Tironian notes

Tironian notes (Latin: notae Tironianae) are a form of thousands of signs that were formerly used in a system of shorthand (Tironian shorthand) dating from the 1st century BCE and named after Tiro, a personal secretary to Marcus Tullius Cicero, who is often credited as their inventor.[1] Tiro's system consisted of about 4,000 signs,[2] extended to 5,000 signs by others. During the medieval period, Tiro's notation system was taught in European monasteries and expanded to a total of about 13,000 signs.[3] The use of Tironian notes declined after 1100 but lasted into the 17th century. A few Tironian signs are still used today.[4][5]

| Tironian notes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | shorthand

|

| Creator | Marcus Tullius Tiro |

| Created | 60s BC |

Time period | 1st century BC – 16th century AD |

| Status | a few Tironian symbols are still in modern use |

| Languages | Latin |

| Unicode | |

| Et: U+204A, U+2E52; MUFI | |

Note on sign counts

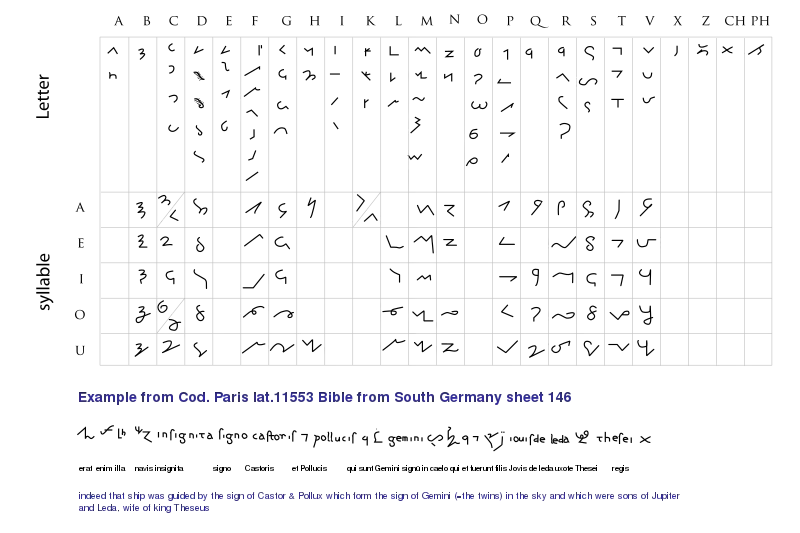

Tironian notes can be themselves composites (ligatures) of simpler Tironian notes, the resulting compound being still shorter than the word it replaces. This accounts in part for the large number of attested Tironian notes, and for the wide variation in estimates of the total number of Tironian notes. Further, the "same" sign can have other variant forms, leading to the same issue.

History

Development

Before Tironian shorthand became popularized, literature professor Anthony Di Renzo explains, "no true Latin shorthand existed." The only systematized form of abbreviation in Latin was used for legal notations (notae juris). This system, however, was deliberately abstruse and accessible only to people with specialized knowledge. Otherwise, shorthand was improvised for note-taking or writing personal communications, and some of these notations would not have been understood outside of closed circles. Some abbreviations of Latin words and phrases were commonly recognized, such as those of praenomina, and were typically used for inscriptions on monuments.[1]

Scholars infer that Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC) recognized the need for a comprehensive, standard Latin notation system after learning about the Greek shorthand system. Cicero presumably delegated the task of creating such a system for Latin to his slave and personal secretary Tiro. Tiro's position required him to quickly and accurately transcribe dictations from Cicero, such as speeches, professional and personal correspondence, and business transactions, sometimes while walking through the forum or during fast-paced and contentious government and legal proceedings.[1] Nicknamed "the father of stenography" by historians,[4] Tiro developed a highly refined and accurate method that used Latin letters and abstract symbols represented prepositions, truncated words, contractions, syllables, and inflections. According to Di Renzo: "Tiro then combined these mixed signs like notes in a score to record not just phrases, but, as Cicero marvels in a letter to Atticus, 'whole sentences.'"[1] Tiro's highly refined and accurate method became the first standardized and widely adopted system of Latin shorthand.[1] The system consisted of abbreviations and abstract symbols, which were either contrived by Tiro or borrowed from Greek shorthand.

Controversy

Dio Cassius attributes the invention of shorthand to Maecenas, and states that he employed his freedman Aquila in teaching the system to numerous others.[6] Isidore of Seville, however, details another version of the early history of the system, ascribing the invention of the art to Quintus Ennius, who he says invented 1100 marks (Latin: notae). Isidore states that Tiro brought the practice to Rome, but only used Tironian notes for prepositions.[7] According to Plutarch in "Life of Cato the Younger", Cicero's secretaries established the first examples of the art of Latin shorthand:[8]

This only of all Cato's speeches, it is said, was preserved; for Cicero, the consul, had disposed in various parts of the senate-house, several of the most expert and rapid writers, whom he taught to make figures comprising numerous words in a few short strokes; as up to that time they not used those we call shorthand writers, who then, as it is said, established the first example of the art.

Introduction

There are no surviving copies of Tiro's original manual and code, so knowledge of it is based on biographical records and copies of Tironian tables from the medieval period.[1] Historians typically date the invention of Tiro's system as 63 BC, when it was first used in official government business according to Plutarch in his biography of Cato the Younger in The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans.[9] Before Tiro's system was institutionalized, he used it himself as he was developing and fine-tuning it, which historians suspect may have been as early as 75 BC, when Cicero held public office in Sicily and needed his notes and correspondences to be written in code to protect sensitive information he gathered about corruption among other government officials there.[1]

There is evidence that Tiro taught his system to Cicero and his other scribes, and possibly to his friends and family, before it came into wide use. In "Life of Cato the Younger", Plutarch wrote that during Senate hearings in 65 BC relating to the first Catilinarian conspiracy, Tiro and Cicero's other secretaries were in the audience meticulously and rapidly transcribing Cicero's oration. On many of the oldest Tironian tables, lines from this speech were frequently used as examples, leading scholars to theorize it was originally transcribed using Tironian shorthand. Scholars also believe that in preparation for speeches, Tiro drafted outlines in shorthand that Cicero used as notes while speaking.[1]

Expansion

Isidore tells of the development of additional Tironian notes by various hands, such as Vipsanius, Philargius, and Aquila (as above), until Seneca systematized the various marks to be approximately 5000 in number.[7]

Use in the Middle Ages

Entering the Middle Ages, Tiro's shorthand was often used in combination with other abbreviations and the original symbols were expanded to 14,000 symbols during the Carolingian dynasty, but it quickly fell out of favor as shorthand became associated with witchcraft and magic and was forgotten until interest was rekindled by Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, in the 12th century.[10] In the 15th century Johannes Trithemius, abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Sponheim in Germany, discovered the notae Benenses: a psalm and a Ciceronian lexicon written in Tironian shorthand.[11]

The Tironian et can look very similar to an r rotunda, ⟨ꝛ⟩, depending on the typeface.

In Old English manuscripts, the Tironian et served as both a phonetic and morphological place holder. For instance, a Tironian et between two words would be phonetically pronounced ond and would mean 'and'. However, if the Tironian et followed the letter s, then it would be phonetically pronounced sond and mean 'water' (ancestral to Modern English sound in the geographical sense). This additional function of a phonetic as well as a conjunction placeholder has escaped formal Modern English; for example, one may not spell the word sand as s& (although this occurs in an informal style practised on certain Internet forums and sometimes in texting and other forms of instant messaging). This practice was distinct from the occasional use of &c. for etc., where the & is interpreted as the Latin word et ('and') and the c. is an abbreviation for Latin cetera ('[the] rest').

Current

A few Tironian symbols are still used today, particularly the Tironian et (⁊), used in Ireland and Scotland to mean 'and' (where it is called agus in Irish and agusan[12] in Scottish Gaelic), and in the z of viz. (for et in videlicet – though here the z is derived from a Latin abbreviation sign, encoded as a casing pair U+A76A Ꝫ and U+A76B ꝫ).

In blackletter texts (especially in German printing), it was still used in the abbreviation ⟨⁊c.⟩ = etc. (for et cetera) throughout the 19th century.

Support on computers

The use of Tironian notes on modern computing devices is not always straightforward. The Tironian et ⟨⁊⟩ is available at Unicode point U+204A, and can be made to display (e.g. for documents written in Irish or Scottish Gaelic) on a relatively wide range of devices: on Microsoft Windows, it can be shown in Segoe UI Symbol (a font that comes bundled with Windows Vista onwards); on macOS and iOS devices in all default system fonts; and on Windows, macOS, ChromeOS, and Linux in the free DejaVu Sans font (which comes bundled with ChromeOS and various Linux distributions). On the Microsoft Scottish Gaelic keyboard layout, the ⁊ can be entered by pressing AltGr+7 on Windows 11.[13]

Some applications and websites, such as the online edition of the Dictionary of the Irish Language, substitute the Tironian et with the box-drawing character U+2510 ┐, as it looks similar and displays widely. The numeral 7 is also used in informal contexts such as Internet forums and occasionally in print.[14]

A number of other Tironian signs have been assigned to the Private Use Area of Unicode by the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI), who also provide links to free typefaces that support their specifications.

| Preview | ⹒ | ⁊ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | TIRONIAN SIGN CAPITAL ET | TIRONIAN SIGN ET | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 11858 | U+2E52 | 8266 | U+204A |

| UTF-8 | 226 185 146 | E2 B9 92 | 226 129 138 | E2 81 8A |

| Numeric character reference | ⹒ | ⹒ | ⁊ | ⁊ |

Gallery

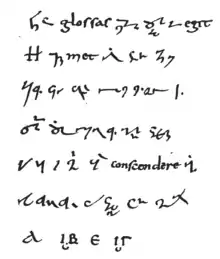

"Letter of Consolation for Departing Warriors", 9th century

"Letter of Consolation for Departing Warriors", 9th century Psalm 68. Manuscript, 9th century

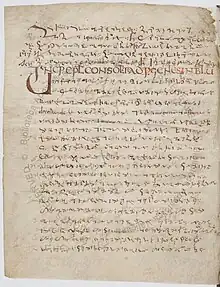

Psalm 68. Manuscript, 9th century Tironian note glossary from the 8th century, codex Casselanus. "Notae Senecae", Seneca's notes.

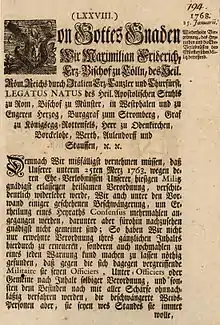

Tironian note glossary from the 8th century, codex Casselanus. "Notae Senecae", Seneca's notes. Tironian et in the abbreviation etc. at the end of the nobility title list. German printing, 1768

Tironian et in the abbreviation etc. at the end of the nobility title list. German printing, 1768 Irish Green postbox at Adare, County Limerick, with the P⁊Ꞇ logo

Irish Green postbox at Adare, County Limerick, with the P⁊Ꞇ logo

See also

References

- Di Renzo, Anthony (2000). "His Master's Voice: Tiro and the Rise of the Roman Secretarial Class" (PDF). Journal of Technical Writing & Communication. 30 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Job, Barbara. Schierholz, Stefan J. (ed.). "Kürzel" [Shorthand]. Wörterbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (WSK) Online (in German). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Guénin, Louis-Prosper; Guénin, Eugène (1908). Histoire de la sténographie dans l'antiquité et au moyen-âge; les notes tironiennes (in French). Paris: Hachette et cie. OCLC 301255530.

- Mitzschke, Paul Gottfried; Lipsius, Justus; Heffley, Norman P. (1882). Biography of the father of stenography, Marcus Tullius Tiro; together with the Latin letter, "De notis", concerning the origin of shorthand. Brooklyn, New York. OCLC 11943552.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kopp, Ulrich Friedrich; Bischoff, Bernhard (1965). Lexicon Tironianum (in German). Osnabrück: Zeller. OCLC 2996309.

- Dio Cassius. Roman History. 55.7.6

- Isidorus. Etymologiae or Originum I.21ff, Gothofred, editor

- Plutarch (1683). "Life of Cato the Younger". The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. Translated by Dryden, John.

- Bankston, Zach (2012). "Administrative Slavery in the Ancient Roman Republic: The Value of Marcus Tullius Tiro in Ciceronian Rhetoric". Rhetoric Review. 31 (3): 203–218. doi:10.1080/07350198.2012.683991. S2CID 145385697.

- Russon, Allien R. (15 August 2023). "Shorthand". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- King, David A. The Ciphers of the Monks: A Forgotten Number-notation of the Middle Ages.

- Dwelly, William; Robertson, Michael; Bauer, Edward. "Am Faclair Beag – Scottish Gaelic Dictionary". Faclair.

- "Scottish Gaelic Keyboard". Microsoft Learn. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Cox, Richard (1991). Brìgh nam Facal. Roinn nan Cànan Ceilteach. p. V. ISBN 978-0903204-21-7.

External links

- Wilhelm Schmitz: Commentarii notarum tironianarum, 1893 (Latin)

- Émile Chatelain: Introduction à la lecture des notes tironiennes, 1900 (French)

- Karl Eberhard Henke: Über Tironische Noten Manuscript B 16 of the Bibliothek der Monumenta Germaniae Historica, c. 1960 (German) (See 33. within for examples of composite Tironian notes.)

- Martin Hellmann: Supertextus Notarum Tironianarum Online dictionary of Tironian notes, based on Schmitz 1893 (German)