplicated with a reduced infinitival form when used in a declarative main clause. This is especially interesting as it stands in contrast to the standard variety of German and other varieties of the same, where such doubling effects are not found as outlined in the examples.[25]

Afaa: weakest doubling effects

Reduplication effects are weaker in the verbs laa 'to let' and afaa 'to start, to begin' than they are in gaa 'to go' and choo 'to come'. This means that afaa is most likely to be used without its reduplicated and reduced form while retaining grammaticality, whereas utterances with goo are least likely to remain grammatical without the reduplicated part.

Between laa and afaa, these effects are weakest in afaa. This means that while reduplication is mandatory for laa in declarative main clauses almost everywhere in the country, this is the case for fewer varieties of Swiss German with afaa.[26] The reason for this is unknown, but it has been hypothesized that the fact that afaa has a separable prefix (a-) might weaken its doubling capacity.[26] The presence of this separable prefix also makes the boundaries between the reduced infinitival reduplication form and the prefix hard if not impossible to determine.[26] Thus, in the example above for afaa, an argument could be made that the prefix a- is left off, while the full reduplicated form is used:

| Swiss German | Mier | fanged | jetzt | afa | ässe |

| Gloss | We | start-1PL | now | start | eat-INF |

| English | We're starting to eat now. / We start eating now. | ||||

In this case, the prefix would be omitted, which is normally not permissible for separable prefixes, and in its place, the reduplication form is used.

Meanwhile, afaa is not reduplicated when used in a subordinate clause or in the past tense. In such instances, doubling would result in ungrammaticality:

Past tense example with afaa:

| Swiss German | Sie | händ | aagfange | *afa | ässe |

| Gloss | They | have-3PL | started-PTCP | *start | eat-INF |

| English | They started to eat. | ||||

The same is true for subordinate clauses and the verb afaa:

Subordinate clause examples with afaa:

| Swiss German | Ich | weiss | dass | sie | jetzt | afaat | *afa | ässe |

| Gloss | I | know-1SG | that | she | now | starts | *start | eat-INF |

| English | I know that she's starting to eat now. / I know that she starts eating now. | |||||||

In order to achieve grammaticality in both instances, the reduced doubling part afa would have to be taken out.

Laa and optionality of reduplication

While afaa 'to start, to begin' is quite restricted when it comes to reduplication effects, the phenomenon is more permissive, but not mandatory in the verb laa 'to let'. While present tense declarative sentences are generally ungrammatical when laa remains unduplicated, this is not true for past tense and subordinate clauses, where doubling effects are optional at best:

Past tense example with laa:

| Swiss German | Er | het | mi | la | ässe | (laa) |

| Gloss | He | has | me-ACC | let | eat-INF | (let-PTCP) |

| English | He has let me eat. / He let me eat. | |||||

Subordinate clause example with laa:

| Swiss German | Ich | weiss | dass | er | mi | laat | (la) | ässe |

| Gloss | I | know-1SG | that | he | me-ACC | lets | (let) | eat-INF |

| English | I know that he lets me eat. / I know that he's letting me eat. | |||||||

In the use of this form, there are both geographical and age differences. Reduplication is found more often in the western part of Switzerland than in the eastern part, while younger generations are much more inclined to leave out reduplication, which means that the phenomenon is more widespread in older generations.[27]

Gaa and choo: stronger reduplication

Ungrammaticality in reduplication of afaa 'to start, to begin' in the past tense and in subordinate clauses as well as the somewhat more lenient use of reduplication with laa 'to let' stand in contrast to doubling effects of the motion verbs gaa 'to go' and choo 'to come'. When the latter two verbs are used in other utterances other than a declarative main clause, where the finite verb traditionally is in second position, their use might not be mandatory; however, it is correct and grammatical to double them both in the past tense and in subordinate clauses:

Past tense example with gaa and choo:

| Swiss German | Er | isch | go | ässe | (g'gange) |

| Gloss | He | is | go | eat-INF | (gone) |

| English | He has gone to eat. / He went to eat. | ||||

| Swiss German | Sie | isch | cho | ässe | (cho) |

| Gloss | She | is | come | eat-INF | (come-PTCP) |

| English | She has come to eat. / She came to eat. | ||||

As outlined in both examples, the reduplicated form of both gaa and choo can but does not have to be used in order for the past tense sentences to be grammatical.Notably, it is the reduced form of both verbs that is necessary, not the full participle form.

Subordinate clause examples for gaa and choo:

| Swiss German | Ich | weiss | dass | sie | gaat | go | ässe |

| Gloss | I | know-1SG | that | she | goes | go | eat-INF |

| English | I know that she'll go eat. / I know that she's going to eat. | ||||||

| Swiss German | Ich | weiss | dass | sie | chunnt | cho | ässe |

| Gloss | I | know-1SG | that | she | comes | come | eat-INF |

| English | I know that she'll come to eat. / I know that she's coming to eat. | ||||||

In subordinate clauses, the reduplicated part is needed as the sentence would otherwise be ungrammatical in both gaa and choo.[28]

The same is true for the past tense. Since there is only one past tense in Swiss German and since this is formed using an auxiliary verb – sii 'to be' or haa 'to have', depending on the main verb – reduplication seems to be affected and therefore, less strictly enforced for gaa and choo, while it is completely ungrammatical for afaa and optional for laa respectively.

Questions

Questions behave a lot like their declarative counterparts, and reduplication is therefore mandatory for both motion verbs gaa 'to go' and choo 'to come', while laa 'to let' and afaa 'to start, to begin' show weaker doubling effects and more optionality. Furthermore, this is the case for both open and close (yes/no) questions. Consider the following examples:

Afaa in open and close questions:

| Swiss German | Fangt | er | a | (fa) | ässe |

| Gloss | Starts | he | start-PREF | (start) | eat-INF |

| English | Does he start eating? / Is he starting to eat? | ||||

| Swiss German | Wenn | fangt | er | a | (fa) | ässe |

| Gloss | When | starts | he | start-PREF | (start) | eat-INF |

| English | When does he start eating? / When is he starting to eat? | |||||

Just like in declarative forms, afaa could be reduced to a- and thus be considered the detachable prefix. In this case, afaa would no longer be a reduplicated verb, and that is where the language development seems to move towards.[26]

Laa in open and close questions:

| Swiss German | Laat | er | sie | (la) | ässe |

| Gloss | Lets | he | her-ACC | (let) | eat-INF |

| English | Does he let her eat? / Is he letting her eat? | ||||

| Swiss German | Wenn | laat | er | sie | (la) | ässe |

| Gloss | When | lets | he | her-ACC | (let) | eat-INF |

| English | When does he let her eat? / When is he letting her eat? | |||||

Choo and especially gaa, however, do not allow for their reduced doubling part to be left out in questions, irrespective of the fact whether they are open or close:

Choo in open and close questions:

| Swiss German | Chunnt | er | cho | ässe |

| Gloss | Comes | he | come | eat-INF |

| English | Does he come to eat? / Is he coming to eat? | |||

| Swiss German | Wenn | chunnt | er | cho | ässe |

| Gloss | When | come | he | come | eat-INF |

| English | When does he come to eat? / When is he coming to eat? | ||||

Gaa in open and close questions:

| Swiss German | Gaat | er | go | ässe |

| Gloss | Goes | he | go | eat-INF |

| English | Does he go eat? / Is he going to eat? | |||

| Swiss German | Wenn | gaat | er | go | ässe |

| Gloss | When | goes | he | go | eat-INF |

| English | When does he go eat? / When is he going to eat? | ||||

Imperative mood

In the imperative mood, just like in questions, gaa 'to go' and choo 'come' are very strict in their demand for doubling. The same is true for laa 'to let'; it is ungrammatical to use it in imperative mood undoubled. On the other hand, afaa leaves a lot more room for the speaker to play with. Speakers accept both sentences with only the detachable prefix and no doubling, and sentences with the full doubled form.

Imperative mood: gaa

| Swiss German | Gang | go | ässe |

| Gloss | Go-2SG.IMP | go | eat-INF |

| English | Go eat! | ||

Imperative mood: choo

| Swiss German | Chum | cho | ässe |

| Gloss | Come-2SG.IMP | come | eat-INF |

| English | Come eat! | ||

Imperative mood: laa

| Swiss German | Laa | mi | la | ässe |

| Gloss | Let-2SG.IMP | me-ACC | let | eat-INF |

| English | Let me eat! | |||

Imperative mood: afaa

| Swiss German | Fang | a | ässe |

| Gloss | Start-2SG.IMP | start-PREF | eat-INF |

| Swiss German | Fang | afa | ässe |

| Gloss | Start-2SG.IMP | start | eat-INF |

| English | Start eating! | ||

Cross-doubling with choo and gaa

In the case of the verb choo 'to come', there are situations when instead of it being reduplicated with its reduced form cho, the doubled short form of gaa 'to go', go, is used instead. This is possible in almost all instances of choo, regardless of mood or tense.[28][29] The examples below outline choo reduplicated with both its reduced form cho and the reduced form of gaa, go, in different sentence forms.

Declarative main clause, present tense

| Swiss German | Er | chunnt | cho/go | ässe |

| Gloss | He | comes | come/go | eat-INF |

| English | He comes to eat. / He's coming to eat. | |||

Declarative main clause past tense

| Swiss German | Er | isch | cho/go | ässe | cho |

| Gloss | He | is | come/go | eat-INF | come-PTCP |

| English | He came to eat. / He has come to eat. | ||||

Subordinate clause

| Swiss German | Ich | weiss | dass | er | chunnt | cho/go | ässe |

| Gloss | I | know-1SG | that | he | comes | come/go | eat-INF |

| English | I know that he's coming to eat. / I know that he comes to eat. | ||||||

Imperative mood

| Swiss German | Chum | cho/go | ässe |

| Gloss | Come-2SG.IMP | come/go | eat-INF |

| English | Come eat! | ||

Multiple reduplication with gaa and choo

With the motion verbs gaa 'to go' and choo 'to come', where reduplication effects are strongest, there is some variation regarding their reduplicated or reduced forms. Thus, in some Swiss German dialects, gaa will be doubled as goge, while choo will be doubled as choge. In some analyses, this is described as a multiple reduplication phenomenon in that the reduced infinitives go or cho part is repeated as ge, providing the forms goge and choge.[30] However, these forms are used less frequently than their shorter counterparts and seem to be concentrated into a small geographic area of Switzerland.

Vocabulary

The vocabulary is varied, especially in rural areas: many specialized terms have been retained, e.g., regarding cattle or weather. In the cities, much of the rural vocabulary has been lost. A Swiss German greeting is Grüezi, from Gott grüez-i (Standard German Gott grüsse Euch), loosely meaning 'God bless you'.[31][32]

Most word adoptions come from Standard German. Many of these are now so common that they have totally replaced the original Swiss German words, e.g. the words Hügel 'hill' (instead of Egg, Bühl), Lippe 'lip' (instead of Lëfzge). Others have replaced the original words only in parts of Switzerland, e.g., Butter 'butter' (originally called Anke in most of Switzerland). Virtually any Swiss Standard German word can be borrowed into Swiss German, always adapted to Swiss German phonology. However, certain Standard German words are never used in Swiss German, for instance Frühstück 'breakfast', niedlich 'cute' or zu hause 'at home'; instead, the native words Zmorge, härzig and dehei are used.

Swiss dialects have quite a few words from French and Italian, which are perfectly assimilated. Glace (ice cream) for example is pronounced /ɡlas/ in French but [ˈɡ̊lasːeː] or [ˈɡ̊lasːə] in many Swiss German dialects. The French word for 'thank you', merci, is also used as in merci vilmal (lit. 'thanks many times', cf. Standard German's danke vielmals and vielen Dank). Possibly, these words are not direct adoptions from French but survivors of the once more numerous French loanwords in Standard German, many of which have fallen out of use in Germany.

In recent years, Swiss dialects have also taken some English words which already sound very Swiss, e.g., [ˈfuːd̥ə] ('to eat', from 'food'), [ɡ̊ei̯mə] ('to play computer games', from game) or [ˈz̥nœːb̥ə] or [ˈb̥oːrd̥ə] – ('to snowboard', from snowboard). These words are probably not direct loanwords from English but have been adopted through standard German intermediation. While most of those loanwords are of recent origin, some have been in use for decades, e.g. [ˈ(t)ʃutːə] ('to play football', from shoot).

There are also a few English words which are modern adoptions from Swiss German. The dishes müesli, and rösti have become English words, as did loess (fine grain), flysch (sandstone formation), kepi, landammann, kilch, schiffli, and putsch in a political sense. The term bivouac is sometimes explained as originating from Swiss German,[33] while printed etymological dictionaries (e.g. the German Kluge or Knaurs Etymological Dictionary) derive it from Low German instead.

Orthography

History

Written forms that were mostly based on the local Alemannic varieties, thus similar to Middle High German, were only gradually replaced by the forms of New High German. This replacement took from the 15th to 18th centuries to complete. In the 16th century, the Alemannic forms of writing were considered the original, truly Swiss forms, whereas the New High German forms were perceived as foreign innovations. The innovations were brought about by the printing press and were also associated with Lutheranism. An example of the language shift is the Froschauer Bible: Its first impressions after 1524 were largely written in an Alemannic language, but since 1527, the New High German forms were gradually adopted. The Alemannic forms were longest preserved in the chancelleries, with the chancellery of Bern being the last to adopt New High German in the second half of the 18th century.[34][35][36]

Today all formal writing, newspapers, books and much informal writing is done in Swiss Standard German, which is usually called Schriftdeutsch (written German). Certain dialectal words are accepted regionalisms in Swiss Standard German and are also sanctioned by the Duden, e.g., Zvieri (afternoon snack). Swiss Standard German is virtually identical to Standard German as used in Germany, with most differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and orthography. For example, Swiss Standard German always uses a double s (ss) instead of the eszett (ß).

There are no official rules of Swiss German orthography. The orthographies used in the Swiss-German literature can be roughly divided into two systems: Those that try to stay as close to standard German spelling as possible and those that try to represent the sounds as well as possible. The so-called Schwyzertütschi Dialäktschrift was developed by Eugen Dieth, but knowledge of these guidelines is limited mostly to language experts. Furthermore, the spellings originally proposed by Dieth included some special signs not found on a normal keyboard, such as ⟨ʃ⟩ instead of ⟨sch⟩ for [ʃ] or ⟨ǜ⟩ instead of ⟨ü⟩ for [ʏ]. In 1986, a revised version of the Dieth-Schreibung was published, designed to be typed with a regular typewriter.[37]

Conventions

A few letters are used differently from the Standard German rules:

- ⟨k⟩ (and ⟨ck⟩) are used for the affricate /kx/.

- ⟨gg⟩ is used for the unaspirated fortis /k/.

- ⟨y⟩ (and sometimes ⟨yy⟩) traditionally stands for the /iː/ (in many dialects shortened to /i/, but still with closed quality) that corresponds to Standard German /aɪ̯/, e.g. in Rys 'rice' (standard German Reis /raɪ̯s/) vs. Ris 'giant' (standard German Riese /riːzə/). This usage goes back to an old ij-ligature. Many writers, however, do not use ⟨y⟩, but ⟨i⟩/⟨ii⟩, especially in the dialects that have lost distinction between these sounds, compare Zürich German Riis /riːz̥/ 'rice' or 'giant' to Bernese German Rys /riːz̥/ 'rice' vs. Ris /rɪːz̥/ ('giant'). Some use even ⟨ie⟩, influenced by Standard German spelling, which leads to confusion with ⟨ie⟩ for /iə̯/.

- ⟨w⟩ represents [ʋ], slightly different from Standard German as [v].

- ⟨ä⟩ usually represents [æ], and can also represent [ə] or [ɛ].

- ⟨ph⟩ represents [pʰ], ⟨th⟩ represents [tʰ], and ⟨gh⟩ represents [kʰ].

- Since [ei] is written as ⟨ei⟩, [ai] is written as ⟨äi⟩, though in eastern Switzerland ⟨ei⟩ is often used for both of these phonemes.

Literature

Since the 19th century, a considerable body of Swiss German literature has accumulated. The earliest works were in Lucerne German (Jost Bernhard Häfliger, Josef Felix Ineichen), in Bernese German (Gottlieb Jakob Kuhn), in Glarus German (Cosimus Freuler) and in Zürich German (Johann Martin Usteri, Jakob Stutz); the works of Jeremias Gotthelf which were published at the same time are in Swiss Standard German, but use many expressions of Bernese German. Some of the more important dialect writing authors and their works are:

- Anna Maria Bacher (born 1947), Z Kschpel fam Tzit; Litteri un Schattä; Z Tzit fam Schnee (South Walser German of Formazza/Pomatt)

- Albert Bächtold (1891–1981), De goldig Schmid; Wält uhni Liecht; De Studänt Räbme; Pjotr Ivanowitsch (Schaffhausen dialect of Klettgau)

- Ernst Burren (born 1944), Dr Schtammgascht; Näschtwermi (Solothurn dialect)

- August Corrodi (1826–1885), De Herr Professer; De Herr Vikari; De Herr Dokter (Zurich dialect)

- Barbara Egli (1918–2005), Wildi Chriesi (Zurich Oberland dialect)

- Fritz Enderlin (1883–1971), De Sonderbunds-Chrieg, translated from C. F. Ramuz's French poem "La Grande Guerre du Sondrebond" (Upper Thurgovian dialect)

- Martin Frank (born 1950), Ter Fögi ische Souhung; La Mort de Chevrolet (Bernese dialect with Zurich interferences)

- Simon Gfeller (1868–1943), Ämmegrund; Drätti, Müetti u der Chlyn; Seminarzyt (Bernese dialect of Emmental)

- Georg Fient (1845–1915), Lustig G'schichtenä (Graubünden Walser dialect of Prättigau)

- Paul Haller (1882–1920), Maria und Robert (Western Aargau dialect)

- Frida Hilty-Gröbli (1893–1957), Am aalte Maartplatz z Sant Galle; De hölzig Matroos (St Gall dialect)

- Josef Hug (1903–1985), S Gmaiguet; Dunggli Wolgga ob Salaz (Graubünden Rhine Valley dialect)

- Guy Krneta (born 1964), Furnier (collection of short stories), Zmittst im Gjätt uss (prose), Ursle (Bernese dialect)

- Michael Kuoni (1838–1891), Bilder aus dem Volksleben des Vorder-Prättigau's (Graubünden Walser dialect of Prättigau)

- Maria Lauber (1891–1973), Chüngold; Bletter im Luft; Der jung Schuelmiischter (Bernese Oberland dialect)

- Pedro Lenz (born 1965), Plötzlech hets di am Füdle; Der Goalie bin ig (Bernese Dialect)

- Meinrad Lienert (1865–1933), Flüehblüemli; 's Mirli; Der Waldvogel (Schwyz dialect of Einsiedeln)

- Carl Albert Loosli (1877–1959), Mys Dörfli; Mys Ämmitaw; Wi's öppe geit! (Bernese dialect of Emmental)

- Kurt Marti (born 1921), Vierzg Gedicht ir Bärner Umgangssprache; Rosa Loui (Bernese dialect)

- Werner Marti (1920–2013), Niklaus und Anna; Dä nid weis, was Liebi heisst (Bernese dialect)

- Mani Matter (1936–1972), songwriter (Bernese dialect)

- Traugott Meyer (1895–1959), 's Tunnälldorf; Der Gänneral Sutter (Basel-Landschaft dialect)

- Gall Morel (1803–1872), Dr Franzos im Ybrig (Schwyz German of Iberg)

- Viktor Schobinger (born 1934), Der Ääschme trifft simpatisch lüüt and a lot of other Züri Krimi (Zurich dialect)

- Caspar Streiff (1853–1917), Der Heiri Jenni im Sunnebärg (Glarus dialect)

- Jakob Stutz (1801–1877), Gemälde aus dem Volksleben; Ernste und heitere Bilder aus dem Leben unseres Volkes (Zurich Oberland dialect)

- Rudolf von Tavel (1866–1934), Ring i der Chetti; Gueti Gschpane; Meischter und Ritter; Der Stärn vo Buebebärg; D'Frou Kätheli und ihri Buebe; Der Frondeur; Ds velorene Lied; D'Haselmuus; Unspunne; Jä gäl, so geit's!; Der Houpme Lombach; Götti und Gotteli; Der Donnergueg; Veteranezyt; Heinz Tillman; Die heilige Flamme; Am Kaminfüür; Bernbiet; Schweizer daheim und draußen; Simeon und Eisi; Geschichten aus dem Bernerland (Bernese dialect)[38]

- Alfred Tobler (1845–1923), Näbes oß mine Buebejohre (Appenzell dialect)

- Johann Martin Usteri (1763–1827), Dichtungen in Versen und Prosa (Zurich German)

- Hans Valär (1871–1947), Dr Türligiiger (Graubünden Walser dialect of Davos)

- Bernhard Wyss (1833–1889), Schwizerdütsch. Bilder aus dem Stilleben unseres Volkes (Solothurn dialect)

Parts of the Bible were translated in different Swiss German dialects, e.g.:[39]

- Ds Nöie Teschtamänt bärndütsch (Bernese New Testament, translated by Hans and Ruth Bietenhard, 1989)

- Ds Alte Teschtamänt bärndütsch (parts of the Old Testament in Bernese dialect, translated by Hans and Ruth Bietenhard, 1990)

- D Psalme bärndütsch (Psalms in Bernese dialect, translated by Hans, Ruth and Benedikt Bietenhard, 1994)

- S Nöi Teschtamänt Züritüütsch (Zurich German New Testament, translated by Emil Weber, 1997)

- D Psalme Züritüütsch (Psalms in Zurich German, translated by Josua Boesch, 1990)

- Der guet Bricht us der Bible uf Baselbieterdütsch (parts of the Old and the New Testament in Basel dialect, 1981)

- S Markus Evangelium Luzärntüütsch (Gospel of Mark in Lucerne dialect, translated by Walter Haas, 1988)

- Markusevangeeli Obwaldnerdytsch (Gospel of Mark in the Obwalden dialect, translated by Karl Imfeld, 1979)

See also

Notes

- Because of the many different dialects, and because there is no defined orthography for any of them, many different spellings can be found.

References

- "Sprachen, Religionen – Daten, Indikatoren: Sprachen – Üblicherweise zu Hause gesprochene Sprachen" [Languages, Religions - Data, Indicators: Languages - Languages commonly spoken at home] (official site) (in German, French, and Italian). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

Zu Hause oder mit den Angehörigen sprechen 60,1% der betrachteten Bevölkerung hauptsächlich Schweizerdeutsch

[At home or with relatives, 60.1% of the population considered mainly speak Swiss German] - "Swiss German". IANA language subtag registry. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Central Alemannic | UNESCO WAL".

- R.E. Asher; Christopher Moseley (19 April 2018). Atlas of the World's Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-317-85108-0.

- D. Gorter; H. F. Marten; L. Van Mensel (13 December 2011). Minority Languages in the Linguistic Landscape. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-230-36023-5.

- "Family: Alemannic". Glottolog. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- "10vor10 – Nachrichtenmagazin von Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen" (in German). 3sat – ZDF ORF SRG ARD, the television channel collectively produced by four channels from three countries. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

Swiss German talks and interviews on the daily night news show 10vor10 by the major German Swiss channel SRF1 is consistently subtitled in German on 3sat

- See, for instance, an Examination of Swiss German in and around Zürich, a paper that presents the differences between Swiss German and High German.

- Statistik, Bundesamt für. "Schweizerdeutsch und Hochdeutsch in der Schweiz - Analyse von Daten aus der Erhebung zur Sprache, Religion und Kultur 2014 | Publikation". Bundesamt für Statistik (in German). Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Thompson, Chad (1994). "The Languages of the Amish of Allen County, Indiana: Multilingualism and Convergence". Anthropological Linguistics. Spring. 36 (1): 69–91. JSTOR 30028275.

- "hochdeutsche Lautverschiebung - Übersetzung Englisch-Deutsch". www.dict.cc.

- "High German consonant shift - Übersetzung Englisch-Deutsch". www.dict.cc.

- Fleischer & Schmid (2006:245)

- Fleischer & Schmid (2006:244s.)

- Astrid Krähenmann: Quantity and prosodic asymmetries in Alemannic. Synchronic and diachronic perspectives. de Gruyter, Berlin 2003. ISBN 3-11-017680-7

- Russ, Charles V. J. (1990). High Alemmanic. The Dialects of Modern German: a Linguistic Survey: Routledge. pp. 364–393.

- Werner König: dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1989. ISBN 3-423-03025-9

- Marti, Werner (1985), Berndeutsch-Grammatik, Bern: Francke

- Andreas Lötscher: Schweizerdeutsch – Geschichte, Dialekte, Gebrauch. Huber, Frauenfeld/Stuttgart 1983 ISBN 3-7193-0861-8

- See Rudolf Hotzenköcherle, Rudolf Trüb (eds.) (1975): Sprachatlas der deutschen Schweiz II 261s.

- Shieber, Stuart (1985), "Evidence against the context-freeness of natural language" (PDF), Linguistics and Philosophy, 8 (3): 333–343, doi:10.1007/BF00630917, S2CID 222277837.

- Glaser, Elvira; Frey, Natascha (2011). "Empirische Studien zur Verbverdoppelung in schweizerdeutschen Dialekten" (PDF). Linguistik Online. 45 (1): 3–7. doi:10.5167/uzh-52463. ISSN 1615-3014. S2CID 189169085.

- Brandner, Ellen; Salzmann, Martin (2012). Ackema, Peter; Alcorn, Rhona; Heycock, Caroline; Jaspers, Dany; van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen; Vanden Wyngaerd, Guido (eds.). "Crossing the lake: Motion verb constructions in Bodensee-Alemannic and Swiss German". Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 191: 67–98. doi:10.1075/la.191.03bra.

- Lötscher, Andreas (1993), Abraham, Werner; Bayer, Josef (eds.), "Zur Genese der Verbverdopplung bei gaa, choo, laa, aafaa ("gehen", "kommen", "lassen", "anfangen") im Schweizerdeutschen", Dialektsyntax, Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft (in German), Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 180–200, doi:10.1007/978-3-322-97032-9_9, ISBN 978-3-322-97032-9, retrieved 26 November 2021

- Brandner, Ellen; Salzmann, Martin (2011). Glaser, Elvira; Schmidt, Jürgen E.; Frey, Natascha (eds.). Die Bewegungverbkonstruktion im Alemannischen : Wie Unterschiede in der Kategorie einer Partikel zu syntaktischer Variation führen (in German). pp. 47–76. ISBN 978-3-515-09900-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Andres, Marie-Christine (1 January 2011). "Verdopplung beim Verb afaa im nord-östlichen Aargau". Linguistik Online (in German). 45 (1). doi:10.13092/lo.45.385. ISSN 1615-3014.

- Gappisch, Katja Schlatter (1 January 2011). "Die Verdopplung des Verbs laa 'lassen' im Zürichdeutschen". Linguistik Online (in German). 45 (1). doi:10.13092/lo.45.387. ISSN 1615-3014.

- Glaser, Elvira; Frey, Natascha. "Doubling Phenomena in Swiss German Dialects" (PDF). University of Zurich.

- Schaengold, Charlotte Christ (1999). "Short-form "Doubling Verbs" in Schwyzerdütsch". hdl:1811/81985.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kobel, Thomas Martin (14 August 2020). Bedeutet Är isch ga schwümme das gleiche wie Er ist schwimmen? Eine empirische Untersuchung zu den Perfektformen der schweizerdeutschen Verbverdoppelung und zur Funktion des Absentivs (single thesis). Bern: Universität Bern. doi:10.24442/boristheses.2128.

- Schweizerisches Idiotikon, Volume II, pages 511-512

- Grüezi - Schweizerisches Idiotikon

- Cf. the entry "bivouac" of the Online Etymology Dictionary

- Entry Deutsch ('German') Archived 9 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

- Entry Dialektliteratur ('dialect literature') in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

- Walter Haas: Dialekt als Sprache literarischer Werke. In: Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Ed. by Werner Besch, Ulrich Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke, Herbert Ernst Wiegand. 2nd half-volume. Berlin / New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1983, pp. 1637–1651.

- Dieth, Eugen: Schwyzertütschi Dialäktschrift. Dieth-Schreibung. 2nd ed. revised and edited by Christian Schmid-Cadalbert, Aarau: Sauerländer, 1986. ISBN 3-7941-2832-X

- "DSTIMM VO DE SCHWIIZ: PUBLICATION FOR SWISS GERMAN DIALECTS IN NORTH AMERICA". Iwaynet. Archived from the original on 8 August 2006.

- "Mundartübersetzungen – Bibel und Gesangbuch".

Bibliography

- Albert Bachmann (ed.), Beiträge zur schweizerdeutschen Grammatik (BSG), 20 vols., Frauenfeld: Huber, 1919–1941.

- Fleischer, Jürg; Schmid, Stephan (2006), "Zurich German", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (2): 243–253, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002441, S2CID 232347372

- Rudolf Hotzenköcherle (ed.), Beiträge zur schweizerdeutschen Mundartforschung (BSM), 24 vols., Frauenfeld: Huber, 1949–1982.

- Rudolf Hotzenköcherle, Robert Schläpfer, Rudolf Trüb (ed.), Sprachatlas der deutschen Schweiz. Bern/Tübingen: Francke, 1962–1997, vol. 1–8. – Helen Christen, Elvira Glaser, Matthias Friedli (ed.), Kleiner Sprachatlas der deutschen Schweiz. Frauenfeld: Huber, 2010 (and later editions), ISBN 978-3-7193-1524-5.

- Verein für das Schweizerdeutsche Wörterbuch (ed.), Schweizerisches Idiotikon: Wörterbuch der schweizerdeutschen Sprache. Frauenfeld: Huber; Basel: Schwabe, 17 vols. (16 complete), 1881–, ISBN 978-3-7193-0413-3.

External links

- Chochichästli-Orakel – choose the Swiss German words you would normally use and see how well this matches the dialect of your area. (in German)

- Dialekt.ch a site with sound samples from different dialects. (in German)

- Schweizerisches Idiotikon The homepage of the Swiss national dictionary.

- One poem in 29 Swiss dialects (in German and English)

- Zürich's Swiss German morphology and lexicon