Causes of seizures

Generally, seizures are observed in patients who do not have epilepsy.[1] There are many causes of seizures. Organ failure, medication and medication withdrawal, cancer, imbalance of electrolytes, hypertensive encephalopathy, may be some of its potential causes.[2] The factors that lead to a seizure are often complex and it may not be possible to determine what causes a particular seizure, what causes it to happen at a particular time, or how often seizures occur.[3]

Diet

Malnutrition and overnutrition may increase the risk of seizures.[4] Examples include the following:

- Vitamin B1 deficiency (thiamine deficiency) was reported to cause seizures, especially in alcoholics.[5][6][7]

- Vitamin B6 depletion (pyridoxine deficiency) was reported to be associated with pyridoxine-dependent seizures.[8]

- Vitamin B12 deficiency was reported to be the cause of seizures for adults[9][10] and for infants.[11][12]

Folic acid in large amounts was considered to potentially counteract the antiseizure effects of antiepileptic drugs and increase the seizure frequency in some children, although that concern is no longer held by epileptologists.[13]

Medical conditions

Those with various medical conditions may experience seizures as one of their symptoms. These include:

- Aneurysm, especially of blood vessels in or near the brain, cranium (skull), and neck/upper spine

- Angelman syndrome

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Brain abscess

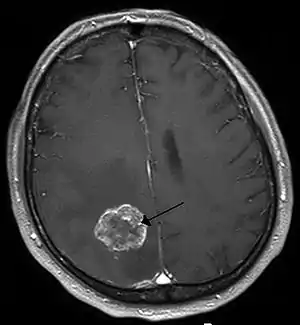

- Brain tumor

- Cavernoma

- Cerebral palsy

- Down syndrome

- Eclampsia, as well as other crises of pregnancy involving extreme hypertension or significant increases in intracranial pressure

- Epilepsy

- Encephalitis

- Fragile X syndrome

- Meningitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Organ failure, especially of the brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and endocrine/exocrine organs- if it is severe enough and remains untreated and not fully corrected

- Stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic types)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Tuberous sclerosis

Other conditions have been associated with lower seizure thresholds and/or increased likelihood of seizure comorbidity (but not necessarily with seizure induction). Examples include depression, psychosis, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism, among many others.

Drugs

Adverse effect

Seizures may occur as an adverse effect of certain drugs. These include:

- Aminophylline

- Bupivicaine

- Bupropion

- Butyrophenones

- Caffeine (in high amounts of 500 mgs and above could increase the occurrence of seizures,[14] particularly if normal sleep patterns are interrupted)

- Chlorambucil

- Ciclosporin

- Clozapine

- Corticosteroids

- Diphenhydramine

- Enflurane

- Estrogens

- Fentanyl

- Insulin

- Lidocaine

- Maprotiline

- Meperidine

- Olanzapine

- Pentazocine

- Phenothiazines (such as chlorpromazine)

- Prednisone

- Procaine

- Propofol

- Propoxyphene

- Quetiapine

- Risperidone

- Sevoflurane

- Theophylline

- Tramadol

- Tricyclic antidepressants (especially clomipramine)

- Venlafaxine

- The following antibiotics: isoniazid, lindane, metronidazole, nalidixic acid, and penicillin, though vitamin B6 taken along with them may prevent seizures; also, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems

Use of certain recreational drugs may lead to seizures in some, especially when used in high doses or for extended periods. These include amphetamines (such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDMA ("ecstasy"), and mephedrone), cocaine, methylphenidate, psilocybin, psilocin, and GHB.

If treated with the wrong kind of antiepileptic drugs (AED), seizures may increase, as most AEDs are developed to treat a particular type of seizure.

Convulsant drugs (the functional opposites of anticonvulsants) will always induce seizures at sufficient doses. Examples of such agents — some of which are used or have been used clinically and others of which are naturally occurring toxins — include strychnine, bemegride, flumazenil, cyclothiazide, flurothyl, pentylenetetrazol, bicuculline, cicutoxin, and picrotoxin.

Alcohol

There are varying opinions on the likelihood of alcoholic beverages triggering a seizure. Consuming alcohol may temporarily reduce the likelihood of a seizure immediately following consumption. But, after the blood alcohol content has dropped, chances may increase. This may occur, even in non-epileptics.[15]

Heavy drinking in particular has been shown to possibly have some effect on seizures in epileptics. But studies have not found light drinking to increase the likelihood of having a seizure at all. EEGs taken of patients immediately following light alcohol consumption have not revealed any increase in seizure activity.[16]

Consuming alcohol with food is less likely to trigger a seizure than consuming it without.[17]

Consuming alcohol while using many anticonvulsants may reduce the likelihood of the medication working properly. In some cases, it may trigger a seizure. Depending on the medication, the effects vary.[18]

Drug withdrawal

Some medicinal and recreational drugs can dose-dependently precipitate seizures in withdrawal, especially when withdrawing from high doses and/or chronic use. Examples include drugs that affect GABAergic and/or glutamatergic systems, such as alcohol (see alcohol withdrawal),[19] benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and anesthetics, among others.

Sudden withdrawal from anticonvulsants may lead to seizures. It is for this reason that if a patient's medication is changed, the patient will be weaned from the medication being discontinued following the start of a new medication.

Missed anticonvulsants

A missed dose or incorrectly timed dose of an anticonvulsant may be responsible for a breakthrough seizure, even if the person often missed doses in the past, and has not had a seizure as a result.[20] Missed doses are one of the most common reasons for a breakthrough seizure. A single missed dose is capable of triggering a seizure in some patients.[21]

- Incorrect dosage amount: A patient may be receiving a sub-therapeutic level of the anticonvulsant.[22]

- Switching medicines: This may include withdrawal of anticonvulsant medication without replacement, replaced with a less effective medication, or changed too rapidly to another anticonvulsant. In some cases, switching from brand to a generic version of the same medicine may induce a breakthrough seizure.[23][24]

Fever

In children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, a fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or higher may lead to a febrile seizure.[25] About 2-5% of all children will experience such a seizure during their childhood.[26] In most cases, a febrile seizure will not indicate epilepsy.[26] Approximately 40% of children who experience a febrile seizure will have another one.[26]

In those with epilepsy, fever can trigger a seizure. Additionally, in some, gastroenteritis, which causes vomiting and diarrhea, can lead to diminished absorption of anticonvulsants, thereby reducing protection against seizures.[27]

Vision

In some epileptics, flickering or flashing lights, such as strobe lights, can be responsible for the onset of a tonic clonic, absence, or myoclonic seizure.[28] This condition is known as photosensitive epilepsy and, in some cases, the seizures can be triggered by activities that are harmless to others, such as watching television or playing video games, or by driving or riding during daylight along a road with spaced trees, thereby simulating the "flashing light" effect. Some people can have a seizure as a result of blinking one's own eyes.[29] Contrary to popular belief, this form of epilepsy is relatively uncommon, accounting for just 3% of all cases.[30]

A routine part of the EEG test involves exposing the patient to flickering lights to attempt to induce a seizure, to determine if such lights may be triggering a seizure in the patient, and to be able to read the wavelengths when such a seizure occurs.[29]

In rare cases seizures may be triggered by not focusing.[31]

Head injury

A severe head injury, such as one sustained in a motor vehicle accident, fall, assault, or sports injury, can result in one or more seizures that can occur immediately after the fact or up to a significant amount of time later.[32] This could be hours, days, or even years following the injury.

A brain injury can cause seizure(s) because of the unusual amount of energy that is discharged across of the brain when the injury occurs and thereafter. When there is damage to the temporal lobe of the brain, there is a disruption of the supply of oxygen.[33]

The risk of seizure(s) from a closed head injury is about 15%.[34] In some cases, a patient who has had a head injury is given anticonvulsants, even if no seizures have occurred, as a precaution to prevent them in the future.[35]

Hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia

Hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, can increase frequency of seizure. The probably mechanism is that elevated extracellular glucose level increases neuronal excitability.[36]

Curiously, hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, can also trigger seizures.[37] The mechanism is also increased cortical excitability.[38]

Menstrual cycle

In catamenial epilepsy, seizures become more common during a specific period of the menstrual cycle.

Sleep deprivation

Sleep deprivation is the second most common trigger of seizures.[15] In some cases, it has been responsible for the only seizure a person ever has.[39] However, the reason for which sleep deprivation can trigger a seizure is unknown. One possible thought is that the amount of sleep one gets affects the amount of electrical activity in one's brain.[40]

Patients who are scheduled for an EEG test are asked to deprive themselves of some sleep the night before to be able to determine if sleep deprivation may be responsible for seizures.[41]

In some cases, patients with epilepsy are advised to sleep 6-7 consecutive hours as opposed to broken-up sleep (e.g., 6 hours at night and a 2-hour nap) and to avoid caffeine and sleeping pills in order to prevent seizures.[42]

Parasites and stings

In some cases, certain parasites can cause seizures. The Schistosoma sp. flukes cause Schistosomiasis. Pork tapeworm and beef tapeworm cause seizures when the parasite creates cysts at the brain. Echinococcosis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, African trypanosomiasis, and many other parasitic diseases can cause seizures.

Seizures have been associated with insect stings. Reports suggest that patients stung by red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) and Polistes wasps had seizures because of the venom.[43][44]

In endemic areas, neurocysticercosis is the main cause behind focal epilepsy in early adulthood. All growth phases of cysticerci (viable, transitional and calcified) are associated with epileptic seizures. Thus, anti-cysticercus treatment helps by getting rid of it thus lowers the risk of recurrence of seizures in patients with viable cysts. Symptomatic epilepsy can be the first manifestation of neuroschistosomiasis in patients without any systemic symptoms. The pseudotumoral form can trigger seizures secondary to the presence of granulomas and oedemas in the cerebral cortex.[45]

Stress

Stress can induce seizures in people with epilepsy, and is a risk factor for developing epilepsy. Severity, duration, and time at which stress occurs during development all contribute to frequency and susceptibility to developing epilepsy. It is one of the most frequently self-reported triggers in patients with epilepsy.[46][47]

Stress exposure results in hormone release that mediates its effects in the brain. These hormones act on both excitatory and inhibitory neural synapses, resulting in hyper-excitability of neurons in the brain. The hippocampus is known to be a region that is highly sensitive to stress and prone to seizures. This is where mediators of stress interact with their target receptors to produce effects.[48]

"Epileptic fits" as a result of stress are common in literature and frequently appear in Elizabethan texts, where they are referred to as the "falling sickness".[49]

Breakthrough seizure

A breakthrough seizure is an epileptic seizure that occurs despite the use of anticonvulsants that have otherwise successfully prevented seizures in the patient.[50]: 456 Breakthrough seizures may be more dangerous than non-breakthrough seizures because they are unexpected by the patient, who may have considered themselves free from seizures and, therefore, not take any precautions.[51] Breakthrough seizures are more likely with a number of triggers.[52]: 57 Often when a breakthrough seizure occurs in a person whose seizures have always been well controlled, there is a new underlying cause to the seizure.[53]

Breakthrough seizures vary. Studies have shown the rates of breakthrough seizures ranging from 11 to 37%.[54] Treatment involves measuring the level of the anticonvulsant in the patient's system and may include increasing the dosage of the existing medication, adding another medication to the existing one, or altogether switching medications.[55] A person with a breakthrough seizure may require hospitalization for observation.[50]: 498

Other

- Acute illness: Some illnesses caused by viruses or bacteria may lead to a seizure, especially when vomiting or diarrhea occur, as this may reduce the absorption of the anticonvulsant.[52]: 67

- Malnutrition: May be the result of poor dietary habits, lack of access to proper nourishment, or fasting.[52]: 68 In seizures that are controlled by diet in children, a child may break from the diet on their own.[56]

Music (as in musicogenic epilepsy) [57][58][59]

Diagnosis and management

In the case of patients with seizures associated with medical illness, the patients are firstly stabilized. They are attended to their circulation, airway, and breathing. Next vital signs are assessed through a monitor, intravenous access is obtained, and concerning laboratory tests are performed. Phenytoin or fosphenytoin supplemented with benzodiazepines are administered as the first line of therapy if the seizure persists for more than 5 –10 minutes. Through neuroimaging, clinical assessments, and spinal-fluid examination the patients are screened for intrinsic neurological anomalies. The patients are analyzed for non-epileptic seizures. Early electroencephalography is recommended if there is a possibility of non-convulsive or subtle status epilepticus. They are examined for disorders such as sarcoidosis, porphyria, and other unusual systemic disorders. Information is gathered on the drug, medication history, and its withdrawal. For seizures associated with alcohol, intravenous pyridoxine and other specific antidotes are prescribed. The patient is checked for proconvulsant exposure. All underlying potential causes are considered. For instance, in a patient with an end-stage renal disease where there is a probability of hypertensive encephalopathy, blood pressure is analyzed.[2]

References

- Delanty, Norman; Vaughan, Carl J.; French, Jacqueline A. (1998-08-01). "Medical causes of seizures". The Lancet. 352 (9125): 383–390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02158-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 9717943. S2CID 42324759.

- Delanty, Norman; Vaughan, Carl J; French, Jacqueline A (1998-08-01). "Medical causes of seizures". The Lancet. 352 (9125): 383–390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02158-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 9717943. S2CID 42324759.

- "Epilepsy Foundation".

- Jonathan H. Pincus; Gary J. Tucker (27 September 2002). Behavioral Neurology. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-803152-9.

- 100 Questions & Answers About Epilepsy, Anuradha Singh, page 79

- Keyser, A.; De Bruijn, S.F.T.M. (1991). "Epileptic Manifestations and Vitamin B1Deficiency". European Neurology. 31 (3): 121–5. doi:10.1159/000116660. PMID 2044623.

- Fattal-Valevski, A.; Bloch-Mimouni, A.; Kivity, S.; Heyman, E.; Brezner, A.; Strausberg, R.; Inbar, D.; Kramer, U.; Goldberg-Stern, H. (2009). "Epilepsy in children with infantile thiamine deficiency". Neurology. 73 (11): 828–33. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b121f5. PMID 19571254. S2CID 16976274.

- Vitamin B-6 Dependency Syndromes at eMedicine

- Matsumoto, Arifumi; Shiga, Yusei; Shimizu, Hiroshi; Kimura, Itaru; Hisanaga, Kinya (2009). "Encephalomyelopathy due to vitamin B12 deficiency with seizures as a predominant symptom". Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 49 (4): 179–85. doi:10.5692/clinicalneurol.49.179. PMID 19462816.

- Kumar, S (2004). "Recurrent seizures: an unusual manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency". Neurology India. 52 (1): 122–3. PMID 15069260.

- Mustafa TAŞKESEN; Ahmet YARAMIŞ; Selahattin KATAR; Ayfer GÖZÜ PİRİNÇÇİOĞLU; Murat SÖKER (2011). "Neurological presentations of nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency in 42 breastfed infants in Southeast Turkey" (PDF). Turk J Med Sci. TÜBİTAK. 41 (6): 1091–1096. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- Yavuz, Halûk (2008). "Vitamin B12 deficiency and seizures". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 50 (9): 720. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03083.x. PMID 18754925. S2CID 9565203.

- Morrell, Martha J. (2002). "Folic Acid and Epilepsy". Epilepsy Currents. 2 (2): 31–34. doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2002.00017.x. PMC 320966. PMID 15309159.

- Devinsky, Orrin; Schachter, Steven; Pacia, Steven (2005). Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. New York, N.Y.: Demos Medical Pub. ISBN 9781888799897.

- Engel, Jerome; Pedley, Timothy A.; Aicardi, Jean (2008). Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-7817-5777-5.

- Wilner, Andrew N. (1 November 2000). Epilepsy in Clinical Practice: A Case Study Approach. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-1-888799-34-7.

- "Epilepsy Foundation".

- Wilner, Andrew N. (1 November 2000). Epilepsy in Clinical Practice: A Case Study Approach. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-888799-34-7.

- Orrin Devinsky (1 January 2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- Orrin Devinsky (1 January 2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- Steven S. Agabegi; Elizabeth D. Agabegi (2008). Step-up to medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

missed doseseizure.

- Crain, Ellen F.; Gershel, Jeffrey C. (2003). Clinical manual of emergency pediatrics (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 9780071377508.

- Singh, Anuradha (2009). 100 Questions & Answers About Your Child's Epilepsy. 100 Questions & Answers. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett. p. 120. ISBN 9780763755218.

- MacDonald, J. T. (December 1987). "Breakthrough seizure following substitution of Depakene capsules (Abbott) with a generic product". Neurology. 37 (12): 1885. doi:10.1212/wnl.37.12.1885. PMID 3120036. S2CID 44324824.

- Greenberg, David A.; Michael J. Aminoff; Roger P. Simon (2012). "12". Clinical neurology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0071759052.

- Graves, RC; Oehler, K; Tingle, LE (Jan 15, 2012). "Febrile seizures: risks, evaluation, and prognosis". American Family Physician. 85 (2): 149–53. PMID 22335215.

- Orrin Devinsky (1 January 2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- Thomas R. Browne; Gregory L. Holmes (2008). Handbook of Epilepsy. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7817-7397-3.

- Graham F A Harding; Peter M Jeavons (10 January 1994). Photosensitive Epilepsy. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-898683-02-5.

- "Flickering light and seizurs". Pediatrics for Parents. March 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09 – via FindArticles.

- Wallace, Sheila J.; Farrell, Kevin (2004). Epilepsy in Children, 2E. CRC Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780340808146.

- Overview of Head Injuries: Head Injuries Merck Manual Home Edition

- Diane Roberts Stoler (1998). Coping with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Penguin. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-89529-791-4.

- Donald W. Marion (1999). Traumatic Brain Injury. Thieme. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-86577-727-9.

- "Head Injury as a Cause of Epilepsy". EpilepsyFoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2011-06-23. Epilepsy Foundation

- Stafstrom, Carl E. (July 2003). "Hyperglycemia Lowers Seizure Threshold". Epilepsy Currents. 3 (4): 148–149. doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2003.03415.x. ISSN 1535-7597. PMC 387262. PMID 15309063.

- Varghese, Precil; Gleason, Vanessa; Sorokin, Rachel; Senholzi, Craig; Jabbour, Serge; Gottlieb, Jonathan E. (2007). "Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients treated with antihyperglycemic agents". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2 (4): 234–240. doi:10.1002/jhm.212. ISSN 1553-5592. PMID 17702035.

- Falip, Mercè; Miró, Júlia; Carreño, Mar; Jaraba, Sònia; Becerra, Juan Luís; Cayuela, Núria; Perez Maraver, Manuel; Graus, Francesc (2014-11-15). "Hypoglycemic seizures and epilepsy in type I diabetes mellitus". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 346 (1): 307–309. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.08.024. ISSN 0022-510X. PMID 25183236. S2CID 7207035.

- "Can sleep deprivation trigger a seizure?". epilepsy.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

- Orrin Devinsky (1 January 2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- Ilo E. Leppik, MD (24 October 2006). Epilepsy: A Guide to Balancing Your Life. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-932603-20-0.

- Orrin Devinsky (1 January 2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- Candiotti, Keith A.; Lamas, Ana M. (1993). "Adverse neurologic reactions to the sting of the imported fire ant". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 102 (4): 417–420. doi:10.1159/000236592. PMID 8241804.

- Gonzalo Garijo, M.A.; Bobadilla González, P.; Puyana Ruiz, J. (1995). "Epileptic attacks associated with wasp sting-induced anaphylaxis". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 6 (4): 277–279. PMID 8844507.

- Moyano, Luz M.; Saito, Mayuko; Montano, Silvia M.; Gonzalvez, Guillermo; Olaya, Sandra; Ayvar, Viterbo; González, Isidro; Larrauri, Luis; Tsang, Victor C. W.; Llanos, Fernando; Rodríguez, Silvia (2014-02-13). "Neurocysticercosis as a Cause of Epilepsy and Seizures in Two Community-Based Studies in a Cysticercosis-Endemic Region in Peru". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (2): e2692. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002692. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 3923674. PMID 24551255.

- Nakken, Karl O.; Solaas, Marit H.; Kjeldsen, Marianne J.; Friis, Mogens L.; Pellock, John M.; Corey, Linda A. (2005). "Which seizure-precipitating factors do patients with epilepsy most frequently report?". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (1): 85–89. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.003. PMID 15652738. S2CID 36696690.

- Haut, Sheryl R.; Hall, Charles B.; Masur, Jonathan; Lipton, Richard B. (2007-11-13). "Seizure occurrence: precipitants and prediction". Neurology. 69 (20): 1905–1910. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000278112.48285.84. ISSN 1526-632X. PMID 17998482. S2CID 27433395.

- Gunn, B.G.; Baram, T.Z. (2017). "Stress and Seizures: Space, Time and Hippocampal Circuits". Trends in Neurosciences. 40 (11): 667–679. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.08.004. PMC 5660662. PMID 28916130.

- Jones, Jeffrey M. (2000). "'The Falling Sickness' in Literature". Southern Medical Journal. 93 (12): 1169–72. doi:10.1097/00007611-200012000-00006. PMID 11142451. S2CID 31281356.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2006). Emergency care and transportation of the sick and injured (9th ed.). Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett. pp. 456, 498. ISBN 9780763744052.

- Ettinger, Alan B.; Adiga, Radhika K. (2008). "Breakthrough Seizures—Approach to Prevention and Diagnosis". US Neurology. 4 (1): 40–42. doi:10.17925/USN.2008.04.01.40.

- Devinsky, Orrin (2008). Epilepsy: Patient and Family Guide (3rd ed.). New York: Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 57–68. ISBN 9781932603415.

- Lynn, D. Joanne; Newton, Herbert B.; Rae-Grant, Alexander D. (2004). The 5-Minute Neurology Consult. LWW medical book collection. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 191. ISBN 9780683307238.

- Pellock, John M.; Bourgeois, Blaise F.D.; Dodson, W. Edwin; Nordli Jr., Douglas R.; Sankar, Raman (2008). Pediatric Epilepsy: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Demos Medicical Series (3rd ed.). New York: Demos Medical Publishing. p. 287. ISBN 9781933864167.

- Engel Jr., Jerome; Pedley, Timothy A.; Aicardi, Jean (2008). Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781757775.

- Freeman, John M.; Kossoff, Eric; Kelly, Millicent (2006). Ketogenic Diets: Treatments for Epilepsy. Demos Health Series (4th ed.). New York: Demos. p. 54. ISBN 9781932603187.

- Stern, John (2015). "Musicogenic epilepsy". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 129: 469–477. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00026-3. ISBN 9780444626301. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 25726285.

- "music and epilepsy". Epilepsy Society. 2015-08-10. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- Maguire, Melissa Jane (21 May 2012). "Music and epilepsy: a critical review". Epilepsia. 53 (6): 947–61. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03523.x. PMID 22612325. S2CID 33600372.