2008 Atlantic hurricane season

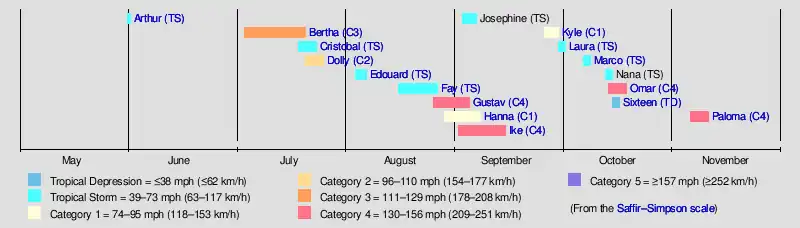

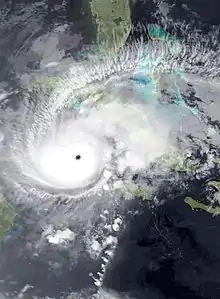

The 2008 Atlantic hurricane season was the most destructive Atlantic hurricane season since 2005, causing over 1,000 deaths and nearly $50 billion (2008 USD) in damage.[nb 1] The season ranked as the third costliest ever at the time, but has since fallen to ninth costliest. It was an above-average season, featuring sixteen named storms, eight of which became hurricanes, and five which further became major hurricanes.[nb 2] It officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the formation of Tropical Storm Arthur caused the season to start one day early. It was the only year on record in which a major hurricane existed in every month from July through November in the North Atlantic. Bertha became the longest-lived July tropical cyclone on record for the basin, the first of several long-lived systems during 2008.

| 2008 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 31, 2008 |

| Last system dissipated | November 10, 2008 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Ike |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 935 mbar (hPa; 27.61 inHg) |

| By maximum sustained winds | Gustav |

| • Maximum winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 941 mbar (hPa; 27.79 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 17 |

| Total storms | 16 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 5 |

| Total fatalities | 1,073 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $48.855 billion (2008 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The season was devastating for Haiti, where nearly 800 people were killed by four consecutive tropical cyclones (Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike), especially Hurricane Hanna, in August and September. These four storms caused about $1 billion in damage in Haiti alone. The precursor to Kyle and the outer rain bands of Paloma also impacted Haiti. Cuba also received extensive impacts from Gustav, Ike, and Paloma, with Gustav and Ike making landfall in the country at major hurricane intensity and Paloma being a Category 2 when striking the nation. More than $10 billion in damage and 8 deaths occurred there.

Ike was the most destructive storm of the season, as well as the strongest in terms of minimum barometric pressure, devastating Cuba as a major hurricane and later making landfall near Galveston, Texas, as a large high-end Category 2 hurricane. One very unusual feat was a streak of tropical cyclones affecting land, with all but one system impacting land in 2008. The unusual number of storms with impact led to one of the deadliest and destructive seasons in the history of the Atlantic basin, especially with Ike, as its overall damages made it the second-costliest Atlantic hurricane on record at the time, although it has since been surpassed by several hurricanes.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| CSU | Average (1950–2000)[2] | 9.6 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| NOAA | Average (1950–2005)[3] | 11.0 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| Record high activity[4] | 30 | 15 | 7 | |

| Record low activity[4] | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| CSU | December 7, 2007 | 13 | 7 | 3 |

| TSR | December 10, 2007 | 15.4 (±4.7) | 8.3 (±3.0) | 3.7 (±1.8) |

| WSI | January 3, 2008 | 14 | 7 | 3 |

| TSR | April 7, 2008 | 14.8 (±4.1) | 7.8 (±2.7) | 3.5 (±1.8) |

| CSU | April 9, 2008 | 15 | 8 | 4 |

| WSI | April 23, 2008 | 14 | 8 | 4 |

| NOAA | May 22, 2008 | 12–16 | 6–9 | 2–5 |

| CSU | June 3, 2008 | 15 | 8 | 4 |

| TSR | June 5, 2008 | 14.4 (±3.4) | 7.7 (±2.4) | 3.4 (±1.6) |

| UKMO | June 18, 2008 | 15* | N/A | N/A |

| WSI | July 2, 2008 | 14 | 8 | 4 |

| TSR | July 2, 2008 | 14.6 (±3.4) | 7.9 (±2.2) | 3.5 (±1.6) |

| WSI | July 23, 2008 | 15 | 9 | 4 |

| CSU | August 5, 2008 | 17 | 9 | 5 |

| TSR | August 5, 2008 | 18.2 (±2.9) | 9.7 (±1.7) | 4.5 (±1.4) |

| NOAA | August 7, 2008 | 14–18 | 7–10 | 3–6 |

| WSI | August 27, 2008 | 15 | 9 | 4 |

| Actual activity | 16 | 8 | 5 | |

| * July–November only: 15 storms observed in this period. | ||||

Noted hurricane experts Dr. Philip J. Klotzbach, Dr. William M. Gray, and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU) – as well as forecasters at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Met Office (UKMO), Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), Weather Services International (WSI) – issued forecasts of hurricane activity prior to the start of the season.[5][6][7][8]

Dr. Klotzbach's team (formerly led by Dr. Gray) defines the average number of storms per season (1950 to 2000) as 9.6 tropical storms, 5.9 hurricanes, and 2.3 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength in the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale). A normal season, as defined by NOAA, has 9 to 12 named storms, with 5 to 7 of those reaching hurricane strength, and 1 to 3 major hurricanes.[2][3]

Pre-season forecasts

The first forecast for the 2008 hurricane season was released by CSU on December 7, 2007. In its report, the organization predicted 13 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an annual Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of 115 units. The odds of a major hurricane landfall in the Caribbean and along the United States were projected to be above average.[2] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm strength.[9] The odds of a major hurricane landfall in the Caribbean and along the United States were projected to be above average in the CSU forecast.[2]

Three days later, TSR—a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London—called for a very active season featuring 15.4 (±4.7) named storms, 8.3 (±3.0) hurricanes, 3.7 (±1.8) major hurricanes, and a cumulative ACE index of 149 (±66) units. Mirroring CSU, the group assigned high probabilities that the United States and Lesser Antilles landfalling ACE index would be above average.[10] On January 3, 2008, WSI projected 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[11]

In April, CSU slightly raised their values owing to a favorable Atlantic sea surface temperature configuration during the preceding month, upping the projected numbers to 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[12] TSR, in contrast, slightly reduced their numbers on April 7 due to cooler projections for Atlantic Ocean temperatures compared to their December forecast.[13] WSI on April 23 raised the expected number of hurricanes from 7 to 8 and major hurricanes from 3 to 4 while leaving the number of named storms unchanged.[14] On May 22, the NOAA's Climate Prediction Center announced their first seasonal outlook for the 2008 season, highlighting 65 percent odds of an above-normal season, 25 percent odds for a near-normal season, and 10 percent odds of a below-average season. A range of 12 to 16 named storms, 6 to 9 hurricanes, and 2 to 5 major hurricanes was provided, each with 60 to 70 percent probability. The CPC, alongside TSR and CSU, highlighted the ongoing multi-decadal period of enhanced Atlantic tropical cyclone activity, the ongoing La Niña in the Pacific, and warmer than average ocean temperatures across the eastern tropical Atlantic as the basis for their predictions.[15]

Midseason outlooks

On June 3, CSU released an updated outlook for the season but left their values from April unchanged. Examining conditions in April and May, the organization compiled a list of hurricane seasons with similar conditions: 1951, 1961, 2000, and 2001.[16] TSR slightly lowered their numbers in their June 5 update but continued to predict an above-average season.[17] Meanwhile, on June 18, the UKMO released their seasonal forecast, assessing a 70 percent probability the number of tropical storms would fall between 10 and 20, with 15 tropical storms noted as the most likely value in 2008. No projections for the number of hurricanes, major hurricanes, or ACE were given.[18] On July 2, WSI held firm to their April forecast;[19] the organization was forced to slightly increase the number of named storms and hurricanes later that month.[20] On July 4, TSR slightly raised their forecast.[21] Following an active start to the season, CSU upped their predictions in an August 5 update, calling for 17 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 175 units.[5] TSR released their final outlook for the season that day, raising their values to 18.2 (±2.9) named storms, 9.7 (±1.7) hurricanes, 4.5 (±1.4) major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 191 (±42) units.[7] On August 7, NOAA's CPC raised their probability of an above-average season from 65 percent to 85 percent. The final outlook yielded a 67 percent chance of 14 to 18 named storms, 7 to 10 hurricanes, and 3 to 6 major hurricanes.[6] WSI, meanwhile, issued their final seasonal outlook on August 27, reaffirming their numbers from the previous month.[8]

Seasonal summary

The 2008 hurricane season officially began on June 1,[22] though Tropical Storm Arthur formed one day earlier.[23] The season was above-average, featuring 16 named storms, 8 of which intensified into hurricanes, while 5 of the hurricanes reached major hurricane status.[24] Despite a La Niña dissipating early in the summer months, atmospheric conditions remained favorable for tropical cyclogenesis, including abnormally low wind shear between 10°N and 20°N. Additionally, sea surface temperatures in the deep tropics and the Caribbean Sea were fifth warmest since 1950.[25] The season saw the first occurrence of major hurricanes in the months of July through November.[26] Four storms formed before the start of August,[24] and the season also had the earliest known date for three storms to be active on the same day: Hurricane Bertha, and Tropical Storms Cristobal and Dolly were all active on July 20.[27] This season was also one of only ten Atlantic hurricanes seasons on record to have a major hurricane form before August,[28] as well as one of only seven Atlantic seasons to feature a major hurricane in November.[29] The final tropical cyclone, Hurricane Paloma, degenerated into a remnant low-pressure area over Cuba on November 9,[30] three weeks before the season officially ended on November 30.[22]

The season was devastating for Haiti, where four consecutive tropical cyclones – Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike – killed at least 793 people and caused roughly $1 billion in damage.[31] Hurricane Ike was the most destructive storm of the season, as well as the strongest, devastating Cuba as a major hurricane and later making landfall near Galveston, Texas, at Category 2 (nearly Category 3) intensity. The cyclone caused a particularly devastating storm surge along the western Gulf Coast of the United States due to in part to its large size.[32] Ike was the second-costliest hurricane in the Atlantic at the time, but has since dropped to sixth following Sandy, Harvey, Irma, and Maria.[33] Hanna was the deadliest storm of the season, killing 533 people, mostly in Haiti.[34][35][36][37] Gustav was another very destructive storm, causing up to $8.31 billion in damage to Haiti, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Cuba, and the United States.[38][33] Dolly caused up to $1.6 billion in damage to south Texas and northeastern Mexico.[39][40] Bertha was an early season Cape Verde-type hurricane that became the longest-lived July North Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, though it caused few deaths and only minor damage.[41] The Atlantic basin tropical cyclones of 2008 collectively caused roughly $49.4 billion in damage and at least 1,074 fatalities.[42] At the time, the season ranked as the third costliest on record, behind only 2004 and 2005.[43] However, it has since fallen to eighth.

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.803 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | $120.425 billion | 2022 |

| 4 | ≥ $80.727 billion | 2021 |

| 5 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 6 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 7 | ≥ $51.114 billion | 2020 |

| 8 | ≥ $50.526 billion | 2018 |

| 9 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 10 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

Other notable storms included Tropical Storm Fay, which became the first Atlantic tropical cyclone to make landfall in the same U.S. state on 4 occasions; Tropical Storm Marco, the smallest Atlantic tropical cyclone on record;[26] Hurricane Omar, a powerful late-season major hurricane which caused moderate damage to the ABC islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands in mid-October;[44] and Hurricane Paloma, which became the third-strongest November hurricane in recorded history and caused about $454.4 million in damage to the Cayman Islands and Cuba.[29][45][46] The only storm of the season to not reach tropical storm status, Tropical Depression Sixteen, contributed to a significant flooding event in Central America, with the cyclone itself directly blamed for at least nine deaths.[47]

Overall, the season's activity was reflected with a total cumulative ACE rating of 146. This was well above the normal average, and nearly double the rating given to each of the two preceding seasons (79 – 2006; 74 – 2007).[48]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arthur

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 31 – June 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

In late May, a westward-moving tropical wave and the mid-level remnants of Tropical Storm Alma from the East Pacific combined over the northwestern Caribbean Sea. This led to the formation of Tropical Storm Arthur by 00:00 UTC on May 31. The cyclone reached its peak intensity with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) six hours after development, and it made landfall at 09:00 UTC on June 1 about halfway between Belize City, Belize, and Chetumal, Yucatán Peninsula, at that strength. Once inland, Arthur quickly lost organization and degenerated to a remnant area of low pressure around 00:00 UTC on June 2. It dissipated six hours later. In conjunction with Alma, Tropical Storm Arthur dropped over 12 in (300 mm) of rainfall across portions of Belize, destroying roads, washing out bridges, and damaging 714 homes. Total damage was estimated at $78 million, and five deaths were recorded.[23]

Hurricane Bertha

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 3 – July 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 952 mbar (hPa) |

A well-defined tropical wave left Africa on July 1 and organized into a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on July 3. Six hours later, it intensified into Tropical Storm Bertha, the easternmost tropical storm on record in the Atlantic during July. Steered on a west-northwest or northwest course, Bertha reached hurricane strength around 06:00 UTC on July 7. The cyclone then underwent a period of rapid intensification that brought it to its peak as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h) later that day. Structural changes and a more hostile environment caused the storm to fluctuate in intensity as it passed east of Bermuda. By July 19, however, the storm began to undergo extratropical transition, a process it completed by 12:00 UTC the next morning. The post-tropical storm continued northeast and merged with a larger extratropical low near Iceland on July 21. Lasting a duration of 17 days, Bertha became the longest-lived Atlantic tropical cyclone on record during the month of July.[41]

As the cyclone passed east of Bermuda, it produced strong wind gusts peaking at 91 mph (146 km/h).[41] Power lines were downed, cutting electricity to about 7,500 homes, and tree branches were snapped.[49] Heavy rainfall, reaching 4.77 in (121 mm) at L.F. Wade International Airport,[50] flooded roadways. Meanwhile, Bertha produced large waves and rip currents along the U.S. East Coast, resulting in 3 deaths offshore New Jersey and 57 water rescues in Atlantic City alone.[51] Fifty-five people were injured off the coast of Delaware while an additional four individuals were injured off North Carolina.[52] At Wrightsville Beach in particular, officials estimated at least 60 water rescues over a 48-hour span.[53] Over a seven-day period beginning on July 9, the storm contributed to 1,500 ocean rescues in Ocean City, Maryland.[41]

Tropical Storm Cristobal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 19 – July 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

A trough of low pressure, the remnants of an old frontal boundary, extended along the East Coast of the United States on July 15. The trough extended into the Gulf of Mexico the following day and resulted in the development of a circulation that subsequently crossed Florida on July 17. Once in the Atlantic, the system became better organized and coalesced into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on July 19. It intensified into Tropical Storm Cristobal twelve hours later. After passing close to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the storm continued northeast and reached peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) early on July 21, when an eye feature was evident on microwave imagery. Progressively cooler waters began to weaken Cristobal the next day, and it was then absorbed by a large extratropical cyclone south of Newfoundland around 12:00 UTC on July 23.[54]

The precursor disturbance to Cristobal produced up to 6 in (150 mm) of rain in Florida, blocking storm drains and causing street flooding.[55] Some 35–40 cars were pulled from submerged streets in Marco Island, with some vehicles submerged in as much as 2 ft (0.61 m) of water.[56] Generally lesser rainfall totals occurred across the Southeastern United States,[50] though record daily accumulations around 3.43 in (87 mm) resulted in minor flooding in Wilmington, North Carolina.[57] Moisture from the tropical cyclone became intertwined with an approaching frontal system, producing a maximum rainfall total of 6.5 in (170 mm) in Baccaro, Nova Scotia. Basements were flooded and roads were washed out along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia.[58]

Hurricane Dolly

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 20 – July 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off Africa on July 11. As the wave moved west into the Caribbean, it produced gale-force winds and its satellite presentation resembled that of a tropical storm at times. However, the system did not develop a well-defined circulation until around 12:00 UTC on July 20, at which time it was designated as Tropical Storm Dolly about 310 mi (500 km) east of Chetumal, Quintana Roo. On a northwest course, the cyclone failed to organize initially; however, a more conducive environment in the Gulf of Mexico allowed Dolly to attain hurricane strength by 00:00 UTC on July 23 and reach its peak as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) twelve hours later. Dry air and cooler waters eroded the storm's eyewall after peak intensity, but Dolly still harbored winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) at its landfall on South Padre Island, Texas, at 18:20 UTC. It made a second landfall on the Texas mainland at a slightly reduced strength two hours later. Once inland, Dolly weakened to a tropical storm early on July 24 and ultimately degenerated to a remnant low around 00:00 UTC on July 26. The remnant low turned north and crossed the Mexico–United States border before losing its identity over New Mexico early on July 27.[59]

In its early stages, mudslides generated by heavy rainfall from the storm caused 21 deaths in Guatemala.[60] As the storm progressed across the Yucatán Peninsula, it produced significant beach erosion in Cancún.[61] Offshore, the body of a fisherman was recovered while three others were purported missing.[62] Offshore the Florida Panhandle, one person drowned in rough surf. In Texas, the hurricane caused moderate structural damage to the roofs of homes on South Padre Island, where maximum sustained winds of 78 mph (126 km/h), gusting to 107 mph (172 km/h), were recorded. Some buildings of lesser construction were severely damaged as well. Extensive damage to trees and utility poles occurred throughout Cameron and Willacy counties. Six weak tornadoes or waterspouts were recorded, but generally minor damage was observed. Widespread heavy rainfall occurred throughout southern Texas, with a concentration of 15 in (380 mm) near Harlingen; this rainfall caused severe inland flooding. Farther south in Mexico, a hurricane research team east of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, recorded sustained winds of 96 mph (154 km/h), gusting to 119 mph (192 km/h).[59] In the city itself, downed power lines fell into floodwaters, electrocuting a man.[63] The remnants of the storm heavy impacted Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, where five homes and a historic church were collapsed and about 2,840 acres (1,150 hectares) of corn and barley were ruined.[64] Farther north in New Mexico, an estimated 350–500 structures were damaged, roads and bridges were washed out, and one man was swept away by the swollen Rio Ruidoso river.[65] In nearby El Paso, Texas, homes and streets were flooded, and one indirect death occurred when a driver rolled over after hitting a puddle.[66] Overall, Dolly caused at least $1.6 billion in damage, with $1.3 billion in the United States and $300 million in Mexico.[39][40]

Tropical Storm Edouard

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 3 – August 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

A trough developed across the northern Gulf of Mexico on August 2 and quickly developed into a tropical depression about 85 miles (137 km) southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River around 12:00 UTC on August 3. The depression moved westward and intensified into Tropical Storm Edouard on August 4. The impacts of northerly wind shear initially curtailed intensification; the following day, however, a more favorable environmental regime allowed the storm to attain maximum winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). Edouard made landfall near the McFaddin and Texas Point National Wildlife Refuges at 12:00 UTC on August 5 at peak strength. The system quickly weakened once inland and was downgraded to a tropical depression early on August 6 before degenerating into a remnant low at 06:00 UTC that day. It continued to move northwestward across Texas and dissipated around 00:00 UTC on August 7.[67]

Rough surf and rip currents led to the deaths of three men in Panama City Beach, Florida,[68][69][70] a fourth man in Perdido Key,[71] a fifth man at Orange Beach, Alabama,[72] and a sixth man near the mouth of the Mississippi River.[67] Wind gusts in Louisiana peaked at 62 mph (100 km/h), ripping the roofs of mobile homes, downing numerous trees, and toppling power lines across Cameron, Calcasieu, and Vermilion parishes. Along the coastline, storm tides generally varied between 4–5 ft (1.2–1.5 m), with a peak of 5.09 ft (1.55 m) near Intracoastal City. This contributed to minor inland flooding.[73] In Texas, rainfall peaked at 6.48 in (165 mm) near Baytown, leading to the inundation of dozens of homes. Several roadways, including a portion of Interstate 10, were closed across Chambers and Harris counties.[67] Sustained winds of 56 mph (90 km/h), gusting to 71 mph (114 km/h), brought down trees and power lines while inflicting minor roof damage to hundreds of homes.[74] Overall Edouard caused about $800,000 in damage, with about $350,000 in Louisiana and $450,000 in Texas.[75][76]

Tropical Storm Fay

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 15 – August 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged from Africa on August 6 and moved swiftly across the Atlantic, developing into a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 15 while near the northwestern tip of Puerto Rico. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Fay as it struck the coastline of Haiti, and it maintained its status as a minimal tropical storm while progressing through the Cayman Trough and into south-central Cuba. Fay curved north and zigzagged across Florida, making a record four separate landfalls in the state. The first occurred near Key West on August 18 and the second just east of Cape Romano on August 19. While inland over Lake Okeechobee, Fay developed a well-defined eye and reached peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). The third landfall occurred near Flagler Beach on August 21 and the final southwest of Carrabelle on August 23. The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression in the Florida Panhandle on August 24 and moved northwest into Mississippi before making an abrupt turn to the northeast the following day. It merged with a frontal boundary and became extratropical around 06:00 UTC on August 27. The low was ultimately absorbed by a larger extratropical system over Kentucky early the next morning.[77]

Throughout the Caribbean, Fay contributed to at least 16 deaths: 10 in Haiti,[34] 5 in the Dominican Republic,[77] and 1 in Jamaica.[78] Many of these deaths were resultant from the storm's prolific rainfall, with numerous weather stations across the Dominican Republic and Cuba reporting accumulations of 7–10 in (180–250 mm); Agabama, Cuba, recorded a localized maximum of 18.23 in (463 mm). The combination of heavy rainfall and gusty winds resulted in over 2,400 homes being damaged across the Dominican Republic. Similar destruction was reported in Haiti, particularly on Gonâve Island. As Fay meandered across Florida, it produced widespread torrential rainfall there, with accumulations peaking at a record 27.65 in (702 mm) in the city of Melbourne. While run-off ultimately helped replenish Lake Okeechobee and surrounding reservoirs,[77] the immediate impact of the rain event was more destructive. Thousands of residences were inundated,[79] some with as much as 5 ft (1.5 m) of water, and sewage systems were congested. Numerous trees were felled, and downed power lines cut electricity to tens of thousands of homes.[80] Fay was a prolific tornado producer, with 81 confirmations across 5 states: 19 in Florida, 17 in Georgia, 16 in North Carolina, 15 in Alabama, and 14 in South Carolina. A majority were short-lived and weak.[77] Overall, Fay caused seventeen deaths in the United States: fifteen in Florida,[81] one in Georgia,[82] and one in Alabama.[83] Throughout all areas impacted, Fay caused about $560 million in damage.[77]

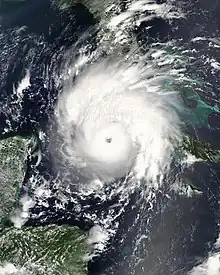

Hurricane Gustav

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min); 941 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed Africa on August 13, coalescing into a tropical depression south of Puerto Rico by 00:00 UTC on August 25 and intensifying into Tropical Storm Gustav twelve hours later. With a small inner core, the system rapidly strengthened to a hurricane early on August 26 before striking the southwestern peninsula of Haiti later that day. Gustav weakened while traversing Haiti and Jamaica but quickly restrengthened over the northwestern Caribbean, reaching winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) before making landfall on the Isle of Youth, and striking the mainland just east of Los Palacios, Cuba, with winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) later on August 30. Plagued by wind shear and dry air, the hurricane did not re-intensify over the Gulf of Mexico, instead making a final landfall near Cocodrie, Louisiana, at 15:00 UTC on September 1 with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h). Gustav continued northwest, weakening to a tropical depression over northern Louisiana before merging with a cold front over northern Arkansas around 12:00 UTC on September 4. The remnants accelerated northeast and merged with another extratropical low over the Great Lakes later on September 5.[38]

Throughout the Dominican Republic, over 1,239 homes were damaged, of which 12 were destroyed, and about 50 communities were isolated. Eight people were killed in a mudslide.[84] In neighboring Haiti, some 10,250 homes were damaged, including about 2,100 that were destroyed.[85] Eighty-five people were killed.[34] The storm caused $210 million in damage across Jamaica and resulted in 15 deaths.[38] The impact of Gustav was ruinous across the Isle of Youth and mainland Cuba, where sustained winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) and gusts up to 211 mph (340 km/h) resulted in damage to 120,509 structures (about 21,941 beyond repair).[45] The 211 mph (340 km/h) wind gust, observed at Paso Real de San Diego weather station in Pinar del Río Province, was the second highest wind gust ever recorded on land in a tropical cyclone, behind only Cyclone Olivia's 253 mph (407 km/h) gust on Barrow Island, Australia.[86] A total of 140 electrical towers were destroyed, laying waste to 809 mi (1,302 km) of power lines and cutting power to much of the area. Dozens of residents were injured but no deaths occurred. The estimated cost of the storm fell just shy of $2.1 billion.[45] Upon striking the United States, Gustav produced strong winds that damaged the roofs and windows of many structures,[87] as well as a large storm surge along the coastline of Louisiana which overtopped levees and floodwalls in New Orleans. Widespread heavy rainfall contributed to significant inland flooding from Louisiana into Arkansas. Tornadoes were confirmed throughout the region, including 21 in Mississippi, 11 in Louisiana, 6 in Florida, 2 in Arkansas, and 1 in Alabama. In total, Gustav cost $6 billion in the United States and killed 53 people: 48 in Louisiana, 4 in Florida, and 1 at sea.[38][33]

Hurricane Hanna

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 977 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave entered the Atlantic on August 19, leading to the formation of a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on August 28 approximately 315 mi (505 km) east-northeast of the northernmost Leeward Islands. Twelve hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Hanna. Interaction between the cyclone and an upper-level low kept Hanna fairly steady-state for several days, with its appearance briefly resembling that of a subtropical storm. Meanwhile, a building ridge over the eastern United States forced the storm to dive south. A reprieve in upper-level winds allowed Hanna to attain hurricane strength at 18:00 UTC on September 1 and reach peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) six hours later. However, the aforementioned ridge soon began to impart northerly wind shear, and the cyclone weakened accordingly. A second upper-level low caused Hanna to conduct a counter-clockwise loop north of Haiti before reaching the western periphery of the subtropical ridge, sending the storm ashore near the North Carolina–South Carolina border at 07:20 UTC on September 6 with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). It curved northeast once inland, merging with one cold front over southern New England and a second near Newfoundland.[37]

Hanna produced heavy rainfall across mountainous sections of Puerto Rico, leading to mudslides that damaged bridges and roads. Strong winds downed trees and power lines. Damage across the Turks and Caicos Islands in the wake of the storm was presumed to have been minor—confined to some roof damage to homes—but damage assessments were limited given the impact of Hurricane Ike less than a week later. Across Hispaniola, torrential rainfall exacerbated flooding that had already occurred during Tropical Storm Fay and Hurricane Gustav. While the exact death toll is indiscernible due to the quick succession of tropical cyclones,[37] Hanna is believed to have killed at least 529 people in Haiti, most in the commune of Gonaïves, as well as 1 person in the Dominican Republic.[34] Along the coastline of the United States, rip currents killed one person at Kure Beach, North Carolina and another in Spring Lake, New Jersey.[35][36] Gusty winds downed trees and power lines that cut electricity along the Eastern seaboard. Storm surge and heavy rainfall contributed to flooding, particularly in low-lying locales and across New Hampshire. One person drowned in a South Carolina drainage ditch.[88] Total damage was estimated at $160 million.[37]

Hurricane Ike

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 935 mbar (hPa) |

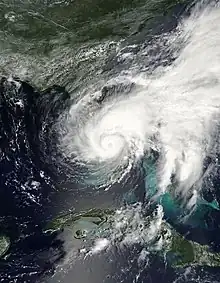

At 06:00 UTC on September 1, the season's ninth tropical depression developed from a well-defined tropical wave that left Africa on August 28. A strong subtropical ridge to the depression's north directed it on a west-northwest path for several days, while environmental conditions allowed for quick intensification. It intensified into Tropical Storm Ike six hours after formation and, on September 3, began a 24-hour period of rapid intensification that saw its winds increase from 85 mph (137 km/h) to a peak of 145 mph (233 km/h). The ridge to Ike's north soon amplified, forcing the hurricane on an unusual, prolonged southwest track while also imparting increased wind shear. After briefly weakening below major hurricane strength, a relaxation in the upper-level winds allowed Ike to reattain Category 4 strength while entering the Turks and Caicos Islands; it then made several landfalls at a slightly reduced intensity. Winds again increased to 130 mph (210 km/h) as Ike moved ashore near Cabo Lucrecia, Cuba. Land interaction prompted structural changes to the storm's core, and Ike only slowly rebounded to an intensity of 110 mph (180 km/h) before its landfall on the northern end of Galveston Island, Texas, early on September 13. Ike curved northeast once inland, interacting with a front the next morning and merging with another low near the Saint Lawrence River on the afternoon of September 15.[32]

In Haiti, Ike compounded the flooding disaster imparted by previous storms Fay, Gustav, and Hanna. The country's food supply, shelter, and transportation networks were ruined. At least 74 deaths were attributed to the hurricane in Haiti, and an additional 2 occurred in the Dominican Republic. In the Turks and Caicos Islands, about 95 percent of all houses on Grand Turk Island were damaged, 20 percent of which severely so. An equal proportion of homes were damaged in South Caicos, including over one-third that were significantly damaged or destroyed. The agricultural and fishing industries suffered significant losses too. The highest concentration of damage in the Bahamas occurred on Inagua, where 70–80 percent of houses sustained roof damage, of which approximately 25 percent saw major damage or were destroyed. Throughout both archipelagos, damage climbed to between $50–200 million.[32] In Cuba, nearly a quarter of the island's population, 2.6 million people, was evacuated in advance of the storm; as a result, only seven deaths were reported. However, structural damage was catastrophic, with 511,259 homes damaged (about 61,202 of which were total losses). About 4,000 metric tons (4,410 st) of foodstuffs were ruined in storage facilities while the island's crops as a whole sustained serious damage.[45] Floodwaters cut off several communities as roads were inundated and bridges were swept away.[32] Ike was estimated to have caused about $7.3 billion in damage across Cuba, making it the costliest hurricane on record there until Hurricane Irma in 2017.[45][89]

While progressing across the Gulf of Mexico, Ike's slow movement and unusually large wind field led to a huge storm surge, upwards of 15–20 ft (4.6–6.1 m), that devastated the Texas coastline. The storm's destruction was most complete on the Bolivar Peninsula, where nearly all homes were wiped off their foundations and demolished. Numerous trees and power lines were downed, cutting power to some 2.6 million customers across Texas and Louisiana. Roads were obstructed by both floodwaters and fallen objects. As Ike transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, it produced extensive wind damage across the Ohio River Valley. In Ohio alone, 2.6 million people lost power. Insured losses climbed to $1.1 billion, comparable to the Xenia tornado of the 1974 Super Outbreak in terms of being the costliest natural disaster in the history of Ohio.[32] Throughout the United States, Ike killed 74 people in Texas,[90] 28 people across the Ohio River Valley,[32] 6 people in Louisiana,[91] and 1 person in Arkansas.[32] Damage reached $30 billion.[33] Farther north in Canada, the remnants of Ike produced record rainfall and high winds across portions of Ontario and Québec.[32]

Tropical Storm Josephine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

A strong tropical wave accompanied by a surface low departed Africa late on August 31. The system began to organize almost immediately after entering the Atlantic, developing into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on September 2 and intensifying into Tropical Storm Josephine six hours later. On a west to west-northwest heading, the cyclone steadily intensified and attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) early on September 3. An exceptionally strong upper-level trough, aided by outflow from nearby Hurricane Ike, prompted a weakening trend thereafter. Despite intermittent bursts of convection, Josephine weakened to a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on September 6 and degenerated to a remnant low six hours later. The low ultimately dissipated on September 10.[92] The storm's remnants impacted Saint Croix early on September 12, producing localized heavy rainfall that flooded roadways.[93]

Hurricane Kyle

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 25 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 984 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa on September 12. The westward-moving feature crossed the Windward Islands on September 19 and began to interact with a strong upper-level trough, leading to an increase in convection and a more evident circulation center. Steering currents directed the disturbance into the southwest Atlantic, where a decrease in wind shear led to the formation of a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on September 25 and organization into Tropical Storm Kyle six hours later. Gradual intensification occurred as the cyclone passed well west of Bermuda; it attained hurricane strength around 12:00 UTC on September 27 and reached peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) a day later. After making landfall just north of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, at 00:00 UTC on September 29, Kyle accelerated northeastward. The storm developed a frontal structure as convection became elongated and asymmetric, leading to its extratropical transition by 06:00 UTC on September 29. A larger extratropical low absorbed it about a day later.[94]

The precursor disturbance to Kyle produced up to 30.47 in (774 mm) of rainfall in Puerto Rico,[50] resulting in numerous flash floods and mudslides that killed six people.[94] About $48 million in damage occurred in Puerto Rico.[95][96] In rain-stricken Haiti, heavy rainfall caused the Orangers River to overflow its banks, resulting in severe damage to homes in Jacmel.[97] In the Northeastern United States, two people were killed by large waves in Rhode Island. Heavy rainfall across Massachusetts and Connecticut led to significant flooding.[98] Kyle produced hurricane-force winds along the southwestern coastline of Nova Scotia that uprooted trees while damaging boats, docks, wharves, and a building under construction.[94] More than 40,000 customers were left without electricity at the height of the storm. Coastal locales were inundated by a combination of storm surge, large waves, and high tides, particularly in Shelburne, where streets were flooded.[58] Kyle and its remnants caused roughly $9 million in damage in Canada.[94]

Tropical Storm Laura

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On September 26, a non-tropical low formed along a quasi-stationary front well west of the Azores. This feature organized into Subtropical Storm Laura by 06:00 UTC on September 29 after shedding its frontal boundaries, and it further developed into a fully tropical system on September 30 as deep convection formed over the center. A northward motion brought the storm over progressively cooler waters on October 1, and it degenerated to a remnant area of low pressure by 12:00 UTC that day. The low merged with a front less than 24 hours later and existed as an extratropical entity until being absorbed by a larger non-tropical low west of the British Isles on October 4.[99] The remnants of Laura produced heavy rainfall on already-saturated ground across the northwestern United Kingdom, overflowing drainage systems and closing roads.[100] In eastern Norway, strong winds downed trees onto roadways and cut power to 10,000 households.[101]

Tropical Storm Marco

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of low pressure persisted across the northwestern Caribbean Sea through the end of September. A tropical wave reached the southwestern Caribbean on October 4, aiding in the formation of a circulation center near Belize. The low tracked across Yucatán Peninsula and, following an increase in convection while over the Laguna de Términos, organized into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on October 6. The newly formed cyclone entered the Bay of Campeche a few hours later and quickly intensified into a tropical storm—the smallest on record in the Atlantic Ocean. Favorable anticyclonic flow aloft aided in continued development of the tightly coiled storm, and Marco attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) early on October 7, an intensity it maintained through landfall east of Misantla around 12:00 UTC that day. Marco's tiny circulation quickly weakened once inland, dissipating by 00:00 UTC on October 8. Impacts from the storm were generally minor,[102] though some low-lying cities were flooded by heavy rainfall.[103]

Tropical Storm Nana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on October 6, accompanied by a broad area of low pressure. The system organized as bands of convection coalesced around the center, leading to the formation of a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on October 12. On a west-northwest course, the depression quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm Nana and attained peak winds of 40 mph (64 km/h). The effects of strong wind shear mitigated further organization, weakening the storm back to tropical depression intensity by 12:00 UTC on October 13 and causing it to degenerate to a remnant low a day later. The low turned northwest and dissipated on October 15.[104]

Hurricane Omar

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 13 – October 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 958 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off Africa on September 30 and failed to organize appreciably until reaching the eastern Caribbean Sea on October 9. There, an increase in convection led to the formation of a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on October 13; it intensified into Tropical Storm Omar eighteen hours later. A broad upper-level trough to the cyclone's northwest caused it to conduct a counter-clockwise turn and accelerate northeast while also aiding in the onset of an extended period of rapid intensification. Omar attained hurricane strength around 00:00 UTC on October 15 before ultimately reaching peak winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) a little over a day later shortly after passing near Saint Croix. Uncharacteristically, the cyclone was plagued by moderate wind shear during its rapid intensification phase, and a further increase in upper-level winds caused Omar to abruptly weaken. The storm continued northeast through the Anegada Passage and into the central Atlantic. Omar weakened to a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on October 18 and degenerating to a remnant low twelve hours later. The low persisted for two days before dissipating.[44]

Omar first impacted the Netherlands Antilles, where large waves caused severe damage to coastal facilities. Winds just shy of tropical storm intensity damaged the roofs of homes and downed several trees. The island of Aruba saw significant flooding from heavy rains. Throughout the United States Virgin Islands, only the eastern sections of Saint Croix received hurricane-force winds, with tropical storm-force winds in surrounding locales. These strong winds nonetheless downed trees and power lines and capsized 94 vessels. Landslides damaged roadways. Overall damage was estimated around $5 million in Saint Croix.[44] Across the Lesser Antilles, the combination of strong winds and frequent lightning caused widespread power outages. Ships were run aground, structures were damaged, and some communities were isolated. Storm surge was severe in western sections of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, causing significant damage to coastal property and businesses.[105] One man died in Puerto Rico after going into cardiac arrest while installing storm shutters.[106] Total damage was estimated at $19 million in Saint Kitts and Nevis,[107] $54 million in Antigua and Barbuda,[108] and $2.6 million in Saint Lucia.[109]

Tropical Depression Sixteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave left Africa on September 27 and moved into the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 10, where a broad area of low pressure formed. The low paralleled the coastline of Nicaragua for a few days while associated convection became better organized; this ultimately led to the development of a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on October 14. The storm maintained a poorly-organized structure throughout its duration, with the low-level center embedded within a larger gyre and little central thunderstorm activity. A reconnaissance aircraft measured peak winds of 30 mph (48 km/h), and the depression maintained these winds as it made landfall just west of Punta Patuca, Honduras, at 12:30 UTC on October 15. It moved west-southwest and ultimately degenerated over mountainous terrain around 06:00 UTC the next day.[47] In mid- to late October, the tropical depression combined with another area of low pressure as well as a cold front to produce torrential rainfall across Central America. In what was described as the region's worst flooding disaster since Hurricane Mitch, crops suffered catastrophic losses, tens of thousands of homes were destroyed, and dozens of people were killed.[110] At least nine deaths were directly attributed to the depression itself.[47]

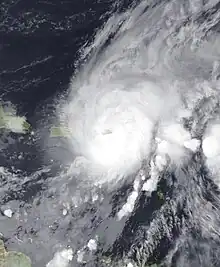

Hurricane Paloma

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 5 – November 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 944 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of disturbed weather developed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on November 1, ultimately coalescing into a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on November 5. It moved north amid a favorable environment, becoming Tropical Storm Paloma twelve hours after formation and attaining hurricane intensity by 00:00 UTC on November 7. An impinging upper-level trough directed Paloma toward the northeast while enhancing outflow, prompting a period of rapid intensification that brought the storm to its peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on November 8, the third strongest November hurricane on record in the Atlantic. An increase in wind shear soon began to take a toll on the cyclone, weakening Paloma to Category 2 strength as it made landfall near Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba, and further to a tropical storm around 06:00 UTC on November 9. It ultimately degenerated to a remnant low early the next day. The low meandered around Cuba before entering the Gulf of Mexico, and it dissipated south of the Florida Panhandle on November 14.[30]

Paloma caused significant impacts on Cayman Brac in the Cayman Islands, where nearly every structure was damaged or destroyed. On nearby Little Cayman, a fewer number of buildings were destroyed while trees and power lines were downed.[30] Damage across the island chain was estimated at $124.5 million.[46] In Cuba, the combination of hurricane-force winds, torrential rainfall, and significant storm surge along the coastline resulted in damage to 12,159 homes; 1,453 of these were destroyed. Hundreds of businesses were impacted, dozens of electrical poles were toppled, and over a dozen bridges were damaged. The island's agricultural sector suffered significant loss. Overall, Paloma inflicted about $300 million in damage there.[45] In Jamaica, rainfall contributed to one death.[111] The storm's remnants moved northward into Florida, resulting in a daily rainfall record in Tallahassee and localized heavy rainfall in surrounding locales.[112]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2008.[113] The names not retired from this list were used again in the 2014 season.[114] This was the same list used in the 2002 season, with the exceptions of Ike and Laura, which replaced Isidore and Lili, respectively.[113] The names Ike, Omar, and Paloma were used for the first (and only, in the cases of Ike and Paloma) time this year. The name Laura was previously used in 1971.[115]

Retirement

On April 22, 2009, at the 31st Session of the RA IV Hurricane Committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the names Gustav, Ike, and Paloma from its rotating name lists due to the number of deaths and damage they caused, and they will not be used again for another Atlantic hurricane. They were replaced with Gonzalo, Isaias, and Paulette for the 2014 season.[114] Isaias and Paulette were not used until the 2020 season.[116]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, intensities, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2008 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur | May 31 – June 2 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | Belize, Yucatán Peninsula, Southwestern Mexico | $78 million | 5 | |||

| Bertha | July 3–20 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 952 | Cabo Verde, Bermuda, East Coast of the United States | Minimal | 3 | |||

| Cristobal | July 19–23 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Southeastern United States, Atlantic Canada | $10,000 | None | |||

| Dolly | July 20–25 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 963 | Guatemala, Yucatán Peninsula, Northeastern Mexico, South Central United States | $1.6 billion | 26 | |||

| Edouard | August 3–6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 996 | Gulf Coast of the United States | $800,000 | 6 | |||

| Fay | August 15–27 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 986 | Leeward Islands, Greater Antilles, Southeastern United States | $560 million | 33 | |||

| Gustav | August 25 – September 4 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 941 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Gulf Coast of the United States, Midwestern United States | $8.31 billion | 161 | |||

| Hanna | August 28 – September 7 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 977 | Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Hispaniola, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | $160 million | 533 | |||

| Ike | September 1–14 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 935 | Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, Cuba, Gulf Coast of the United States, Midwestern United States, Eastern Canada, Iceland | $38 billion | 192 | |||

| Josephine | September 2–6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | Cabo Verde, Leeward Islands | Minimal | None | |||

| Kyle | September 25–29 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 984 | Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Bermuda, New England, The Maritimes | $57.1 million | 8 | |||

| Laura | September 29 – October 1 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 994 | British Isles, Netherlands, Norway | Minimal | None | |||

| Marco | October 6–7 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Eastern Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Nana | October 12–14 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Omar | October 13–18 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 958 | Lesser Antilles, Venezuela, Puerto Rico | $44.6 million | 1 | |||

| Sixteen | October 14–15 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1004 | Honduras, Belize | ≥ $150 million | 9 | |||

| Paloma | November 5–10 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 944 | Nicaragua, Honduras, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Cuba, The Bahamas, Florida | $454.5 million | 1 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 17 systems | May 30 – November 10 | 155 (250) | 935 | ≥ 48.855 billion | 1,074[nb 3] | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2008

- 2008 Pacific hurricane season

- 2008 Pacific typhoon season

- 2008 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

Footnotes

- All damage figures are in 2008 USD, unless otherwise noted

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- The number of deaths in the table do not add up to 1,074. This is because Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike combined caused 793 fatalities in Haiti,[31] but the highest confirmed totals for each storm in Haiti are 10 from Fay, 85 from Gustav, 529 from Hanna,[34] and 74 from Ike.[32]

References

- Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (December 7, 2007). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2008" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- "Background information: the North Atlantic hurricane season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 8, 2006. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- William M. Gray; Phillip J. Klotzbach (August 5, 2008). Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity, August Monthly Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2008 (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Carmeyia Gillis (August 7, 2008). "Strong Start Increases NOAA's Confidence for Above-Normal Atlantic Hurricane Season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Mark Saunders; Dr. Adam Lea (August 5, 2008). August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2008 (PDF) (Report). London, England: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "WSI Stands by 'Active' Hurricane Season Forecast". Natural Gas Intelligence. August 27, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Christopher W. Landsea (2019). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Mark Saunders; Dr. Adam Lea (December 10, 2007). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2008 (PDF) (Report). London, England: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "Seven Atlantic Hurricanes This Year, WSI Says". Natural Gas Intelligence. January 3, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- William M. Gray; Phillip J. Klotzbach (April 9, 2008). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2008 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Mark Saunders; Dr. Adam Lea (April 7, 2008). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2008 (PDF) (Report). London, England: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "WSI Adds Another Intense Hurricane to Tropical Forecast". Natural Gas Intelligence. April 23, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Carmeyia Gillis; David Miller (May 22, 2008). NOAA Predicts Near Normal or Above Normal Atlantic Hurricane Season (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- William M. Gray; Phillip J. Klotzbach (June 3, 2008). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2008 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mark Saunders; Dr. Adam Lea (June 5, 2008). June Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2008 (PDF) (Report). London, England: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2008". Met Office. June 18, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "WSI Still Sees 'Active' Hurricane Season Ahead". Natural Gas Intelligence. July 2, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "WSI Ups Forecast: Nine Hurricanes This Year". Natural Gas Intelligence. July 23, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Mark Saunders; Dr. Adam Lea (July 4, 2008). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2008 (PDF) (Report). London, England: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "2008 Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Rainfall". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Eric S. Blake (July 28, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arthur (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (Report). National Hurricane Center. December 1, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Daniel P. Brown, John L. Beven, James L. Franklin, and Eric S. Blake (May 2010). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2008". Monthly Weather Review. 138 (5): 1975. Bibcode:2010MWRv..138.1975B. doi:10.1175/2009MWR3174.1. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jeff Masters (November 26, 2008). "Hurricane season of 2008 draws to a close". Weather Underground. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Hurricanes and Tropical Storms - Annual 2008 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. January 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Major May–June–July Hurricanes". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- "Late Season Major Hurricanes". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Michael J. Brennan (January 26, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Paloma (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Haiti: Hurricane Season 2008 (PDF) (Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. October 19, 2010. p. 3. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Robbie J. Berg (January 23, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ike (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- "Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Dr. Debarati Guha-Sapir (January 28, 2010). Disasters in Numbers 2009 and the Decade (PDF). Emergency Events Database (Report). Centre for Research on Epidemiology of Disasters. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- North Carolina Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Pennsylvania Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Daniel P. Brown; Todd B. Kimberlain (December 17, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Hanna (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- John L. Beven II; Todd B. Kimberlain (January 22, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Gustav (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Adam Smith, Neal Lott, Tamara Houston, Karsten Shein, Jake Crouch, Jesse Enloe. U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather & Climate Disasters 1980-2019 (PDF) (Report). National Climatic Data Center. p. 9. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Demian McLean (July 23, 2008). "Dolly Makes Landfall in Texas; Downgraded to Storm (Update3)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Jamie R. Rhome (October 15, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Bertha (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

-

- Eric S. Blake (July 28, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arthur (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- New Jersey Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- Demian McLean (July 23, 2008). "Dolly Makes Landfall in Texas; Downgraded to Storm (Update3)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Adam Smith, Neal Lott, Tamara Houston, Karsten Shein, Jake Crouch, Jesse Enloe. U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather & Climate Disasters 1980-2019 (PDF) (Report). National Climatic Data Center. p. 9. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Global Hazards - July 2008 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Hallan muerto a pescador extraviado en Yucatán tras paso de Dolly". La Jornada (in Spanish). July 24, 2008. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Richard J. Pasch; Todd B. Kimberlain (January 22, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Dolly (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Mobile, Alabama. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Alabama Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Mobile, Alabama. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- James L. Franklin (November 14, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Edouard (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Dr. Debarati Guha-Sapir (January 28, 2010). Disasters in Numbers 2009 and the Decade (PDF). Emergency Events Database (Report). Centre for Research on Epidemiology of Disasters. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Killer storm Fay may become hurricane before hitting Florida". ABC News. August 18, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Jim Ash (September 9, 2008). "Central, South Fla. brace for Ike's rain". Florida Today. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Boy Drowns in Cairo: Funeral Set". WCTV News. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Brendan Kirby (August 25, 2008). "Death blamed on Fay". AL.com. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Tropical Storm Gustav OCHA Situation Report No. 3 (Report). ReliefWeb. August 30, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- John L. Beven II; Todd B. Kimberlain (January 22, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Gustav (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Government of Cuba (April 2009). Review of the Past Hurricane Season: Reports of Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tropical Disturbances and Related Flooding during 2008 (DOC) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- "Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- North Carolina Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- North Carolina Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Pennsylvania Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Daniel P. Brown; Todd B. Kimberlain (December 17, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Hanna (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- Robbie J. Berg (January 23, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ike (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- David F. Zane; et al. (March 2011). "Tracking Deaths Related to Hurricane Ike, Texas, 2008". Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. Cambridge University Press. 5 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1001/dmp.2011.8. PMID 21402823. S2CID 34372746.

- "7:43 a.m.: Hurricane Ike deaths, state by state". The Herald Bulletin. Associated Press. September 15, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Lixion A. Avila (December 5, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Kyle (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Storm Events Database". National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Event Details: Flash Flood (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Event Details: High Surf (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Norton, Massachusetts. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Jack L. Beven II; Christopher W. Landsea (February 3, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Omar (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Government of Saint Lucia (April 2009). Review of the Past Hurricane Season: Reports of Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tropical Disturbances and Related Flooding during 2008 (DOC) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Daniel P. Brown (November 19, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Sixteen (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Government of Jamaica (2008). Jamaica's Report on the 2008 Hurricane Season (Report). Caribbean Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- Macro Socio-Economic Assessment of the Damage and Losses Caused by Hurricane Paloma (PDF) (Report). United Nations. April 2, 2009. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- "NASA reports 2008 is ninth warmest year since 1880". Great Falls Tribune. McClatchy-Tribune News Service. December 17, 2008. p. 5A. Retrieved February 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jack L. Beven II; Christopher W. Landsea (February 3, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Omar (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Government of Cuba (April 2009). Review of the Past Hurricane Season: Reports of Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tropical Disturbances and Related Flooding during 2008 (DOC) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Macro Socio-Economic Assessment of the Damage and Losses Caused by Hurricane Paloma (PDF) (Report). United Nations. April 2, 2009. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- Daniel P. Brown (November 19, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Sixteen (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- "Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Bertha speeds away from Bermuda". Reuters. July 15, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- Roth, David M (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - New Jersey Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- Delaware Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- North Carolina Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- Lixion A. Avila (December 15, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Cristobal (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Bill Bair (July 18, 2008). "System Likely to Deliver More Rain to Polk". The Ledger. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Flash Flood (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Miami, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- "Tropical Storm Cristobal weakens along N.C. coast". USA Today. July 20, 2008. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Canada. Review of the Past Hurricane Season: Reports of Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tropical Disturbances and Related Flooding during 2008 (DOC) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Richard J. Pasch; Todd B. Kimberlain (January 22, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Dolly (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- Global Hazards - July 2008 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Adriana Varillas (July 23, 2008). "Tormenta 'Dolly' se llevó la arena de playas de Cancún". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- "Dos muertos y tres desaparecidos en México por el paso de "Dolly"". Última Hora (in Spanish). July 24, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Roberto Aguilar Grimaldo (July 24, 2008). "Reportan un muerto por Dolly en Matamoros". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- "Un deceso en Juárez por los remanentes de Dolly". La Jornada (in Spanish). July 29, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Alicia Caldwell (July 28, 2008). "Body found in debris from N.M. flash flooding". Fox News. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- "Hurricane Dolly remnants bring downpour to El Paso". USA Today. July 26, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- James L. Franklin (November 14, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Edouard (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tallahassee, Florida. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Florida Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Mobile, Alabama. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Alabama Event Report: Rip Current (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Mobile, Alabama. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Louisiana Event Report: Tropical Storm (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Lake Charles, Louisiana. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Texas Event Report: Tropical Storm (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Lake Charles, Louisiana. 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Storm Events Database". National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Storm Events Database". National Centers for Environmental Information. 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Stacy R. Stewart; John L. Beven II (February 8, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Fay (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Killer storm Fay may become hurricane before hitting Florida". ABC News. August 18, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Satta Sarmah (November 30, 2008). "Fay led unrelenting barrage of storms". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Tropical Storm Fay floods hundreds of homes". NBC News. August 20, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Jim Ash (September 9, 2008). "Central, South Fla. brace for Ike's rain". Florida Today. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Boy Drowns in Cairo: Funeral Set". WCTV News. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Brendan Kirby (August 25, 2008). "Death blamed on Fay". AL.com. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Tropical Storm Gustav OCHA Situation Report No. 3 (Report). ReliefWeb. August 30, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Haiti: IOM aids hurricane Gustav victims (Report). ReliefWeb. September 2, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Jeff Masters (January 27, 2010). "A new world record wind gust: 253 mph in Australia's Tropical Cyclone Olivia". Weather Underground. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Ben Lundin; Matthew Pleasant; Robert Zullo (September 1, 2008). "Picture begins to emerge of Gustav's damage". The Houma Courier. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- South Carolina Event Report: Heavy Rain (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Cuba: Hurricane Irma - Revised Emergency appeal (MDRCU004) (Report). ReliefWeb. June 5, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- David F. Zane; et al. (March 2011). "Tracking Deaths Related to Hurricane Ike, Texas, 2008". Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. Cambridge University Press. 5 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1001/dmp.2011.8. PMID 21402823. S2CID 34372746.

- "7:43 a.m.: Hurricane Ike deaths, state by state". The Herald Bulletin. Associated Press. September 15, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Eric S. Blake (December 5, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Josephine (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Puerto Rico Event Report: Heavy Rain (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Lixion A. Avila (December 5, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Kyle (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Storm Events Database". National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Event Details: Flash Flood (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Caribbean Hurricane Season OCHA Situation Report No. 18 (Report). ReliefWeb. September 25, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2019.