Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was a regional power based in the Punjab region of South Asia.[8] It existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahore, to 1849, when it was defeated and conquered by the British East India Company in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. It was forged on the foundations of the Khalsa from a collection of autonomous misls.[1][9] At its peak in the 19th century, the empire extended from Gilgit and Tibet in the north to the deserts of Sindh in the south and from the Khyber Pass in the west to the Sutlej in the east as far as Oudh.[10][11] It was divided into four provinces: Lahore, which became the Sikh capital; Multan; Peshawar; and Kashmir from 1799 to 1849. Religiously diverse, with an estimated population of 4.5 million in 1831 (making it the 19th most populous country at the time),[12] it was the last major region of the Indian subcontinent to be annexed by the British Empire. Some of the notable Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Empire were Misr Diwan Chand, Hari Singh Nalwa and Diwan Mokham Chand.

Sikh Empire Sarkār-i-Khālsa Khālasā Rāj | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1799–1849 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: ਅਕਾਲ ਸਹਾਇ Akāl Sahāi "With God's Grace" | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: ਦੇਗ ਤੇਗ ਫ਼ਤਿਹ Dēġ Tēġ Fatih "Victory to Charity and Arms" | |||||||||||||||||||||

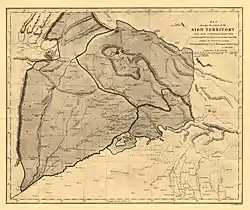

Sikh Empire at the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Court language | Persian[1][2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spoken languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1801–1839 | Ranjit Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1839 | Kharak Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1839–1840 | Nau Nihal Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1841–1843 | Sher Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1843–1849 | Duleep Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1840–1841 | Chand Kaur | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1843–1846 | Jind Kaur | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Wazir | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1799–1818 | Khushal Singh Jamadar[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1818–1843 | Dhian Singh Dogra | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1843–1844 | Hira Singh Dogra | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 14 May – 21 September 1845 | Jawahar Singh Aulakh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1845–1846 | Lal Singh | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 31 January – 9 March 1846 | Gulab Singh[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Capture of Lahore by Ranjit Singh | 7 July 1799 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• End of Second Anglo-Sikh War | 29 March 1849 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1839[6] | 520,000 km2 (200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1800s | 12,000,000[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Nanak Shahi Sikke | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Punjab |

|---|

_with_cities.png.webp) |

|

History of Pakistan History of India |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

The formation of the empire began with the capture of Lahore from its Durrani ruler, Zaman Shah Durrani. Ranjit Singh was proclaimed as Maharaja of the Punjab on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with Vaisakhi), creating a unified political state. Sahib Singh Bedi, a descendant of Guru Nanak, conducted the coronation.[13] The formation of the empire was followed by the progressive expulsion of Afghans from Punjab by capitalizing off Afghan decline in the Afghan-Sikh Wars, and the unification of the separate Sikh misls. Ranjit Singh rose to power in a very short period, from a leader of a single misl to finally becoming the Maharaja of Punjab. He began to modernise his army, using the latest training as well as weapons and artillery. After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the empire was weakened by the British East India Company stoking internal divisions and political mismanagement. Finally, in 1849, the state was dissolved after the defeat in the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

Background

The foundation of the Sikh Empire can be traced to as early as 1707, the year of Aurangzeb's death and the start of the downfall of the Mughal Empire. With the Mughals significantly weakened, the Sikh army, known as the Dal Khalsa, a rearrangement of the Khalsa inaugurated by Guru Gobind Singh, led expeditions against them and the Afghans in the west. This led to a growth of the army which split into different confederacies or semi-independent misls. Each of these component armies controlled different areas and cities. However, in the period from 1762 to 1799, Sikh commanders of the misls appeared to be coming into their own as independent.

Mughal rule of Punjab

Sikhism began during the conquest of North India by Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire. His grandson, Akbar, supported religious freedom and after visiting the langar of Guru Amar Das got a favourable impression of Sikhism. As a result of his visit, he donated land to the langar and the Mughals did not have any conflict with Sikh gurus until his death in 1605.[14]

His successor Jahangir, saw the Sikhs as a political threat. He ordered Guru Arjun Dev, who had been arrested for supporting the rebellious Khusrau Mirza,[15] to change the passage about Islam in the Adi Granth. When the Guru refused, Jahangir ordered him to be put to death by torture.[16] Guru Arjan Dev's martyrdom led to the sixth Guru, Guru Hargobind, declaring Sikh sovereignty in the creation of the Akal Takht and the establishment of a fort to defend Amritsar.[17]

Jahangir attempted to assert authority over the Sikhs by jailing Guru Hargobind at Gwalior Fort, but released him after a number of years when he no longer felt threatened. The Sikh community did not have any further issues with the Mughal empire until the death of Jahangir in 1627. The succeeding son of Jahangir, Shah Jahan, took offence at Guru Hargobind's "sovereignty" and after a series of assaults on Amritsar forced the Sikhs to retreat to the Sivalik Hills.[17]

The next guru, Guru Har Rai, maintained the guruship in these hills by defeating local attempts to seize Sikh land and playing a neutral role in the power struggle between two of the sons of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh, for control of the Mughal Empire. The ninth Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, moved the Sikh community to Anandpur and travelled extensively to visit and preach in defiance of Aurangzeb, who attempted to install Ram Rai as new guru. Guru Tegh Bahadur aided Kashmiri Pandits in avoiding conversion to Islam and was arrested by Aurangzeb. When offered a choice between conversion to Islam and death, he chose to die rather than compromise his principles and was executed.[18]

Formation of the Khalsa

Guru Gobind Singh assumed the guruship in 1675 and to avoid battles with Sivalik Hill rajas moved the guruship to Paunta. There he built a large fort to protect the city and garrisoned an army to protect it. The growing power of the Sikh community alarmed the Sivalik Hill rajas, who attempted to attack the city, but Guru Gobind Singh's forces routed them at the Battle of Bhangani. He moved on to Anandpur and established the Khalsa, a collective army of baptised Sikhs, on 30 March 1699.[19]

The establishment of the Khalsa united the Sikh community against various Mughal-backed claimants to the guruship.[20] In 1701, a combined army of the Sivalik Hill rajas and the Mughals under Wazir Khan attacked Anandpur. The Khalsa retreated but regrouped to defeat the Mughals at the Battle of Muktsar. In 1707, Guru Gobind Singh accepted an invitation by Aurangzeb's successor Bahadur Shah I to meet him. The meeting took place at Agra on 23 July 1707.[19]

Banda Singh Bahadur

In August 1708, Guru Gobind Singh visited Nanded. There he met a Bairāgī recluse, Madho Das, who converted to Sikhism, rechristened as Banda Singh Bahadur.[19][21] A short time before his death, Guru Gobind Singh ordered him to reconquer Punjab region and gave him a letter that commanded all Sikhs to join him. After two years of gaining supporters, Banda Singh Bahadur initiated an agrarian uprising by breaking up the large estates of Zamindar families and distributing the land to the poor peasants who farmed the land.[22]

Banda Singh Bahadur started his rebellion with the defeat of Mughal armies at Samana and Sadhaura and the rebellion culminated in the defeat of Sirhind. During the rebellion, Banda Singh Bahadur made a point of destroying the cities in which Mughals had been cruel to the supporters of Guru Gobind Singh. He executed Wazir Khan in revenge for the deaths of Guru Gobind Singh's sons and Pir Budhu Shah after the Sikh victory at Sirhind.[23]

He ruled the territory between the Sutlej river and the Yamuna river, established a capital in the Himalayas at Lohgarh and struck coinage in the names of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh.[22] In 1716, his army was defeated by the Mughals after he attempted to defend his fort at Gurdas Nangal. He was captured along with 700 of his men and sent to Delhi, where they were all tortured and executed after refusing to convert to Islam.[24]

History

Dal Khalsa period

Sikh Confederacy

The period from 1716 to 1799 was a highly turbulent time politically and militarily in the Punjab region. This was caused by the overall decline of the Mughal empire[25] that left a power vacuum in the region that was eventually filled by the Sikhs of the Dal Khalsa, meaning "Khalsa army" or "Khalsa party". In the late 18th century, after defeating several invasions by the Afghan rulers of the Durrani Empire and their allies,[26] remnants of the Mughals and their administrators, the Mughal-allied Hindu hill-rajas of the Sivalik Hills,[27][28] and hostile local Muslims siding with other Muslim forces.[26] The Sikhs of the Dal Khalsa eventually formed their own independent Sikh administrative regions, Misls, derived from a Perso-Arabic term meaning 'similar', headed by Misldars. These Misls were united in large part by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

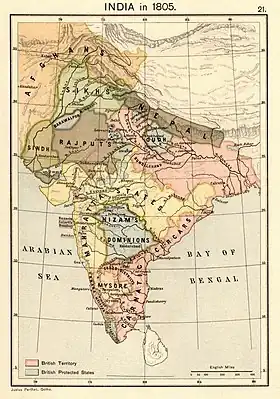

Cis-Sutlej states

The Cis-Sutlej states were a group of Sikh[29] states in the Punjab region lying between the Sutlej River to the north, the Himalayas to the east, the Yamuna River and Delhi district to the south, and Sirsa District to the west. The Cis-Sutlej states included Kalsia, Kaithal, Patiala State, Nabha State, Jind State, Thanesar, Maler Kotla, Ludhiana, Kapurthala State, Ambala, Ferozpur and Faridkot State, among others. These states fell under the suzerainty of the Scindhia, appointed by Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II as viceregent (Vakil-i-Mutlaq) of the Mughal empire,[30][31] after a brief Sikh-Maratha treaty in 1785 where according to the treaty, Scindhia would recognize the political supremacy of the Sikhs in the Punjab whereas the Sikhs would forbear from attacking the adjoining territories of Delhi.[32] Before the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803–1805, the Marathas lost all influence on the territory to the British East India Company.[33][34]

The Cis-Sutlej state was ruled by many chiefs though the region was under the Mughal Empire.[31] Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II's viceregent Afrasiyab was killed by Zain-ul-Abidin Khan on 2 November 1784, thus leaving no one to appoint as the next viceregent.[35] Thus Mughal Emperor appointed Mahadji Sindhia as viceregent (Vakil-i-Mutlaq) of the Mughal empire as Shah Alam II knew that Sindhia is the only one who would remain acquiescent to him and would be able to maintain peace and order in his kingdom.[36] The Maratha-Sikh treaty on 10 May 1785 made an establishment of the small Cis-Sutlej states, protected states of Scindia Dynasty,[37] on behalf of Mughals with Mahadji Scindia deputed the Vakil-i-Mutlaq (Regent of the Mughal empire) of Mughal affairs in 1784.[30][31] Therefore, Mahadji as newly appointed viceregent of the Mughal Emperor, tried to come to an agreement with the Cis-Sutlej chiefs and concluded a treaty on 10 May 1785.[38] According to the treaty, Mahadji would recognize the political supremacy of the Sikhs in the Punjab whereas the Sikhs would forbear from attacking the adjoining territories of Delhi.[32] Additionally, the chiefs would join Sindhia's army with at least 5,000 horses and in return would receive a land grant worth million rupees and the chiefs would not meddle in the affairs outside of their territory.[39][31] Additionally, it was agreed that any territories conquered through the joint alliance of Sikhs and the Marathas, the Sikhs would keep one-third of the territories and the enemies of both the parties would be considered mutual.[40] However the treaty fell apart as the chiefs did not observe the terms of the treaty.[38][41] In 1789, again a peaceful agreement was set in place where Sindhia legitamized the chiefs to collect tributes from the villages as the purpose behind Mahadji's policy was to win over the chiefs by friendship, but this policy too failed.[38]

After Mahadji's death in 1794, Daulat Rao was made his replacement, under whom the unstable conditions continued against the chiefs till the Second Anglo-Maratha War from 1803–1805, losing any influence over Cis-Sutlej state and parts of Uttar Pradesh, which he administered on behalf of the Mughal Emperor.[42][43]

Following the Second Anglo-Maratha War, in 1806, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington drafted a treaty granting independence to the Sikh clans east of the Sutlej River in exchange for their allegiance to the British General Gerard Lake acting on his dispatch.[44][45]

Ranjit Singh led three expeditions into Cis-Sutlej states in 1806, 1807 and 1808, seizing many territories, particularly 45 district subdivisions or administrative units (parganas) and then distributed them among different chiefs who would pay annual tributes of certain amount as recognition of Ranjit Singh's supremacy.[46] Ranjit Singh gave some territories of Cis-Sutlej to his mother in law Rani Sada Kaur and granted a good deal of villages to his general Dewan Mokham Chand.[46] In all 45 paraganas, Ranjit Singh assigned salaried agents to different territories who sustained some soldiers for internal administration to retrieve revenues from lands.[46] Some of the important vassal territories of Sikh empire were, Anandpur, Rupar, Himmatpur, Wadni, Harikepatan, Firozpur and Mamdot.[47]

On 9 February, 1809, David Ochterlony of the British East India company issued a proclamation declaring the Cis-Sutlej states to be under British protection which concluded with a treaty of friendship on 25 April 1809 between the British East India company and Ranjit Singh, emperor of the Sikh Empire, recognised the territories of 45 paraganas, north of the river Sutlej under the aegis of Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire and in return Ranjit Singh recognised British protection to the Cis-Sutlej states. The river Sutlej became the boundary between Ranjit Singh's dominion and the British territory.[48]

Ranjit Singh possessed 45 Taluqas in the Cis-Sutlej states, wholly or in share with others on the British side of the river Sutlej.[46] On 29 July 1809, David Ochterlony recognized large territory along river Sutlej from Chamkaur to Harikepatan and Kot Kapura as directly under Ranjit Singh's control.[49] Dewan Mokham Chand, Ranjit Singh's commander was granted 102 villages in the tehsil of Dharamkot, Zira and Kot Kapura, which also belonged to Ranjit Singh.[49] Raja of Jind, maternal uncle of Ranjit Singh, was granted 90 villages in the paraganah of Ludhiana-Sirhind[49] Raja of Kapurthala, brother of Ranjit Singh, was awarded 106 villages in the tehsil of Talwandi and Naraingarh.[49] Other rewards as part of the treaty were, 38 villages secured to Raja Jaswant Singh of Nabha State, 32 villages in the tehsil of Baddowal secured to Gurdit Singh of Ladwa, 36 villages in the tehsil of Ghungrana secured to Karam Singh Nagia, 62 villages in the tehsil of Dharamkot granted to Garbha Singh of Bharatgarh, many number of villages granted to Jodh Singh of Kalsia, Basant Singh, Atar Singh, Jodh Singh of Bassia and Ranjit Singh's mother in law Sada Kaur was granted with Himmatpur-Wadni.[49] The recipients were granted the territories under the condition of submission to Ranjit Singh's supremacy.[50]

On 17 March 1828, Captain W. Murray prepared a list of 45 Taluqas in south of Satluj that belonged and were claimed by Ranjit Singh.[50] They were: Anandpur, Makhowal, Mattewala, Bajr, Goewal, Howab, Karesh, Sujarwala, Sohera, Sailbah, Khai, Muedkoh, Wazirpur, Kunki, Saholi, Basi, Bharog, Jagraon, Kot Isa Khan, Mahani, Khaspura, Molanwala, Naraingarh, Sadar Khan, Tohra, Mari, Machhiwara, Kotari, Puwa, Want, part of Kotlah, Kot Guru Har Sahe, Dharamkot, Rajwana, Fatahgarh, Kala Majri, Chuhar Chak, Dhilwan, Talwandi Sayyidan, Jhandianah, Buthor, Ranian, Baholpur, Bharatgarh, Chanelgarh, Lohangarh, Phillaur district, Firozpur, Nurpur, Khaira, Sohala, Todarpur, Tughal, part of Kotlah, Ghungrana, Rumanwala, Mamdot, Sanehwal, Rasulpur, Aitiana, Himmatpur, Pattoki, Wadni, Moga, Mohlan, Zira, Behekbodia, Bhagra, Hitawat, Jinwar, Kot Kapura, Muktsar, Kenoan, Singhanwala, Suhewaron, Chamkaur and Molwal.[50]

Intra-Misl Wars

After the reign of Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, the Sikh Misls became divided and fought each other. A sort of 'Cold War' broke out with the Bhangi, Nakkai, Dalelwala and Ramgharia Misls verses Sukerchakia, Ahluwalia, Karor Singhia and Kaniyeha. The Shaheedan, Nishania and Singhpuria also allied but did not engage in warfare with the others and continued the Dal Khalsa.

The Phulkian Misl was excommunicated from the confederacy. Rani Sada Kaur of the Kanhaiya Misl rose in the vacuum and destroyed the power of the Bhangis. She later gave her throne to Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Empire

The formal start of the Sikh Empire began with the unification of the Misls by 1801, creating a unified political state. All the Misl leaders, who were affiliated with the army, were the nobility with usually long and prestigious family backgrounds in Sikh history.[1]

The main geographical footprint of the empire was from the Punjab region to Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, Sindh in the south, and Tibet in the east.[51]

In 1799 Ranjit Singh moved the capital to Lahore from Gujranwala, where it had been established in 1763 by his grandfather, Charat Singh.[52]

Ranjit Singh annexed the Sial State, a local Muslim-ruled chieftaincy, after invading Jhang in 1807.[53] The basis for this annexation was that the local ruler of Jhang, Ahmad Khan Sial, was conspiring with Nawab Muzaffar Khan of Multan and had signed a secret treaty with the latter.[53]

Hari Singh Nalwa was Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Khalsa Army from 1825 to 1837.[54] He is known for his role in the conquests of Kasur, Sialkot, Multan, Kashmir, Attock and Peshawar. Nalwa led the Sikh army in freeing Shah Shuja from Kashmir and secured the Koh-i-Nor diamond for Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He served as governor of Kashmir and Hazara and established a mint on behalf of the Sikh empire to facilitate revenue collection. His frontier policy of holding the Khyber Pass was later used by the British Raj. Nalwa was responsible for expanding the frontier of Sikh empire to the Indus River. At the time of his death, the western boundary of the Sikh Empire was the Khyber Pass.

The Namgyal dynasty of Ladakh paid regular annual tribute to the Sikh Empire starting 1819 until 1834.[55] The tribute was paid to the local Sikh governors of Kashmir.[55] The Namgyal kingdom would later be conquered by the Dogras, under the leadership of Zorawar Singh.[56]

The domain of the Maqpon kingdom of Baltistan, based in Skardu, under the rule of Ahmad Shah Maqpon, was conquered in 1839–40 and its local ruler was deposed.[56][57][58][59] The Dogras at this time were under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire.[56]

During the Sino-Sikh War of 1841, the forces of the empire invaded the Tibetan Plateau, which was then under the control of the Qing dynasty.[60] However, this control was short-lived and the military of the empire was forced to retreat to Ladakh due to a counterattack by the Chinese and Tibetans.[60]

Geography

The Sikh Empire spanned a total of over 200,000 sq mi (520,000 km2) at its zenith.[61][62][63] Another more conservative estimate puts its total surface area during its zenith at 100,436 sq mi (260,124 km sq).[64]

The following modern-day political divisions made up the historical Sikh Empire:

- Punjab region, to Mithankot in the south

- Punjab, Pakistan, excluding Bahawalpur State

- Punjab, India, excluding the Cis-Sutlej states

- Himachal Pradesh, India, only the territories northwest of Sutlej river.

- Jammu Division, Jammu and Kashmir, India and Pakistan (1808–1846)

- Kashmir, from 5 July 1819 to 15 March 1846, India/Pakistan/China[65][66]

- Khyber Pass, Afghanistan/Pakistan[69]

- Peshawar, Pakistan[70] (taken in 1818, retaken in 1834)

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pakistan (documented from Hazara (taken in 1818, again in 1836) to Bannu)[71]

- Parts of Western Tibet,[72] China (briefly in 1841, to Taklakot),[73]

Jamrud District (Khyber Agency, Pakistan) was the westernmost limit of the Sikh Empire. The westward expansion was stopped in the Battle of Jamrud, in which the Afghans managed to kill the prominent Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa in an offensive, though the Sikhs successfully held their position at their Jamrud fort. Ranjit Singh sent his General Sirdar Bahadur Gulab Singh Powind thereafter as reinforcement and he crushed the Pashtun rebellion harshly.[74] In 1838, Ranjit Singh with his troops marched into Kabul to take part in the victory parade along with the British after restoring Shah Shoja to the Afghan throne at Kabul.[75]

Religious policy

The Sikh Empire was idiosyncratic in that it allowed men from religions other than their own to rise to commanding positions of authority.[76]

The Fakir brothers were trusted personal advisors and assistants as well as close friends to Ranjit Singh,[77] particularly Fakir Azizuddin, who would serve in the positions of foreign minister of the empire and translator for the maharaja, and played important roles in such important events as the negotiations with the British, during which he convinced Ranjit Singh to maintain diplomatic ties with the British and not to go to war with them in 1808, as British troops were moved along the Sutlej in pursuance of the British policy of confining Ranjit Singh to the north of the river, and setting the Sutlej as the dividing boundary between the Sikh and British empires;[78] negotiating with Dost Muhammad Khan during his unsuccessful attempt to retake Peshawar,[78] and ensuring the succession of the throne during the Maharaja's last days in addition to caretaking after a stroke, as well as occasional military assignments throughout his career.[79] The Fakir brothers were introduced to the Maharaja when their father, Ghulam Muhiuddin, a physician, was summoned by him to treat an eye ailment soon after his capture of Lahore.[80]

The other Fakir brothers were Imamuddin, one of his principal administration officers, and Nuruddin, who served as home minister and personal physician, were also granted jagirs by the Maharaja.[81]

Every year, while at Amritsar, Ranjit Singh visited shrines of holy people of other faiths, including several Muslim saints, which did not offend even the most religious Sikhs of his administration.[82] As relayed by Fakir Nuruddin, orders were issued to treat people of all faith groups, occupations,[83] and social levels equally and in accordance with the doctrines of their faith, per the Shastras and the Quran, as well as local authorities like judges and panches (local elder councils),[84] as well as banning forcible possession of others' land or of inhabited houses to be demolished.[85] There were special courts for Muslims which ruled in accordance to Muslim law in personal matters,[86] and common courts preceded over by judicial officers which administered justice under the customary law of the districts and socio-ethnic groups, and were open to all who wanted to be governed by customary religious law, whether Hindu, Sikh, or Muslim.[86]

One of Ranjit Singh's first acts after the 1799 capture of Lahore was to revive the offices of the hereditary Qazis and Muftis which had been prevalent in Mughal times.[86] Kazi Nizamuddin was appointed to decide marital issues among Muslims, while Muftis Mohammad Shahpuri and Sadulla Chishti were entrusted with powers to draw up title-deeds relating to transfers of immovable property.[86] The old mohalladari system was reintroduced with each mahallah, or neighborhood subdivision, placed under the charge of one of its members. The office of Kotwal, or prefect of police, was conferred upon a Muslim, Imam Bakhsh.[86]

Generals were also drawn from a variety of communities, along with prominent Sikh generals like Hari Singh Nalwa, Fateh Singh Dullewalia, Nihal Singh Atariwala, Chattar Singh Attariwalla, and Fateh Singh Kalianwala; Hindu generals included Misr Diwan Chand and Dewan Mokham Chand Nayyar, his son, and his grandson; and Muslim generals included Ilahi Bakhsh and Mian Ghaus Khan; one general, Balbhadra Kunwar, was a Nepalese Gurkha, and European generals included Jean-Francois Allard, Jean-Baptiste Ventura, and Paolo Avitabile.[87] other notable generals of the Sikh Khalsa Army were Veer Singh Dhillon, Sham Singh Attariwala, Mahan Singh Mirpuri, and Zorawar Singh Kahluria, among others.

The appointment of key posts in public offices was based on merit and loyalty, regardless of the social group or religion of the appointees, both in and around the court, and in higher as well as lower posts. Key posts in the civil and military administration were held by members of communities from all over the empire and beyond, including Sikhs, Muslims, Khatris, Brahmins, Dogras, Rajputs, Pashtuns, Europeans, and Americans, among others,[88] and worked their way up the hierarchy to attain merit. Dhian Singh, the prime minister, was a Dogra, whose brothers Gulab Singh and Suchet Singh served in the high-ranking administrative and military posts, respectively.[88] Brahmins like finance minister Raja Dina Nath, Sahib Dyal, and others also served in financial capacities.[87]

Muslims in prominent positions included the Fakir brothers, Kazi Nizamuddin, and Mufti Muhammad Shah, among others. Among the top-ranking Muslim officers there were two ministers, one governor and several district officers; there were 41 high-ranking Muslim officers in the army, including two generals and several colonels,[87] and 92 Muslims were senior officers in the police, judiciary, legal department and supply and store departments.[87] In artillery, Muslims represented over 50% of the numbers while the cavalry had some 10% Muslims from among the troopers.[89]

Thus, the government was run by an elite corps drawn from many communities, giving the empire the character of a secular system of government, even when built on theocratic foundations.[90]

A ban on cow slaughter, which can be related to Hindu sentiments, was universally imposed in the Sarkar Khalsaji.[91][92] Ranjit Singh also donated large amounts of gold for the plating of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple's dome.[93][94]

The Sikhs attempted not to offend the prejudices of Muslims, noted Baron von Hügel, the Austrian botanist and explorer,[95] yet the Sikhs were described as harsh. In this regard, Masson's explanation is perhaps the most pertinent: "Though compared to the Afghans, the Sikhs were mild and exerted a protecting influence, yet no advantages could compensate to their Mohammedan subjects, the idea of subjection to infidels, and the prohibition to slay kine, and to repeat the azan, or 'summons to prayer'."[96] According to Chitralekha Zutshi and William Roe Polk, Sikh governors adopted policies that alienated the Muslim population such as the ban on cow slaughter and the azan (the Islamic call to prayer), the seizure of mosques as property of the state, and imposed ruinous taxes on Kashmiri Muslims causing a famine in 1832. In addition, begar (forced labour) was imposed by the Sikh administration to facilitate the supply of materials to the imperial army, a policy that was augmented by the successive Dogra rulers.[97][98][99] These policies led the Kashmiri Muslim population to emirgate en masse to more lenient neighboring countries, particularly Ladakh.[100] As a symbolic assertion of power, the Sikhs regularly desecrated Muslim places of worship, including closing of the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar and the conversion of the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore to an ammunition store and horse stable, but the empire still maintained Persian administrative institutions and court etiquette; the Sikh silver rupees were minted on the Mughal standard with Persian legends.[101][102]

In 1839, a major pogrom, called the Allahdad, targeting the local Jews of Mashhad in Qajar Persia had occurred.[103] A group of Persian Jewish refugees from Mashhad, escaping persecution back home in Qajar Persia, settled in the Sikh Empire around the year 1839.[103] Most of the Jewish families settled in Rawalpindi (specifically in the Babu Mohallah neighbourhood) and Peshawar.[104][105][106][107][103] Most of these Jews would leave for India during the partition of 1947.[108][103]

Christian missionaries had been active in the Punjab even prior to the dissolution of the empire in 1849.[109]

Administration

The empire was divided into various provinces (known as Subas), them namely being:[64]

| No. | Name | Estimated population (1838) | Major population centre |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Lahore Suba | 1,900,000 | Lahore |

| 2. | Multan Suba | 750,000 | Multan |

| 3. | Peshawar Suba | 550,000 | Peshawar |

| 4. | Derajat Suba | 600,000 | Dera Ghazi Khan, Dera Ismail Khan |

| 5. | Jammu and Hill States Suba | 1,100,000 | Srinagar |

Demography

The population of the Sikh empire during the time of Ranjit Singh's rule was estimated to be around 12 million people.[7] There were 8.4 million Muslims, 2.88 million Hindus and 722,000 Sikhs.[110]

The religious demography of the empire is estimated to have been just over 10% to 12%[112] Sikh, 80% Muslim, and just under 10% Hindu. Surjit Hans gave different numbers by retrospectively projecting the 1881 census, putting Muslims at 51%, Hindus at 40% and Sikhs at around 8%, the remaining 1% being Europeans.[113] The population was 3.5 million in 1831, according to Amarinder Singh's The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbar.[114] Hans Herrli in The Coins of the Sikhs estimated the total population of the empire to be around 5.35 million during 1838.[64]

An estimated 90% of the Sikh population at the time, and more than half of the total population, was concentrated in the upper Bari, Jalandhar, and upper Rachna Doabs, and in the areas of their greatest concentration formed about one third of the population in the 1830s; half of the Sikh population of this core region was in the area covered by the later districts of Lahore and Amritsar.[112]

Economy

Revenue

| Sr | Particulars | Revenue in Rupees | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Land Revenue | ||

| 1.a | Tributary States | 5,65,000 | |

| 1.b | Farms | 1,79,85,000 | |

| 1.c | Eleemosynary | 20,00,000 | |

| 1.d | Jaghirs | 95,25,000 | |

| 2 | Customs | 24,00,000 | |

| Total | 3,24,75,000 | ||

Land revenue was the main source of income, accounting for about 70% of the state's income. Besides this, the other sources of income were customs, excises and monopolies.[116]

Decline

After Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, the empire was severely weakened by internal divisions and political mismanagement. This opportunity was used by the British East India Company to launch the First Anglo-Sikh War.

The Battle of Ferozeshah in 1845 marked many turning points, the British encountered the Punjab Army, opening with a gun-duel in which the Sikhs "had the better of the British artillery". As the British made advances, Europeans in their army were specially targeted, as the Sikhs believed if the army "became demoralized, the backbone of the enemy's position would be broken".[117] The fighting continued throughout the night. The British position "grew graver as the night wore on", and "suffered terrible casualties with every single member of the Governor General's staff either killed or wounded".[118] Nevertheless, the British army took and held Ferozeshah. British General Sir James Hope Grant recorded: "Truly the night was one of gloom and forbidding and perhaps never in the annals of warfare has a British Army on such a large scale been nearer to a defeat which would have involved annihilation."[118]

The reasons for the withdrawal of the Sikhs from Ferozeshah are contentious. Some believe that it was treachery of the non-Sikh high command of their own army which led to them marching away from a British force in a precarious and battered state. Others believe that a tactical withdrawal was the best policy.

The Sikh empire was finally dissolved at the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849 into separate princely states and the British province of Punjab. Eventually, a Lieutenant Governorship was formed in Lahore as a direct representative of the British Crown.

Timeline

- 1699: Formation of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh.

- 1710–1716: Banda Singh defeats the Mughals and declares Khalsa rule.

- 1716–1738: Turbulence, no real ruler; Mughals take back the control for two decades but Sikhs engage in guerrilla warfare

- 1733–1735: The Khalsa accepts, only to reject, the confederal status given by the Mughals.

- 1748–1757: Afghan invasion of Ahmad Shah Durrani

- 1761–1767: Recapture of Punjab region by Afghan in Third Battle of Panipat

- 1763–1774: Charat Singh Sukerchakia, Misldar of Sukerchakia misl, establishes himself in Gujranwala.

- 1764–1783: Baba Baghel Singh, Misldar of Singh Krora Misl, imposes taxes on the Mughals.

- 1783: Sikh capture of Delhi and the Red Fort from the Mughals

- 1773: Ahmad Shah Durrani dies and his son Timur Shah launches several invasions into Punjab.

- 1774–1790: Maha Singh becomes Misldar of the Sukerchakia misl.

Contemporary painting of the Battle of Sobraon in 1846.

Contemporary painting of the Battle of Sobraon in 1846. - 1790–1801: Ranjit Singh becomes Misldar of the Sukerchakia misl.

- 1799, formation of the Sikh Khalsa Army

- 12 April 1801 (coronation) – 27 June 1839: reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

- March 1809 – August 1809: Nepal–Sikh War

- 20 February 1810: Siege of Multan (1810)

- 1 June 1813: Ranjit Singh is given the Kohinoor Diamond.

- 13 July 1813: Battle of Attock, the Sikh Empire's first significant victory over the Durrani Empire.

- March – 2 June 1818: Battle of Multan, the 2nd battle in the Afghan–Sikh wars.

- 3 July 1819: Battle of Shopian

The charge of the British 16th Lancers at Aliwal on 28 January 1846, during the First Anglo-Sikh War

The charge of the British 16th Lancers at Aliwal on 28 January 1846, during the First Anglo-Sikh War - 14 March 1823: Battle of Nowshera

- 30 April 1837: Battle of Jamrud

- 27 June 1839 – 5 November 1840: Reign of Maharaja Kharak Singh

- 5 November 1840 – 18 January 1841: Chand Kaur is briefly Regent

- 18 January 1841 – 15 September 1843: Reign of Maharaja Sher Singh

- May 1841 – August 1842: Sino-Sikh war

- 15 September 1843 – 31 March 1849: Reign of Maharaja Duleep Singh

- 1845–1846: First Anglo-Sikh War

- 1848–1849: Second Anglo-Sikh War

List of rulers

| S. No. | Name | Portrait | Birth and death | Reign | Note | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maharaja Ranjit Singh |  |

13 November 1780 (Gujranwala) | 27 June 1839 (Lahore) | 12 April 1801 | 27 June 1839 | 38 years, 76 days | The first Sikh ruler | Stroke |

| 2 | Maharaja Kharak Singh |  |

22 February 1801 (Lahore) | 5 November 1840 (Lahore) | 27 June 1839 | 8 October 1839 | 103 days | Son of Ranjit Singh | Poisoning |

| 3 | Maharaja Nau Nihal Singh |  |

11 February 1820 (Lahore) | 6 November 1840 (Lahore) | 8 October 1839 | 6 November 1840 | 1 year, 29 days | Son of Kharak Singh | Assassinated |

| 4 | Maharani Chand Kaur |

|

1802 (Fatehgarh Churian) | 11 June 1842 (Lahore) | 6 November 1840 | 18 January 1841 | 73 days | Wife of Kharak Singh and the only female ruler of Sikh Empire | Abdicated |

| 5 | Maharaja Sher Singh |  |

4 December 1807 (Batala) | 15 September 1843 (Lahore) | 18 January 1841 | 15 September 1843 | 2 years, 240 days | Son of Ranjit Singh | Assassinated |

| 6 | Maharaja Duleep Singh |  |

6 September 1838 (Lahore) | 22 October 1893 (Paris) | 15 September 1843 | 29 March 1849 | 5 years, 195 days | Son of Ranjit Singh | Exiled |

| 7 | Maharani Jind Kaur (regent; nominal) |

|

1817 (Gujranwala) | 1 August 1863 (Kensington) | 15 September 1843 | 29 March 1849 | 5 years, 195 days | Wife of Ranjit Singh | Exiled |

Family tree

| Family tree of the Maharajas of the Sikh Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Ranjit Singh, c. 1830.[119]

Ranjit Singh, c. 1830.[119] Ranjit Singh listening to Guru Granth Sahib being recited near the Akal Takht and Golden Temple, Amritsar, Punjab, India.

Ranjit Singh listening to Guru Granth Sahib being recited near the Akal Takht and Golden Temple, Amritsar, Punjab, India. Sikh warrior helmet with butted mail neckguard, 1820–1840, iron overlaid with gold with mail neckguard of iron and brass

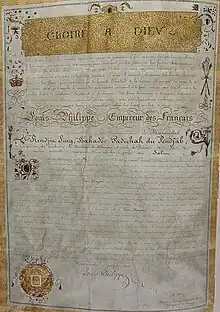

Sikh warrior helmet with butted mail neckguard, 1820–1840, iron overlaid with gold with mail neckguard of iron and brass A letter sent from the King of France, Louis-Philippe to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Ranjit Singh is addressed as “Rendjit Sing Bahador – Padichah du Pendjab”. 27 October 1835

A letter sent from the King of France, Louis-Philippe to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Ranjit Singh is addressed as “Rendjit Sing Bahador – Padichah du Pendjab”. 27 October 1835

See also

References

Citations

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 892.

- Grewal, J. S. (1990). The Sikhs of the Punjab, Chapter 6: The Sikh empire (1799–1849). The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-521-63764-3.

The continuance of Persian as the language of administration.

- Fenech, Louis E. (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press (US). p. 239. ISBN 978-0199931453.

We see such acquaintance clearly within the Sikh court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, for example, the principal language of which was Persian.

- Grewal, J.S. (1990). The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-521-63764-3. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 46–50.

- Singh, Amarpal (2010). The First Anglo-Sikh War. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2038-1.

By 1839, the year of his death, the Sikh kingdom extended from Tibet and Kashmir to Sind and from the Khyber Pass to the Himalayas in the east. It spanned 600 miles from east to west and 350 miles from north to south, comprising an area of just over 200,000 square miles.

- Singh, Pashaura (2016). "Sikh Empire". The Encyclopedia of Empire. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe314. ISBN 978-1118455074.

- K.S. Duggal (2015) [1989]. Ranjit Singh: A Secular Sikh Sovereign. Exoticindiaart.com. ISBN 978-8170172444. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Grewal, J. S. (1990). The Sikhs of the Punjab, Chapter 6: The Sikh empire (1799–1849). The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63764-3.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (1991). History of the Sikhs. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 201. ISBN 978-8121505154.

- Singh, Khushwant (2004). History of the Sikhs. Oxford University Press. p. viii. ISBN 978-0195673081.

- Amarinder Singh's The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbar

- The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, section Sāhib Siṅgh Bedī, Bābā (1756–1834).

- Kalsi 2005, pp. 106–107

- Markovits 2004, p. 98

- Melton, J. Gordon (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1163. ISBN 9781610690263. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Jestice 2004, pp. 345–346

- Johar 1975, pp. 192–210

- Ganda Singh. "Gobind Singh Guru (1666–1708)". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Jestice 2004, pp. 312–313

- "Banda Singh Bahadur". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Singh 2008, pp. 25–26

- Nesbitt 2005, p. 61

- Singh, Kulwant (2006). Sri Gur Panth Prakash: Episodes 1 to 81. Institute of Sikh Studies. p. 415. ISBN 978-8185815282.

- "Sikh Period – National Fund for Cultural Heritage". Heritage.gov.pk. 14 August 1947. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Meredith L. Runion The History of Afghanistan pp 70 Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 0313337985

- Patwant Singh (2007). The Sikhs. Crown Publishing Group. p. 270. ISBN 978-0307429339.

- "Sikhs' Relation with Hill States". www.thesikhencyclopedia.com. 19 December 2000. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Jayanta Kumar Ray (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education. p. 379. ISBN 978-8131708347.

- Ahmed, Farooqui Salma (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid ... Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-8131732021. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Chaurasia 2004, p. 167.

- Mittal, Satish Chandra (1986). Haryana, a Historical Perspective. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 11. ISBN 978-8171560837.

- Chaurasia 2004, p. 13.

- Jayanta Kumar Ray (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education. p. 379. ISBN 978-8131708347.

- Gupta 1978, p. 196.

- Gupta 1978, p. 197. "On the 4th December at another public darbar the Emperor bestowed the highest post of Vakahi-Mutlaq [Regent Plenipotentiary] on Mahadji Sindhia."

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. ISBN 978-0230328853.

By Mahadji Shinde's treaty of 1785 with the Sikhs, Maratha influence had been established over the divided Cis-Sutlej states. But at the end of the second Maratha war in 1806 that influence had been pass over to the British.

- Chaurasia 2004, p. 168.

- Sen 1994, p. 30.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1994). Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96 Volume 2. Popular Prakashan. p. 30. ISBN 978-8171547890.

- Gupta 1978, p. 216. "No sooner was the treaty signed than misgivings arose between them. The Sikhs did not wish to abide by the treaty."

- Chaurasia 2004, pp. 167–170.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (1978). History of the Sikhs: Sikh Domination of the Mughal Empire. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 196–216.

- Wellesley, Arthur (1837). The Despatches, Minutes, and Correspondance, of the Marquess Wellesley, K. G. During His Administration in India. pp. 264–267.

- Wellesley, Arthur (1859). Supplementary Despatches and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur, Duke of Wellington, K. G.: India, 1797–1805. Vol. I. pp. 269–279, 319.

"ART VI Scindiah to renounce all claims the Seik chiefs or territories" (p. 318)

- Gupta 1991, p. 83.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (1991). History of the Sikhs Volume 5. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 83–96. ISBN 978-8121505154.

- Chopra, P.N. (2003). "Defending British India Against Napoleon". A Comprehensive History of India, Volume 3. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 978-8120725065.

- Gupta 1991, p. 86.

- Gupta 1991, p. 87.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (1991). History of the Sikhs. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-8121505154.

- World and Its Peoples: Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. p. 411. ISBN 978-0761475712.

- Singh, Rishi (2014). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. Sage Publications India. ISBN 978-9351505044.

When Ranjit Singh realised that Ahmad Khan Sial of Jhang had concluded a secret treaty with Nawab Muzaffar Khan of Multan, he annexed Jhang in 1807 and gave Ahmad Khan a jagir at Mirowal near Amritsar.

- Roy, K.; Roy, L. D. H. K. (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-1136790874. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Petech, Luciano (1977). The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D. Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. p. 130.

- Huttenback, Robert A. (1961). "Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. 20 (4): 477–488. doi:10.2307/2049956. JSTOR 2049956. S2CID 162144034.

- Rieck, Andreas (1995). "The Nurbakhshis of Baltistan: Crisis and Revival of a Five Centuries Old Community". Die Welt des Islams. Hamburg. 35 (2): 159–188. doi:10.1163/1570060952597761. JSTOR 1571229. Retrieved 30 June 2023 – via JSTOR.

Thus Baltistan remained under local Rajas who paid only nominal allegiance to subsequent rulers of Kashmir until subdued by a Sikh army in 1840, and who stayed in office as jagirdars under the Hindu Dogra Maharajas (1846–1947) and even in Pakistan until 1972. ... As has been stated above, there are no reliable indicators for the extent to which Twelver Shi'ism had spread in Baltistan at the time of the Sikh conquest (1840).

- Mock, John; O'Neil, Kimberley (2002). Trekking in the Karakoram & Hindukush. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 302. ISBN 978-1740590860.

By the 18th century, fighting among the Maqpon princes led to a decline in Skardu's importance. The Sikhs, who inherited much of the Moghul empire, annexed Baltistan in 1840 and the Balti kingdoms' sovereignty ended.

- Baloch, Sikandar Khan (2004). In the Wonderland of Asia, Gilgit & Baltistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 127. ISBN 978-9693516142.

- Guo, Rongxing (2015). "Chapter 1: A Brief History of Tibet". China's Regional Development and Tibet. Springer. ISBN 978-9812879585.

In AD 1834, the Sikh empire invaded and annexed Ladakh-a culturally Tibetan region that was an independent kingdom at the time. Seven years later, a Sikh army invaded western Tibet from Ladakh, starting the Sino-Sikh War. A Qing-Tibetan army repelled the invaders but was in turn defeated when it chased the Sikhs into Ladakh. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Chushul between the Chinese and Sikh empires (Rubin 1960). As the Qing dynasty declined, its influence on Tibet weakened gradually. By the late nineteenth cen tury, Qing's authority over Tibet had become more symbolic.

- Manning, Stephen (2020). Bayonet to Barrage Weaponry on the Victorian Battlefield. Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1526777249.

The Sikh kingdom expanded from Tibet in the east to Kashmir in the west and from Sind in the south to the Khyber Pass in the north, an area of 200,000 square miles

- Barczewski, Stephanie (2016). Heroic Failure and the British. Yale University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0300186819.

…the Sikh state encompassed over 200,000 square miles (518,000 sq km)

- Khilani, N. M. (1972). British power in the Punjab, 1839–1858. Asia Publishing House. p. 251. ISBN 978-0210271872.

..into existence a kingdom of the Punjab of over 200,000 square miles

- Herrli, Hans (1993). The Coins of the Sikhs. p. 10.

- The Masters Revealed, (Johnson, p. 128)

- Britain and Tibet 1765–1947, (Marshall, p. 116)

- Pandey, Dr. Hemant Kumar; Singh, Manish Raj (2017). India's Major Military and Rescue Operations. Horizon Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-9386369390.

- Deng, Jonathan M. (2010). "Frontier: The Making of the Northern and Eastern Border in Ladakh From 1834 to the Present". SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 920.

- The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion, (Docherty, p. 187)

- The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion, (Docherty, pp. 185–187)

- Bennett-Jones, Owen; Singh, Sarina, Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway p. 199

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. vii.

- Kartar Singh Duggal (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. p. 131. ISBN 978-8170174103.

- Hastings Donnan, Marriage Among Muslims: Preference and Choice in Northern Pakistan, (Brill, 1997), 41.

- Encyclopædia Britannica – Ranjit Singh

- Kartar Singh Duggal (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-81-7017-410-3.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. ix.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 27.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 28.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 25.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. iv.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 3.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 19.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 17.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 18.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 20.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 23.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 22.

- Singh, Amarinder (2010). The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbar. Roli Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-81-7436-779-2.

- Waheeduddin 1981, p. 24.

- Lodrick, D. O. 1981. Sacred Cows, Sacred Places. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 145

- Vigne, G. T., 1840. A Personal Narrative of a Visit to Ghuzni, Kabul, and Afghanistan, and a Residence at the Court of Dost Mohammed, London: Whittaker and Co. p. 246 The Real Ranjit Singh; by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 2001, 2nd ed.

- Matthew Atmore Sherring (1868). The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Trübner & co. p. 51.

- Madhuri Desai (2007). Resurrecting Banaras: Urban Space, Architecture and Religious Boundaries. ISBN 978-0-549-52839-5.

- Hügel, Baron (1845) 2000. Travels in Kashmir and the Panjab, containing a Particular Account of the Government and Character of the Sikhs, tr. Major T. B. Jervis. rpt, Delhi: Low Price Publications, p. 151

- Masson, Charles. 1842. Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, 3 v. London: Richard Bentley (1) 37

- Chitralekha, Zutshi (2019). "Kashmir as Mulk". Kashmir. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190990466.

- Polk, William Roe (2018). Crusade and Jihad: The Thousand-year War Between the Muslim World and the Global North. Yale University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0300222906.

- Bray, John (2008). Modern Ladakh: Anthropological Perspectives on Continuity and Change. Brill. p. 48. ISBN 978-9047443346.

- Dollfus, Pascale (1995). "The History of Muslims in Central Ladakh". The Tibet Journal. 20 (3): 41. ISSN 0970-5368. JSTOR 43300542.

- Ziad, Waleed (2021). Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints Beyond the Oxus and Indus. Harvard University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-674-24881-6.

- Chida-Razvi, Mehreen (2020). The Friday Mosque in the City: Liminality, Ritual, and Politics. Intellect Books. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-1-78938-304-1.

In addition to the masjid's use as a site for military storage, stables for the cavalry horses, and barracks for soldiers, parts of it were also used as storage for powder magazines.

- Miller, Yvette Alt (3 September 2023). "When Jews Found Refuge in the Sikh Empire". Aish. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- Tahir, Saif (3 March 2016). "The lost Jewish history of Rawalpindi, Pakistan". blogs.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

The history of Jews in Rawalpindi dates back to 1839 when many Jewish families from Mashhad fled to save themselves from the persecutions and settled in various parts of subcontinent including Peshawar and Rawalpindi.

- Considine, Craig (2017). Islam, race, and pluralism in the Pakistani diaspora. Milton: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-46276-9. OCLC 993691884.

- Khan, Naveed Aman (12 May 2018). "Pakistani Jews and PTI". Daily Times. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- "Rawalpindi – Rawalpindi Development Authority". Rawalpindi Development Authority (rda.gop.pk). Retrieved 27 February 2023.

Jews first arrived in Rawalpindi's Babu Mohallah neighbourhood from Mashhad, Persia in 1839, in order to flee from anti-Jewish laws instituted by the Qajar dynasty.

- Daiya, Kavita (2008). Violent belongings : partition, gender, and national culture in postcolonial India. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-59213-745-9. OCLC 302391286.

- Kumar, Ram Narayan (1991). The Sikh struggle : origin, evolution, and present phase. Georg Sieberer. Delhi: Chanakya Publications. p. 100. ISBN 81-7001-083-7. OCLC 24339822.

- Puri, Harish K. (June–July 2003). "Scheduled Castes in Sikh Community: A Historical Perspective". Economic and Political Weekly. Economic and Political Weekly. 38 (26): 2693–2701. JSTOR 4413731.

- J. S. Grewal (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. II.3. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0521637640.

- Hans, Surjit (April 2006). "Why are we sentimental about Ranjit Singh ?". The Panjab, Past and Present. XXXVII–Part 1: 47.

- Singh, Amarinder (2010). The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbar. Roli Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-81-7436-779-2.

- Cunningham, Joseph Davey (1849). A History of the Sikhs, from the Origin of the Nation to the Battles of the Sutlej. London: J. Murray. p. 424.

- https://www.rajasthali.marudharacollege.ac.in/papers/Volume-1/Issue-4/04-07.pdf

- Ranjit Singh: administration and British policy, (Prakash, pp. 31–33)

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the last to lay arms, (Duggal, pp. 136–137)

- Miniature painting from the photo album of princely families in the Sikh and Rajput territories by Colonel James Skinner (1778–1841)

Sources

- Chaurasia, R. S. (2004). History of the Marathas. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-8126903948. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Heath, Ian (2005), The Sikh Army 1799–1849, Osprey Publishing (UK), ISBN 1-84176-777-8

- Kalsi, Sewa Singh (2005), Sikhism, Religions of the World, Chelsea House Publications, ISBN 978-0-7910-8098-6

- Markovits, Claude (2004), A history of modern India, 1480–1950, London: Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2

- Jestice, Phyllis G. (2004), Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-355-1

- Johar, Surinder Singh (1975), Guru Tegh Bahadur, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for South Asian Studies, ISBN 81-7017-030-3

- Singh, Pritam (2008), Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy, Routledge, pp. 25–26, ISBN 978-0-415-45666-1

- Nesbitt, Eleanor (2005), Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, US, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-280601-7

- Waheeduddin, Fakir Syed (1981). The Real Ranjit Singh. Patiala, Punjab, India: Punjabi University. ISBN 978-8173807787. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

Further reading

- Grewal, J. S. (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. II.3 (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–127. ISBN 978-1316025338. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Volume 2: Evolution of Sikh Confederacies (1708–1769), By Hari Ram Gupta. (Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. 1999, ISBN 81-215-0540-2, 383 pages, illustrated)

- The Sikh Army (1799–1849) (Men-at-arms), By Ian Heath. (2005, ISBN 1-84176-777-8)

- The Heritage of the Sikhs By Harbans Singh. (1994, ISBN 81-7304-064-8).

- Sikh Domination of the Mughal Empire. (2000, 2nd ed. ISBN 81-215-0213-6)

- The Sikh Commonwealth or Rise and Fall of Sikh Misls. (2001, revised ed. ISBN 81-215-0165-2)

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lord of the Five Rivers, By Jean-Marie Lafont. (Oxford University Press. 2002, ISBN 0-19-566111-7)

- History of Panjab, By Dr L. M. Joshi and Dr Fauja Singh

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his Times, By Bhagat Singh. (Sehgal Publishers Service. 1990, ISBN 81-85477-01-9)

- Ranjit Singh – monarch mystique, By V. Nalwa. (Hari Singh Nalwa Foundation Trust. 2022, ISBN 978-81-910526-1-9)