Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern Confederacy. The United States Army considers it the first of the American Indian Wars.[1]

| Northwest Indian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

This depiction of the Treaty of Greenville negotiations may have been painted by one of Anthony Wayne's officers. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Chickasaw Choctaw |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Blue Jacket Little Turtle Buckongahelas Egushawa | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,221 killed 458 wounded |

1,000+ killed Unknown wounded | ||||||||

Following centuries of conflict for control of this region, the land comprising the Northwest Territory was granted to the new United States by the Kingdom of Great Britain in article 2 of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War. The treaty used the Great Lakes as a border between British territory and the United States. This granted significant territory to the United States, initially known as the Ohio Country and the Illinois Country, which had previously been prohibited to new settlements. However, numerous Native American peoples inhabited this region, and the British maintained a military presence and continued policies that supported their Native allies. With the encroachment of European-American settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains after the war, a Huron-led confederacy formed in 1785 to resist the usurpation of Indian lands, declaring that lands north and west of the Ohio River were Indian territory.

Four years after the start of the British-supported Native American military campaign, the Constitution of the United States went into effect; George Washington was sworn in as president, which made him the commander-in-chief of U.S. military forces. Accordingly, Washington directed the United States Army to enforce U.S. sovereignty over the territory. The U.S. Army, consisting mostly of untrained recruits and volunteer militiamen, suffered a series of major defeats, including the Harmar campaign (1790) and St. Clair's defeat (1791), which are among the worst defeats ever suffered in the history of the U.S. Army.

St. Clair's devastating loss destroyed most of the United States Army and left the United States vulnerable. Washington was also under congressional investigation and was compelled to quickly raise a bigger army. He chose Revolutionary War veteran General Anthony Wayne to organize and train a proper fighting force. Wayne took command of the new Legion of the United States late in 1792 and spent a year building, training, and acquiring supplies. After a methodical campaign up the Great Miami and Maumee river valleys in western Ohio Country, Wayne led his Legion to a decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near the southwestern shore of Lake Erie (near modern Toledo, Ohio) in 1794. Afterward, he went on to establish Fort Wayne at the Miami capital of Kekionga, the symbol of U.S. sovereignty in the heart of Indian Country and within sight of the British. The defeated tribes were forced to cede extensive territory, including much of present-day Ohio, in the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The Jay Treaty in the same year arranged for cessions of British Great Lakes outposts on the U.S. territory. The British would later retake this land briefly during the War of 1812.

Background

In the French and Indian War (1754–1760), France and Great Britain fought for control of the region south of the Great Lakes known as the Ohio and Illinois countries. Indigenous tribes of the region fought on both sides of the conflict, aligning themselves with the imperial power best suited to their economic and political needs. In the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the war, France ceded the region to the British. That year, a confederation of Natives launched Pontiac's War, an effort to drive the British away. Seeking to avoid further hostilities, the British issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, creating a boundary line between colonists and Native lands.[2]

In 1768, British officials negotiated the Treaty of Fort Stanwix with the Iroquois, who claimed sovereignty over the Ohio Country. The treaty moved the boundary line further west and opened up territory south of the Ohio River to colonial settlement. While colonial elites like George Washington organized land companies and secured grants, immigrants began pouring into the region.[3] Natives (primarily Shawnees and Cherokees) who used present-day Kentucky as their hunting grounds had not been consulted in the treaty and denied that the Iroquois had the right to sell the land.[4][5] In the early 1770s, the Shawnees worked to create a new Native confederacy to resist colonial occupation, but British officials successfully used the Iroquois to isolate them.[6] As a result, the Shawnees fought and lost Lord Dunmore's War in 1774 with only a few Mingo allies, and they were compelled to assent to the Ohio River boundary between the colonies and Native lands.[7][8]

To better control the frontier, in 1774 the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act, which placed the entire region under the jurisdiction of the Province of Quebec, nullifying colonial land claims.[9][10] American colonists who hoped to own or settle these lands were outraged, contributing to their decision to declare independence from Britain in 1776.[11][12] Many Natives allied with the British in the western theater of the American Revolutionary War, seeking to drive out American settlers. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the war, Great Britain ceded the region to the United States, making no mention of Native land rights.[13] The Native nations technically remained at war with the United States, and Richard Butler argued to them that the British had "cast you off, and given us your country."[14]

Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, who had fought in the Revolution as a British ally, was stunned to learn that "England had sold the Indians to Congress."[15] In 1783 he took the lead in forming the Northwestern Confederacy, the "most ambitious pan-tribal confederacy yet."[16] At the Wyandot town of Junquindundeh (modern Fremont, Ohio), Brant argued that Native lands were held in common by all tribes and so no land could be ceded without the consent of the confederacy.[17] Among the attendees at the conference were representatives from the Iroquois, Shawnees, Delawares (Lenapes), Wyandots, Three Fires (Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi), as well as a few Cherokees and Creeks.[16]

In the following years, U.S. states relinquished their claims in the region to the federal government, which intended to pay debts from the Revolution by selling lands north of the Ohio River to American settlers.[18] American officials refused to recognize the Native confederacy and instead pursued a policy of divide and rule. They informed the Natives their lands had been taken by right of conquest and sought to confirm this in a series of treaties in which the Americans dictated the terms.[19][20] Some Native leaders buckled to the pressure and ceded land at Fort Stanwix (1784), Fort McIntosh (1785), and Fort Finney (1786). Hardline and militant Natives remained committed to defending their lands north of the Ohio River. Shawnees and Lenapes sent out messages calling for war.[21]

Course of the war

After a number of raids and counter-raids along the Ohio River boundary, in 1786 the Kentucky militia launched the first major frontier military action since the end of the Revolutionary War.[22] Generals George Rogers Clark and Benjamin Logan headed a two-pronged invasion of Native land. In September, Clark led 1,200 militiamen north along the Wabash River. Beset by logistical problems, mutiny, and desertion, Clark turned back without accomplishing anything.[23] In October, Logan led 790 Kentucky militiamen to the Shawnee towns along the Mad River. The towns were inhabited primarily by noncombatants because the warriors had scattered for the winter hunt. Logan's men burned the towns and food supplies, killing and capturing numerous Natives. Moluntha, an elderly Shawnee chief who had signed the Fort Finney treaty, was executed by one of Logan's men.[24][25]

After the destruction of their towns, Shawnee refugees were invited by the Miamis to settle along the Wabash. The towns around Kekionga, the Miami capital, were now inhabited by many of the most militant members of the Northwestern Confederacy.[26] The next meeting of the confederacy had been scheduled to be held in the Shawnee towns, but with their destruction the location was moved to the Wyandot village of Brownstown on the Detroit River. Joseph Brant spoke to a gathering that included Miamis and other members of the Wabash Confederacy.[27] On December 18, 1786, the confederacy, calling themselves the "United Indian Nations," sent a letter to the U.S. Confederation Congress declaring the recent treaties invalid because they had not been conducted with the whole confederacy. They called for a new treaty conference to be held in the spring of 1787. Until that time, the Natives suggested that each party should keep its people on their side of the Ohio River.[27]

In July 1787, the U.S. Confederation Congress created the Northwest Territory north of the Ohio River in preparation of widespread, organized American settlement of the region.[28] Arthur St. Clair, appointed as territorial governor, moved to Marietta, the first American settlement north of the river. He was instructed to negotiate new treaties without surrendering any lands ceded in previous treaties, acquire more land if possible, and work to undermine the Native confederacy.[29][30] In 1788, St. Clair invited Natives to Fort Harmar near Marietta, instead of a neutral site preferred by the Natives.[31] Brant sent St. Clair a message asking if he would accept a new boundary, preserving everything west of the Muskingum River as Native land. When St. Clair dismissed the idea, Brant boycotted the negotiations and suggested others do the same. The Northwestern Confederacy was deeply divided. Those living closest to the Americans supported compromise. Those further away – the Miamis, Lenapes and Shawnees around Kekionga – insisted upon the Ohio River boundary.[32] In January 1789, a group of mostly minor chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Harmar, which merely confirmed the terms of the previous, disputed treaties. "I am persuaded their general confederacy is entirely broken," wrote St. Clair.[33] Instead of breaking the confederacy, St. Clair had discredited Natives willing to compromise and strengthened the influence of the militants.[34]

After the Fort Harmar treaty, violence between Natives and settlers escalated. Natives attacked flatboats on the Ohio River and raided into Kentucky, killing, capturing, and torturing settlers in an attempt to stem the tide of immigrants.[35] Americans responded with counter raids, such as one led by Major John Hardin, who in August 1789 led 220 Kentucky militiamen to the Wabash region, where they killed eight Shawnees, including women and children.[36] In 1790, George Washington, recently inaugurated as the first President of the United States, and Secretary of War Henry Knox decided to attack the Native confederacy to secure the Northwest Territory for American occupation.[37] Because many Americans distrusted the idea of a professional "standing army," Congress kept the United States Army small and relied upon state-run militias for defense.[38] In 1790, Congress expanded the army's single regiment, the First American Regiment, from 700 to 1,216 men.[39] For the duration of the war, the Americans would use combined operations of militiamen and regulars, with a U.S. Army officer in overall command.[40]

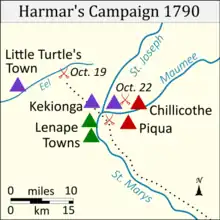

1790: Harmar campaign

On 20 April 1790, the First American Regiment participated in its first offensive against Native Americans when General Josiah Harmar joined Kentucky General Charles Scott in an attack on the Shawnee village of Chalawgatha. The next month, Native Americans retaliated by attacking settlers near Limestone (modern-day Maysville, Kentucky) in a skirmish known as Hartshorne's Defeat, leaving 5 settlers dead and 8 missing.[41] That autumn, the United States launched a major offensive against the Natives along the Maumee River. This punitive expedition was led by General Harmar, whose orders were to destroy Kekionga and the surrounding towns, killing any Natives who opposed him.[42] His army, consisting of 1,100 militiamen and 320 regulars, departed Fort Washington on the Ohio River on September 30.[43] A diversionary force led by Major Jean François Hamtramck invaded from Vincennes, though it turned back before joining with Harmar.[44]

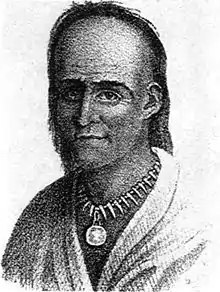

Native scouts monitored the slow progress of Harmar's northward march. The Natives had scattered for their annual winter hunt, but Blue Jacket, the principal Shawnee war chief, and Little Turtle, his Miami counterpart, dispatched messengers calling for the warriors to regroup.[45] They managed to collect about 600 men to oppose Harmar's army.[46] This was not enough men to face the largest army most of them had ever seen,[43] so they evacuated the noncombatants from the towns on October 14[47] and watched for an opportunity to strike.[48] Harmar's advance detachment under John Hardin reached Kekionga on October 15 and spent the next few days looting and burning Native towns, as well as destroying the crops.[47] On October 19, Hardin led 180 men on a reconnaissance mission to discover a Native war party thought to be nearby. About 16 miles from Kekionga, Hardin's scattered men were ambushed and routed by about 150 Shawnee and Potawatomi warriors.[49][50] Soon after, the Natives received additional reinforcements of Odawas, Sacs, and Foxes.[51]

On October 21, Harmar declared that his objective—the destruction of the towns—had been fulfilled, and so the army would return to Fort Washington.[52] The expedition had destroyed five Miami towns and 20,000 bushels of their corn.[53] They marched south, but the following day, Harmar agreed to allow a detachment of 400 men to return to Kekionga and attack any Natives who might reoccupy the town. This raid was led by Major John P. Wyllys, a regular army officer, with Hardin serving under him and commanding the militia. As they approached Kekionga, Wyllys divided his men, hoping to surround and trap the Natives.[54] Instead, the Natives again ambushed the Americans and defeated them piecemeal, the survivors barely managing to regroup with Harmar's army.[55][56] Blue Jacket and Little Turtle hoped to strike again at Harmar's retreating army, but a lunar eclipse the following night was regarded by many Natives as an ill omen, and the attack was called off.[57][58]

Blue Jacket, disappointed with the lost opportunity, headed for Detroit where he sought British help in opposing the next, inevitable American invasion.[59] "We now, Father, call for your assistance," he said.[60] The British commander at Detroit was noncommittal. When Blue Jacket's request was relayed to Guy Carleton (Lord Dorchester), the Governor General of British North America, he replied, "We are at peace with the United States and wish to remain so."[60] By remaining neutral in the conflict, the British confirmed they no longer regarded the Natives in the Northwest Territory as allies to be supported in wartime.[61]

Harmar's expedition had ended in defeat, with a total of 183 killed and missing.[58][62] The Miamis on the other hand had lost nearly a tenth of their military manpower.[53] Harmar's military career was over, his campaign regarded as a "national embarrassment" that needed to be avenged.[62] "The general impression upon the result of the late expedition," Knox wrote to Harmar, "is that it has been unsuccessful; that it will not induce the Indians to peace, but on the contrary encourage them to a continuance of hostilities, and that, therefore, another and more efficient expedition must be undertaken."[63]

1791: St. Clair's defeat

After Harmar's campaign, Natives rebuilt their villages around Kekionga, although some relocated to other locations. Natives did not typically go to war in winter, but they followed up their victory over Harmar with raids on American settlements north of the Ohio River.[64][32] On January 2, 1791, Wyandots and Lenapes attacked Big Bottom on the Muskingum River, killing eleven settlers. Soon after, Shawnees and Wyandots led by Blue Jacket unsuccessfully laid siege to Dunlap's Station on the Great Miami River. At both locations, a war club was left behind, a Native means of announcing a declaration of war.[65] Although these raids were limited in success, Sword (1985) argues they "significantly altered the course of frontier history," demonstrating that American settlement north of the Ohio River could not proceed until the United States defeated the Natives.[66] Other Native attacks followed in the coming months.[64][67]

In response to Harmar's defeat, Congress expanded the U.S. Army to two regiments in March 1791. Washington appointed Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, as major general in command.[68] St. Clair was ordered to mount another punitive expedition to the Maumee River, where he was to build a fort as a means of "awing and curbing the Indians in that quarter."[69] To augment the regular army, St. Clair was authorized to use mounted militia units to raid Native villages with the aim of deterring attacks on American settlements.[70]

In May 1791, while St. Clair gathered his army, he dispatched Brigadier General Charles Scott with 750 mounted Kentucky militiamen on a preliminary raid.[71] Natives gathered nearly 2,000 warriors at Kekionga in anticipation of facing Scott's Kentuckians, but Scott instead turned northwest and targeted undefended Wea towns on the Wabash River, destroying Ouiatenon and Kethtippecanunk (Tippecanoe).[72][73] St. Clair had hoped to start his campaign in July, but he was delayed by his own illness as well as a shortage of recruits.[73] In August, he sent Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson on a second raid, which had originally been intended as a diversion in support of the main expedition.[74] Wilkinson, with 500 mounted Kentucky militiamen, destroyed a Miami town on the Eel River.[75][76]

In September, St. Clair's men erected a supply depot, Fort Hamilton, twenty-three miles north of Fort Washington on the Great Miami.[77] The army finally left Fort Hamilton on October 4 with about 2,300 men.[78] In mid October, they stopped to build a second depot, Fort Jefferson. As the slow march toward Kekionga continued, the expedition was plagued with food shortages, plummeting morale, and frequent desertions.[79] On October 31, St. Clair sent the First Infantry Regiment southward to prevent deserters from plundering the supply convoy, depriving his army of 300 of its best troops and leaving him with about 1,400 people, including noncombatants.[80]

On November 3, St. Clair's army camped on the banks of the Wabash, near modern-day Fort Recovery, Ohio. Just before dawn on November 4, a Native force of more than 1,000 warriors led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket launched a surprise attack. Their first target was the militia, which had camped on the north side of the river. The militia retreated in panic back across the river, causing confusion in the American camp. The Americans, finding themselves surrounded, tried to organize a defense, made difficult because the Natives fired from cover, targeting officers and artillerymen. Lieutenant Colonel William Darke led a bayonet charge, temporarily creating an opening for the Natives to enter the American encampment. After three hours of fighting, St. Clair ordered a retreat, abandoning many wounded and most of the army's equipment. Among the wounded left behind was Major General Richard Butler, St. Clair's second-in-command, who was killed by Natives after the battle.[81] Fort Jefferson was too small to shelter the retreating Americans, so most fled all the way back to Fort Washington.[82]

The battle was a lopsided victory for the Natives. The Americans reported a loss of 630 soldiers killed and around 250 wounded; an additional 30 camp followers, mostly women, were also killed.[83] Native loses were comparatively slight, with 21 killed and 40 wounded.[84] Historian Colin Calloway states it was "the biggest victory Native Americans ever won and proportionately the biggest military disaster the United States ever suffered."[85]

The Natives, short on food after the destruction of their crops, scattered to hunt before winter set in.[86] Little Turtle and Blue Jacket decided to abandon Kekionga, which had proven to be vulnerable to American raids, and relocate their towns at the confluence of the Maumee and Auglaize Rivers, where the principal Shawnee chief Kekewepelethy had already settled. This move had been encouraged by British Indian agent Alexander McKee, since the new towns would be closer to the trade and military support offered by the British at Detroit.[87] This cluster of towns, known as "The Glaize," would become the headquarters of the Native confederacy for the duration of the war.[88]

1792

After St. Clair's defeat, the U.S. Congress launched an investigation of the disaster. Although St. Clair remained as territorial governor, he was forced to resign his military position.[89] President Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of defeating the Northwestern Confederacy. In March 1792, Congress passed a bill increasing the size of the army to more than 5,000 men.[90] Major General "Mad" Anthony Wayne was chosen as the new commander.[91] Congress also passed two militia acts that authorized the president to call out the militia, which had previously been under control of the states.[92]

While the American army was being readied, Washington and Knox engaged in diplomacy, hoping to buy time to prepare and to appease Americans opposed to the war.[93] In March 1792, fifty Iroquois leaders met with U.S. officials in Philadelphia where they were asked to attend an upcoming council of the Northwestern Confederacy and present U.S. peace terms.[94][95] The U.S. also tried approaching the Northwestern Confederacy directly, which proved to be difficult since the Americans continued to occupy forts north of the Ohio River. In March 1792, Wilkinson constructed Fort St. Clair to improve communications and logistics between Forts Hamilton and Jefferson.[96] The next month, Knox sent emissaries to the Natives, including John Hardin and Major Alexander Truman, veterans of the earlier campaigns; they were both killed and scalped.[97] In June, about 50 warriors attacked Fort Jefferson, killing and capturing fifteen soldiers.[98] It was during this time that Kentucky was officially admitted to the union as a state.

Rufus Putnam, who had led the settlement of Marietta, was commissioned a brigadier general and tasked with arranging a truce with the Northwestern Confederacy. Alarmed by the killing of the previous emissaries, he instead went to Vincennes and in September 1792 negotiated a treaty with tribes of the lower Wabash River.[99] Knox believed this treaty had weakened the confederacy by 800 warriors, though in fact the signers were not militant members of the confederacy. In any event, the U.S. Senate ultimately rejected the treaty because it did not specify that only the United States could purchase Native lands.[100][101][102]

Beginning in late September 1792, the Natives held a large council at the Glaize with representatives from numerous tribes, with a reported 3,600 warriors in attendance.[103] Delegates from the Iroquois, including Red Jacket, came to present the peace offer from the United States. Red Jacket advised the confederacy to accept the Muskingum River as the boundary between the United States and Native territory. The Shawnee orator Red Pole spoke on behalf of the confederacy.[104] Red Pole denounced the Iroquois for meeting privately with the Americans to discuss further land cessions. "We do not want compensation" from the Americans, said Red Pole. "We want restitution of our country."[105] After much debate, the council endorsed Red Pole's position: the Ohio River was the only acceptable boundary and American forts north of the river must be destroyed. The council also agreed to meet with the Americans in 1793.[106]

When Red Jacket reported the decision of council to an American official in November, he omitted the confederacy's demands about the Ohio River boundary and the destruction of the forts. As a result, the Americans were given an erroneous impression that the confederacy was prepared to accept U.S. terms. Knox agreed to send treaty commissioners to the 1793 council and suspend all offensive operations until that time, angering General Wayne, who had hoped to launch the next American invasion in 1793.[107]

Following the Glaize meeting, Red Pole began an extensive tour of the south, an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to enlist more Chickamauga Cherokees and Creeks in the confederacy.[108] Meanwhile, on November 6, Little Turtle and about 200 Miamis and Shawnees attacked a supply convoy near Fort St. Clair, killing six Americans and depriving them of the packhorses needed to supply the forts. "It is a most disagreeable and humiliating position to remain with our hands tied whilst the enemy is at liberty to act upon the offensive," wrote Wayne to Knox.[109][110]

1793

While General Wayne awaited the outcome of the peace negotiations, he prepared his army known as the Legion of the United States at Legionville, a camp on the Ohio River near Pittsburgh. Wayne believed the previous expeditions had failed due to lack of discipline, and so he thoroughly trained his troops, flogging soldiers for infractions and hanging deserters.[112] By May 5, 1793, the Legion had relocated to a camp near Fort Washington, where Wayne awaited word to begin his invasion.[113]

In mid-May, Benjamin Lincoln, Beverley Randolph, and Timothy Pickering – the U.S. commissioners appointed to meet with the Native confederacy – arrived at Fort Niagara at the western end of Lake Ontario, traveling by way of the Great Lakes to avoid the fates of John Hardin and Alexander Truman the previous year.[114][115] Niagara was one of the forts still occupied by the British in defiance of the 1783 Paris treaty, but John Graves Simcoe, the British lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, housed the commissioners at his own residence.[115] Despite his cordiality, Simcoe had been working to undermine U.S. influence among the Natives. After the recent Native victories, he had hoped Great Britain would support the creation of a Native buffer state between the United States and Canada, an idea the Americans opposed.[116] With the outbreak of war in Europe between France and Great Britain in 1793, Simcoe faced a dilemma. He had to keep peace with the United States to avoid opening another front in the war with France, while at the same time maintain British influence among the Natives in case they were needed to help defend Upper Canada against the Americans.[117]

At Niagara, the U.S. commissioners were visited by a Native delegation led by Brant. Although Brant had been one of the principal organizers of the Northwestern Confederacy, he was now regarded with suspicion by the more militant members because of his willingness to negotiate with the Americans and because the Iroquois had not participated in the war. Nevertheless, Brant spoke for the delegation, asking if the commissioners were authorized to create a new boundary line and inquiring why Wayne's army was preparing for war while peace negotiations were underway. The commissioners assured Brant they were authorized to negotiate a boundary and that hostilities had been officially suspended. Brant returned to the Maumee and reported to the confederacy, and although he had some supporters, he was denounced for not insisting on the Ohio River boundary. A new delegation (without Brant) was sent to meet the commissioners on the Detroit River.[118][119]

This second meeting, held at British Indian agent Matthew Elliot's estate near Amherstburg, began on July 30. The Wyandot chief Carry-One-About (So-Wagh-da-Wunk) spoke for the confederacy, with Buckongahelas (Lenape) and Kekewepelethy in attendance. The confederacy presented its ultimatum: the Ohio River was the only acceptable boundary, and forts and settlers north of the river must be removed. The commissioners replied that since lands north of the Ohio had already been sold and settled by Americans, those lands could not be returned. The Native delegates returned to the Maumee to confer with the council. Brant once again argued for compromise, but he lost out to the militants, who had the support of Alexander McKee.[120] On August 13, the confederacy sent a written declaration to the U.S. commissioners, signed by representatives of all the nations except the Iroquois. According to Sugden (2000), this document was "the defiant and frank sentiments of proud, undefeated peoples, asserting their independence and sovereignty and rebutting the pretensions of those who would dispossess and humble them."[121] The confederacy offered a solution: the U.S. should use the money it would spend on buying land and fighting a war and instead pay the settlers to relocate south of the Ohio River. These terms were unacceptable to the Americans, and the commissioners replied that "the negotiation is therefore at an end."[122] Back on the Maumee, Brant bitterly announced the Iroquois could no longer assist the confederacy in the fighting that was sure to follow and the Iroquois must now "remove our people from among the Americans."[123]

Upon learning that negotiations had failed, Wayne advanced, reaching Fort Jefferson on October 13 with 2,600 men.[124] On October 17, an Odawa war party under Little Otter attacked a supply convoy south of Fort Jefferson, killing fifteen and capturing ten.[125] Wayne was compelled to use more troops to guard his supply line. Given these problems, Wayne decided to halt major operations and build Fort Greenville north of Fort Jefferson. "I am at a loss to determine what the savages are about, and where they are," he wrote to Knox in November.[126] The Natives were having logistical problems of their own, with many warriors scattering for the winter hunt.[127] The Legion wintered at Fort Greenville, but on December 23 Wayne led a detachment of about 300 men to the site of St. Clair's defeat. There, his troops built Fort Recovery, buried the American dead still on the battlefield, and recovered three of the cannon lost there in 1791.[128][129]

1794

In January 1794, the confederacy sent a delegation to Fort Greenville to arrange the release of two Lenape women held by the Americans. A Lenape chief asked if Wayne was willing to hold peace talks. Wayne said he would only negotiate if the Natives recalled their war parties and released all American prisoners within the next thirty days.[130][131][132] Back at the Glaize, militant leaders, surprised that talks had been initiated without authorization from the confederacy, debated the proposal. The militants prevailed, and the matter was dropped.[133][134]

In February 1794, Lord Dorchester told an Iroquois delegation in Quebec that Great Britain could be at war with the United States within the year and that Native lands lost to the Americans would be restored.[135][136] Dorchester ordered Simcoe to build a fort on the Maumee to defend Detroit from the advancing Americans. In April, Simcoe constructed Fort Miami and garrisoned it with 120 soldiers and an artillery detachment.[137] Dorchester's words and actions caused an uproar in the United States; the construction of Fort Miami on what Americans regarded as their territory was considered an act of aggression.[138] In May, Chief Justice John Jay was dispatched to England to negotiate a resolution to the crisis.[139] The Native confederacy, encouraged by British actions, sent out messengers to recruit additional warriors.[140]

Battle of Fort Recovery

At Fort Greenville, Wayne was delayed by supply problems, but the construction of Fort Miami compelled him to accelerate his schedule. Eager to begin operations, he impatiently awaited the arrival of a reinforcement of Kentucky militiamen.[141] In late June, Wayne was joined by about 100 Chickasaws and Choctaws, who had come from the south to fight against their traditional enemies in the Northwestern Confederacy.[142] On June 27, forty-five Choctaws and ten scouts led by William Wells, Wayne's principal scout,[143] skirmished with a large body of Natives advancing from the Glaize. Wells reported to Wayne that Fort Recovery was in danger of imminent attack.[144]

The Native army marching toward Fort Recovery numbered 1,200 warriors, the largest force the confederacy had yet fielded.[145] Unlike the Americans, the Natives did not have an overall commander. Instead, military decisions were made by a council of leading chiefs and warriors.[146] Blue Jacket urged the council to bypass Forts Recovery and Greenville and attack the American supply lines, cutting off Wayne's Legion. Recently arrived Three Fire leaders, whose warriors comprised the majority of the army, favored attacking a convoy near Fort Recovery. They prevailed in the council, and so on June 30 warriors ambushed the convoy then rushed the fort, but they were driven off by American musket fire and artillery.[147][148] The attack's failure discouraged the Three Fires contingent, who accused the Shawnees of insufficient support. They went home, depriving Blue Jacket of about half his army, which returned to the Glaize.[149][150] After the battle, Little Turtle and Tarhe (Wyandot) made trips to Detroit to ask the British for support, as Blue Jacket had done on previous occasions, but the commander, Lieutenant Colonel Richard G. England, told the Natives he could not fight the Americans without orders.[151][150]

Battle of Fallen Timbers

On the morning of August 20, the Legion broke camp and marched toward the Maumee River near modern Toledo, Ohio, where an ambush had been set by the Confederacy. The Legion had been reduced to about 3,000 soldiers and militia, with many soldiers defending the supply trains and forts. Blue Jacket had selected a battlefield where a tornado had felled hundreds of trees, creating a natural defensive barrier.[152] Here he placed confederation forces of about 1,500 warriors: Blue Jacket's Shawnees, Delawares led by Buckongahelas, Miamis led by Little Turtle, Wyandots led by Tarhe[153] and Roundhead, Mingos, a small detachment of Mohawks, and a British company of Canadian militiamen dressed as Native Americans under William Caldwell.[154]

Odawa and Potawatomi under Little Otter and Egushawa occupied the center and initiated the attack against the Legion's scouts. Front elements of the Legion's columns initially collapsed under pursuing Native Americans. Wayne immediately committed his reserves to the center to halt their advance and divided his infantry into two wings, the right commanded by Wilkinson, the other by Hamtramck. The Legion's cavalry secured the right along the Maumee River. General Scott provided a brigade of mounted militia to guard the open left flank, while the rest of the Kentucky militia formed a reserve.[152] Once contact had been established, U.S. scouts identified the location of Confederacy warriors, and Wayne ordered an immediate bayonet charge. Legion dragoons also charged and attacked with sabres. Blue Jacket's warriors fled from the battlefield to regroup at nearby Fort Miami but found the doors of the fort locked by the British garrison. (Britain and the United States were by then reaching a close rapprochement to counter Jacobin France in the French Revolution.) The entire battle lasted little more than an hour.[155] The Legion had significant casualties, with 33 men killed and 100 wounded. The Confederacy had between 19 and 40 warriors killed and an unknown number wounded.[156] The battle fostered distrust between the Native nations and between the confederacy and the British; it was the last time the Northwestern Confederacy gathered a large military force to oppose the United States.

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami, which was under command of British Major William Campbell. When Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians.[157] The next day, Wayne rode alone to Fort Miami and slowly conducted an inspection of the fort's exterior walls. The British garrison debated whether to engage Wayne, but in the absence of orders and being already at war with France, Campbell declined to fire the first shot at the United States.[158] The Legion, meanwhile, destroyed Indian villages and crops in the region of Fort Deposit and burned Alexander McKee's trading post within sight of Fort Miami before withdrawing.[159]

Wayne's Legion finally arrived at Kekionga on September 17, 1794, and Wayne personally selected the site for a new U.S. fort.[160] Wayne wanted a strong fort built, capable of withstanding a possible attack by Indians and by the British forces from Fort Detroit. The fort was finished by October 17 and was capable of withstanding 24-pound cannon. It was named Fort Wayne and placed under command of Hamtramck, who had been commandant of Fort Knox in Vincennes. The fort was officially dedicated October 22,[160] the fourth anniversary of Harmar's defeat, and the day is considered the founding of the modern city of Fort Wayne, Indiana.[161] That winter, Wayne also reinforced his line of defensive forts with Fort St. Marys, Fort Loramie, and Fort Piqua.

Treaty of Greenville and Jay Treaty

Within months of Fallen Timbers, the United States and Great Britain negotiated the Jay Treaty,[162] which required British withdrawal from the Great Lakes forts while opening up some British territory in the Caribbean for American trade. The treaty also encoded free trade and freedom of movement for Native Americans living in territories controlled by either the United States or Great Britain.[163] The Jay Treaty was ratified by the United States Senate in 1795[162] and was used by Wayne as evidence that Great Britain would no longer support the confederacy.[164] The Jay Treaty and U.S. relations with Great Britain remained as political issues in the 1796 United States presidential election in which John Adams beat Jay Treaty opponent Thomas Jefferson.

The United States also negotiated the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.[165] Utilizing St. Clair's defeat and Fort Recovery as a reference point,[166] the Greenville Treaty Line forced the northwest Native American tribes to cede southern and eastern Ohio and various tracts of land around forts and settlements in Illinois Country; to recognize the U.S. rather than Britain as the ruling power in the Old Northwest; and to surrender ten chiefs as hostages until all American prisoners were returned. The Miami also lost private control of the Kekionga portage, since the Northwest Ordinance passed by Congress guaranteed free use of important portages in the region.[167]

Aftermath

Fort Lernoult and Fort Miami were abandoned by the British in 1796 as a condition of the Jay Treaty. After two decades of efforts to take Detroit, U.S. forces under Colonel Hamtramck occupied Fort Lernoult the next day. The U.S. renamed Fort Lernoult to Fort Detroit and abandoned Fort Miami in 1799. The British re-captured Fort Detroit and Fort Miami during the War of 1812. Fort Detroit was abandoned one year later as American forces advanced towards it, and Fort Miami was abandoned in 1814 and eventually demolished.

Most of the western U.S. forts were also abandoned after 1796; Fort Washington, the last, was moved across the Ohio River to Kentucky in 1804 to make room for a growing settlement at Cincinnati; it became the Newport Barracks.[168] General Wayne supervised the surrender of British posts in the Northwest Territory and personally selected the construction site of Fort Wayne in Kekionga to secure his Legion's victory.[169]

Wayne died during a return trip to Pennsylvania from a military post in Detroit on December 15, 1796, one year after the ratification of the Treaty of Greenville.[170] Wayne's second in command, General Wilkinson, was named as the new commander of U.S. forces. It was later learned that Wilkinson had secretly tried to undermine Wayne throughout the campaign, writing negative letters to civilian leaders and anonymously to local newspapers. Wilkinson was also a Spanish agent at the time.[171] It has been speculated but never proven that Wilkinson had Wayne assassinated.[172][173]

After the end of hostilities, large numbers of United States settlers migrated to the Northwest Territory. Many made unscrupulous land deals with the Native nations, forcing General Wilkinson to invalidate them in a 1796 proclamation.[174] Five years after the Treaty of Greenville, Ohio was split from the Northwest Territory, closely following the line of advanced forts and the Greenville Treaty Line. The territory west of that border was named Indiana Territory. In February 1803, the state of Ohio was admitted to the Union.[note 1]

Legacy

President Thomas Jefferson hoped to incorporate Native Americans through assimilation and intermarriage, but encouraged land removals and debts as a way to humble Native leaders.[175] Territorial governor William Henry Harrison began an aggressive campaign of native land acquisition. Native Americans were subjected to diseases, debts, drunkenness, and sexual abuse at the hands of the new settlers.[176] In 1805, Tenskwatawa began a traditionalist movement that rejected United States practices. His followers settled at Prophetstown in Indiana Territory, leading to Tecumseh's War and the Northwest theater of the War of 1812. United States settlement continued, fueling Indian removals and conflicts in the Northwest Territory well into the 1830s. These include the Black Hawk War and the Potawatomi Trail of Death. Wisconsin, the last state fully located in the Northwest Territory, was admitted to the union in 1848. The process of acquiring cheap land and selling it to white settlers was a critical means of paying off the United States' national debt in the 1830s.[175]

Before his death, Little Turtle lamented "More of us have died since the Treaty of Greenville than we lost by the years of war before."[177] Contributors to the Journal of Genocide Research characterize the United States' campaigns in the Northwest Territory as attempted genocide, citing descriptions by Secretary of War Henry Knox of the Shawnee, Cherokee, and Wabash as "banditti" and subsequent orders to "extirpate, utterly, if possible, the said banditti." They argue that the ultimate goal of Knox and other American officials was to depopulate the region of Native Americans and open up its lands to white settlement.[178][179][53]

Future Native American resistance movements were unable to form a union matching the size or capability that the Northwestern Confederacy had displayed. Author Wiley Sword writes that although the 19th century American Indian Wars received more attention, their fates were determined during wars of the 1790s.[180] American historians of the 19th century largely ignored this war, which did not fit their patriotic narrative.[181] As such, there is no standard name or starting date for this war. According to Hogeland (2017), "The first war the United States ever fought, in which the U.S. Army itself came into being, would never even be given a name."[182] In 1914, a publication referred to the conflict as the "Northwest Indian Wars, Ohio" dating it from 1790 to 1795, although it also called the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe the "Northwest Indian War, Indiana".[183] A frequently cited 1964 PhD dissertation calls it the "Northwest Indian War, 1784–1795."[184][185] In other publications of this era, it was known as "Little Turtle's War." In the first book-length study of the war, Sword (1985) refers to it as the "United States-Indian War of 1790 to 1795."[186] Sugden (2000) gives an earlier start date, referring to the "Indian war of 1786 to 1795."[187] A 2001 study suggests naming the conflict the "Miami Confederacy War," but Grenier (2005) disagrees, since the war involved Ohio Native tribes, and suggests the "Ohio Indian War of 1790–1795" instead, although noting historians had taken to calling it the "Northwest Indian War."[188]

Because all active duty units (except one field artillery company) were disbanded after the American Revolution, the Northwest Indian War is among earliest campaign listed in United States Army lineages. It is noted with the Indian Wars Campaign streamer.[189][note 2]

Key figures

Several veterans of the Northwest Indian War are known for their later achievements, including William Henry Harrison, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis,[190] and Tecumseh. William Wells, who fought on both sides of the war, later died at the Battle of Fort Dearborn.

United States

- Henry Knox, first United States Secretary of War

- Josiah Harmar, Brigadier General in command of the First American Regiment who led the 1790 Harmar campaign

- Arthur St. Clair, Governor of the Northwest Territory and Major General at St. Clair's defeat

- Anthony Wayne, Major General in command of Legion of the United States at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

- Charles Scott, Brigadier General commanding the Kentucky militia during Wayne's campaign

- James Wilkinson, Lieutenant Colonel in command of Fort Washington, Wayne's second in command and Spanish spy

United Indian Nations

- Little Turtle - a Sagamore (chief) of a Miami band and celebrated war leader in the confederacy.

- Blue Jacket - a principle war chief of the Shawnee and a primary war leader of the confederacy.

- Egushawa - a chief of the Ottawa nation and influential leader in the confederacy.

- Buckongahelas - a chief from the Lenape (Delaware) who resisted the United States and closely allied with Blue Jacket.

- Roundhead (or Stayeghtha) - an American Indian chief of the Wyandot people, present at Fallen Timbers.

- Joseph Brant - a prominent Mohawk leader who helped form the Northwest Confederacy.

British Empire

- Sir Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester Commander-in-Chief of British North America

- William Campbell, British Major in command of Fort Miamis

- John Graves Simcoe Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada

- Alexander McKee Deputy Agent and later Deputy Superintendent General in the British Indian Department

See also

- Cherokee–American wars, corresponding war in the Old Southwest

Notes

Citations

- "Indian Wars Campaigns". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 29–30.

- Calloway 2018, pp. 191–95.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 37–38.

- Calloway 2018, p. 191.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 39–40.

- Calloway 2018, p. 210.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 40–45.

- Calloway 2018, p. 211.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 74.

- Calloway 2018, p. 212.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 78.

- Sugden 2000, p. 65.

- Werther, Richard J. (5 January 2023). "The "Western Forts" of the 1783 Treaty of Paris". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- Heath 2015, p. 64.

- Sugden 2000, p. 66.

- Sugden 2000, p. 67.

- Calloway 2018, pp. 293, 308.

- Calloway 2015, p. 42.

- Calloway 2018, p. 300.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 73–74.

- Sword 1985, p. 31.

- Sword 1985, pp. 33–37.

- Sword 1985, pp. 37–41.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 74–75.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 79–80.

- Sugden 2000, p. 77.

- Calloway 2015, pp. 48–50.

- Calloway 2015, pp. 53, 58.

- Heath 2015, pp. 103–04.

- Sugden 2000, p. 84.

- Heath 2015, p. 127.

- Calloway 2015, p. 59.

- Sword 1985, p. 67.

- Sword 1985, p. 75–77.

- Sword 1985, p. 77.

- Sword 1985, p. 87.

- Sword 1985, p. 79.

- Sword 1985, p. 82.

- Nelson 1986, p. 223.

- Winkler 2011, p. 15.

- Calloway 2015, pp. 63–65.

- Calloway 2015, p. 64.

- Calloway 2015, p. 66.

- Sugden 2000, p. 100.

- Sugden 2000, p. 101.

- Sword 1985, p. 103.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 101–02.

- Sword 1985, pp. 106–09.

- Sugden 2000, p. 102.

- Sudgen, p. 103.

- Sword 1985, p. 110.

- Mann, Barbara Alice (22 May 2013). "Fractal massacres in the Old Northwest: the example of the Miamis". Journal of Genocide Research. 15 (2): 167–82. doi:10.1080/14623528.2013.789203. S2CID 71986573. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- Sword 1985, pp. 111–12.

- Sword 1985, pp. 113–16.

- Sugden 2000, p. 104.

- Sword 1985, pp. 117–19.

- Sugden 2000, p. 105.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 106–07.

- Sword 1985, p. 122.

- Sword 1985, p. 124.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 115.

- Sword 1985, p. 121.

- Calloway 2015, p. 69.

- Sword 1985, p. 130.

- Sword 1985, pp. 130–31.

- Heath 2015, p. 128.

- Calloway 2015, p. 71.

- Sword 1985, p. 145.

- Calloway 2015, p. 72.

- Sword 1985, p. 139.

- Sword 1985, pp. 140–41.

- Calloway 2015, p. 75.

- Sword 1985, p. 159.

- Sword 1985, pp. 155–56.

- Calloway 2015, p. 76.

- Sword 1985, p. 160.

- Sword 1985, p. 161.

- Sword 1985, pp. 163–66.

- Sword 1985, pp. 167, 195.

- Sword 1985, pp. 176–88.

- Sword 1985, pp. 192–94.

- Calloway 2015, p. 127.

- Sword 1985, p. 191.

- Calloway 2015, p. 5.

- Sword 1985, p. 196.

- Hogeland 2017, pp. 145–47.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 130–31.

- Sword 1985, p. 202.

- Sword 1985, p. 204.

- Sword 1985, pp. 205–06.

- Calloway 2015, p. 143.

- Sword 1985, pp. 208–14.

- Sword 1985, pp. 208–09.

- Hogeland 2017, pp. 226–28.

- Sword 1985, p. 218.

- Calloway 2015, p. 141.

- Sword 1985, p. 219.

- Sword 1985, pp. 212–13.

- Sword 1985, pp. 217–18.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 256.

- Calloway 2015, p. 142.

- Calloway 2015, p. 145.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 134–35.

- Sugden 2000, p. 138.

- Sword 1985, pp. 226–27.

- Sword 1985, pp. 227–28.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 138–41.

- Sword 1985, pp. 220–21.

- Hogeland 2017, pp. 264–71.

- Seeley 2021, p. 118.

- Sword 1985, pp. 232–35.

- Sword 1985, p. 236.

- Gaff 2004, p. 105.

- Sword 1985, pp. 238–40.

- Sugden 2000, p. 145.

- Sword 1985, pp. 229–31, 240–41.

- Sword 1985, pp. 241–43.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 149–50.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 152–53.

- Sugden 2000, p. 153.

- Sword 1985, p. 246.

- Sword 1985, p. 247.

- Sword 1985, pp. 249–52.

- Sword 1985, p. 251.

- Sword 1985, pp. 251–53.

- Sword 1985, p. 254.

- Gaff 2004, pp. 184–86.

- Sword 1985, pp. 254–56.

- Sword 1985, p. 256.

- Sugden 2000, p. 157.

- Heath 2015, p. 189.

- Sword 1985, p. 257.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 157–58.

- Sword 1985, p. 258.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 158–59.

- Sword 1985, pp. 261–62.

- Sword 1985, p. 262.

- Sword 1985, p. 260.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 159–62.

- Sword 1985, pp. 264–66.

- Sword 1985, p. 269.

- Sword 1985, p. 283.

- Heath 2015, p. 195.

- Sugden 2000, pp. 163–64.

- Sugden 2000, p. 163.

- Sword 1985, pp. 271, 275–76.

- Sugden 2000, p. 166.

- Sugden 2000, p. 168.

- Sword 1985, pp. 277–78.

- Sugden 2000, p. 169.

- Seelinger, Matthew (16 July 2014). "The Battle of Fallen Timbers, 20 August 1794". National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Stockwell 2018, p. 264.

- Sword 1985, p. 298.

- Sword 1985, p. 306.

- Gaff 2004, p. 327.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 350.

- Hogeland 2017, pp. 350–51.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 351.

- Poinsatte 1976, pp. 27–28.

- "Fort Wayne: History". Allen County History Center. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "John Jay's Treaty, 1794–95". Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute. United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "First Nations and Native Americans". U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Canada. United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Sword 1985, p. 328.

- Gaff 2004, p. 366.

- "Treaty of Greene Ville". Touring Ohio. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Poinsatte 1976, p. 30.

- Suess, Jeff (28 December 2013). "Cincinnati's beginning: The origin of the settlement that became this city". cincinnati.com. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Poinsatte 1976, p. 27.

- Gaff 2004, p. 367.

- "This Day in History: The Secret Plot Against General Mad Anthony Wayne". Taraross. 25 January 2019.

- Harrington, Hugh T. (20 August 2013). "Was General Anthony Wayne Murdered?". Journal of the American Revolution.

- "Why I Believe Meriwether Lewis Was Assassinated | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org.

- Sword 1985, p. 337.

- Sword 1985, p. 338.

- Sword 1985, pp. 338–39.

- Sword 1985, p. 335.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (3 February 2016). "'Just and lawful war' as genocidal war in the (United States) Northwest Ordinance and Northwest Territory, 1787–1832". Journal of Genocide Research. 18 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/14623528.2016.1120460. S2CID 74337505. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (October 2015). ""To Extirpate the Indians": An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s–1810". The William and Mary Quarterly. 72 (4): 587–622. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.72.4.0587. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.72.4.0587. S2CID 146642401. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Sword 195, p. 340.

- Calloway 2015, p. 8.

- Hogeland 2017, p. 17.

- Strait, Newton A. (1914). Alphabetical List of Battles 1754–1900. Washington, DC. p. 231. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sudgen 2000, p. 287 n.1.

- Nelson 1985, p. 352.

- Sword 1985, p. xiii.

- Sudgen 2000, p. 287 n. 1.

- Grenier 2005, pp. 193–94 n. 85.

- "Indian Wars Campaigns". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "Meriwether Lewis". Virginia Center for Digital History. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

References

- Barnes, Celia (2003). Native American Power in the United States, 1783–1795. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0838639580.

- Calloway, Colin G. (2015). The Victory with No Name: the Native American Defeat of the First American Army. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01993-8799-1.

- Calloway, Colin G. (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190652166. LCCN 2017028686.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Fernandes, Melanie L. (2016). "'Under the auspices of peace': The Northwest Indian War and its Impact on the Early American Republic". The Gettysburg Historical Journal. 15 (Article 8)., Available at: "Under the auspices of peace": The Northwest Indian War and its Impact on the Early American Republic

- Gaff, Alan D. (2004). Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Wayne's Legion in the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3585-9.

- Grenier, John (2005). The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44470-5.

- Heath, William (2015). William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806151472.

- Hogeland, William (2017). Autumn of the Black Snake. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374107345. LCCN 2016052193.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253307511.

- Nelson, Paul David (1986). "General Charles Scott, the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers, and the Northwest Indian Wars, 1784–1794". Journal of the Early Republic. 6 (3): 219–51. doi:10.2307/3122915. JSTOR 3122915.

- Poinsatte, Charles (1976). Outpost in the Wilderness: Fort Wayne, 1706–1828. Allen County, Indiana: Fort Wayne Historical Society. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1896). St. Clair's Defeat, 1791. Fort Wayne: Fort Wayne Convention Bureau.

- Seeley, Samantha (2021). Race, Removal, and the Right to Remain: Migration and the Making of the United States. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469664828.

- Stockwell, Mary (2018). Unlikely General: "Mad" Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300235104.

- Sugden, John (2000). Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4288-3.

- Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790–1795. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2488-1.

- Van Every, Dale (2018) [1962]. A Company of Heroes: The American Frontier: 1775–1783 (The Frontier People of America Book 2) (Kindle ed.). New York: William Morrow, Ltd. – via Endeavour Media.

- Van Every, Dale (2018) [1963]. Ark of Empire: The American Frontier: 1784–1803 (The Frontier People of America) (Kindle ed.). New York: Morrow – via Endeavour Media.

- Winkler, John F. (2011). Wabash 1791: St. Clair's defeat. Illustrated by Peter Dennis. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.

- Winkler, John F. (2013). Fallen Timbers 1794: The US Army's First Victory. Illustrated by Peter Dennis. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1780963754.