Maritime history of Somalia

Maritime history of Somalia refers to the seafaring tradition of the Somali people.[1] It includes various stages of Somali navigational technology, shipbuilding and design, as well as the history of the Somali port cities. It also covers the historical sea routes taken by Somali sailors which sustained the commercial enterprises of the historical Somali kingdoms and empires, in addition to the contemporary maritime culture of Somalia.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

In antiquity, the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh and spices, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans and Babylonians.[2][3] During the classical era, several ancient city-states such as Ophir at the time Berbera and Ras Hafun and Hiran then part of Mogadishu competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade also flourished in Somalia.[4] In the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuran Sultanate, the latter of which maintained profitable maritime contacts with Arabia, India, Venetia,[5] Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. This tradition of seaborne trade was maintained in the early modern period, with Berbera being the pre-eminent Somali port during the 18th–19th centuries.[6]

Antiquity

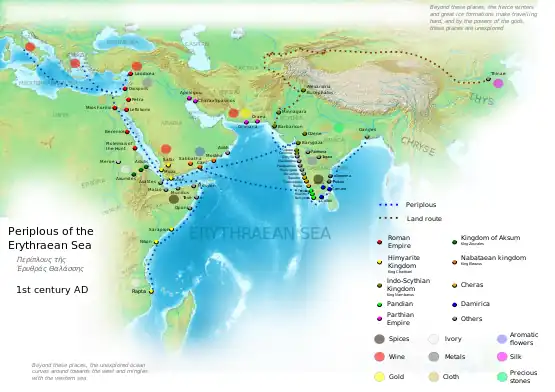

In ancient times, the Kingdom of Punt, which is believed by several Egyptologists to have been situated in the area of modern-day Horn of Africa, had a steady trade link with the Ancient Egyptians and exported precious natural resources such as myrrh, frankincense and gum. This trade network continued all the way into the classical era. The city states of Mossylon, Malao, Mundus, and Avalites in Somalia engaged in a lucrative trade network connecting Somali merchants with Phoenicia, Tabae, Ptolemic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea and the Roman Empire. Somali sailors used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

The periplus described the method of governance as decentralized and consisting of a number of autonomous city-states, these city-states would be governed by their respective local chief or tyrannida.[7] Some cities the berbers living in them were described as very unruly an apparent reference to their independent streak. Whereas others port cities like Malao the natives were described to be peacefull.[8][9]

In ancient times Somalia was known to the Chinese as the "country of Pi-pa-lo", which had four departmental cities each trying to gain the supremacy over the other. It had twenty thousand troops between them, who wore cuirasses, a protective body armor.[10]

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants barred Indian merchants from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula[11] because of the nearby Roman presence. However, they continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from any Roman threat or spies. The reason for barring Indian ships from entering the wealthy Arabian port cities was to protect and hide the exploitative trade practices of the Somali and Arab merchants in the extremely lucrative ancient Red Sea-Mediterranean Sea commerce.[12] The Indian merchants for centuries brought large quantities of cinnamon from Ceylon and the Far East to Somalia and Arabia. This is said to have been the best-kept secret of the Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world. The Romans and Greeks believed the source of cinnamon to have been the Somali peninsula but in reality, the highly valued product was brought to Somalia by way of Indian ships.[13] Through Somali and Arab traders, Indian/Chinese cinnamon was also exported for far higher prices to North Africa, the Near East and Europe, which made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue generator, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across ancient sea and land routes.

Somali sailors were aware of the region's monsoons, and used them to link themselves with the port cities of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. They also developed an understandable way of defining the islands of the Indian Ocean in their navigational reach. They would name archipelagos or groups of islands after the most important island there, from the Somali point of view.[14]

Middle Ages

|

During the Age of the Ajurans, the sultanates and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to Arabia, India, Venetia,[5] Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China.

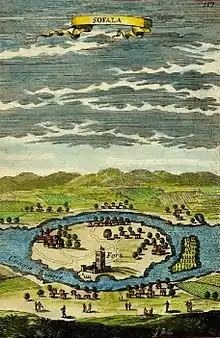

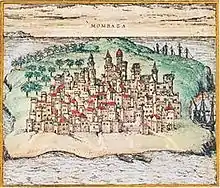

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in India sailed to Mogadishu with fabric and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria[16]), together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[17] Trade with the Hormuz went both ways, and Jewish merchants brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[18] Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century,[19] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities exchanged.[20] Giraffes, zebras, and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between Asia and Africa,[21] and in the process influenced the Chinese language with the Somali language and vice versa. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani meddling, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[22]

During the same period, Somali merchants sailed to Cairo, Damascus, Mocha, Mombasa, Aden, Madagascar, Hyderabad and the islands of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, establishing Somali communities along the way. These travels produced several important individuals such as the Muslim scholars Uthman bin Ali Zayla'i in Egypt, Abd al-Aziz of Mogadishu in the Maldives, as well as the explorer Sa'id of Mogadishu, the latter of whom traveled across the Muslim world and visited China and India in the 14th century.

Early modern era to present

|

"The Somali wanders afar. You will find him working as deck hand, fireman, or steward, on all the great liners trading to the East. I know of a Somali tobacconist in Cardiff, a Somali mechanic in New York, and a Somali trader in Bombay, the latter of whom speaks French, English, and Italian fluently". (Rayne, 1921, 6)[23] |

In the early modern period, successor states of the Adal and Ajuran empires began to flourish in Somalia, continuing the tradition of seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires. The rise of the 19th century Gobroon dynasty in particular saw a rebirth in Somali maritime enterprise. During this period, the Somali agricultural output to Arabian markets was so great that the coast of Somalia came to be known as the Grain Coast of Yemen and Oman.[24] Somali merchants also operated trade factories on the Eritrean coast.[25]

.jpg.webp)

Berbera was the most important port in the Somali Peninsula between the 18th–19th centuries.[6] For centuries, Berbera had extensive trade relations with several historic ports in the Arabian Peninsula. Additionally, the Somali and Ethiopian interiors were very dependent on Berbera for trade, where most of the goods for export arrived from. During the 1833 trading season, the port town swelled to over 70,000 people, and upwards of 6,000 camels laden with goods arrived from the interior within a single day. Berbera was the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as livestock, coffee, frankincense, myrrh, acacia gum, saffron, feathers, wax, ghee, hide (skin), gold and ivory.[26]

According to a trade journal published in 1856, Berbera was described as “the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf (referring to the Gulf of Aden).”:

“The only seaports of importance on this coast are Feyla [Zeila] and Berbera; the former is an Arabian colony, dependent of Mocha, but Berbera is independent of any foreign power. It is, without having the name, the freest port in the world and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf. From the beginning of November to the end of April, a large fair assembles in Berbera, and caravans of 6,000 camels at a time come from the interior loaded with coffee (considered superior to Mocha in Bombay), gum, ivory, hides, skins, grain, cattle, and sour milk, the substitute of fermented drinks in these regions; also much cattle are brought there for the Aden market.”[27]

Historically, the port of Berbera was controlled indigenously between the mercantile Reer Ahmed Nur and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the Habar Awal.[28]

The major Isaaq sub-clans that historically operated from Berbera and other ports and harbors in their domain were known to be adept at trade and seafaring:

Some Isaaq clans are very much given to both seafaring and trade. The setting up of trading posts and the erection of any permanent dwellings used to be strongly resented by the nomads of the deep interior.[29]

During the brief period of imperial hegemony over the Somali Peninsula, Somali sailors and traders frequently joined British and other European ships to the Far East, Europe and the Americas.

Somalia, in the pre-civil war period, possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Muslim world. It consisted of 12 oil tankers (average size 1300 tons), 15 bulk ore carriers (average size 15000 tons), and 207 other crafts with an average tonnage of 5000 to 10000.[30]

Naval warfare

In ancient times, naval engagements between buccaneers and merchant ships were very common in the Gulf of Aden. In the late medieval period, Somali navies regularly engaged their Portuguese counterparts at sea; the Somali coast's commercial reputation naturally attracted the latter. These tensions significantly worsened during the 16th century.

Over the next several decades, Somali-Portuguese tensions would remain high. The increased contact between Somali sailors and Ottoman corsairs worried the Portuguese, prompting the latter to send a punitive expedition against Mogadishu under João de Sepúlveda. The expedition was unsuccessful.[32] Ottoman-Somali cooperation against the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean reached an apogee in the 1580s when Ajuran clients of the Somali coastal cities began to sympathize with the Arabs and Swahilis under Portuguese rule and sent an envoy to the Turkish corsair Mir Ali Bey for a joint expedition against the Portuguese. Bey agreed and was joined by a Somali fleet, which began attacking Portuguese colonies in Southeast Africa.[33] The Somali-Ottoman offensive managed to drive out the Portuguese from several important cities such as Pate, Mombasa and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor sent envoys to India requesting a large Portuguese fleet. This request was answered, and it reversed the previous offensive of the Muslims into one of defense. The Portuguese armada managed to re-take most of the lost cities and punish their leaders. However, they refrained from attacking Mogadishu.[34]

During the post-independence period, the Somali Navy mostly did maritime patrols to prevent ships from illegally infringing on the nation's maritime borders. The Somali Navy and Somali Air Force also regularly collaborated as a deterrent against the Imperial Navy of Ethiopia. In addition, the Somali Navy carried out Search and Rescue (SAR) missions. The National Navy participated in many navy exercises with the United States Navy, the Royal British Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Technology and equipment

- Beden – The prime ancient Somali maritime vessel that today remains the longest surviving sewn ship in East Africa and the world. The ship's construction style is unique to Somalia and significantly differs from extinct sewn ships of Arabia, South India and adjacent islands. An average Beden ship measures 10m or more and is strengthened with a substantial gunwale, attached by trenails. The Somali fishermen also use stone anchors to prevent their ships from being drawn to the shore when fishing.

- Lighthouses – Somalia's historical strategic location within the world's oldest and busiest sea-lanes encouraged the construction of lighthouses to coordinate shipping and to ensure the safe entry of commercial vessels in the nation's many port cities.

- Hourglass – Hourglasses were used on Somali ships for timekeeping.

Port cities

Ancient

- Botiala – In ancient times, the port city of Botiala transported goods such as aromatic woods, gum and incense to Indian, Persian and Arab merchants

- Cape Guardafui – Known in ancient times as the Cape of Spices, it was an important place for the ancient cinnamon and Indian spice trade.

- Damo – Ancient port town in northern Somalia. It likely corresponded with the Periplus "Market of Spices". Holds many historical artifacts and structures, including ancient coins, Roman pottery, drystone buildings, cairns, mosques, walled enclosures, standing stones and platform monuments.[35]

- Essina – Ancient emporium possibly located between the southern ports of Barawa and Merca, based on Ptolemy's work.

- Gondal – Ancient town in southern Somalia. It is considered a predecessor of the port city Kismayo.[36]

- Malao – Ancient port city known for its commerce in frankincense and myrrh in exchange for cloaks, copper and gold from Arsinoe and India.

- Mosylon – The most important ancient port city of the Somali Peninsula, it handled a considerable amount of the Indian Ocean trade through its large ships and extensive harbor.

- Mundus – Ancient port engaged in the fragrant gum and cinnamon trade with the Hellenic world.

- Opone – In ancient times, the port city of Opone traded with merchants from Phoenicia, Egypt, Greece, Persia and the Roman Empire, and connected with traders from as far afield as Indonesia and Malaysia, exchanging spices, silks and other goods.

- Sarapion – Ancient port city in Somalia. It is the possible predecessor of Mogadishu.

- Sesea – Ancient city-state in northern Somalia.

- Tabae – Ancient port where sailors on their way to India could take refuge from the storms of the Indian Ocean.

Medieval

- Barawa – Old port city in Somalia, which in the medieval era came under the influence of Mogadishu and the later Ajuran Empire.

- Berbera – Dominant port city on the Gulf of Aden that had trade relations with the Tang dynasty of China. Berbera maintained its influence well into the early modern period.

- Gondershe – Medieval center of trade that handled smaller vessels sailing from India, Arabia, Persia and the Far East.

- Hobyo – One of the commercial centers of the Ajurans and an important port city for the pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca.

- Kismayo – Sister city of Mogadishu and an important trade outlet during the Gobroon dynasty.

- Merka – Prominent medieval port city that collaborated with the Mogadishans in the Indian Ocean trade.

- Mogadishu – The most important medieval city in East Africa and initiator of the East African gold trade. Before the period of civil strife, Mogadishu continued its historical position as the pre-eminent port city of East Africa.

- Zeila – Adalite city that traded with the Catalans and the Ottomans. Handled most of the trade of the northwestern Horn of Africa.

Early modern and present

- Bulhar – A prosperous port during the 19th century, Bulhar was a trading rival to nearby Berbera

- Eyl – A Dervish city that was utilized for the weapons trade during the Scramble for Africa. Today, Eyl is a growing port city.

- Bosaso – Established by the Somali seafaring company Kaptallah in the early 19th century as Bandar Qassim.

- Las Khorey – Capital of the Warsangali Sultanate, it was at its zenith during the late 18th century. Today, the port continues to export mainly marine products. Somali environmentalist Fatima Jibrell is re-developing the centuries-old port with the aim of creating immediate employment for local residents. Over the long-term, this effort is intended to boost import and export opportunities to Somalia's northern coastal region, and thus also help rebuild communities and livelihoods.

- Qandala – An important port city in the 18th and 19th centuries for the pilgrimage to Mecca, and for the caravan trains that came from the castle city of Botiala.

See also

References

| History of Somalia |

|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |

|

|

- Charles Geshekter, "Somali Maritime History and Regional Sub Cultures: A Neglected Theme of the Somali Crisis

- Phoenicia pg 199

- The Aromatherapy Book by Jeanne Rose and John Hulburd pg 94

- Oman in history By Peter Vine Page 324

- Journal of African History pg.50 by John Donnelly Fage and Roland Anthony Oliver

- Prichard, J. C. (1837). Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind: Ethnography of the African races. Sherwood, Gilbert & Piper. pp. 160.

- Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press, 2001), pp.13–14

- Schoff, Wilfred Harvey (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century. London, Bombay & Calcutta. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Schoff's 1912 translation

- Eastern African History By Robert O. Collins Pg 53

- E. H. Warmington, The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India, (South Asia Books: 1995), p.54

- E. H. Warmington, The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India, (South Asia Books: 1995), p.229

- E. H. Warmington, The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India, (South Asia Books: 1995), p.186

- Historical relations across the Indian Ocean: report and papers of the - Page 23

- pg 4 - The quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, By Terry H. Elkiss

- Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.35

- The return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War pg.22

- The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century By R. J. Barendse

- Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.30

- Chinese Porcelain Marks from Coastal Sites in Kenya: aspects of trade in the Indian Ocean, XIV-XIX centuries. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1978 pg 2

- East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.45

- Nomads, sailors and refugees. A century of Somali migration pg 6

- East Africa and the Indian Ocean By Edward A. Alpers pg 66

- voyage to Abyssinia and travels into the interior of that country by Henry Salt pg 152

- The Colonial Magazine and Commercial-maritime Journal, Volume 2. 1840. p. 22.

- Hunt, Freeman (1856). The Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review, Volume 34. p. 694.

- Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Westview Press. p. 35.

- Journal of African Languages. University of Michigan Press. 1963. p. 27.

- Pakistan Economist 1983 -Page 24 by S. Akhtar

- Tanzania notes and records: the journal of the Tanzania Society pg 76

- The Portuguese period in East Africa - Page 112

- Portuguese rule and Spanish crown in South Africa, 1581-1640 - Page 25

- Four centuries of Swahili verse: a literary history and anthology - Page 11

- Chittick, Neville (1975). An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition. pp. 117–133.

- The Culture of the East African Coast: In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in the Light of Recent Archaeological Discoveries, By Gervase Mathew pg 68

External links

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). pp. 378–384.