Afamelanotide

Afamelanotide, sold under the brand name Scenesse, is a synthetic peptide and analogue of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone. It has been used to prevent skin damage from the sun in people with erythropoietic protoporphyria in the European Union since January 2015 and the United States since October 2019. As a medication, it is administered in subcutaneous implant form. Each implant lasts two months.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌæfəmɛˈlænoʊtaɪd/ ( |

| Trade names | Scenesse |

| Other names | [Nle4,D-Phe7]α-MSH; NDP-α-MSH; NDP-MSH; Melanotan; Melanotan-1; Melanotan I; EPT1647; CUV1647; |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous; intramuscular; intravenous; subcutaneous implant; intranasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 30 minutes[1] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C78H111N21O19 |

| Molar mass | 1646.874 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers it to be a first-in-class medication.[2]

Medical use

Afamelanotide is used in the European Union to prevent phototoxicity in adults with erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).[1][3]

Adverse effects

Very common (may affect more than 10% of people) adverse effects in people with EPP include headache and nausea. Common (between 1% and 10%) adverse effects include back pain, upper respiratory tract infections, decreased appetite, migraine, dizziness, weakness, fatigue, lethargy, sleepiness, feeling hot, stomach pain, diarrhea, vomiting, flushing and red skin, development of warts, spots and freckles, itchy skin, and reactions at the injection site. There are many uncommon (less than 1%) adverse effects.[1]

Pharmacology

Afamelanotide is thought to cause skin to darken by binding to the melanocortin 1 receptor which in turn drives melanogenesis.[1]

Afamelanotide has a half-life of 30 minutes. After the implant is injected, most of the drug is released within the first two days, with 90% released by the fifth day. By the tenth day no drug is detectable in plasma.[1]

Its metabolites, distribution, metabolism and excretion were not understood as of 2017.[1]

Chemistry

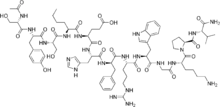

The amino acid sequence is Ac-Ser-Tyr-Ser-Nle-Glu-His-D-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys-Pro-Val-NH2. It is additionally known as [Nle4,D-Phe7]-α-MSH, which is sometimes abbreviated as NDP-MSH or NDP-α-MSH. Afamelanotide is the International Nonproprietary Name.[4]

History

After the isolation and primary structure determination of a-MSH in the 1950s, many investigators initiated studies into the synthesis of this peptide. The role of α-MSH in promoting melanin diffusion has been known since the 1960s.[5] In the 1980s, teams at the University of Arizona started to synthesise more potent analogs of a-MSH, including afamelanotide, which they initially named melano-tan (or melanotan-I) due to its ability to tan skin with minimal sun exposure, and later synthesised melanotan-II.[6][7][8][9]

Following initial development at the University of Arizona as a sunless tanning agent; the Australian company Clinuvel conducted further clinical trials in that and other indications, and brought the drug to market in the European Union, the United States, and Australia.

To pursue the tanning agent, melanotan-I was licensed by Competitive Technologies, a technology transfer company operating on behalf of University of Arizona, to an Australian startup called Epitan,[10][9] which changed its name to Clinuvel in 2006.[11]

Early clinical trials showed that the peptide had to be injected about ten times a day due to its short half-life, so the company collaborated with Southern Research in the US to develop a depot formulation that would be injected under the skin, and release the peptide slowly. This was done by 2004.[10]

As of 2010, afamelanotide was in Phase III trials for erythropoietic protoporphyria and polymorphous light eruption and was in Phase II trials for actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma; as well, it had been trialled in phototoxicity associated with systemic photodynamic therapy and solar urticaria.[12] Clinuvel had also obtained orphan drug status for afamelanotide in the US and the EU by that time.[12]

In May 2010, the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA, or Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco) approved afamelanotide as a treatment for erythropoietic protoporphyria.[13]

In January 2015, afamelanotide was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe for the treatment of phototoxicity in people with EPP.[1]

There were three trials that evaluated afamelanotide in those with erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).[14]

In Trial 1, subjects received afamelanotide or vehicle implant every two months and were followed for 180 days.[14] Subjects recorded every day the number of hours spent in direct sunlight and whether they experienced any phototoxic pain that day.[14] The trial measured the total number of hours over 180 days spent in direct sunlight between 10 am and 6 pm on days with no pain.[14]

In Trial 2, subjects received afamelanotide or vehicle implants every two months and were followed for 270 days.[14] Subjects daily recorded the number of hours spent outdoors as well as whether "most of the day" was spent in direct sunlight, shade, or a combination of both, and whether they experienced any phototoxic pain that day.[14] The trial measured the total number of hours over 270 days spent outdoors between 10 am and 3 pm on days with no pain for which "most of the day" was spent in direct sunlight.[14]

In Trial 3 subjects were randomized to receive a total of three afamelanotide or vehicle implants administered subcutaneously every two months and were followed for 180 days.[14] Data from this trial were used primarily for assessment of side effects.[14]

The FDA approved afamelanotide based on evidence from three clinical trials (Trial 1/ NCT 01605136, Trial 2/ NCT00979745 and Trial 3/ NCT01097044) of 244 adults 18–74 years of age with EPP.[14] The trials were conducted at 22 sites in the US and Europe.[14]

In October 2019, afamelanotide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a medicine to reduce pain caused by light exposure (particularly sunlight) as experienced by people with erythropoietic protoporphyria.[15][14]

Society and culture

Usage in general public

A number of products are sold online and in gyms and beauty salons as "melanotan" or "melanotan-1" which discuss afamelanotide in their marketing.[16][17][18]

Without a prescription, these drugs are not legally sold in many jurisdictions and are potentially dangerous.[19][20][21][22]

Starting in 2007, health agencies in various countries began issuing warnings against their use.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Unlicensed and untested powders sold as "melanotan" are found on the Internet (marketed for tanning and other purposes). Multiple regulatory bodies have warned consumers that the peptides may be unsafe and ineffective.

Research

Ongoing research is underway for other skin disorders. Afamelanotide causes skin to turn darker by causing skin to produce more melanin.

References

- "Scenesse: Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 27 January 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2017. For updates see EMA Index page

- "New Drug Therapy Approvals 2019". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "Scenesse". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- Baker BI (May 1993). "The role of melanin-concentrating hormone in color change". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 680 (1): 279–89. Bibcode:1993NYASA.680..279B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb19690.x. PMID 8390154. S2CID 11465789.

- Sawyer, T K; Sanfilippo, P J; Hruby, V J; Engel, M H; Heward, C B; Burnett, J B; Hadley, M E (October 1980). "4-Norleucine, 7-D-phenylalanine-alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone: a highly potent alpha-melanotropin with ultralong biological activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (10): 5754–5758. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.5754S. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.10.5754. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 350149. PMID 6777774.

- En-Ling, Lan (1992). "Preformulation studies of melanotan-II" (PDF). University of Arizona; Campus Respositories.

- Al-Obeidi, Fahad; Castrucci, Ana M. de L.; Hadley, Mac E.; Hruby, Victor J. (December 1989). "Potent and prolonged-acting cyclic lactam analogs of .alpha.-melanotropin: design based on molecular dynamics". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 32 (12): 2555–2561. doi:10.1021/jm00132a010. ISSN 0022-2623. PMID 2555512.

- Hadley ME, Dorr RT (April 2006). "Melanocortin peptide therapeutics: historical milestones, clinical studies and commercialization". Peptides. 27 (4): 921–30. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2005.01.029. PMID 16412534. S2CID 21025287.

- "EpiTan focuses on Melanotan, a potential blockbuster". The Pharma Letter. 1 November 2004.

- "Epitan changes name to Clinuvel, announces new clinical program". LabOnline. 27 February 2006.

- Dean T (3 May 2010). "Biotechnology profile: Bright future for Clinuvel (ASX:CUV)". Australian Life Scientist. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017.

- "Gazzetta Ufficiale: Sommario". Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata. 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Drug Trials Snapshots: Scenesse". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 8 October 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "FDA approves first treatment to increase pain-free light exposure in patients with a rare disorder" (Press release). 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Believe It Or Not 'Tanorexia' A Very Real Problem". WCBS-TV, CBS. 20 May 2009. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Fools Gold". Cosmopolitan (Australia). 14 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Madrigal, Alexis (29 January 2009). "Suntan Drug Greenlighted for Trials". Wired. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- "Tanning drug a health risk". Herald Sun. 31 October 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- Langan EA, Nie Z, Rhodes LE (September 2010). "Melanotropic peptides: more than just 'Barbie drugs' and 'sun-tan jabs'?". The British Journal of Dermatology. 163 (3): 451–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09891.x. PMID 20545686. S2CID 8203334.

- Langan EA, Ramlogan D, Jamieson LA, Rhodes LE (January 2009). "Change in moles linked to use of unlicensed "sun tan jab"". BMJ. 338: b277. doi:10.1136/bmj.b277. PMID 19174439. S2CID 27838904.

- "Risky tan jab warnings 'ignored'". BBC News Online. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- "Warning against the product Melanotan". Danish Medicines Agency. 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ""Tan jab" is an unlicensed medicine and may not be safe" (Press release). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- "US Lab Research Inc Warning letter". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Melanotan Powder for Injection". Notice Information: – Warning – 27 February 2009. Irish Medicines Board. 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- "Legemiddelverket advarer mot bruk av Melanotan". Norwegian Medicines Agency. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- "Melanotan – farlig og ulovlig brunfarge". Norwegian Medicines Agency. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

External links

- "Afamelanotide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Afamelanotide acetate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.