Tehran

Tehran (/tɛəˈræn, -ˈrɑːn, ˌteɪ-/; Persian: تهران Tehrân [tehˈɾɒːn] ⓘ) is the capital and most populous city of Iran, capital of Tehran province and Tehran county. Tehran city had a population of 9,039,000 in the estimate of 2022 and according to the 2018 estimate of the United Nations, it is the 34th most populous city in the world and the most populous city in West Asia. Tehran metropolis is the second most populated metropolis in the Middle East.[6]

Tehran

تهران | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

| Coordinates: 35°41′21″N 51°23′20″E | |

| Country | Iran |

| Province | Tehran |

| County | Tehran Rey Shemiranat |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alireza Zakani |

| • City Council Chairman | Mehdi Chamran |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 615 km2 (237 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,235 km2 (863 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 900 to 1,830 m (2,952 to 6,003 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Density | 13,800/km2 (36,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 9,039,000[4] |

| • Metro | 15,800,000[5] |

| • Population rank in Iran | 1st |

| Demonym | Tehrani (en) |

| Time zone | UTC+03:30 (IRST) |

| Area codes | +98 21 |

| Climate | BSk/Csa |

| Website | tehran.ir |

In the classical antiquity, part of the territory of present-day Tehran was occupied by Rhages (now Ray), a prominent Median city[7] destroyed in the medieval Arab, Turkic, and Mongol invasions. Modern Ray was absorbed into the metropolitan area of Greater Tehran.

Tehran was first chosen as the capital of Iran by Agha Mohammad Khan of the Qajar dynasty in 1786, because of its proximity to Iran's territories in the Caucasus, then separated from Iran in the Russo-Iranian Wars, to avoid the vying factions of the previously ruling Iranian dynasties. The capital has been moved several times throughout history, however, and Tehran became the 32nd capital of Persia. Large-scale construction works began in the 1920s, and Tehran became a destination for mass migrations from all over Iran since the 20th century.[8]

Tehran is home to many historical sites, including the royal complexes of Golestan, Sa'dabad, and Niavaran, where the last two dynasties of the former Imperial State of Iran were seated. Tehran's landmarks include the Azadi Tower, a memorial built under the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1971 to mark the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire, the Milad Tower, the world's sixth-tallest self-supporting tower, completed in 2007, and the Tabiat Bridge, completed in 2014.[9]

Most of the population are Persian,[10][11] with roughly 99% of them speaking the Persian language, alongside other ethnolinguistic groups in the city which became assimilated.[12]

Tehran is served by Imam Khomeini International Airport, alongside the domestic Mehrabad Airport, a central railway station, Tehran Metro, a bus rapid transit system, trolleybuses, and a large network of highways.

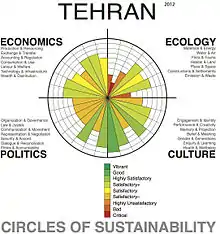

Plans to relocate the capital from Tehran to another area due to air pollution and earthquakes have not been approved so far. A 2016 survey of 230 cities across the globe by Mercer ranked Tehran 203rd for quality of life.[13] According to the Global Destinations Cities Index in 2016, Tehran is among the top ten fastest growing destinations.[14] Tehran City Council declared 6 October the Tehran Day in 2016, celebrating the date when in 1907 the city officially became the capital of Iran.[15]

Etymology

Various theories on the origin of the name Tehran have been put forward.

Iranian linguist Ahmad Kasravi, in an article "Shemiran-Tehran", suggested that Tehran and Kehran mean "the warm place", and Shemiran means "the cool place". He listed cities with the same base and suffix and studied the components of the word in ancient Iranian languages, and came to the conclusion that Tehran and Kehran meant the same thing in different Iranian language families, as the consonants "t" and "k" are close to each other in such languages. He also provided evidence that cities named "Shemiran" were colder than those named "Tehran" or "Kehran". He considered other theories not considering the ancient history of Iranian languages such as "Tirgan" theory and "Tahran" theory folk etymology.[16]

The official City of Tehran website says that "Tehran" comes from the Persian words tah meaning "end", or "bottom", and ran meaning "[mountain] slope"—literally, the bottom of the mountain (ته کوه). Given Tehran's position at the foot of the Alborz mountains, this seems plausible.[17]

The most interesting toponymical theory of the name Tehran has been suggested by Zana Piranshahri (Dana Pishdar), the Iranian linguist residing in Norway.

According to Dana Pishdar, the etymological root of the name Tehran should be searched for in the ancient Iranic languages such as Median and Avestan. Because in the pre-Islamic era, the city of Rey and the area of Tehran were the largest cities of the Media region, and also in Zoroastrian era, it was considered a holy city and was headquarters of a theocratic government similar to the modern Vatican state; this suggestion does not sound illogical.

In the opinion of Dana Pishdar, the name of Tehran consists of the two lexical elements, teh and ran. According to Pishdar, teh in ancient Median languages means "honeyberry" and ran means "foothills". Honeyberry trees used to grow in the northern parts of Tehran province. It is also mentioned in the Dehkhoda dictionary and Dehkhoda explains it in this way: teh is a name that in Shemiranat and around Tehran is applied to the "honeyberry" tree.

So according to Zana Piranshahri, the word Tehran means a place where the "honeyberry" tree grows. Also the suffix ran is visible in many of the names of districts and villages of modern Tehran that are not unrelated to each other, such as Shemiran, Niavaran, Jamaran, Qasran and Shahran. In the Avestan language and also in the book of Avesta ran has had the meaning of "foothills" and "plain," which is still related to the name of the Rey city. The Zoroastrian Medes called their largest and most important town Rhaga or Rey, meaning the town which is situated in the plain and on a foothill. Therefore, the words "Rey" and "Ran" mean foothills, and the toponymic reason for this is the geographical position of Rey and Tehran, because both are located on foothills and in a plain.[18]

In English, it was formerly spelt "Teheran".[19]

History

Archaeological remains from the ancient city of Ray suggest that settlement in Tehran dates back over 6,000 years.[20]

Classical era

Tehran is in the historical Media region of (Old Persian: 𐎶𐎠𐎭 Māda) in northwestern Iran. By the time of the Median Empire, part of present-day Tehran was a suburb of the prominent Median city of Rhages (Old Persian: 𐎼𐎥𐎠 Ragā). In the Avesta's Videvdat (i, 15), Rhages is mentioned as the 12th sacred place created by Ohrmazd.[21] In Old Persian inscriptions, Rhages appears as a province (Bistun 2, 10–18). From Rhages, Darius I sent reinforcements to his father Hystaspes, who was putting down a rebellion in Parthia (Bistun 3, 1–10).[21] Some Middle Persian texts give Rhages as the birthplace of Zoroaster,[22] although modern historians generally place the birth of Zoroaster in Khorasan Province.

Mount Damavand, the highest peak of Iran, which is located near Tehran, is an important location in Ferdowsi's Šāhnāme,[23] an Iranian epic poem based on the ancient legends of Iran. It appears in the epics as the homeland of the protoplast Keyumars, the birthplace of King Manuchehr, the place where King Fereydun bound the dragon fiend Aždahāk (Bivarasp), and the place where Arash shot his arrow.[23]

Medieval period

In 641, during the reign of the Sasanian Empire, Yazdgerd III issued his last appeal to the nation from Rhages, before fleeing to Khorasan.[21] Rhages was dominated by the Parthian House of Mihran, and Siyavakhsh—the son of Mehran, the son of Bahram Chobin—who resisted the seventh-century Muslim invasion of Iran.[21] Because of this resistance, when the Arabs captured Rhages, they ordered the town destroyed and rebuilt anew by traitor aristocrat Farrukhzad.[21]

In the ninth century, Tehran was a well-known village, but less so than the city of Rhages, flourishing nearby. Rhages was described in detail by tenth-century Muslim geographers.[21] Despite the interest that Arabian Baghdad displayed in Rhages, the number of Arabs in the city remained insignificant and the population mainly consisted of Iranians of all classes.[21][24]

The Oghuz Turks invaded Rhages in 1035 and again in 1042, but the city was recovered under the Seljuks and the Khwarezmians.[21] Medieval writer Najm od Din Razi declared the population of Rhages about 500,000 before the Mongol invasion. In the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Rhages, laid the city to ruins, and massacred many of its inhabitants.[21] Others escaped to Tehran.

In July 1404, Castilian ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo visited Tehran on a journey to Samarkand, the capital of Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur, the ruler of Iran at the time. He described it in his diary as an unwalled region.

Early modern era

Italian traveler Pietro della Valle passed through Tehran overnight in 1618, and in his memoirs called the city Taheran. English traveler Thomas Herbert entered Tehran in 1627, and mentioned it as Tyroan. Herbert stated that the city had about 3,000 houses.[25]

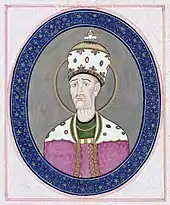

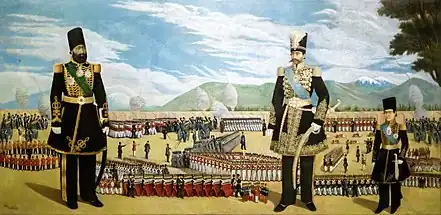

In the early 18th century, Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty ordered a palace and a government office built in Tehran, possibly to declare the city his capital; but he later moved his government to Shiraz. Eventually, Qajar king Agha Mohammad Khan chose Tehran as the capital of Iran in 1786.[26]

Agha Mohammad Khan's choice of his capital was based on a similar concern for the control of both northern and southern Iran.[26] He was aware of the loyalties of the inhabitants of former capitals Isfahan and Shiraz to the Safavid and Zand dynasties respectively, and was wary of the power of the local notables in these cities.[26] Thus, he probably viewed Tehran's lack of a substantial urban structure as a blessing, because it minimized the chances of resistance to his rule by the notables and by the general public.[26] Moreover, he had to remain within close reach of Azerbaijan and Iran's integral northern and southern Caucasian territories[26]—at that time not yet irrevocably lost per the treaties of Golestan and Turkmenchay to the neighboring Russian Empire—which would follow in the course of the 19th century.[27]

After 50 years of Qajar rule, the city still barely had more than 80,000 inhabitants.[26] Up until the 1870s, Tehran consisted of a walled citadel, a roofed bazaar, and the three main neighborhoods of Udlajan, Chale-Meydan, and Sangelaj, where the majority resided.

The first development plan of Tehran in 1855 emphasized traditional spatial structure. The second, under the supervision of Dar ol Fonun in 1878, included new city walls, in the form of a perfect octagon with an area of 19 square kilometers, mimicking the Renaissance cities of Europe.[28] Tehran was 19.79 square kilometers, and had expanded more than fourfold.[29]

Late modern era

Growing awareness of civil rights resulted in the Constitutional Revolution and the first constitution of Iran in 1906. On 2 June 1907, the parliament passed a law on local governance known as the Baladie (municipal law), providing a detailed outline of issues such as the role of councils within the city, the members' qualifications, the election process, and the requirements to be entitled to vote. The then-Qajar monarch Mohammad Ali Shah abolished the constitution and bombarded the parliament with the help of the Russian-controlled Cossack Brigade on 23 June 1908. That was followed by the capture of the city by the revolutionary forces of Ali-Qoli Khan (Sardar Asad II) and Mohammad Vali Khan (Sepahsalar e Tonekaboni) on 13 July 1909. As a result, the monarch was exiled and replaced by his son Ahmad, and the parliament was re-established.

After World War I, the constituent assembly elected Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty as the new monarch, who immediately suspended the Baladie law of 1907, replacing the decentralized and autonomous city councils with centralist approaches to governance and planning.[28]

From the 1920s to the 1930s, under the rule of Reza Shah, the city was essentially rebuilt from scratch. Several old buildings, including parts of the Golestan Palace, Tekye Dowlat, and Tupkhane Square, were replaced with modern buildings influenced by classical Iranian architecture, particularly the buildings of the National Bank, the police headquarters, the telegraph office, and the military academy.

Changes to the urban fabric began with the street-widening act of 1933, which served as a framework for changes in all other cities. The Grand Bazaar was divided in half and many historic buildings were demolished and replaced by wide straight avenues,[30] and the traditional texture of the city was replaced with intersecting cruciform streets that created large roundabouts in major public spaces such as the bazaar.

As an attempt to create a network for easy transportation within the city, the old citadel and city walls were demolished in 1937, replaced by wide streets cutting through the urban fabric. The new city map of Tehran in 1937 was heavily influenced by modernist planning patterns of zoning and gridiron networks.[28]

During World War II, Soviet and British troops entered the city. In 1943, Tehran was the site of the Tehran Conference, attended by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Tupkhane Square in 1911

Tupkhane Square in 1911 Jalili Square (Khaiyam) street in Tehran in 1930

Jalili Square (Khaiyam) street in Tehran in 1930 University of Tehran's Faculty of Law in 1939

University of Tehran's Faculty of Law in 1939 National Bank of Iran, Sabze-Meydan, in the 1940s

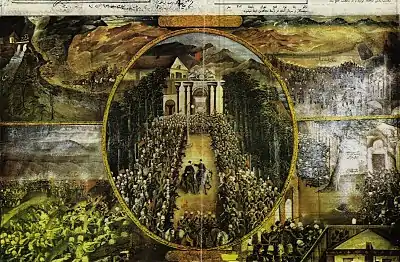

National Bank of Iran, Sabze-Meydan, in the 1940s The Tehran Conference in 1943

The Tehran Conference in 1943 The former Parliament Building in 1956

The former Parliament Building in 1956 Ferdowsi Avenue in 1960

Ferdowsi Avenue in 1960_Blvd-Tehran-1970s.jpg.webp) Keshavarz Boulevard in 1970

Keshavarz Boulevard in 1970 Karimkhan Street in 1977

Karimkhan Street in 1977

The establishment of the planning organization of Iran in 1948 resulted in the first socioeconomic development plan to cover from 1949 to 1955. These plans not only failed to slow the unbalanced growth of Tehran but with the 1962 land reforms that Reza Shah's son and successor Mohammad Reza Shah named the White Revolution, Tehran's chaotic growth was further accentuated.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Tehran developed rapidly under Mohammad Reza Shah. Modern buildings altered the face of Tehran and ambitious projects were planned for the following decades. To resolve the problem of social exclusion, the first comprehensive plan was approved in 1968. The consortium of Iranian architect Abd-ol-Aziz Farmanfarmaian and the American firm of Victor Gruen Associates identified the main problems blighting the city as high-density suburbs, air and water pollution, inefficient infrastructure, unemployment, and rural-urban migration. Eventually, the whole plan was marginalized by the 1979 Revolution and the subsequent Iran–Iraq War.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Tehran's most famous landmark, the Azadi Tower, was built by the order of the Shah in 1971. It was designed by Hossein Amanat, an architect whose design won a competition, combining elements of classical Sassanian architecture with post-classical Iranian architecture. Formerly known as the Shahyad Tower, it was built to commemorate the 2,500th anniversary of the Imperial State of Iran.

During the Iran–Iraq War in 1980 to 1988, Tehran was repeatedly targeted by airstrikes and Scud missile attacks.

The 435-meter-high Milad Tower, one of the proposed development projects of pre-revolutionary Iran,[31] was completed in 2007, and has become a famous landmark of Tehran. Tabiat Bridge a 270-meter pedestrian overpass,[9] designed by award-winning architect Leila Araghian, was completed in 2014.

Geography

Location and subdivisions

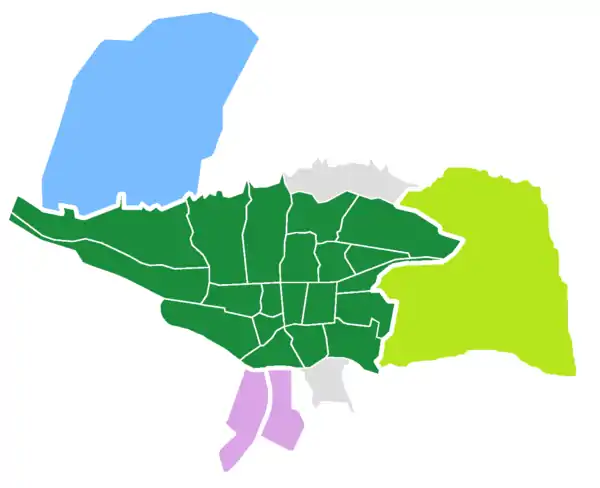

.svg.png.webp)

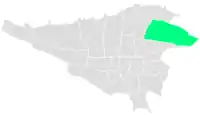

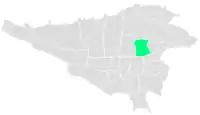

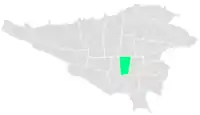

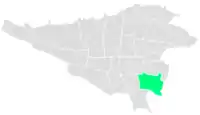

The metropolis of Tehran is divided into 22 municipal districts, each with its own administrative center. Of the 22 municipal districts, 20 are located in Tehran County's Central District, while districts 1 and 20 are respectively located in the counties of Shemiranat and Ray. Although administratively separate, the cities of Ray and Shemiran are often considered part of Greater Tehran.

| Regions and municipal districts of Tehran | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Municipal districts of Tehran | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tehran and Mount Tochal in the winter of 2006

Tehran and Mount Tochal in the winter of 2006 View of Tehran from Tajrish

View of Tehran from Tajrish Elahieh, an upper-class residential and commercial district in northern Tehran

Elahieh, an upper-class residential and commercial district in northern Tehran Ekhtiarieh, an old residential area in northern Tehran

Ekhtiarieh, an old residential area in northern Tehran Tehran from Gheytarieh

Tehran from Gheytarieh Bucharest Street in Abbas Abad, north-central Tehran

Bucharest Street in Abbas Abad, north-central Tehran Resalat Tunnel in Tehran

Resalat Tunnel in Tehran Sattarkhan street in Tehran

Sattarkhan street in Tehran Jordan view

Jordan view Kamranieh alley

Kamranieh alley.jpg.webp) Velenjak north-western Tehran

Velenjak north-western Tehran Pasdaran Street

Pasdaran Street

Northern Tehran is the wealthiest part of the city,[32] consisting of various districts such as Zafaraniyeh, Jordan, Elahiyeh, Pasdaran, Kamranieh, Ajodanieh, Farmanieh, Darrous, Niavaran, Jamaran, Aghdasieh, Mahmoodieh, Velenjak, Qeytarieh, Ozgol and Ekhtiarieh.[33][34] While the center of the city houses government ministries and headquarters, commercial centers are located further north.

Climate

The northern area of Tehran has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa), with a cold semi-arid climate (BSk) elsewhere, with hot dry summers and cool rainy winters. Tehran's climate is largely defined by its geographic location, with the towering Alborz mountains to its north and the country's central desert to the south. It can be generally described as mild in spring and autumn, hot and dry in summer, and cold and wet in winter.

As the city has a large area, with significant differences in elevation among various districts, the weather is often cooler in the hilly north than in the flat southern part of Tehran. For instance, the 17.3 km (10.7 mi) Valiasr Street runs from Tehran's railway station at 1,117 m (3,665 ft) elevation above sea level in the south of the city to Tajrish Square at 1712.6 m (5612.3 ft) elevation above sea level in the north.[35] However, the elevation can even rise up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) at the end of Velenjak in northern Tehran. The sparse texture, the existence of old gardens, orchards, green spaces along the highways and the lack of industrial activities in the north of the city have helped the air in the northern areas to be 2 to 3 degrees Celsius cooler than the southern areas of the city.[36]

The main direction of the prevailing wind in Tehran is northwest to southeast.[37] Other air currents that blow in the area of Tehran are:

- Tochal breeze: With the rapid cooling of the Alborz mountain range at night, a local high-pressure center is formed on Mount Tochal, and this cold current flows down the mountain due to its weight and high pressure; Thus, a gentle breeze blows into the city from the north at night.[36]

- Southern and southeastern regional winds: these winds blow from the desert plains in the hot months of the year.[36]

- Western winds: These winds are among the planetary winds that affect the city of Tehran more or less throughout the year and can be called the prevailing wind.[36]

Air currents have a great effect on Tehran's weather. The prevailing wind blowing from the west causes the west of the city to always be exposed to fresh air; Although this wind brings smoke and pollution from the western industrial areas, its strong wind can take the polluted air out of the city of Tehran.[36]

In most years, winter provides half of Tehran's total annual rainfall. March is the rainiest month of the year and about one-fifth of the annual rainfall occurs in it. Summer is also the least rainy season and September is the driest month of the year in Tehran. The average annual rainfall of the city is sometimes very different in the north and south regions.[36] There are between 205 and 213 days of clear to partly cloudy weather in Tehran.[38]

One of the most intense rains in Tehran happened on 21 April 1962 and this rain lasted for 10 hours. Meteorology also announced that the amount of rainfall on that one day in Tehran was equivalent to six years.[39]

Summer is hot and dry with little rain, but relative humidity is generally low, making the heat tolerable. Average high temperatures are between 31 °C (88 °F) and 38 °C (100 °F) during summer months, and it can sometimes rise up to 40 °C (104 °F) during heat waves. Average low temperatures in summer are between 18 °C (64 °F) and 25 °C (77 °F), and it can occasionally drop to below 14 °C (57 °F) in the mountainous north of the city at night.

Winter is cold and occasionally snowy, with an average of 12.3 snow days annually in central Tehran and more than 23.7 snow days annually in northern Tehran. During the winter months, average high temperatures are between 3 °C (37 °F) and 11 °C (52 °F) and average low temperatures are between −5 °C (23 °F) and 1 °C (34 °F), and it can occasionally drop to below −10 °C (14 °F) during cold waves.

Most of the annual precipitation occurs from late autumn to mid-spring. March is the wettest month with an average precipitation of 39.6 millimetres (1.56 in). The hottest month is July, with a mean minimum temperature of 24 °C (75 °F) and a mean maximum temperature of 36.7 °C (98.1 °F), and the coldest is January, with a mean minimum temperature of −0.4 °C (31.3 °F) and a mean maximum temperature of 7.9 °C (46.2 °F).[40]

The highest recorded temperature was 43 °C (109 °F) on 3 July 1958 and the lowest recorded temperature was −15 °C (5 °F) on 8 January 1969.

| Climate data for Tehran Mehrabad, altitude: 1190.8 m (1951–2020, sun hours 1951-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

37.0 (98.6) |

42.2 (108.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

33.4 (92.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

22.8 (73.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

17.5 (63.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.0 (5.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

2.4 (36.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.3 (1.31) |

33.5 (1.32) |

38.4 (1.51) |

30.9 (1.22) |

14.4 (0.57) |

2.7 (0.11) |

2.5 (0.10) |

1.8 (0.07) |

1.0 (0.04) |

12.5 (0.49) |

27.5 (1.08) |

33.1 (1.30) |

231.6 (9.12) |

| Average precipitation days | 8.5 | 8.2 | 10.2 | 10.1 | 8.4 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 73 |

| Average snowy days | 4.6 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 11.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62 | 55 | 46 | 39 | 32 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 36 | 49 | 61 | 40 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 168.8 | 179.8 | 203.0 | 220.6 | 287.0 | 346.3 | 345.9 | 333.6 | 302.8 | 249.9 | 202.9 | 168.9 | 3,009.5 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Source 1: Iran Meteorological Organization (records[41] (temperatures[42]), (precipitation[43]), (humidity[44]), (days with precipitation[45][46]), (sunshine[47]) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[48] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tehran-Shomal (north of Tehran), altitude: 1549.1 m (1988–2010, temperature normals, extremes, precipitation, and snow days 1988-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.6 (94.3) |

40.4 (104.7) |

41.8 (107.2) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.9 (98.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

19.6 (67.3) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.9 (94.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

17.0 (62.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

15.8 (60.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

10.7 (51.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.0 (8.6) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.6 (2.23) |

64.2 (2.53) |

70.1 (2.76) |

54.9 (2.16) |

25.6 (1.01) |

3.9 (0.15) |

5.0 (0.20) |

3.9 (0.15) |

3.7 (0.15) |

24.5 (0.96) |

53.8 (2.12) |

61.1 (2.41) |

427.3 (16.83) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.3 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 89.1 |

| Average snowy days | 7.3 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 20.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67 | 59 | 53 | 44 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 33 | 44 | 57 | 66 | 46 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 135.8 | 146.4 | 185.1 | 215.0 | 274.6 | 322.8 | 331.8 | 327.5 | 292.6 | 245.5 | 171.5 | 135.8 | 2,784.4 |

| Source 1: [49] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [50] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tehran Geophysic, altitude: 1418.6 m (1991–2010, temperature normals and precipitation 1991-2020, records 1991-2022) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

28.4 (83.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

41.6 (106.9) |

40.1 (104.2) |

37.3 (99.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

32.6 (90.7) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.3 (61.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

17.3 (63.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.7 (10.9) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.4 (1.87) |

38.7 (1.52) |

51.9 (2.04) |

40.5 (1.59) |

17.3 (0.68) |

3.6 (0.14) |

3.2 (0.13) |

2.5 (0.10) |

2.0 (0.08) |

17.2 (0.68) |

36.1 (1.42) |

39.5 (1.56) |

299.9 (11.81) |

| Average precipitation days | 10.0 | 9.1 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 77.1 |

| Average snowy days | 5.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 13.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 157.3 | 172.3 | 198.1 | 213.8 | 279.1 | 342.4 | 345.2 | 346.7 | 308.4 | 257.1 | 180.1 | 146.8 | 2,947.3 |

| Source 1: Iran Meteorological Organization (records[41] (temperatures[42]), (precipitation[51]), (humidity[44]), (days with precipitation[45][46]), (sunshine[47]) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [50] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tehran Chitgar, altitude: 1305.2 m (1996–2005, temperature normals 1996-2022, records 1996-2021) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.6 (90.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

41.1 (106.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

41.1 (106.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

33.4 (92.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

42.0 (107.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

34.1 (93.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

17.6 (63.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.1 (1.50) |

30.1 (1.19) |

48.9 (1.93) |

42.3 (1.67) |

14.3 (0.56) |

1.0 (0.04) |

3.7 (0.15) |

1.0 (0.04) |

1.1 (0.04) |

13.7 (0.54) |

28.9 (1.14) |

46.8 (1.84) |

269.9 (10.64) |

| Average precipitation days | 8.3 | 6.4 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 61.8 |

| Average snowy days | 3.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 8.9 |

| Source 1: [49] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [50] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tehran Imam Khomeini Airport, altitude: 990.2 m (2004–2021, snow days 2004-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.2 (66.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

40.2 (104.4) |

43.5 (110.3) |

45.0 (113.0) |

43.8 (110.8) |

40.4 (104.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

37.1 (98.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

37.9 (100.2) |

33.7 (92.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

11.2 (52.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.2 (−4.4) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24.6 (0.97) |

18.9 (0.74) |

25.6 (1.01) |

25.0 (0.98) |

12.0 (0.47) |

2.6 (0.10) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.7 (0.03) |

1.8 (0.07) |

8.1 (0.32) |

21.6 (0.85) |

19.4 (0.76) |

162 (6.37) |

| Average snowy days | 4.4 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 8.1 |

| Source 1: [49] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [50] | |||||||||||||

In February 2005, heavy snow covered all parts of the city. Snow depth was recorded as 15 cm (6 in) in the southern part of the city and 100 cm (39 in) in the northern part of city. One newspaper reported that it had been the worst weather in 34 years. Ten thousand bulldozers and 13,000 municipal workers were deployed to keep the main roads open.[52][53]

On 5 and 6 January 2008, a wave of heavy snow and low temperatures covered the city in a thick layer of snow and ice, forcing the Council of Ministers to officially declare a state of emergency and close down the capital from 6 January through 7 January.[54]

On 3 February 2014, Tehran received heavy snowfall, specifically in the northern parts of the city, with a depth of 2 metres (6.6 ft). In one week of successive snowfalls, roads were made impassable in some areas, with the temperature ranging from −8 °C (18 °F) to −16 °C (3 °F).[55]

On 3 June 2014, a severe thunderstorm with powerful microbursts created a haboob, engulfing the city in sand and dust and causing five deaths, with more than 57 injured. This event also knocked down numerous trees and power lines. It struck between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m., dropping temperatures from 33 °C (91 °F) to 19 °C (66 °F) within an hour. The dramatic temperature drop was accompanied by wind gusts reaching nearly 118 kilometres per hour (73 mph) .[56]

Environmental issues

A plan to move the capital has been discussed many times in prior years, due mainly to the environmental issues of the region. Tehran is one of the world's most polluted cities and is also located near two major fault lines.

The city suffers from severe air pollution, 80% of it due to cars.[57] The remaining 20% is due to industrial pollution. Other estimates suggest that motorcycles alone account for 30% of air and 50% of noise pollution in Tehran.[58] Tehran is also considered one of the strongest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the Middle East. Enhanced concentration of carbon dioxide over the city (that are likely originated from the anthropogenic urban sources in the city) is easily detectable from satellite observations throughout the year.[59]

In 2010, the government announced that "for security and administrative reasons, the plan to move the capital from Tehran has been finalized."[60] There are plans to relocate 163 state firms and several universities from Tehran to avoid damages from a potential earthquake.[60][61]

The officials are engaged in a battle to reduce air pollution. It has, for instance, encouraged taxis and buses to convert from petrol engines to engines that run on compressed natural gas. Furthermore, the government has set up a "Traffic Zone" covering the city centre during peak traffic hours. Entering and driving inside this zone is only allowed with a special permit.

There have also been plans to raise people's awareness of the hazards of pollution. One method that is being employed is the installation of Pollution Indicator Boards all around the city to monitor the level of particulate matter (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and carbon monoxide (CO).

Demographics

.png.webp)

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1554 | 1,000 | — |

| 1626 | 3,000 | +1.54% |

| 1797 | 15,000 | +0.95% |

| 1807 | 50,000 | +12.79% |

| 1812 | 60,000 | +3.71% |

| 1834 | 80,000 | +1.32% |

| 1867 | 147,256 | +1.87% |

| 1930 | 250,000 | +0.84% |

| 1940 | 540,087 | +8.01% |

| 1956 | 1,560,934 | +6.86% |

| 1966 | 2,719,730 | +5.71% |

| 1976 | 4,530,223 | +5.23% |

| 1986 | 6,058,207 | +2.95% |

| 1991 | 6,497,238 | +1.41% |

| 1996 | 6,758,845 | +0.79% |

| 2006 | 7,711,230 | +1.33% |

| 2011 | 8,244,759 | +1.35% |

| 2016 | 8,737,510 | +1.17% |

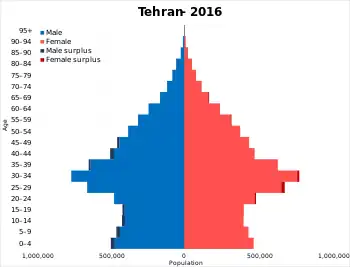

The city of Tehran had a population of 7,711,230 in 2,286,787 households at the time of the 2006 National Census.[63] The following census in 2011 counted 8,154,051 people in 2,624,511 households.[64] The latest census in 2016 showed a population of 8,693,706 people in 2,911,065 households.[65]

With its cosmopolitan atmosphere, Tehran is home to diverse ethnic and linguistic groups from all over the country. The present-day dominant language of Tehran is the Tehrani variety of the Persian language, and the majority of people in Tehran identify themselves as Persians.[11][10] However, before, the native language of the Tehran–Ray region was not Persian, which is linguistically Southwest Iranian and originates in Fars, but a now extinct Northwestern Iranian language.[66]

Iranian Azeris form the second-largest ethnic group of the city, comprising about 10-15% [67][68] of the total population, while ethnic Mazanderanis are the third-largest, comprising about 5% of the total population.[69] Tehran's other ethnic communities include Kurds, Armenians, Georgians, Bakhtyaris, Talysh, Baloch, Assyrians, Arabs, Jews, and Circassians.

According to a 2010 census conducted by the Sociology Department of the University of Tehran, in many districts of Tehran across various socio-economic classes in proportion to population sizes of each district and socio-economic class, 63% of the people were born in Tehran, 98% knew Persian, 75% identified themselves as ethnic Persian, and 13% had some degree of proficiency in a European language.[10]

Tehran saw a drastic change in its ethnic-social composition in the early 1980s. After the political, social, and economic consequences of the 1979 Revolution and the years that followed, a number of Iranian citizens, mostly Tehranis, left Iran. The majority of Iranian emigrations have left for the United States, Germany, Sweden, and Canada.

With the start of the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), the second wave of inhabitants fled the city, especially during the Iraqi air offensives on the capital. With most major powers backing Iraq at the time, economic isolation gave yet more reason for many inhabitants to leave the city (and the country). Having left all they had and have struggled to adapt to a new country and build a life, most of them never came back when the war was over. During the war, Tehran also received a great number of migrants from the west and the southwest of the country bordering Iraq.

The unstable situation and the war in neighbouring Afghanistan and Iraq prompted a rush of refugees into the country who arrived in their millions, with Tehran being a magnet for much seeking work, who subsequently helped the city to recover from war wounds, working for far less pay than local construction workers. Many of these refugees are being repatriated with the assistance of the UNHCR, but there are still sizable groups of Afghan and Iraqi refugees in Tehran who are reluctant to leave, being pessimistic about the situation in their own countries. Afghan refugees are mostly Dari-speaking Tajik and Hazara, speaking a variety of Persian, and Iraqi refugees are mainly Mesopotamian Arabic-speakers who are often of Iranian and Persian ethnic heritage.

Religion

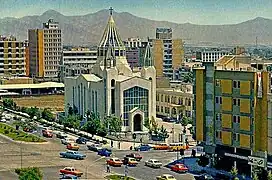

The majority of Tehranis are officially Twelver Shia Muslims, which has also been the state religion since the 16th-century Safavid conversion. Other religious communities in the city include followers of the Sunni and Mystic branches of Islam, various Christian denominations, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and the Baháʼí Faith.

As per a 2003 survey, 60% of Tehranis consider religion to be "very important", 25% "important" and 13% "not important", while 41% of Tehranis identify as "very pious", 41% as "pious" and 16% as "not pious."[70] A 2016 survey found out that, among Tehranis, 53.5% consider religion to be "very important / important", 31.1% to be "rather important", 10.5% to be "not very important" and 4.8% to be "not at all important."[71]

There are many religious centres scattered around the city, from old to newly built centres, including mosques, churches, synagogues, and Zoroastrian fire temples. The city also has a very small third-generation Indian Sikh community with a local gurdwara that was visited by the Indian Prime Minister in 2012.[72]

Tehran's Shah Mosque

Tehran's Shah Mosque Tehran's Greek Orthodox Church of Virgin Mary

Tehran's Greek Orthodox Church of Virgin Mary Saint Mary Armenian Apostolic Church, Tehran

Saint Mary Armenian Apostolic Church, Tehran St. Joseph Assyrian Catholic (Chaldean Catholic) Church, Tehran

St. Joseph Assyrian Catholic (Chaldean Catholic) Church, Tehran Assyrian Church of the East of Mar Sarkis, Tehran

Assyrian Church of the East of Mar Sarkis, Tehran Tehran's Yusef Abad Synagogue

Tehran's Yusef Abad Synagogue Adrian Fire Temple, Tehran

Adrian Fire Temple, Tehran

Economy

Tehran is the economic centre of Iran.[73] About 30% of Iran's public-sector workforce and 45% of its large industrial firms are located in the city, and almost half of these workers are employed by the government.[74] Most of the remainder of workers are factory workers, shopkeepers, laborers, and transport workers.

Few foreign companies operate in Tehran, due to the government's complex international relations. But prior to the 1979 Revolution, many foreign companies were active in Iran.[75] Tehran's present-day modern industries include the manufacturing of automobiles, electronics and electrical equipment, weaponry, textiles, sugar, cement, and chemical products. It is also a leading centre for the sale of carpets and furniture. The oil refining companies of Pars Oil, Speedy, and Behran are based in Tehran.

Tehran relies heavily on private cars, buses, motorcycles, and taxis, and is one of the most car-dependent cities in the world. The Tehran Stock Exchange, which is a full member of the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE) and a founding member of the Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchanges, has been one of the world's best-performing stock exchanges in recent years.[76]

Shopping

Tehran has a wide range of shopping centers, and is home to over 60 modern shopping malls.[77] The city has a number of commercial districts, including those located at Valiasr, Davudie, and Zaferanie. The largest old bazaars of Tehran are the Grand Bazaar and the Bazaar of Tajrish. Iran Mall is the largest mall in the world in area.[78]

Most of the international branded stores and upper-class shops are in the northern and western parts of the city. Tehran's retail business is growing with several newly built malls and shopping centres.[77]

Tiraje Mall in western Tehran

Tiraje Mall in western Tehran Kourosh Mall in Shahid Sattari Expressway

Kourosh Mall in Shahid Sattari Expressway Tehran's Old Grand Bazaar

Tehran's Old Grand Bazaar.jpg.webp) OPAL Shopping Cente

OPAL Shopping Cente

List of modern and most-visited Shopping Malls in Tehran Province:[79]

- Mega Mall

- Bamland Shopping Center

- Palladium Shopping Center

- Sam Center

- Iran Mall

- Kourosh Mall

- Tirajeh Shopping Center

- Modern Elahiyeh Shopping Center

- Donyaye Noor Shopping Centre

- Tandis Shopping Center

- Ava Centre

- Atlas Mall

- Goldis Mall

- OPAL Shopping Center

- Rosha Department Store

- Sivan Center

- Arg Shopping Center

- Nasr Shopping Center

- Galleria Shopping Center

- Charso Mall

- Mirdamad Shopping Center

- Royal Address Complex

- Platin Shopping Center

- Sana Shopping Center

- Sepid Shopping Center Tehran

- Najm Khavar Mianeh

- Parsian Shopping Center

- Artemis Shopping Center

- Heravi Center Shopping Mall

- Tuba shopping center

- Lale Shopping Center

- Andisheh Shopping Center

- Sky Center

- Lotus Mall

- Saba Shopping Mall

- Seven Center Shopping Mall

- Kasa Shopping

- Platin Shopping Center

Tourism

Tehran, as one of the main tourist destinations in Iran, has a wealth of cultural attractions. It is home to royal complexes of Golestan, Saadabad and Niavaran, which were built under the reign of the country's last two monarchies.

There are several historic, artistic, and scientific museums in Tehran, including the

- National Museum

- Malek Museum

- Cinema Museum at Ferdows Garden

- Abgineh Museum

- Museum of the Qasr Prison

- Carpet Museum

- Reverse Glass Painting Museum (vitray art)

- Safir Office Machines Museum

Also the Museum of Contemporary Art, which hosts works of famous artists such as Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol. The Iranian Imperial Crown Jewels, one of the largest jewel collections in the world, are also on display at Tehran's National Jewelry Museum.

A number of cultural and trade exhibitions take place in Tehran, which are mainly operated by the country's International Exhibitions Company. Tehran's annual International Book Fair is known to the international publishing world as one of the most important publishing events in Asia.[80]

Hotel

- Espinas Palace Hotel

- Parsian Azadi Hotel

- Fereshteh Pasargad Hotel

- Laleh International Hotel

- Parsian Enghelab Hotel

- Parsian Esteghlal International Hotel

- Parsian Evin Hotel

- Ibis Hotel

- Espinas International Hotel

- Persian Plaza Hotel

- Hanna Boutique Hotel

- Homa Hotel

- Rexan Hotel

- Tehran Heritage Hostel

- Tehran Grand 1 Hotel

- Iran Cozy Hotel

- Pamchal Hotel

- Amatis Hotel

- Hotel Markazi Iran

- Marlik Hotel

- Ferdowsi Grand Hotel

- Atana Hotel

- Valiasr Hotel

- Taj Mahal Hotel

- Morvarid Hotel

- Hally Hotel

- Howeyzeh hotel

- Atlas Hotel

- Amir Hotel

Espinas Palace Hotel

Espinas Palace Hotel.jpg.webp) Parsian Esteghlal International Hotel

Parsian Esteghlal International Hotel Ferdowsi Grand Hotel

Ferdowsi Grand Hotel Homa Hotel

Homa Hotel Laleh International Hotel

Laleh International Hotel.jpg.webp) Parsian Azadi Hotel

Parsian Azadi Hotel

Infrastructure

Highways and streets

Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the political system changed from constitutional monarchy to Islamic republic. Then the construction of political power in the country needed to change so that new spectrums of political power decision-making centers emerged in Iran. Motives, desires and actions of these new political power decision-making centers in Iran, made them rename streets and public places throughout the country, especially Tehran. For example Shahyad square changed to Azadi square and Pahlavi street changed to Valiasr street.[81]

The metropolis of Tehran is equipped with a large network of highways and interchanges.

A number of streets in Tehran are named after international figures, including:

- Henri Corbin Street, central Tehran

- Simon Bolivar Boulevard, northwestern Tehran

- Edward Browne Street, near the University of Tehran

- Gandhi Street, northern Tehran

- Mohammad Ali Jenah Expressway, western Tehran

- Iqbal Lahori Street, eastern Tehran

- Patrice Lumumba Street, western Tehran

- Nelson Mandela Boulevard, northern Tehran

- Bobby Sands Street, western side of the British Embassy

Cars

According to the head of Tehran Municipality's Environment and Sustainable Development Office, Tehran was designed to have a capacity of about 300,000 cars, but more than five million cars are on the roads.[82] The automotive industry has recently developed, but international sanctions influence the production processes periodically.[83]

According to local media, Tehran has more than 200,000 taxis plying the roads daily,[84] with several types of taxi available in the city. Airport taxis have a higher cost per kilometer as opposed to regular green and yellow taxis in the city.

Buses

Buses have served the city since the 1920s. Tehran's transport system includes conventional buses, trolleybuses, and bus rapid transit (BRT). The city's four major bus stations include the South Terminal, the East Terminal, the West Terminal, and the northcentral Beyhaghi Terminal.

The trolleybus system was opened in 1992, using a fleet of 65 articulated trolleybuses built by Czech Republic's Škoda.[85] This was the first trolleybus system in Iran.[85] In 2005, trolleybuses were operating on five routes, all starting at Imam Hossein Square.[86] Two routes running northeastwards operated almost entirely in a segregated busway located in the middle of the wide carriageway along Damavand Street, stopping only at purpose-built stops located about every 500 metres along the routes, effectively making these routes trolleybus-BRT (but they were not called such). The other three trolleybus routes ran south and operated in mixed traffic. Both route sections were served by limited-stop services and local (making all stops) services.[86] A 3.2-kilometer extension from Shoosh Square to Rah Ahan Square was opened in March 2010.[87] Visitors in 2014 found that the trolleybus system had closed, apparently sometime in 2013.[88] However, it reopened in March 2016, operating on a single 1.8-km route between Meydan-e-Khorasan (Khorasan Square) and Bozorgrah-e-Be'sat.[89][90] Around 30 vehicles had been refurbished and returned to service.[89][90] Extensions were planned.[90]

Tehran's bus rapid transit (BRT) was officially inaugurated in 2008. It has 10 lines with some 215 stations in different areas of the city. As of 2011, the BRT system had a network of 100 kilometres (62 miles), transporting 1.8 million passengers on a daily basis.

Bicycle

Bdood is a dockless bike-sharing company in Iran. Founded in 2017, it is available in the central and northwest regions of the capital city of Tehran. The company has plans to expand across the city in the future.

In the first phase, the application covers the flat areas of Tehran and they would be out of use in poor weather conditions.

Riders can use 29 parking lots for the bikes across Enqelab Avenue, Keshavarz Boulevard, Beheshti Street and Motahhari Avenue in which the bikes are available 24/7 for riders.

Railway and subway

Tehran has a central railway station that connects services round the clock to various cities in the country, along with a Tehran–Europe train line also running.

The feasibility study and conceptual planning of the construction of Tehran's subway system were started in the 1970s. The first two of the eight projected metro lines were opened in 2001.

| Line | Opening[91] | Length | Stations[92] | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2001 | 70 km (43 mi)[93] | 32[93][94] | Metro |

| 2 | 2000 | 26 km (16 mi)[95] | 22[94][95] | Metro |

| 3 | 2012 | 37 km (23 mi)[96] | 24[94][96] | Metro |

| 4 | 2008 | 22 km (14 mi)[97] | 22[97] | Metro |

| 5 | 1999 | 43 km (27 mi)[98] | 11[98][99] | Commuter rail |

| 6 | 2019 | 9 km (5.6 mi)[100] | 3 | Metro |

| 7 | 2017 | 13.5 km (8.4 mi)[101] | 8 | Metro |

| Metro Subtotal: | 177.5 km (110 mi) | 111 | ||

| Total: | 220.5 km (137 mi) | 122 | ||

Airport

Tehran is served by the international airports of Mehrabad and Imam Khomeini. Mehrabad Airport, an old airport in western Tehran that doubles as a military base, is mainly used for domestic and charter flights. Imam Khomeini Airport, located 50 kilometres (31 miles) south of the city, handles the main international flights.

Parks and green spaces

There are over 2,100 parks within the metropolis of Tehran,[102] with one of the oldest being Jamshidie Park, which was first established as a private garden for Qajar prince Jamshid Davallu, and was then dedicated to the last empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi. The total green space within Tehran stretches over 12,600 hectares, covering over 20 percent of the city's area. The Parks and Green Spaces Organization of Tehran was established in 1960, and is responsible for the protection of the urban nature present in the city.[103]

Tehran's Birds Garden is the largest bird park in Iran. There is also a zoo located on the Tehran–Karaj Expressway, housing over 290 species within an area of about five hectares.[104]

In 2009, the Ab-o-Atash Park ("Water and Fire park") was founded. Its main features are an open water fountain area for cooling in the hot climate, fire towers, and an amphitheatre.[105]

Energy

Water

Greater Tehran with its population of more than 13 million is supplied by surface water from the Lar dam on the Lar River in the Northeast of the city, the Latyan dam on the Jajrood River in the North, the Karaj River in the Northwest, as well as by groundwater in the vicinity of the city.

Solar Energy

Solar panels have been installed in Tehran's Pardisan Park for green electricity production, said Masoumeh Ebtekar, head of the Department of Environment.

According to the national energy roadmap, the government plans to promote green technology to increase the nominal capacity of power plants from 74 gigawatts to over 120 gigawatts by the end of 2025.[106]

Education

.jpg.webp)

Tehran is the largest and most important educational center in Iran. There are a total of nearly 50 major colleges and universities in Greater Tehran.

Since the establishment of Dar ol Fonun by the order of Amir Kabir in the mid-19th century, Tehran has amassed a large number of institutions of higher education. Some of these institutions have played crucial roles in the unfolding of Iranian political events. Samuel M. Jordan, whom Jordan Avenue in Tehran was named after, was one of the founding pioneers of the American College of Tehran, which was one of the first modern high schools in the Middle East.

Among major educational institutions located in Tehran, Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic), University of Tehran, Sharif University of Technology, and Tehran University of Medical Sciences are the most prestigious. Other major universities located in Tehran include Tehran University of Art, Allameh Tabatabaei University, K. N. Toosi University of Technology, Shahid Beheshti University (Melli University), Kharazmi University, Iran University of Science and Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology, Iran's Polymer and Petrochemical Institute, Shahed University, and Tarbiat Modarres University. Sharif University of Technology, Amirkabir University of Technology, Iran University of Science and Technology and K. N. Toosi University of Technology also located in Tehran are nationally well known for taking in the top undergraduate Engineering and Science students; and internationally recognized for training competent under graduate students. It has probably the highest percentage of graduates who seek higher education abroad.

Tehran is also home to Iran's largest military academy, and several religious schools and seminaries.

Culture

Architecture

The oldest surviving architectural monuments of Tehran are from the Qajar and Pahlavi eras. In Greater Tehran, monuments dating back to the Seljuk era remain as well; notably the Toqrol Tower in Ray. Rashkan Castle, dating back to the ancient Parthian Empire, of which some artifacts are housed at the National Museum;[107] and the Bahram fire temple, which remains since the Sassanian Empire.

Tehran only had a small population until the late 18th century but began to take a more considerable role in Iranian society after it was chosen as the capital city. Despite the regular occurrence of earthquakes during the Qajar period and after, some historic buildings remain from that era.[108]

Tehran is Iran's primate city, and is considered to have the most modernized infrastructure in the country. However, the gentrification of old neighbourhoods and the demolition of buildings of cultural significance have caused concerns.[109]

A view of the building of the City Theater of Tehran

A view of the building of the City Theater of Tehran

Police House,

Police House,

the National Garden Cossack House,

Cossack House,

the National Garden

Previously a low-rise city due to seismic activity in the region, modern high-rise developments in Tehran have been built in recent decades in order to service its growing population. There have been no major quakes in Tehran since 1830.[110]

Tehran International Tower is the tallest skyscraper in Iran. It is 54-stories tall and located in the northern district of Yusef Abad.

The Azadi Tower, a memorial built under the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty, has long been the most famous symbol of Tehran. Originally constructed in commemoration of the 2,500th year of the foundation of the Imperial State of Iran, it combines elements of the architecture of the Achaemenid and Sassanid eras with post-classical Iranian architecture. The Milad Tower, which is the sixth tallest tower[111] and the 24th-tallest freestanding structure in the world,[112] is the city's other famous landmark tower. Leila Araghian's Tabiat Bridge, the largest pedestrian overpass in Tehran, was completed in 2014 and is also considered a landmark.[9]

Theater

Under the reign of the Qajars, Tehran was home to the royal theatre of Tekye Dowlat, located to the southeast of the Golestan Palace, in which traditional and religious performances were observed. It was eventually demolished and replaced with a bank building in 1947, following the reforms during the reign of Reza Shah.

Before the 1979 Revolution, the Iranian national stage had become the most famous performing scene for known international artists and troupes in the Middle East,[113] with the Roudaki Hall of Tehran constructed to function as the national stage for opera and ballet. The hall was inaugurated in October 1967 and named after prominent Persian poet Rudaki. It is home to the Tehran Symphony Orchestra, the Tehran Opera Orchestra, and the Iranian National Ballet Company.

The City Theater of Tehran, one of Iran's biggest theatre complexes, which contains several performance halls, was opened in 1972. It was built at the initiative and presidency of empress Farah Pahlavi, and was designed by architect Ali Sardar Afkhami, constructed within five years.

The annual events of Fajr Theater Festival and Tehran Puppet Theater Festival take place in Tehran.

Cinema

The first movie theater in Tehran was established by Mirza Ebrahim Khan in 1904.[114] Until the early 1930s, there were 15 theaters in Tehran Province and 11 in other provinces.[115]

In present-day Tehran, most of the movie theatres are located downtown. The complexes of Kourosh Cinema, Mellat Gallery and Cineplex, Azadi Cinema, and Cinema Farhang are among the most popular cinema complexes in Tehran.

Several film festivals are held in Tehran, including Fajr Film Festival, Children and Youth Film Festival, House of Cinema Festival, Mobile Film and Photo Festival, Nahal Festival, Roshd Film Festival, Tehran Animation Festival, Tehran Short Film Festival, and Urban Film Festival.

Concerts

There are a variety of concert halls in Tehran. An organization like the Roudaki Culture and Art Foundation has five different venues where more than 500 concerts take place this year. Vahdat Hall, Roudaki Hall, Ferdowsi Hall, Hafez Hall and Azadi Theater are the top five venues in Tehran, where classical, pop, traditional, rock or solo concerts take place.[116]

Sports

Football and volleyball are the city's most popular sports, while wrestling, basketball, and futsal are also major parts of the city's sporting culture.

12 ski resorts operate in Iran, the most famous being Tochal, Dizin, and Shemshak, all within one to three hours from the city of Tehran.

Tochal's resort is the world's fifth-highest ski resort at over 3,730 meters (12,240 feet) above sea level at its highest point. It is also the world's nearest ski resort to a capital city. The resort was opened in 1976, shortly before the 1979 Revolution. It is equipped with an 8-kilometre-long (5 mi) gondola lift that covers a huge vertical distance.[117] There are two parallel chair ski lifts in Tochal that reach 3,900 meters (12,800 feet) high near Tochal's peak (at 4,000 m/13,000 ft), rising higher than the gondola's seventh station, which is higher than any of the European ski resorts. From the Tochal peak, there are views of the Alborz range, including the 5,610-metre-high (18,406 ft) Mount Damavand, a dormant volcano.

Tehran is the site of the national stadium of Azadi, the biggest stadium by capacity in West Asia, where many of the top matches of Iran's Premier League are held. The stadium is a part of the Azadi Sport Complex, which was originally built to host the 7th Asian Games in September 1974. This was the first time the Asian Games were hosted in West Asia. Tehran played host to 3,010 athletes from 25 countries/NOCs, which was at the time the highest number of participants since the inception of the Games.[118] That followed hosting the 6th AFC Asian Cup in June 1976, and then the first West Asian Games in November 1997. The success of the games led to the creation of the West Asian Games Federation (WAGF), and the intention of hosting the games every two years.[119] The city had also hosted the final of the 1968 AFC Asian Cup. Several FIVB Volleyball World League courses have also been hosted in Tehran.

Food

There are many restaurants and cafes in Tehran, both modern and classic, serving both Iranian and cosmopolitan cuisine. Pizzerias, sandwich bars, and kebab shops make up the majority of food shops in Tehran.[120]

A restaurant in Darband

A restaurant in Darband A pizzeria in Kamyab Street, Tehran

A pizzeria in Kamyab Street, Tehran A Japanese restaurant in Tehran

A Japanese restaurant in Tehran Shemroon Cafe, in Tehran's Iranian Art Museum

Shemroon Cafe, in Tehran's Iranian Art Museum 30 Tir food street

30 Tir food street

Graffiti

Many styles of graffiti are seen in Tehran. Some are political and revolutionary slogans painted by governmental organizations,[121] and some are works of art by ordinary citizens, representing their views on both social and political issues. However, unsanctioned street art is forbidden in Iran,[121] and such works are usually short-lived.

During the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, many graffiti works were created by people supporting the Green Movement. They were removed from the walls by the paramilitary Basij forces.[122]

In recent years, Tehran Municipality has been using graffiti in order to beautify the city. Several graffiti festivals have also taken place in Tehran, including the one organized by the Tehran University of Art in October 2014.[123]

Twin towns – sister cities

Ankara, Turkey

Ankara, Turkey Baghdad, Iraq

Baghdad, Iraq Brasília, Brazil

Brasília, Brazil Budapest, Hungary

Budapest, Hungary Dushanbe, Tajikistan

Dushanbe, Tajikistan Havana, Cuba

Havana, Cuba Khartoum, Sudan

Khartoum, Sudan London, England, United Kingdom[125]

London, England, United Kingdom[125] Los Angeles, United States

Los Angeles, United States Manila, Philippines

Manila, Philippines Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia Pretoria, South Africa

Pretoria, South Africa Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina[126]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina[126] Tbilisi, Georgia

Tbilisi, Georgia Yerevan, Armenia

Yerevan, Armenia

Panoramic views

See also

References

- "City of Tehran Statisticalyearbook" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Tehran, Environment & Geography Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine. tehran.ir.

- Urban population: Data for Tehran County. ~97.5% of county population live in Tehran city

Metro population: Estimate on base of census data, includes central part of Tehran province and Karaj County and Fardis from Alborz province - "Population of Tehran". Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Major Agglomerations of the World - Population Statistics and Maps". citypopulation.de. 13 September 2018.

- SI ee List of metropolitan areas in Asia.

- Erdösy, George. (1995). The Indo-Aryans of ancient South Asia: Language, material culture and ethnicity. Walter de Gruyter. p. 165.

Possible western place names are the following: Raya-, which is also the ancient name of Median Raga in the Achaemenid inscriptions (Darius, Bisotun 2.13: a land in Media called Raga) and modern Rey south of Tehran

- "Tehran (Iran) : Introduction – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- "Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge / Diba Tensile Architecture". ArchDaily. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "چنددرصد تهرانیها در تهران به دنیا آمدهاند؟". tabnak.ir (in Persian). 3 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal; McDonald, Peter; Hosseini-Chavoshi, Meimanat. (30 September 2009). "Region of Residence". The Fertility Transition in Iran: Revolution and Reproduction. Springer. pp. 100–101.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schuppe, Mareike. (2008). Coping with Growth in Tehran: Strategies of Development Regulation. GRIN Verlag. p. 13.

Besides Persian, there are Azari, Armenian, and Jewish communities in Tehran. The vast majority of Tehran's residents are Persian-speaking (98.3%).

- Barbaglia, Pamela. (29 March 2016). "Iranian expats hard to woo as Western firms seek a foothold in Iran". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Erenhouse, Ryan. (22 September 2016). "Bangkok Takes Title in 2016 Mastercard Global Destinations Cities Index". MasterCard's newsroom. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- "Citizens of Capital Mark Tehran Day on October 6". 6 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Yahya, Zoka (1978). Karvand of Kasravi. Tehran: Franklin. pp. 273–283.

- Behrooz, Samira; Karampour, Katayoun (15 November 2008). "A Research on Adaptation of Historic Urban Landscapes". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- "آشنایی با شهر تهران". shahrmajazi.com. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- "Tehran | History, Population, & Tourism | Britannica".

- "Tehrān - History".

- Minorsky, Vladimir; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. "Al-Rayy". Encyclopaedia of Islam: New Edition. Vol. 8. pp. 471–473.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta; Stewart, Sarah. (2005). Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B. Tauris. p. 37.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - A. Tafazolli, "In Iranian Mythology" in Encyclopædia Iranica

- (Bulddan, Yackubl, 276)

- Houtum-Schindler, Albert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–507: final para.

- Amanat, Abbas (1997). Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520083219. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2 December 2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. pp. 728–730. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Vahdat Za, Vahid. (2011). "Spatial Discrimination in Tehran's Modern Urban Planning 1906–1979". Journal of Planning History vol. 12 no. 1 49–62. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Shirazian, Reza, Atlas-i Tehran-i Qadim, Dastan Publishing House: Tehran, 2015, P. 11

- Chaichian, Mohammad (2009). Town and Country in the Middle East: Iran and Egypt in the Transition to Globalization. New York: Lexington Books. pp. 95–116. ISBN 978-0-7391-2677-6.

- Vanstiphout, Wouter. "The Saddest City in the World". The New Town. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Iran Lightens Up On Western Ways". Chicago Tribune. 9 May 1993. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Buzbee, Sally. "Tehran: Split Between Liberal, Hard-Line" Archived 2017-08-06 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press via The Washington Post. Thursday 4 October 2007.

- Hundley, Tom. "Pro-reform Khatami appears victorious after 30 million Iranians cast votes". Chicago Tribune. 8 June 2001.

- Tools, Free Map. "Elevation Finder". Freemaptools.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "Tehran Geography" (in Persian). Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- lake (in Persian) Archived 9 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. hamshahrionline.ir

- Climate and air pollution of Tehran (in Persian) . atlas.tehran.ir

- "Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies" (in Persian). Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Climate of Tehran". Irantour.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

-

- "Highest record temperature in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Highest Record temperatures in Tehran by Month 2011–2020". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- "Lowest record temperature in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Lowest record temperatures in Tehran by Month 2011–2020". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

-

- "Average Maximum temperature in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Average Maximum temperatures in Tehran by Month 2011–2020". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- "Average Mean Daily temperature in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Average Minimum temperature in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Average Minimum temperatures in Tehran by Month 2011–2020". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- "Monthly Total Precipitation in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "Average relative humidity in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization.

- "No. Of days with precipitation in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization.

- "No. Of days with snow in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization.

- "Monthly total sunshine hours in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization.

- "Tehran, Iran - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast".

- I.R. OF IRAN SHAHREKORD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION (IN PERSIAN) Archived 2017-08-29 at the Wayback Machine. 1988–2020

- I.R. OF IRAN METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION (IN PERSIAN) Archived 29 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine. 1988–2020

- "Monthly Total Precipitation in Tehran by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- Harrison, Frances (19 February 2005). "Iran gripped by wintry weather". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Heavy Snowfall in Tehran" (in Persian). Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Heavy Snowfall in Tehran (in Persian). irna.com

- "Rare snow blankets Iran's capital Tehran". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Deadly Dust Storm Engulfs Iran's Capital". AccuWeather.com. 3 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Car exhaust fumes blamed for over 80% of air pollution in Tehran". Payvand.com. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Motorcycles Account for 30% of Air Pollution in Tehran". Payvand.com. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- Labzovskii, Lev (2 August 2019). "Working towards confident spaceborne monitoring of carbon emissions from cities using Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2". Remote Sensing of Environment. 233 (2019) 11359. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "For Security and Administrative [sic] Reasons: Plan to Move Capital From Tehran Finalized". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Iran Moots Shifting Capital from Tehran". Payvand.com. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "یک و نیم میلیون مازندرانی پایتخت نشین شدند" (in Persian). IRNA. 3 April 2016.

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 23. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011)" (Excel). Iran Data Portal (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 23. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 23. Archived from the original (Excel) on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Windfuhr, Gernot L. (1991). "Central Dialects". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 5. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 242–252. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Iran-Azeris". Library of Congress Country Studies. December 1987. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "Country Study Guide-Azerbaijanis". STRATEGIC INFORMATION AND DEVELOPMENTS-USA. 2005. ISBN 9780739714768. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "یک و نیم میلیون مازندرانی پایتخت نشین شدند" (in Persian). IRNA. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.