U.S. territorial sovereignty

In the United States, a territory is any extent of region under the sovereign jurisdiction of the federal government of the United States,[1] including all waters (around islands or continental tracts). The United States asserts sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing its territory.[2] This extent of territory is all the area belonging to, and under the dominion of, the United States federal government (which includes tracts lying at a distance from the country) for administrative and other purposes.[1] The United States total territory includes a subset of political divisions.

Territory of the United States

The United States' territory includes any geography under the control of the United States federal government. Various regions, districts, and divisions are under the supervision of the United States federal government. The United States' territory includes clearly defined geographical area and refers to an area of land, air, or sea under jurisdiction of United States federal governmental authority (but is not limited only to these areas). The extent of territory is all the area belonging to, and under the dominion of, the United States of America federal government (which includes tracts lying at a distance from the country) for administrative and other purposes.

Constitution of the United States

Under Article IV of the U.S. Constitution, a territory is subject to and belongs to the United States (but not necessarily within the national boundaries or any individual state). This includes tracts of land or water not included within the limits of any State and not admitted as a State into the Union.

The Constitution of the United States states:

The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

Congress of the United States

Congress possesses power to set territorial governments within the boundaries of the United States, under Article 4, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. The first exercise of this power was the Northwest Ordinance of 1789. The power of Congress over such territory is exclusive and universal, including the creation of political divisions, except as delegated to a territory's government by act of Congress.

Supreme Court of the United States

All territory under the control of the federal government is considered part of the "United States" for purposes of law.[3] From 1901 to 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court in a series of opinions known as the Insular Cases held that the Constitution extended ex proprio vigore to the territories. However, the Court in these cases also established the doctrine of territorial incorporation. Under the same, the Constitution only applied fully in incorporated territories such as Alaska and Hawaii, whereas it only applied partially in the new unincorporated territories of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.[4][5] A Supreme Court ruling from 1945 stated that the term "United States" can have three different meanings, in different contexts:

The term "United States" may be used in any one of several senses. It may be merely the name of a sovereign occupying the position analogous to that of other sovereigns in the family of nations. It may designate the territory over which the sovereignty of the United States extends, or it may be the collective name of the states which are united by and under the Constitution.

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior is charged with managing federal affairs within U.S. territory.[6] The Interior Department has a wide range of responsibilities (which include the regulation of territorial governments and the basic stewardship for public lands, et al.). The United States Department of the Interior is not responsible for local government or for civil administration except in the cases of Indian reservations, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, as well as those territories administered through the Office of Insular Affairs. The exception is the "incorporated and unorganized" (see below) United States Territory of Palmyra Island, the legal remnant of the former United States Territory of Hawaii since 1959,[7] in which the local government and civil administration were assigned by the Secretary of the Interior to the Fish and Wildlife Service in 2001.[8]

United States divisions

States, territories, and their subdivisions

The contiguous United States, Hawaii, and Alaska are divided into smaller administrative regions. These are called counties in 48 of the 50 states, boroughs in Alaska and parishes in Louisiana. A county can include a number of cities and towns, or just a portion of either type. These counties have varying degrees of political and legal significance. A township in the United States refers to a small geographic area. The term is used in two ways: a survey township is simply a geographic reference used to define property location for deeds and grants; a civil township is a unit of local government, originally rural in application.

The District of Columbia and territories are under the direct authority of Congress, although each is allowed home rule.[9] The United States government, rather than individual states or territories, conducts foreign relations under the U.S. Constitution.

Federal enclaves, such as domestic military bases and national parks, are administered directly by the federal government. To varying degrees, the federal government exercises concurrent jurisdiction with the states where federal land is part of the territory previously granted to a state.

History of United States territory

At times, territories are organized with a separate legislature, under a territorial governor and officers, appointed by the President and approved by the Senate of the United States. A territory has been historically divided into organized territories and unorganized territories.[10][11] An unorganized territory was generally either unpopulated or set aside for Native Americans and other indigenous peoples in the United States by the U.S. federal government, until such time as the growing and restless population encroached into the areas. In recent times, "unorganized" refers to the degree of self-governmental authority exercised by the territory.

As a result of several Supreme Court cases after the Spanish–American War, the United States had to determine how to deal with its newly acquired territories, such as the Philippines,[12][13] Puerto Rico,[14] Guam,[15][16] Wake Island, and other areas that were not part of the North American continent and which were not necessarily intended to become a part of the Union of States. As a consequence of the Supreme Court decisions, the United States has since made a distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories.[17][18][19] In essence, an incorporated territory is land that has been irrevocably incorporated within the sovereignty of the United States and to which the full corpus of the U.S. Constitution applies. An unincorporated territory is land held by the United States, and to which Congress of the United States applies selected parts of the constitution. At the present time, the only incorporated U.S. territory is the unorganized (and unpopulated) Palmyra Atoll.

State land claims and cessions to the federal government (1782–1802)

State land claims and cessions to the federal government (1782–1802) Admission of states and territorial acquisition, U.S. Bureau of the Census

Admission of states and territorial acquisition, U.S. Bureau of the Census Territorial acquisitions of the United States

Territorial acquisitions of the United States States and incorporated territories of the United States, August 21, 1959, to present

States and incorporated territories of the United States, August 21, 1959, to present

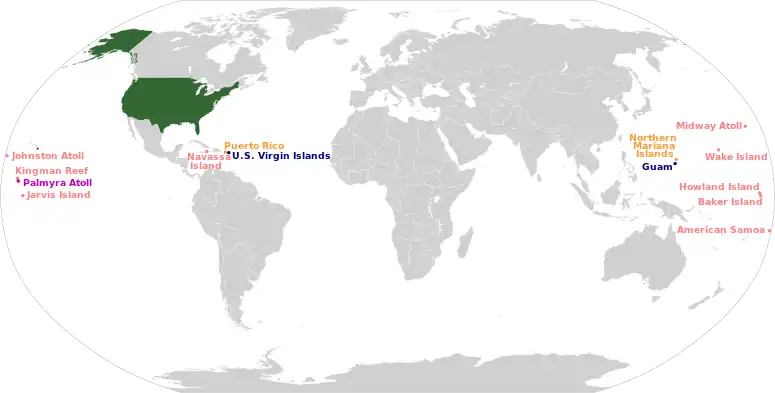

Insular areas

The United States currently claims 16 insular areas as territories:

- American Samoa

- Guam

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Puerto Rico

- United States Virgin Islands

- Minor Outlying Islands

- The italicized islands are part of a territory dispute with Colombia and are not included in the ISO designation of the USMOI. The United States does not administer these two territories.

Palmyra Atoll is the only incorporated territory remaining, and having no government it is also unorganized. The remaining are unincorporated territories of the United States. Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands are styled as commonwealths.

Dependent areas

Several islands in the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea are dependent territories of the United States.[20][21]

The Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, notionally under the sovereignty of Cuba, is administered by the United States under a perpetual lease, much as the Panama Canal Zone used to be before the signing of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. Only mutual agreement or U.S. abandonment of the area can terminate the lease.

From July 8, 1947, until October 1, 1994, the United States administered the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, but the Trust ceased to exist when the last member state of Palau gained its independence to become the Republic of Palau. The Panama canal, and the Canal Zone surrounding it, was territory administered by the United States until 1999, when control was relinquished to Panama.

The United States has made no territorial claim in Antarctica but has reserved the right to do so. American research stations in Antarctica—Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, McMurdo Station, and Palmer Station—are under U.S. jurisdiction but are held without sovereignty per the Antarctic Treaty.

The three Freely Associated States of Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau are not under U.S. sovereignty, but each participates in federal programs under a Compact of Free Association.

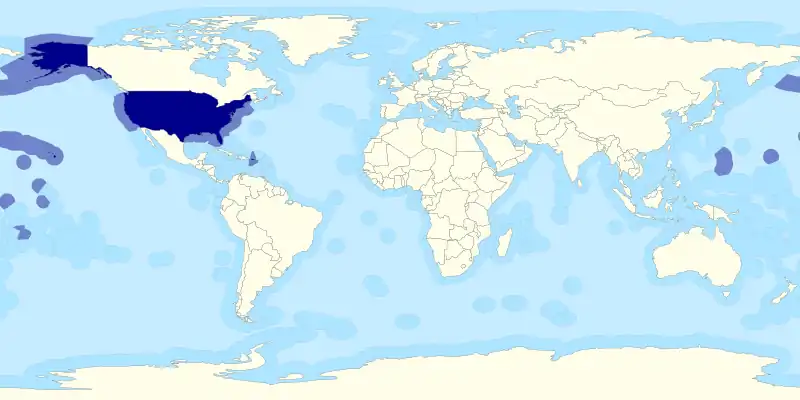

Maritime territory of the United States

The government of the United States of America has claims to the oceans in accord with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which delineates a zone of territory adjacent to territorial lands and seas. United States protects this marine environment, though not interfering with other lawful uses of this zone. The United States' jurisdiction has been established on vessels, ships, and artificial islands (along with other marine structures).

In 1983 President Ronald Reagan, through Proclamation No. 5030, claimed a 200-mile exclusive economic zone. In December 1988, President Reagan, through Proclamation No. 5928, extended U.S. territorial waters from three nautical miles to twelve nautical miles for national security purposes. However a legal opinion from the Justice Department questioned the President's constitutional authority to extend sovereignty as Congress has the power to make laws concerning the territory belonging to the United States under the U.S. Constitution. In any event, Congress needs to make laws defining if the extended waters, including oil and mineral rights, are under state or federal control.[22][23]

The primary enforcer of maritime law is the U.S. Coast Guard. Federal and state governments share economic and regulatory jurisdiction over the waters owned by the country. (See tidelands.)

International law

The United States is not restricted from making laws governing its own territory by international law. United States territory can include occupied territory, which is a geographic area that claims sovereignty, but is being forcibly subjugated to the authority of the United States of America. United States territory can also include disputed territory, which is a geographic area claimed by the United States of America and one (or more) rival governments.

Under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, United States territory can include areas occupied by and controlled by the United States Armed Forces. When de facto military control is maintained and exercised, occupation (and thus possession) extends to that territory. Military personnel in control of the territory have a responsibility to provide for the basic needs of individuals under their control (which includes food, clothing, shelter, medical attention, law maintenance, and social order). To prevent systematic abuse of puppet governments by the occupation forces, they must enforce laws that were in place in the territory prior to the occupation.

Customs territories

The fifty states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico form the main customs territory of the United States. Special rules apply to foreign trade zones in these areas. Separate customs territories are formed by American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Other areas

U.S. sovereignty includes the airspace over its land and territorial waters. No international agreement exists on the vertical limit that separates this from outer space, which is international.

Federal jurisdiction includes federal enclaves like national parks and domestic military bases, even though these are located in the territory of a state. Host states exercise concurrent jurisdiction to some degree.

The United States exercises extraterritoriality on military installations, American embassies and consulates located in foreign countries, and research centers and field camps in Antarctica. Despite exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction, these overseas locations remain under the sovereignty of the host countries (except Antarctica, where there is no host country). Because they are not part of any state, extraterritorial jurisdiction is federal, with Congress's plenary power under Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution.

The federal government also exercises property ownership, but not sovereignty over land in various foreign countries. Examples include the John F. Kennedy Memorial built at Runnymede in England,[24] and 32 acres (13 hectares) around Pointe du Hoc in Normandy, France.[25][26][27]

History of U.S. federal lands

The Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided for the survey and settlement of the lands that the original Thirteen Colonies ceded to the federal government after the American Revolution.[28] As additional lands were acquired by the United States from Spain, France and other countries, the United States Congress directed that they be explored, surveyed, and made available for settlement.[28] During the Revolutionary War, military bounty land was promised to soldiers who fought for the colonies.[29] After the war, the Treaty of Paris of 1783, signed by the United States, the UK, France, and Spain, ceded territory to the United States.[30][31] In the 1780s, other states relinquished their own claims to land in modern-day Ohio.[32] By this time, the United States needed revenue to function.[33] Land was sold so that the government would have money to survive.[33] In order to sell the land, surveys needed to be conducted. The Land Ordinance of 1785 instructed a geographer to oversee this work as undertaken by a group of surveyors.[33] The first years of surveying were completed by trial and error; once the territory of Ohio had been surveyed, a modern public land survey system had been developed.[34] In 1812, Congress established the General Land Office as part of the Department of the Treasury to oversee the disposition of these federal lands.[32] By the early 1800s, promised bounty land claims were finally fulfilled.[35]

In the 19th century, other bounty land and homestead laws were enacted to dispose of federal land.[28][35] Several different types of patents existed.[36] These include cash entry, credit, homestead, Indian, military warrants, mineral certificates, private land claims, railroads, state selections, swamps, town sites, and town lots.[36] A system of local land offices spread throughout the territories, patenting land that was surveyed via the corresponding Office of the Surveyor General of a particular territory.[36] This pattern gradually spread across the entire United States.[34] The laws that spurred this system with the exception of the General Mining Law of 1872 and the Desert Land Act of 1877 have since been repealed or superseded.[37]

In the early 20th century, Congress took additional steps toward recognizing the value of the assets on public lands and directed the Executive Branch to manage activities on the remaining public lands.[37] The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 allowed leasing, exploration, and production of selected commodities, such as coal, oil, gas, and sodium to take place on public lands.[38] The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 established the United States Grazing Service to manage the public rangelands by establishment of advisory boards that set grazing fees.[39][40] The Oregon and California Revested Lands Sustained Yield Management Act of 1937, commonly referred as the O&C Act, required sustained yield management of the timberlands in western Oregon.[41]

Currently, federal lands are about 640 million acres, about 28% of the total U.S. land area of 2.27 billion acres.[42][43]

See also

References

- Hurd, John C. (1968) [1858]. The Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United States. New York: Negro Universities Press. pp. 438–439. OCLC 10955.

- Smith, Robert W. (1986). Exclusive Economic Zone Claims: An Analysis and Primary Documents. Hingham, Mass.: M. Nijhoff. p. 467. ISBN 90-247-3250-6. OCLC 424143523.

- See 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(36) and 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(38) Providing the term "State" and "United States" definitions on the U.S. Federal Code, Immigration and Nationality Act. 8 U.S.C. § 1101a

- CONSEJO DE SALUD PLAYA DE PONCE v JOHNNY RULLAN, SECRETARY OF HEALTH OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO Page 6 and 7 (PDF), The United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico, archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2011, retrieved February 4, 2010.

- The Insular Cases: The Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid" (2007) Juan R. Torruella (PDF), retrieved February 5, 2010.

- Towle, Nathaniel C. (1861). A History and Analysis of the Constitution of the United States. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 384–385. OCLC 60723860.

- "GAO/OGC-98-5 – U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution; Appendix II:0.3, footnote 22". U.S. Government Printing Office. November 7, 1997. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- Secretary of the Interior Order No. 3224, January 18, 2001.

- "District of Columbia Home Rule Act". abfa.com. November 19, 1997. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- Berg-Andersson, Richard E. (July 14, 2008). "Official Name and Status History of the several States and U.S. Territories". The Green Papers. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- "Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 1784–1894". The Library of Congress. 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- "Philippines – United States Rule". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- "Philippines – A Collaborative Philippine Leadership". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- "Treaty of Paris (1898)". Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- Paul Carano and Pedro C. Sanchez, A Complete History of Guam (Rutland, VT: C. E. Tuttle, 1964)

- Howard P. Willens and Dirk Ballendorf, The Secret Guam Study: How President Ford's 1975 Approval of Commonwealth Was Blocked by Federal Officials (Mangilao, Guam: Micronesian Area Research Center; Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historical Preservation, 2004)

- FindLaw: Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901) regarding the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories

- FindLaw: People of Puerto Rico v. Shell Co., 302 U.S. 253 (1937) regarding application of U.S. law to organized but unincorporated territories

- FindLaw: United States v. Standard Oil Company, 404 U.S. 558 (1972) regarding application of U.S. law to unorganized unincorporated territories

- "Office of Insular Affairs". Archived from the original on June 17, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- Department of the Interior Definitions of Insular Area Political Types Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Andrew Rosenthal (December 29, 1988). "Reagan Extends Territorial Waters to 12 Miles". New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- Carol Elizabeth Remy (1992). "U.S. Territorial Sea Extension: Jurisdiction and International Environmental Protection". Fordham International Law Journal. 16 (4): 1208–1252. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- Evans, D. M. Emrys (1965). "John F. Kennedy Memorial Act, 1964". The Modern Law Review. 28 (6): 703–706.

- "The American Battle Monuments Commission". Retrieved October 29, 2012.

The site, preserved since the war by the French Committee of the Pointe du Hoc, which erected an impressive granite monument at the edge of the cliff, was transferred to American control by formal agreement between the two governments on 11 January 1979 in Paris, with Ambassador Arthur A. Hartman signing for the United States and Secretary of State for Veterans Affairs Maurice Plantier signing for France.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The American Battle Monuments Commission".

- "The BLM: The Agency and its History". GPO. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- "Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files (p. 7)" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration (1974). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- "British-American Diplomacy Treaty of Paris – Hunter Miller's Notes". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Black, Jeremy. British foreign policy in an age of revolutions, 1783–1793 (1994) pp 11–20

- A History of the Rectangular Survey System by C. Albert White, 1983, Pub: Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management: For sale by G.P.O.

- Vernon Carstensen, "Patterns on the American Land." Journal of Federalism, Fall 1987, Vol. 18 Issue 4, pp 31–39

- White, C. Albert (1991). A history of the rectangular survey system. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- "Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files (p. 3)" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration (1974). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- "Records of the Bureau of Land Management [BLM] (Record Group 49) 1685–1993 (bulk 1770–1982)". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- "BLM and Its Predecessors: A Long and Varied History". BLM. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- "Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 As Amended" (PDF). BLM. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- Wishart, David J. (ed.). "Taylor Grazing Act". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- Elliott, Clayton R. (August 2010). Innovation in the U.S. Bureau of Land Management: Insights from Integrating Mule Deer Management with Oil and Gas Leasing (Masters Thesis) (Thesis). University of Montana. p. 45. hdl:2027.42/77588.

- "O&C Sustained Yield Act: the Law, the Land, the Legacy" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Lipton, Eric, and Clifford Krauss, Giving Reins to the States Over Drilling, New York Times, August 24, 2012.

- Carol Hardy Vincent, Carla N. Argueta, & Laura A. Hanson, Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data, Congress Research Service (March 3, 2017).

Notes

- Fleury Graff, Thibaut (2013). Etat et territoire en droit international. L'exemple de la construction du territoire des Etats-Unis (1789–1914) (State and Territory in International Law. The case of United States' Territory (1789–1914)). Paris, France: Pedone. ISBN 978-2-233-00686-8.

- Lalor, John J. (1899). "Territories". Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States. New York: Maynard, Merrill, and Co. OCLC 221087006.

- McFerson, Hazel M. (1997). The Racial Dimension of American Overseas Colonial Policy. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28996-4. OCLC 36301430.

- Willoughby, Westel W. (1910). The Constitutional Law of the United States. Vol. 2. New York: Baker, Voorhis & Company. OCLC 180533376.