Malaria vaccine

A malaria vaccine is a vaccine that is used to prevent malaria. The only approved use of a vaccine outside the EU, as of 2022, is RTS,S, known by the brand name Mosquirix.[1] In October 2021, the WHO for the first time recommended the large-scale use of a malaria vaccine for children living in areas with moderate-to-high malaria transmission. Four injections are required for full protection.[1]

Screened cup of malaria-infected mosquitoes which will infect a volunteer in a clinical trial | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | Malaria |

| Vaccine type | Protein subunit |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Mosquirix |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular[1] |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider |

|

Research continues with other malaria vaccines. The most effective malaria vaccine is R21/Matrix-M, with a 77% efficacy rate shown in initial trials and significantly higher antibody levels than with the RTS,S vaccine.[2] It is the first vaccine that meets the World Health Organization's (WHO) goal of a malaria vaccine with at least 75% efficacy.[3][2]

Approved vaccines

RTS,S

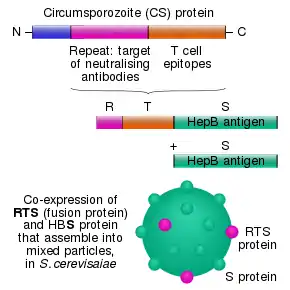

RTS,S, developed by PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative (MVI) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is the most recently developed recombinant vaccine. It consists of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) from the pre-erythrocytic stage. The CSP antigen causes the production of antibodies capable of preventing the invasion of hepatocytes and additionally elicits a cellular response enabling the destruction of infected hepatocytes. The CSP vaccine presented problems in the trial stage due to its poor immunogenicity. RTS,S attempted to avoid these by fusing the protein with a surface antigen from hepatitis B, creating a more potent and immunogenic vaccine. When tested in trials an emulsion of oil in water and the added adjuvants of monophosphoryl A and QS21 (SBAS2), the vaccine gave protective immunity to 7 out of 8 volunteers when challenged with P. falciparum.[4]

RTS,S/AS01 (commercial name Mosquirix),[5] was engineered using genes from the outer protein of P. falciparum malaria parasite and a portion of a hepatitis B virus plus a chemical adjuvant to boost the immune response. Infection is prevented by inducing high antibody titers that block the parasite from infecting the liver.[6] In November 2012, a Phase III trial of RTS,S found that it provided modest protection against both clinical and severe malaria in young infants.[7]

As of October 2013, preliminary results of a Phase III clinical trial indicated that RTS,S/AS01 reduced the number of cases among young children by almost 50 percent and among infants by around 25 percent. The study ended in 2014. The effects of a booster dose were positive, even though overall efficacy seems to wane with time. After four years, reductions were 36 percent for children who received three shots and a booster dose. Missing the booster dose reduced the efficacy against severe malaria to a negligible effect. The vaccine was shown to be less effective for infants. Three doses of vaccine plus a booster reduced the risk of clinical episodes by 26 percent over three years but offered no significant protection against severe malaria.[8]

In a bid to accommodate a larger group and guarantee a sustained availability for the general public, GSK applied for a marketing license with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in July 2014.[9] GSK treated the project as a non-profit initiative, with most funding coming from the Gates Foundation, a major contributor to malaria eradication.[10]

On 24 July 2015, Mosquirix received a positive scientific opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on the proposal for the vaccine to be used to vaccinate children aged 6 weeks to 17 months outside the European Union.[11][1] A pilot project for vaccination was launched on 23 April 2019, in Malawi, on 30 April 2019, in Ghana, and on 13 September 2019, in Kenya.[12][13]

In October 2021, the vaccine was endorsed by the World Health Organization for "broad use" in children, making it the first malaria vaccine to receive this recommendation.[14][15][16]

Agents under development

A completely effective vaccine is not available for malaria, although several vaccines are under development.[17] Multiple vaccine candidates targeting the blood-stage of the parasite's life cycle have been insufficient on their own.[18] Several potential vaccines targeting the pre-erythrocytic stage are being developed, with RTS,S the only approved option so far.[19][7]

R21/Matrix-M

The most effective malaria vaccine is R21/Matrix-M, with 77% efficacy shown in initial trials. It is the first vaccine that meets the World Health Organization's goal of a malaria vaccine with at least 75% efficacy.[3] It was developed through a collaboration involving the University of Oxford, the Kenya Medical Research Institute, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Novavax, the Serum Institute of India, and the Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé in Nanoro, Burkina Faso. The R21 vaccine uses a circumsporozoite protein (CSP) antigen, at a higher proportion than the RTS,S vaccine. It includes the Matrix-M adjuvant that is also utilized in the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine.[20]

A Phase II trial was reported in April 2021, with a vaccine efficacy of 77% and antibody levels significantly higher than with the RTS,S vaccine. A booster shot of R21/Matrix-M that is given 12 months after the primary three-dose regimen maintains a high efficacy against malaria, providing high protection against symptomatic malaria for at least 2 years.[21] A Phase III trial is currently underway with 4,800 children across four African countries, with results expected later in 2022.[22]

Nanoparticle enhancement of RTS,S

In 2015, researchers used a repetitive antigen display technology to engineer a nanoparticle that displayed malaria specific B cell and T cell epitopes. The particle exhibited icosahedral symmetry and carried on its surface up to 60 copies of the RTS,S protein. The researchers claimed that the density of the protein was much higher than the 14% of the GSK vaccine.[23][24]

PfSPZ vaccine

The PfSPZ vaccine is a candidate malaria vaccine developed by Sanaria using radiation-attenuated sporozoites to elicit an immune response. Clinical trials have been promising, with trials in Africa, Europe, and the US protecting over 80% of volunteers.[25] It has been subject to some criticism regarding the ultimate feasibility of large-scale production and delivery in Africa, since it must be stored in liquid nitrogen.

The PfSPZ vaccine candidate was granted fast track designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in September 2016.[26]

In April 2019, a phase 3 trial in Bioko was announced, scheduled to start in early 2020.[27]

Other developments

- SPf66 is a synthetic peptide based vaccine developed by the Manuel Elkin Patarroyo team in Colombia, and was tested extensively in endemic areas in the 1990s. Clinical trials showed it to be insufficiently effective, with 28% efficacy in South America and minimal or no efficacy in Africa.[28] This vaccine had no protective effect in the largest placebo controlled randomized trial in South East Asia and was abandoned.[29]

- The CSP (Circum-Sporozoite Protein) was a vaccine developed that initially appeared promising enough to undergo trials. It is also based on the circumsporozoite protein, but additionally has the recombinant (Asn-Ala-Pro15Asn-Val-Asp-Pro)2-Leu-Arg(R32LR) protein covalently bound to a purified Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin (A9). However, at an early stage, a complete lack of protective immunity was demonstrated in those inoculated. The study group used in Kenya had an 82% incidence of parasitaemia while the control group only had an 89% incidence. The vaccine intended to cause an increased T-lymphocyte response in those exposed; this was also not observed.

- The NYVAC-Pf7 multi-stage vaccine attempted to use different technology, incorporating seven P. falciparum antigenic genes. These came from a variety of stages during the life cycle. CSP and sporozoite surface protein 2 (called PfSSP2) were derived from the sporozoite phase. The liver stage antigen 1 (LSA1), three from the erythrocytic stage (merozoite surface protein 1, serine repeat antigen, and AMA-1), and one sexual stage antigen (the 25-kDa Pfs25) were included. This was first investigated using rhesus monkeys and produced encouraging results: 4 out of the 7 antigens produced specific antibody responses (CSP, PfSSP2, MSP1 and PFs25). Later trials in humans, despite demonstrating cellular immune responses in over 90% of the subjects, had very poor antibody responses. Despite this following administration of the vaccine, some candidates had complete protection when challenged with P. falciparum. This result has warranted ongoing trials.

- In 1995 a field trial involving [NANP]19-5.1 proved to be very successful. Out of 194 children vaccinated, none developed symptomatic malaria in the 12-week follow-up period, and only 8 failed to have higher levels of antibody present. The vaccine consists of the schizont export protein (5.1) and 19 repeats of the sporozoite surface protein [NANP]. Limitations of the technology exist as it contains only 20% peptide and has low levels of immunogenicity. It also does not contain any immunodominant T-cell epitopes.[30]

- A chemical compound undergoing trials for the treatment of tuberculosis and cancer—the JmJc inhibitor ML324 and the antitubercular clinical candidate SQ109—is potentially a new line of drugs to treat malaria and kill the parasite in its infectious stage. More tests still need to be carried out before the compounds would be approved as a viable treatment.[31]

Considerations

The task of developing a preventive vaccine for malaria is a complex process. There are a number of considerations to be made concerning what strategy a potential vaccine should adopt.

Parasite diversity

P. falciparum has demonstrated the capability, through the development of multiple drug-resistant parasites, for evolutionary change. The Plasmodium species has a very high rate of replication, much higher than that actually needed to ensure transmission in the parasite's life cycle. This enables pharmaceutical treatments that are effective at reducing the reproduction rate, but not halting it, to exert a high selection pressure, thus favoring the development of resistance. The process of evolutionary change is one of the key considerations necessary when considering potential vaccine candidates. The development of resistance could cause a significant reduction in efficacy of any potential vaccine thus rendering useless a carefully developed and effective treatment.[32]

Choosing to address the symptom or the source

The parasite induces two main response types from the human immune system. These are anti-parasitic immunity and anti-toxic immunity.

- "Anti-parasitic immunity" addresses the source; it consists of an antibody response (humoral immunity) and a cell-mediated immune response. Ideally, a vaccine would enable the development of anti-plasmodial antibodies in addition to generating an elevated cell-mediated response. Potential antigens against which a vaccine could be targeted will be discussed in greater depth later. Antibodies are part of the specific immune response. They exert their effect by activating the complement cascade, stimulating phagocytic cells into endocytosis through adhesion to an external surface of the antigenic substances, thus 'marking' it as offensive. Humoral or cell-mediated immunity consists of many interlinking mechanisms that essentially aim to prevent infection entering the body (through external barriers or hostile internal environments) and then kill any micro-organisms or foreign particles that succeed in penetration. The cell-mediated component consists of many white blood cells (such as monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, basophils, mast cells, natural killer cells, and eosinophils) that target foreign bodies by a variety of different mechanisms. In the case of malaria, both systems would be targeted to attempt to increase the potential response generated, thus ensuring the maximum chance of preventing disease.

- "Anti-toxic immunity" addresses the symptoms; it refers to the suppression of the immune response associated with the production of factors that either induce symptoms or reduce the effect that any toxic by-products (of micro-organism presence) have on the development of disease. For example, it has been shown that tumor necrosis factor-alpha has a central role in generating the symptoms experienced in severe P. falciparum malaria. Thus a therapeutic vaccine could target the production of TNF-a, preventing respiratory distress and cerebral symptoms. This approach has serious limitations as it would not reduce the parasitic load; rather, it only reduces the associated pathology. As a result, there are substantial difficulties in evaluating efficacy in human trials.

Taking this information into consideration an ideal vaccine candidate would attempt to generate a more substantial cell-mediated and antibody response on parasite presentation. This would have the benefit of increasing the rate of parasite clearance, thus reducing the experienced symptoms and providing a level of consistent future immunity against the parasite.

Potential targets

| Parasite stage | Target |

|---|---|

| Sporozoite | Hepatocyte invasion; direct anti-sporozite |

| Hepatozoite | Direct anti-hepatozoite. |

| Asexual erythrocytic | Anti-host erythrocyte, antibodies blocking invasion; anti receptor ligand, anti-soluble toxin |

| Gametocytes | Anti-gametocyte. Anti-host erythrocyte, antibodies blocking fertilisation, antibodies blocking egress from the mosquito midgut. |

By their very nature, protozoa are more complex organisms than bacteria and viruses, with more complicated structures and life cycles. This presents problems in vaccine development but also increases the number of potential targets for a vaccine. These have been summarised into the life cycle stage and the antibodies that could potentially elicit an immune response.

The epidemiology of malaria varies enormously across the globe and has led to the belief that it may be necessary to adopt very different vaccine development strategies to target the different populations. A Type 1 vaccine is suggested for those exposed mostly to P. falciparum malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, with the primary objective to reduce the number of severe malaria cases and deaths in infants and children exposed to high transmission rates. The Type 2 vaccine could be thought of as a 'travelers' vaccine,' aiming to prevent all clinical symptoms in individuals with no previous exposure. This is another major public health problem, with malaria presenting as one of the most substantial threats to travelers' health. Problems with the available pharmaceutical therapies include costs, availability, adverse effects and contraindications, inconvenience, and compliance, many of which would be reduced or eliminated if an effective (greater than 85–90%) vaccine was developed.

The life cycle of the malaria parasite is particularly complex, presenting initial developmental problems. Despite the huge number of vaccines available, there are none that target parasitic infections. The distinct developmental stages involved in the life cycle present numerous opportunities for targeting antigens, thus potentially eliciting an immune response. Theoretically, each developmental stage could have a vaccine developed specifically to target the parasite. Moreover, any vaccine produced would ideally have the ability to be of therapeutic value as well as preventing further transmission and is likely to consist of a combination of antigens from different phases of the parasite's development. More than 30 of these antigens are being researched by teams all over the world in the hope of identifying a combination that can elicit immunity in the inoculated individual. Some of the approaches involve surface expression of the antigen, inhibitory effects of specific antibodies on the life cycle and the protective effects through immunization or passive transfer of antibodies between an immune and a non-immune host. The majority of research into malarial vaccines has focused on the Plasmodium falciparum strain due to the high mortality caused by the parasite and the ease of carrying out in vitro/in vivo studies. The earliest vaccines attempted to use the parasitic circumsporozoite protein (CSP). This is the most dominant surface antigen of the initial pre-erythrocytic phase. However, problems were encountered due to low efficacy, reactogenicity and low immunogenicity.

- The initial stage in the life cycle, following inoculation, is a relatively short "pre-erythrocytic" or "hepatic" phase. A vaccine at this stage must have the ability to protect against sporozoites invading and possibly inhibiting the development of parasites in the hepatocytes (through inducing cytotoxic T-lymphocytes that can destroy the infected liver cells). However, if any sporozoites evaded the immune system they would then have the potential to be symptomatic and cause the clinical disease.

- The second phase of the life cycle is the "erythrocytic" or blood phase. A vaccine here could prevent merozoite multiplication or the invasion of red blood cells. This approach is complicated by the lack of MHC molecule expression on the surface of erythrocytes. Instead, malarial antigens are expressed, and it is this towards which the antibodies could potentially be directed. Another approach would be to attempt to block the process of erythrocyte adherence to blood vessel walls. It is thought that this process is accountable for much of the clinical syndrome associated with malarial infection; therefore, a vaccine given during this stage would be therapeutic and hence administered during clinical episodes to prevent further deterioration.

- The last phase of the life cycle that has the potential to be targeted by a vaccine is the "sexual stage". This would not give any protective benefits to the individual inoculated but would prevent further transmission of the parasite by preventing the gametocytes from producing multiple sporozoites in the gut wall of the mosquito. It therefore would be used as part of a policy directed at eliminating the parasite from areas of low prevalence or to prevent the development and spread of vaccine-resistant parasites. This type of transmission-blocking vaccine is potentially very important. The evolution of resistance in the malaria parasite occurs very quickly, potentially making any vaccine redundant within a few generations. This approach to the prevention of spread is therefore essential.

- Another approach is to target the protein kinases, which are present during the entire lifecycle of the malaria parasite. Research is underway on this, yet production of an actual vaccine targeting these protein kinases may still take a long time.[33]

- Report of a vaccine candidate capable of neutralizing all tested strains of Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly form of the parasite causing malaria, was published in Nature Communications by a team of scientists from the University of Oxford in 2011.[34] The viral vector vaccine, targeting a full-length P. falciparum reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 (PfRH5) was found to induce an antibody response in an animal model. The results of this new vaccine confirmed the utility of a key discovery reported from scientists at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, published in Nature.[35] The earlier publication reported P. falciparum relies on a red blood cell surface receptor, known as 'basigin', to invade the cells by binding a protein PfRH5 to the receptor.[35] Unlike other antigens of the malaria parasite which are often genetically diverse, the PfRH5 antigen appears to have little genetic diversity. It was found to induce very low antibody response in people naturally exposed to the parasite.[34] The high susceptibility of PfRH5 to the cross-strain neutralizing vaccine-induced antibody demonstrated a significant promise for preventing malaria in the long and often difficult road of vaccine development. According to Professor Adrian Hill, a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator at the University of Oxford, the next step would be the safety tests of this vaccine. At the time (2011) it was projected that if these proved successful, the clinical trials in patients could begin within two to three years.[36]

- PfEMP1, one of the proteins known as variant surface antigens (VSAs) produced by Plasmodium falciparum, was found to be a key target of the immune system's response against the parasite. Studies of blood samples from 296 mostly Kenyan children by researchers of Burnet Institute and their cooperators showed that antibodies against PfEMP1 provide protective immunity, while antibodies developed against other surface antigens do not. Their results demonstrated that PfEMP1 could be a target to develop an effective vaccine which will reduce risk of developing malaria.[37][38]

- Plasmodium vivax is the common malaria species found in India, Southeast Asia and South America. It is able to stay dormant in the liver and reemerge years later to elicit new infections. Two key proteins involved in the invasion of the red blood cells (RBC) by P. vivax are potential targets for drug or vaccine development. When the Duffy binding protein (DBP) of P. vivax binds the Duffy antigen (DARC) on the surface of RBC, process for the parasite to enter the RBC is initiated. Structures of the core region of DARC and the receptor binding pocket of DBP have been mapped by scientists at the Washington University in St. Louis. The researchers found that the binding is a two-step process that involves two copies of the parasite protein acting together like a pair of tongs that "clamp" two copies of DARC. Antibodies that interfere with the binding by either targeting the key region of the DARC or the DBP will prevent the infection.[39][40]

- Antibodies against the Schizont Egress Antigen-1 (PfSEA-1) were found to disable the parasite's ability to rupture from the infected red blood cells (RBCs), thus preventing it from continuing with its life cycle. Researchers from Rhode Island Hospital identified Plasmodium falciparum PfSEA-1, a 244 kd malaria antigen expressed in the schizont-infected RBCs. Mice vaccinated with the recombinant PfSEA-1 produced antibodies which interrupted the schizont rupture from the RBCs and decreased the parasite replication. The vaccine protected the mice from the lethal challenge of the parasite. Tanzanian and Kenyan children who have antibodies to PfSEA-1 were found to have fewer parasites in their bloodstream and a milder case of malaria. By blocking the schizont outlet, the PfSEA-1 vaccine may work synergistically with vaccines targeting the other stages of the malaria life cycle such as hepatocyte and RBC invasion.[41][42]

Mix of antigenic components

Increasing the potential immunity generated against Plasmodia can be achieved by attempting to target multiple phases in the life cycle. This is additionally beneficial in reducing the possibility of resistant parasites developing. The use of multiple-parasite antigens can therefore have a synergistic or additive effect.

One of the most successful vaccine candidates in clinical trials consists of recombinant antigenic proteins to the circumsporozoite protein.[43]

Delivery system

The selection of an appropriate system is fundamental in all vaccine development, but especially so in the case of malaria. A vaccine targeting several antigens may require delivery to different areas and by different means in order to elicit an effective response. Some adjuvants can direct the vaccine to the specifically targeted cell type—e.g., the use of Hepatitis B virus in the RTS,S vaccine to target infected hepatocytes—but in other cases, particularly when using combined antigenic vaccines, this approach is very complex. Some methods that have been attempted include the use of two vaccines, one directed at generating a blood response and the other a liver-stage response. These two vaccines could then be injected into two different sites, thus enabling the use of a more specific and potentially efficacious delivery system.

To increase, accelerate or modify the development of an immune response to a vaccine candidate, it is often necessary to combine the antigenic substance to be delivered with an adjuvant or specialised delivery system. These terms are often used interchangeably in relation to vaccine development; however in most cases a distinction can be made. An adjuvant is typically thought of as a substance used in combination with the antigen to produce a more substantial and robust immune response than that elicited by the antigen alone. This is achieved through three mechanisms: by affecting the antigen delivery and presentation, by inducing the production of immunomodulatory cytokines, and by affecting the antigen presenting cells (APC). Adjuvants can consist of many different materials, from cell microparticles to other particulate delivery systems (e.g. liposomes).

Adjuvants are crucial in affecting the specificity and isotype of the necessary antibodies. They are thought to be able to potentiate the link between the innate and adaptive immune responses. Due to the diverse nature of substances that can potentially have this effect on the immune system, it is difficult to classify adjuvants into specific groups. In most circumstances they consist of easily identifiable components of micro-organisms that are recognised by the innate immune system cells. The role of delivery systems is primarily to direct the chosen adjuvant and antigen into target cells to attempt to increase the efficacy of the vaccine further, therefore acting synergistically with the adjuvant.

There is increasing concern that the use of very potent adjuvants could precipitate autoimmune responses, making it imperative that the vaccine is focused on the target cells only. Specific delivery systems can reduce this risk by limiting the potential toxicity and systemic distribution of newly developed adjuvants.

Studies into the efficacy of malaria vaccines developed to date have illustrated that the presence of an adjuvant is key in determining any protection gained against malaria. A large number of natural and synthetic adjuvants have been identified throughout the history of vaccine development. Options identified thus far for use combined with a malaria vaccine include mycobacterial cell walls, liposomes, monophosphoryl lipid A and squalene.

History

Individuals who are exposed to the parasite in endemic countries develop acquired immunity against disease and death. Such immunity does not, however prevent malarial infection; immune individuals often harbour asymptomatic parasites in their blood. This does, however, imply that it is possible to create an immune response that protects against the harmful effects of the parasite.

Research shows that if immunoglobulin is taken from immune adults, purified, and then given to individuals who have no protective immunity, some protection can be gained.[44]

Irradiated mosquitoes

In 1967, it was reported that a level of immunity to the Plasmodium berghei parasite could be given to mice by exposing them to sporozoites that had been irradiated by x-rays.[45] Subsequent human studies in the 1970s showed that humans could be immunized against Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum by exposing them to the bites of significant numbers of irradiated mosquitos.[46]

From 1989 to 1999, eleven volunteers recruited from the United States Public Health Service, United States Army, and United States Navy were immunized against Plasmodium falciparum by the bites of 1001–2927 mosquitoes that had been irradiated with 15,000 rads of gamma rays from a Co-60 or Cs-137 source.[47] This level of radiation is sufficient to attenuate the malaria parasites so that, while they can still enter hepatic cells, they cannot develop into schizonts nor infect red blood cells.[47] Over a span of 42 weeks, 24 of 26 tests on the volunteers showed that they were protected from malaria.[47]

References

- "Mosquirix: Opinion on medicine for use outside EU". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Malaria vaccine becomes first to achieve WHO-specified 75% efficacy goal". EurekAlert!. 23 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- Roxby P (23 April 2021). "Malaria vaccine hailed as potential breakthrough". BBC News. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- "RTS,S malaria candidate vaccine reduces malaria by approximately one-third in African infants". malariavaccine.org. Malaria Vaccine Initiative Path. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Commercial name of RTS,S". Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Foquet L, Hermsen CC, van Gemert GJ, Van Braeckel E, Weening KE, Sauerwein R, et al. (January 2014). "Vaccine-induced monoclonal antibodies targeting circumsporozoite protein prevent Plasmodium falciparum infection". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (1): 140–4. doi:10.1172/JCI70349. PMC 3871238. PMID 24292709.

- Agnandji ST, Lell B, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Methogo BG, Kabwende AL, et al. (December 2012). "A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (24): 2284–95. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208394. PMID 23136909.

- Borghino D (27 April 2015). "Malaria vaccine candidate shown to prevent thousands of cases". www.gizmag.com. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "GSK announces EU regulatory submission of malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S" (Press release). GSK. 24 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Kelland K (7 October 2013). "GSK aims to market world's first malaria vaccine". Reuters. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "First malaria vaccine receives positive scientific opinion from EMA" (Press release). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 24 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Alonso P (19 June 2019). "Letter to partners – June 2019" (Press release). Wuxi: World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "Malaria vaccine launched in Kenya: Kenya joins Ghana and Malawi to roll out landmark vaccine in pilot introduction" (Press release). Homa Bay: World Health Organization. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Davies L (6 October 2021). "WHO endorses use of world's first malaria vaccine in Africa". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- "WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk" (Press release). World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Mandavilli A (6 October 2021). "A 'Historical Event': First Malaria Vaccine Approved by W.H.O." The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Abuga, KM; Jones-Warner, W; Hafalla, JCR (February 2021). "Immune responses to malaria pre-erythrocytic stages: Implications for vaccine development". Parasite Immunology. 43 (2): e12795. doi:10.1111/pim.12795. PMC 7612353. PMID 32981095.

- Graves P, Gelband H (October 2006). "Vaccines for preventing malaria (blood-stage)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006199. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006199. PMC 6532641. PMID 17054281.

- Graves P, Gelband H (October 2006). "Vaccines for preventing malaria (pre-erythrocytic)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006198. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006198. PMC 6532586. PMID 17054280.

- Lowe D (23 April 2021). "Great Malaria Vaccine News". Science Translational Medicine. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- Datoo, Mehreen S.; Natama, Hamtandi Magloire; Somé, Athanase; Bellamy, Duncan; Traoré, Ousmane; Rouamba, Toussaint; Tahita, Marc Christian; Ido, N. Félix André; Yameogo, Prisca (7 September 2022). "Efficacy and immunogenicity of R21/Matrix-M vaccine against clinical malaria after 2 years' follow-up in children in Burkina Faso: a phase 1/2b randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00442-X. PMID 36087586. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "Malaria booster vaccine continues to meet WHO-specified 75% efficacy goal - University of Oxford". University of Oxford. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Researcher's nanoparticle key to new malaria vaccine". Research & Development. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Burkhard P, Lanar DE (2 December 2015). "Malaria vaccine based on self-assembling protein nanoparticles". Expert Review of Vaccines. 14 (12): 1525–7. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.1096781. PMC 5019124. PMID 26468608.

- "Nature report describes complete protection after 10 weeks with three doses of PfSPZ- CVac" (Press release). 15 February 2017.

- "SANARIA PfSPZ VACCINE AGAINST MALARIA RECEIVES FDA FAST TRACK DESIGNATION" (PDF). Sanaria Inc. 22 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Butler D (April 2019). "Promising malaria vaccine to be tested in first large field trial". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01232-4. PMID 32291409. S2CID 145852768.

- Graves P, Gelband H (April 2006). "Vaccines for preventing malaria (SPf66)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005966. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005966. PMC 6532709. PMID 16625647.

- Nosten, Francois (1994). "Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of SPf66 malaria vaccine in children in northwestern Thailand". The Lancet. 348 (9029): 5–8. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)04465-0. PMID 203. S2CID 54282604. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Ratanji KD, Derrick JP, Dearman RJ, Kimber I (April 2014). "Immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: influence of aggregation". Journal of Immunotoxicology. 11 (2): 99–109. doi:10.3109/1547691X.2013.821564. PMC 4002659. PMID 23919460.

- Reuters Staff (15 January 2021). "South African scientists discover new chemicals that kill malaria parasite". Reuters. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Kennedy DA, Read AF (December 2018). "Why the evolution of vaccine resistance is less of a concern than the evolution of drug resistance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (51): 12878–12886. doi:10.1073/pnas.1717159115. PMC 6304978. PMID 30559199.

- Zhang VM, Chavchich M, Waters NC (March 2012). "Targeting protein kinases in the malaria parasite: update of an antimalarial drug target". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 12 (5): 456–72. doi:10.2174/156802612799362922. PMID 22242850. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Douglas AD, Williams AR, Illingworth JJ, Kamuyu G, Biswas S, Goodman AL, et al. (December 2011). "The blood-stage malaria antigen PfRH5 is susceptible to vaccine-inducible cross-strain neutralizing antibody". Nature Communications. 2 (12): 601. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..601D. doi:10.1038/ncomms1615. PMC 3504505. PMID 22186897.

- Crosnier C, Bustamante LY, Bartholdson SJ, Bei AK, Theron M, Uchikawa M, et al. (November 2011). "Basigin is a receptor essential for erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum". Nature. 480 (7378): 534–7. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..534C. doi:10.1038/nature10606. PMC 3245779. PMID 22080952.

- Martino M (21 December 2011). "New candidate vaccine neutralizes all tested strains of malaria parasite". fiercebiotech.com. FierceBiotech. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Parish T (2 August 2012). "Lifting malaria's deadly veil: Mystery solved in quest for vaccine". Burnet Institute. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Chan JA, Howell KB, Reiling L, Ataide R, Mackintosh CL, Fowkes FJ, et al. (September 2012). "Targets of antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in malaria immunity". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 122 (9): 3227–38. doi:10.1172/JCI62182. PMC 3428085. PMID 22850879.

- Mullin E (13 January 2014). "Scientists capture key protein structures that could aid malaria vaccine design". fiercebiotechresearch.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Batchelor JD, Malpede BM, Omattage NS, DeKoster GT, Henzler-Wildman KA, Tolia NH (January 2014). "Red blood cell invasion by Plasmodium vivax: structural basis for DBP engagement of DARC". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (1): e1003869. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003869. PMC 3887093. PMID 24415938.

- Mullin E (27 May 2014). "Antigen Discovery could advance malaria vaccine". fiercebiotechresearch.com. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- Raj DK, Nixon CP, Nixon CE, Dvorin JD, DiPetrillo CG, Pond-Tor S, et al. (May 2014). "Antibodies to PfSEA-1 block parasite egress from RBCs and protect against malaria infection". Science. 344 (6186): 871–7. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..871R. doi:10.1126/science.1254417. PMC 4184151. PMID 24855263.

- Plassmeyer ML, Reiter K, Shimp RL, Kotova S, Smith PD, Hurt DE, et al. (September 2009). "Structure of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein, a leading malaria vaccine candidate". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (39): 26951–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.013706. PMC 2785382. PMID 19633296.

- "Immunoglobulin Therapy & Other Medical Therapies for Antibody Deficiencies". Immune Deficiency Foundation. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Nussenzweig RS, Vanderberg J, Most H, Orton C (October 1967). "Protective immunity produced by the injection of x-irradiated sporozoites of plasmodium berghei". Nature. 216 (5111): 160–2. Bibcode:1967Natur.216..160N. doi:10.1038/216160a0. PMID 6057225. S2CID 4283134.

- Clyde DF (May 1975). "Immunization of man against falciparum and vivax malaria by use of attenuated sporozoites". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 24 (3): 397–401. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.397. PMID 808142.

- Hoffman SL, Goh LM, Luke TC, Schneider I, Le TP, Doolan DL, et al. (April 2002). "Protection of humans against malaria by immunization with radiation-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 185 (8): 1155–64. doi:10.1086/339409. PMID 11930326.

Further reading

- Good MF, Levine MA, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA (2004). New Generation Vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-4071-9.

- Hoffman SL, Doolan DL, Richie TL (January 2004). "Malaria: a complex disease that may require a complex vaccine.". In Levine MM, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA, Good MR (eds.). New Generation Vaccines (3rd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 1763–1790. ISBN 978-0-429-15186-6.

- Good M, Kemp D. "Overview of Vaccine Strategies for Malaria". In Levine MM, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA, Good MR (eds.). ibid (3rd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-15186-6.

- Saul A. "Malaria Transmission-Blocking Vaccines". In Levine MM, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA, Good MR (eds.). New Generation Vaccines (3rd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-15186-6.

- Heppner DG, Cummings JF, Ockenhouse CF, Kester KE, Cohen J, Ballou WR (2004). "Adjuvanted RTS, S and other protein-based pre-erythrocytic stage malaria vaccines.". In Levine MM, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA, Good MR (eds.). New generation vaccines (3rd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 851–60. ISBN 978-0-429-15186-6.

- Stanisic DI, Martin LB, Good MF, Anders RF. "Plasmodium falciparum Asexual Blood Stage Vaccine Candidates: Current Status.". In Levine MM, Kaper JB, Rappuoli R, Liu MA, Good MR (eds.). New Generation Vaccines (3rd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-15186-6.

- The Jordan Report

- "Case studies: Potential malaria vaccine" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. 21 August 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- "World's largest malaria vaccine trial now underway in seven African countries" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. 3 November 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- Abdulla S, Oberholzer R, Juma O, Kubhoja S, Machera F, Membi C, et al. (December 2008). "Safety and immunogenicity of RTS,S/AS02D malaria vaccine in infants" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (24): 2533–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807773. PMID 19064623. S2CID 21873677.

- Aponte JJ, Aide P, Renom M, Mandomando I, Bassat Q, Sacarlal J, et al. (November 2007). "Safety of the RTS,S/AS02D candidate malaria vaccine in infants living in a highly endemic area of Mozambique: a double blind randomised controlled phase I/IIb trial". Lancet. 370 (9598): 1543–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61542-6. PMID 17949807. S2CID 19372191.

- Bejon P, Lusingu J, Olotu A, Leach A, Lievens M, Vekemans J, et al. (December 2008). "Efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine against malaria in children 5 to 17 months of age". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (24): 2521–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807381. PMC 2655100. PMID 19064627.

- Delves PJ, Roitt IM (2001). Roitt's essential immunology. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-05902-7.

- Gurunathan S, Klinman DM, Seder RA (2000). "DNA vaccines: immunology, application, and optimization*". Annual Review of Immunology. 18: 927–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.927. PMID 10837079.

- Schwartz L, Brown GV, Genton B, Moorthy VS (January 2012). "A review of malaria vaccine clinical projects based on the WHO rainbow table". Malaria Journal. 11: 11. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-11. PMC 3286401. PMID 22230255.

- Waters A (February 2006). "Malaria: new vaccines for old?". Cell. 124 (4): 689–93. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.011. PMID 16497579.

External links

- "Malaria Vaccines". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Malaria Vaccine Initiative

- Malaria vaccines UK

- Gates Foundation Global Health: Malaria