Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury OSB (/ˈænsɛlm/; 1033/4–1109), also called Anselm of Aosta (French: Anselme d'Aoste, Italian: Anselmo d'Aosta) after his birthplace and Anselm of Bec (French: Anselme du Bec) after his monastery, was an Italian[4] Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of the Catholic Church, who held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109. After his death, he was canonized as a saint; his feast day is 21 April. He was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by a bull of Pope Clement XI in 1720.

Anselm | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury Doctor of the Church | |

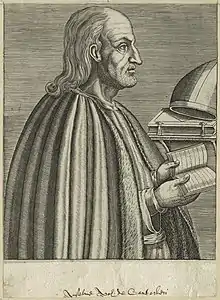

Anselm described on his stamp | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Canterbury |

| See | Canterbury |

| Appointed | 1093 |

| Term ended | 21 April 1109 |

| Predecessor | Lanfranc |

| Successor | Ralph d'Escures |

| Other post(s) | Abbot of Bec |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 4 December 1093 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Anselme d'Aoste c. 1033 |

| Died | 21 April 1109 Canterbury, England |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral |

| Parents | Gundulph Ermenberge |

| Occupation | Monk, prior, abbot, archbishop |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 21 April |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion[1] Lutheranism[2] |

| Title as Saint | Bishop, Confessor, Doctor of the Church (Doctor Magnificus) |

| Canonized | 4 October 1494 Rome, Papal States by Pope Alexander VI |

| Attributes | His mitre, pallium, and crozier His books A ship, representing the spiritual independence of the Church. |

Philosophy career | |

| Notable work | Proslogion Cur Deus Homo |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism Neoplatonism[3] Augustinianism |

Main interests | Metaphysics, theology |

Notable ideas | Argument from Degree Ontological argument Satisfaction theory of atonement |

As Archbishop of Canterbury, he defended the church's interests in England amid the Investiture Controversy. For his resistance to the English kings William II and Henry I, he was exiled twice: once from 1097 to 1100 and then from 1105 to 1107. While in exile, he helped guide the Greek Catholic bishops of southern Italy to adopt Roman rites at the Council of Bari. He worked for the primacy of Canterbury over the archbishop of York and over the bishops of Wales but, though at his death he appeared to have been successful, Pope Paschal II later reversed papal decisions on the matter and restored York's earlier status.

Beginning at Bec, Anselm composed dialogues and treatises with a rational and philosophical approach, which have sometimes caused him to be credited as the founder of Scholasticism. Despite his lack of recognition in this field in his own time, Anselm is now famed as the originator of the ontological argument for the existence of God and of the satisfaction theory of atonement.

Biography

Family

Anselm was born in or around Aosta in Upper Burgundy sometime between April 1033 and April 1034.[6] The area now forms part of the Republic of Italy, but Aosta had been part of the post-Carolingian Kingdom of Burgundy until the death of the childless Rudolph III in 1032.[7] The Emperor Conrad II and Odo II, Count of Blois then went to war over the succession. Humbert the White-Handed, Count of Maurienne, so distinguished himself that he was granted a new county carved out of the secular holdings of the bishop of Aosta. Humbert's son Otto was subsequently permitted to inherit the extensive March of Susa through his wife Adelaide[8] in preference to her uncle's families, who had supported the effort to establish an independent Kingdom of Italy under William V, Duke of Aquitaine. Otto and Adelaide's unified lands[9] then controlled the most important passes in the western Alps and formed the county of Savoy whose dynasty would later rule the kingdoms of Sardinia and Italy.[10][11]

Records during this period are scanty, but both sides of Anselm's immediate family appear to have been dispossessed by these decisions[12] in favour of their extended relations.[13] His father Gundulph[14] or Gundulf[15] or Gondulphe[16] was a Lombard noble,[17] probably one of Adelaide's Arduinici uncles or cousins;[18] his mother Ermenberge[19] was almost certainly the granddaughter of Conrad the Peaceful, related both to the Anselmid bishops of Aosta and to the heirs of Henry II who had been passed over in favour of Conrad.[18] The marriage was thus probably arranged for political reasons but proved ineffective in opposing Conrad after his successful annexation of Burgundy on 1 August 1034.[20] (Bishop Burchard subsequently revolted against imperial control but was defeated and was ultimately translated to the diocese of Lyon.) Ermenberge appears to have been the wealthier partner in the marriage. Gundulph moved to his wife's town,[7] where she held a palace, most likely near the cathedral, along with a villa in the valley.[21] Anselm's father is sometimes described as having a harsh and violent temper[14] but contemporary accounts merely portray him as having been overgenerous or careless with his wealth;[22] Meanwhile, Anselm's mother Ermenberge, patient and devoutly religious,[14] made up for her husband's faults by her own prudent management of the family estates.[22] In later life, there are records of three relations who visited Bec: Folceraldus, Haimo, and Rainaldus. The first repeatedly attempted to exploit Anselm's renown, but was rebuffed since he already had his ties to another monastery, whereas Anselm's attempts to persuade the other two to join the Bec community were unsuccessful.[23]

Early life

At the age of fifteen, Anselm felt the call to enter a monastery but, failing to obtain his father's consent, he was refused by the abbot.[25] The illness he then suffered has been considered by some a psychosomatic effect of his disappointment,[14] but upon his recovery he gave up his studies and for a time lived a carefree life.[14]

Following the death of his mother, probably at the birth of his sister Richera,[26] Anselm's father repented his own earlier lifestyle but professed his new faith with a severity that the boy found likewise unbearable.[27] When Gundulph entered a monastery,[28] Anselm, at age 23,[29] left home with a single attendant,[14] crossed the Alps, and wandered through Burgundy and France for three years.[25][lower-alpha 1] His countryman Lanfranc of Pavia was then prior of the Benedictine abbey of Bec in Normandy. Attracted by Lanfranc's reputation, Anselm reached Normandy in 1059.[14] After spending some time in Avranches, he returned the next year. His father having died, he consulted with Lanfranc as to whether to return to his estates and employ their income in providing alms for the poor or to renounce them, becoming a hermit or a monk at Bec or Cluny.[30] Given what he saw as his own conflict of interest, Lanfranc sent Anselm to Maurilius, the archbishop of Rouen, who convinced him to enter Bec as a novice at the age of 27.[25] Probably in his first year, he wrote his first work on philosophy, a treatment of Latin paradoxes called the Grammarian.[31] Over the next decade, the Rule of Saint Benedict reshaped his thought.[32]

Early years

Three years later, in 1063, Duke William II summoned Lanfranc to serve as the abbot of his new abbey of St Stephen at Caen[14] and the monks of Bec, despite the initial hesitation of some on account of his youth,[25] elected Anselm prior.[33] A notable opponent was a young monk named Osborne. Anselm overcame his hostility first by praising, indulging, and privileging him in all things despite his hostility and then, when his affection and trust were gained, gradually withdrawing all preference until he upheld the strictest obedience.[34] Along similar lines, he remonstrated with a neighboring abbot who complained that his charges were incorrigible despite being beaten "night and day".[35] After fifteen years, in 1078, Anselm was unanimously elected as Bec's abbot following the death of its founder,[36] the warrior-monk Herluin.[14] He was blessed as abbot by Gilbert d'Arques, Bishop of Évreux, on 22 February 1079.[37]

Under Anselm's direction, Bec became the foremost seat of learning in Europe,[14] attracting students from France, Italy, and elsewhere.[38] During this time, he wrote the Monologion and Proslogion.[14] He then composed a series of dialogues on the nature of truth, free will,[14] and the fall of Satan.[31] When the nominalist Roscelin attempted to appeal to the authority of Lanfranc and Anselm at his trial for the heresy of tritheism at Soissons in 1092,[39] Anselm composed the first draft of De Fide Trinitatis as a rebuttal and as a defence of Trinitarianism and universals.[40] The fame of the monastery grew not only from his intellectual achievements, however, but also from his good example[30] and his loving, kindly method of discipline,[14] particularly with the younger monks.[25] There was also admiration for his spirited defence of the abbey's independence from lay and archiepiscopal control, especially in the face of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester and the new Archbishop of Rouen, William Bona Anima.[41]

In England

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, devoted lords had given the abbey extensive lands across the Channel.[14] Anselm occasionally visited to oversee the monastery's property, to wait upon his sovereign William I of England (formerly Duke William II of Normandy),[42] and to visit Lanfranc, who had been installed as archbishop of Canterbury in 1070.[43] He was respected by William I[44] and the good impression he made while in Canterbury made him the favourite of its cathedral chapter as a future successor to Lanfranc.[14] Instead, upon the archbishop's death in 1089, King William II—William Rufus or William the Red—refused the appointment of any successor and appropriated the see's lands and revenues for himself.[14] Fearing the difficulties that would attend being named to the position in opposition to the king, Anselm avoided journeying to England during this time.[14] The gravely ill Hugh, Earl of Chester, finally lured him over with three pressing messages in 1092,[45] seeking advice on how best to handle the establishment of a new monastery at St Werburgh's.[25] Hugh was recovered by the time of Anselm's arrival,[25] but he was occupied four[14] or five months by his assistance.[25] He then travelled to his former pupil Gilbert Crispin, abbot of Westminster, and waited, apparently delayed by the need to assemble the donors of Bec's new lands in order to obtain royal approval of the grants.[46]

At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived[47] but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his sinful behavior was responsible,[48] he summoned Anselm to hear his confession and administer last rites.[46] He published a proclamation releasing his captives, discharging his debts, and promising to henceforth govern according to the law.[25] On 6 March 1093, he further nominated Anselm to fill the vacancy at Canterbury; the clerics gathered at court acclaiming him, forcing the crozier into his hands, and bodily carrying him to a nearby church amid a Te Deum.[49] Anselm tried to refuse on the grounds of age and ill-health for months[43] and the monks of Bec refused to give him permission to leave them.[50] Negotiations were handled by the recently restored Bishop William of Durham and Robert, count of Meulan.[51] On 24 August, Anselm gave King William the conditions under which he would accept the position, which amounted to the agenda of the Gregorian Reform: the king would have to return the Catholic Church lands which had been seized, accept his spiritual counsel, and forswear Antipope Clement III in favour of Urban II.[52] William Rufus was exceedingly reluctant to accept these conditions: he consented only to the first[53] and, a few days afterwards, reneged on that, suspending preparations for Anselm's investiture. Public pressure forced William to return to Anselm and in the end they settled on a partial return of Canterbury's lands as his own concession.[54] Anselm received dispensation from his duties in Normandy,[14] did homage to William, and—on 25 September 1093—was enthroned at Canterbury Cathedral.[55] The same day, William II finally returned the lands of the see.[53]

From the mid-8th century, it had become the custom that metropolitan bishops could not be consecrated without a woolen pallium given or sent by the pope himself.[56] Anselm insisted that he journey to Rome for this purpose but William would not permit it. Amid the Investiture Controversy, Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV had deposed each other twice; bishops loyal to Henry finally elected Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as a second pope. In France, Philip I had recognized Gregory and his successors Victor III and Urban II, but Guibert (as "Clement III") held Rome after 1084.[57] William had not chosen a side and maintained his right to prevent the acknowledgement of either pope by an English subject prior to his choice.[58] In the end, a ceremony was held to consecrate Anselm as archbishop on 4 December, without the pallium.[53]

Archbishop of Canterbury

As archbishop, Anselm maintained his monastic ideals, including stewardship, prudence, and proper instruction, prayer and contemplation.[59] Anselm advocated for reform and interests of Canterbury.[60] As such, he repeatedly pressed the English monarchy for support of the reform agenda.[61] His principled opposition to royal prerogatives over the Catholic Church, meanwhile, twice led to his exile from England.[62]

The traditional view of historians has been to see Anselm as aligned with the papacy against lay authority and Anselm's term in office as the English theatre of the Investiture Controversy begun by Pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV.[62] By the end of his life, he had proven successful, having freed Canterbury from submission to the English king,[63] received papal recognition of the submission of wayward York[64] and the Welsh bishops, and gained strong authority over the Irish bishops.[65] He died before the Canterbury–York dispute was definitively settled, however, and Pope Honorius II finally found in favour of York instead.[66]

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of Canterbury Cathedral from Lanfranc's initial plans.[68] The eastern end was demolished and an expanded choir placed over a large and well-decorated crypt, doubling the cathedral's length.[69] The new choir formed a church unto itself with its own transepts and a semicircular ambulatory opening into three chapels.[70]

Conflicts with William Rufus

Anselm's vision was of a Catholic Church with its own internal authority, which clashed with William II's desire for royal control over both church and State.[61] One of Anselm's first conflicts with William came in the month he was consecrated. William II was preparing to wrest Normandy from his elder brother, Robert II, and needed funds.[71] Anselm was among those expected to pay him. He offered £500 but William refused, encouraged by his courtiers to insist on 1000 as a kind of annates for Anselm's elevation to archbishop. Anselm not only refused, he further pressed the king to fill England's other vacant positions, permit bishops to meet freely in councils, and to allow Anselm to resume enforcement of canon law, particularly against incestuous marriages,[25] until he was ordered to silence.[72] When a group of bishops subsequently suggested that William might now settle for the original sum, Anselm replied that he had already given the money to the poor and "that he disdained to purchase his master's favour as he would a horse or ass".[39] The king being told this, he replied Anselm's blessing for his invasion would not be needed as "I hated him before, I hate him now, and shall hate him still more hereafter".[72] Withdrawing to Canterbury, Anselm began work on the Cur Deus Homo.[39]

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office.[39] On 25 February 1095, the Lords Spiritual and Temporal of England met in a council at Rockingham to discuss the issue. The next day, William ordered the bishops not to treat Anselm as their primate or as Canterbury's archbishop, as he openly adhered to Urban. The bishops sided with the king, the Bishop of Durham presenting his case[74] and even advising William to depose and exile Anselm.[75] The nobles siding with Anselm, the conference ended in deadlock and the matter was postponed. Immediately following this, William secretly sent William Warelwast and Gerard to Italy,[60] prevailing on Urban to send a legate bearing Canterbury's pallium.[76] Walter, bishop of Albano, was chosen and negotiated in secret with William's representative, the Bishop of Durham.[77] The king agreed to publicly support Urban's cause in exchange for acknowledgement of his rights to accept no legates without invitation and to block clerics from receiving or obeying papal letters without his approval. William's greatest desire was for Anselm to be removed from office. Walter said that "there was good reason to expect a successful issue in accordance with the king's wishes" but, upon William's open acknowledgement of Urban as pope, Walter refused to depose the archbishop.[78] William then tried to sell the pallium to others, failed,[79] tried to extract a payment from Anselm for the pallium, but was again refused. William then tried to personally bestow the pallium to Anselm, an act connoting the church's subservience to the throne, and was again refused.[80] In the end, the pallium was laid on the altar at Canterbury, whence Anselm took it on 10 June 1095.[80]

The First Crusade was declared at the Council of Clermont in November.[lower-alpha 2] Despite his service for the king which earned him rough treatment from Anselm's biographer Eadmer,[82][83] upon the grave illness of the Bishop of Durham in December, Anselm journeyed to console and bless him on his deathbed.[84] Over the next two years, William opposed several of Anselm's efforts at reform—including his right to convene a council[44]—but no overt dispute is known. However, in 1094, the Welsh had begun to recover their lands from the Marcher Lords and William's 1095 invasion had accomplished little; two larger forays were made in 1097 against Cadwgan in Powys and Gruffudd in Gwynedd. These were also unsuccessful and William was compelled to erect a series of border fortresses.[85] He charged Anselm with having given him insufficient knights for the campaign and tried to fine him.[86] In the face of William's refusal to fulfill his promise of church reform, Anselm resolved to proceed to Rome—where an army of French crusaders had finally installed Urban—in order to seek the counsel of the pope.[61] William again denied him permission. The negotiations ended with Anselm being "given the choice of exile or total submission": if he left, William declared he would seize Canterbury and never again receive Anselm as archbishop; if he were to stay, William would impose his fine and force him to swear never again to appeal to the papacy.[87]

First exile

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097.[61] Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death.[88] From Lyon, Anselm wrote to Urban, requesting that he be permitted to resign his office. Urban refused but commissioned him to prepare a defence of the Western doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit against representatives from the Greek Church.[89] Anselm arrived in Rome by April[89] and, according to his biographer Eadmer, lived beside the pope during the Siege of Capua in May.[90] Count Roger's Saracen troops supposedly offered him food and other gifts but the count actively resisted the clerics' attempts to convert them to Catholicism.[90]

At the Council of Bari in October, Anselm delivered his defence of the Filioque and the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist before 185 bishops.[91] Although this is sometimes portrayed as a failed ecumenical dialogue, it is more likely that the "Greeks" present were the local bishops of Southern Italy,[92] some of whom had been ruled by Constantinople as recently as 1071.[91] The formal acts of the council have been lost and Eadmer's account of Anselm's speech principally consists of descriptions of the bishops' vestments, but Anselm later collected his arguments on the topic as De Processione Spiritus Sancti.[92] Under pressure from their Norman lords, the Italian Greeks seem to have accepted papal supremacy and Anselm's theology.[92] The council also condemned William II. Eadmer credited Anselm with restraining the pope from excommunicating him,[89] although others attribute Urban's politic nature.[93]

Anselm was present in a seat of honour at the Easter Council at St Peter's in Rome the next year.[94] There, amid an outcry to address Anselm's situation, Urban renewed bans on lay investiture and on clerics doing homage.[95] Anselm departed the next day, first for Schiavi—where he completed his work Cur Deus Homo—and then for Lyon.[93][96]

Conflicts with Henry I

William Rufus was killed hunting in the New Forest on 2 August 1100. His brother Henry was present and moved quickly to secure the throne before the return of his elder brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, from the First Crusade. Henry invited Anselm to return, pledging in his letter to submit himself to the archbishop's counsel.[97] The cleric's support of Robert would have caused great trouble but Anselm returned before establishing any other terms than those offered by Henry.[98] Once in England, Anselm was ordered by Henry to do homage for his Canterbury estates[99] and to receive his investiture by ring and crozier anew.[100] Despite having done so under William, the bishop now refused to violate canon law. Henry for his part refused to relinquish a right possessed by his predecessors and even sent an embassy to Pope Paschal II to present his case.[93] Paschal reaffirmed Urban's bans to that mission and the one that followed it.[93]

Meanwhile, Anselm publicly supported Henry against the claims and threatened invasion of his brother Robert Curthose. Anselm wooed wavering barons to the king's cause, emphasizing the religious nature of their oaths and duty of loyalty;[101] he supported the deposition of Ranulf Flambard, the disloyal new bishop of Durham;[102] and he threatened Robert with excommunication.[103] The lack of popular support greeting his invasion near Portsmouth compelled Robert to accept the Treaty of Alton instead, renouncing his claims for an annual payment of 3000 marks.

Anselm held a council at Lambeth Palace which found that Henry's beloved Matilda had not technically become a nun and was thus eligible to wed and become queen.[104] On Michaelmas in 1102, Anselm was finally able to convene a general church council at London, establishing the Gregorian Reform within England. The council prohibited marriage, concubinage, and drunkenness to all those in holy orders,[105] condemned sodomy[106] and simony,[103] and regulated clerical dress.[103] Anselm also obtained a resolution against the British slave trade.[107] Henry supported Anselm's reforms and his authority over the English Church, but continued to assert his own authority over Anselm. Upon their return, the three bishops he had dispatched on his second delegation to the pope claimed—in defiance of Paschal's sealed letter to Anselm, his public acts, and the testimony of the two monks who had accompanied them—that the pontiff had been receptive to Henry's counsel and secretly approved of Anselm's submission to the crown.[108] In 1103, then, Anselm consented to journey himself to Rome, along with the king's envoy William Warelwast.[109] Anselm supposedly travelled in order to argue the king's case for a dispensation[110] but, in response to this third mission, Paschal fully excommunicated the bishops who had accepted investment from Henry, though sparing the king himself.[93]

Second exile

After this ruling, Anselm received a letter forbidding his return and withdrew to Lyon to await Paschal's response.[93] On 26 March 1105, Paschal again excommunicated prelates who had accepted investment from Henry and the advisors responsible, this time including Robert de Beaumont, Henry's chief advisor.[111] He further finally threatened Henry with the same;[112] in April, Anselm sent messages to the king directly[113] and through his sister Adela expressing his own willingness to excommunicate Henry.[93] This was probably a negotiation tactic[114] but it came at a critical period in Henry's reign[93] and it worked: a meeting was arranged and a compromise concluded at L'Aigle on 22 July 1105. Henry would forsake lay investiture if Anselm obtained Paschal's permission for clerics to do homage for their lands;[115][116] Henry's bishops'[93] and counselors' excommunications were to be lifted provided they advise him to obey the papacy (Anselm performed this act on his own authority and later had to answer for it to Paschal);[115] the revenues of Canterbury would be returned to the archbishop; and priests would no longer be permitted to marry.[116] Anselm insisted on the agreement's ratification by the pope before he would consent to return to England, but wrote to Paschal in favour of the deal, arguing that Henry's forsaking of lay investiture was a greater victory than the matter of homage.[117] On 23 March 1106, Paschal wrote Anselm accepting the terms established at L'Aigle, although both clerics saw this as a temporary compromise and intended to continue pressing for reforms,[118] including the ending of homage to lay authorities.[119]

Even after this, Anselm refused to return to England.[120] Henry travelled to Bec and met with him on 15 August 1106. Henry was forced to make further concessions. He restored to Canterbury all the churches that had been seized by William or during Anselm's exile, promising that nothing more would be taken from them and even providing Anselm with a security payment. Henry had initially taxed married clergy and, when their situation had been outlawed, had made up the lost revenue by controversially extending the tax over all Churchmen.[121] He now agreed that any prelate who had paid this would be exempt from taxation for three years. These compromises on Henry's part strengthened the rights of the church against the king. Anselm returned to England before the new year.[93]

Final years

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop,[63] Henry formally renouncing the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church.[93] The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric.[93] He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the archbishop of York to Canterbury, so that future archbishops-elect would have to profess obedience before receiving it.[64] The incumbent archbishop Thomas II had received his own pallium directly and insisted on York's independence. From his deathbed, Anselm anathematized all who failed to recognize Canterbury's primacy over all the English Church. This ultimately forced Henry to order Thomas to confess his obedience to Anselm's successor.[65] On his deathbed, he announced himself content, except that he had a treatise in mind on the origin of the soul and did not know, once he was gone, if another was likely to compose it.[124]

He died on Holy Wednesday, 21 April 1109.[110] His remains were translated to Canterbury Cathedral[125] and laid at the head of Lanfranc at his initial resting place to the south of the Altar of the Holy Trinity (now St Thomas's Chapel).[128] During the church's reconstruction after the disastrous fire of the 1170s, his remains were relocated,[128] although it is now uncertain where.

On 23 December 1752, Archbishop Herring was contacted by Count Perron, the Sardinian ambassador, on behalf of King Charles Emmanuel, who requested permission to translate Anselm's relics to Italy.[129] (Charles had been duke of Aosta during his minority.) Herring ordered his dean to look into the matter, saying that while "the parting with the rotten Remains of a Rebel to his King, a Slave to the Popedom, and an Enemy to the married Clergy (all this Anselm was)" would be no great matter, he likewise "should make no Conscience of palming on the Simpletons any other old Bishop with the Name of Anselm".[131] The ambassador insisted on witnessing the excavation, however,[133] and resistance on the part of the prebendaries seems to have quieted the matter.[126] They considered the state of the cathedral's crypts would have offended the sensibilities of a Catholic and that it was probable that Anselm had been removed to near the altar of SS Peter and Paul, whose side chapel to the right (i.e., south) of the high altar took Anselm's name following his canonization. At that time, his relics would presumably have been placed in a shrine and its contents "disposed of" during the Reformation.[128] The ambassador's own investigation was of the opinion that Anselm's body had been confused with Archbishop Theobald's and likely remained entombed near the altar of the Virgin Mary,[135] but in the uncertainty nothing further seems to have been done then or when inquiries were renewed in 1841.[137]

Writings

Anselm has been called "the most luminous and penetrating intellect between St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas"[110] and "the father of scholasticism",[40] Scotus Erigena having employed more mysticism in his arguments.[93] Anselm's works are considered philosophical as well as theological since they endeavor to render Christian tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational system.[138] Anselm also studiously analyzed the language used in his subjects, carefully distinguishing the meaning of the terms employed from the verbal forms, which he found at times wholly inadequate.[139] His worldview was broadly Neoplatonic, as it was reconciled with Christianity in the works of St Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius,[3][lower-alpha 3] with his understanding of Aristotelian logic gathered from the works of Boethius.[141][142][40] He or the thinkers in northern France who shortly followed him—including Abelard, William of Conches, and Gilbert of Poitiers—inaugurated "one of the most brilliant periods of Western philosophy", innovating logic, semantics, ethics, metaphysics, and other areas of philosophical theology.[143]

Anselm held that faith necessarily precedes reason, but that reason can expand upon faith:[144] "And I do not seek to understand that I may believe but believe that I might understand. For this too I believe since, unless I first believe, I shall not understand".[lower-alpha 4][145] This is possibly drawn from Tractate XXIX of St Augustine's Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John: regarding John 7:14–18, Augustine counseled "Do not seek to understand in order to believe but believe that thou may understand".[146] Anselm rephrased the idea repeatedly[lower-alpha 5] and Thomas Williams(SEP 2007) considered that his aptest motto was the original title of the Proslogion, "faith seeking understanding", which intended "an active love of God seeking a deeper knowledge of God".[147] Once the faith is held fast, however, he argued an attempt must be made to demonstrate its truth by means of reason: "To me, it seems to be negligence if, after confirmation in the faith, we do not study to understand that which we believe".[lower-alpha 6][145] Merely rational proofs are always, however, to be tested by scripture[148][149] and he employs Biblical passages and "what we believe" (quod credimus) at times to raise problems or to present erroneous understandings, whose inconsistencies are then resolved by reason.[150]

Stylistically, Anselm's treatises take two basic forms, dialogues and sustained meditations.[150] In both, he strove to state the rational grounds for central aspects of Christian doctrines as a pedagogical exercise for his initial audience of fellow monks and correspondents.[150] The subjects of Anselm's works were sometimes dictated by contemporary events, such as his speech at the Council of Bari or the need to refute his association with the thinking of Roscelin, but he intended for his books to form a unity, with his letters and latter works advising the reader to consult his other books for the arguments supporting various points in his reasoning.[151] It seems to have been a recurring problem that early drafts of his works were copied and circulated without his permission.[150]

While at Bec, Anselm composed:[31]

- De Grammatico

- Monologion

- Proslogion

- De Veritate

- De Libertate Arbitrii

- De Casu Diaboli

- De Fide Trinitatis, also known as De Incarnatione Verbi[40]

While archbishop of Canterbury, he composed:[31]

- Cur Deus Homo

- De Conceptu Virginali

- De Processione Spiritus Sancti

- De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati

- De Sacramentis Ecclesiae

- De Concordia

Monologion

The Monologion (Latin: Monologium, "Monologue"), originally entitled A Monologue on the Reason for Faith (Monoloquium de Ratione Fidei)[152][lower-alpha 7] and sometimes also known as An Example of Meditation on the Reason for Faith (Exemplum Meditandi de Ratione Fidei),[154][lower-alpha 8] was written in 1075 and 1076.[31] It follows St Augustine to such an extent that Gibson argues neither Boethius nor Anselm state anything which was not already dealt with in greater detail by Augustine's De Trinitate;[156] Anselm even acknowledges his debt to that work in the Monologion's prologue.[157] However, he takes pains to present his reasons for belief in God without appeal to scriptural or patristic authority,[158] using new and bold arguments.[159] He attributes this style—and the book's existence—to the requests of his fellow monks that "nothing whatsoever in these matters should be made convincing by the authority of Scripture, but whatsoever... the necessity of reason would concisely prove".[160]

In the first chapter, Anselm begins with a statement that anyone should be able to convince themselves of the existence of God through reason alone "if he is even moderately intelligent".[161] He argues that many different things are known as "good", in many varying kinds and degrees. These must be understood as being judged relative to a single attribute of goodness.[162] He then argues that goodness is itself very good and, further, is good through itself. As such, it must be the highest good and, further, "that which is supremely good is also supremely great. There is, therefore, some one thing that is supremely good and supremely great—in other words, supreme among all existing things."[163] Chapter 2 follows a similar argument, while Chapter 3 argues that the "best and greatest and supreme among all existing things" must be responsible for the existence of all other things.[163] Chapter 4 argues that there must be a highest level of dignity among existing things and that highest level must have a single member. "Therefore, there is a certain nature or substance or essence who through himself is good and great and through himself is what he is; through whom exists whatever truly is good or great or anything at all; and who is the supreme good, the supreme great thing, the supreme being or subsistent, that is, supreme among all existing things."[163] The remaining chapters of the book are devoted to consideration of the attributes necessary to such a being.[163] The Euthyphro dilemma, although not addressed by that name, is dealt with as a false dichotomy.[164] God is taken to neither conform to nor invent the moral order but to embody it:[164] in each case of his attributes, "God having that attribute is precisely that attribute itself".[165]

A letter survives of Anselm responding to Lanfranc's criticism of the work. The elder cleric took exception to its lack of appeals to scripture and authority.[157] The preface of the Proslogion records his own dissatisfaction with the Monologion's arguments, since they are rooted in a posteriori evidence and inductive reasoning.[159]

Proslogion

The Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, "Discourse"), originally entitled Faith Seeking Understanding (Fides Quaerens Intellectum) and then An Address on God's Existence (Alloquium de Dei Existentia),[152][166][lower-alpha 9] was written over the next two years (1077–1078).[31] It is written in the form of an extended direct address to God.[150] It grew out of his dissatisfaction with the Monologion's interlinking and contingent arguments.[150] His "single argument that needed nothing but itself alone for proof, that would by itself be enough to show that God really exists"[167] is commonly[lower-alpha 10] taken to be merely the second chapter of the work. In it, Anselm reasoned that even atheists can imagine a greatest being, having such attributes that nothing greater could exist (id quo nihil maius cogitari possit).[110] However, if such a being's attributes did not include existence, a still greater being could be imagined: one with all of the attributes of the first and existence. Therefore, the truly greatest possible being must necessarily exist. Further, this necessarily-existing greatest being must be God, who therefore necessarily exists.[159] This reasoning was known to the Scholastics as "Anselm's argument" (ratio Anselmi) but it became known as the ontological argument for the existence of God following Kant's treatment of it.[167][lower-alpha 11]

More probably, Anselm intended his "single argument" to include most of the rest of the work as well,[150] wherein he establishes the attributes of God and their compatibility with one another. Continuing to construct a being greater than which nothing else can be conceived, Anselm proposes such a being must be "just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be".[170] Chapter 6 specifically enumerates the additional qualities of awareness, omnipotence, mercifulness, impassibility (inability to suffer),[169] and immateriality;[171] Chapter 11, self-existent,[171] wisdom, goodness, happiness, and permanence; and Chapter 18, unity.[169] Anselm addresses the question-begging nature of "greatness" in this formula partially by appeal to intuition and partially by independent consideration of the attributes being examined.[171] The incompatibility of, e.g., omnipotence, justness, and mercifulness are addressed in the abstract by reason, although Anselm concedes that specific acts of God are a matter of revelation beyond the scope of reasoning.[172] At one point during the 15th chapter, he reaches the conclusion that God is "not only that than which nothing greater can be thought but something greater than can be thought".[150] In any case, God's unity is such that all of his attributes are to be understood as facets of a single nature: "all of them are one and each of them is entirely what [God is] and what the other[s] are".[173] This is then used to argue for the triune nature of the God, Jesus, and "the one love common to [God] and [his] Son, that is, the Holy Spirit who proceeds from both".[174] The last three chapters are a digression on what God's goodness might entail.[150] Extracts from the work were later compiled under the name Meditations or The Manual of St Austin.[25]

Responsio

The argument presented in the Proslogion has rarely seemed satisfactory[159][lower-alpha 12] and was swiftly opposed by Gaunilo, a monk from the abbey of Marmoutier in Tours.[178] His book "for the fool" (Liber pro Insipiente)[lower-alpha 13] argues that we cannot arbitrarily pass from idea to reality[159] (de posse ad esse not fit illatio).[40] The most famous of Gaunilo's objections is a parody of Anselm's argument involving an island greater than which nothing can be conceived.[167] Since we can conceive of such an island, it exists in our understanding and so must exist in reality. This is, however, absurd, since its shore might arbitrarily be increased and in any case varies with the tide.

Anselm's reply (Responsio) or apology (Liber Apologeticus)[159] does not address this argument directly, which has led Klima,[181] Grzesik,[40] and others to construct replies for him and led Wolterstorff[182] and others to conclude that Gaunilo's attack is definitive.[167] Anselm, however, considered that Gaunilo had misunderstood his argument.[167][178] In each of Gaunilo's four arguments, he takes Anselm's description of "that than which nothing greater can be thought" to be equivalent to "that which is greater than everything else that can be thought".[178] Anselm countered that anything which does not actually exist is necessarily excluded from his reasoning and anything which might or probably does not exist is likewise aside the point. The Proslogion had already stated "anything else whatsoever other than [God] can be thought not to exist".[183] The Proslogion's argument concerns and can only concern the single greatest entity out of all existing things. That entity both must exist and must be God.[167]

Dialogues

All of Anselm's dialogues take the form of a lesson between a gifted and inquisitive student and a knowledgeable teacher. Except for in Cur Deus Homo, the student is not identified but the teacher is always recognizably Anselm himself.[150]

Anselm's De Grammatico ("On the Grammarian"), of uncertain date,[lower-alpha 14] deals with eliminating various paradoxes arising from the grammar of Latin nouns and adjectives[154] by examining the syllogisms involved to ensure the terms in the premises agree in meaning and not merely expression.[185] The treatment shows a clear debt to Boethius's treatment of Aristotle.[141]

Between 1080 and 1086, while still at Bec, Anselm composed the dialogues De Veritate ("On Truth"), De Libertate Arbitrii ("On the Freedom of Choice"), and De Casu Diaboli ("On the Devil's Fall").[31] De Veritate is concerned not merely with the truth of statements but with correctness in will, action, and essence as well.[186] Correctness in such matters is understood as doing what a thing ought or was designed to do.[186] Anselm employs Aristotelian logic to affirm the existence of an absolute truth of which all other truth forms separate kinds. He identifies this absolute truth with God, who therefore forms the fundamental principle both in the existence of things and the correctness of thought.[159] As a corollary, he affirms that "everything that is, is rightly".[188] De Libertate Arbitrii elaborates Anselm's reasoning on correctness with regard to free will. He does not consider this a capacity to sin but a capacity to do good for its own sake (as opposed to owing to coercion or for self-interest).[186] God and the good angels therefore have free will despite being incapable of sinning; similarly, the non-coercive aspect of free will enabled man and the rebel angels to sin, despite this not being a necessary element of free will itself.[189] In De Casu Diaboli, Anselm further considers the case of the fallen angels, which serves to discuss the case of rational agents in general.[190] The teacher argues that there are two forms of good—justice (justicia) and benefit (commodum)—and two forms of evil: injustice and harm (incommodum). All rational beings seek benefit and shun harm on their own account but independent choice permits them to abandon bounds imposed by justice.[190] Some angels chose their own happiness in preference to justice and were punished by God for their injustice with less happiness. The angels who upheld justice were rewarded with such happiness that they are now incapable of sin, there being no happiness left for them to seek in opposition to the bounds of justice.[189] Humans, meanwhile, retain the theoretical capacity to will justly but, owing to the Fall, they are incapable of doing so in practice except by divine grace.[191]

Cur Deus Homo

Cur Deus Homo ("Why God was a Man") was written from 1095 to 1098 once Anselm was already archbishop of Canterbury[31] as a response for requests to discuss the Incarnation.[192] It takes the form of a dialogue between Anselm and Boso, one of his students.[193] Its core is a purely rational argument for the necessity of the Christian mystery of atonement, the belief that Jesus's crucifixion was necessary to atone for mankind's sin. Anselm argues that, owing to the Fall and mankind's fallen nature ever since, humanity has offended God. Divine justice demands restitution for sin but human beings are incapable of providing it, as all the actions of men are already obligated to the furtherance of God's glory.[194] Further, God's infinite justice demands infinite restitution for the impairment of his infinite dignity.[191] The enormity of the offence led Anselm to reject personal acts of atonement, even Peter Damian's flagellation, as inadequate[195] and ultimately vain.[196] Instead, full recompense could only be made by God, which His infinite mercy inclines Him to provide. Atonement for humanity, however, could only be made through the figure of Jesus, as a sinless being both fully divine and fully human.[192] Taking it upon himself to offer his own life on our behalf, his crucifixion accrues infinite worth, more than redeeming mankind and permitting it to enjoy a just will in accord with its intended nature.[191] This interpretation is notable for permitting divine justice and mercy to be entirely compatible[162] and has exercised immense influence over church doctrine,[159][197] largely supplanting the earlier theory developed by Origen and Gregory of Nyssa[110] that had focused primarily on Satan's power over fallen man.[159] Cur Deus Homo is often accounted Anselm's greatest work,[110] but the legalist and amoral nature of the argument, along with its neglect of the individuals actually being redeemed, has been criticized both by comparison with the treatment by Abelard[159] and for its subsequent development in Protestant theology.[198]

.jpg.webp)

Other works

Anselm's De Fide Trinitatis et de Incarnatione Verbi Contra Blasphemias Ruzelini ("On Faith in the Trinity and on the Incarnation of the Word Against the Blasphemies of Roscelin"),[40] also known as Epistolae de Incarnatione Verbi ("Letters on the Incarnation of the Word"),[31] was written in two drafts in 1092 and 1094.[40] It defended Lanfranc and Anselm from association with the supposedly tritheist heresy espoused by Roscelin of Compiègne, as well as arguing in favour of Trinitarianism and universals.

De Conceptu Virginali et de Originali Peccato ("On the Virgin Conception and Original Sin") was written in 1099.[31] He claimed to have written it out of a desire to expand on an aspect of Cur Deus Homo for his student and friend Boso and takes the form of Anselm's half of a conversation with him.[150] Although Anselm denied belief in Mary's Immaculate Conception,[199] his thinking laid two principles which formed the groundwork for that dogma's development. The first is that it was proper that Mary should be so pure that—apart from God—no purer being could be imagined. The second was his treatment of original sin. Earlier theologians had held that it was transmitted from generation to generation by the sinful nature of sex. As in his earlier works, Anselm instead held that Adam's sin was borne by his descendants through the change in human nature which occurred during the Fall. Parents were unable to establish a just nature in their children which they had never had themselves.[200] This would subsequently be addressed in Mary's case by dogma surrounding the circumstances of her own birth.

De Processione Spiritus Sancti Contra Graecos ("On the Procession of the Holy Spirit Against the Greeks"),[166] written in 1102,[31] is a recapitulation of Anselm's treatment of the subject at the Council of Bari.[92] He discussed the Trinity first by stating that human beings could not know God from Himself but only from analogy. The analogy that he used was the self-consciousness of man. The peculiar double-nature of consciousness, memory, and intelligence represent the relation of the Father to the Son. The mutual love of these two (memory and intelligence), proceeding from the relation they hold to one another, symbolizes the Holy Spirit.[159]

De Concordia Praescientiae et Praedestinationis et Gratiae Dei cum Libero Arbitrio ("On the Harmony of Foreknowledge and Predestination and the Grace of God with Free Choice") was written from 1107 to 1108.[31] Like the De Conceptu Virginali, it takes the form of a single narrator in a dialogue, offering presumable objections from the other side.[150] Its treatment of free will relies on Anselm's earlier works, but goes into greater detail as to the ways in which there is no actual incompatibility or paradox created by the divine attributes.[151] In its 5th chapter, Anselm reprises his consideration of eternity from the Monologion. "Although nothing is there except what is present, it is not the temporal present, like ours, but rather the eternal, within which all times altogether are contained. If in a certain way the present time contains every place and all the things that are in any place, likewise, every time is encompassed in the eternal present, and everything that is in any time."[202] It is an overarching present, all beheld at once by God, thus permitting both his "foreknowledge" and genuine free choice on the part of mankind.[203]

Fragments survive of the work Anselm left unfinished at his death, which would have been a dialogue concerning certain pairs of opposites, including ability/inability, possibility/impossibility, and necessity/freedom.[204] It is thus sometimes cited under the name De Potestate et Impotentia, Possibilitate et Impossibilitate, Necessitate et Libertate.[40] Another work, probably left unfinished by Anselm and subsequently revised and expanded, was De Humanis Moribus per Similitudines ("On Mankind's Morals, Told Through Likenesses") or De Similitudinibus ("On Likenesses").[205] A collection of his sayings (Dicta Anselmi) was compiled, probably by the monk Alexander.[206] He also composed prayers to various saints.[17]

Anselm wrote nearly 500 surviving letters (Epistolae) to clerics, monks, relatives, and others,[207] the earliest being those written to the Norman monks who followed Lanfranc to England in 1070.[17] Southern asserts that all of Anselm's letters "even the most intimate" are statements of his religious beliefs, consciously composed so as to be read by many others.[208] His long letters to Waltram, bishop of Naumberg in Germany (Epistolae ad Walerannum) De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati ("On Unleavened and Leavened Sacrifice") and De Sacramentis Ecclesiae ("On the Church's Sacraments") were both written between 1106 and 1107 and are sometimes bound as separate books.[31] Although he seldom asked others to pray for him, two of his letters to hermits do so, "evidence of his belief in their spiritual prowess".[209] His letters of guidance—one to Hugh, a hermit near Caen, and two to a community of lay nuns—endorse their lives as a refuge from the difficulties of the political world with which Anselm had to contend.[209]

Many of Anselm's letters contain passionate expressions of attachment and affection, often addressed "to the beloved lover" (dilecto dilectori). While there is wide agreement that Anselm was personally committed to the monastic ideal of celibacy, some academics such as McGuire[210] and Boswell[211] have characterized these writings as expressions of a homosexual inclination.[212] The general view, expressed by Olsen[213] and Southern, sees the expressions as representing a "wholly spiritual" affection "nourished by an incorporeal ideal".[214]

Legacy

Two biographies of Anselm were written shortly after his death by his chaplain and secretary Eadmer (Vita et Conversatione Anselmi Cantuariensis) and the monk Alexander (Ex Dictis Beati Anselmi).[30] Eadmer also detailed Anselm's struggles with the English monarchs in his history (Historia Novorum). Another was compiled about fifty years later by John of Salisbury at the behest of Thomas Becket.[207] The historians William of Malmesbury, Orderic Vitalis, and Matthew Paris all left full accounts of his struggles against the second and third Norman kings.[207]

Anselm's students included Eadmer, Alexander, Gilbert Crispin, Honorius Augustodunensis, and Anselm of Laon. His works were copied and disseminated in his lifetime and exercised an influence on the Scholastics, including Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham.[142] His thoughts have guided much subsequent discussion on the procession of the Holy Spirit and the atonement. His work also anticipates much of the later controversies over free will and predestination.[58] An extensive debate occurred—primarily among French scholars—in the early 1930s about "nature and possibility" of Christian philosophy, which drew strongly on Anselm's work.[142]

Modern scholarship remains sharply divided over the nature of Anselm's episcopal leadership. Some, including Fröhlich[215] and Schmitt,[216] argue for Anselm's attempts to manage his reputation as a devout scholar and cleric, minimizing the worldly conflicts he found himself forced into.[216] Vaughn[217] and others argue that the "carefully nurtured image of simple holiness and profound thinking" was precisely employed as a tool by an adept, disingenuous political operator,[216] while the traditional view of the pious and reluctant church leader recorded by Eadmer—one who genuinely "nursed a deep-seated horror of worldly advancement"—is upheld by Southern[218] among others.[209][216]

Veneration

Anselm's hagiography records that, when a child, he had a miraculous vision of God on the summit of the Becca di Nona near his home, with God asking his name, his home, and his quest before sharing bread with him. Anselm then slept, awoke returned to Aosta, and then retraced his steps before returning to speak to his mother.[24]

Anselm's canonization was requested of Pope Alexander III by Thomas Becket at the Council of Tours in 1163.[207] He may have been formally canonized before Becket's murder in 1170: no record of this has survived but he was subsequently listed among the saints at Canterbury and elsewhere. It is usually reckoned, however, that his cult was only formally sanctioned by Pope Alexander VI in 1494[93][219] or 1497[135] at the request of Archbishop Morton.[135] His feast day is commemorated on the day of his death, 21 April, by the Catholic Church, much of the Anglican Communion,[30] and some forms of High Church Lutheranism. The location of his relics is uncertain. His most common attribute is a ship, representing the spiritual independence of the church.

Anselm was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Clement XI in 1720;[25] he is known as the doctor magnificus ("Magnificent Doctor")[40] or the doctor Marianus ("Marian doctor"). A chapel of Canterbury Cathedral south of the high altar is dedicated to him; it includes a modern stained-glass representation of the saint, flanked by his mentor Lanfranc and his steward Baldwin and by kings William II and Henry I.[220][221] The Pontifical Atheneum of St. Anselm, named in his honor, was established in Rome by Pope Leo XIII in 1887. The adjacent Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino, the seat of the Abbot Primate of the Federation of Black Monks (all the monks under the Rule of St Benedict except the Cistercians and the Trappists), was dedicated to him in 1900. 800 years after his death, on 21 April 1909, Pope Pius X issued the encyclical "Communium Rerum" praising Anselm, his ecclesiastical career, and his writings. In the United States, the Saint Anselm Abbey and its associated college are located in New Hampshire; they held a celebration in 2009 commemorating the 900th anniversary of Anselm's death. In 2015, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, created the Community of Saint Anselm, an Anglican religious order that resides at Lambeth Palace and is devoted to "prayer and service to the poor".[222]

Anselm is remembered in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church on 21 April.[223][224]

Editions of Anselm's works

- Gerberon, Gabriel (1675), Sancti Anselmi ex Beccensi Abbate Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera, nec non Eadmeri Monachi Cantuariensis Historia Novorum, et Alia Opuscula [The Works of St Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury and Former Abbot of Bec, and the History of New Things and Other Minor Works of Eadmer, monk of Canterbury] (in Latin), Paris: Louis Billaine & Jean du Puis (2d ed. published by François Montalant in 1721; republished with errors by Jacques Paul Migne as Vols. CLVIII & CLIX of the 2nd series of his Patrologia Latina in 1853 & 1854)

- Ubaghs, Gerard Casimir [Gerardus Casimirus] (1854), De la Connaissance de Dieu, ou Monologue et Prosloge avec ses Appendices, de Saint Anselme, Archevêque de Cantorbéry et Docteur de l'Église [On Knowing God, or the Monologue and Proslogue with their Appendices, by Saint Anselme, Archbishop of Canterbury and Doctor of the Church] (in Latin and French), Louvain: Vanlinthout & Cie

- Ragey, Philibert (1883), Mariale seu Liber precum Metricarum ad Beatam Virginem Mariam Quotidie Dicendarum (in Latin), London: Burns & Oates

- Deane, Sidney Norton (1903), St. Anselm: Proslogium, Monologium, an Appendix in Behalf of the Fool by Gaunilon, and Cur Deus Homo with an Introduction, Bibliography, and Reprints of the Opinions of Leading Philosophers and Writers on the Ontological Argument, Chicago: Open Court Publishing Co. (Republished and expanded as St. Anselm: Basic Writings in 1962)

- Webb, Clement Charles Julian (1903), The Devotions of Saint Anselm Archbishop of Canterbury, London: Methuen & Co. (Translating the Proslogion, the "Meditations", and some prayers and letters)

- Schmitt, Franz Sales [Franciscus Salesius] (1936), "Ein neues unvollendetes Werk des heilige Anselm von Canterbury [A New Unfinished Work by St Anselm of Canterbury]", Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie und Theologie des Mittelalters [Contributions on the History of the Philosophy and Theology of the Middle Ages], Vol. XXXIII, No. 3 (in Latin and German), Munster: Aschendorf, pp. 22–43

- Henry, Desmond Paul (1964), The De Grammatico of St Anselm (in Latin and English), South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press

- Charlesworth, Maxwell John (1965), St. Anselm's Proslogion (in Latin and English), South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press

- Schmitt, Franz Sales [Franciscus Salesius] (1968), S. Anselmi Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera Omnia [The Complete Works of St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury] (in Latin), Stuttgart: Friedrich Fromann Verlag

- Southern, Richard W.; et al. (1969), Memorials of St. Anselm (in Latin and English), Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Ward, Benedicta (1973), The Prayers and Meditations of Saint Anselm, New York: Penguin Books

- Hopkins, Jasper; et al. (1976), Anselm of Canterbury, Edwin Mellen (A reprint of earlier separate translations; republished by Arthur J. Banning Press as The Complete Philosophical and Theological Treatises of Anselm of Canterbury in 2000) (Hopkins's translations available here .)

- Fröhlich, Walter (1990–1994), The Letters of Saint Anselm of Canterbury (in Latin and English), Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications

- Davies, Brian; et al. (1998), Anselm of Canterbury: The Major Works, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Williams, Thomas (2007), Anselm: Basic Writings, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing (A reprint of earlier separate translations)

See also

- Fides quaerens intellectum

- Other Anselms and Saint Anselms

- Saint Anselm's, various places named in Anselm's honor

- Cur Deus Homo

- Cluny, Gregorian Reform, and clerical celibacy

- Investiture Controversy

- Canterbury–York dispute

- Saint Anselm of Canterbury, patron saint archive

- Slavery in the British Isles

- Scholasticism

- Existence of God

Notes

- An entry concerning Anselm's parents in the records of Christ Church in Canterbury leaves open the possibility of a later reconciliation.[15]

- Anselm did not publicly condemn the Crusade but replied to an Italian whose brother was then in Asia Minor that he would be better off in a monastery instead. Southern summarized his position in this way: "For him, the important choice was quite simply between the heavenly Jerusalem, the true vision of Peace signified by the name Jerusalem, which was to be found in the monastic life, and the carnage of the earthly Jerusalem in this world, which under whatever name was nothing but a vision of destruction".[81]

- Direct knowledge of Plato's works was still quite limited. Calcidius's incomplete Latin translation of Plato's Timaeus was available and a staple of 12th-century philosophy but "seems not to have interested" Anselm.[140]

- Latin: Neque enim quaero intelligere ut credam, sed credo ut intelligam. Nam et hoc credo, quia, nisi credidero, non intelligam.

- Other examples include "The Christian ought to go forth to understanding through faith, not journey to faith through understanding" (Christianus per fidem debet ad intellectum proficere, non per intellectum ad fidem accedere) and "The correct order demands that we believe the depths of the Christian faith before we presume to discuss it with reason" (Rectus ordo exigit, ut profunda Christianae fidei credamus, priusquam ea praesumamus ratione discutere).[93]

- Latin: Negligentise mihi esse videtur, si, postquam confirmatius in fide, non studemus quod credimus, intelligere.

- Anselm requested the works be retitled in a letter to Hugh, Archbishop of Lyon,[153] but didn't explain why he chose to use the Greek forms. Logan conjectures it may have derived from Anselm's secondhand acquaintance with Stoic terms used by St Augustine and by Martianus Capella.[152]

- Although the Latin meditandus is usually translated as "meditation", Anselm was not using the term in its modern sense of "self-reflection" or "consideration" but instead as a philosophical term of art which described the more active process of silently "reaching out into the unknown".[155]

- See note above on the renaming of Anselm's works.

- As by Thomas Williams.[167]

- Various scholars have disputed the use of the term "ontological" in reference to Anselm's argument. A list up to his own time is provided by McEvoy.[168]

- Variations of the argument were elaborated and defended by Duns Scotus, Descartes, Leibniz, Gödel, Plantinga, and Malcolm. In addition to Gaunilo, other notable objectors to its reasoning include Thomas Aquinas and Immanuel Kant, with the most thorough analysis having been done by Zalta and Oppenheimer.[175][176][177]

- The title is a reference to Anselm's invocation of the Psalms' "The fool has said in his heart, 'There is no God'".[179][180] Gaunilo offers that, if Anselm's argument were all that supported the existence of God, the fool would be correct in rejecting his reasoning.[167]

- Southern[184] and Thomas Williams[31] date it to 1059–60, while Marenbon places it "probably... shortly after" 1087.[140]

Citations

- "Holy Men and Holy Women" (PDF). Churchofengland.org.

- "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Charlesworth (2003), pp. 23–24.

- "Saint Anselm of Canterbury". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Rule (1883), p. 2–3.

- Rule (1883), p. 1–2.

- Southern (1990), p. 7.

- Previté-Orton, Charles William (1912). The Early History of the House of Savoy: 1000-1233. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 155. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Kirsch, Johann Peter (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Denis Mack Smith (1989). Italy and Its Monarchy. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300051328.

- Villari, Luigi (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–257.

- Rule (1883), p. 1–4.

- Southern (1990), p. 8.

- EB (1878), p. 91.

- Robson (1996).

- Joseph-Gabriel Rivolin, Anselme d'Aoste, notes bio-bibliographiques.

- ODCC (2005), p. 73.

- Rule (1883), p. 1.

- Joseph-Gabriel Rivolin, Anselme d'Aoste, notes bio-bibliographiques.

- Rule (1883), p. 2.

- Rule (1883), p. 4–7.

- Rule (1883), p. 7–8.

- Southern (1990), p. 9.

- Rule (1883), p. 12–14.

- Butler (1864).

- Wilmot-Buxton (1915), Ch. 3.

- Rambler (1853), p. 365–366.

- Rambler (1853), p. 366.

- Charlesworth (2003), p. 9.

- IEP (2006), §1.

- SEP (2007), §1.

- Southern (1990), p. 32.

- Charlesworth (2003), p. 10.

- Rambler (1853), pp. 366–367.

- Rambler (1853), p. 367–368.

- Rambler (1853), p. 368.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 282.

- Charlesworth (2003), p. 15.

- Rambler (1853), p. 483.

- PEF (2000).

- Vaughn (1975), p. 281.

- Rambler (1853), p. 369.

- Charlesworth (2003), p. 16.

- ODCC (2005), p. 74.

- Rambler (1853), p. 370.

- Southern (1990), p. 189.

- Rambler (1853), p. 371.

- Barlow (1983), pp. 298–299.

- Southern (1990), p. 189–190.

- Southern (1990), p. 191–192.

- Barlow (1983), p. 306.

- Vaughn (1974), p. 246.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 286.

- Vaughn (1974), p. 248.

- Charlesworth (2003), p. 17.

- Boniface (747), Letter to Cuthbert.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 683.

- CE (1907).

- Vaughn (1988), p. 218.

- Vaughn (1978), p. 357.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 293.

- EB (1878), pp. 91–92.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 82.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 83.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 298.

- Duggan (1965), pp. 98–99.

- Willis (1845), p. 38.

- Willis (1845), pp. 17–18.

- Cook (1949), p. 49.

- Willis (1845), pp. 45–47.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 287.

- Rambler (1853), p. 482.

- Wilmot-Buxton (1915), p. 136.

- Powell & al. (1968), p. 52.

- Vaughn (1987), pp. 182–185.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 289.

- Cantor (1958), p. 92.

- Barlow, Frank (1983). William Rufus. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04936-5, pp. 342-344

- Davies (1874), p. 73.

- Rambler (1853), p. 485.

- Southern (1990), p. 169.

- Cantor (1958), p. 97.

- Vaughn (1987), p. 188.

- Vaughn (1987), p. 194.

- Potter (2009), p. 47.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 291.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 292.

- Vaughn (1978), p. 360.

- Southern (1990), p. 279.

- Southern (1963).

- Kidd (1927), pp. 252–3.

- Fortescue (1907), p. 203.

- EB (1878), p. 92.

- Southern (1990), p. 280.

- Southern (1990), p. 281.

- Sharpe, Richard (2009). "Anselm as author: Publishing in the late eleventh century" (PDF). The Journal of Medieval Latin. 19: 1–87. doi:10.1484/J.JML.1.100545. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2016.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 63.

- Southern (1990), p. 291.

- Hollister (1983), p. 120.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 67.

- Hollister (2003), pp. 137–138.

- Hollister (2003), pp. 135–136.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 295.

- Hollister (2003), pp. 128–129.

- Partner (1973), pp. 467–475, 468.

- Boswell (1980), p. 215.

- Crawley (1910).

- Rambler (1853), p. 489–91.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 71.

- ODCC (2005), p. 74.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 74.

- Charlesworth (2003), pp. 19–20.

- Rambler (1853), p. 496–97.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 75.

- Vaughn (1978), p. 367.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 76.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 77.

- Rambler (1853), p. 497–98.

- Vaughn (1975), pp. 296–297.

- Vaughn (1980), p. 80.

- Vaughn (1975), p. 297.

- Cross, Michael, "Altar in St Anselm Chapel", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 30 June 2015

- "St Anselm's Chapel Altar", Waymarking, Seattle: Groundspeak, 28 April 2012, retrieved 30 June 2015

- Rambler (1853), p. 498.

- Willis (1845), p. 46.

- Ollard & al. (1931), App. D, p. 21.

- HMC (1901), p. 227–228.

- A letter of 9 January 1753 by "S.S." (probably Samuel Shuckford but possibly Samuel Stedman)[126] to Thomas Herring.[127]

- Ollard & al. (1931), App. D, p. 20.

- HMC (1901), p. 226.

- A letter of 23 December 1752 by Thomas Herring to John Lynch.[130]

- HMC (1901), p. 227.

- A letter of 6 January 1753 by Thomas Herring to John Lynch.[132]

- HMC (1901), p. 229–230.

- A letter of 31 March 1753 by P. Bradley to Count Perron.[134]

- HMC (1901), p. 230–231.

- A letter of 16 August 1841 by Lord Bolton, possibly to W. R. Lyall.[136]

- Davies & al. (2004), p. 2.

- IEP (2006), Introduction.

- Marenbon (2005), p. 170.

- Logan (2009), p. 14.

- IEP (2006), §2.

- Marenbon (2005), p. 169–170.

- Hollister (1982), p. 302.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 82.

- Schaff (2005).

- SEP (2007).

- Anselm of Canterbury, Cur Deus Homo, Vol. I, §2.

- Anselm of Canterbury, De Fide Trinitatis, §2.

- IEP (2006), §3.

- Davies & al. (2004), p. 201.

- Logan (2009), p. 85.

- Anselm of Canterbury, Letters, No. 109.

- Luscombe (1997), p. 44.

- Logan (2009), p. 86.

- Gibson (1981), p. 214.

- Logan (2009), p. 21.

- Logan (2009), p. 21–22.

- EB (1878), p. 93.

- Anselm of Canterbury, Monologion, p. 7, translated by Sadler.[150]

- SEP (2007), §2.1.

- IEP (2006).

- SEP (2007), §2.2.

- Rogers (2008), p. 8.

- IEP (2006), §6.

- Forshall (1840), p. 74.

- SEP (2007), §2.3.

- McEvoy (1994).

- IEP (2006), §4.

- Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, p. 104, translated by Sadler.[169]

- SEP (2007), §3.1.

- SEP (2007), §3.2.

- Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, p. 115, translated by Sadler.[169]

- Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, p. 117, translated by Sadler.[169]

- Zalta & al. (1991).

- Zalta & al. (2007).

- Zalta & al. (2011).

- IEP (2006), §5.

- Psalm 14:1.

- Psalm 53:1.

- Klima (2000).

- Wolterstorff (1993).

- Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, p. 103, translated by Sadler.[169]

- Southern (1990), p. 65.

- IEP (2006), §8.

- SEP (2007), §4.1.

- IEP (2006), §9.

- Anselm of Canterbury, De Veritate, p. 185, translated by Sadler.[187]

- SEP (2007), §4.2.

- IEP (2006), §11.

- SEP (2007), §4.3.

- IEP (2006), §7.

- IEP (2006), §3 & 7.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 83.

- Fulton (2002), p. 176.

- Fulton (2002), p. 178.

- Foley (1909).

- Foley (1909), pp. 256–7.

- Janaro (2006), p. 51.

- Janaro (2006), p. 52.

- IEP (2006), §12.

- Anselm of Canterbury, De Concordia, p. 254, translated by Sadler.[201]

- Holland (2012), p. 43.

- IEP (2006), §13.

- Dinkova-Bruun (2015), p. 85.

- IEP (2006), §14.

- Rambler (1853), p. 361.

- Southern (1990), p. 396.

- Hughes-Edwards (2012), p. 19.

- McGuire (1985).

- Boswell (1980), pp. 218–219.

- Doe (2000), p. 18.

- Olsen (1988).

- Southern (1990), p. 157.

- Fröhlich (1990), pp. 37–52.

- Gale (2010).

- Vaughn (1987).

- Southern (1990), pp. 459–481.

- Southern (1990), p. xxix.

- "The Stained Glass of Canterbury, Modern Edition", A Clerk of Oxford, 27 April 2011, retrieved 29 June 2015

- Thistleton, Alan, "St Anselm Window", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 30 June 2015

- Lodge, Carey (18 September 2015). "Archbishop Welby launches monastic community at Lambeth Palace". Christian Today. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 1 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-234-7.

References

- "Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109)", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006, retrieved 30 June 2015

- "St Anselm", The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 73–75, ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3

- "Reviews: St. Gregory and St. Anselm: Saint Anselme de Cantorbery. Tableau de la vie monastique, et de la lutte du pouvoir spirituel avec le pouvoir temporel au onzième siècle. Par M.C. de Remusat. Didier, Paris, 1853", The Rambler, A Catholic Journal and Review, Vol. XII, No. 71 & 72, London: Levey, Robson, & Franklyn for Burns & Lambert, 1853, pp. 360–374, 480–499

- "Saint Anselm", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 2000 [Revised 2007]

- "Anselm of Canterbury" (PDF), Universal Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Lublin: Polish Thomas Aquinas Association [Originally published in Polish as Powszechna Encyklopedia Filozofii]

- Anselm of Canterbury, De Concordia (in Latin), (Schmitt edition)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Barlow, Frank (1983), William Rufus, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04936-5

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 91–93

- Boniface (747), Letter to Cuthbert, archbishop of Canterbury, translated by Talbot

- Boswell, John (1980), Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century, University Of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-06711-4

- Butler, Alban (1864), "St Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury", The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, Vol. VI, D. & J. Sadlier & Co.

- Cantor, Norman F. (1958), Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture in England 1089–1135, Princeton: Princeton University Press, OCLC 2179163

- Charlesworth, Maxwell J. (2003), "Introduction", St. Anselm's Proslogion with A Reply on Behalf of the Fool by Gaunilo and the Author's Reply to Gaunilo, South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press (Originally published 1965)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–83.

- Cook, G.H. (1949), Portrait of Canterbury Cathedral, London: Phoenix House

- Crawley, John J. (1910), Lives of the Saints, John J. Crawley & Co.

- Croset-Mouchet, Joseph, Saint Anselme (d'Aoste), archevêque de Cantorbéry : Histoire de sa vie et de son temps.

- Davies, Brian; et al. (2004), The Cambridge Companion to Anselm, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-00205-2

- Davies, James (1874), History of England from the Death of "Edward the Confessor" to the Death of John, (1066–1216) A.D., London: George Philip & Son

- Dinkova-Bruun, Greti (2015), "Nummus Falsus: The Perception of Counterfeit Money in the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Century", Money and the Church in Medieval Europe, 1000–1200: Practice, Morality, and Thought, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 77–92, ISBN 9781472420992

- Doe, Michael (2000), Seeking the Truth in Love: The Church and Homosexuality, Darton, Longman and Todd, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-232-52399-7

- Duggan, Charles (1965), "From the Conquest to the Death of John", The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, [Reprinted 1999 by Sutton Publishing], pp. 63–116, ISBN 0-7509-1947-7

- Foley, George C. (1909), Anselm's Theory of the Atonement, London: Longmans, Green, & Co.

- Forshall, Josiah, ed. (1840), Catalogue of Manuscripts in the British Museum, New Series Vol. I, Pt. II: The Burney Manuscripts, London: British Museum

- Fortescue, Adrian H.T.K. (1907), The Orthodox Eastern Church, Catholic Truth Society, ISBN 9780971598614

- Fröhlich, Walter (1990), "Introduction", The Letters of Saint Anselm of Canterbury, Vol. I, Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications

- Fulton, Rachel (2002), From Judgment to Passion: Devotion to Christ & the Virgin Mary, 800–1200, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-12550-X

- Gale, Colin (5 July 2010), "Treasures in Earthen Vessels: Treasures from Lambeth Palace Library", Fulcrum, London: Fulcrum Anglican

- Gibson, Margaret (1981), "The Opuscula Sacra in the Middle Ages", Boethius: His Life, Thought, and Influence, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 214–234

- Historical Manuscripts Commission (1901), Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections, Vol. I Berwick-upon-Tweed, Burford, and Lostwithiel Corporations; the Counties of Wilts and Worcester; the Bishop of Chichester; and the Deans and Chapters of Chichester, Canterbury, and Salisbury, London: Mackie & Co. for His Majesty's Stationery Office

- Holland, Richard A. Jr. (2012), "Anselm", God, Time, and the Incarnation, Eugene: Wipf & Stock, pp. 42–44, ISBN 978-1-61097-729-6

- Hollister, C. Warren (1982), Medieval Europe: A Short History, New York: John Wiley & Sons

- Hollister, C. Warren (1983), The Making of England: 55 B.C. to 1399, Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company

- Hollister, C. Warren (2003), Henry I, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-09829-7

- Hughes-Edwards, Mari (2012), Reading Medieval Anchoritism: Ideology and Spiritual Practices, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, ISBN 978-0-7083-2505-6

- Janaro, John (Spring 2006), "Saint Anselm and the Development of the Doctrine of the Immaculate Conception: Historical and Theological Perspectives" (PDF), The Saint Anselm Journal, 3 (2): 48–56, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2010, retrieved 23 April 2009

- Kent, William (1907), , in Herbermann, Charles (ed.), Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 1, New York: Robert Appleton Company

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kidd, B.J. (1927), The Churches of Eastern Christendom: From A.D. 451 to the Present Time, [reprinted by Routledge 2013], ISBN 9781136212789

- Klima, Gyula (2000), "Saint Anselm's Proof: A Problem of Reference, Intentional Identity and Mutual Understanding", Medieval Philosophy and Modern Times (Proceedings of "Medieval and Modern Philosophy of Religion", Boston University, 25–27 August 1992), Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 69–88