Inferior vena cava syndrome

Inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is a very rare constellation of symptoms resulting from either an obstruction, or stenosis of the inferior vena cava. It can be caused by physical invasion or compression by a pathological process or by thrombosis within the vein itself. It can also occur during pregnancy. Pregnancy leads to high venous pressure in the lower limbs, decreased blood return to the heart, decreased cardiac output due to obstruction of the inferior vena cava, sudden rise in venous pressure which can lead to placental separation, and a decrease in kidney function. All of these issues can arise from lying in the supine position during late pregnancy which can cause compression of the inferior vena cava by the uterus.[1] Symptoms of late pregnancy inferior vena cava syndrome consist of intense pain in the right hand side, muscle twitching, hypotension, and fluid retention.[2]

| Inferior vena cava syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

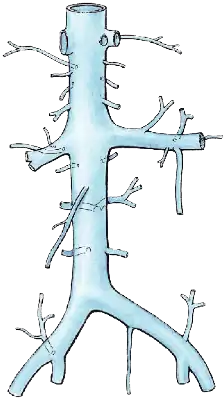

| Inferior vena cava | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Frequency | 5-10 out of 100,000 (From 1 in 10,000-20,000) |

Signs and symptoms

IVCS presents with a wide variety of signs and symptoms, making it difficult to diagnose clinically.

- Edema of the lower extremities (peripheral edema), caused by an increase in the venous blood pressure.

- Tachycardia. This is caused by the decreased preload, decreased cardiac output, and leads to increased frequency.

- In pregnant women, signs of fetal hypoxia and distress may be seen in the cardiotocography. This is caused by decreased perfusion of the uterus, resulting in hypoxemia of the fetus.

- Supine hypotensive syndrome

Causes

the causes for this condition are the following:

- Obstruction by deep vein thrombosis or tumors (most commonly renal cell carcinoma)

- Compression through external pressure by neighbouring structures or tumors, either by significantly compressing the vein or by promoting thrombosis by causing turbulence by disturbing the blood flow. This is quite common during the third trimester of pregnancy when the uterus compresses the vein in the right side position.

- Iatrogenic causes may be suspected in patients with a medical history of liver transplantion, vascular catheters, dialysis and other invasive procedures in the vicinity

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made clinically by observing the patient when in the right sided position where you can see multiple dilated veins over abdomen due to collaterals.[3] Ultrasound with Doppler flow measurement may be used to assess the IVC and circulatory system.

Treatment

Treatment will vary depending on the cause of the vena cava compression or interruption. Often, treatment includes positional changes, avoidance of supine positioning, especially on the right side. In pregnancy, definitive management of the IVCS is to deliver the baby. In other conditions, medical or surgical treatment to remove or relieve the offending structure will relieve symptoms.

Frequency

Epidemiological data is elusive owing to the wide variety of clinical presentation. In the U.S., incidence is estimated to be at 5–10 cases per 100,000 per year. Minor compression of the inferior vena cava during pregnancy is a relatively common occurrence. It is seen most commonly when women lie on their back or right side.[4] 90% of women lying in the supine position during pregnancy experience some form of inferior vena cava syndrome; however, not all of the women display symptoms.[4]

References

- D.B. Scott; M.G. Kerr (1963). "Inferior vena cave pressure in late pregnancy". BJOG. 70 (6): 1044–1049. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1963.tb15051.x. PMID 14100067.

- B. Howard; J. Goodson; W. Mengert (1953). "Supine hypotensive syndrome in late pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1 (4): 371–377. PMID 13055188.

- Parikh, Rohan; Beedkar, Amey (2018). "Inferior Vena Cava: Chronic Total Occlusion". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 93 (4): 548. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.03.001. PMID 29622107.

- M.G. Kerr; D.B. Scott; Eric Samuel (1964). "Studies of the inferior vena cava in late pregnancy". British Medical Journal. 1 (5382): 532–533. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5382.522. PMC 1813561. PMID 14101999.