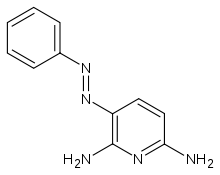

Phenazopyridine

Phenazopyridine is a medication which, when excreted by the kidneys into the urine, has a local analgesic effect on the urinary tract. It is often used to help with the pain, irritation, or urgency caused by urinary tract infections, surgery, or injury to the urinary tract. Phenazopyridine was discovered by Bernhard Joos, the founder of Cilag.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pyridium |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682231 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.149 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H11N5 |

| Molar mass | 213.244 g·mol−1 |

| | |

Medical uses

Phenazopyridine is prescribed for its local analgesic effects on the urinary tract. It is sometimes used in conjunction with an antibiotic or other anti-infective medication at the beginning of treatment to help provide immediate symptomatic relief. Phenazopyridine does not treat infections or injury; it is only used for symptom relief.[1][2] It is recommended that it be used for no longer than the first two days of antibacterial treatment as longer treatment may mask symptoms.[2]

Phenazopyridine is also prescribed for other cases requiring relief from irritation or discomfort during urination. For example, it is often prescribed after the use of an in-dwelling Foley catheter, endoscopic (cystoscopy) procedures, or after urethral, prostate, or urinary bladder surgery which may result in irritation of the epithelial lining of the urinary tract.[1]

This medication is not used to treat infection and may mask symptoms of inappropriately treated UTI. It provides symptom relief during a UTI, following surgery, or injury to the urinary tract. UTI therapy should be limited to 1–2 days.[2] Long-term use of phenazopyridine can mask symptoms.[3]

Side effects

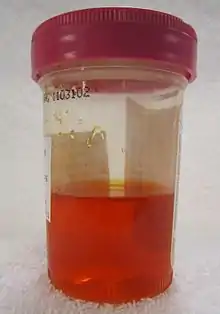

Phenazopyridine produces a vivid color change in urine, typically to a dark orange to reddish color. This effect is common and harmless, and indeed a key indicator of the presence of the medication in the body. Users of phenazopyridine are warned not to wear contact lenses, as phenazopyridine has been known to permanently discolor contact lenses and fabrics.[1][4] It also tends to leave an orange-yellow stain on surfaces it comes in contact with. Some may be mistakenly concerned that this indicated blood in the urine.

Phenazopyridine can also cause headaches, upset stomach (especially when not taken with food), or dizziness. Less frequently it can cause a pigment change in the skin or eyes, to a noticeable yellowish color. This is due to a depressed excretion via the kidneys causing a buildup of the medication in the skin, and normally indicates a need to discontinue usage.[2] Other such side effects include fever, confusion, shortness of breath, skin rash, and swelling of the face, fingers, feet, or legs.[1][2] Long-term use may cause yellowing of nails.[5]

Phenazopyridine should be avoided by people with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency,[2][6][7][8] because it can cause hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells) due to oxidative stress.[9] It has been reported to cause methemoglobinemia after overdose and even normal doses.[10] In at least one case the patient had pre-existing low levels of methemoglobin reductase,[11] which likely predisposed her to the condition. It has also been reported to cause sulfhemoglobinemia.[2][12][13] [14]

Phenazopyridine is an azo dye.[15][16] Other azo dyes, which were previously used in textiles, printing, and plastic manufacturing, have been implicated as carcinogens that can cause bladder cancer.[17] While phenazopyridine has never been shown to cause cancer in humans, evidence from animal models suggests that it is potentially carcinogenic.[2][18]

Pregnancy

This medication is pregnancy category B. This means that the medication has shown no adverse events in animal models, but no human trials have been conducted.[2] It is not known if phenazopyridine is excreted in breast milk.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

The full pharmacokinetic properties of phenazopyridine have not been determined. It has mostly been studied in animal models, but they may not be very representative of humans.[19] Rat models have shown its half-life to be 7.35 hours,[20] and 40% is metabolized hepatically (by the liver).[20]

Mechanism of action

Phenazopyridine's mechanism of action is not well known, and only basic information on its interaction with the body is available. It is known that the chemical has a direct topical analgesic effect on the mucosa lining of the urinary tract. It is rapidly excreted by the kidneys directly into the urine.[19] Hydroxylation is the major form of metabolism in humans,[19] and the azo bond is usually not cleaved.[19] On the order of 65% of an oral dose will be secreted directly into the urine chemically unchanged.[2]

Brand names

In addition to its generic form, phenazopyridine is distributed under the following brand names:

- Azo-Maximum Strength

- Azo-Standard

- Baridium

- Nefrecil

- Phenazalgin

- Phenazodine

- Pyridiate

- Pyridium

- Pyridium Plus

- Sedural

- Uricalm

- Uristat

- Uropyrine

- Urodine

- Urogesic

- Urovit

References

- "Pyridium Plus® Tablets" (PDF). Warner Chilcott. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "PYRIDIUM (phenazopyridine) tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Wang, Alina; Nizran, Parminder; Malone, Michael; Riley, Timothy (September 2013). "Urinary Tract Infections". Primary Care - Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (3): 693. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.06.005. PMC 1983013. PMID 5776230.

- "Phenazopyridine: MedlinePlus Drug Information". Medline plus. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Amit, G; Halkin, A (15 December 1997). "Lemon-yellow nails and long-term phenazopyridine use". Annals of Internal Medicine (letter). 127 (12): 1137. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00040. PMID 9412335. S2CID 41928972.

- Tishler, M; Abramov, A (1983). "Phenazopyridine-induced hemolytic anemia in a patient with G6PD deficiency". Acta Haematol. 70 (3): 208–9. doi:10.1159/000206727. PMID 6410650.

- Galun E, Oren R, Glikson M, Friedlander M, Heyman A (November 1987). "Phenazopyridine-induced hemolytic anemia in G-6-PD deficiency". Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 21 (11): 921–2. doi:10.1177/106002808702101116. PMID 3678069. S2CID 7262697.

- Mercieca JE, Clarke MF, Phillips ME, Curtis JR (4 Sep 1982). "Acute hemolytic anaemia due to phenazopyridine hydrochloride in G-6-PD deficient subject". Lancet. 2 (8297): 564. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90651-1. PMID 6125724. S2CID 27340450.

- Frank JE (October 2005). "Diagnosis and management of G6PD deficiency". American Family Physician. 72 (7): 1277–82. PMID 16225031.

- Jeffery WH; Zelicoff AP; Hardy WR. (February 1982). "Acquired methemoglobinemia and hemolytic anemia after usual doses of phenazopyridine". Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 16 (2): 57–9. doi:10.1177/106002808201600212. PMID 7075467. S2CID 20968675.

- Daly JS, Hultquist DE, Rucknagel DL (August 1983). "Phenazopyridine induced methaemoglobinaemia associated with decreased activity of erythrocyte cytochrome b5 reductase". Journal of Medical Genetics. 20 (4): 307–9. doi:10.1136/jmg.20.4.307. PMC 1049126. PMID 6620333.

- Halvorsen, SM; Dull, WL (September 1991). "Phenazopyridine-induced sulfhemoglobinemia: inadvertent rechallenge". American Journal of Medicine. 91 (3): 315–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(91)90135-K. PMID 1892154.

- Kermani TA, Pislaru SV, Osborn TG (April 2009). "Acrocyanosis from phenazopyridine-induced sulfhemoglobinemia mistaken for Raynaud phenomenon". Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 15 (3): 127–9. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e31819db6db. PMID 19300288.

- Gopalachar AS, Bowie VL, Bharadwaj P (June 2005). "Phenazopyridine-induced sulfhemoglobinemia". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 39 (6): 1128–30. doi:10.1345/aph.1E557. PMID 15886294. S2CID 22812461.

- Cystitis in Females~treatment at eMedicine

- "Phenazopyridine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- Transitional Cell Carcinoma Imaging at eMedicine

- "Phenazopyridine Hydrochloride" (PDF). Report on Carcinogens, Twelfth Edition (2011). National Toxicology Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Thomas BH, Whitehouse LW, Solomonraj G, Paul CJ (April 1990). "Excretion of phenazopyridine and its metabolites in the urine of humans, rats, mice, and guinea pigs". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 79 (4): 321–5. doi:10.1002/jps.2600790410. PMID 2352143.

- Jurima-Romet M, Thomas BH, Solomonraj G, Paul CJ, Huang H (March 1993). "Metabolism of phenazopyridine by isolated rat hepatocytes". Biopharm Drug Dispos. 14 (2): 171–9. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510140208. PMID 8453026. S2CID 29419875.

External links

- Information about phenazopyridine from the US National Library of Medicine

- Interstitial Cystitis Association

- American Urological Association