Pelvic inflammatory disease

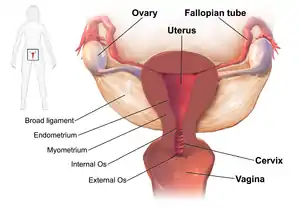

Pelvic inflammatory disease, also known as pelvic inflammatory disorder (PID), is an infection of the upper part of the female reproductive system, namely the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, and inside of the pelvis.[5][2] Often, there may be no symptoms.[1] Signs and symptoms, when present, may include lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, fever, burning with urination, pain with sex, bleeding after sex, or irregular menstruation.[1] Untreated PID can result in long-term complications including infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and cancer.[2][3][4]

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pelvic inflammatory disorder |

| |

| Drawing showing the usual sites of infection in pelvic inflammatory disease | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, fever, burning with urination, pain with sex, irregular menstruation[1] |

| Complications | Infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, cancer[2][3][4] |

| Causes | Bacteria that spread from the vagina and cervix[5] |

| Risk factors | Gonorrhea, chlamydia[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, ultrasound, laparoscopic surgery[2] |

| Prevention | Not having sex, having few sexual partners, using condoms[6] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[7] |

| Frequency | 1.5 percent of young women yearly[8] |

The disease is caused by bacteria that spread from the vagina and cervix.[5] Infections by Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis are present in 75 to 90 percent of cases.[2] Often, multiple different bacteria are involved.[2] Without treatment, about 10 percent of those with a chlamydial infection and 40 percent of those with a gonorrhea infection will develop PID.[2][9] Risk factors are generally similar to those of sexually transmitted infections and include a high number of sexual partners and drug use.[2] Vaginal douching may also increase the risk.[2] The diagnosis is typically based on the presenting signs and symptoms.[2] It is recommended that the disease be considered in all women of childbearing age who have lower abdominal pain.[2] A definitive diagnosis of PID is made by finding pus involving the fallopian tubes during surgery.[2] Ultrasound may also be useful in diagnosis.[2]

Efforts to prevent the disease include not having sex or having few sexual partners and using condoms.[6] Screening women at risk for chlamydial infection followed by treatment decreases the risk of PID.[10] If the diagnosis is suspected, treatment is typically advised.[2] Treating a woman's sexual partners should also occur.[10] In those with mild or moderate symptoms, a single injection of the antibiotic ceftriaxone along with two weeks of doxycycline and possibly metronidazole by mouth is recommended.[7] For those who do not improve after three days or who have severe disease, intravenous antibiotics should be used.[7]

Globally, about 106 million cases of chlamydia and 106 million cases of gonorrhea occurred in 2008.[9] The number of cases of PID, however, is not clear.[8] It is estimated to affect about 1.5 percent of young women yearly.[8] In the United States, PID is estimated to affect about one million people each year.[11] A type of intrauterine device (IUD) known as the Dalkon shield led to increased rates of PID in the 1970s.[2] Current IUDs are not associated with this problem after the first month.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms in PID range from none to severe. If there are symptoms, fever, cervical motion tenderness, lower abdominal pain, new or different discharge, painful intercourse, uterine tenderness, adnexal tenderness, or irregular menstruation may be noted.[2][1][12][13]

Other complications include endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, pelvic peritonitis, periappendicitis, and perihepatitis.[14]

Complications

PID can cause scarring inside the reproductive system, which can later cause serious complications, including chronic pelvic pain, infertility, ectopic pregnancy (the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in adult females), and other complications of pregnancy.[15] Occasionally, the infection can spread to the peritoneum causing inflammation and the formation of scar tissue on the external surface of the liver (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome).[16]

Cause

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are usually the main cause of PID. Data suggest that PID is often polymicrobial.[14] Isolated anaerobes and facultative microorganisms have been obtained from the upper genital tract. N. gonorrhoeae has been isolated from fallopian tubes, facultative and anaerobic organisms were recovered from endometrial tissues.[17][18]

The anatomical structure of the internal organs and tissues of the female reproductive tract provides a pathway for pathogens to ascend from the vagina to the pelvic cavity thorough the infundibulum. The disturbance of the naturally occurring vaginal microbiota associated with bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of PID.[17]

N. gonorrhoea and C. trachomatis are the most common organisms. The least common were infections caused exclusively by anaerobes and facultative organisms. Anaerobes and facultative bacteria were also isolated from 50 percent of the patients from whom Chlamydia and Neisseria were recovered; thus, anaerobes and facultative bacteria were present in the upper genital tract of nearly two-thirds of the PID patients.[17] PCR and serological tests have associated extremely fastidious organism with endometritis, PID, and tubal factor infertility. Microorganisms associated with PID are listed below.[17]

Rarely cases of PID have developed in people who have stated they have never had sex.[19]

Bacteria

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Prevotella spp.

- Streptococcus pyogenes

- Prevotella bivia

- Prevotella disiens

- Bacteroides spp.

- Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus

- Peptostreptococcus anaerobius

- Gardnerella vaginalis

- Escherichia coli

- Group B streptococcus

- α-hemolytic streptococcus

- Coagulase-negative staphylococcus

- Atopobium vaginae

- Acinetobacter spp.

- Dialister spp.

- Fusobacterium gonidiaformans

- Gemella spp.

- Leptotrichia spp.

- Mogibacterium spp.

- Porphyromonas spp.

- Sphingomonas spp.

- Veillonella spp.[17]

- Cutibacterium acnes

- Mycoplasma genitalium[18][20]

- Mycoplasma hominis

- Ureaplasma spp.[14]

Diagnosis

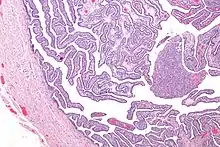

Upon a pelvic examination, cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness will be experienced.[5] Mucopurulent cervicitis and or urethritis may be observed. In severe cases more testing may be required such as laparoscopy, intra-abdominal bacteria sampling and culturing, or tissue biopsy.[14][21]

Laparoscopy can visualize "violin-string" adhesions, characteristic of Fitz-Hugh–Curtis perihepatitis and other abscesses that may be present.[21]

Other imaging methods, such as ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic imaging (MRI), can aid in diagnosis.[21] Blood tests can also help identify the presence of infection: the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), the C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and chlamydial and gonococcal DNA probes.[14][21]

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), direct fluorescein tests (DFA), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) are highly sensitive tests that can identify specific pathogens present. Serology testing for antibodies is not as useful since the presence of the microorganisms in healthy people can confound interpreting the antibody titer levels, although antibody levels can indicate whether an infection is recent or long-term.[14]

Definitive criteria include histopathologic evidence of endometritis, thickened filled Fallopian tubes, or laparoscopic findings. Gram stain/smear becomes definitive in the identification of rare, atypical and possibly more serious organisms.[22] Two thirds of patients with laparoscopic evidence of previous PID were not aware they had PID, but even asymptomatic PID can cause serious harm.

Laparoscopic identification is helpful in diagnosing tubal disease; a 65 percent to 90 percent positive predictive value exists in patients with presumed PID.[23]

Upon gynecologic ultrasound, a potential finding is tubo-ovarian complex, which is edematous and dilated pelvic structures as evidenced by vague margins, but without abscess formation.[24]

Differential diagnosis

A number of other causes may produce similar symptoms including appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhagic or ruptured ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, and endometriosis and gastroenteritis, peritonitis, and bacterial vaginosis among others.[2]

Pelvic inflammatory disease is more likely to reoccur when there is a prior history of the infection, recent sexual contact, recent onset of menses, or an IUD (intrauterine device) in place or if the partner has a sexually transmitted infection.[25]

Acute pelvic inflammatory disease is highly unlikely when recent intercourse has not taken place or an IUD is not being used. A sensitive serum pregnancy test is typically obtained to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Culdocentesis will differentiate hemoperitoneum (ruptured ectopic pregnancy or hemorrhagic cyst) from pelvic sepsis (salpingitis, ruptured pelvic abscess, or ruptured appendix).[26]

Pelvic and vaginal ultrasounds are helpful in the diagnosis of PID. In the early stages of infection, the ultrasound may appear normal. As the disease progresses, nonspecific findings can include free pelvic fluid, endometrial thickening, uterine cavity distension by fluid or gas. In some instances the borders of the uterus and ovaries appear indistinct. Enlarged ovaries accompanied by increased numbers of small cysts correlates with PID.[26]

Laparoscopy is infrequently used to diagnose pelvic inflammatory disease since it is not readily available. Moreover, it might not detect subtle inflammation of the fallopian tubes, and it fails to detect endometritis.[27] Nevertheless, laparoscopy is conducted if the diagnosis is not certain or if the person has not responded to antibiotic therapy after 48 hours.

No single test has adequate sensitivity and specificity to diagnose pelvic inflammatory disease. A large multisite U.S. study found that cervical motion tenderness as a minimum clinical criterion increases the sensitivity of the CDC diagnostic criteria from 83 percent to 95 percent. However, even the modified 2002 CDC criteria do not identify women with subclinical disease.[28]

Prevention

Regular testing for sexually transmitted infections is encouraged for prevention.[29] The risk of contracting pelvic inflammatory disease can be reduced by the following:

- Using barrier methods such as condoms; see human sexual behaviour for other listings.[30]

- Seeking medical attention if you are experiencing symptoms of PID.[30]

- Using hormonal combined contraceptive pills also helps in reducing the chances of PID by thickening the cervical mucosal plug & hence preventing the ascent of causative organisms from the lower genital tract.[30]

- Seeking medical attention after learning that a current or former sex partner has, or might have had a sexually transmitted infection.[30]

- Getting a STI history from your current partner and strongly encouraging they be tested and treated before intercourse.[30]

- Diligence in avoiding vaginal activity, particularly intercourse, after the end of a pregnancy (delivery, miscarriage, or abortion) or certain gynecological procedures, to ensure that the cervix closes.[30]

- Reducing the number of sexual partners.[25]

- Sexual monogamy.[31]

- Abstinence[30]

Treatment

Treatment is often started without confirmation of infection because of the serious complications that may result from delayed treatment. Treatment depends on the infectious agent and generally involves the use of antibiotic therapy although there is no clear evidence of which antibiotic regimen is more effective and safe in the management of PID.[32] If there is no improvement within two to three days, the patient is typically advised to seek further medical attention. Hospitalization sometimes becomes necessary if there are other complications. Treating sexual partners for possible STIs can help in treatment and prevention.[10]

For women with PID of mild to moderate severity, parenteral and oral therapies appear to be effective.[33][34] It does not matter to their short- or long-term outcome whether antibiotics are administered to them as inpatients or outpatients.[35] Typical regimens include cefoxitin or cefotetan plus doxycycline, and clindamycin plus gentamicin. An alternative parenteral regimen is ampicillin/sulbactam plus doxycycline. Erythromycin-based medications can also be used.[36] A single study suggests superiority of azithromycin over doxycycline.[32] Another alternative is to use a parenteral regimen with ceftriaxone or cefoxitin plus doxycycline.[25] Clinical experience guides decisions regarding transition from parenteral to oral therapy, which usually can be initiated within 24–48 hours of clinical improvement.[27]

Prognosis

Even when the PID infection is cured, effects of the infection may be permanent. This makes early identification essential. Treatment resulting in cure is very important in the prevention of damage to the reproductive system. Formation of scar tissue due to one or more episodes of PID can lead to tubal blockage, increasing the risk of the inability to get pregnant and long-term pelvic/abdominal pain.[37] Certain occurrences such as a post pelvic operation, the period of time immediately after childbirth (postpartum), miscarriage or abortion increase the risk of acquiring another infection leading to PID.[25]

Epidemiology

Globally about 106 million cases of chlamydia and 106 million cases of gonorrhea occurred in 2008.[9] The number of cases of PID; however, is not clear.[8] It is estimated to affect about 1.5 percent of young women yearly.[8] In the United States PID is estimated to affect about one million people yearly.[11] Rates are highest with teenagers and first time mothers. PID causes over 100,000 women to become infertile in the US each year.[38][39]

References

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Clinical Manifestations and Sequelae". cdc.gov. October 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- Mitchell, C; Prabhu, M (December 2013). "Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 27 (4): 793–809. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.08.004. PMC 3843151. PMID 24275271.

- Chang, A. H.; Parsonnet, J. (2010). "Role of Bacteria in Oncogenesis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (4): 837–857. doi:10.1128/CMR.00012-10. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2952975. PMID 20930075.

- Chan, Philip J.; Seraj, Ibrahim M.; Kalugdan, Theresa H.; King, Alan (1996). "Prevalence of Mycoplasma Conserved DNA in Malignant Ovarian Cancer Detected Using Sensitive PCR–ELISA". Gynecologic Oncology. 63 (2): 258–260. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0316. ISSN 0090-8258. PMID 8910637.

- Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J (2015). "Pelvic inflammatory disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (21): 2039–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1411426. PMID 25992748.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Patient Counseling and Education". Centers for Disease Control. October 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "2010 STD Treatment Guidelines Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Centers for Disease Control. August 15, 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- Eschenbach, D (2008). "Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Glob. Libr. Women's Med. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10029 (inactive 31 July 2022). ISSN 1756-2228.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - World Health Organization (2012). "Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections - 2008" (PDF). who.int. pp. 2, 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Partner Management and Public Health Measures". Centers for Disease Control. October 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Self-Study STD Modules for Clinicians — Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Next Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Your Online Source for Credible Health Information CDC Home Footer Separator Rectangle Epidemiology". Centers for Disease Control. October 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- Kumar, Ritu; Bronze, Michael Stuart (2015). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Empiric Therapy". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Zakher, Bernadette; Cantor MD, Amy G.; Daeges, Monica; Nelson MD, Heidi (December 16, 2014). "Review: Screening for Gonorrhea and Chlamydia: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Prevententive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (12): 884–894. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.6232. doi:10.7326/M14-1022. PMID 25244000. S2CID 207538182.

- Ljubin-Sternak, Suncanica; Mestrovic, Tomislav (2014). "Review: Chlamydia trachonmatis and Genital Mycoplasmias: Pathogens with an Impact on Human Reproductive Health". Journal of Pathogens. 2014 (183167): 183167. doi:10.1155/2014/183167. PMC 4295611. PMID 25614838.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease - CDC Fact Sheet". www.cdc.gov. 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". MedScape. March 27, 2014. Archived from the original on March 13, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- Sharma H, Tal R, Clark NA, Segars JH (2014). "Microbiota and pelvic inflammatory disease". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 32 (1): 43–9. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1361822. PMC 4148456. PMID 24390920.

- Lis, R.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Manhart, L. E. (2015). "Mycoplasma genitalium Infection and Female Reproductive Tract Disease: A Meta-Analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 61 (3): 418–26. doi:10.1093/cid/civ312. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 25900174.

- Cho, Hyun-Woong; Koo, Yu-Jin; Min, Kyung-Jin; Hong, Jin-Hwa; Lee, Jae-Kwan (2015). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Virgin Women with Tubo-ovarian Abscess: A Single-center Experience and Literature Review". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 30 (2): 203–208. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.001. ISSN 1083-3188. PMID 26260586.

- Wiesenfeld, HC; Manhart, LE (15 July 2017). "Mycoplasma genitalium in Women: Current Knowledge and Research Priorities for This Recently Emerged Pathogen". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 216 (suppl_2): S389–S395. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix198. PMC 5853983. PMID 28838078.

- Moore MD, Suzanne (Mar 27, 2014). Rivlin MD, Michel (ed.). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Medscape, Drugs and Diseases, Background. Medscape. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- Andreoli, Thomas E.; Cecil, Russell L. (2001). Cecil Essentials Of Medicine (5th ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. ISBN 9780721681795.

- DeCherney, Alan H.; Nathan, Lauren (2003). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780838514016.

- Wasco, Emily; Lieberman, Gillian (October 17, 2003). "Tuboovarian complex" (PDF). Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". CDC Fact Sheet. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- Hoffman, Barbara (2012). Williams gynecology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 42. ISBN 9780071716727.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, 2010 STD Treatment Guidelines". CDC. January 28, 2011. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- Blenning, CE; Muench, J; Judkins, DZ; Roberts, KT (2007). "Clinical inquiries. Which tests are most useful for diagnosing PID?". J Fam Pract. 56 (3): 216–20. PMID 17343812.

- Smith, KJ; Cook, RL; Roberts, MS (2007). "Time from sexually transmitted infection acquisition to pelvic inflammatory disease development: influence on the cost-effectiveness of different screening intervals". Value in Health. 10 (5): 358–66. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00189.x. PMID 17888100.

- "Prevention — STD Information from CDC". Center For Disease Control. June 5, 2015. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- Reichard, Ulrich H. (2003). "Monogamy: past and present". In Reichard, Ulrich H.; Boesch, Christophe (eds.). Monogamy: Mating Strategies and Partnerships in Birds, Humans and Other Mammals. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-0-521-52577-0. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03.

- Savaris, Ricardo F.; Fuhrich, Daniele G.; Maissiat, Jackson; Duarte, Rui V.; Ross, Jonathan (20 August 2020). "Antibiotic therapy for pelvic inflammatory disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD010285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010285.pub3. hdl:10183/180267. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8094882. PMID 32820536.

- Ness, RB; Hillier, SL; Kip, KE (2004). "Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease". Obstet Gynecol. 4 (Supp 3): S111–22. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000139512.37582.17. PMID 15458899. S2CID 32444872.

- Smith, KJ; Ness, RB; Wiesenfeld, HC (2007). "Cost-effectiveness of alternative outpatient pelvic inflammatory disease treatment strategies". Sex Transm Dis. 34 (12): 960–6. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000225321.61049.13. PMID 18077847. S2CID 31500831.

- Walker, CK; Wiesenfeld, HC (2007). "Antibiotic therapy for acute pelvic inflammatory disease: the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines". Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 (Suppl 3): S111–22. doi:10.1086/511424. PMID 17342664.

- "Erythromycin" (PDF). Davis. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-10. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Center For Disease Control. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Center For Disease Control. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- Sutton, MY; Sternberg, M; Zaidi, A; t Louis, ME; Markowitz, LE (December 2005). "Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985–2001". Sex Transm Dis. 32 (12): 778–84. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000175375.60973.cb. PMID 16314776. S2CID 6424987.