Oxyphil cell (parathyroid)

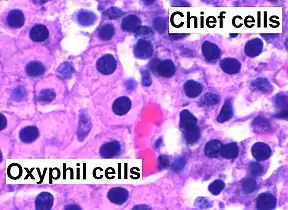

Parathyroid oxyphil cells are one out of the two types of cells found in the parathyroid gland, the other being parathyroid chief cell. [1] Oxyphil cells are only found in a select few number of species and humans are one of them.[2]

| Oxyphil cell | |

|---|---|

High magnification micrograph of parathyroid gland, stained using H&E stain. The cells with orange/pink staining cytoplasm are oxyphil cells | |

| Details | |

| Location | Parathyroid gland |

| Identifiers | |

| TH | H3.08.02.5.00005 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

These cells can be found in clusters in the center of the section and at the periphery.[3][4][5][6] Oxyphil cells appear at the onset of puberty, but have no known function. It is perceived that oxyphil cells may be derived from chief cells at puberty, as they are not present at birth like chief cells.[7] Oxyphil cells increase in number with age.[8]

Structure

The oxyphil cell are much larger in size (12–20 μm) compared with chief cells (6–8 μm) and also stain lighter than chief cells.[9] Oxyphil cells have a cytoplasm filled with many, large mitochondria. Oxyphil cells have abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and ribosomes that are interspersed between the mitochondria. The endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatuses, and secretory granules are poorly developed in oxyphil cells of normal parathyroid glands[2]

Function

With nuclear medicine scans, they selectively take up the Technetium-sestamibi complex radiotracer to allow delineation of glandular anatomy.[10] Oxyphil cells have been shown to express parathyroid-relevant genes found in the chief cells and have the potential to produce additional autocrine/paracrine factors, such as parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and calcitriol.[11] Oxyphil cells have also been shown to have higher oxidative and hydrolytic enzyme activity than chief cells due to having more mitochondria.[2] Oxyphil cells have significantly more calcium-sensing receptors (CaSRs) than chief cells.[12] More work needs to be done to fully understand the functions of these cells and their secretions.

References

- Histology image:15002loa from Vaughan, Deborah (2002). A Learning System in Histology: CD-ROM and Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195151732.

- Haschek, Wanda (2009). "Fundamentals of Toxicologic Pathology | ScienceDirect". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- Gartner, p. 208, Fig. 3

- Ross, p. 628, Fig. 1

- DiFiore, pp. 270 - 271

- Wheater, pp. 312 - 313

- Bilezikian, John (2015). The Parathyroids: Basic and Clinical Concepts. pp. 23–29. ISBN 978-0-12-397166-1.

- Birren, James (2007). Encyclopedia of Gerontology (Second ed.). California. pp. 480–494.

- Cinthia, Ritter. "Differential Gene Expression by Oxyphil and Chief Cells of Human Parathyroid Glands". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 97 (8): 1499–1508.

- "Minimally Invasive Radio-guided Surgery for Primary Hyperparathyroidism," Annals of Surgical Oncology 12/07 14(12) pp 3401-3402

- Ritter, Haughey, Miller, Brown (2012). "Differential gene expression by oxyphil and chief cells of human parathyroid glands". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 97 (8): E1499–505. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3366. PMC 3591682. PMID 22585091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rottembourg, Jacques (2019). "Are oxyphil cells responsible for the ineffectiveness of cinacalcet hydrochloride in haemodialysis patients?". Clinical Kidney Journal. 12 (3): 433–436. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfy062. PMC 6543953. PMID 31198545.