Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus (/ˈtaɪtəs/ TY-təs; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

| Titus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bust at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 24 June 79 – 13 September 81 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Vespasian | ||||||||

| Successor | Domitian | ||||||||

| Born | 30 December 39 Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Died | 13 September 81 (aged 41) Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Burial | Rome | ||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Flavian | ||||||||

| Father | Vespasian | ||||||||

| Mother | Domitilla | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

.png.webp) | ||

| Flavian dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

|

69–79 AD |

||

|

79–81 AD |

||

|

81–96 AD |

||

| Family | ||

|

||

|

||

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a military commander, serving under his father in Judea during the First Jewish–Roman War. The campaign came to a brief halt with the death of emperor Nero in 68, launching Vespasian's bid for the imperial power during the Year of the Four Emperors. When Vespasian was declared Emperor on 1 July 69, Titus was left in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion. In 70, he besieged and captured Jerusalem, and destroyed the city and the Second Temple. For this achievement Titus was awarded a triumph; the Arch of Titus commemorates his victory to this day and age.

During his father's rule, Titus gained notoriety in Rome serving as prefect of the Praetorian Guard, and for carrying on a controversial relationship with the Jewish queen Berenice. Despite concerns over his character, Titus ruled to great acclaim following the death of Vespasian in 79, and was considered a good emperor by Suetonius and other contemporary historians.

As emperor, Titus is best known for completing the Colosseum and for his generosity in relieving the suffering caused by two disasters, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 and a fire in Rome in 80. After barely two years in office, Titus died of a fever on 13 September 81. He was deified by the Roman Senate and succeeded by his younger brother Domitian.

Early life

Titus was born in Rome, probably on 30 December 39 AD, as the eldest son of Titus Flavius Vespasianus, commonly known as Vespasian, and Domitilla the Elder.[2] He had one younger sister, Domitilla the Younger (born 45), and one younger brother, Titus Flavius Domitianus (born 51), commonly referred to as Domitian.

Family background

Decades of civil war during the 1st century BC had contributed greatly to the demise of the old aristocracy of Rome, which was gradually replaced in prominence by a new Italian nobility during the early 1st century.[3] One such family was the gens Flavia, which rose from relative obscurity to prominence in only four generations, acquiring wealth and status under the Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Titus's great-grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, had served as a centurion under Pompey during Caesar's Civil War. His military career ended in disgrace when he fled the battlefield at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC.[4]

Nevertheless, Petro managed to improve his status by marrying the extremely-wealthy Tertulla, whose fortune guaranteed the upwards mobility of Petro's son Titus Flavius Sabinus I, Titus's grandfather.[5] Sabinus himself amassed further wealth and possible equestrian status through his services as tax collector in Asia and banker in Helvetia. By marrying Vespasia Polla, he allied himself to the more prestigious patrician gens Vespasia, ensuring the elevation of his sons Titus Flavius Sabinus II and Vespasian to the senatorial rank.[5]

The political career of Vespasian included the offices of quaestor, aedile and praetor and culminated with a consulship in 51, the year Domitian was born. As a military commander, he gained early renown by participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43.[6] What little is known of Titus's early life has been handed down by Suetonius, who recorded that he was brought up at the imperial court in the company of Britannicus,[7] the son of Emperor Claudius, who would be murdered by Nero in 55.

The story was even told that Titus was reclining next to Britannicus on the night he was murdered and sipped of the poison that was handed to him.[7] Further details on his education are scarce, but it seems he showed early promise in the military arts and was a skilled poet and orator both in Greek and Latin.[8]

Adult life

From around 57 to 59 he was a military tribune in Germania. He also served in Britannia and perhaps arrived about 60 with reinforcements needed after the revolt of Boudica. About 63, he returned to Rome and married Arrecina Tertulla, daughter of Marcus Arrecinus Clemens, a former Prefect of the Praetorian Guard. She died about 65.[9]

Titus then took a new wife of a much more distinguished family, Marcia Furnilla. However, Marcia's family was closely linked to the opposition to Nero. Her uncle Barea Soranus and his daughter Servilia were among those who perished after the failed Pisonian conspiracy of 65.[10] Some modern historians theorise that Titus divorced his wife because of her family's connection to the conspiracy.[11][12]

Titus never remarried and appears to have had multiple daughters,[13] at least one of them by Marcia Furnilla.[14] The only one known to have survived to adulthood was Julia Flavia, perhaps Titus's child by Arrecina, whose mother was also named Julia.[15] During this period Titus also practiced law and attained the rank of quaestor.[14]

Judaean campaigns

In 66, the Jews of the Judaea Province revolted against the Roman Empire. Cestius Gallus, the legate of Syria, was defeated at the battle of Beth-Horon and forced to retreat from Jerusalem.[16] The pro-Roman King Agrippa II and his sister Berenice fled the city to Galilee, where they later gave themselves up to the Romans.[17]

Nero appointed Vespasian to put down the rebellion, who was dispatched to the region at once with the Fifth Legion and Tenth Legion.[17] He was later joined at Ptolemais by Titus with the Fifteenth Legion.[18] With a strength of 60,000 professional soldiers, the Romans prepared to sweep across Galilee and march on Jerusalem.[18]

The history of the war was covered in detail by the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus in his work The War of the Jews. Josephus served as a commander in the city of Yodfat when the Roman army invaded Galilee in 67. After an exhausting siege which lasted 47 days, the city fell, with an estimated 40,000 killed. Titus, however, was not simply set on ending the war.[19]

Surviving one of several group suicides, Josephus surrendered to Vespasian and became a prisoner. He later wrote that he had provided the Romans with intelligence on the ongoing revolt.[20] By 68, the entire coast and the north of Judaea were subjugated by the Roman Army, with decisive victories won at Taricheae and Gamala, where Titus distinguished himself as a skilled general.[14][21]

Year of the Four Emperors

The last and most significant fortified city held by the Jewish resistance was Jerusalem. The campaign came to a sudden halt when news arrived of Nero's death.[22] Almost simultaneously, the Roman Senate had declared Galba, the governor of Hispania, as emperor. Vespasian decided to await further orders and sent Titus to greet the new princeps.[23]

Before reaching Italy, Titus learnt that Galba had been murdered and replaced by Otho, the governor of Lusitania, and that Vitellius and his armies in Germania were preparing to march on the capital, intent on overthrowing Otho. Not wanting to risk being taken hostage by one side or the other, he abandoned the journey to Rome and rejoined his father in Judaea.[24] Meanwhile, Otho was defeated in the First Battle of Bedriacum and committed suicide.[25]

When the news reached the armies in Judaea and Ægyptus, they took matters into their own hands and declared Vespasian emperor on 1 July 69.[26] Vespasian accepted and, after negotiations by Titus, joined forces with Gaius Licinius Mucianus, governor of Syria.[27] A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus, and Vespasian travelled to Alexandria, leaving Titus in charge to end the Jewish rebellion.[28][29] By the end of 69, the forces of Vitellius had been beaten, and Vespasian was officially declared emperor by the Senate on 21 December, thus ending the Year of the Four Emperors.[30]

Siege of Jerusalem

_La_distruzione_del_tempio_di_Gerusalemme_-Francesco_Hayez_-_gallerie_Accademia_Venice.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, the Jews had become embroiled in a civil war of their own by splitting the resistance in Jerusalem among several factions. The Sicarii, led by Menahem ben Judah, could hold on for long; the Zealots, led by Eleazar ben Simon, eventually fell under the command of the Galilean leader John of Gush Halav; and the other northern rebel commander, Simon Bar Giora, managed to gain leadership over the Idumeans.[31] Titus besieged Jerusalem. The Roman Army was joined by the Twelfth Legion, which had been previously defeated under Cestius Gallus, and from Alexandria, Vespasian sent Tiberius Julius Alexander, governor of Egypt, to act as Titus' second in command.[32]

Titus surrounded the city with three legions (Vth, XIIth and XVth) on the western side and one (Xth) on the Mount of Olives to the east. He put pressure on the food and water supplies of the inhabitants by allowing pilgrims to enter the city to celebrate Passover and then refusing them egress. Jewish raids continuously harassed the Roman Army, one of which nearly resulted in Titus being captured.[33]

After attempts by Josephus to negotiate a surrender had failed, the Romans resumed hostilities and quickly breached the first and second walls of the city.[34] To intimidate the resistance, Titus ordered deserters from the Jewish side to be crucified around the city wall.[35] By that time the Jews had been exhausted by famine, and when the weak third wall was breached, bitter street fighting ensued.[36]

The Romans finally captured the Antonia Fortress and began a frontal assault on the gates of the Second Temple.[37] As they breached the gate, the Romans set the upper and lower city aflame, culminating with the destruction of the Temple. When the fires subsided, Titus gave the order to destroy the remainder of the city, allegedly intending that no one would remember the name Jerusalem.[38] The Temple was demolished, Titus's soldiers proclaimed him imperator in honour of the victory.[39]

Jerusalem was sacked and much of the population killed or dispersed. Josephus claims that 1,100,000 people were killed during the siege, most of whom were Jewish.[40] Josephus's death toll assumptions are rejected as impossible by modern scholarship since about a million people then lived in the Land of Israel, half of them Jewish, and sizable Jewish populations remained in the area after the war was over, even in the hard-hit region of Judea.[41] However, 97,000 were captured and enslaved, including Simon Bar-Giora and John of Gischala.[40] Many fled to areas around the Mediterranean Sea. Titus reportedly refused to accept a wreath of victory, as he claimed that he had not won the victory on his own but had been the vehicle through which their God had manifested his wrath against his people.[42]

The Jewish diaspora during the Temple's destruction, according to Josephus, was in Parthia (Persia), Babylonia (Iraq), and Arabia, and some were beyond the Euphrates and in Adiabene (Kurdistan).[43]

Heir to Vespasian

Unable to sail to Italy during the winter, Titus celebrated elaborate games at Caesarea Maritima and Berytus and then travelled to Zeugma on the Euphrates, where he was presented with a crown by Vologases I of Parthia. While he was visiting Antioch, he confirmed the traditional rights of the Jews in that city.[44]

On his way to Alexandria, he stopped in Memphis to consecrate the sacred bull Apis. According to Suetonius, that caused consternation since the ceremony required Titus to wear a diadem, which the Romans associated with monarchy, and the partisanship of Titus's legions had already led to fears that he might rebel against his father. Titus returned quickly to Rome in the hope, according to Suetonius, of allaying any suspicions about his conduct.[45]

Upon his arrival in Rome in 71, Titus was awarded a triumph.[46] Accompanied by Vespasian and Domitian, Titus rode into the city, enthusiastically saluted by the Roman populace and preceded by a lavish parade containing treasures and captives from the war. Josephus describes a procession with large amounts of gold and silver carried along the route, followed by elaborate re-enactments of the war, Jewish prisoners and finally the treasures taken from the Temple of Jerusalem, including the Menorah and the Pentateuch.[47] Simon Bar Giora was executed in the Forum, and the procession closed with religious sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter.[48] The triumphal Arch of Titus, which stands at one entrance to the Forum, memorialises the victory of Titus.

With Vespasian declared emperor, Titus and his brother Domitian received the title of Caesar from the Senate.[49] In addition to sharing tribunician power with his father, Titus held seven consulships during Vespasian's reign[50] and acted as his secretary, appearing in the Senate on his behalf.[50] More crucially, he was appointed Praetorian prefect (commander of the Praetorian Guard), ensuring its loyalty to the emperor and further solidifying Vespasian's position as a legitimate ruler.[50]

In that capacity, Titus achieved considerable notoriety in Rome for his violent actions, frequently ordering the execution of suspected traitors on the spot.[50] When in 79, a plot by Aulus Caecina Alienus and Eprius Marcellus to overthrow Vespasian was uncovered, Titus invited Alienus to dinner and ordered him to be stabbed before he had even left the room.[50][51]

During the Jewish Wars, Titus had begun a love affair with Berenice, the sister of Agrippa II.[24] The Herodians had collaborated with the Romans during the rebellion, and Berenice herself had supported Vespasian in his campaign to become emperor.[52] In 75, she returned to Titus and openly lived with him in the palace as his promised wife. The Romans were wary of the eastern queen and disapproved of their relationship.[53] When the pair was publicly denounced by Cynics in the theatre, Titus acceded to the pressure and sent her away,[54] but his reputation suffered further regardless.

Emperor

Succession

Vespasian died of an infection on 23[55] or 24[56] June 79 AD, and was immediately succeeded by his son Titus.[57] He was the first Roman emperor to come to the throne after his own biological father. As Pharaoh of Egypt, Titus adopted the titulary Autokrator Titos Kaisaros Hununefer Benermerut (“Emperor Titus Caesar, the perfect and popular youth”).[58] Because of his many (alleged) vices, many Romans feared that he would be another Nero.[59] Against those expectations, however, Titus proved to be an effective emperor and was well loved by the population, who praised him highly when they found that he possessed the greatest virtues, instead of vices.[59]

One of his first acts as emperor was to order a halt to trials based on treason charges,[60] which had long plagued the principate. The law of treason, or law of majestas, was originally intended to prosecute those who had corruptly "impaired the people and majesty of Rome" by any revolutionary action.[61] Under Augustus, however, that custom had been revived and applied to cover slander and libel as well.[61] This led to numerous trials and executions under Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero, and the formation of networks of informers (delators), which terrorised Rome's political system for decades.[60]

Titus put an end to that practice against himself or anyone else and declared:

It is impossible for me to be insulted or abused in any way. For I do naught that deserves censure, and I care not for what is reported falsely. As for the emperors who are dead and gone, they will avenge themselves in case anyone does them a wrong, if in very truth they are demigods and possess any power.[62]

Consequently, no senators were put to death during his reign;[62] he thus kept to his promise that he would assume the office of Pontifex Maximus "for the purpose of keeping his hands unstained".[63] Informants were publicly punished and banished from the city. Titus further prevented abuses by making it unlawful for a person to be tried under different laws for the same offense.[60] Finally, when Berenice returned to Rome, he sent her away.[59]

As emperor, he became known for his generosity, and Suetonius states that upon realising he had brought no benefit to anyone during a whole day he remarked, "Friends, I have lost a day".[60]

Challenges

Although Titus's brief reign was marked by a relative absence of major military or political conflicts, he faced a number of major disasters. A few months after his accession, Mount Vesuvius erupted.[64] The eruption almost completely destroyed the cities and resort communities around the Bay of Naples. The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were buried under metres of stone and lava,[65] killing thousands.[66] Titus appointed two ex-consuls to organise and coordinate the relief effort and personally donated large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to aid the victims of the volcano.[60] Additionally, he visited Pompeii once after the eruption and again the following year.[67]

During the second visit, in spring of 80, a fire broke out in Rome and burned large parts of the city for three days and three nights.[60][67] Although the extent of the damage was not as disastrous as during the Great Fire of 64 and crucially spared the many districts of insulae, Cassius Dio records a long list of important public buildings that were destroyed, including Agrippa's Pantheon, the Temple of Jupiter, the Diribitorium, parts of the Theatre of Pompey, and the Saepta Julia among others.[67] Once again, Titus personally compensated for the damaged regions.[67] According to Suetonius, a plague also broke out during the fire.[60] The nature of the disease, however, and the death toll are unknown.

Meanwhile, war had resumed in Britannia, where Gnaeus Julius Agricola pushed further into Caledonia and managed to establish several forts there.[68] As a result of his actions, Titus received the title of imperator for the fifteenth time, between 9 September and 31 December 79 AD.[69]

His reign also saw the rebellion led by Terentius Maximus, one of several false Neros who appeared throughout the 70s.[70] Although Nero was primarily known as a universally-hated tyrant, there is evidence that for much of his reign, he remained highly popular in the eastern provinces. Reports that Nero had survived his overthrow were fuelled by the confusing circumstances of his death and several prophecies foretelling his return.[71]

According to Cassius Dio, Terentius Maximus resembled Nero in voice and appearance and, like him, sang to the lyre.[62] Terentius established a following in Asia Minor but was soon forced to flee beyond the Euphrates and took refuge with the Parthians.[62][70] In addition, sources state that Titus discovered that his brother Domitian was plotting against him but refused to have him killed or banished.[63][72]

Public works

Construction of the Flavian Amphitheatre, now better known as the Colosseum, was begun in 70 under Vespasian and was finally completed in 80 under Titus.[73] In addition to providing spectacular entertainments to the Roman populace, the building was also conceived as a gigantic triumphal monument to commemorate the military achievements of the Flavians during the Jewish Wars.[74]

The inaugural games lasted for a hundred days and were said to be extremely elaborate, including gladiatorial combat, fights between wild animals (elephants and cranes), mock naval battles for which the theatre was flooded, horse races and chariot races.[75] During the games, wooden balls were dropped into the audience, inscribed with various prizes (clothing, gold or even slaves), which could then be traded for the designated item.[75]

Adjacent to the amphitheatre, within the precinct of Nero's Golden House, Titus had also ordered the construction of a new public bath house, the Baths of Titus.[75] Construction of the building was hastily finished to coincide with the completion of the Flavian Amphitheatre.[59]

Practice of the imperial cult was revived by Titus, but apparently, it met with some difficulty since Vespasian was not deified until six months after his death.[76] To honour and glorify the Flavian dynasty further, foundations were laid for what would later become the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, which was finished by Domitian.[77][78]

Death

At the closing of the games, Titus officially dedicated the amphitheatre and the baths in what was his final recorded act as Emperor.[72] He set out for the Sabine territories but fell ill at the first posting station[79] where he died of a fever, reportedly in the same farmhouse as his father.[80] Allegedly, the last words he uttered before passing away were "I have made but one mistake".[72][79]

Titus had ruled the Roman Empire for just over two years: from the death of his father in 79 to his own on 13 September 81.[72] He was succeeded by Domitian, whose first act as emperor was to deify his brother.[81]

Historians have speculated on the exact nature of his death and to which mistake Titus alluded in his final words. Philostratus wrote that he was poisoned by Domitian with a sea hare (Aplysia depilans) and that his death had been foretold to him by Apollonius of Tyana.[82] Suetonius and Cassius Dio maintain that he died of natural causes, but both accuse Domitian of having left the ailing Titus for dead.[72][81] Consequently, Dio believed the mistake to refer to not having Titus's brother executed when he was found to be openly plotting against him.[72]

The Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 56b) attributes Titus's death to an insect that flew into his nose and picked at his brain for seven years in a repetition of another legend referring to the biblical King Nimrod.[83][84][85] According to Rabbinic literature, Titus was a descendant of Esau and dared to challenge the Lord.[86] Jewish tradition says that Titus was plagued by God for destroying the second Temple and died as a result of a gnat going up his nose, causing a large growth inside of his brain that killed him.[87][88] A story is recorded in which Onkelos, a nephew of the Roman emperor Titus who destroyed the Second Temple, intent on converting to Judaism, summons up spirits to help make up his mind. Each describes his punishment in the afterlife."Onkelos son of Kolonikos ... went and raised Titus from the dead by magical arts, and asked him; 'Who is most in repute in the [other] world? He replied: Israel. What then, he said, about joining them? He said: Their observances are burdensome and you will not be able to carry them out. Go and attack them in that world and you will be at the top as it is written, Her adversaries are become the head etc.; whoever harasses Israel becomes head. He asked him: What is your punishment [in the other world]? He replied: What I decreed for myself. Every day my ashes are collected and sentence is passed on me and I am burnt and my ashes are scattered over the seven seas..."[89]

Flavian family tree

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Historiography

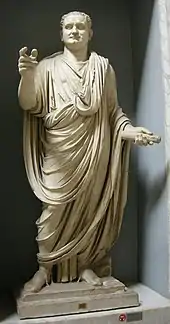

.jpg.webp)

Titus's record among ancient historians stands as one of the most exemplary of any emperor. All surviving accounts from the period, many of them written by his own contemporaries, present a highly favourable view toward Titus. His character has especially prospered in comparison with that of his brother Domitian.

The Wars of the Jews offers a first-hand eyewitness account of the Jewish rebellion and the character of Titus. The neutrality of Josephus's writings has come into question, however, as he was heavily indebted to the Flavians. In 71, he arrived in Rome in the entourage of Titus, became a Roman citizen and took on the Roman nomen Flavius and praenomen Titus from his patrons. He received an annual pension and lived in the palace.[90]

It was in Rome and under Flavian patronage that Josephus wrote all of his known works. The War of the Jews is heavily slanted against the leaders of the revolt by portraying the rebellion as weak and unorganised and even blaming the Jews for causing the war.[91] His credibility as a historian later came under fire.[92]

Another contemporary of Titus was Publius Cornelius Tacitus, who started his public career in 80 or 81 and credits the Flavian dynasty with his elevation.[93] The Histories, his account of the period, was published during the reign of Trajan. Unfortunately only the first five books from this work have survived, with the text on Titus's and Domitian's reign entirely lost.

Suetonius Tranquilius gives a short but highly-favourable account on Titus's reign in The Lives of Twelve Caesars,[94] emphasising his military achievements and his generosity as emperor and in short describing him as follows:

Titus, of the same surname as his father, was the delight and darling of the human race; such surpassing ability had he, by nature, art, or good fortune, to win the affections of all men, and that, too, which is no easy task, while he was emperor.[94]

Finally, Cassius Dio wrote his Roman History over 100 years after the death of Titus. He shares a similar outlook as Suetonius, possibly even using the latter as a source, but is more reserved by noting:

His satisfactory record may also have been due to the fact that he survived his accession but a very short time, for he was thus given no opportunity for wrongdoing. For he lived after this only two years, two months and twenty days—in addition to the thirty-nine years, five months and twenty-five days he had already lived at that time. In this respect, indeed, he is regarded as having equalled the long reign of Augustus, since it is maintained that Augustus would never have been loved had he lived a shorter time, nor Titus had he lived longer. For Augustus, though at the outset he showed himself rather harsh because of the wars and the factional strife, was later able, in the course of time, to achieve a brilliant reputation for his kindly deeds; Titus, on the other hand, ruled with mildness and died at the height of his glory, whereas, if he had lived a long time, it might have been shown that he owes his present fame more to good fortune than to merit.[57]

Pliny the Elder, who later died during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius,[95] dedicated his Naturalis Historia to Titus.[96]

In contrast to the ideal portrayal of Titus in Roman histories, Jewish memory has "Titus the Wicked" remembered as an evil oppressor and destroyer of the Temple. For example, one legend in the Babylonian Talmud describes Titus as having had sex with a prostitute on a Torah scroll inside the Temple during its destruction.[97]

In later arts

The war in Judaea and the life of Titus, particularly his relationship with Berenice, have inspired writers and artists through the centuries. The bas-relief in the Arch of Titus has been influential in the depiction of the destruction of Jerusalem, with the Menorah frequently being used to symbolise the looting of the Second Temple.

Literature

- The early mediaeval Christian text Vindicta Salvatoris anachronistically portrays Titus as Roman client-king of Libya, north of Judah.[98]

- Bérénice, a play by Jean Racine (1670), which focuses on the love affair between Titus and Berenice.

- Tite et Bérénice, a play by Pierre Corneille, which was in competition with Racine the same year and concerns the same subject matter.

- Titus and Berenice, a 1676 play by Thomas Otway

- La clemenza di Tito, an opera by Mozart, which centres around a plot to kill Emperor Titus instigated by Vitellia, the daughter of Vitellius, to gain what she believes to be her rightful place as Queen.

- The Josephus Trilogy, novels by Lion Feuchtwanger, about the life of Flavius Josephus and his relation with the Flavian dynasty.

- Der jüdische Krieg (Josephus), 1932

- Die Söhne (The Jews of Rome), 1935

- Der Tag wird kommen (The day will come, Josephus and the Emperor), 1942

- The Marcus Didius Falco novels, which take place during the reign of Vespasian.

- Titus figures prominently in "The Pearl-Maiden", a novel by H. Rider Haggard, first published in 1901.

Paintings and visual arts

- The Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1846). Oil on canvas, 585 x 705 cm. Neue Pinakothek, Munich. An allegorical depiction of the destruction of Jerusalem, dramatically centered around the figure of Titus.

- The Destruction and Sack of the Temple of Jerusalem by Nicolas Poussin (1626). Oil on canvas, 145.8 x 194 cm. Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Depicts the destruction and looting of the Second Temple by the Roman army led by Titus.

- The Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem by Francesco Hayez (1867). Oil on canvas, 183 x 252 cm. Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Venice. Depicts the destruction and looting of the Second Temple by the Roman army.

- The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans Under the Command of Titus, A.D. 70 by David Roberts (1850). Oil on canvas, 136 x 197 cm. Private collection. Depicts the burning and looting of Jerusalem by the Roman army under Titus.

- The Triumph of Titus and Vespasian by Giulio Romano (1540). Oil on wood, 170 x 120 cm. Louvre, Paris. Depicts Titus and Vespasian as they ride into Rome on a triumphal chariot, preceded by a parade carrying spoils from the war in Judaea. The painting anachronistically features the Arch of Titus, which was not completed until the reign of Domitian.

- The Triumph of Titus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1885). Oil on canvas. Private collection. This painting depicts the triumphal procession of Titus and his family. Alma-Tadema was known for his meticulous historical research on the ancient world.[99] Vespasian, dressed as Pontifex Maximus, walks at the head of his family, followed by Domitian and his first wife Domitia Longina, who he had only recently married. Behind Domitian follows Titus, dressed in religious regalia. An exchange of glances between Titus and Domitia suggests an affair which historians have speculated upon.[72][79]

- Rear Panel of the Franks Casket. Northumbrian, early 8th century. Whale's bone carving with Anglo-Saxon runic inscription, 22.9 x 19 cm. British Museum, London. Titus leads Roman army into Jerusalem and captures Temple. Inhabitants flee into exile, judgement is passed on offenders, and captives are led away.

References

- Hammond, p. 27.

- Suetonius claims Titus was born in the year Caligula was assassinated, 41. However, this contradicts his statement that Titus died in his 42nd year, as well as Cassius Dio, who notes that Titus was 39 at the time of his accession. See Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 1, 11; Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.18; and Brian Jones; Robert Milns (2002). Suetonius: The Flavian Emperors: A Historical Commentary. London: Bristol Classical Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-85399-613-9.

- Jones (1992), p. 3

- Jones (1992), p. 1

- Jones (1992), p. 2

- Jones, (1992), p. 8

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 2

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 3

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 4, with Jones and Milns, pp. 95–96

- Tacitus, Annals XVI.30–33

- Gavin Townend, "Some Flavian Connections", The Journal of Roman Studies (1961), p. 57. See Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 4

- Jones (1992), p. 11

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana VII.7

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 4

- Jones and Milns, pp. 96, 167.

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews II.19.9

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews III.1.2

- Josephus, The War of the Jews III.4.2

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews III.7.34

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews III.8.8

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews III.10

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews IV.9.2

- Tacitus, Histories II.1

- Tacitus, Histories II.2

- Tacitus, Histories II.41–49

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews IV.10.4

- Tacitus, Histories II.5

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews IV.11.1

- Tacitus, Histories II.82

- Tacitus, Histories IV.3

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews V.1.4

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews V.1.6

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews V.2.2

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews V.6–V.9

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews V.11.1

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.2–VI.3

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.4.1

- Sulpicius Severus, Chronicles II.30.6–7. For Tacitus as the source, see T.D. Barnes (July 1977). "The Fragments of Tacitus' Histories". Classical Philology. 72 (3): 224–231, pp. 226–228. doi:10.1086/366355. S2CID 161875316.

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.6.1

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.9.3

- Schwartz, Seth (1984). "Political, social and economic life in the land of Israel". In Davies, William David; Finkelstein, Louis; Katz, Steven T. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0521772488.

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6.29 Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Josephus. BJ. 1.1.5.

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VII.3.1, VII.5.2

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 5

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXV.6

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VII.5.5

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VII.5.6

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXV.1

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 6

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXV.16

- Tacitus, Histories II.81

- Schalit, A. (2007). Berenice. In M. Berenbaum & F. Skolnik (Eds.), Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 410–411). Macmillan Reference US.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXV.15

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, "Life of Vespasian" §24

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.17

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.18

- "Titus". The Royal Titulary of Ancient Egypt. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 7

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 8

- Tacitus, Annals I.72

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.19

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 9

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.22

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.23

- The exact number of casualties is unknown, but estimates of the population of Pompeii range between 10,000 ("Engineering of Pompeii: Ruins Reveal Roman Technology for Construction, Transportation, and Water Distribution". Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2009.) and 25,000 (), with at least 1000 bodies currently recovered in and around the city ruins.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.24

- Tacitus, Agricola 22

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.20

- Tacitus, Histories I.2

- Sanford, Eva Matthews (1937). "Nero and the East". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 48: 75–103. doi:10.2307/310691. JSTOR 310691.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.26

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (1st ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-06-430158-9.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998. pp. 276–282. ISBN 978-0-19-288003-1.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.25

- Coins bearing the inscription Divus Vespasianus were not issued until 80 or 81 by Titus.

- Jones, Brian W. The Emperor Titus. New York: St. Martin's P, 1984. 143.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Domitian 5

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 10

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 11

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Domitian 2

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6.32 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tractate Gittin 56b". www.sefaria.org.il.

- Rosner, Fred. Medicine in the Bible and Talmud. p. 76. Pub. 1995, KTAV Publishing House, ISBN 0-88125-506-8. Extract viewable at ()

- Wikisource:Page:Legends of Old Testament Characters.djvu/178

- Tituss Death Chabad

- Quinn, Thomas (Director) (26 June 1995). Urban Legends: Season 3 Episode 1 [Television series]. United States. FilmRise.

- "Titus's Death". Chabad.org. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Babylonian Talmud Gittin 56b–57a. 1935 Soncino edition

- Josephus, The Life of Flavius Josephus 76

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews II.17

- Josephus, Flavius, The Jewish War, tr. G.A. Williamson, introduction by E. Mary Smallwood. New York, Penguin, 1981, p. 24

- Tacitus, Histories I.1

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 1

- The Destruction of Pompeii, 79 AD, Translation of Pliny's letters. Original.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories Preface

- Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 56b)

- Ehrman and Pleše (2011), p. 523.

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth (March 2002). "Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Modern City of Ancient Rome". The Art Bulletin. 84 (1): 115–129. doi:10.2307/3177255. JSTOR 3177255.

Sources

- Hammond, Mason (1957). "Imperial Elements in the Formula of the Roman Emperors during the First Two and a Half Centuries of the Empire". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 25: 19–64. doi:10.2307/4238646. JSTOR 4238646.

- Jones, Brian W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0.

- Brian Jones; Robert Milns (2002). Suetonius: The Flavian Emperors: A Historical Commentary. London: Bristol Classical Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-85399-613-9.

- Ehrman, Bart D.; Pleše, Zlatko (2011). The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973210-4.

apocryphal gospels texts and translations.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus, Latin text with English translation

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Books 65 and 66, English translation

- Josephus, The War of the Jews, English translation

- Tacitus, Histories, Books 2, 4 and 5, English translation

Secondary material

- Coinage of Titus at Wildwinds.com

- A private collection of coins minted by Titus

- Biography of Titus at roman-emperors.org

- Wayback Machine (Austin Simmons, The Cipherment of the Franks Casket) Titus is twice depicted on the back side of the Franks Casket.

External links

Media related to Titus (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Titus (category) at Wikimedia Commons- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 1032.