Tawa hallae

Tawa (named after the Hopi word for the Puebloan sun god) is a genus of possible basal theropod dinosaurs from the Late Triassic period.[1] The fossil remains of Tawa hallae, the type and only species were found in the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, US. Its discovery alongside the relatives of Coelophysis and Herrerasaurus supports the hypothesis that the earliest dinosaurs arose in Gondwana during the early Late Triassic period in what is now South America, and radiated from there around the globe.[2] The specific name honours Ruth Hall, founder of the Ghost Ranch Museum of Paleontology.[3]

| Tawa hallae Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

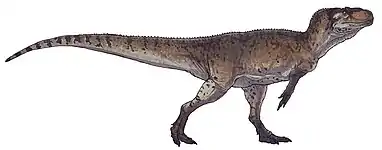

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda (?) |

| Genus: | †Tawa Nesbitt et al., 2009 |

| Species: | †T. hallae |

| Binomial name | |

| †Tawa hallae Nesbitt et al., 2009 | |

Description

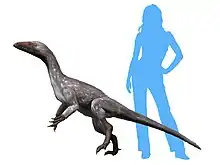

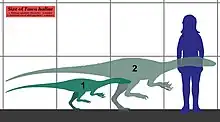

Tawa was estimated to have been 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) long as an adult, with a weight of 15 kg (33 lb).[4] Tawa preserves characters that can be associated with different dinosaur taxa. Its skull morphology resembles that of coelophysoids and the ilium approximates that of a herrerasaurid. Like the coelophysoids, Tawa has a kink in its upper jaws, between the maxilla and the premaxilla. With respect to limb proportion, the femur is very long compared to the tibia. A neck vertebral adaptation in Tawa supports the hypothesis that cervical air sacs antedate the origin of the Neotheropoda and may be ancestral for saurischians, and also links the dinosaurs with the evolution of birds. Compared to earlier dinosaurs such as Herrerasaurus and Eoraptor, Tawa had a relatively slender build.[3]

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism or group. According to Nesbitt et al. (2009) Tawa can be distinguished based on the following features: the prootic bones meet on the ventral midline of the endocranial cavity, the anterior tympanic recess is greatly enlarged on the anterior surface of the basioccipital and extends onto the prootic and the parabasisphenoid, a deep recess is present on posterodorsal base of the paroccipital process, a sharp ridge extending dorsoventrally on the middle of the posterior face of the basal tuber, an incomplete ligamental sulcus is present on the posterior side of the femoral head, a semicircular muscle scar/excavation is present on the posterior face of femoral head, a small semicircular excavation on posterior margin of medial posterior condyle of proximal tibia, a "step" is present on the ventral surface of the astragalus, metatarsal I is similar in length to the other metatarsals.[3]

Discovery

Fossils now attributed to Tawa were first discovered in 2004. The holotype, a juvenile individual, cataloged GR 241, consists of a mostly complete, but disarticulated skull, forelimbs, a partial vertebral column, hindlimbs, ribs, and gastralia. The determination was made that this specimen is a juvenile based on the presence of an open braincase and unfused neurocentral sutures. Fossils of at least seven other individuals were also discovered at the site. One of these specimens, cataloged GR 242, is also nearly complete. An isolated femur, GR 244, suggests that adults were at least 30% larger than the juvenile holotype. GR 242 was assigned as a paratype for the genus along with specimens representing a femora, pelvis, and tail (GR 155); and cervical vertebrae (GR 243).[3]

All of these specimens are from the Hayden Quarry, a site in New Mexico, which preserves many fossils of early dinosaurs and their close relatives. They were discovered in gray/green siltstone dating to the Norian stage of the Triassic period, about 215-213 million years ago.[5] Tawa was formally described in 2009 by a group of six American researchers led by Sterling J. Nesbitt of the American Museum of Natural History.[3] At the time of publication in the journal Science, Nesbitt was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas at Austin's Jackson School of Geosciences.[6]

Based on the study of the overlapping material of Dromomeron romeri and Tawa, S. Christopher Bennett proposed that the two taxa were conspecific, forming a single growth series with D. romeri being the juvenile and Tawa being the adult.[7] However, noting prominent differences between their femora which cannot be attributed to variation with age, Rodrigo Müller rejected this proposal in 2017. He further noted that while D. romeri is known from juveniles only, it shares many traits in common with D. gigas, which is known from mature specimens.[5]

Classification

|

The type species is Tawa hallae, which was described in 2009 by Nesbitt et al., and considered more basal than Coelophysis, an early theropod from the Late Triassic. In 2009, Mortimer cautioned that the analysis by Nesbitt et al. was limited because it failed to consider all the characters of the relevant dinosaurs treated by the old analysis (e.g. Guaibasaurus, Panphagia, Sinosaurus, Dracovenator, Lophostropheus, etc.)[8] Tawa was however found to be more advanced than the earliest theropod dinosaurs, Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus,[9] and Staurikosaurus.

Sues et al. (2011) considered Tawa a derived early theropod.[10] A cladistic analysis of Tawa and other early theropods indicate that the Coelophysoidea, a group of early dinosaurs, may be an artificial grouping because Tawa combines classic coelophysoid features with features which appear to be ancestral to the neotheropods. Tawa is believed to be the sister taxon of Neotheropoda, a group of carnivorous dinosaurs which largely bore only three functional digits on their feet.[3]

In 2011, Martinez and colleagues concluded that Tawa was the basalmost coelophysoid,[11] while a second 2011 analysis by paleontologists Martin D. Ezcurra and Stephen L. Brusatte, as well as a follow-up analysis modified with additional data by You Hai-Lu and colleagues in 2014, found Tawa to be a primitive theropod.[12][13] This position for Tawa was also recovered in the large analysis of early dinosaurs by Matthew Baron, David B. Norman and Paul Barrett in 2017.[14]

Cau (2018)[15] and Novas et al. (2021)[16] considered Tawa a non-herrerasaurid herrerasaur, although the first study placed Herrerasauria outside Dinosauria and the second placed it in Saurischia.

Paleoecology

The Hayden Quarry at Ghost Ranch belongs to the lower portion of the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle Formation in New Mexico. The discovery of Tawa alongside the relatives of Coelophysis and Herrerasaurus supports the hypothesis that the earliest dinosaurs arose in Gondwana during the Late Triassic period in what is now South America, and radiated around the globe from there.

Ghost Ranch was located close to the equator 200 million years ago, and had a warm, monsoon-like climate with heavy seasonal precipitation. Hayden Quarry, an excavation site at Ghost Ranch, has yielded a diverse collection of fossil material that included the first evidence of dinosaurs and less-advanced dinosauromorphs from the same time period. The discovery indicates that the two groups lived together during the early Triassic period 235 million years ago.[17] Tawa's paleoenvironment included various archosauriforms such as crocodylomorphs, "rauisuchians", phytosaurs, and dinosauriforms like Dromomeron, Chindesaurus, Eucoelophysis, and possibly Coelophysis.[18]

Based on their review of the early carnivorous dinosaur fauna from Ghost Ranch and the Ischigualasto Formation Nesbit et al. (2009) observed that each was descended from a separate lineage, and inferred that the "South American" protocontinent Gondwana was the ancestral range for basal dinosaurs. Nesbit et al. (2009) went on to note that dinosaurs left their ancestral range in Gondwana and 200 million years ago they dispersed across the adjoined continents of Pangea.[3]

Nesbit et al. (2009) noted that repeated flooding events collected vertebrate bones, carcasses, and plant material from the landscape surface, possibly in hyperconcentrated flows, and deposited them at what is now Hayden Quarry. It was observed that these flooding events were separated by intervals where there was standing water and weakly developed, poorly drained (hydromorphic) soil formation. The Tawa specimens were very well preserved which suggests that they were buried extremely soon after dying.[3]

See also

References

- Maffly, Brian (December 10, 2009), "New Mexico find sheds light on early dinosaur dispersal", Salt Lake Tribune, archived from the original on December 13, 2009

- "New T. Rex Cousin Suggests Dinosaurs Arose in S. America", National Geographic, December 10, 2009

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Smith, Nathan D.; Irmis, Randall B.; Turner, Alan H.; Downs, Alex; Norell, Mark A. (11 December 2009). "A Complete Skeleton of a Late Triassic Saurischian and the Early Evolution of Dinosaurs". Science. 326 (5959): 1530–1533. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1530N. doi:10.1126/science.1180350. PMID 20007898. S2CID 8349110.

- Paul, G.S. (2010). "Theropods". The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780691167664.

- Müller, R.T. (2017). "Are the dinosauromorph femora from the Upper Triassic of Hayden Quarry (New Mexico) three stages in a growth series of a single taxon?" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 89 (2): 835–839. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201720160583. PMID 28489198.

- Airhart, Marc (December 10, 2009), "New Meat-Eating Dinosaur Alters Evolutionary Tree", Jackson School of Geosciences, archived from the original on March 10, 2010

- Bennett, S.C. (2013). "A Rebuttal to Nesbitt's and Hone's "An external mandibular fenestra and other archosauriform characteristics in basal pterosaurs"" (PDF). International Symposium on Pterosaurs: 19–22.

- DML: http://dml.cmnh.org/2009Dec/msg00122.html

- Harmon, Katherine (December 10, 2009), "Newly Discovered T. Rex Relative Fleshes Out Early Dino Evolution", Scientific American

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Berman, David S; Henrici, Amy C. (22 November 2011). "A late-surviving basal theropod dinosaur from the latest Triassic of North America". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1723): 3459–3464. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0410. PMC 3177637. PMID 21490016.

- Martinez, Sereno; Alcober, Columbi; Renne, Montanez; Currie (2011). "A basal dinosaur from the dawn of the dinosaur era in Southwestern Pangaea". Science. 331 (6014): 206–210. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..206M. doi:10.1126/science.1198467. hdl:11336/69202. PMID 21233386. S2CID 33506648.

- Ezcurra, M.D.; Brusatte, S.L. (2011). "Taxonomic and phylogenetic reassessment of the early neotheropod dinosaur Camposaurus arizonensis from the Late Triassic of North America". Palaeontology. 54 (4): 763–772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01069.x.

- You, H.-L.; Azuma, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.-M.; Dong, Z.-M. (2014). "The first well-preserved coelophysoid theropod dinosaur from Asia". Zootaxa. 3873 (3): 233–249. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3873.3.3. PMID 25544219.

- Baron, M.G.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution". Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513. S2CID 205254710.

- Cau, Andrea (2018). "The assembly of the avian body plan : a 160-million-year long process" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 57 (1): 1–25. S2CID 44078918.

- Novas, Fernando E.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Temp Müller, Rodrigo; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Langer, Max C. (October 2021). "Review of the fossil record of early dinosaurs from South America, and its phylogenetic implications". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 110: 103341. Bibcode:2021JSAES.11003341N. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103341.

- Braginetz, Donna. "A new species of dinosauromorph (lower left) was among the mixed assemblage of dinosaurs and dinosauromorphs found at Hayden Quarry in Ghost Ranch, N.M." American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- Irmis et al. 2007

.jpg.webp)