Sindhis

Sindhis (Sindhi: سنڌي (Perso-Arabic); सिन्धी (Devanagari); /ˈsɪndiːz/[16] sˈɪndhiː, romanised as sin-dhee) are an Indo-Aryan[16] ethnolinguistic group who speak the Sindhi language and are native to the Sindh province of Pakistan. The historical homeland of Sindhis is bordered by the southeastern part of Balochistan, the Bahawalpur region of Punjab and the Kutch region of Gujarat.[17][18] Having been isolated throughout history unlike its neighbours, Sindhi culture has preserved its own uniqueness.[19][20]

| |

|---|---|

Sindhi Women in Traditional Libas with Peshani Patti on head | |

| Total population | |

| c. 37 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 34,252,262[1][2] | |

| 2,772,364[3][4][5][lower-alpha 1] | |

| 180,980 | |

| 94,620[6] | |

| 51,015[7] | |

| 38,760[8] | |

| 15,000 | |

| 20,000[9] | |

| 15,000 | |

| 12,065[10] | |

| 11,860[12] | |

| 3,300 | |

| 2,635[13] | |

| 1,000 | |

| 700 | |

| 500[14] | |

| Languages | |

| Sindhi English, Hindi–Urdu (Sanskrit/Arabic as liturgical languages) and numerous other languages widely spoken within the Sindhi diaspora | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Minority:

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gujaratis, Punjabis, Rajasthanis, Balochis | |

After the partition of British India in 1947, many Sindhi Hindus and Sindhi Sikhs migrated to the newly independent Dominion of India and other parts of the world; some Sindhis fled and formed diasporas settling around countries like England[21] and United States. Pakistani Sindhis are predominantly Muslim with a smaller Sikh and Hindu minority that are concentrated mostly in the eastern Sindh, whereas Indian Sindhis are predominantly Hindu with a sizeable Sikh, Jain and Muslim minority. Despite being geographically separated, Sindhis still maintain strong ties to each other and share similar cultural values and practices.[22][23]

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

Sindh portal |

Etymology

The name Sindhi is derived from the Sanskrit Sindhu which translates as "river" or "sea body" and Greeks used to call it "Indos"[24] which are names given to the Indus River and the surrounding region, which is where Sindhi is spoken.

The historical spelling "Sind" (from the Perso-Arabic سند) was discontinued in 1988 by an amendment passed in the Sindh Assembly, and is now spelt "Sindh." Hence, the term "Sindhi" was also introduced to replace "Sindi".

In the Balochi language, the traditional terms for Sindhis are Jadgal and Jamote. They are derived from the prefix Jatt referring to the tribe by that name, and the suffix gal meaning "speech". Thus, it signifies someone who speaks the language of the Jatts, i.e. a Jatt. The term Jatt historically encompassed Sindhis and Punjabis, and was frequently used by the British for Sindhis in their census records.[25][26]

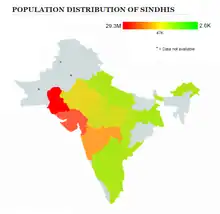

Geographic distribution

Sindh has been an ethnic historical region in Northwestern India, unlike its neighbors Sindh did not experience violent invasions,[27] Boundaries of various Kingdoms and rules in Sindh were defined on ethnic lines. Throughout history the geographical definition for Sindh referred to the south of Indus and its neighboring regions.[28]

Pakistan

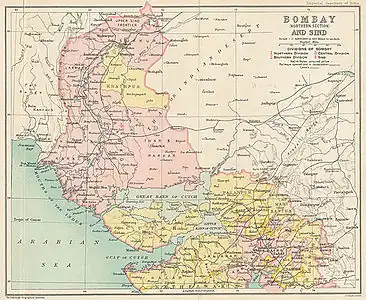

Afterwards the British conquest, Sindh was integrated into the Bombay province and the Khairpur state remained a British suzerain and Sindhis had almost no representation in the government of Bombay State to the point that only after 1890 was Sindh represented for the first time with only four members representing Sindh however this didn't satisfied Sindhis and soon a movement began for a separate province that resulted in the formation of Sind province in 1936 this was also supported by Muslim League which saw it necessary for the creation of Pakistan in future. Sindhis had contributed massively[29] to Pakistan movement specially by passing Muslim state resolution in Sindh assembly on 10 October 1938 under the condition for a self-government[30] under leaderships of GM Syed and Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, by this Sindh became the first province of British India to openly support a Muslim state in India and later Pakistan and its creation. Despite all of this the movement faced fierce political resistance from Sindhi nationalists such as Allah Bux Soomro and the Indian congress which were against Sindh joining Pakistan.[31]

After the breakup of Pakistan in 1971, G. M. Syed and other nationalists inspired by Bengali nationalism launched Jeay Sindh Movement[32] which aimed for autonomy initially but later on had separatist demands.[33] This movement reached its peak following assassination of Benazir Bhutto in 2007, starting from 2008 and lasting till 2012 till the death of Bashir Khan Qureshi.[34]

In Pakistan as per 2017 census,[35] Sindhis are the 3rd largest ethnic group below Pashtuns and followed by Saraikis, Sindhis account for 14% of Pakistan's population with estimated 34,250,000 people. Sufism has been an important aspect in the spiritual life of Muslim Sindhis as a result Sufism has become a marker of identity in Sindh.[36][37] Sindhis in Pakistan have province for them, Sindh, It also has the largest population of Hindus in Pakistan with 93% of Hindus in Sindh and rest are in other provinces.[38][39]

India

Sindhi Hindus were an economically prosperous community in urban Sindh before partition[40] but due to fear of persecution on the basis of religion and after large scale arrival of Muslim refugees from India,[41] they migrated to India after partition. They had a hard time[42][43] in India developing their economic status with no native homeland to permanently stay they had to live in states that had similarity with Sindhi culture[44] Despite all of that they were successful in establishing themselves as one of India's richest communities[45][46] especially through business and trade,[47][48][49] Which have helped India,[50] from famous actors like Ranveer Singh to Veteran politicians like L. K. Advani, all had families that came from Sindh.

In India as per 2011 census,[51] Sindhis have an estimated population of 2,770,000. Unlike Sindhis in Pakistan, Indian Sindhis are scattered throughout India in states like Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan.

| State | Population (100 Thousands) | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Gujarat | 11.84 | 42.7% |

| Maharashtra | 7.24 | 26.1% |

| Rajasthan | 3.87 | 13.9% |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2.45 | 8.8% |

| Chhattisgarh | 0.93 | 3.4% |

| Delhi | 0.31 | 1.1% |

| Uttar Pradesh | 0.29 | 1.0% |

| Assam | 0.20 | 0.7% |

| Karnataka | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| Andhra Pradesh | 0.11 | 0.4% |

Diaspora

Today many Sindhis exist outside the countries of Pakistan and India, particularly in Afghanistan where there are estimated 25,000 of them living, they came there due to merchant trade,[52] however during the crackdown on separatist groups by Pervez Musharraf an estimated 400-500 Sindhi separatists along with Baloch, fled to Afghanistan.[53]

Another groups of Sindhis came to the island of Ceylon which is the now modern day country of Sri Lanka estimated two centuries ago in hopes for business and trade.[54] and they came via migration from Hyderabad city of Sindh.[55] most came to Sri Lanka due to business.[56][57] However, after partition this trend increased as Sindhi Hindus left their home province.[58] Today they are mainly concentrated around Colombo.[59]

An urban rich community of Sindhis can be found in both Hong Kong[60] and Singapore.[61]

History

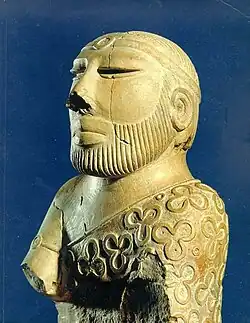

Sindh was the site of one of the Cradle of civilizations, the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation that flourished from about 3000 B.C. The Indo-Aryan tribes of Sindh gave rise to the Iron Age vedic civilization, which lasted till 500 BC. During this era, the Vedas were composed. In 518 BC, the Achaemenid empire conquered Indus valley and established Hindush satrapy in Sindh. Following Alexander the Great's invasion, Sindh became part of the Mauryan Empire. After its decline, Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians ruled in Sindh. Sindh is sometimes referred to as the Bab-ul Islam (transl. 'Gateway of Islam'), as it was one of the first regions of the Indian subcontinent to fall under Islamic rule. Parts of the modern-day province were intermittently subject to raids by the Rashidun army during the early Muslim conquests, but the region did not fall under Muslim rule until the Arab invasion of Sind occurred under the Umayyad Caliphate, headed by Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE. Afterwards, Sindh was ruled by a series of dynasties including Habbaris, Soomras, Sammas, Arghuns and Tarkhans. The Mughal empire conquered Sindh in 1591 and organized it as Subah of Thatta, the first-level imperial division. Sindh again became independent under Kalhora dynasty. The British conquered Sindh in 1843 AD after Battle of Hyderabad from the Talpur dynasty. Sindh became separate province in 1936, and after independence became part of Pakistan.

Prehistoric period

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus civilisation or Harappan culture, with features such as standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems.[62] It was one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Caral-Supe. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.[63] The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.[64]

The cities of the ancient Indus were noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, clusters of large non-residential buildings, and techniques of handicraft and metallurgy.[lower-alpha 2] Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals,[66] and the civilisation may have contained between one and five million individuals during its florescence.[67] A gradual drying of the region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial stimulus for its urbanisation. Eventually it also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise and to disperse its population to the east.

Historical period

For several centuries in the first millennium B.C. and in the first five centuries of the first millennium A.D., western portions of Sindh, the regions on the western flank of the Indus river, were intermittently under Persian,[68] Greek[69] and Kushan rule,[70] first during the Achaemenid dynasty (500–300 BC) during which it made up part of the easternmost satrapies, then, by Alexander the Great, followed by the Indo-Greeks[71] and still later under the Indo-Sassanids, as well as Kushans,[72] before the Islamic conquest between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. Alexander the Great marched through Punjab and Sindh, down the Indus river, after his conquest of the Persian Empire.

The Ror dynasty was a power from the Indian subcontinent that ruled modern-day Sindh and Northwest India from 450 BC to 489 AD.[73]

Medieval period

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Arab expansion towards the east reached the Sindh region beyond Persia. An initial expedition in the region launched because of the Sindhi pirate attacks on Arabs in 711–12, failed.[74][75]

In 712, when Mohammed Bin Qasim invaded Sindh with 8000 cavalry while also receiving reinforcements, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf instructed him not to spare anyone in Debal. The historian al-Baladhuri stated that after conquest of Debal, Qasim kept slaughtering its inhabitants for three days. The custodians of the Buddhist stupa were killed and the temple was destroyed. Qasim gave a quarter of the city to Muslims and built a mosque there.[76] According to the Chach Nama, after the Arabs scaled Debal's walls, the besieged denizens opened the gates and pleaded for mercy but Qasim stated he had no orders to spare anyone. No mercy was shown and the inhabitants were accordingly thus slaughtered for three days, with its temple desecrated and 700 women taking shelter there enslaved. At Ror, 6000 fighting men were massacred with their families enslaved. The massacre at Brahamanabad has various accounts of 6,000 to 26,000 inhabitants slaughtered.[77]

In the late 16th century, Sindh was brought into the Mughal Empire by Akbar, himself born in the Rajputana kingdom in Umerkot in Sindh.[78][79] Mughal rule from their provincial capital of Thatta was to last in lower Sindh until the early 18th century, while upper Sindh was ruled by the indigenous Kalhora dynasty holding power, consolidating their rule until the mid-18th century, when the Persian sacking of the Mughal throne in Delhi allowed them to grab the rest of Sindh. It is during this the era that the famous Sindhi Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai composed his classic Sindhi text Shah Jo Risalo[80][81][82]

_helmet%252C_1700s%252C_Kalhoro_Period.jpg.webp)

The Talpur dynasty (Sindhi: ٽالپردور) succeeded the Kalhoras in 1783 and four branches of the dynasty were established.[83] One ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. They were ethnically Baloch,[84] and for most of their rule, they were subordinate to the Durrani Empire and were forced to pay tribute to them.[85][86]

They ruled from 1783 until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.[87] The northern Khairpur branch of the Talpur dynasty, however, continued to maintain a degree of sovereignty during British rule as the princely state of Khairpur,[84] whose ruler elected to join the new Dominion of Pakistan in October 1947 as an autonomous region, before being fully amalgamated into West Pakistan in 1955.

Sindh was one of the earliest regions to be conquered by the Arabs and influenced by Islam[88] after 720 AD. Before this period, it was heavily Hindu and Buddhist. After 632 AD, it was part of the Islamic empires of the Abbasids and Umayyids. Habbari, Soomra, Samma, Kalhora dynasties ruled Sindh.

Baloch migrations in the region between 14th and 18th centuries and many Baloch dynasties saw a high Iranic mixture into Sindhis.[89][90][91]

British rule

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin),[92] which was later turned into a pun known as "Forgive me for I have Sindh".

The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[93][94]

The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. The distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time to time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[93][95]

Post-colonial era

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution,[96] rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.[97][98]

Demographics

Ethnicity and religion

The two main tribes of Sindh are the Soomro—descendants of the Soomra dynasty, who ruled Sindh during 970–1351 AD—and the Samma—descendants of the Samma dynasty, who ruled Sindh during 1351–1521 AD. These tribes belong to the same bloodline. Among other Sindhi Rajputs are the Bhuttos, Kambohs, Bhattis, Bhanbhros, Mahendros, Buriros, Bhachos, Chohans, Lakha, Sahetas, Lohanas, Mohano, Dahars, Indhar, Chhachhar/Chachar, Dhareja, Rathores, Dakhan, Langah, Junejo, Mahars, etc. One of the oldest Sindhi tribe is the Charan.[99] The Sindhi-Sipahi of Rajasthan and the Sandhai Muslims of Gujarat are communities of Sindhi Rajputs settled in India. Closely related to the Sindhi Rajputs are the Jats of Sindh, who are found mainly in the Indus delta region. However, tribes are of little importance in Sindh as compared to in Punjab and Balochistan. Identity in Sindh is mostly based on a common ethnicity.[100]

Islam in Sindh has a long history, starting with the capture of Sindh by Muhammad Bin Qasim in 712 CE. Over time, the majority of the population in Sindh converted to Islam, especially in rural areas. Today, Muslims make up over 90% of the population, and are more dominant in urban than rural areas. Islam in Sindh has a strong Sufi ethos with numerous Muslim saints and mystics, such as the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, having lived in Sindh historically. One popular legend which highlights the strong Sufi presence in Sindh is that 125,000 Sufi saints and mystics are buried on Makli Hill near Thatta.[101] The development of Sufism in Sindh was similar to the development of Sufism in other parts of the Muslim world. In the 16th century two Sufi tareeqat (orders)—Qadria and Naqshbandia—were introduced in Sindh.[102] Sufism continues to play an important role in the daily lives of Sindhis.[103]

Sindh also has Pakistan's highest percentage of Hindu overall, which accounts 8.7% of the population, roughly around 4.2 million people,[104] and 13.3% of the province's rural population as per 2017 Pakistani census report. These numbers also include the scheduled caste population, which stands at 1.7% of the total in Sindh (or 3.1% in rural areas),[105] and is believed to have been under-reported, with some community members instead counted under the main Hindu category.[106] Although, Pakistan Hindu Council claimed that there are 6,842,526 Hindus living in Sindh Province covering around 14.29% of the region's population.[107] Umerkot district in the Thar Desert is Pakistan's only Hindu-majority district. The Shri Ramapir Temple in Tandoallahyar whose annual festival is the second largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan is in Sindh.[108] Sindh is also the only province in Pakistan to have a separate law for governing Hindu marriages.[109]

Per community estimates, there are approximately 10,000 Sikhs in Sindh.[110]

Sindhi Hindus

Hinduism along with Buddhism was the predominant religion in Sindh before the Arab Islamic conquest.[111] The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who visited the region in the years 630–644, said that Buddhism was declining in the region.[112] While Buddhism declined and ultimately disappeared after Arab conquest mainly due to conversion of almost all of the Buddhist population of Sindh to Islam, Hinduism managed to survive through the Muslim rule until before the partition of India as a significant minority. Derryl Maclean explains what he calls "the persistence of Hinduism" on the basis of "the radical dissimilarity between the socio-economic bases of Hinduism and Buddhism in Sind": Buddhism in this region was mainly urban and mercantile while Hinduism was rural and non-mercantile, thus the Arabs, themselves urban and mercantile, attracted and converted the Buddhist classes, but for the rural and non-mercantile parts, only interested by the taxes, they promoted a more decentralized authority and appointed Brahmins for the task, who often just continued the roles they had in the previous Hindu rule.[111]

According to the 2017 Census of Pakistan, Hindus constituted about 8.7% of the total population of Sindh province, roughly around 4.2 million people.[113][114][104][115] Most of them live in urban areas such as Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur and Mirpur Khas. Hyderabad is currenyly the largest centre of Sindhi Hindus in Pakistan, with 100,000–150,000 living there.[113] The ratio of Hindus in Sindh was higher before the Partition of India in 1947.[116]

Prior to the Partition of India, around 73% of the population of Sindh was Muslim with almost 26% of the remaining being Hindu.[117][118]

Hindus in Sindh were concentrated in the urban areas before the Partition of India in 1947, during which most migrated to modern-day India according to Ahmad Hassan Dani. In the urban centres of Sindh, Hindus formed the majority of the population before the partition. The cities and towns of Sindh were dominated by the Hindus. In 1941, Hindus were 64% of the total urban population.[119] According to the 1941 Census of India, Hindus formed around 74% of the population of Hyderabad, 70% of Sukkur, 65% of Shikarpur and about half of Karachi.[120] By the 1951 Census of Pakistan, all of these cities had virtually been emptied of their Hindu population as a result of the partition.[121]

Hindus were also spread over the rural areas of Sindh province. Thari (a dialect of Sindhi) is spoken in Sindh in Pakistan and Rajasthan in India.

Religion in Sindh according to 2017 census

Sindhi Muslims

The connection between Sindh and Islam was established by the initial Muslim missions. According to Derryl N. Maclean, a link between Sindh and Muslims during the Caliphate of Ali can be traced to Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, a companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, who traveled across Sind to Makran in the year 649 AD and presented a report on the area to the Caliph. He supported Ali, and died in the Battle of the Camel alongside Sindhi Jats.[122] He was also a poet and few couplets of his poem in praise of Ali ibn Abu Talib have survived, as reported in Chachnama:[123]

ليس الرزيه بالدينار نفقدة

ان الرزيه فقد العلم والحكم

وأن أشرف من اودي الزمان به

أهل العفاف و أهل الجود والكريم [124]

"Oh Ali, owing to your alliance (with the prophet) you are true of high birth, and your example is great, and you are wise and excellent, and your advent has made your age an age of generosity and kindness and brotherly love".[125]

During the reign of Ali, many Jats came under the influence of Islam.[126] Harith ibn Murrah Al-abdi and Sayfi ibn Fil' al-Shaybani, both officers of Ali's army, attacked Sindhi bandits and chased them to Al-Qiqan (present-day Quetta) in the year 658.[127] Sayfi was one of the seven partisans of Ali who were beheaded alongside Hujr ibn Adi al-Kindi[128] in 660 AD, near Damascus.

In 712 AD, Sindh was incorporated into the Caliphate, the Islamic Empire, and became the "Arabian gateway" into India (later to become known as Bab-ul-Islam, the gate of Islam).

Sindh produced many Muslim scholars early on, "men whose influence extended to Iraq where the people thought highly of their learning", in particular in hadith,[129] with the likes of poet Abu al- 'Ata Sindhi (d. 159) or hadith and fiqh scholar Abu Mashar Sindhi (d. 160), among many others, and they're also those who translated scientific texts from Sanskrit into Arabic, for instance, the Zij al-Sindhind in astronomy.[130]

The majority of Muslim Sindhis follow the Sunni Hanafi fiqh with a minority being Shia Ithna 'ashariyah. Sufism has left a deep impact on Sindhi Muslims and this is visible through the numerous Sufi shrines which dot the landscape of Sindh.

Sindhi Muslim culture is highly influenced by Sufi doctrines and principles.[131] Some of the popular cultural icons are Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Jhulelal and Sachal Sarmast.

Tribes

Major tribes in Sindh include Soomros,[132] Sammas,[133][134] Kalhoras,[135] Bhuttos[136] and Rajper,[134] all of these tribes have significant influence in Sindh.

Hindu Sindhi castes

(1911 Census of British India)[137]

| Religion | Caste | Surnames[138][139] |

|---|---|---|

| Muslim | Rajput/ Jats/ Sammat | Soomros, Samo, Kalhora, Bhutto, Rajper, Kambohs, Bhati, Bhanbhros, Detho, Mahendros, Buriros, Unar, Dahri, Bhachos, Chohans, Lakha, Sahetas, Lohanas, Kaka, Mohano, Dahars, Indhar, Dakhan, Langah, Mahar, Chhachhar, Chachar, Halo, Dhareja, Juneja, Panhwar, Rathores, Memon, Khatri, Mahesar, Thaheem, Palh, Warya, Abro, Thebo, Siyal, Khaskheli, Palijo, Kehar, Solangi, Joyo, Burfat, Ruk, Palari, Jokhio, Jakhro, Noonari, Narejo, Samejo, Korejo, Shaikh, Naich, Sahu/Soho, Jutt, Mirjat, Khuhro, Bhangar, Roonjha, Rajar, Dahri, Mangi, Tunio, Gaho, Ghanghro, Chhutto, Hingoro, Hingorjo, Dayo, Halaypotro, Phulpotro, Pahore, Shoro, Arisar, Rahu, Rahujo, Katpar, Pechuho, Bhayo, Odho, Otho, Larak, Mangrio, Bhurt, Bughio, Chang, Chand, Chanar, Hakro, Khokhar. |

| Hindu/Muslim | Sindhi Bhaiband Lohana | Aishani, Agahni, Aneja, Anandani, Ambwani, Asija, Bablani, Bajaj, Bhagwani, Bhaglani, Bhojwani, Bhagnani, Balani, Baharwani, Biyani, Bodhani, Channa, Chothani, Dalwani, Damani, Dhingria, Dolani, Dudeja, Gajwani, Gangwani, Ganglani, Gulrajani, Hiranandani, Hotwani, Harwani, Jagwani, Jamtani, Jobanputra, Jumani, Kateja, Kodwani, Khabrani, Khanchandani, Khushalani, Lakhani, Lanjwani, Longan, Lachhwani, Ludhwani, Lulia, Lokwani, Manghnani, Mamtani, Mirani, Mirpuri, Mirwani, Mohinani, Mulchandani, Nihalani, Nankani, Nathani, Parwani, Phull, Qaimkhani, Ratlani, Rajpal, Rustamani, Ruprela, Sambhavani, Santdasani, Soneji, Setia, Sewani, Tejwani, Tilokani, Tirthani, Wassan, Vangani, Varlani,Vishnani, Visrani, Virwani and Valbani |

| Sindhi Amil Lohana | Advani, Ahuja, Ajwani, Bathija, Bhambhani, Bhavnani, Bijlani, Chhablani, Chhabria, Chugani, Dadlani, Daryani, Dudani, Essarani, [ [Gabrani] ]Gidwani, Hingorani, Idnani, Issrani, Jagtiani, Jhangiani, Kandharani, Karnani, Kewalramani, Khubchandani, Kriplani, Lalwani, Mahtani, Makhija, Malkani, Manghirmalani, Manglani, Manshani, Mansukhani, Mirchandani, Motwani, Mukhija, Panjwani, Punwani, Ramchandani,Raisinghani, Rijhsanghani, Sadarangani, Shahani, Shahukarani, Shivdasani, Sipahimalani (shortened to Sippy), Sitlani, Sarabhai, Singhania, Takthani, Thadani, Vaswani, Wadhwani Uttamsinghani. | |

| Muslim /Hindu | Artisan

Castes |

Kumbhar, Machhi, Mallah, Kori, Jogi, Drakhan, Mochi Labano/Chahwan, Patoli, Maganhar, Chaki. |

Emigration

The Sindhi diaspora is significant. Emigration from the Sindh became mainstream after the 19th century with the British conquest of Sindh. A number of Sindhi traders emigrated to the Canary Islands[140] and Gibraltar in this period.[141]

After the Partition of India, many Sindhi Hindus emigrated to Europe, especially to the United Kingdom,[142] North America, and Middle Eastern states such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Some settled in Hong Kong.[143][144][145]

Genetics

Sindhis exhibit high frequencies of allele-B cell, which shows similarities with those of Middle-East[146][147][148] having 87% Caucasoid admixture.[149] According to Lieutenant Burton an historical British Colonial officer, Sindhis were known for their strength and height as compared to other men in the region of Western India.[150]

Culture

Sindhi culture has its roots in the Indus Valley civilization.[91][151] Sindh has been shaped by the largely desert region, the natural resources it had available. The Indus or Sindhu River that passes through the land, and the Arabian Sea (that defines its borders) also supported the seafaring traditions among the local people. The local climate also reflects why the Sindhis have the language,[152] folklore, traditions, customs and lifestyle that are so different from the neighbouring regions. The Sindhi culture is also strongly practiced[153] by the Sindhi diaspora.

The roots of Sindhi culture go back to the distant past. Archaeological research during 19th and 20th centuries showed the roots of social life, religion and culture of the people of the Sindh:[154] their agricultural practices, traditional arts and crafts, customs and tradition and other parts of social life, going back to a mature Indus Valley Civilization of the third millennium BC.[155] Recent researches have traced the Indus valley civilization to even earlier ancestry.[156]

Language

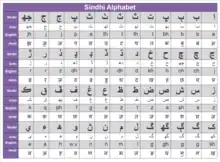

Sindhi[157] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by about 30 million people in the Pakistani province of Sindh, where it has official institutional status and has plans to being promoted further.[158] It is also spoken by a further 1.7 million people in India, where it is a scheduled language, without any state-level official status but despite that there have been online methods for teaching Sindhi.[159] The main writing system is the Perso-Arabic script, which accounts for the majority of the Sindhi literature and is the only one currently used in Pakistan. In India, both the Perso-Arabic script and Devanagari are used. At the occasion of 'Mother Language Day' in 2023, the Sindh Assembly passed a unanimous resolution to extend and increase the status of Sindhi as the national language[160][161][162]

Sindhi is believed to be originated from an older Indo-Aryan dialect spoken in Indus valley,[163] Sindhi has an attested history from the 10th century CE. Sindhi was one of the first Indo-Aryan languages to encounter influence from Persian and Arabic following the Umayyad conquest in 712 CE. A substantial body of Sindhi literature developed during the Medieval period, the most famous of which is the religious and mystic poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai from the 18th century. Modern Sindhi was promoted under British rule beginning in 1843, which led to the current status of the language in independent Pakistan after 1947.

| Sindhi alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب ٻ ڀ پ ت ٿ ٽ ٺ ث ج ڄ جهہ ڃ چ ڇ ح خ د ڌ ڏ ڊ ڍ ذ ر ڙ ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ڦ ق ڪ ک گ ڳ گهہ ڱ ل م ن ڻ و ھ ء ي |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

During British rule in India, a variant of the Persian alphabet was adopted for Sindhi in the 19th century. The script is used in Pakistan and India today. It has a total of 52 letters, augmenting the Persian with digraphs and eighteen new letters (ڄ ٺ ٽ ٿ ڀ ٻ ڙ ڍ ڊ ڏ ڌ ڇ ڃ ڦ ڻ ڱ ڳ ڪ) for sounds particular to Sindhi and other Indo-Aryan languages. Some letters that are distinguished in Arabic or Persian are homophones in Sindhi.

| جهہ | ڄ | ج | پ | ث | ٺ | ٽ | ٿ | ت | ڀ | ٻ | ب | ا |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɟʱ | ʄ | ɟ | p | s | ʈʰ | ʈ | tʰ | t | bʱ | ɓ | b | ɑː ʔ ∅ |

| ڙ | ر | ذ | ڍ | ڊ | ڏ | ڌ | د | خ | ح | ڇ | چ | ڃ |

| ɽ | r | z | ɖʱ | ɖ | ɗ | dʱ | d | x | h | cʰ | c | ɲ |

| ڪ | ق | ڦ | ف | غ | ع | ظ | ط | ض | ص | ش | س | ز |

| k | q | pʰ | f | ɣ | ɑː oː eː ʔ ∅ | z | t | z | s | ʂ | s | z |

| ي | ء | ه | و | ڻ | ن | م | ل | ڱ | گهہ | ڳ | گ | ک |

| j iː | ʔ ∅ | h | ʋ ʊ oː ɔː uː | ɳ | n | m | l | ŋ | ɡʱ | ɠ | ɡ | kʰ |

The name "Sindhi" is derived from the Sanskrit síndhu, the original name of the Indus River, along whose delta Sindhi is spoken.[164] Like other languages of the Indo-Aryan family, Sindhi is descended from Old Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit) via Middle Indo-Aryan (Pali, secondary Prakrits, and Apabhramsha). 20th century Western scholars such as George Abraham Grierson believed that Sindhi descended specifically from the Vrācaḍa dialect of Apabhramsha (described by Markandeya as being spoken in Sindhu-deśa, corresponding to modern Sindh) but later work has shown this to be unlikely.[165]

In Pakistan, Sindhi is the first language of 30.26 million people, or 14.6% of the country's population as of the 2017 census. 29.5 million of these are found in Sindh, where they account for 62% of the total population of the province. There are 0.56 million speakers in the province of Balochistan,[166] especially in the Kacchi Plain that encompasses the districts of Lasbela, Hub, Kachhi, Sibi, Usta Muhammad, Jafarabad, Jhal Magsi, Nasirabad and Sohbatpur.

In India, there were a total of 1.68 million speakers according to the 2011 census. The states with the largest numbers were Maharashtra (558,000), Rajasthan (354,000), Gujarat (321,000), and Madhya Pradesh (244,000).[167][lower-alpha 3]

Traditional dress

The traditional Sindhi clothing varies from tribe to tribe but most common are Lehenga Choli and Shalwar Cholo with Sindhi embroideries and mirror work for women and long veil is important, traditional dress for men is the Sindhi version of Shalwar Qameez/Kurta and Ajrak or Lungi (shawls) with either Sindhi Patko or Sindhi topi.[168] Ajrak[169] is added to dress for allure.

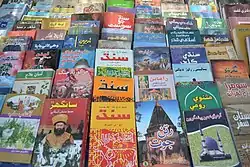

Literature

Sindhi language is ancient and rich in literature. Its writers have contributed extensively in various forms of literature in both poetry and prose. Sindhi literature is very rich,[170] and is one of the world's oldest literatures. The earliest reference to Sindhi literature is contained in the writings of Arab historians. It is established that Sindhi was the first eastern language into which the Quran was translated,[171][172][173] in the 8th or 9th century. There is evidence of Sindhi poets reciting their verses before the Muslim Caliphs in Baghdad. It is also recorded that treatises were written in Sindhi on astronomy, medicine and history during the 8th and 9th centuries.[174]

Sindhi literature, is the composition of oral and written scripts and texts in the Sindhi language in the form of prose: (romantic tales, and epic stores) and poetry: (Ghazal, Wai and Nazm). The Sindhi language is considered to be one of the oldest languages[175] of Ancient India, due to the influence on the language of Indus Valley inhabitants. Sindhi literature has developed over a thousand years.

According to the historians, Nabi Bux Baloch, Rasool Bux Palijo, and GM Syed, Sindhi had a great influence on the Hindi language in pre-Islamic times. Nevertheless, after the advent of Islam in eighth century, Arabic language and Persian language influenced the inhabitants of the area and were the official language of territory through different periods.

Music

Music from Sindh, is sung and is generally of 5 genres that originated in Sindh, The First one is the "Baits". The Baits style is vocal music in Sanhoon (low voice) or Graham (high voice). Second "Waee" instrumental music is performed in a variety of ways using a string instrument. Waee, also known as Kafi, other genres are Lada/Sehra/Geech, Dhammal, Doheera.[176] The sindhi folk musical instruments are Algozo, Tamburo, Chung, Yaktaro, Dholak, Khartal/Chapri/Dando, Sarangi, Surando, Benjo, Bansri, Borindo, Murli/Been, Gharo/Dilo, Tabla, Khamach/khamachi, Narr, Kanjhyun/Talyoon, Duhl Sharnai and Muto, Nagaro, Danburo, Ravanahatha.[177][178]

Dance

Dances of Sindh include the famous Ho Jamalo and Dhammal,.[179] Common dances include Jhumar/Jhumir (Different from Jhumar dance of South Punjab), Kafelo, Jhamelo however none of these have survived as much as Ho Jamalo.[180] In marriages and on other occasions, a special type of song is produced these are known as Ladas/Sehra/Geech and these are sung to celebrate the occasion of marriage, birth and on other special days, these are mostly performed by women.[179]

Some popular dances include:

- Jamalo: The notable Sindhi dance which is celebrated by Sindhis across the world.

- Jhumar/Jhumir: Performed on weddings and on special occasions.

- Dhamaal: is a mystical dance performed by Dervish.

- Chej,[181] Although Chej has seen decline in Sindh but it remains popular among Sindhi Hindus and diaspora.

- Bhagat: is a dance performed by professionals to entertain visiting people.

- Doka/Dandio: Dance performed using sticks.

- Charuri: Performed in thar.

- Muhana Dance: A dance performed by fishermen and fisherwomen of Sindh.

- Rasudo: Dance of nangarparker.

Folk tales

Sindhi folklore are folk traditions which have developed in Sindh over a number of centuries.[182][183] Sindh abounds with folklore, in all forms, and colours from such obvious manifestations as the traditional Watayo Faqir tales, the legend of Moriro, epic tale of Dodo Chanesar, to the heroic character of Marui which distinguishes it among the contemporary folklores of the region. The love story of Sassui, who pines for her lover Punhu, is known and sung in every Sindhi settlement. examples of the folklore of Sindh include the stories of Umar Marui and Suhuni Mehar. Sindhi folk singers and women play a vital role to transmit the Sindhi folklore. They sang the folktales of Sindh in songs with passion in every village of Sindh. Sindhi folklore has been compiled in a series of forty volumes under Sindhi Adabi Board's project of folklore and literature. This valuable project was accomplished by noted Sindhi scholar Nabi Bux Khan Baloch. folk tales like Dodo Chanesar,[184] Sassi Punnu,[183] Moomal Rano,[183][185] and Umar Marvi[183] are examples of Sindhi folk-talkes

The most famous Sindhi folk tales are known as the Seven Heroines of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, some notable tales include:

Festivals

Sindhis are very festive and like to organize festivals to commemorate their culture and heritage, most Sindhi celebrate the Sindhi Culture day which is celebrated regardless of religion to express their love for their culture.[186][187] It is observed with a great zeal.[188][189]

Muslim

Sindhi Muslims celebrate Islamic festivals such as Eid-ul-Adha and Eid al-Fitr which are celebrated with zeal and enthusiasm.[190] A festival known as Jashn-e-Larkana is also celebrated by Sindhi Muslims.[190]

Hindu

Compared to their Muslim counterparts, Hindu festivals are numerous and largely dependent on respective caste many Hindus have festivals based on a certain deity, common festivals include Cheti Chand (Sindhi new-year) Teejri, Thadri, Utraan.[191][192]

Cuisine

Sindhi cuisine has been influenced by Central Asian, Iranian, Mughal food traditions.[193] It is mostly a non-vegetarian cuisine,[193] with even Sindhi Hindus widely accepting of meat consumption.[194] The daily food in most Sindhi households consists of wheat-based flat-bread (mani/roti) and rice accompanied by two dishes, one gravy and one dry with curd, papad or pickle. Freshwater fish and a wide variety of vegetables are usually used in Sindhi cuisine.[195]

Restaurants specializing in Sindhi cuisine are rare, although it is found at truck stops in rural areas of Sindh province, and in a few restaurants in urban Sindh.[196]

The arrival of Islam within India influenced the local cuisine to a great degree. Since Muslims are forbidden to eat pork or consume alcohol and the Halal dietary guidelines are strictly observed, Muslim Sindhis focus on ingredients such as beef, lamb, chicken, fish, vegetables and traditional fruit and dairy. Hindu Sindhi cuisine is almost identical with the difference that beef is omitted. The influence of Central Asian, South Asian and Middle Eastern cuisine in Sindhi food is ubiquitous. Sindhi cuisine was also found in India, where many Sindhi Hindus migrated following the Partition of India in 1947. Before Independence, the State of Sindh was under Bombay Presidency.

Culture Day

Sindhi Cultural Day (Sindhi: سنڌي ثقافتي ڏھاڙو) is a popular Sindhi cultural festival. It is celebrated with traditional enthusiasm to highlight the centuries-old rich culture of Sindh. The day is celebrated each year in the first week of December on the Sunday.[197][198][199] It's widely celebrated all over Sindh, and amongst the Sindhi diaspora population around the world.[200][201] Sindhis celebrate this day to demonstrate the peaceful identity of Sindhi culture and acquire the attention of the world towards their rich heritage.[202]

On this jubilation people gather in all major cities of Sindh at press clubs, and other places to arrange various activities. Literary (poetic) gatherings, mach katchehri (gathering in a place and sitting round in a circle and the fire on sticks in the center), musical concerts, seminars, lecture programs and rallies.[203] Sindhi cultural day is celebrated worldwide on the first Sunday of December.[204] On the occasion people wearing Ajrak and Sindhi Topi, traditional block printed shawl the musical programs and rallies are held in many cities to mark the day with zeal. Major hallmarks of cities and towns are decorated with Sindhi Ajrak. People across Sindh exchange gifts of Ajrak and Topi at various ceremonies. Even the children and women dress up in Ajrak, assembling at the grand gathering, where famous Sindhi singers sing Sindhi songs, which depicts peace and love message of Sindh. The musical performances of the artists compel the participants to dance on Sindhi tunes and national song ‘Jeay Sindh Jeay-Sindh Wara Jean’.

All political, social and religious organizations of Sindh, besides the Sindh Culture Department and administrations of various schools, colleges and universities, organize variety of events including seminars, debates, folk music programs, drama and theatric performances, tableaus and literary sittings to mark this annual festivity.[205] Sindhi culture, history and heritage are highlighted at the events.[206]

Poetry

Prominent in Sindhi culture, continues an oral tradition dating back a thousand years. The verbal verses were based on folk tales. Sindhi is one of the major oldest languages of the Indus Valley having a peculiar literary colour both in poetry and prose. Sindhi poetry is very rich in thought as well as contain variety of genres like other developed languages. Poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Sachal Sarmast is very famous throughout Sindh. Since the 1940s, Sindhi poetry has incorporated broader influences including the sonnet and blank verse. Soon after the independence of Pakistan in 1947, these forms were reinforced by Triolet, Haiku, Renga and Tanka. At present, these forms continue to co-exist, albeit in a varying degree, with Azad Nazm having an edge over them all.

Notable people

.jpg.webp) Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, ninth prime minister of Pakistan

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, ninth prime minister of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari, ex-president of Pakistan

Asif Ali Zardari, ex-president of Pakistan Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Foreign Minister of Pakistan

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Foreign Minister of Pakistan Abdul Majid Bhurgri, Sindhi computer scientist

Abdul Majid Bhurgri, Sindhi computer scientist Fahad Mustafa, Sindhi actor in Lollywood

Fahad Mustafa, Sindhi actor in Lollywood Shah Abdul Latif Bhitati, Sindhi Sufi saint of 18th century

Shah Abdul Latif Bhitati, Sindhi Sufi saint of 18th century Abida Parveen, notable Sufi musician

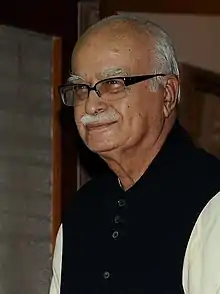

Abida Parveen, notable Sufi musician L. K. Advani, 7th deputy prime minister of India

L. K. Advani, 7th deputy prime minister of India Tarun Tahiliani, notable Indian fashion designer

Tarun Tahiliani, notable Indian fashion designer.jpeg.webp) Benazir Bhutto, 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan

Benazir Bhutto, 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan.jpg.webp) Gulu Lalvani, Indian Sindhi businessman

Gulu Lalvani, Indian Sindhi businessman Imdad Ali, Sindhi philosopher and educationist

Imdad Ali, Sindhi philosopher and educationist Sachal Sarmast, Sindhi legendary poet

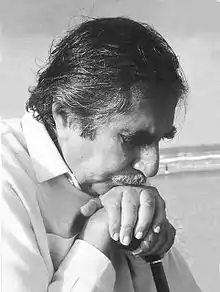

Sachal Sarmast, Sindhi legendary poet Shaikh Ayaz, Sindhi language poet

Shaikh Ayaz, Sindhi language poet Kumail Nanjiani, American Sindhi comedian and actor

Kumail Nanjiani, American Sindhi comedian and actor Sunil Vaswani, Indian billionaire businessman

Sunil Vaswani, Indian billionaire businessman_(cropped).jpg.webp) Hansika Motwani, Indian actress

Hansika Motwani, Indian actress Tamannah Bhatia, Indian actress

Tamannah Bhatia, Indian actress Pir Pagaro, the 8th Pir of Pagaro and leader of Grand Democratic Alliance

Pir Pagaro, the 8th Pir of Pagaro and leader of Grand Democratic Alliance_(cropped).jpg.webp) Ranveer Singh, Indian actor

Ranveer Singh, Indian actor

See also

- Cheti Chand

- Nanakpanthi

- Guru Nanak Jayanti

- Sindhudesh

- Sindhi nationalism

- Sindhis in India

- Hinduism in Sindh Province

- Sindhi Sikhs

- Sandhai Muslims

- List of Sindhi people

- Ulhasnagar

- Sindhi names

- Sindhi Pathan

- Sindhi Baloch

- Sindhi bhagat

- Sindhi Memon

- Sammat

- Sandhai Muslims

- Sindhi language media in Pakistan

- Sindhi-language media

- List of Sindhi-language newspapers

- Sindhi Language Authority

- Sindhi Adabi Board

- Sindhi Adabi Sangat

- Sindhi folk tales

- Sindhi folklore

- Sindhi music

- List of Sindhi singers

- Sindhi music videos

- Sindhi poetry

- Tomb paintings of Sindh

- List of Sindhi singers

- List of Sindhi festivals

- Sindhi culture

- Sindhi biryani

- Sindhi Camp

- Sindhi cap

- Sindhi Cultural Day

- Sindhi cinema

- Sindhi colony

- Sindhi cuisine

- Sindhi High School, Hebbal

- Romanisation of Sindhi

Notes

- Includes those who speak the Sindhi language and includes the 1 million Kutchi Speakers to. Ethnic Sindhis in India who no longer speak the language are not included in this number.

- These covered carnelian products, seal carving, work in copper, bronze, lead, and tin.[65]

- This is the number of people who identified their language as "Sindhi"; it does not include speakers of related languages, like Kutchi.

References

- "Pakistan". 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Pakistan's population is 207.68m, shows 2017 census result". 19 May 2021.

- "Now, class 6th & 8th students of U.P. Govt schools to learn about Sindhi deities, personalities". 23 May 2023.

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "How many Sindhis live in India? Part 2". 29 December 2019.

- http://www.ophrd.gov.pk/SiteImage/Downloads/Year-Book-2017-18.pdf Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- "UK Government Web Archive". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- "Explore Census Data". Archived from the original on 26 November 2020.

- "Sindhi Association Hong Kong". Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Sindhis". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Kesavapany, K.; Mani, A.; Ramasamy, P. (2008). Rising India and Indian Communities in East Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812307996. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "SBS Australian Census Explorer". www.sbs.com.au. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- "About | The Hindu Community of Gibraltar". Hindu Community Gib. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sindhis

- Butt, Rakhio (1998). Papers on Sindhi Language & Linguistics. Institute of Sindhology, University of Sindh. ISBN 9789694050508. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Siraj, Dr. Amjad. Sindhi Language. ISBN 978-969-625-082-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Faiz, Asma (9 December 2021). In Search of Lost Glory: Sindhi Nationalism in Pakistan. Hurst Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78738-632-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "Culture". www.wwf.org.pk. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali (2018). Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh. p. 17.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "The Sindh diaspora: India and the United Kingdom". UK Research and Innovation. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- David, Maya Khemlani; Abbasi, Muhammad Hassan Abbasi; Ali, Hina Muhammad (January 2022). Young Sindhi Muslims in Cultural Maintenance in the Face of Language Shift.

Despite a shift away from habitual use of Sindhi language, they have maintained their cultural values and norms.

- "Excerpt: For Some Sindhi Diaspora Members, Navigating Multiple Identities Is Not a Problem". The Wire. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- Sindhi Manual: Language and Culture (PDF).

- Westphal-Hellbusch, Sigrid; Westphal, Heinz (1986). The Jat of Pakistan. Lok Virsa. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Jahani, Carina; Korn, Agnes; Titus, Paul Brian (2008). The Baloch and Others: Linguistic, Historical and Socio-political Perspectives on Pluralism in Balochistan. Reichert Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89500-591-6. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Mahajan, V. D. (2007). History of Medieval India. S. Chand Publishing. ISBN 978-81-219-0364-6. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Sindh was isolated from the rest of India and consequently nobody took any interest in Sindh and the same was conquered by the Arabs.

- Pithawala, M. B. (2018). Historical Geography of Sindh (PDF). University of London: Sani Panhwar Publishers.

- "Sindh's role in Pakistan movement". DAWN.COM. 24 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- Riffat, Fatima; Chawla, Muhammad Iqbal; Tariq, Adnan (30 June 2016). "A History of Sindh from a Regional Perspective: Sindh and Making of Pakistan".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wangchuk, Rinchen Norbu (6 August 2018). "Allah Bux Soomro: The Sindhi Premier Who Fought The British & The Two-Nation Theory!". The Better India. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Paracha, Nadeem F. (10 September 2015). "Making of the Sindhi identity: From Shah Latif to GM Syed to Bhutto". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- Siddiqi, Farhan Hanif (4 May 2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-33696-6.

- Voices, Pingback: Looking Back at 2012 in South Asia-Part II · Global (7 April 2012). "Pakistan: Immediate Reactions on the Death of Sindhi Nationalist Leader". Global Voices. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Hasnain, Khalid (19 May 2021). "Pakistan's population is 207.68m, shows 2017 census result". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Levesque, Julien (2016). "Sindhis are Sufi by Nature": Sufism as a Marker of Identity in Sindh. HAL Open Science. pp. 212–227. ISBN 9781138910683.

- Harjani, Dayal N. (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals - Part 1. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Sindhi folklore, literature, poetry, music came to be influenced by Sufi ideologies to a great extent and therefore Sindhi psyche has been ingrained with piousness and the veneration of saints and visits to Dargahs

- "Hindus under the official Muslims of Pakistan". Daily Times. 17 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- Singh, Rajkumar (11 November 2019). "Religious profile of today's Pakistani Sindh Province". South Asia Journal. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- "RSS and Sindhi Hindus". Economic & Political Weekly. 41 (52). 30 December 2006. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- "Who orchestrated the exodus of Sindhi Hindus after Partition?". The Express Tribune. 4 June 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- "Shortchanged by Partition, why Sindhis hold Karachi especially dear". The Indian Express. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Ganesan, Nikita Puri and Ranjita (8 March 2019). "India's Sindhi community is flourishing but the going isn't always easy". www.business-standard.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Pioneer, The. "Scattered Sindhi society". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- "Most billionaires in India today once resided in Pakistan's Sindh". Daily Times. 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- "After Partition, Sindhis Turned Displacement Into Determination and Enterprise". The Wire. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Dogra, Palak (29 January 2023). "Why Are Gujaratis, Marwaris, Sindhis So Good At Making Money?". edtimes.in. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Service, Tribune News. "'The Sindhis — Selling Anything, Anywhere' is story of the quintessential Sindhi businessman". Tribuneindia News Service. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- "How Sindhis do Business, An Excerpt from 'Paiso'". Penguin Random House India. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Service, Statesman News (1 April 2023). "Bhagwat lauds contribution of Sindhis to the nation". The Statesman. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- "2011 Census of India". 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- "Hinduism in ancient and modern Afghanistan". Pakistantoday.com.pk. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "2009: Kabul admitted having 500 Baloch, Sindhi separatists in Afghanistan". Dawn.com. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Nazim, Aisha. "Why the Partition of India was a tectonic event for Sri Lankan Sindhis". Scroll.in. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- "The story of the Lankan Sindhis". Hindustan Times. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- "Proud of their heritage; proud to be Lankans". The Sunday Times Sri Lanka. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- India, Ministry External Affairs. "India-Sri Lanka Relations" (PDF). MEA.gov.in. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- Aggarwal, Saaz. "How did the Partition affect the people of Sindh? Using true stories, a new book finds out". Scroll.in. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- "Documenting Sri Lanka's Ethnic Minorities: The Other 2% - Roar Media". roar.media. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- "They made a life in Hong Kong: Hindus on India's partition". South China Morning Post. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Auto, Hermes (13 March 2022). "Sindhi community has contributed to Singapore: PM Lee | The Straits Times". www.straitstimes.com. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (10 July 2013). Land of the seven rivers : a brief history of India's geography. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-342093-4. OCLC 855957425.

- "Mohenjo-Daro: An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- "Mohenjo Daro: Could this ancient city be lost forever?". BBC News. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Wright 2009, pp. 115–125.

- Dyson 2018, p. 29 "Mohenjo-daro and Harappa may each have contained between 30,000 and 60,000 people (perhaps more in the former case). Water transport was crucial for the provisioning of these and other cities. That said, the vast majority of people lived in rural areas. At the height of the Indus valley civilization the subcontinent may have contained 4-6 million people."

- McIntosh 2008, p. 387: "The enormous potential of the greater Indus region offered scope for huge population increase; by the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Harappans are estimated to have numbered somewhere between 1 and 5 million, probably well below the region's carrying capacity."

- Sharar, Abdulhalim (1907). A History of Sindh: Volume I. Lucknow, India: Dilgudaz Press.

- Biagi, Paolo (2007). With Alexander in India and Central Asia: Moving East and Back to West (PDF). Malta: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-584-7.

- Dayal, N. Harjani (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals – Part 1. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - J.C, Aggarwal (2017). S. Chand's Simplified Course in Ancient Indian History. ISBN 978-81-219-1853-4. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1998 District Census Report of [name of District].: Sindh. 1999. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kessler, P L. "Kingdoms of South Asia – Kingdoms of the Indus / Sindh". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, p. 602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2, archived from the original on 12 March 2023, retrieved 25 February 2023

- "History of India". indiansaga.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Wink 2002, p. 203.

- The Classical age, by R. C. Majumdar, p. 456

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p.39. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663700. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- "Hispania [Publicaciones periódicas]. Volume 74, Number 3, September 1991 – Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". cervantesvirtual.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Brohī, ʻAlī Aḥmad (1998). The Temple of Sun God: Relics of the Past. Sangam Publications. p. 175. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

Kalhoras a local Sindhi tribe of Channa origin...

- Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1851). Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus. W. H. Allen. p. 410. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

Kalhoras ... were originally Channa Sindhis , and therefore converted Hindoos.

- Verkaaik, Oskar (2004). Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan. Princeton University Press. pp. 94, 99. ISBN 978-0-69111-709-6.

The area of the Hindu-built mansion Pakka Qila was built in 1768 by the Kalhora kings, a local dynasty of Arab origin that ruled Sindh independently from the decaying Moghul Empire beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.

- "History of Khairpur and the royal Talpurs of Sindh". Daily Times. 21 April 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Solomon, R. V.; Bond, J. W. (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Baloch, Inayatullah (1987). The Problem of "Greater Baluchistan": A Study of Baluch Nationalism. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden. p. 121. ISBN 9783515049993. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Ziad, Waleed (2021). Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints Beyond the Oxus and Indus. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780674248816. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- "The Royal Talpurs of Sindh – Historical Background". www.talpur.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH–18TH CENTURIES, presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 Archived 8 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Ahmed, Ashfaq (7 December 2021). "Indian and Pakistani Sindhi expats together celebrate Sindhi Cultural Day with fanfare in Dubai". Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Maher, Mahim (27 March 2014). "From Zardaris to Makranis: How the Baloch came to Sindh". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Sheikh, Muhammad Ali (2013). A Monograph on Sindh through centuries (PDF). SMI University Press Karachi.

- Ratcliffe, Susan (17 March 2011). Concise Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. ISBN 978-0-19-956707-2. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Long, Roger D.; Singh, Gurharpal; Samad, Yunas; Talbot, Ian (8 October 2015), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- Sodhar, Muhammad Qasim; Memon, Ghulam Rashid; Mahesar, Ghulam Akbar (July–December 2015). British annexation of Sindh: The Opium Economy Factor. Vol. 49. Grassroots Journal.

- Khera, P. N.; Khan, Shafaat Ahmed (1941). British Policy towards Sindh upto Annexation (PDF). India: Sani Panhwar Publishers.

- Bhavnani, Nandita (2014). The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. ISBN 978-93-84030-33-9. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kumar, Priya; Kothari, Rita (2016). "Sindh, 1947 and Beyond". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 39 (4): 776–777. doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752. S2CID 151354587.

- Aggarwal, Saaz (13 August 2022). "How refugees from Sindh rebuilt their lives – and India – after Partition". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Kamphorst, Janet (2008). In praise of death: history and poetry in medieval Marwar (South Asia). Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978-90-485-0603-3. OCLC 614596834. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- Abdullah, Ahmed. "The People and The Land of Sindh". Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2023 – via Scribd.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Pearls from Indus Jamshoro, Sindh, Pakistan: Sindhi Adabi Board (1986). See p. 150.

- "History of Sufism in Sindh discussed". DAWN.COM. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Can Sufism save Sindh?". DAWN.COM. 2 February 2015. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "SALIENT FEATURES OF FINAL RESULTS CENSUS-2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Religion in Pakistan (2017 Census)" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Scheduled castes have a separate box for them, but only if anybody knew". Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Hindu Population (PK)". Pakistanhinducouncil.org.pk. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Hindu's converge at Ramapir Mela near Karachi seeking divine help for their security - The Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Jatoi, Shahid (8 June 2017). "Sindh Hindu Marriage Act—relief or restraint?". Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Tunio, Hafeez (31 May 2020). "Shikarpur's Sikhs serve humanity beyond religion". The Express Tribune. Pakistan. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- MacLean, Derryl L. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. BRILL. pp. 12–14, 77–78. ISBN 978-90-040-8551-0.

- Shu Hikosaka, G. John Samuel, Can̲ārttanam Pārttacārati (ed.), Buddhist themes in modern Indian literature, Inst. of Asian Studies, 1992, p. 268

- "Pakistan Census Data" (PDF). Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "TABLE 9 - POPULATION BY SEX, RELIGION AND RURAL/URBAN" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- "Scheduled castes have a separate box for them, but only if anybody knew". Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Partition and the "other" Sindhi". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Mehtab Ali Shah (1997). The foreign policy of Pakistan: ethnic impacts on diplomacy, 1971–1994. London: I B Tauris and Co Ltd. p. 46.

- Rahimdad Khan Molai Shedai; Janet ul Sindh; 3rd edition, 1993; Sindhi Adbi Board, Jamshoro; page no: 2.

- Proceedings of the First Congress of Pakistan History & Culture held at the University of Islamabad, April 1973, Volume 1, University of Islamabad Press, 1975

- "INDIA – Part I – Tables" (PDF). Census of India 1941. p. 90. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- "Population According to Religion" (PDF). Census of Pakistan, 1951. p. 8,22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- M. Ishaq, "Hakim Bin Jabala – An Heroic Personality of Early Islam", Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, pp. 145–50, (April 1955).

- Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, BRILL, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- چچ نامہ، سندھی ادبی بورڈ، صفحہ 102، جامشورو، (2018)

- Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, "The Chachnama", p. 43, The Commissioner's Press, Karachi (1900).

- Ibn Athir, Vol. 3, pp. 45–46, 381, as cited in: S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- Ibn Sa'd, 8:346. The raid is noted by Baâdhurî, "fatooh al-Baldan" p. 432, and Ibn Khayyât, Ta'rîkh, 1:173, 183–84, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, BRILL, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- Tabarî, 2:129, 143, 147, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, Brill, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- Mazheruddin Siddiqui, "Muslim culture in Pakistan and India" in Kenneth W. Morgan, Islam, the Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1987, p. 299

- Ahmed Abdulla, The historical background of Pakistan and its people, Tanzeem Publishers, 1973, p. 109

- Ansari, Sarah FD. Sufi saints and state power: the pirs of Sind, 1843–1947. No. 50. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Siddiqui, Habibullah. The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule (PDF). p. 1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Panhwar, M. H. Historical Atlas of Soomra Kingdom of Sindh (PDF). p. 74.

- Lari, Suhail Zaheer. A History of Sindh (PDF). p. 42.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "History of Sindh". Government of Sindh. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- Taseer, Salman (3 September 1979). Bhutto a Political Biography (PDF). Sindh: Sani Panhwar Publishers. ISBN 9780903729482.

- "Census of India, 1911" (PDF).

- U.T Thakur (1959). Sindhi Culture.

- Ansari, Sheikh Sadik Ali Sher Ali (1901). The Musalman Races found in Sind, Baluchistan and Afghanistan.

- Kamalakaran, Ajay. "In the story of Sindhi migration, Canary Islands played a small but important role". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- Peck, James (2004). Hindus on a rock. p. 1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - David, Maya Khemlani (2001). The Sindhi Hindus of London. Malaysia: University of Malaya.

- "They made a life in Hong Kong: Hindus on India's partition". South China Morning Post. 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- "Homepage of Sindhi Association of Hongkong & China". sindhishongkong.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Roshni. "Hong Kong Sindhis: Living in a Bubble!". Roshni Write Now. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Papiha, Surinder Singh; Deka, Ranjan; Chakraborty, Ranajit (31 October 1999). Genomic Diversity: Applications in Human Population Genetics ; [proceedings of a Symposium on Molecular Anthropology in the Twenty-First Century, Held During the 14th International Congress of the Association of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, Held July 26 - August 1, 1998, in Williamsburg, Virginia]. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-306-46295-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Yasmin, Memona; Rakha, Allah; Noreen, Saadia; Salahuddin, Zeenat (1 May 2017). "Mitochondrial control region diversity in Sindhi ethnic group of Pakistan". Legal Medicine. 26: 11–13. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.02.001. ISSN 1344-6223. PMID 28549541.

- Adnan, Atif; Rakha, Allah; Nazir, Shahid; Rehman, Ziaur (September 2019). "Genetic characterization of 15 autosomal STRs in the Interior Sindhi Population of Pakistan and their phylogenetic relationship with other populations". ResearchGate: 5 – via International Journal of Immunogenetics.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei; Mittnik, Alissa; Bánffy, Eszter; Economou, Christos; Francken, Michael (2 March 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Sherring, Matthew A. (1879). Hindu Tribes and Castes: As Represented in Benares ; with Illustrations. p. 349.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Shaheen, Yussouf (2018). The Story Of The Ancient Indus People (PDF). Karachi, Sindh: Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh.

- Shahriar, Ambreen; Bughio, Faraz Ali (June 2014). Restraints of language and culture of Sindh: An historical perspective. Vol. 48. Grassroots Journal.

- "Love for Sindhi language brings together Indian and Pakistani expats in Dubai". gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- Dootio, Mazhar Ali (6 December 2018). "Sindhi culture and its importance". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Sharma, Ram Nath; Sharma, Rajendra K. (1997). Anthropology. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-673-0. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

The cultural marks of the Bronze Age are found in Baluchistan, Makran, Khurram, Jhalwan and Sindh

- Zhang, Sarah (5 September 2019). "A Burst of Clues to South Asians' Genetic Ancestry". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- "Pakistan: Sindh CM launches website aimed at digitising rare Sindhi language books". gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- "India's first Sindhi OTT App launch - SINDHIPLEX". ANI News. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- "Members decry delay in declaring Sindhi a national language". The Express Tribune. 21 February 2023. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Siddiqui, Tahir (22 February 2023). "Govt, opposition demand national language status for Sindhi". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Pakistan: Members of Sindh Assembly demand national language status for Sindhi". ANI News. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Allana, Ghulam Ali (2009). Sindhi Language and Literature at a Glance. p. 5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Sindhi". The Languages Gulper. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- Wadhwani, Y. K. (1981). "The Origin of the Sindhi Language" (PDF). Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. 40: 192–201. JSTOR 42931119. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Dawn. 28 May 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2022. The numbers have been calculate based on the percentages and the population totals. For example, the figure of 30.26 million is calculated from the reported 14.57% for the speakers of Sindhi and the 207.685 million total population of Pakistan.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. "C-16: Population by mother tongue, India - 2011". Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- Manian, Ranjini (9 February 2011). Doing Business in India For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-05163-4. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Gujarati, Marathi, Punjabi, and Sindhi. As far as dress is concerned, women in the north wear Sari and Shalwar Kameez, Chudidar-Kurta, and Lehenga-Kurta Men wear Pyjama-Kurta and Dhoti-Kurta

- Bilgrami, Noor Jehan (2000). Ajrak: Cloth from Soil of Sindh. University of Nebraska, United States of America: Textile Society of America.

- Meena, R. P. Art, Culture and Heritage of India: for Civil Services Examination. New Era Publication. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Sindhi literature is very rich and oldest literature in the world's literatures

- Rahman, Tariq (1999). The Teaching of Sindhi and Sindhi Ethnicity. p. 1.

Sindhi is one of the most ancient languages of India. Indeed, the first language Muslims (Arabs) came in contact with when they entered India in large numbers was Sindhi. Thus several Arab writers mention that Sindhi was the language of people in al-Mansura, the capital of Sind. Indeed, the Rajah of Alra called Mahraj, whose kingdom was situated between Kashmir and Punjab, requested Amir Abdullah bin Umar, the ruler of al-Mansura, to send him someone to translate the Quran into his language around A.D. 882. The language is called 'Hindi' by Arab historians (in this case the author of Ajaib ul Hind) who often failed to distinguish between the different languages of India and put them all under the generic name of 'Hindi'. However, Syed Salman Nadwi, who calls this the first translation of the Quran into any Indian language suggests that this language might be Sindhi.

- Anwar, Tauseef (29 December 2016). "Sindhi Culture". PakPedia. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Harjani, Dayal N. (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals - Part 1. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

They were the first Muslims to translate the Quran into the Sindhi language

- Sind Through the Centuries: An Introduction to Sind, a Progressive Province of Pakistan. Publicity and Publication Committee, Sind Through the Centuries Seminar. 1975. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

During the long period of history, Sindhi language has absorbed influences of the old Iranian language during, It is also recorded that treatises were written in Sindhi on Astronomy, Medicine

- Mukherjee, Sibasis (May 2020). "Sindhi Language and its History". ResearchGate. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- "Sindhi Music". Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- "Indigenous Sindhi Music Instruments". Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- "Sindhi music on the streets of Karachi". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "An Introduction To Sindhi Dance And Music". Sindhi Khazana. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2004). Essential Sindhi Culturebook. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-303201-4.

- "Sindhi Folk Dance Chhej - The Sindhu World Dance of Unity: Sindhi Group Dance: Cheti Chand: Bahrana: Jhulelal". thesindhuworld.com. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- Doctor, Roma (30 January 2012). Folklore: Sindhi Folklore, An Introductory Survey. p. 223. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1985.9716351.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Lalwani, Tamana (March 2018). Sindhi Folklore and Sindhi Folk Tales (PDF). India: Bharat College of Arts and Commerce.

- "The legend of Dodo Chanesar". The Express Tribune. 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Legendary Folk Tales of Sindh - Moomal Rano" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Three-day Sindhi Culture Day family festival kicks off". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindhi Cultural Day". The Nation. 23 December 2022. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindh Cultural Day being celebrated today across Pakistan". Daily Pakistan Global. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.