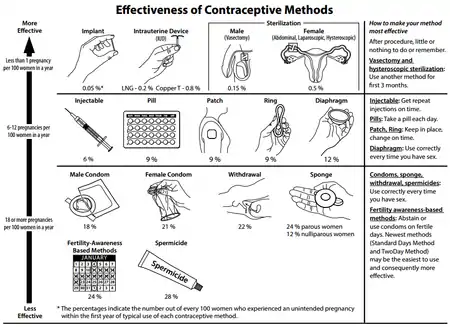

Comparison of birth control methods

There are many methods of birth control (also known as contraception). They vary in what is required of the user, side effects, and effectiveness. No method of birth control is ideal for every user. Outlined here are the different types of barrier methods, hormonal methods, various methods including spermicides, emergency contraceptives, and surgical methods.[1]

Methods

Hormonal methods

The IUD (intrauterine device) is a 'T' shaped device that is inserted into the uterus by a trained medical professional. There are two different types of IUDs, a copper or a hormonal IUD.[1] The copper IUD (also known as a copper T intrauterine device) is a non-hormonal option of birth control, the IUD is wrapped in copper which creates a toxic environment for sperm and eggs, thus preventing pregnancy.[2] The failure rate of a copper IUD is approximately 0.8% and can prevent pregnancy for up to 10 years. The hormonal IUD (also known as levonorgestrel intrauterine system or LNG UID) releases a small amount of the hormone called progestin that can prevent pregnancy for 3–6 years with a failure rate of 0.1-0.4%.[1] IUDs can be removed by a trained medical professional at anytime before the expiration date to allow for pregnancy.[3]

Oral contraceptives are another option, these are commonly known as 'the pill'. These are prescribed by a doctor and must be taken at the same time everyday in order to be the most effective. There are two different options, there is a combined pill option that contains both of the hormones estrogen and progestin. The other option is a progestin only pill. The failure rate of both of these oral contraceptives is 7%.[1]

Some choose to get an injection or a shot in order to prevent pregnancy. This is an option where a medical professional will inject the hormone progestin into a woman's arm or buttocks every 3 months to prevent pregnancy. The failure rate is 4%.[1]

Women can also get an implant into their upper arm that releases small amounts of hormones to prevent pregnancy. The implant is a thin rod shaped device that contains the hormone progestin that is inserted into the upper arm and can prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years. The failure rate is 0.1%.[1]

The patch is another simple option, it is a skin patch containing the hormones progestin and estrogen that is absorbed into the blood stream preventing pregnancy. The patch is typically worn on the lower abdomen and replaced once a week. The failure rate is 7%.[1]

The hormonal vaginal contraceptive ring is a ring that contains the hormones progestin and estrogen that a woman inserts into the vagina. It is replaced once a month and has a failure rate of 7%.[1]

Barrier methods

The diaphragm or cervical cap is used to prevent sperm from entering the uterus. It is a small shallow cup like cap that is inserted into the vagina with spermicide to cover the cervix and block sperm from entering the uterus. It is inserted before sex and comes in different sizes with a failure rate of 17%.[1]

A sponge can also be used as a contraceptive method, the contraceptive sponge contains spermicide and is inserted into the vagina and placed over the cervix to prevent sperm from entering the uterus. The sponge must be kept in place 6 hours after intercourse and can be removed and discarded. The failure rate for women who have had a baby before is 27% and those who have not had a baby, the failure rate is 14%.[1]

The male condom is typically made of latex (but other materials are available due to some people's allergies such as lambskin), the male condom is placed over the male's penis and prevents the sperm from getting into their partner's body. It can prevent pregnancy, STDs, and HIV if used appropriately. Male condoms can only be used once and are easily accessible at local stores. The failure rate is 13%.[1]

The female condom is worn by the woman, it is inserted into the vagina and prevents the sperm from entering her body. It can help prevent STDs and can be inserted up to 8 hours before intercourse. The failure rate is 21%.[1]

Other methods

Spermicides come in various forms such as: gels, foams, creams, film, suppositories, or tablets. The spermicides create an environment in which sperm can no longer live, they are typically used in addition to the male condom, diaphragm or cervical cap. They can be used by themselves by putting it into the vagina no more than an hour before intercourse and kept inside the vagina for 6–8 hours after intercourse. The failure rate is 21%.[1]

The fertility awareness-based method is when a woman who has a predictable and consistent menstrual cycle tracks the days that she is fertile. The typical woman has approximately 9 fertile days a month and either avoids intercourse on those days or uses an alternative birth control method for that period of time. The failure rate is between 2-23%.[1]

Lactational Amenorrhea (LAM) is an option for women who have had a baby within the past 6 months and are breastfeeding . This method is only successful if it has been less than 6 months since the birth of the baby, they must be fully breastfeeding their baby, and not having any periods.[1] The method is almost as effective as an oral contraceptive if the 3 conditions are strictly followed.[4]

The 'pull out method' or coitus interruptus is a method where the male will remove his penis from the vagina before ejaculating, this prevents sperm from reaching the egg and can prevent pregnancy. This method has to be done correctly every time and best if used in addition to other forms of birth control in order to prevent pregnancy. It has a failure rate of approximately 22%.[5]

Emergency contraceptives

A copper IUD can be used as an emergency contraceptive as long as it is inserted within 5 days of intercourse.[1]

There are two different types of emergency contraceptive pills, one contains ulipristal acetate and can prevent pregnancy if taken within 5 days of intercourse. The other contains levonorgestrel and can prevent pregnancy if taken with 3 days of intercourse. This option can be used if other birth control methods fail.[6]

Surgical methods

Tubal ligation is also known as 'tying tubes', this is the surgical process that a medical professional performs. This is done by closing or tying the fallopian tubes in order to prevent sperm from reaching the eggs. This is often done as an outpatient surgical procedure and is effective immediately after it is performed. The failure rate is 0.5%.[1]

A vasectomy is a minor surgical procedure where a doctor will cut the vas deferens and seal the ends to prevent sperm from reaching the penis and ultimately the egg. The method is usually successful after 12 weeks post procedure or until the sperm count is zero. Failure rate is 0.15%.[1]

User dependence

Different methods require different levels of diligence by users. Methods with little or nothing to do or remember, or that require a clinic visit less than once per year are said to be non-user dependent, forgettable or top-tier methods.[7] Intrauterine methods, implants and sterilization fall into this category.[7] For methods that are not user dependent, the actual and perfect-use failure rates are very similar.

Many hormonal methods of birth control, and LAM require a moderate level of thoughtfulness. For many hormonal methods, clinic visits must be made every three months to a year to renew the prescription. The pill must be taken every day, the patch must be reapplied weekly, or the ring must be replaced monthly. Injections are required every 12 weeks. The rules for LAM must be followed every day. Both LAM and hormonal methods provide a reduced level of protection against pregnancy if they are occasionally used incorrectly (rarely going longer than 4–6 hours between breastfeeds, a late pill or injection, or forgetting to replace a patch or ring on time). The actual failure rates for LAM and hormonal methods are somewhat higher than the perfect-use failure rates.

Higher levels of user commitment are required for other methods.[8] Barrier methods, coitus interruptus, and spermicides must be used at every act of intercourse. Fertility awareness-based methods may require daily tracking of the menstrual cycle. The actual failure rates for these methods may be much higher than the perfect-use failure rates.[9]

Side effects

Different forms of birth control have different potential side effects. Not all, or even most, users will experience side effects from a method.

The less effective the method, the greater the risk of the side-effects associated with pregnancy.

Minimal or no other side effects are possible with coitus interruptus, fertility awareness-based, and LAM. Some forms of periodic abstinence encourage examination of the cervix; insertion of the fingers into the vagina to perform this examination may cause changes in the vaginal environment. Following the rules for LAM may delay a woman's first post-partum menstruation beyond what would be expected from different breastfeeding practices.

Barrier methods have a risk of allergic reaction. Users sensitive to latex may use barriers made of less allergenic materials - polyurethane condoms, or silicone diaphragms, for example. Barrier methods are also often combined with spermicides, which have possible side effects of genital irritation, vaginal infection, and urinary tract infection.

Sterilization procedures are generally considered to have a low risk of side effects, though some persons and organizations disagree.[10][11] Female sterilization is a more significant operation than vasectomy, and has greater risks; in industrialized nations, mortality is 4 per 100,000 tubal ligations, versus 0.1 per 100,000 vasectomies.[12]

After IUD insertion, users may experience irregular periods in the first 3–6 months with Mirena, and sometimes heavier periods and worse menstrual cramps with ParaGard. However, continuation rates are much higher with IUDs compared to non-long-acting methods.[13] A positive characteristic of IUDs is that fertility and the ability to become pregnant returns quickly once the IUD is removed.[14]

Because of their systemic nature, hormonal methods have the largest number of possible side effects.[15]

Combined hormonal contraceptives contain estrogen and progestin hormones.[16] They can come in formulations such as a pills, vaginal rings, and transdermal patches.[16] Most people who use combined hormonal contraception experience breakthrough bleeding within the first 3 months.[16] Other common side effects include headaches, breast tenderness, and changes in mood.[17] Side effects from hormonal contraceptives typically disappear over time (3-5 months) with consistent use.[17] Less common effects of combined hormonal contraceptives include increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis to 2 to 10 per 10 000 women per year and venous thrombotic events (see venous thrombosis) to 7 to 10 per 10,000 women per year.[16]

Hormonal contraceptives can come in multiple forms including injectables. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), a progestin only injectable, has been found to cause amenorrhea; however, the irregular bleeding pattern returns to normal over time.[16][17] DMPA has also been associated with weight gain.[17] Other side effects more commonly associated with progestin-only products include acne and hirsutism.[17] Compared to combined hormonal contraceptives, progestin-only contraceptives typically produce a more regular bleeding pattern.[16]

Sexually transmitted disease prevention

Male and female condoms provide significant protection against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) when used consistently and correctly. They also provide some protection against cervical cancer.[18][19] Condoms are often recommended as an adjunct to more effective birth control methods (such as IUD) in situations where STD protection is also desired.[20]

Other barrier methods, such as diaphragm may provide limited protection against infections in the upper genital tract. Other methods provide little or no protection against sexually transmitted diseases.

Effectiveness calculation

Failure rates may be calculated by either the Pearl Index or a life table method. A "perfect-use" rate is where any rules of the method are rigorously followed, and (if applicable) the method is used at every act of intercourse.

Actual failure rates are higher than perfect-use rates for a variety of reasons:

- mistakes on the part of those providing instructions on how to use the method

- mistakes on the part of the method's users

- conscious user non-compliance with the method.

- insurance providers sometimes impede access to medications (e.g. require prescription refills monthly)[21]

For instance, someone using oral forms of hormonal birth control might be given incorrect information by a health care provider as to the frequency of intake, or for some reason not take the pill one or several days, or not go to the pharmacy on time to renew the prescription, or the pharmacy might be unwilling to provide enough pills to cover an extended absence.

Effectiveness

The table below color codes the typical-use and perfect-use failure rates, where the failure rate is measured as the expected number of pregnancies per year per woman using the method:

Blue under 1% lower risk Green up to 5% Yellow up to 10% Orange up to 20% Red over 20% higher risk Grey no data no data available

For example, a failure rate of 20% means that 20 of 100 women become pregnant during the first year of use. Note that the rate may go above 100% if all women, on average, become pregnant within less than a year. In the degenerated case of all women becoming pregnant instantly, the rate would be infinite.

In the user action required column, items that are non-user dependent (require action once per year or less) also have a blue background.

Some methods may be used simultaneously for higher effectiveness rates. For example, using condoms with spermicides the estimated perfect use failure rate would be comparable to the perfect use failure rate of the implant.[7] However, mathematically combining the rates to estimate the effectiveness of combined methods can be inaccurate, as the effectiveness of each method is not necessarily independent, except in the perfect case.[22]

If a method is known or suspected to have been ineffective, such as a condom breaking, or a method could not be used, as is the case for rape when user action is required for every act of intercourse, emergency contraception (ECP) may be taken up to 72 to 120 hours after sexual intercourse. Emergency contraception should be taken shortly before or as soon after intercourse as possible, as its efficacy decreases with increasing delay. Although ECP is considered an emergency measure, levonorgestrel ECP taken shortly before sex may be used as a primary method for woman who have sex only a few times a year and want a hormonal method, but don’t want to take hormones all the time.[23] Failure rate of repeated or regular use of LNG ECP is similar to rate for those using a barrier method.[24]

This table lists the rate of pregnancy during the first year of use.

| Birth control method | Brand/common name | Typical-use failure rate (%) | Perfect-use failure rate (%) | Type | Implementation | User action required |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptive implant | Implanon/Nexplanon,[25] Jadelle,[26] the implant | 0.05 (1 of 2000) | 0.05 | Progestogen | Subdermal implant | 3-5 years |

| Vasectomy[25] | male sterilization | 0.15 (1 of 666) | 0.1 | Sterilization | Surgical procedure | Once |

| Combined injectable[27] | Lunelle, Cyclofem | 0.2 (1 of 500) | 0.2 | Estrogen + progestogen | Injection | Monthly |

| IUD with progestogen[25] | Mirena, Skyla, Liletta | 0.2 (1 of 500) | 0.2 | Intrauterine & progestogen | Intrauterine | 3-7 years |

| Essure (removed from markets)[28] | female sterilization | 0.26 (1 of 384) | 0.26 | Sterilization | Surgical procedure | Once |

| Tubal ligation[25] | Tube tying, female sterilization | 0.5 (1 of 200) | 0.5 | Sterilization | Surgical procedure | Once |

| Bilateral salpingectomy[29] | Tube removal, "bisalp" | 0.75 (1 of 133) after 10 years[note 1] | 0.75 after 10 years | Sterilization | Surgical procedure | Once |

| IUD with copper[25] | Paragard, Copper T, the coil | 0.8 (1 of 125) | 0.6 | Intrauterine & copper | Intrauterine | 3 to 12+ years |

| Forschungsgruppe NFP symptothermal method, teaching sessions + application[25][30] | Sensiplan by Arbeitsgruppe NFP (Malteser Germany gGmbh) | 1.68 (1 of 60) | 0.43 (1 of 233) | Behavioral | Teaching sessions, observation, charting and evaluating a combination of fertility symptoms | Three teaching sessions + daily application |

| LAM for 6 months only; not applicable if menstruation resumes[31][note 2] | ecological breastfeeding | 2 (1 of 50) | 0.5 | Behavioral | Breastfeeding | Every few hours |

| 2002[32] cervical cap and spermicide (discontinued in 2008) used by nulliparous[33][note 3][note 4] | Lea's Shield | 5 (1 of 20) | no data | Barrier + spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| MPA shot[34] | Depo Provera, the shot | 4 (1 of 25) | 0.2 | Progestogen | Injection | 12 weeks |

| Testosterone injection for male (unapproved, experimental method)[35] | Testosterone Undecanoate | 6.1 (1 of 16) | 1.1 | Testosterone | Intramuscular Injection | Every 4 weeks |

| 1999 cervical cap and spermicide (replaced by second generation in 2003)[36] | FemCap | 7.6 (estimated) (1 of 13) | no data | Barrier & spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| Contraceptive patch[34] | Ortho Evra, the patch | 7 (1 of 14) | 0.3 | Estrogen & progestogen | Transdermal patch | Weekly |

| Combined oral contraceptive pill[37] | the Pill | 7 (1 of 14)[38] | 0.3 | Estrogen & progestogen + Placebo[39] | Oral medication | Daily |

| Ethinylestradiol/etonogestrel vaginal ring[34] | NuvaRing, the ring | 7 (1 of 14) | 0.3 | Estrogen & progestogen | Vaginal insertion | In place 3 weeks / 1 week break |

| Progestogen only pill[25] | POP, minipill | 9[38] | 0.3 | Progestogen[39] | Oral medication | Daily |

| Ormeloxifene[40] | Saheli, Centron | 9 | 2 | SERM | Oral medication | Weekly |

| Emergency contraception pill | Plan B One-Step® | no data | no data | Levonorgestrel | Oral medication | Every act of intercourse |

| Standard Days Method[25] | CycleBeads, iCycleBeads | 12 (1 of 8.3) | 5 | Behavioral | Counting days since menstruation | Daily |

| Diaphragm and spermicide[25] | 12 (1 of 6) | 6 | Barrier & spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse | |

| Plastic contraceptive sponge with spermicide used by nulliparous[34][note 4] | Today sponge, the sponge | 14 | 9 | Barrier & spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| 2002[32] cervical cap and spermicide (discontinued in 2008) used by parous[33][note 3][note 5] | Lea's Shield | 15 (1 of 6) | no data | Barrier + spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| 1988 cervical cap and spermicide (discontinued in 2005) used by nulliparous[note 4] | Prentif | 16 | 9 | Barrier + spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| Male latex condom[34] | Condom | 13 (1 of 7) | 2 | Barrier | Placed on erect penis | Every act of intercourse |

| Female condom[25] | 21 (1 of 4.7) | 5 | Barrier | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse | |

| Coitus interruptus[34] | withdrawal method, pulling out | 20 (1 of 5)[41] | 4 | Behavioral | Withdrawal | Every act of intercourse |

| Symptoms-based fertility awareness ex. symptothermal and calendar-based methods[34][note 6][note 7] | TwoDay method, Billings ovulation method, Creighton Model | 24 (1 of 4) | 0.40–4 | Behavioral | Observation and charting of basal body temperature, cervical mucus or cervical position | |

| Calendar-based methods[25] | the rhythm method, Knaus-Ogino method, Standard Days method | no data | 5 | Behavioral | Calendar-based | Daily |

| Plastic contraceptive sponge with spermicide used by parous[34][note 5] | Today sponge, the sponge | 27 (1 of 3.7) | 20 | Barrier & spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| Spermicidal gel, suppository, or film[34] | 21 (1 of 5) | 16 | Spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse | |

| 1988 cervical cap and spermicide (discontinued in 2005) used by parous[note 5] | Prentif | 32 | 26 | Barrier + spermicide | Vaginal insertion | Every act of intercourse |

| Abstinence pledge[note 8][42] | 50–57.5 (estimated) (1 of 2) | no data | Behavioral | Commitment | Once | |

| None (unprotected intercourse)[25] | 85 (6 of 7) | 85 | Behavioral | Discontinuing birth control | N/A | |

| Birth control method | Brand/common name | Typical-use failure rate (%) | Perfect-use failure rate (%) | Type | Implementation | User action required |

Table notes

- No data for 1 year failure rates

- The pregnancy rate applies until the user reaches six months postpartum, or until menstruation resumes, whichever comes first. If menstruation occurs earlier than six months postpartum, the method is no longer effective. For users for whom menstruation does not occur within the six months: after six months postpartum, the method becomes less effective.

- In the effectiveness study of Lea's Shield, 84% of participants were parous. The unadjusted pregnancy rate in the six-month study was 8.7% among spermicide users and 12.9% among non-spermicide users. No pregnancies occurred among nulliparous users of the Lea's Shield. Assuming the effectiveness ratio of nulliparous to parous users is the same for the Lea's Shield as for the Prentif cervical cap and the Today contraceptive sponge, the unadjusted six-month pregnancy rate would be 2.2% for spermicide users and 2.9% for those who used the device without spermicide.

- Nulliparous refers to those who have not given birth.

- Parous refers to those who have given birth.

- No formal studies meet the standards of Contraceptive Technology for determining typical effectiveness. The typical effectiveness listed here is from the CDC's National Survey of Family Growth, which grouped symptoms-based methods together with calendar-based methods. See Fertility awareness#Effectiveness.

- The term fertility awareness is sometimes used interchangeably with the term natural family planning (NFP), though NFP usually refers to use of periodic abstinence in accordance with Catholic beliefs.

- Strictly speaking, abstinence pledges are not a method of birth control, as their purpose is preservation of the virginity of unmarried girls, with prevention of pregnancies only being a side-effect. This also means that they are restricted to the time before marriage.

Table references

- "Contraception | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- "Copper IUD (ParaGard) - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- "Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)". Healthline. 2019-01-11. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- "Breastfeeding as Birth Control | Information About LAM". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- "What is the Effectiveness of the Pull Out Method?". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- "What Kind of Emergency Contraception Is Best For Me?". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, eds. (2011). Contraceptive Technology (20th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0.

- Shears KH, Aradhya KW (July 2008). Helping women understand contraceptive effectiveness (PDF) (Report). Family Health International.

- Trussell J (2007). "Contraceptive Efficacy". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL (eds.). Contraceptive Technology (19th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. ISBN 978-0-9664902-0-6.

- Bloomquist M (May 2000). "Getting Your Tubes Tied: Is this common procedure causing uncommon problems?". MedicineNet.com. WebMD. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Hauber KC. "If It Works, Don't Fix It!". Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Awsare NS, Krishnan J, Boustead GB, Hanbury DC, McNicholas TA (November 2005). "Complications of vasectomy". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 87 (6): 406–10. doi:10.1308/003588405X71054. PMC 1964127. PMID 16263006.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group (November 2017). "Practice Bulletin No. 186: Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine Devices". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 130 (5): e251–e269. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002400. ISSN 1873-233X. PMID 29064972. S2CID 35477591.

- "Planned Parenthood IUD Birth Control - Mirena IUD - ParaGard IUD". Retrieved 2012-02-26.

- Staff, Healthwise. "Advantages and Disadvantages of Hormonal Birth Control". Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- Teal, Stephanie; Edelman, Alison (2021-12-28). "Contraception Selection, Effectiveness, and Adverse Effects: A Review". JAMA. 326 (24): 2507–2518. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.21392. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 34962522. S2CID 245557522.

- Barr, Nancy Grossman (December 15, 2020). "Managing Adverse Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives" (PDF). American Family Physician. 82 (12): 1499–1506. PMID 21166370 – via American Academy of Family Physicians.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, O'Reilly S, Kiviat NB, Holmes KK, Koutsky LA (June 2006). "Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (25): 2645–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa053284. PMID 16790697.

- Hogewoning CJ, Bleeker MC, van den Brule AJ, Voorhorst FJ, Snijders PJ, Berkhof J, Westenend PJ, Meijer CJ (December 2003). "Condom use promotes regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and clearance of human papillomavirus: a randomized clinical trial". International Journal of Cancer. 107 (5): 811–6. doi:10.1002/ijc.11474. PMID 14566832.

- Cates W, Steiner MJ (March 2002). "Dual protection against unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections: what is the best contraceptive approach?". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 29 (3): 168–74. doi:10.1097/00007435-200203000-00007. PMID 11875378. S2CID 42792667.

- Trussell J, Wynn LL (January 2008). "Reducing unintended pregnancy in the United States". Contraception. 77 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.001. PMID 18082659.

- Kestelman P, Trussell J (1991). "Efficacy of the simultaneous use of condoms and spermicides". Family Planning Perspectives. 23 (5): 226–7, 232. doi:10.2307/2135759. JSTOR 2135759. PMID 1743276.

- Shelton JD (July 2002). "Repeat emergency contraception: facing our fears". Contraception. 66 (1): 15–7. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00313-X. PMID 12169375.

- "Efficacy and side effects of immediate postcoital levonorgestrel used repeatedly for contraception. United Nations Development Programme/ United Nations Population Fund/World Health Organization/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Task Force on Post-Ovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. vonhertzenh@who.ch". Contraception. 61 (5): 303–8. May 2000. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00116-5. PMID 10906500.

- Trussell J (May 2011). "Contraceptive failure in the United States". Contraception. 83 (5): 397–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. PMC 3638209. PMID 21477680.

- Sivin I, Campodonico I, Kiriwat O, Holma P, Diaz S, Wan L, Biswas A, Viegas O, et al. (December 1998). "The performance of levonorgestrel rod and Norplant contraceptive implants: a 5 year randomized study". Human Reproduction. 13 (12): 3371–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/13.12.3371. PMID 9886517.

- "FDA Approves Combined Monthly Injectable Contraceptive". The Contraception Report. Contraception Online. June 2001. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- "Essure System - P020014". United States Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Archived from the original on 2008-12-04.

- Castellano, Tara; Zerden, Matthew; Marsh, Laura; Boggess, Kim (November 2017). "Risks and Benefits of Salpingectomy at the Time of Sterilization". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 72 (11): 663–668. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000503. PMID 29164264.

- Frank-Herrmann P, Heil J, Gnoth C, Toledo E, Baur S, Pyper C, Jenetzky E, Strowitzki T, et al. (May 2007). "The effectiveness of a fertility awareness based method to avoid pregnancy in relation to a couple's sexual behaviour during the fertile time: a prospective longitudinal study". Human Reproduction. 22 (5): 1310–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem003. PMID 17314078.

- Trussell J (2007). "Contraceptive Efficacy". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL (eds.). Contraceptive Technology (19th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 773–845. ISBN 978-0-9664902-0-6.

- "FDA approves Leas Shield". Contraception Report. 13 (2). 1 June 2002. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Mauck C, Glover LH, Miller E, Allen S, Archer DF, Blumenthal P, Rosenzweig A, Dominik R, et al. (June 1996). "Lea's Shield: a study of the safety and efficacy of a new vaginal barrier contraceptive used with and without spermicide". Contraception. 53 (6): 329–35. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(96)00081-9. PMID 8773419.

- http://www.contraceptivetechnology.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Contraceptive-Failure-Rates.pdf

- Gu Y, Liang X, Wu W, Liu M, Song S, Cheng L, Bo L, Xiong C, Wang X, Liu X, Peng L, Yao K (June 2009). "Multicenter contraceptive efficacy trial of injectable testosterone undecanoate in Chinese men". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (6): 1910–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1846. PMID 19293262.

- "Clinician Protocol". FemCap manufacturer. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Trussell J (2011). "Contraceptive Efficacy." (PDF). In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Kowal D, Policar M (eds.). Contraceptive Technology (Twentieth Revised ed.). New York NY: Ardent Media. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2014-03-30.

- see Combined oral contraceptive pill § Role of Placebo Pills

- Puri V (1988). "Results of multicentric trial of Centchroman". In Dhwan B. N., et al. (eds.). Pharmacology for Health in Asia : Proceedings of Asian Congress of Pharmacology, 15–19 January 1985, New Delhi, India. Ahmedabad: Allied Publishers.

Nityanand S (1990). "Clinical evaluation of Centchroman: a new oral contraceptive". In Puri CP, Van Look PF (eds.). Hormone Antagonists for Fertility Regulation. Bombay: Indian Society for the Study of Reproduction and Fertility. - Jones RK, Fennell J, Higgins JA, Blanchard K (2009). "Better than nothing or savvy risk-reduction practice? The importance of withdrawal" (PDF). Contraception. 79 (6): 407–10. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.008. PMID 19442773.

- Corinna H (29 January 2010). "What's the Typical Use Effectiveness Rate of Abstinence?". Scarleteen.

Cost and cost-effectiveness

Family planning is among the most cost-effective of all health interventions.[1] Costs of contraceptives include method costs (including supplies, office visits, training), cost of method failure (ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, induced abortion, birth, child care expenses) and cost of side effects.[2] Contraception saves money by reducing unintended pregnancies and reducing transmission of sexually transmitted infections. By comparison, in the US, method related costs vary from nothing to about $1,000 for a year or more of reversible contraception.

During the initial five years, vasectomy is comparable in cost to the IUD. Vasectomy is much less expensive and safer than tubal ligation.

Since ecological breastfeeding and fertility awareness are behavioral they cost nothing or a small amount upfront for a thermometer and / or training. Fertility awareness based methods can be used throughout a woman's reproductive lifetime.

Not using contraceptives is the most expensive option. While in that case there are no method related costs, it has the highest failure rate, and thus the highest failure related costs. Even if one only considers medical costs relating to preconception care and birth, any method of contraception saves money compared to using no method.

The most effective and the most cost-effective methods are long-acting methods. Unfortunately these methods often have significant up-front costs, requiring the user to pay a portion of these costs prevents some from using more effective methods.[3] Contraception saves money for the public health system and insurers.[4]

References

- Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE (2010). "Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies". Epidemiologic Reviews. 32 (1): 152–74. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq012. PMC 3115338. PMID 20570955.

- Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J (January 2009). "Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States". Contraception. 79 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. PMC 3638200. PMID 19041435.

- Cleland K, Peipert JF, Westhoff C, Spear S, Trussell J (May 2011). "Family planning as a cost-saving preventive health service". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (18): e37. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1104373. PMID 21506736.

- Jennifer J. Frost; Lawrence B. Finer; Athena Tapales (2008). "The Impact of Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinic Services on Unintended Pregnancies and Government Cost Savings". Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 19 (3): 778–796. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0060. ISSN 1548-6869. PMID 18677070. S2CID 14727184.