1884 United States presidential election

The 1884 United States presidential election was the 25th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 1884. In the election, Governor Grover Cleveland of New York defeated Republican James G. Blaine of Maine. It was set apart by unpleasant mudslinging and shameful personal allegations that eclipsed substantive issues, such as civil administration change. Cleveland was the first Democrat elected President of the United States since James Buchanan in 1856, the first to hold office since Andrew Johnson left the White House in 1869, and the last to hold office until Woodrow Wilson, who began his first term in 1913. For this reason, 1884 is a significant election in U.S. political history, marking an interruption in the era when Republicans largely controlled the presidency between Reconstruction and the Great Depression.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

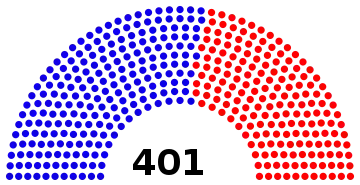

401 members of the Electoral College 201 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 77.5%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

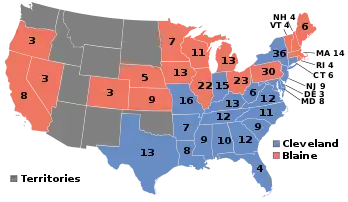

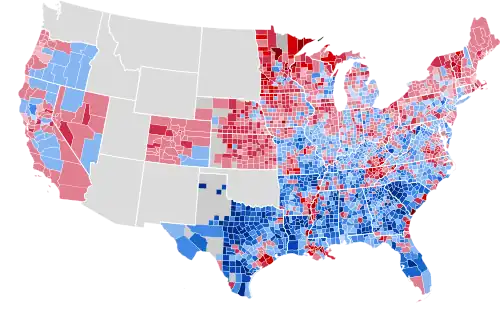

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes those won by Cleveland/Hendricks, red denotes states won by Blaine/Logan. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cleveland won the presidential nomination on the second ballot of the 1884 Democratic National Convention. President Chester A. Arthur had acceded to the presidency in 1881 following the assassination of James A. Garfield, but he was unsuccessful in his bid for nomination to a full term. Blaine, who had served as Secretary of State under President Garfield, defeated Arthur and other candidates on the fourth ballot of the 1884 Republican National Convention. A group of reformist Republicans known as "Mugwumps" abandoned Blaine's candidacy, viewing him as corrupt. The campaign was marred by exceptional political acrimony and personal invective. Blaine's reputation for public corruption and his inadvertent last-minute alienation of Catholic voters proved decisive.

In the election, Cleveland won 48.9% of the nationwide popular vote and 219 electoral votes, carrying the Solid South and several key swing states. Blaine won 48.3% of the popular vote and 182 electoral votes. Cleveland won his home state by just 1,149 votes; had he lost New York, he would have lost the election. Two third-party candidates, John St. John of the Prohibition Party and Benjamin Butler of the Greenback Party and the Anti-Monopoly Party, each won less than 2% of the popular vote. Blaine was the last former Secretary of State to be nominated by a major political party until the nomination of Hillary Clinton in 2016, while Cleveland became the only sitting Democratic president between the end of the civil war and the election of Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 United States presidential election, a span of almost 50 years. Blaine, similarly, also became the only Republican nominee in the 60-year period between 1856 and 1916 to never win a presidential election, and just one of two nominees from that party to never win the presidency in the 80-year span between 1856 and 1936.

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic Party (United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grover Cleveland | Thomas A. Hendricks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28th Governor of New York (1883–1885) |

16th Governor of Indiana (1873–1877) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Democrats convened in Chicago on July 8–11, 1884, with New York Governor Grover Cleveland as clear frontrunner, the candidate of northern reformers and sound-money men (as opposed to inflationists). Although Tammany Hall bitterly opposed his nomination, the machine represented a minority of the New York delegation. Its only chance to block Cleveland was to break the unit rule, which mandated that the votes of an entire delegation be cast for only one candidate, and this it failed to do. Daniel N. Lockwood from New York placed Cleveland's name in nomination. But this rather lackluster address was eclipsed by the seconding speech of Edward S. Bragg from Wisconsin, who roused the delegates with a memorable slap at Tammany. "They love him, gentlemen," Bragg said of Cleveland, "and they respect him, not only for himself, for his character, for his integrity and judgment and iron will, but they love him most of all for the enemies he has made." As the convention rocked with cheers, Tammany boss John Kelly lunged at the platform, screaming that he welcomed the compliment.

On the first ballot, Cleveland led the field with 392 votes, more than 150 votes short of the nomination. Trailing him were Thomas F. Bayard from Delaware, 170; Allen G. Thurman from Ohio, 88; Samuel J. Randall from Pennsylvania, 78; and Joseph E. McDonald from Indiana, 56; with the rest scattered. Randall then withdrew in Cleveland's favor. This move, together with the Southern bloc scrambling aboard the Cleveland bandwagon, was enough to put him over the top of the second ballot, with 683 votes to 81.5 for Bayard and 45.5 for Thomas A. Hendricks from Indiana. Hendricks was nominated unanimously for vice president on the first ballot after John C. Black, William Rosecrans, and George Washington Glick withdrew their names from consideration.[2]

Republican Party nomination

Republican Party (United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James G. Blaine | John A. Logan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28th U.S. Secretary of State (1881) |

U.S. Senator from Illinois (1871–1877 & 1879–1886) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1884 Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, Illinois, on June 3–6, with former Secretary of State James G. Blaine from Maine, President Arthur, and Senator George F. Edmunds from Vermont as the frontrunners. Though he was still popular, Arthur did not make a serious bid for a full-term nomination, knowing that his increasing health problems meant he would probably not survive a second term (he ultimately died in November 1886). Blaine led on the first ballot, with Arthur second, and Edmunds third. This order did not change on successive ballots as Blaine increased his lead, and he won a majority on the fourth ballot. After nominating Blaine, the convention chose Senator John A. Logan from Illinois as the vice-presidential nominee. Blaine remains the only Presidential nominee ever to come from Maine.[3]

Famed Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman was considered a possible Republican candidate, but ruled himself out with what has become known as the Sherman pledge: "If drafted, I will not run; if nominated, I will not accept; if elected, I will not serve." Robert Todd Lincoln, Secretary of War of the United States, and son of the past President Abraham Lincoln, was also strongly courted by politicians and the media of the day to seek the presidential or vice-presidential nomination, but Lincoln was as averse to the nomination as Sherman.

Anti-Monopoly Party nomination

Anti-Monopoly candidates:

Allen G. Thurman from Ohio

Allen G. Thurman from Ohio.jpg.webp)

The Anti-Monopoly National Convention assembled in the Hershey Music Hall in Chicago, Illinois on May 14.[4] The party had been formed to express opposition to the business practices of the emerging nationwide companies. There were around 200 delegates from 16 states, but 61 of them were from Michigan and Illinois.

Alson Streeter was the temporary chairman and John F. Henry was the permanent chairman.

Benjamin F. Butler was nominated for president on the first ballot. Delegates from New York, Washington, D.C., and Maryland bolted the convention when it appeared that no discussion of other candidates would be allowed. Allen G. Thurman and James B. Weaver were put forward as alternatives to Butler, but Weaver declined, not wishing to run another national campaign for political office, and Thurman generated little enthusiasm. Butler, while far from opposed to the nomination, hoped to be nominated by the Democratic or Republican party, or at least in the case of the former, to make its platform more favorable to greenbacks. Ultimately only the Greenback Party endorsed his candidacy.

The convention chose not to nominate a candidate for vice president, hoping that other conventions would endorse a similar platform and name a suitable vice-presidential nominee.[5]: 55 The committee ultimately nominated Absolom Madden West as their vice-presidential candidate.[6]: 56

| Presidential Ballot[6]: 56 | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| Benjamin F. Butler | 124 |

| Allen G. Thurman[lower-alpha 1] | 2 |

| Solon Chase | 1 |

Greenback Party nomination

Greenback candidates:

The 3rd Greenback Party National Convention assembled in English's Opera House in Indianapolis, Indiana. Delegates from 28 states and the District of Columbia attended. The convention nominated Benjamin F. Butler for president over its Party Chairman Jesse Harper on the first ballot. Absolom M. West was nominated unanimously for vice president, and subsequently was also endorsed by the Anti-Monopoly Party.

Butler had initially hoped to form a number of fusion slates with the "minority party" in each state, Democratic or Republican, and for his supporters of various parties to come together under a single "People's Party". But many in the two major parties, while maybe agreeing with Butler's message and platform, were unwilling to place their support beyond the party line. In a number of places, Iowa in particular, fusion slates were nominated; essentially, Butler's and Cleveland's votes would be added together for the total vote of the fusion slate, allowing them to carry the state even if neither won a plurality, with the electoral vote being divided according to the percentage of the vote each party netted.[7]

But even if Fusion had been carried out in every state in which it was considered possible (Indiana, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Illinois), it would not have changed the result, none of the states flipping from Blaine to Cleveland, with Butler winning a single electoral vote from Indiana.

| Presidential Ballot[6]: 57 | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| Benjamin F. Butler | 323 |

| Jesse Harper | 98 |

| Solon Chase | 2 |

| Edward Phelps Allis | 1 |

| David Davis | 0 |

American Prohibition Party nomination

The American Prohibition Party held its national convention in the YMCA building in Chicago, Illinois. There were 150 delegates, including many non-voting delegates. The party sought to merge the reform movements of anti-masonry, prohibition, anti-polygamy, and direct election of the president into a new party. Jonathan Blanchard was a major figure within the party. He traveled throughout northern states in the spring and gave an address entitled "The American Party – Its Principles and Its Claims."

During the convention, the party name was changed from the American Party to the American Prohibition Party. The party had been known as the Anti-Masonic Party in 1880. Many of the delegates at the convention were initially interested in nominating John St. John, the former governor of Kansas, but it was feared that such a nomination might cost him that of the Prohibition Party, which he was actively seeking. Party leaders met with Samuel C. Pomeroy, a former senator from the same state who was the convention's runner-up for the nomination, and at Pomeroy's suggestion they agreed to withdraw the ticket from the race should St. John win the Prohibition Party nomination. Nominated alongside Pomeroy was John A. Conant from Connecticut.

St. John later unanimously won the Prohibition Party nomination, with Pomeroy and Conant withdrawing from the presidential contest and endorsing him. The New York Times speculated that the endorsement would "give him 40,000 votes".[8]

Prohibition Party nomination

John St. John from Kansas

John St. John from Kansas

The fourth Prohibition Party National Convention assembled in Lafayette Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There were 505 delegates from 31 states and territories at the convention. The national ticket was nominated unanimously: John St. John for president and William Daniel for vice president. The straightforward single-issue Prohibition Party platform advocated the criminalization of alcoholic beverages.[6]: 58

| Presidential Ballot[5]: 56 | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| John St. John | 505 |

Equal Rights Party nomination

Dissatisfied with resistance by the men of the major parties to women's suffrage, a small group of women announced the formation in 1884 of the Equal Rights Party.

The Equal Rights Party held its national convention in San Francisco, California, on September 20. The convention nominated Belva Ann Lockwood, an attorney in Washington, D.C., for president. Chairman Marietta Stow, the first woman to preside over a national nominating convention, was nominated for vice president.[6]: 57 [5]: 56

Lockwood agreed to be the party's presidential candidate even though most women in the United States did not yet have the right to vote. She said, "I cannot vote but I can be voted for." She was the first woman to run a full campaign for the office (Victoria Woodhull conducted a more limited campaign in 1872). The Equal Rights Party had no treasury, but Lockwood gave lectures to pay for campaign travel. She received approximately 4,194 votes nationally.[9]

General election

Campaign

The issue of personal character was paramount in the 1884 campaign. Blaine had been prevented from getting the Republican presidential nomination during the previous two elections because of the stigma of the "Mulligan letters": in 1876, a Boston bookkeeper named James Mulligan had located some letters showing that Blaine had sold his influence in Congress to various businesses. One such letter ended with the phrase "burn this letter", from which a popular chant of the Democrats arose – "Burn, burn, burn this letter!" In just one deal, he had received $110,150 (over $1.5 million in 2010 dollars) from the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad for securing a federal land grant, among other things. Democrats and anti-Blaine Republicans made unrestrained attacks on his integrity as a result. Cleveland, on the other hand, was known as "Grover the Good" for his personal integrity; in the space of the three previous years he had become successively the mayor of Buffalo, New York, and then the governor of the state of New York, cleaning up large amounts of Tammany Hall's graft.

Commentator Jeff Jacoby notes that, "Not since George Washington had a candidate for president been so renowned for his rectitude."[10] In July the Republicans found a refutation buried in Cleveland's past. Aided by sermons from a minister named George H. Ball, they charged that Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child while he was a lawyer in Buffalo. When confronted with the scandal, Cleveland immediately instructed his supporters to "Above all, tell the truth." Cleveland admitted to paying child support in 1874 to Maria Crofts Halpin, the woman who claimed he fathered her child, named Oscar Folsom Cleveland after Cleveland's friend and law partner, but asserted that the child's paternity was uncertain.[11] Shortly before election day, the Republican media published an affidavit from Halpin in which she stated that until she met Cleveland her "life was pure and spotless," and "there is not, and never was, a doubt as to the paternity of our child, and the attempt of Grover Cleveland, or his friends, to couple the name of Oscar Folsom, or any one else, with that boy, for that purpose is simply infamous and false."[12] In a supplemental affidavit, Halpin also implied Cleveland had raped her, hence the conception of their child.[12][13] Republican cartoonists across the land had a field day.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

Cleveland's campaign decided that candor was the best approach to this scandal: it admitted that Cleveland had formed an "illicit connection" with the mother and that a child had been born and given the Cleveland surname. They also noted that there was no proof that Cleveland was the father, and claimed that, by assuming responsibility and finding a home for the child, he was merely doing his duty. Finally, they showed that the mother had not been forced into an asylum; her whereabouts were unknown. Blaine's supporters condemned Cleveland in the strongest of terms, singing "Ma, Ma, Where's my Pa?"[20] (After Cleveland's victory, Cleveland supporters would respond to the taunt with: "Gone to the White House, Ha, Ha, Ha.") However, the Cleveland campaign's damage control worked well enough and the race remained a tossup through Election Day. The greatest threat to the Republicans came from reformers called "Mugwumps" who were angrier at Blaine's public corruption than at Cleveland's private affairs.[21]

In the final week of the campaign, the Blaine campaign suffered a catastrophe. At a Republican meeting attended by Blaine, a group of New York preachers castigated the Mugwumps. Their spokesman, Reverend Dr. Samuel Burchard, said, "We are Republicans, and don't propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism, and rebellion." Blaine did not notice Burchard's anti-Catholic slur, nor did the assembled newspaper reporters, but a Democratic operative did, and Cleveland's campaign managers made sure it was widely publicized. The statement energized the Irish and Catholic vote in New York City heavily against Blaine, costing him New York state and the election by a narrow margin.

In addition to Burchard's statement, it is also believed that John St. John's campaign was responsible for winning Cleveland the election in New York. Since Prohibitionists tended to ally more with Republicans, the Republican Party attempted to convince St. John to drop out. When they failed, they resorted to slandering him. Because of this, he redoubled his efforts in upstate New York, where Blaine was vulnerable on his prohibition stance, and took votes away from the Republicans.[22]

Results

While the results remained broadly the same as those from 1880, Cleveland won three states (New York, Indiana, and Connecticut) that James A. Garfield had won, while Blaine won two states (California and Nevada) that Winfield Hancock had won. But most of those states had relatively small numbers of electoral votes, and Cleveland's victory in New York was decisive. Cleveland won by a slightly larger margin than Garfield (0.57% compared to 0.11%) in the popular vote, but a slightly smaller margin in the Electoral College (29 votes to 59). Cleveland became the first Democrat to ever win without Pennsylvania, California, Nevada, and Illinois. Pennsylvania voted for the losing candidate for the first time since 1824, and the loser of the popular vote since 1800.

The result marked an electoral breakthrough for the Prohibition Party, who had been little more than a fringe party in the previous three elections. While they never seriously challenged for the presidency and had only limited success in congressional and state-level elections, they regularly earned at least a percentage point of the popular vote (and occasionally finished third in that vote) in presidential elections for the next three decades before declining back to fringe status after the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. By contrast, Butler earned less than half the popular vote share that James B. Weaver had won in 1880, accelerating the decline of the Greenback Party. This was the last presidential election the party contested; it collapsed after failing to nominate a ticket in 1888.

In Burke County, Georgia, 897 votes were cast for bolting "Whig Republican" electors for president (they were not counted for Blaine).[23] The Republicans won in 20 of the 33 cities with populations over 50,000 outside the southern U.S.[24]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Stephen Grover Cleveland | Democratic | New York | 4,914,482 | 48.85% | 219 | Thomas Andrews Hendricks | Indiana | 219 |

| James Gillespie Blaine | Republican | Maine | 4,856,903 | 48.28% | 182 | John Alexander Logan | Illinois | 182 |

| John Pierce St. John | Prohibition | Kansas | 147,482 | 1.50% | 0 | William Daniel | Maryland | 0 |

| Benjamin Franklin Butler | Greenback/Anti-Monopoly | Massachusetts | 134,294 | 1.33% | 0 | Absolom Madden West | Mississippi | 0 |

| Belva Ann Bennett Lockwood | Equal Rights | Washington, D.C. | 4,194 | 0.04% | 0 | Marietta L.B. Stow | California | 0 |

| Other | 3,576 | 0.04% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 10,060,145 | 100% | 401 | 401 | ||||

| Needed to win | 201 | 201 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1884 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Geography of results

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Map of presidential election results by county

Map of presidential election results by county Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Map of Republican presidential election results by county Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.[25]

| States/districts won by Cleveland/Hendricks |

| States/districts won by Blaine/Logan |

| Grover Cleveland Democratic |

James Blaine Republican |

John St. John Prohibition |

Benjamin Butler Greenback |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 10 | 92,736 | 60.37 | 10 | 59,444 | 38.69 | – | 610 | 0.40 | – | 762 | 0.50 | – | 33,292 | 21.67 | 153,624 | AL |

| Arkansas | 7 | 72,734 | 57.83 | 7 | 51,198 | 40.70 | – | – | – | – | 1,847 | 1.47 | – | 21,536 | 17.12 | 125,779 | AR |

| California | 8 | 89,288 | 45.33 | – | 102,369 | 51.97 | 8 | 2,965 | 1.51 | – | 2,037 | 1.03 | – | −13,081 | −6.64 | 196,988 | CA |

| Colorado | 3 | 27,723 | 41.68 | – | 36,084 | 54.25 | 3 | 756 | 1.14 | – | 1,956 | 2.94 | – | −8,361 | −12.57 | 66,519 | CO |

| Connecticut | 6 | 67,182 | 48.95 | 6 | 65,898 | 48.01 | – | 2,493 | 1.82 | – | 1,684 | 1.23 | – | 1,284 | 0.94 | 137,257 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 16,957 | 56.55 | 3 | 12,953 | 43.20 | – | 64 | 0.21 | – | 10 | 0.03 | – | 4,004 | 13.35 | 29,984 | DE |

| Florida | 4 | 31,769 | 52.96 | 4 | 28,031 | 46.73 | – | 72 | 0.12 | – | – | – | – | 3,738 | 6.23 | 59,990 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 94,667 | 65.92 | 12 | 48,603 | 33.84 | – | 195 | 0.14 | – | 145 | 0.10 | – | 46,064 | 32.08 | 143,610 | GA |

| Illinois | 22 | 312,351 | 46.43 | – | 337,469 | 50.17 | 22 | 12,074 | 1.79 | – | 10,776 | 1.60 | – | −25,118 | −3.73 | 672,670 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 245,005 | 49.46 | 15 | 238,489 | 48.15 | – | 3,028 | 0.61 | – | 8,810 | 1.78 | – | 6,516 | 1.32 | 495,332 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 177,316 | 47.01 | – | 197,089 | 52.25 | 13 | 1,499 | 0.40 | – | – | – | – | −19,773 | −5.24 | 377,201 | IA |

| Kansas | 9 | 90,132 | 33.90 | – | 154,406 | 58.08 | 9 | 4,495 | 1.69 | – | 16,346 | 6.15 | – | −64,274 | −24.18 | 265,848 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 152,961 | 55.32 | 13 | 118,690 | 42.93 | – | 3,139 | 1.14 | – | 1,691 | 0.61 | – | 34,271 | 12.40 | 276,481 | KY |

| Louisiana | 8 | 62,594 | 57.22 | 8 | 46,347 | 42.37 | – | 338 | 0.31 | – | 120 | 0.11 | – | 16,247 | 14.85 | 109,399 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 52,153 | 39.97 | – | 72,217 | 55.34 | 6 | 2,160 | 1.66 | – | 3,955 | 3.03 | – | −20,064 | −15.38 | 130,491 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 96,866 | 52.07 | 8 | 85,748 | 46.10 | – | 2,827 | 1.52 | – | 578 | 0.31 | – | 11,118 | 5.98 | 186,019 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 122,352 | 40.33 | – | 146,724 | 48.36 | 14 | 9,923 | 3.27 | – | 24,382 | 8.04 | – | −24,372 | −8.03 | 303,383 | MA |

| Michigan | 13 | 189,361 | 47.20 | – | 192,669 | 48.02 | 13 | 18,403 | 4.59 | – | 753 | 0.19 | – | −3,308 | −0.82 | 401,186 | MI |

| Minnesota | 7 | 70,065 | 36.87 | – | 111,685 | 58.78 | 7 | 4,684 | 2.47 | – | 3,583 | 1.89 | – | −41,620 | −21.90 | 190,017 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 77,653 | 64.34 | 9 | 43,035 | 35.66 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 34,618 | 28.68 | 120,688 | MS |

| Missouri | 16 | 236,023 | 53.49 | 16 | 203,081 | 46.02 | – | 2,164 | 0.49 | – | – | – | – | 32,942 | 7.47 | 441,268 | MO |

| Nebraska | 5 | 54,391 | 40.53 | – | 76,912 | 57.31 | 5 | 2,899 | 2.16 | – | – | – | – | −22,521 | −16.78 | 134,202 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 5,578 | 43.59 | – | 7,193 | 56.21 | 3 | – | – | – | 26 | 0.20 | – | −1,615 | −12.62 | 12,797 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 39,198 | 46.34 | – | 43,254 | 51.14 | 4 | 1,580 | 1.87 | – | 554 | 0.65 | – | −4,056 | −4.80 | 84,586 | NH |

| New Jersey | 9 | 127,798 | 48.98 | 9 | 123,440 | 47.31 | – | 6,159 | 2.36 | – | 3,496 | 1.34 | – | 4,358 | 1.67 | 260,921 | NJ |

| New York | 36 | 563,154 | 48.25 | 36 | 562,005 | 48.15 | – | 25,006 | 2.14 | – | 17,004 | 1.46 | – | 1,149 | 0.10 | 1,167,169 | NY |

| North Carolina | 11 | 142,905 | 53.25 | 11 | 125,021 | 46.59 | – | 430 | 0.16 | – | – | – | – | 17,884 | 6.66 | 268,356 | NC |

| Ohio | 23 | 368,280 | 46.94 | – | 400,082 | 50.99 | 23 | 11,069 | 1.41 | – | 5,179 | 0.66 | – | −31,802 | −4.05 | 784,610 | OH |

| Oregon | 3 | 24,604 | 46.70 | – | 26,860 | 50.99 | 3 | 492 | 0.93 | – | 726 | 1.38 | – | −2,256 | −4.28 | 52,682 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 30 | 392,785 | 43.46 | – | 478,804 | 52.97 | 30 | 15,283 | 1.69 | – | 16,992 | 1.88 | – | −86,019 | −9.52 | 903,864 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 12,391 | 37.81 | – | 19,030 | 58.07 | 4 | 928 | 2.83 | – | 422 | 1.29 | – | −6,639 | −20.26 | 32,771 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 69,845 | 75.25 | 9 | 21,730 | 23.41 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 48,115 | 51.84 | 92,812 | SC |

| Tennessee | 12 | 133,770 | 51.45 | 12 | 124,101 | 47.74 | – | 1,150 | 0.44 | – | 957 | 0.37 | – | 9,669 | 3.72 | 259,978 | TN |

| Texas | 13 | 225,309 | 69.26 | 13 | 93,141 | 28.63 | – | 3,534 | 1.09 | – | 3,321 | 1.02 | – | 132,168 | 40.63 | 325,305 | TX |

| Vermont | 4 | 17,331 | 29.18 | – | 39,514 | 66.52 | 4 | 1,753 | 2.95 | – | 785 | 1.32 | – | −22,183 | −37.34 | 59,401 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 145,491 | 51.05 | 12 | 139,356 | 48.90 | – | 130 | 0.05 | – | – | – | – | 6,135 | 2.15 | 284,977 | VA |

| West Virginia | 6 | 67,311 | 50.94 | 6 | 63,096 | 47.75 | – | 939 | 0.71 | – | 799 | 0.60 | – | 4,215 | 3.19 | 132,145 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 11 | 146,453 | 45.79 | – | 161,135 | 50.38 | 11 | 7,649 | 2.39 | – | 4,598 | 1.44 | – | −14,682 | −4.59 | 319,835 | WI |

| TOTALS: | 401 | 4,914,482 | 48.85 | 219 | 4,856,903 | 48.28 | 182 | 150,890 | 1.50 | – | 134,294 | 1.33 | – | 57,579 | 0.57 | 10,060,145 | US |

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (55 electoral votes):

- New York, 0.10% (1,149 votes) (tipping point state)

- Michigan, 0.82% (3,308 votes)

- Connecticut, 0.94% (1,284 votes)

Margin of victory between 1% and 5% (117 electoral votes):

- Indiana, 1.32% (6,516 votes)

- New Jersey, 1.67% (4,358 votes)

- Virginia, 2.15% (6,135 votes)

- West Virginia, 3.19% (4,215 votes)

- Tennessee, 3.72% (9,669 votes)

- Illinois, 3.73% (25,118 votes)

- Ohio, 4.05% (31,802 votes)

- Oregon, 4.28% (2,256 votes)

- Wisconsin, 4.59% (14,682 votes)

- New Hampshire, 4.80% (4,056 votes)

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (104 electoral votes):

- Iowa, 5.24% (19,773 votes)

- Maryland, 5.98% (11,118 votes)

- Florida, 6.23% (3,738 votes)

- California, 6.64% (13,081 votes)

- North Carolina, 6.66% (17,884 votes)

- Missouri, 7.47% (32,942 votes)

- Massachusetts, 8.03% (24,372 votes)

- Pennsylvania, 9.52% (86,019 votes)

See also

Notes

- Published sources disagree on how many votes Thurman received on the ballot. Hinshaw claims he received 7 votes, but Havel finds only 2.

References

- "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- William DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, Gramercy 1997

- ‘What States do Presidents Come From?’

- "Today in labor history:Anti-Monopoly Party founded". People's World. May 14, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- Hinshaw, Seth (2000). Ohio Elects the President: Our State's Role in Presidential Elections 1804-1996. Mansfield: Book Masters, Inc.

- Havel, James T. (1996). U.S. Presidential Elections and the Candidates: A Biographical and Historical Guide. Vol. 2: The Elections, 1789–1992. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-864623-1.

- "FUSION AND CONFUSION. - View Article - NYTimes.com" (PDF). New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- "WITHDRAWS IN FAVOR OF ST. JOHN. - View Article - NYTimes.com" (PDF). New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- Soden, Suzanne. Belva A. Lockwood Collection [1830–1917]. The College of Saint Rose. February, 1997. http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/msscfa/sc21041.htm

- Jeff Jacoby, "'Grover the good' — the most honest president of them all," Boston Globe Feb. 15. 2015

- Henry F. Graff (2002). Grover Cleveland: The American Presidents Series: The 22nd and 24th President, 1885–1889 and 1893–1897. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 61–63. ISBN 9780805069235.

- Lachman, Charles (2014). A Secret Life. Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 285–288.

- Bushong, William; Chervinsky, Lindsay (2007). "The Life and Presidency of Grover Cleveland". White House History.

- Glen Jeansonne, "Caricature and Satire in the Presidential Campaign of 1884." Journal of American Culture (1980) 3#2 pp: 238–244. Online

- "Maria Halpin's Affidavit" (PDF). Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY). October 31, 1884. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Daily Gazette (Fort Wayne, Indiana) Nov. 1, 1884. p. 5

- Topeka Daily Capital (Topeka, Kansas) Nov. 1, 1884. p. 4

- "That Scandal". Wichita Daily Eagle (Wichita, Kansas). November 2, 1884. p. 2. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, (Cedar Rapids, Iowa). October 31, 1884. p. 3

- Tugwell, 90

- Geoffrey T. Blodgett, "The Mind of the Boston Mugwump." Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1962): 614–634. in JSTOR

- "HarpWeek | Elections | 1884 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- An American Almanac and Treasury of Facts, Statistical, Financial, and Political, for the year 1886., Ainsworth R. Spofford, https://books.google.com/books?id=1ZcYAAAAIAAJ (pg. 207)

- Murphy, Paul (1974). Political Parties In American History, Volume 3, 1890-present. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- "1884 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved May 7, 2013.

Sources

- Davies, Gareth; Zelizer, Julian E, eds. (2015). America at the Ballot Box. doi:10.9783/9780812291360. ISBN 9780812291360.

- Hirsch, Mark. "Election of 1884," in History of Presidential Elections: Volume III 1848–1896, ed. Arthur Schlesinger and Fred Israel (1971), 3:1578.

- Josephson, Matthew (1938). The Politicos: 1865–1896.

- Keller, Morton (1977). Affairs of State: Public Life in Late Nineteenth Century America. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674181885. ISBN 9780674181885.

- Kleppner, Paul (1979). The Third Electoral System 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures.

- Lynch, G. Patrick (2002). "U.S. Presidential Elections in the Nineteenth Century: Why Culture and the Economy Both Mattered". Polity. 35: 29–50. doi:10.1086/POLv35n1ms3235469. S2CID 157740436.

- Norgren, Jill. Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would be President (2007). online version, focus on 1884

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1969). From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896.

- James Ford Rhodes (1920). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Roosevelt-Taft Administration (8 vols.).

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren. Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion: The Making of a President, 1884 (2000) online version

- "1884 Election Cleveland v. Blaine Overview", HarpWeek, July 26, 2008.

- Roberts, North (2004). Encyclopedia of Presidential Campaigns, Slogans, Issues, and Platforms.

- Thomas, Harrison Cook, The return of the Democratic Party to power in 1884 (1919) online

Primary sources

- The Republican Campaign Text Book for 1884. Republican Congressional Committee. 1882.

Democratic campaign text Book.

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

- Presidential Election of 1884: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1884 popular vote by counties

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Election of 1884 in Counting the Votes Archived May 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine