History of dental treatments

The history of dental treatments dates back to thousands of years.[1][2] The scope of this article is limited to the pre-1981 history.

The earliest known example of dental caries manipulation is found in a Paleolithic man, dated between 14,160 and 13,820 BP.[3] The earliest known use of a filling after removal of decayed or infected pulp is found in a Paleolithic who lived near modern-day Tuscany, Italy, from 13,000 to 12,740 BP.[4] Although inconclusive, researchers have suggested that rudimentary dental procedures have been performed as far back as 130,000 years ago by Neanderthals.[5] Regarding implants, one of the milestone progress is osseointegration which was termed in 1981 by Tomas Albrektsson.[6]

Dental implants

There is archeological evidence that humans have attempted to replace missing teeth with root form implants for thousands of years. Remains from ancient China (dating 4000 years ago) have carved bamboo pegs, tapped into the bone, to replace lost teeth, and 2000-year-old remains from ancient Egypt have similarly shaped pegs made of precious metals. Some Egyptian mummies were found to have transplanted human teeth, and in other instances, teeth made of ivory.[1]: 26 [2][7] Wilson Popenoe and his wife in 1931, at a site in Honduras dating back to 600 AD, found the lower mandible of a young Mayan woman, with three missing incisors replaced by pieces of sea shells, shaped to resemble teeth.[8] Bone growth around two of the implants, and the formation of calculus, indicates that they were functional as well as esthetic. The fragment is currently part of the Osteological Collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.[1][2]

In modern times, a tooth replica implant was reported as early as 1969, but the polymethacrylate tooth analogue was encapsulated by soft tissue rather than osseointegrated.[9]

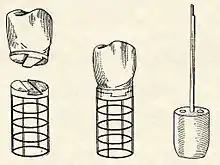

The early part of the 20th century saw a number of implants made of a variety of materials. One of the earliest successful implants was the Greenfield implant system of 1913 (also known as the Greenfield crib or basket).[10] Greenfield's implant, an iridioplatinum implant attached to a gold crown, showed evidence of osseointegration and lasted for a number of years.[10] The first use of titanium as an implantable material was by Bothe, Beaton and Davenport in 1940, who observed how close the bone grew to titanium screws, and the difficulty they had in extracting them.[11] Bothe et al. were the first researchers to describe what would later be called osseointegration (a name that would be marketed later on by Per-Ingvar Brånemark). In 1951, Gottlieb Leventhal implanted titanium rods in rabbits.[12] Leventhal's positive results led him to believe that titanium represented the ideal metal for surgery.[12]

In the 1950s research was being conducted at Cambridge University in England on blood flow in living organisms. These workers devised a method of constructing a chamber of titanium which was then embedded into the soft tissue of the ears of rabbits. In 1952 the Swedish orthopaedic surgeon, Per-Ingvar Brånemark, was interested in studying bone healing and regeneration. During his research time at Lund University he adopted the Cambridge designed "rabbit ear chamber" for use in the rabbit femur. Following the study, he attempted to retrieve these expensive chambers from the rabbits and found that he was unable to remove them. Brånemark observed that bone had grown into such close proximity with the titanium that it effectively adhered to the metal. Brånemark carried out further studies into this phenomenon, using both animal and human subjects, which all confirmed this unique property of titanium. Leonard Linkow, in the 1950s, was one of the first to insert titanium and other metal implants into the bones of the jaw. Artificial teeth were then attached to these pieces of metal.[13] In 1965 Brånemark placed his first titanium dental implant into a human volunteer. He began working in the mouth as it was more accessible for continued observations and there was a high rate of missing teeth in the general population offered more subjects for widespread study. He termed the clinically observed adherence of bone with titanium as "osseointegration".[14]: 626 Since then implants have evolved into three basic types:

- Root form implants; the most common type of implant indicated for all uses. Within the root form type of implant, there are roughly 18 variants, all made of titanium but with different shapes and surface textures. There is limited evidence showing that implants with relatively smooth surfaces are less prone to peri-implantitis than implants with rougher surfaces and no evidence showing that any particular type of dental implant has superior long-term success.[15]

- Zygoma Implant; a long implant that can anchor to the cheek bone by passing through the maxillary sinus to retain a complete upper denture when bone is absent. While zygomatic implants offer a novel approach to severe bone loss in the upper jaw, it has not been shown to offer any advantage over bone grafting functionally although it may offer a less invasive option, depending on the size of the reconstruction required.[16]

- Small diameter implants are implants of low diameter with one piece construction (implant and abutment) that are sometimes used for denture retention or orthodontic anchorage.[17]

Ceramic implants made from alumina were introduced between 1960s and 1970s but were eventually withdrawn from the market in the early 1990s because they presented some biomechanical problems (like low fracture toughness) and were replaced by zirconia implants.[18]

Robot-assisted dental surgery, including for dental implants,[19] has also been developed in the 2000s.[20]

Dentures

As early as the 7th century BC, Etruscans in northern Italy made partial dentures out of human or other animal teeth fastened together with gold bands.[22] The Romans had likely borrowed this technique by the 5th century BC.[22]

Wooden full dentures were invented in Japan around the early 16th century.[21] Softened bees wax was inserted into the patient's mouth to create an impression, which was then filled with harder bees wax. Wooden dentures were then meticulously carved based on that model. The earliest of these dentures were entirely wooden, but later versions used natural human teeth or sculpted pagodite, ivory, or animal horn for the teeth. These dentures were built with a broad base, exploiting the principles of adhesion to stay in place. This was an advanced technique for the era; it would not be replicated in the West until the late 18th century. Wooden dentures continued to be used in Japan until the Opening of Japan to the West in the 19th century.[21]

In 1728, Pierre Fauchard described the construction of dentures using a metal frame and teeth sculpted from animal bone.[21] The first porcelain dentures were made around 1770 by Alexis Duchâteau. In 1791, the first British patent was granted to Nicholas Dubois De Chemant, previous assistant to Duchateau, for 'De Chemant's Specification':

[...] a composition for the purpose of making of artificial teeth either single double or in rows or in complete sets, and also springs for fastening or affixing the same in a more easy and effectual manner than any hitherto discovered which said teeth may be made of any shade or colour, which they will retain for any length of time and will consequently more perfectly resemble the natural teeth.[23]

He began selling his wares in 1792, with most of his porcelain paste supplied by Wedgwood.[24][25]

17th century London's Peter de la Roche is believed to be one of the first 'operators for the teeth', men who advertised themselves as specialists in dental work. They were often professional goldsmiths, ivory turners or students of barber-surgeons.[26]

In 1820, Samuel Stockton, a goldsmith by trade, began manufacturing high-quality porcelain dentures mounted on 18-carat gold plates. Later dentures from the 1850s on were made of Vulcanite, a form of hardened rubber into which porcelain teeth were set. In the 20th century, acrylic resin and other plastics were used.[27] In Britain, sequential Adult Dental Health Surveys revealed that in 1968 79% of those aged 65–74 had no natural teeth; by 1998, this proportion had fallen to 36%.[28]

George Washington (1732–1799) had problems with his teeth throughout his life, and historians have tracked his experiences in great detail.[29] He lost his first adult tooth when he was twenty-two and had only one left by the time he became president.[30] John Adams says he lost them because he used them to crack Brazil nuts but modern historians suggest the mercury oxide, which he was given to treat illnesses such as smallpox and malaria, probably contributed to the loss. He had several sets of false teeth made, four of them by a dentist named John Greenwood. None of the sets, contrary to popular belief, were made from wood or contained any wood.[31] The set made when he became president were carved from hippopotamus and elephant ivory, held together with gold springs.[32] Prior to these, he had a set made with real human teeth,[33] likely ones he purchased from "several unnamed Negroes, presumably Mount Vernon slaves" in 1784.[34] Washington's dental problems left him in constant pain, for which he took laudanum.[35] This distress may be apparent in many of the portraits painted while he was still in office,[35] including the one still used on the $1 bill.[36][lower-alpha 1]

Notes

- The Smithsonian Institution states in "The Portrait—George Washington: A National Treasure" that:

- Stuart admired the sculpture of Washington by French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon, probably because it was based on a life mask and therefore extremely accurate. Stuart explained, "When I painted him, he had just had a set of false teeth inserted, which accounts for the constrained expression so noticeable about the mouth and lower part of the face. Houdon's bust does not suffer from this defect. I wanted him as he looked at that time." Stuart preferred the Athenaeum pose and, except for the gaze, used the same pose for the Lansdowne painting.[35]

References

- Misch, Carl E (2007). Contemporary Implant Dentistry. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier.

- Balaji, S. M. (2007). Textbook of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. New Delhi: Elsevier India. pp. 301–302. ISBN 9788131203002.

- Oxilia, Gregorio; Peresani, Marco; Romandini, Matteo; Matteucci, Chiara; Spiteri, Cynthianne Debono; Henry, Amanda G.; Schulz, Dieter; Archer, Will; Crezzini, Jacopo; Boschin, Francesco; Boscato, Paolo (2015-07-16). "Earliest evidence of dental caries manipulation in the Late Upper Palaeolithic". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 12150. Bibcode:2015NatSR...512150O. doi:10.1038/srep12150. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4504065. PMID 26179739.

- Oxilia, Gregorio; Fiorillo, Flavia; Boschin, Francesco; Boaretto, Elisabetta; Apicella, Salvatore A.; Matteucci, Chiara; Panetta, Daniele; Pistocchi, Rossella; Guerrini, Franca; Margherita, Cristiana; Andretta, Massimo (July 2017). "The dawn of dentistry in the late upper Paleolithic: An early case of pathological intervention at Riparo Fredian". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 163 (3): 446–461. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23216. hdl:11585/600517. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 28345756.

- "KU Discoveries of Neanderthal teeth marks uncovers evidence of prehistoric dentistry". The University of Kansas. 2017-06-23. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- Albrektsson, T; Branemark, PI; Hansson, HA; Lindstrom, J (1981). "Osseointegrated titanium implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to- implant anchorage in man". Acta Orthop Scand. 52 (2): 155–170. doi:10.3109/17453678108991776. PMID 7246093.

- Anusavice, Kenneth J. (2003). Phillips' Science of Dental Materials. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7020-2903-5.

- Misch, Carl E (2015). "Chapter 2: Generic Root Form Component Terminology". Dental Implant Prosthetics (2nd ed.). Mosby. pp. 26–45. ISBN 9780323078450.

- Hodosh, M; Shklar, G; Povar, M (1974). "The porous vitreous carbon/polymethacrylate tooth implant: Preliminary studies". J. Prosthet. Dent. 32 (3): 326–334. doi:10.1016/0022-3913(74)90037-7. PMID 4612143.

- Greenfield, E.J. (1913). "Implantation of artificial crown and bridge abutments". Dental Cosmos. 55: 364–369.

- Bothe, R.T.; Beaton, K.E.; Davenport, H.A. (1940). "Reaction of bone to multiple metallic implants". Surg Gynecol Obstet. 71: 598–602.

- Leventhal, Gottlieb S. (1951). "Titanium, a metal for surgery". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 33-A (2): 473–474. doi:10.2106/00004623-195133020-00021. PMID 14824196.

- Fraunhofer, J.A. von (2013). Dental materials at a glance (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 115. ISBN 9781118646649.

- Newman, Michael; Takei, Henry; Klokkevold, Perry, eds. (2012). Carranza's Clinical Periodontology (in English). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 9781437704167.

- Esposito, Marco; Ardebili, Yasmin; Worthington, Helen V. (2014-07-22). "Interventions for replacing missing teeth: different types of dental implants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD003815. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003815.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25048469.

- Esposito, M.; Worthington, H. V. (2013). "Interventions for replacing missing teeth: dental implants in zygomatic bone for the rehabilitation of the severely deficient edentulous maxilla". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews): CD004151. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004151.pub3. PMC 7197366. PMID 24009079.

- Chen, Y.; Kyung, H. M.; Zhao, W. T.; Yu, W. J. (2009). "Critical factors for the success of orthodontic mini-implants: A systematic review". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 135 (3): 284–291. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.08.017. PMID 19268825.

- Cionca, Norbert; Hashim, Dena; Mombelli, Andrea (2017). "Zirconia dental implants: where are we now, and where are we heading?". Periodontology 2000. 73 (1): 241–258. doi:10.1111/prd.12180. ISSN 1600-0757. PMID 28000266.

- "Implant Surgical Guides: State of the Art". HammasOskari. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Lorsakul A, Suthakorn J. Vol. 21. International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics; 2009. Toward robot-assisted dental surgery: Path generation and navigation system using optical tracking. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE; pp. 1212–6.

- Moriyama, N. & Hasegawa, M. (1987). "The history of the characteristic Japanese wooden denture". Bulletin of the History of Dentistry. 35 (1): 9–16. PMID 3552092.

- Donaldson, J. A. (1980). "The use of gold in dentistry" (PDF). Gold Bulletin. 13 (3): 117–124. doi:10.1007/BF03216551. PMID 11614516. S2CID 137571298.

- British Journal of Dental Science, Volume 4. Vol. IV (62):p.208. London: John Churchill. August 1861. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- "Dental art: A French dentist showing his artificial teeth". British Dental Association. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011.

- "The Henry J. McKellops Collection in Dental Medicine".

- John Woodforde, The Strange Story of False Teeth, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968

- Eden S. E.; Kerr W. J. S.; Brown J. (2002). "A clinical trial of light cure acrylic resin for orthodontic use". Journal of Orthodontics. 29 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1093/ortho/29.1.51. PMID 11907310.

- Murray JJ (Nov 2011). "Adult dental health surveys: 40 years on". Br Dent J. 211 (9): 407–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.903. PMID 22075880.

- Van Horn, Jennifer (2016). "George Washington's Dentures: Disability, Deception, and the Republican Body". Early American Studies. 14: 2–47. doi:10.1353/eam.2016.0000. S2CID 147542950.

- Lloyd, John; Mitchinson, John (2006). The Book of General Ignorance. New York: Harmony Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-307-39491-0. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- Earls, Stephanie (22 February 2014). "Re-enactor brings George Washington to life". The Washington Times. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Glover, Barbara (Summer–Fall 1998). "George Washington—A Dental Victim". The Riversdale Letter. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- Dentures, 1790–1799 Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate, Museum and Gardens

- Mary V. Thompson, "The Private Life of George Washington's Slaves", Frontline, PBS

- "The Portrait—George Washington:A National Treasure". Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- Stuart, Gilbert. "George Washington (the Athenaeum portrait)". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.