Pressure ulcer

Pressure ulcers, also known as pressure sores, bed sores or pressure injuries, are localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue that usually occur over a bony prominence as a result of usually long-term pressure, or pressure in combination with shear or friction. The most common sites are the skin overlying the sacrum, coccyx, heels, and hips, though other sites can be affected, such as the elbows, knees, ankles, back of shoulders, or the back of the cranium.

| Pressure ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Decubitus (plural: decubitūs), or decubitous ulcers, pressure injuries, pressure sores, bedsores |

| |

| Stage IV decubitus displaying the tuberosity of the ischium protruding through the tissue, and possible onset of osteomyelitis. | |

| Specialty | Plastic surgery |

| Complications | infection |

Pressure ulcers occur due to pressure applied to soft tissue resulting in completely or partially obstructed blood flow to the soft tissue. Shear is also a cause, as it can pull on blood vessels that feed the skin. Pressure ulcers most commonly develop in individuals who are not moving about, such as those who are on chronic bedrest or consistently use a wheelchair. It is widely believed that other factors can influence the tolerance of skin for pressure and shear, thereby increasing the risk of pressure ulcer development. These factors are protein-calorie malnutrition, microclimate (skin wetness caused by sweating or incontinence), diseases that reduce blood flow to the skin, such as arteriosclerosis, or diseases that reduce the sensation in the skin, such as paralysis or neuropathy. The healing of pressure ulcers may be slowed by the age of the person, medical conditions (such as arteriosclerosis, diabetes or infection), smoking or medications such as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Although often prevented and treatable if detected early, pressure ulcers can be very difficult to prevent in critically ill people, frail elders and individuals with impaired mobility such as wheelchair users (especially where spinal injury is involved). Primary prevention is to redistribute pressure by regularly turning the person. The benefit of turning to avoid further sores is well documented since at least the 19th century. In addition to turning and re-positioning the person in the bed or wheelchair, eating a balanced diet with adequate protein[1] and keeping the skin free from exposure to urine and stool is important.[2]

The rate of pressure ulcers in hospital settings is high; the prevalence in European hospitals ranges from 8.3% to 23%, and the prevalence was 26% in Canadian healthcare settings from 1990 to 2003.[3] In 2013, there were 29,000 documented deaths from pressure ulcers globally, up from 14,000 deaths in 1990.[4]

Presentation

Complications

Pressure ulcers can trigger other ailments, cause considerable suffering, and can be expensive to treat. Some complications include autonomic dysreflexia, bladder distension, bone infection, pyarthrosis, sepsis, amyloidosis, anemia, urethral fistula, gangrene and very rarely malignant transformation (Marjolin's ulcer - secondary carcinomas in chronic wounds). Sores may recur if those with pressure ulcers do not follow recommended treatment or may instead develop seromas, hematomas, infections, or wound dehiscence. Paralyzed individuals are the most likely to have pressure sores recur. In some cases, complications from pressure sores can be life-threatening. The most common causes of fatality stem from kidney failure and amyloidosis. Pressure ulcers are also painful, with individuals of all ages and all stages of pressure ulcers reporting pain.

Cause

There are four mechanisms that contribute to pressure ulcer development:[5]

- External (interface) pressure applied over an area of the body, especially over the bony prominences can result in obstruction of the blood capillaries, which deprives tissues of oxygen and nutrients, causing ischemia (deficiency of blood in a particular area), hypoxia (inadequate amount of oxygen available to the cells), edema, inflammation, and, finally, necrosis and ulcer formation. Ulcers due to external pressure occur over the sacrum and coccyx, followed by the trochanter and the calcaneus (heel).

- Friction is damaging to the superficial blood vessels directly under the skin. It occurs when two surfaces rub against each other. The skin over the elbows can be injured due to friction. The back can also be injured when patients are pulled or slid over bed sheets while being moved up in bed or transferred onto a stretcher.

- Shearing is a separation of the skin from underlying tissues. When a patient is partially sitting up in bed, their skin may stick to the sheet, making them susceptible to shearing in case underlying tissues move downward with the body toward the foot of the bed. This may also be possible on a patient who slides down while sitting in a chair.

- Moisture is also a common pressure ulcer culprit. Sweat, urine, feces, or excessive wound drainage can further exacerbate the damage done by pressure, friction, and shear. It can contribute to maceration of surrounding skin thus potentially expanding the deleterious effects of pressure ulcers.

Risk factors

There are over 100 risk factors for pressure ulcers.[6] Factors that may place a patient at risk include immobility, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, malnutrition, cerebral vascular accident and hypotension.[6][7] Other factors are age of 70 years and older, current smoking history, dry skin, low body mass index, urinary and fecal incontinence, physical restraints, malignancy, and history of pressure ulcers.

Pathophysiology

Pressure ulcers may be caused by inadequate blood supply and resulting reperfusion injury when blood re-enters tissue. A simple example of a mild pressure sore may be experienced by healthy individuals while sitting in the same position for extended periods of time: the dull ache experienced is indicative of impeded blood flow to affected areas. Within 2 hours, this shortage of blood supply, called ischemia, may lead to tissue damage and cell death. The sore will initially start as a red, painful area. The other process of pressure ulcer development is seen when pressure is high enough to damage the cell membrane of muscle cells. The muscle cells die as a result and skin fed through blood vessels coming through the muscle die. This is the deep tissue injury form of pressure ulcers and begins as purple intact skin.

According to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, pressure ulcers are one of the eight preventable iatrogenic illnesses. If a pressure ulcer is acquired in the hospital, the hospital will no longer receive reimbursement for the person's care. Hospitals spend about $5 billion annually for treatment of pressure ulcers.[8]

Sites

Common pressure sore sites include the skin over the ischial tuberosity, the sacrum, the heels of the feet, over the heads of the long bones of the foot, buttocks, over the shoulder, and over the back of the head.[9]

Biofilm

Biofilm is one of the most common reasons for delayed healing in pressure ulcers. Biofilm occurs rapidly in wounds and stalls healing by keeping the wound inflamed. Frequent debridement and antimicrobial dressings are needed to control the biofilm. Infection prevents healing of pressure ulcers. Signs of pressure ulcer infection include slow or delayed healing and pale granulation tissue. Signs and symptoms of systemic infection include fever, pain, redness, swelling, warmth of the area, and purulent discharge. Additionally, infected wounds may have a gangrenous smell, be discolored, and may eventually produce more pus.

In order to eliminate this problem, it is imperative to apply antiseptics at once. Hydrogen peroxide (a near-universal toxin) is not recommended for this task as it increases inflammation and impedes healing.[10] Dressings with cadexomer iodine, silver, or honey have been shown to penetrate bacterial biofilms. Systemic antibiotics are not recommended in treating local infection in a pressure ulcer, as it can lead to bacterial resistance. They are only recommended if there is evidence of advancing cellulitis, bony infection, or bacteria in the blood.[11]

Diagnosis

Classification

The definitions of the pressure ulcer stages are revised periodically by the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPUAP)[12] in the United States and the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) in Europe.[13] Different classification systems are used around the world, depending upon the health system, the health discipline and the purpose for the classifying (e.g. health care versus, prevalence studies versus funding.[14] Briefly, they are as follows:[15][16]

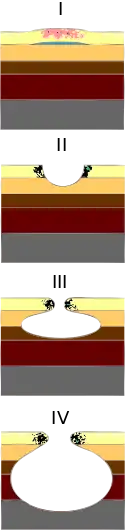

- Stage I: Intact skin with non-blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ from the surrounding area. The area differs in characteristics such as thickness and temperature as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1 may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. May indicate "at risk" persons (a heralding sign of risk).

- Stage II: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister. Presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising. This stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, perineal dermatitis, maceration or excoriation.

- Stage III: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of tissue loss. May include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage 3 pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and stage 3 ulcers can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep stage 3 pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable.

- Stage IV: Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed. Often include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage 4 pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and these ulcers can be shallow. Stage 4 ulcers can extend into muscle and/or supporting structures (e.g., fascia, tendon or joint capsule) making osteomyelitis likely to occur. Exposed bone/tendon is visible or directly palpable. In 2012, the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel stated that pressure ulcers with exposed cartilage are also classified as a stage 4.

- Unstageable: Full thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed. Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, cannot be determined. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance) eschar on the heels is normally protective and should not be removed.

- Suspected deep tissue injury: A purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. A deep tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Evolution may include a thin blister over a dark wound bed. The wound may further evolve and become covered by thin eschar. Evolution may be rapid exposing additional layers of tissue even with optimal treatment.

The term medical device related pressure ulcer refers to a cause rather than a classification. Pressure ulcers from a medical device are classified according to the same classification system being used for pressure ulcers arising from other causes, but the cause is usually noted.

Ischemic fasciitis

Ischemic fasciitis (IF) is a benign tumor in the class of fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors[17] that, like pressure ulcers, may develop in elderly, bed-ridden individuals.[18] These tumors commonly form in the subcutaneous tissues (i.e. lower most tissue layer of the skin) that overlie bony protuberances such as those in or around the hip, shoulder, greater trochanter of the femur, iliac crest, lumbar region, or scapular region.[19] IF tumors differ from pressure ulcers in that they typically do not have extensive ulcerations of the skin and on histopathological microscopic analysis lack evidence of acute inflammation as determined by the presence of various types of white blood cells.[20] These tumors are commonly treated by surgical removal.[21]

Prevention

In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Nursing has published guidelines in Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment and Prevention that call for identifying people at risk and taking preventive action;[22] the UK National Standards for Care Homes to do so as well.[23] Recent efforts in the United States and South Korea have sought to automate risk assessment and classification by training machine learning models on electronic health records.[24][25][26]

Internationally, the NPIAP, EPUAP and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance, together with wound organizations from 15 countries around the world, published updated the international evidence-based clinical practice guideline in 2019.[14] The 2019 guideline was developed by an international team of over 180 clinical specialists and updates the 2009 EPUAP/NPUAP clinical guideline and the 2014 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline. The guideline includes recommendations on strategies to treat pressure ulcers, including the use of bed rest, pressure redistributing support surfaces, nutritional support, repositioning, wound care (e.g. debridement, wound dressings) and biophysical agents (e.g. electrical stimulation).[27] Reliable scientific evidence to support the use of many of these interventions, though, is lacking. More research is needed to assess how to best support the treatment of pressure ulcers, for example by repositioning.[28][29][30][31] Also, the benefit of using systemic or topical antibiotics in the management of pressure ulcer is still unclear.[32]

It is important to understand that before turning and repositioning occur, a risk assessment tool is used to determine if the patient will need it. Some of the most common risk assessment tools are the Braden Scale, Norton, or Waterlow tools. The type of risk assessment tool that is used, will depend on which hospital the patient is admitted to and the location. After the risk assessment tool is used, a plan will be developed for the patient individually to prevent Hospital- Acquired Pressure Injuries. This plan will consist of different turning and repositioning strategies. These risk assessment tools provide the nursing staff with a baseline for each patient regarding their individual risk for acquiring a pressure injury. Factors that contribute to these risk assessment tools are moisture, activity, and mobility. These factors are considered and scored using the scale being used, whether it be the Braden, Norton, or Waterlow scale. The numbers are then added up and based on that final number, a score will be given and appropriate measures will be taken to ensure that the patient is being properly repositioned. Unfortunately, this is not always completed in hospitals like it should be.[33]

The most important care for a person at risk for pressure ulcers and those with bedsores is the redistribution of pressure so that no pressure is applied to the pressure ulcer.[34] In the 1940s Ludwig Guttmann introduced a program of turning paraplegics every two hours thus allowing bedsores to heal. Previously such individuals had a two-year life-expectancy, normally succumbing to blood and skin infections. Guttmann had learned the technique from the work of Boston physician Donald Munro.[35]

There is lack of evidence on prevention of pressure ulcer whether the patient is put in 30 degrees position or at the standard 90 degrees position.[36]

Nursing homes and hospitals usually set programs in place to avoid the development of pressure ulcers in those who are bedridden, such as using a routine time frame for turning and repositioning to reduce pressure. The frequency of turning and repositioning depends on the person's level of risk.

Support surfaces

A 2015 Cochrane systematic review found that people who lay on high specification or high density foam mattresses were 60% less likely to develop new pressure ulcers compared to regular foam mattresses. Sheepskin overlays on top of mattresses were also found to prevent new pressure ulcer formation. There is unclear research on the effectiveness of alternating pressure mattresses. Pressure-redistributive mattresses are used to reduce high values of pressure on prominent or bony areas of the body. There are several important terms used to describe how these support surfaces work. These terms were standardized through the Support Surface Standards Initiative of the NPUAP.[37] Many support surfaces redistribute pressure by immersing and/or enveloping the body into the surface. Some support surfaces, including antidecubitus mattresses and cushions, contain multiple air chambers that are alternately pumped.[38][39] Methods to standardize the products and evaluate the efficacy of these products have only been developed in recent years through the work of the S3I within NPUAP.[40] For individuals with paralysis, pressure shifting on a regular basis and using a wheelchair cushion featuring pressure relief components can help prevent pressure wounds.

A 2022 Cochrane systematic review aimed to find out how effective pressure redistributing static chairs (as opposed to wheelchairs) are for preventing pressure ulcers.[41] Static chairs can include: standard hospital chairs; chairs with no cushions or manual/dynamic function; and chairs with integrated pressure redistributing surfaces and recline, rise or tilt functions. The authors did not find any randomised controlled trials that were eligible for inclusion. More research is needed to establish how effective pressure redistributing static chairs are for preventing pressure ulcers.

Controlling the heat and moisture levels of the skin surface, known as skin microclimate management, also plays a significant role in the prevention and control of pressure ulcers.[42]

Nutrition

In addition, adequate intake of protein and calories is important. Vitamin C has been shown to reduce the risk of pressure ulcers. People with higher intakes of vitamin C have a lower frequency of bed sores in those who are bedridden than those with lower intakes. Maintaining proper nutrition in newborns is also important in preventing pressure ulcers. If unable to maintain proper nutrition through protein and calorie intake, it is advised to use supplements to support the proper nutrition levels.[43] Skin care is also important because damaged skin does not tolerate pressure. However, skin that is damaged by exposure to urine or stool is not considered a pressure ulcer. These skin wounds should be classified as Incontinence Associated Dermatitis.

Organisational changes

There is some suggestion that organisational changes may reduce incidence of pressure ulcers. Cochrane systematic reviews on organisation of health services,[44] risk assessment tools,[45] wound care teams,[46] and education[47][48] have concluded that evidence is uncertain as to the benefit of these organisational changes. This is largely due to the lack of high-quality research in these areas.

Other prevention therapies

A Cochrane systematic review found use of creams containing fatty acids may be more effective in reducing incidence of pressure ulcers compared to creams without fatty acids.[49] Silicone dressings may also reduce pressure ulcer incidence.[49] There is no evidence that massage reduces pressure ulcer incidence.[50]

Treatment

Internationally, the NPIAP, EPUAP and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance, together with wound organizations from 15 countries around the world published updated their international evidence-based clinical practice guideline in 2019.[27] The 2019 guideline was developed by an international team of over 180 clinical specialists and updates the 2009 EPUAP/NPUAP clinical guideline and the 2014 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline.[27] The guideline includes recommendations on strategies to treat pressure ulcers, including the use of bed rest, pressure redistributing support surfaces, nutritional support, repositioning, wound care (e.g. debridement, wound dressings) and biophysical agents (e.g. electrical stimulation).[27] Reliable scientific evidence to support the use of many of these interventions, though, is lacking. More research is needed to assess how to best support the treatment of pressure ulcers, for example by repositioning.[28][29][30][31] A 2020 Cochrane systematic review of randomized controlled trials concluded that more research is needed to determine whether or not electrical stimulation is an effective treatment for pressure ulcers.[51] In addition, the benefit of using systemic or topical antibiotics in the management of pressure ulcer is still unclear.[32]

Debridement

Necrotic tissue should be removed in most pressure ulcers. The heel is an exception in many cases when the limb has an inadequate blood supply. Necrotic tissue is an ideal area for bacterial growth, which has the ability to greatly compromise wound healing. There are five ways to remove necrotic tissue.

- Autolytic debridement is the use of moist dressings to promote autolysis with the body's own enzymes and white blood cells. It is a slow process, but mostly painless, and is most effective in individuals with a properly functioning immune system.

- Biological debridement, or maggot debridement therapy, is the use of medical maggots to feed on necrotic tissue and therefore clean the wound of excess bacteria. Although this fell out of favor for many years, in January 2004, the FDA approved maggots as a live medical device.[52]

- Chemical debridement, or enzymatic debridement, is the use of prescribed enzymes that promote the removal of necrotic tissue.

- Mechanical debridement, is the use of debriding dressings, whirlpool or ultrasound for slough in a stable wound.

- Surgical debridement, or sharp debridement, is the fastest method, as it allows a surgeon to quickly remove dead tissue.

Dressings

A 2017 Cochrane review found that it was unclear whether one topical agent or dressing was better than another for treating pressure ulcers. Protease-modulating dressings, foam dressings or collagenase ointment may be better at healing than gauze.[53] The wound dressing should be selected based on the wound and condition of the surrounding skin. There are some studies that indicate that antimicrobial products that stimulate the epithelization may improve the wound healing.[54] However, there is no international consensus on the selection of the dressings for pressure ulcers.[55] Cochrane reviews summarise evidence on alginate dressings,[56] foam dressings,[57] and hydrogel dressings.[58] Due to a lack of robust evidence, the benefits of these dressings over other treatments is unclear.

Some guidelines for dressing are:[59]

| Condition | Cover dressing |

|---|---|

| None to moderate exudates | Gauze with tape or composite |

| Moderate to heavy exudates | Foam dressing with tape or composite |

| Frequent soiling | Hydrocolloid dressing, film or composite |

| Fragile skin | Stretch gauze or stretch net |

Other treatments

Other treatments include anabolic steroids,[60] negative pressure wound therapy,[61] phototherapy,[62] support surfaces,[63] reconstructive surgery,[64] ultrasound,[65] topical phenytoin[66] and pressure relieving devices.[67] There is little or no evidence to support or refute the benefits of most of these treatments compared to each other and placebo. When selecting treatments, consideration should be given to patients' quality of life as well as the interventions' ease of use, reliability, and cost.

Epidemiology

Pressure ulcers resulted in 29,000 deaths worldwide in 2013 up from 14,000 deaths in 1990.[4]

Each year, more than 2.5 million people in the United States develop pressure ulcers.[68] In acute care settings in the United States, the incidence of bedsores is 0.4% to 38%; within long-term care it is 2.2% to 23.9%, and in home care, it is 0% to 17%. Similarly, there is wide variation in prevalence: 10% to 18% in acute care, 2.3% to 28% in long-term care, and 0% to 29% in home care. There is a much higher rate of bedsores in intensive care units because of immunocompromised individuals, with 8% to 40% of those in the ICU developing bedsores.[69] However, pressure ulcer prevalence is highly dependent on the methodology used to collect the data. Using the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) methodology there are similar figures for pressure ulcers in acutely sick people in the hospital. There are differences across countries, but using this methodology, pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe was consistently high, from 8.3% (Italy) to 22.9% (Sweden).[70] A recent study in Jordan also showed a figure in this range.[71] Some research shows differences in pressure-ulcer detection among white and black residents in nursing homes.[72]

See also

- Perfusion—systemic biomechanics of blood delivery

References

- Saghaleini SH, Dehghan K, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Mahmoodpoor A, Ostadi Z (April 2018). "Pressure Ulcer and Nutrition". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 22 (4): 283–289. doi:10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_277_17. PMC 5930532. PMID 29743767.

- Park KH, Choi H (March 2016). "Prospective study on Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis and its Severity instrument for verifying its ability to predict the development of pressure ulcers in patients with fecal incontinence". International Wound Journal. 13 (Suppl 1): 20–25. doi:10.1111/iwj.12549. PMC 7949835. PMID 26847935.

- McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Dumville JC, Middleton V, Cullum N (September 2015). "Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD001735. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001735.pub5. PMC 7075275. PMID 26333288.

- Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. (GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators) (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Grey JE, Harding KG, Enoch S (February 2006). "Pressure ulcers". BMJ. 332 (7539): 472–75. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7539.472. PMC 1382548. PMID 16497764.

- Lyder CH (January 2003). "Pressure ulcer prevention and management". JAMA. 289 (2): 223–26. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.223. PMID 12517234. S2CID 29969042.

- Berlowitz DR, Wilking SV (November 1989). "Risk factors for pressure sores. A comparison of cross-sectional and cohort-derived data". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 37 (11): 1043–50. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb06918.x. PMID 2809051. S2CID 26013510.

- Ebersole & Hess' Toward Healthy Aging. Missouri: Mosby. 2012.

- Bhat S (2013). Srb's Manual of Surgery (4 ed.). Jaypee Brother Medical Pub. p. 21. ISBN 9789350259443.

- "Dealing with Pressure Sores | Pressure Care". Airospring.

- Bluestein D, Javaheri A (November 2008). "Pressure ulcers: prevention, evaluation, and management". American Family Physician. 78 (10): 1186–1194. PMID 19035067. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP)".

- "European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel". EPUAP.

- Haesler E, et al. (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (U.S.), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance) (2019). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline (Third ed.). internationalguideline.com. ISBN 978-0-6480097-8-8.

- Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M (2016). "Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System". Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 43 (6): 585–97. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. PMC 5098472. PMID 27749790.

- Haesler E, et al. (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (U.S.), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance) (2014). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Quick reference guide (Second ed.). Perth, Western Australia. ISBN 9780957934368. OCLC 945954574.

- Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP (April 2021). "The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives". Pathologica. 113 (2): 70–84. doi:10.32074/1591-951X-213. PMC 8167394. PMID 33179614.

- Fukunaga M (September 2001). "Atypical decubital fibroplasia with unusual histology". APMIS. 109 (9): 631–35. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-185.x. PMID 11878717. S2CID 29499215.

- Montgomery EA, Meis JM, Mitchell MS, Enzinger FM (July 1992). "Atypical decubital fibroplasia. A distinctive fibroblastic pseudotumor occurring in debilitated patients". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 16 (7): 708–15. doi:10.1097/00000478-199207000-00009. PMID 1530110. S2CID 21116139.

- Liegl B, Fletcher CD (October 2008). "Ischemic fasciitis: analysis of 44 cases indicating an inconsistent association with immobility or debilitation". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 32 (10): 1546–52. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816be8db. PMID 18724246. S2CID 24664236.

- Sakamoto A, Arai R, Okamoto T, Yamada Y, Yamakado H, Matsuda S (October 2018). "Ischemic Fasciitis of the Left Buttock in a 40-Year-Old Woman with Beta-Propeller Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration (BPAN)". The American Journal of Case Reports. 19: 1249–52. doi:10.12659/AJCR.911300. PMC 6206622. PMID 30341275.

- Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment and Prevention: Recommendations (PDF). London: Royal College of Nursing. 2001. ISBN 1-873853-74-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Pressure Relief and Wound Care Archived 2013-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Independent Living (UK)

- Kaewprag P, Newton C, Vermillion B, Hyun S, Huang K, Machiraju R (July 2017). "Predictive models for pressure ulcers from intensive care unit electronic health records using Bayesian networks". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 17 (Suppl 2): 65. doi:10.1186/s12911-017-0471-z. PMC 5506589. PMID 28699545.

- Cramer EM, Seneviratne MG, Sharifi H, Ozturk A, Hernandez-Boussard T (September 2019). "Predicting the Incidence of Pressure Ulcers in the Intensive Care Unit Using Machine Learning". eGEMs. 7 (1): 49. doi:10.5334/egems.307. PMC 6729106. PMID 31534981.

- Cho I, Park I, Kim E, Lee E, Bates DW (November 2013). "Using EHR data to predict hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a prospective study of a Bayesian Network model". International Journal of Medical Informatics. 82 (11): 1059–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.06.012. PMID 23891086.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (2014). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide (PDF). Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-9579343-6-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Moore ZE, van Etten MT, Dumville JC (October 2016). "Bed rest for pressure ulcer healing in wheelchair users". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD011999. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011999.pub2. PMC 6457936. PMID 27748506.

- Langer G, Fink A (June 2014). "Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD003216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003216.pub2. PMID 24919719.

- Moore ZE, Cowman S (January 2015). "Repositioning for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD006898. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006898.pub4. PMC 7389249. PMID 25561248.

- Moore ZE, Cowman S (March 2013). "Wound cleansing for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004983. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004983.pub3. PMC 7389880. PMID 23543538.

- Norman G, Dumville JC, Moore ZE, Tanner J, Christie J, Goto S (April 2016). "Antibiotics and antiseptics for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (11): CD011586. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011586.pub2. PMC 6486293. PMID 27040598.

- Li Z, Marshall AP, Lin F, Ding Y, Chaboyer W (August 2022). "Pressure injury prevention practices among medical surgical nurses in a tertiary hospital: An observational and chart audit study". International Wound Journal. 19 (5): 1165–1179. doi:10.1111/iwj.13712. PMC 9284631. PMID 34729917.

- Reilly EF, Karakousis GC, Schrag SP, Stawicki SP (2007). "Pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit: The 'forgotten' enemy". OPUS 12 Scientist. 1 (2): 17–30.

- Whitteridge D (2004). "Guttmann, Sir Ludwig (1899–1980)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Gillespie BM, Walker RM, Latimer SL, Thalib L, Whitty JA, McInnes E, Chaboyer WP (June 2020). "Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD009958. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009958.pub3. PMC 7265629. PMID 32484259.

- See S3I at npuap.org

- Guy H (December 2004). "Preventing pressure ulcers: choosing a mattress". Professional Nurse. 20 (4): 43–46. PMID 15624622.

- "Antidecubitus Why?" (PDF). Antidecubitus Systems Matfresses Cushions. COMETE s.a.s. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- Bain DS, Ferguson-Pell M (2002). "Remote monitoring of sitting behavior of people with spinal cord injury". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 39 (4): 513–20. PMID 17638148.

- Stephens M, Bartley C, Dumville JC, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (February 2022). "Pressure redistributing static chairs for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (2): CD013644. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013644.pub2. PMC 8851035. PMID 35174477.

- "Hill-Rom Clinical Resource Center". Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- NICHQ. "How To Guide Pediatric Supplement – Preventing Pressure Ulcers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Joyce P, Moore ZE, Christie J (December 2018). "Organisation of health services for preventing and treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12): CD012132. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012132.pub2. PMC 6516850. PMID 30536917.

- Moore ZE, Patton D (January 2019). "Risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD006471. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006471.pub4. PMC 6354222. PMID 30702158.

- Moore ZE, Webster J, Samuriwo R (September 2015). "Wound-care teams for preventing and treating pressure ulcers" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD011011. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011011.pub2. PMC 8627699. PMID 26373268.

- Porter-Armstrong AP, Moore ZE, Bradbury I, McDonough S (May 2018). "Education of healthcare professionals for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (5): CD011620. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011620.pub2. PMC 6494581. PMID 29800486.

- O'Connor T, Moore ZE, Patton D (February 2021). "Patient and lay carer education for preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (3): CD012006. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012006.pub2. PMC 8095034. PMID 33625741.

- Moore ZE, Webster J (December 2018). "Dressings and topical agents for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12): CD009362. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009362.pub3. PMC 6517041. PMID 30537080.

- Zhang Q, Sun Z, Yue J (June 2015). "Massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD010518. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010518.pub2. PMID 26081072.

- Arora M, Harvey LA, Glinsky JV, Nier L, Lavrencic L, Kifley A, Cameron ID, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (January 2020). "Electrical stimulation for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD012196. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012196.pub2. PMC 6984413. PMID 31962369.

- "510(k)s Final Decisions Rendered for January 2004: Device: Medical Maggots". FDA. Archived from the original on 2009-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G (June 2017). "Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD011947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2. PMC 6481609. PMID 28639707.

- Sipponen A, Jokinen JJ, Sipponen P, Papp A, Sarna S, Lohi J (May 2008). "Beneficial effect of resin salve in treatment of severe pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized and controlled multicentre trial". The British Journal of Dermatology. 158 (5): 1055–1062. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08461.x. PMID 18284391. S2CID 12350060.

- Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G (June 2017). "Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2. PMC 6481609. PMID 28639707.

- Dumville JC, Keogh SJ, Liu Z, Stubbs N, Walker RM, Fortnam M (May 2015). "Alginate dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD011277. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011277.pub2. hdl:10072/81471. PMID 25994366.

- Walker RM, Gillespie BM, Thalib L, Higgins NS, Whitty JA (October 2017). "Foam dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10): CD011332. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011332.pub2. PMC 6485618. PMID 29025198.

- Dumville JC, Stubbs N, Keogh SJ, Walker RM, Liu Z (February 2015). Dumville JC (ed.). "Hydrogel dressings for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (2): CD011226. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011226. hdl:10072/81469. PMID 25914909.

- DeMarco S. "Wound and Pressure Ulcer Management". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- Naing C, Whittaker MA (June 2017). "Anabolic steroids for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD011375. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011375.pub2. PMC 6481474. PMID 28631809.

- Dumville JC, Webster J, Evans D, Land L (May 2015). "Negative pressure wound therapy for treating pressure ulcers" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD011334. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011334.pub2. PMID 25992684.

- Chen C, Hou WH, Chan ES, Yeh ML, Lo HL (July 2014). "Phototherapy for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD009224. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009224.pub2. PMID 25019295.

- McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Leung V (October 2018). "Support surfaces for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD009490. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009490.pub2. PMC 6517160. PMID 30307602.

- Wong JK, Amin K, Dumville JC (December 2016). "Reconstructive surgery for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (12): CD012032. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012032.pub2. PMC 6463961. PMID 27919120.

- Baba-Akbari Sari A, Flemming K, Cullum NA, Wollina U (July 2006). "Therapeutic ultrasound for pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001275. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001275.pub2. PMID 16855964.

- Hao XY, Li HL, Su H, Cai H, Guo TK, Liu R, et al. (February 2017). "Topical phenytoin for treating pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (2): CD008251. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008251.pub2. PMC 6464402. PMID 28225152.

- McGinnis E, Stubbs N (February 2014). "Pressure-relieving devices for treating heel pressure ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005485. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005485.pub3. PMID 24519736.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals". Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 14 (4): 208–15. 2001. doi:10.1097/00129334-200107000-00015. PMID 11902346.

- Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, Gunningberg L, Defloor T (April 2007). "Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 13 (2): 227–35. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00684.x. PMID 17378869.

- Anthony D, Papanikolaou P, Parboteeah S, Saleh M (November 2010). "Do risk assessment scales for pressure ulcers work?". Journal of Tissue Viability. 19 (4): 132–36. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2009.11.006. PMID 20036124.

- Li Y, Yin J, Cai X, Temkin-Greener J, Mukamel DB (July 2011). "Association of race and sites of care with pressure ulcers in high-risk nursing home residents". JAMA. 306 (2): 179–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.942. PMC 4108174. PMID 21750295.

Nathaniel Avilla, John Soto, Toni Tweedy, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews diariodelyaqui

Further reading

- Lyder CH, Ayello EA (April 2008). "Pressure Ulcers: A Patient Safety Issue". In Hughes RG (ed.). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Advances in Patient Safety. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). PMID 21328751.

- Qaseem A, Mir TP, Starkey M, Denberg TD (March 2015). "Risk assessment and prevention of pressure ulcers: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (5): 359–69. doi:10.7326/M14-1567. PMID 25732278.

- Sukino Health Care Solutions (21 October 2019). "How to prevent and deal with bedsores before it is too late". sukino.com.

External links

Media related to Pressure ulcers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pressure ulcers at Wikimedia Commons