Endocrinology

Endocrinology (from endocrine + -ology) is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the integration of developmental events proliferation, growth, and differentiation, and the psychological or behavioral activities of metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sleep, digestion, respiration, excretion, mood, stress, lactation, movement, reproduction, and sensory perception caused by hormones. Specializations include behavioral endocrinology[1][2][3] and comparative endocrinology.

Illustration depicting the primary endocrine organs of a female | |

| System | Endocrine |

|---|---|

| Significant diseases | Diabetes, Thyroid disease, Androgen excess |

| Significant tests | Thyroid function tests, Blood sugar levels |

| Specialist | Endocrinologist |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

The endocrine system consists of several glands, all in different parts of the body, that secrete hormones directly into the blood rather than into a duct system. Therefore, endocrine glands are regarded as ductless glands. Hormones have many different functions and modes of action; one hormone may have several effects on different target organs, and, conversely, one target organ may be affected by more than one hormone.

The endocrine system

Endocrinology is the study of the endocrine system in the human body.[4] This is a system of glands which secrete hormones. Hormones are chemicals that affect the actions of different organ systems in the body. Examples include thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and insulin. The endocrine system involves a number of feedback mechanisms, so that often one hormone (such as thyroid stimulating hormone) will control the action or release of another secondary hormone (such as thyroid hormone). If there is too much of the secondary hormone, it may provide negative feedback to the primary hormone, maintaining homeostasis.

In the original 1902 definition by Bayliss and Starling (see below), they specified that, to be classified as a hormone, a chemical must be produced by an organ, be released (in small amounts) into the blood, and be transported by the blood to a distant organ to exert its specific function. This definition holds for most "classical" hormones, but there are also paracrine mechanisms (chemical communication between cells within a tissue or organ), autocrine signals (a chemical that acts on the same cell), and intracrine signals (a chemical that acts within the same cell).[5] A neuroendocrine signal is a "classical" hormone that is released into the blood by a neurosecretory neuron (see article on neuroendocrinology).

Hormones

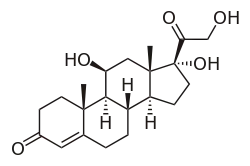

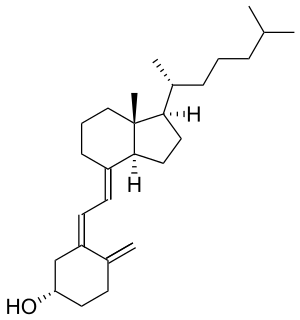

Griffin and Ojeda identify three different classes of hormones based on their chemical composition:[6]

Amines

Amines, such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine (catecholamines), are derived from single amino acids, in this case tyrosine. Thyroid hormones such as 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) and 3,5,3’,5’-tetraiodothyronine (thyroxine, T4) make up a subset of this class because they derive from the combination of two iodinated tyrosine amino acid residues.

Peptide and protein

Peptide hormones and protein hormones consist of three (in the case of thyrotropin-releasing hormone) to more than 200 (in the case of follicle-stimulating hormone) amino acid residues and can have a molecular mass as large as 31,000 grams per mole. All hormones secreted by the pituitary gland are peptide hormones, as are leptin from adipocytes, ghrelin from the stomach, and insulin from the pancreas.

Steroid

Steroid hormones are converted from their parent compound, cholesterol. Mammalian steroid hormones can be grouped into five groups by the receptors to which they bind: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, androgens, estrogens, and progestogens. Some forms of vitamin D, such as calcitriol, are steroid-like and bind to homologous receptors, but lack the characteristic fused ring structure of true steroids.

As a profession

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Doctor, Medical specialist |

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Although every organ system secretes and responds to hormones (including the brain, lungs, heart, intestine, skin, and the kidneys), the clinical specialty of endocrinology focuses primarily on the endocrine organs, meaning the organs whose primary function is hormone secretion. These organs include the pituitary, thyroid, adrenals, ovaries, testes, and pancreas.

An endocrinologist is a physician who specializes in treating disorders of the endocrine system, such as diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and many others (see list of diseases).

Work

The medical specialty of endocrinology involves the diagnostic evaluation of a wide variety of symptoms and variations and the long-term management of disorders of deficiency or excess of one or more hormones.

The diagnosis and treatment of endocrine diseases are guided by laboratory tests to a greater extent than for most specialties. Many diseases are investigated through excitation/stimulation or inhibition/suppression testing. This might involve injection with a stimulating agent to test the function of an endocrine organ. Blood is then sampled to assess the changes of the relevant hormones or metabolites. An endocrinologist needs extensive knowledge of clinical chemistry and biochemistry to understand the uses and limitations of the investigations.

A second important aspect of the practice of endocrinology is distinguishing human variation from disease. Atypical patterns of physical development and abnormal test results must be assessed as indicative of disease or not. Diagnostic imaging of endocrine organs may reveal incidental findings called incidentalomas, which may or may not represent disease.

Endocrinology involves caring for the person as well as the disease. Most endocrine disorders are chronic diseases that need lifelong care. Some of the most common endocrine diseases include diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and the metabolic syndrome. Care of diabetes, obesity and other chronic diseases necessitates understanding the patient at the personal and social level as well as the molecular, and the physician–patient relationship can be an important therapeutic process.

Apart from treating patients, many endocrinologists are involved in clinical science and medical research, teaching, and hospital management.

Training

Endocrinologists are specialists of internal medicine or pediatrics. Reproductive endocrinologists deal primarily with problems of fertility and menstrual function—often training first in obstetrics. Most qualify as an internist, pediatrician, or gynecologist for a few years before specializing, depending on the local training system. In the U.S. and Canada, training for board certification in internal medicine, pediatrics, or gynecology after medical school is called residency. Further formal training to subspecialize in adult, pediatric, or reproductive endocrinology is called a fellowship. Typical training for a North American endocrinologist involves 4 years of college, 4 years of medical school, 3 years of residency, and 2 years of fellowship. In the US, adult endocrinologists are board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) or the American Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine (AOBIM) in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism.

Diseases and medicine

Diseases

- See main article at Endocrine diseases

Endocrinology also involves the study of the diseases of the endocrine system. These diseases may relate to too little or too much secretion of a hormone, too little or too much action of a hormone, or problems with receiving the hormone.

Societies and organisations

Because endocrinology encompasses so many conditions and diseases, there are many organizations that provide education to patients and the public. The Hormone Foundation is the public education affiliate of The Endocrine Society and provides information on all endocrine-related conditions. Other educational organizations that focus on one or more endocrine-related conditions include the American Diabetes Association, Human Growth Foundation, American Menopause Foundation, Inc., and Thyroid Foundation of America.

In North America the principal professional organizations of endocrinologists include The Endocrine Society,[7] the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists,[8] the American Diabetes Association,[9] the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society,[10] and the American Thyroid Association.[11]

In Europe, the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) are the main organisations representing professionals in the fields of adult and paediatric endocrinology, respectively.

In the United Kingdom, the Society for Endocrinology[12] and the British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes[13] are the main professional organisations.

The European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology[14] is the largest international professional association dedicated solely to paediatric endocrinology. There are numerous similar associations around the world.

History

The earliest study of endocrinology began in China.[15] The Chinese were isolating sex and pituitary hormones from human urine and using them for medicinal purposes by 200 BC.[15] They used many complex methods, such as sublimation of steroid hormones.[15] Another method specified by Chinese texts—the earliest dating to 1110—specified the use of saponin (from the beans of Gleditsia sinensis) to extract hormones, but gypsum (containing calcium sulfate) was also known to have been used.[15]

Although most of the relevant tissues and endocrine glands had been identified by early anatomists, a more humoral approach to understanding biological function and disease was favoured by the ancient Greek and Roman thinkers such as Aristotle, Hippocrates, Lucretius, Celsus, and Galen, according to Freeman et al.,[16] and these theories held sway until the advent of germ theory, physiology, and organ basis of pathology in the 19th century.

In 1849, Arnold Berthold noted that castrated cockerels did not develop combs and wattles or exhibit overtly male behaviour.[17] He found that replacement of testes back into the abdominal cavity of the same bird or another castrated bird resulted in normal behavioural and morphological development, and he concluded (erroneously) that the testes secreted a substance that "conditioned" the blood that, in turn, acted on the body of the cockerel. In fact, one of two other things could have been true: that the testes modified or activated a constituent of the blood or that the testes removed an inhibitory factor from the blood. It was not proven that the testes released a substance that engenders male characteristics until it was shown that the extract of testes could replace their function in castrated animals. Pure, crystalline testosterone was isolated in 1935.[18]

Graves' disease was named after Irish doctor Robert James Graves,[19] who described a case of goiter with exophthalmos in 1835. The German Karl Adolph von Basedow also independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840, while earlier reports of the disease were also published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajani and Antonio Giuseppe Testa, in 1802 and 1810 respectively,[20] and by the English physician Caleb Hillier Parry (a friend of Edward Jenner) in the late 18th century.[21] Thomas Addison was first to describe Addison's disease in 1849.[22]

In 1902 William Bayliss and Ernest Starling performed an experiment in which they observed that acid instilled into the duodenum caused the pancreas to begin secretion, even after they had removed all nervous connections between the two.[23] The same response could be produced by injecting extract of jejunum mucosa into the jugular vein, showing that some factor in the mucosa was responsible. They named this substance "secretin" and coined the term hormone for chemicals that act in this way.

Joseph von Mering and Oskar Minkowski made the observation in 1889 that removing the pancreas surgically led to an increase in blood sugar, followed by a coma and eventual death—symptoms of diabetes mellitus. In 1922, Banting and Best realized that homogenizing the pancreas and injecting the derived extract reversed this condition.[24]

Neurohormones were first identified by Otto Loewi in 1921.[25] He incubated a frog's heart (innervated with its vagus nerve attached) in a saline bath, and left in the solution for some time. The solution was then used to bathe a non-innervated second heart. If the vagus nerve on the first heart was stimulated, negative inotropic (beat amplitude) and chronotropic (beat rate) activity were seen in both hearts. This did not occur in either heart if the vagus nerve was not stimulated. The vagus nerve was adding something to the saline solution. The effect could be blocked using atropine, a known inhibitor to heart vagal nerve stimulation. Clearly, something was being secreted by the vagus nerve and affecting the heart. The "vagusstuff" (as Loewi called it) causing the myotropic (muscle enhancing) effects was later identified to be acetylcholine and norepinephrine. Loewi won the Nobel Prize for his discovery.

Recent work in endocrinology focuses on the molecular mechanisms responsible for triggering the effects of hormones. The first example of such work being done was in 1962 by Earl Sutherland. Sutherland investigated whether hormones enter cells to evoke action, or stayed outside of cells. He studied norepinephrine, which acts on the liver to convert glycogen into glucose via the activation of the phosphorylase enzyme. He homogenized the liver into a membrane fraction and soluble fraction (phosphorylase is soluble), added norepinephrine to the membrane fraction, extracted its soluble products, and added them to the first soluble fraction. Phosphorylase activated, indicating that norepinephrine's target receptor was on the cell membrane, not located intracellularly. He later identified the compound as cyclic AMP (cAMP) and with his discovery created the concept of second-messenger-mediated pathways. He, like Loewi, won the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work in endocrinology.[26]

See also

References

- Nelson, R. J. 2005. An Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology, Fourth Edition. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- "Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology". idea.ucr.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Behavioral Endocrinology". www-rci.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Specialty Description". American Medical Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Nussey S; Whitehead S (2001). Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publ. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7.

- Ojeda, Sergio R.; Griffin, James Bennett (2000). Textbook of endocrine physiology (4th ed.). Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513541-1.

- "Home - Endocrine Society". www.endo-society.org.

- "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists".

- "American Diabetes Association". American Diabetes Association.

- "Pediatric Endocrine Society". www.lwpes.org.

- "American Thyroid Association - ATA". www.thyroid.org.

- "Society for Endocrinology - A world-leading authority on hormones". www.endocrinology.org.

- "BSPED - Home". www.bsped.org.uk.

- "ESPE - European Society of Paediatric Endocrinology - Improving the clinical care of children and adolescents with endocrine conditions". www.eurospe.org.

- Temple, Robert (2007) [1986]. The genius of China: 3,000 years of science, discovery & invention (3rd ed.). London: Andre Deutsch. pp. 141–145. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6.

- Freeman ER; Bloom DA; McGuire EJ (2001). "A brief history of testosterone". Journal of Urology. 165 (2): 371–3. doi:10.1097/00005392-200102000-00004. PMID 11176375.

- Berthold AA (1849). "Transplantation der Hoden". Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wiss. Med. 16: 42–6.

- David K; Dingemanse E; Freud J; et al. (1935). "Uber krystallinisches mannliches Hormon aus Hoden (Testosteron) wirksamer als aus harn oder aus Cholesterin bereitetes Androsteron". Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 233 (5–6): 281–283. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1935.233.5-6.281.

- Robert James Graves at Who Named It?

- Giuseppe Flajani at Who Named It?

- Hull G (1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755–1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. doi:10.1177/014107689809100618. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- Ten S; New M; Maclaren N (2001). "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 86 (7): 2909–22. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.7.7636. PMID 11443143.

- Bayliss, W. M.; Starling, E. H. (1902-09-12). "The mechanism of pancreatic secretion". The Journal of Physiology. Wiley. 28 (5): 325–353. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1902.sp000920. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 1540572. PMID 16992627.

- Bliss M (1989). "J. J. R. Macleod and the discovery of insulin". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 74 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1989.sp003266. PMID 2657840.

- Loewi, O. Uebertragbarkeit der Herznervenwirkung. Pfluger's Arch. ges Physiol. 1921;189:239-42.

- Sutherland EW (1972). "Studies on the mechanism of hormone action". Science. 177 (4047): 401–8. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..401S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4047.401. PMID 4339614.

-Triiodthyronine_Structural_Formulae_V2.svg.png.webp)