Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope (Afrikaans: Kaap die Goeie Hoop [ˌkɑːp di ˌχujə ˈɦuəp])[lower-alpha 1] is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, based on the misbelief that the Cape was the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian oceans. In fact, the southernmost point of Africa is Cape Agulhas about 150 kilometres (90 mi) to the east-southeast.[1] The currents of the two oceans meet at the point where the warm-water Agulhas current meets the cold-water Benguela current and turns back on itself. That oceanic meeting point fluctuates between Cape Agulhas and Cape Point (about 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) east of the Cape of Good Hope).

When following the western side of the African coastline from the equator, however, the Cape of Good Hope marks the point where a ship begins to travel more eastward than southward. Thus, the first modern rounding of the cape in 1487 by Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias was a milestone in the attempts by the Portuguese to establish direct trade relations with the Far East (although Herodotus mentioned a claim that the Phoenicians had done so far earlier).[2] Dias called the cape Cabo das Tormentas ('Cape of Storms'; Dutch: Stormkaap), which was the original name of the cape.[3]

As one of the great capes of the South Atlantic Ocean, it has long been of special significance to sailors, many of whom refer to it simply as "the Cape".[4] It is a waypoint on the Cape Route and the clipper route followed by clipper ships to the Far East and Australia, and still followed by several offshore yacht races.

The term Cape of Good Hope is also used in three other ways:

- It is a section of the Table Mountain National Park, within which the cape of the same name, as well as Cape Point, falls. Prior to its incorporation into the national park, this section constituted the Cape Point Nature Reserve.[5]

- It was the name of the early Cape Colony established by the Dutch East Indies Company in 1652, on the Cape Peninsula.

- Just before the Union of South Africa was formed, the term referred to the entire region that in 1910 was to become the Cape of Good Hope Province (usually shortened to the Cape Province).

History

Eudoxus of Cyzicus (/ˈjuːdəksəs/; Greek: Εὔδοξος, Eúdoxos; fl. c. 130 BC) was a Greek navigator for Ptolemy VIII, king of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, who found the wreck of a ship in the Indian Ocean that appeared to have come from Gades (today's Cádiz in Spain), rounding the Cape.

When Eudoxus was returning from his second voyage to India, the wind forced him south of the Gulf of Aden and down the coast of Africa for some distance. Somewhere along the coast of East Africa, he found the remains of the ship. Due to its appearance and the story told by the natives, Eudoxus concluded that the ship was from Gades and had sailed anti-clockwise around Africa, passing the Cape and entering the Indian Ocean. This inspired him to repeat the voyage and attempt a circumnavigation of the continent. Organising the expedition on his own account he set sail from Gades and began to work down the African coast. The difficulties were too great, however, and he was obliged to return to Europe.[6]

After this failure he again set out to circumnavigate Africa. His eventual fate is unknown. Although some, such as Pliny, claimed that Eudoxus did achieve his goal, the most probable conclusion is that he perished on the journey.[7]

In the 1450 Fra Mauro map, the Indian Ocean is depicted as connected to the Atlantic. Fra Mauro puts the following inscription by the southern tip of Africa, which he names the "Cape of Diab", describing the exploration by a ship from the East around 1420:[8][9]

Around 1420 a ship, or junk, from India crossed the Sea of India towards the Island of Men and the Island of Women, off Cape Diab, between the Green Islands and the shadows. It sailed for 40 days in a south-westerly direction without ever finding anything other than wind and water. According to these people themselves, the ship went some 2,000 miles ahead until — once favourable conditions came to an end — it turned round and sailed back to Cape Diab in 70 days.

The ships called junks (lit. "Zonchi") that navigate these seas carry four masts or more, some of which can be raised or lowered, and have 40 to 60 cabins for the merchants and only one tiller. They can navigate without a compass, because they have an astrologer, who stands on the side and, with an astrolabe in hand, gives orders to the navigator.

—Text from the Fra Mauro map, 09-P25

Fra Mauro explained that he obtained the information from "a trustworthy source", who traveled with the expedition, possibly the Venetian explorer Niccolò da Conti who happened to be in Calicut, India at the time the expedition left:

What is more, I have spoken with a person worthy of trust, who says that he sailed in an Indian ship caught in the fury of a tempest for 40 days out in the Sea of India, beyond the Cape of Soffala and the Green Islands towards west-southwest; and according to the astrologers who act as their guides, they had advanced almost 2,000 miles. Thus one can believe and confirm what is said by both these and those, and that they had therefore sailed 4,000 miles.

Fra Mauro also comments that the account of the expedition, together with the relation by Strabo of the travels of Eudoxus of Cyzicus from Arabia to Gibraltar through the southern Ocean in Antiquity, led him to believe that the Indian Ocean was not a closed sea and that Africa could be circumnavigated by her southern end (Text from Fra Mauro map, 11, G2). This knowledge, together with the map depiction of the African continent, probably encouraged the Portuguese to intensify their effort to round the tip of Africa.

In 1511, after Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, the Portuguese recovered a chart from a Javanese maritime pilot, which, according to Albuquerque, already included the Cape of Good Hope. Regarding the chart Albuquerque said:[10][11]: 98–99

"...a large map of a Javanese pilot, containing the Cape of Good Hope, Portugal and the land of Brazil, the Red Sea and the Sea of Persia, the Clove Islands, the navigation of the Chinese and the Gores, with their rhumbs and direct routes followed by the ships, and the hinterland, and how the kingdoms border on each other. It seems to me, Sir, that this was the best thing I have ever seen, and Your Highness will be very pleased to see it; it had the names in Javanese writing, but I had with me a Javanese who could read and write. I send this piece to Your Highness, which Francisco Rodrigues traced from the other, in which Your Highness can truly see where the Chinese and Gores come from, and the course your ships must take to the Clove Islands, and where the gold mines lie, and the islands of Java and Banda, of nutmeg and mace, and the land of the King of Siam, and also the end of the land of the navigation of the Chinese, the direction it takes, and how they do not navigate farther."

— Letter of Albuquerque to King Manuel I of Portugal, 1 April 1512.

European exploration

In the Early Modern Era, the first European to reach the cape was the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias on 12 March 1488, who named it the "Cape of Storms" (Cabo das Tormentas). It was later renamed by John II of Portugal as "Cape of Good Hope" (Cabo da Boa Esperança) because of the great optimism engendered by the opening of a sea route to India and the East.

The Khoikhoi people lived in the cape area when the Dutch first settled there in 1652. The Khoikhoi had arrived in this area about fifteen hundred years before.[12] The Dutch called them Hottentots, a term that has now come to be regarded as pejorative.

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company's administrator Jan van Riebeeck established a resupply camp for the Dutch East India Company some 50 km north of the cape in Table Bay on 6 April 1652, and this eventually developed into Cape Town. Supplies of fresh food were vital on the long journey around Africa and Cape Town became known as "The Tavern of the Seas".

On 31 December 1687 a community of Huguenots (French Protestants) arrived at the Cape of Good Hope from the Netherlands. They had fled from France due to religious persecution and gone to the Netherlands, before making the journey to the Cape Colony. Members of this group included Pierre Joubert, who came from La Motte-d'Aigues, as well as Jean Roy. The Dutch East India Company needed skilled farmers at the Cape of Good Hope and the Dutch government saw opportunities to settle Huguenots at the Cape. The colony gradually grew over the next 150 years until it extended hundreds of kilometres to the north and north-east.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Dutch Republic was occupied by the French in 1795. The Cape Colony then became a French vassal and enemy of the British, who were at war with France. British troops invaded and occupied the Cape Colony that same year. The British relinquished control of the territory in 1803, under the peace of Amiens, but reoccupied the Colony on 19 January 1806 following the Battle of Blaauwberg. The Dutch formally ceded the territory to the British in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814. It would remain a separate British colony until its incorporation into the Union of South Africa in 1910.

The Portuguese government erected two navigational beacons, Dias Cross and da Gama Cross, to commemorate Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama, who were the first modern European explorers to reach the cape. When lined up, these crosses point to Whittle Rock, a large, permanently submerged shipping hazard in False Bay. Two other beacons in Simon's Town provide the intersection.

Contemporary

The Cape of Good Hope saw an increase of ship activity after the 2021 Suez canal obstruction, with ships needing a different route from the Indian Ocean.[13][14][15]

Geography

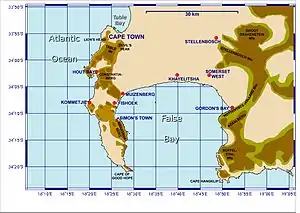

The Cape of Good Hope is at the southern tip of the Cape Peninsula, about 2.3 kilometres (1.4 mi) west and a little south of Cape Point on the south-east corner. Cape Town is about 50 kilometres to the north of the Cape, in Table Bay at the north end of the peninsula. The peninsula forms the western boundary of False Bay. Geologically, the rocks found at the two capes, and indeed over much of the peninsula, are part of the Cape Supergroup, and are formed of the same type of sandstones as Table Mountain itself. Both the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Point offer spectacular scenery; the whole of the southernmost portion of the Cape Peninsula is a wild, rugged, scenic and generally unspoiled national park.

The term "the Cape" has also been used in a wider sense, to indicate the area of the European colony centred on Cape Town, and the later South African province. Since 1994, it has been broken up into three smaller provinces: the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Northern Cape; parts of the province were also absorbed into the North West.

Fauna

With its diverse habitat, ranging from rocky mountain tops to beaches and open sea, the Cape of Good Hope is home to at least 250 species of birds including one of the two mainland colonies of African penguins. "Bush birds" tend to be rather scarce because of the coarse, scrubby nature of fynbos vegetation. When flowering, however, proteas and ericas attract sunbirds, sugarbirds, and other species in search of nectar. For most of the year, there are more small birds in coastal thicket than in fynbos. The Cape of Good Hope section of Table Mountain National Park is home to several species of antelope. Bontebok and eland are easily seen, and red hartebeest can be seen in the grazing lawns in Smitswinkel Flats. Grey rhebok are less commonly seen and are scarce, but may be observed along the beach hills at Olifantsbos. Most visitors are unlikely to ever see either Cape grysbok or klipspringer. The Cape of Good Hope section is home to four Cape mountain zebra. They might be seen by the attentive or lucky visitor, usually in Smitswinkel Flats. There are a wealth of small animals such as lizards, snakes, tortoises and insects. Small mammals include rock hyrax, four-striped grass mouse, water mongoose, Cape clawless otter and fallow deer. The area offers excellent vantage points for whale watching. The southern right whale is the species most likely to be seen in False Bay between June and November. Other species are the humpback whale and Bryde's whale. Seals, dusky dolphins and orcas have also been seen. The strategic position of the Cape of Good Hope between two major ocean currents, ensures a rich diversity of marine life. There is a difference between the sea life west of Cape Point and that to the east due to the markedly differing sea temperatures. The South African Marine Living Resources Act is strictly enforced throughout the Table Mountain National Park, and especially in marine protected areas. Disturbance or removal of any marine organisms is strictly prohibited between Schusters Bay and Hoek van Bobbejaan, but is allowed in other areas during season and with relevant permits.

Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) are the mammals most intimately associated with the Cape of Good Hope. Baboons inside the Cape of Good Hope section of the park are a major tourist attraction. There are 11 troops consisting of about 375 individuals throughout the entire Cape Peninsula. Six of these 11 troops either live entirely within the Cape of Good Hope section of the park, or use the section as part of their range. The Cape Point, Kanonkop, Klein Olifantsbos, and Buffels Bay troops live entirely inside the Cape of Good Hope section of the Park. The Groot Olifantsbos and Plateau Road troops range into the park. Chacma baboons are widely distributed across southern Africa and are classified as ″least concern" in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. However, the South African Parks Department states in its publication Mountains in the Sea that the baboon population on the Cape is "critically endangered." This is due to habitat loss, genetic isolation, and conflicts with humans. Cape baboons have been eliminated from the majority of their range across the Cape Peninsula, and the Cape of Good Hope section of Table Mountain National Park provides a sanctuary for the troops that live within its boundaries. It provides relative safety from nearby towns, where people have killed many baboons after the baboons raid their houses looking for food. Baboons are also frequently injured or killed outside of the park by cars and by electrocution on power lines. Inside the park, some management policies such as allowing barbecues and picnics in the baboon home ranges cause detriment to the troops, as they become embroiled in conflicts with guests to the park. At the Cape in particular, the baboon is known for eating shellfish and other marine invertebrates.[16]

In 1842, Charles Hamilton Smith had described a black-maned lion from the Cape under the scientific name Felis (Leo) melanochaita.[17] No longer seen as a subspecies of its own,[18] the Cape lion as a population is now extinct in the wilderness,[19] though descendants could exist in captivity.[20][21][22]

Flora

The Cape of Good Hope is an integral part of the Cape Floristic Kingdom, the smallest but richest of the world's six floral kingdoms. This comprises a treasure trove of 1100 species of indigenous plants, of which a number are endemic (occur naturally nowhere else on earth). The main type of fynbos ("fine bush") vegetation at the Cape of Good Hope is Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos, an endangered vegetation type that is endemic to the Cape Peninsula. Coastal Hangklip Sand Fynbos grows on low-lying alkaline sands and, right by the sea, small patches of Cape Flats Dune Strandveld can be found.[23][24]

Characteristic fynbos plants include proteas, ericas (heath), and restios (reeds). Some of the most striking and well-known members belong to the Proteacae family, of which up to 24 species occur. These include king protea, sugarbush, tree pincushion and golden cone bush (Leucadendron laureolum).

Many popular horticultural plants like pelargoniums, freesias, daisies, lilies and irises also have their origins in fynbos.

Legends

- The Cape of Good Hope is the legendary home of the Flying Dutchman. According to the legend, crewed by tormented and damned ghostly sailors, it is doomed forever to beat its way through the adjacent waters without ever succeeding in rounding the headland.

- Adamastor is a Greek-type mythological character invented by the Portuguese poet Luís de Camões in his epic poem Os Lusíadas (first printed in 1572), as a symbol of the forces of nature Portuguese navigators had to overcome during their discoveries and more specifically of the dangers they faced when trying to round the Cape of Storms.

See also

- Cape Horn – Headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago located in Chile, its South American counterpart

- Western Cape – Province of South Africa on the south-western coast

- History of Cape Colony – British colony from 1806 to 1910

- Simon's Town – Seaside town in the Western Cape, South Africa

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Cape of Good Hope

Notes

- Dutch: Kaap de Goede Hoop [ˌkaːb də ˌɣudə ˈɦoːp] ⓘ; Kaap in isolation: [kaːp] ⓘ Portuguese: Cabo da Boa Esperança [ˈkaβu ðɐ ˈβoɐ ɨʃpɨˈɾɐ̃sɐ]

References

- "Cape of Good Hope, South Africa - 360° Aerial Panoramas". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- The first circumnavigation of Africa Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine. livius.org

- Sarah Mytton Maury (1848). Englishwoman In America. p. 33.

- Along the Clipper Way, Francis Chichester; page 78. Hodder & Stoughton, 1966. ISBN 978-0-340-00191-2

- "Map of the Park, showing the Cape of Good Hope section (retrieved 27 March 2010)". Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Tozer, Henry F. (1997). History of Ancient Geography. Biblo & Tannen. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-8196-0138-4 – via Google Books.

- Tozer, Henry F. (1997). History of Ancient Geography. Biblo & Tannen. pp. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-8196-0138-4 – via Google Books.

- Marco Polo, p. 409

- Needham 1971, p. 501

- Carta IX, 1 April 1512. In Pato, Raymundo Antonio de Bulhão (1884). Cartas de Affonso de Albuquerque, Seguidas de Documentos que as Elucidam tomo I (pp. 29–65). Lisboa: Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencas. p. 64.

- Olshin, Benjamin B. (1996). "A sixteenth century Portuguese report concerning an early Javanese world map". História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 2 (3): 97–104. doi:10.1590/s0104-59701996000400005. ISSN 0104-5970. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Ehret, Christopher (2001). An African Classical Age. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8139-2057-3.

- Farrer, Martin; Safi, Michael (26 March 2021). "Suez canal: Japanese owner of stricken ship talks of plan to refloat it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- El Wardany, Salma; Magdy, Mirette (27 March 2001). "Ships Divert From Canal; More Tugs Coming: Suez Update". MSN. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- "Container ships turn to Cape of Good Hope as Suez issues continue: cFlow". Bunker World. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- Davidge, C. (1978). "Ecology of baboons (Papio ursinus) at Cape Point". Zoologica Africana. 13 (2): 329–350. doi:10.1080/00445096.1978.11447633.

- Smith, C.H. (1842). "Black maned lion Leo melanochaita". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 177.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11). ISSN 1027-2992. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-17. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- Yamaguchi, N. (2000). "The Barbary lion and the Cape lion: their phylogenetic places and conservation" (PDF). African Lion Working Group News. Vol. 1. pp. 9–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- "'Extinct' lions (Cape lion) surface in Siberia". The BBC. 2000. Archived from the original on 2017-08-24. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- "Лев". Sibzoo.narod.ru. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "South Africa: Lion Cubs Thought to Be Cape Lions". AP Archive, The Associated Press. 2000. Archived from the original on 2019-08-18. Retrieved 2019-08-18. (with 2-minute video of cubs at zoo with John Spence, 3 sound-bites, and 15 photos)

- "Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos. Cape Town Biodiversity Factsheets" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-01.

- "Cape Flats Dune Strandveld. Cape Town Biodiversity Factsheets" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-17.

Bibliography

- Marco Polo (1875), Yule, Henry (ed.), The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian: Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, John Murray

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilisation in China

%252C_cabo_de_Buena_Esparanza%252C_Sud%C3%A1frica%252C_2018-07-23%252C_DD_85.jpg.webp)