Problematic smartphone use

Problematic smartphone use is proposed by some researchers to be a form of psychological or behavioral dependence on cell phones, closely related to other forms of digital media overuse such as social media addiction or internet addiction disorder. Other researchers have stated that terminology relating to behavioral addictions in regards to smartphone use can cause additional problems both in research and stigmatization of users, suggesting the term to evolve to problematic smartphone use.[1] Problematic use can include preoccupation with mobile communication, excessive money or time spent on mobile phones, and use of mobile phones in socially or physically inappropriate situations such as driving an automobile. Increased use can also lead to adverse effects on relationships, mental or physical health, and ensues anxiety if separated from a mobile phone or sufficient signal. Preschool children and young adults are at highest risk for problematic smartphone use.[2]

The use of smartphone significantly increased since the late 2000s. In 2019 conducts, global smartphone users penetrated in 41.5% of total population. Due to prolific technological advance, the smartphone overuse continued to be a major threat in Asian countries such as China, with around 700 million users are registered in 2018. Digital media overuse tangentially linked to ocular problems, especially in young age. It has been estimated that 49.8% (4.8 billion) of global population with digital media overuse would be affected with myopia by 2050.[3]

History and terminology

It is also known as smartphone overuse, smartphone addiction, mobile phone overuse, or cell phone dependency. Founded in current research on the adverse consequences of overusing technology, "mobile phone overuse" has been proposed as a subset of forms of "digital addiction", or "digital dependence", reflecting increasing trends of compulsive behaviour amongst users of technological devices.[4] Researchers have variously termed these behaviours "smartphone addiction" and "problematic smartphone use", as well as referring to use of non-smartphone mobile devices (cell phones).[5] Forms of technology addiction have been considered as diagnoses since the mid 1990s.[6] Panova and Carbonell published a review in 2018 that specifically encouraged terminology of "problematic use" in regard to technology behaviours, rather than continuing research based on other behavioral addictions.[1]

Unrestrained use of technological devices may affect developmental, social, mental and physical well-being and result in symptoms akin to other behavioral addictions.[7] However, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has not formally codified smartphone overuse as a diagnosis.[8] Gaming disorder has been recognised in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).[9][10] Varied, changing recommendations are in part due to the lack of well established evidence or expert consensus, the differing emphasis of the classification manuals, as well as difficulties utilising animal models for behavioral addictions.[11]

Whilst published studies have shown associations between digital media use and mental health symptoms or diagnoses, causality has not been established, with nuances and caveats of researchers often misunderstood by the general public, or misrepresented by the media.[12] A systematic review of reviews published in 2019 concluded that evidence, although of mainly low to moderate quality, showed an association of screen time with poorer psychological health including symptoms such as inattention, hyperactivity, low self esteem, and behavioral issues in childhood and adolescence.[13] Several studies have shown that females are more likely to overuse social media, and males video games.[14][15] This has led experts to suggest that digital media overuse may not be a unified phenomenon, with some calling to delineate proposed disorders based on individual online activity.[14]

Due to the lack of recognition and consensus on the concepts, diagnoses and treatments are difficult to standardise or recommend, especially considering that "new media has been subject to such moral panic."[16]

Prevalence

International estimates of the prevalence of forms of technology overuse have varied considerably, with marked variations by nation[17][18] and increases over time.[19]

Prevalence of mobile phone overuse depends largely on definition and thus the scales used to quantify a subject's behaviors. Two main scales are in use, the 20-item self-reported Problematic Use of Mobile Phones (PUMP) scale,[20] and the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (MPPUS), which have been used both with adult and adolescent populations. There are variations in the age, gender, and percentage of the population affected problematically according to the scales and definitions used. The prevalence among British adolescents aged 11–14 was 10%.[21] In India, addiction is stated at 39-44% for this age group.[22] Under different diagnostic criteria, the estimated prevalence ranges from 0 to 38%, with self-attribution of mobile phone addiction exceeding the prevalence estimated in the studies themselves.[23] The prevalence of the related problem of Internet addiction was 4.9-10.7% in Korea, and is now regarded as a serious public health issue.[24] A questionnaire survey in Korea also found that these teenagers are twice as likely to admit that they are "mobile phone addicted" as adults. For most teenagers, smartphone communication is what they think is an important way to maintain social relationships and has become an important part of their lives.[25] Additional scales used to measure smartphone addictions are the Korean Scale for Internet Addiction for adolescents (K-scale), the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV), and the Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale (SAPS). These implicit tests were validated as means of measuring smartphone and internet addiction in children and adolescents in a study conducted by Daeyoung Roh, Soo-Young Bhang, Jung-Seok Choi, Yong Sil Kweon, Sang-Kyu Lee and Marc N. Potenza.[26]

Behaviors associated with mobile-phone addiction differ between genders.[27][28] Older people are less likely to develop addictive mobile phone behavior because of different social usage, stress, and greater self-regulation.[29] At the same time, the study by media regulator Ofcom has shown that 50% of 10-year-olds in the UK owned a smartphone in 2019.[30] These children who grow with gadgets in their hands are more prone to mobile phone addiction, since their online and offline worlds merge into a single whole.

Effects

Overuse of mobile phones may be associated with negative outcomes on mental and physical health, in addition to having an impact on how users interact socially.[31][32]

Social

Some people are replacing face-to-face conversations with cyber ones. Clinical psychologist Lisa Merlo says, "Some patients pretend to talk on the phone or fiddle with apps to avoid eye contact or other interactions at a party."[33] Furthermore,

- 70% check their phones in the morning within an hour of getting up.

- 56% check their phones before going to bed.

- 48% check their phones over the weekend.

- 51% constantly check their phones during vacation.

- 44% reported they would feel very anxious and irritable if they did not interact with their phones within a week.[34]

This change in style from face-to-face to text-based conversation has also been observed by Sherry Turkle. Her work cites connectivity as an important trigger of social behavior change regarding communication;[32] therefore, this adaptation of communicating is not caused only by the phone itself. In her book, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, Turkle argues that people now find themselves in a state of "continual co-presence."[35] This means that digital communication allows the occurrence of two or more realities in the same place and time. Subsequently, person also live in a "world of continual partial attention,"[35] the process of paying simultaneous attention to a number of sources of incoming information, but at a superficial level. Bombarded with an abundance of emails, texts, messages, people not only find themselves divesting people of their human characteristics or individuality, but also increasingly treating them as digital units. This is often referred to as depersonalization.[36]

According to Elliot Berkman, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon, the constant checking of phones is caused by reward learning and the fear of missing out. Berkman explains that, “Habits are a product of reinforcement learning, one of our brain's most ancient and reliable systems,” and people tend, thus, to develop habits of completing behaviors that have rewarded them in the past.[37] For many, using mobile phone has been enjoyable in the past, leading to feel excited and positive when receive a notification from phones. Berkman also iterates that people often check their smartphones to relieve the social pressure they place upon themselves to never miss out on exciting things. As Berkman says, "Smartphones can be an escape from boredom because they are a window into many worlds other than the one right in front of you, helping us feel included and involved in society."[37] When people do not check their mobile phones, they are unable to satisfy this “check habit” or suppress the fear of missing out, leading to feel anxious and irritable. A survey conducted by Hejab M. Al Fawareh and Shaidah Jusoh also found that people also often feel incomplete without their smartphones. Of the 66 respondents, 61.41% strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “I feel incomplete when my smartphone is not with me.”[38]

Other implications of cell phone use in mental health symptoms were observed by Thomée et al. in Sweden. This study found a relationship between report of mental health and perceived stress of participants' accessibility, which is defined as the possibility to be disturbed at any moment of day or night.[31]

Critics of smartphones have especially raised concerns about effects on youth.[39] The presence of smartphones in everyday life may affect social interactions amongst teenagers. Present evidence shows that smartphones are not only decreasing face-to-face social interactions between teenagers, but are also making the youth less likely to talk to adults.[40] In a study produced by Doctor Lelia Green at Edith Cowan University, researchers discovered that, “the growing use of mobile technologies implies a progressive digital colonization of children’s lives, reshaping the interactions of younger adults.” Face-to-face interactions have decreased because of the increase in shared interactions via social media, mobile video sharing, and digital instant messaging. Critics believe the primary concern in this shift is that the youth are inhibiting themselves of constructive social interactions and emotional practices.[41] Engaging in a strictly digital world may isolate individuals, causing lack of social and emotional development.

Other studies show that there is actually a positive social aspect from smartphone use. A study on whether smartphone presence changed responses to social stress conducted an experiment with 148 males and females around the age of 20.[42] Participants were split up into 3 groups where 1) phone was present and use was encouraged, 2) phone was present with use restricted, and 3) no phone access. They were exposed to a peer, social-exclusion stressor, and saliva samples measuring levels of alpha-amylase (sAA), or stressor hormones, were measured throughout. The results showed that both of the phone-present groups had lower levels of SAA and cortisol than the group without a phone, thus suggesting that the presence of a smartphone, even if it's not being used, can decrease the negative effects of social exclusion.[42]

Health

Research from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine at Queen Mary in 2011 indicated that one in six cell phones is contaminated with fecal matter. Under further inspection, some of the phones with the fecal matter were also harboring lethal bacteria such as E. coli, which can result in fever, vomiting, and diarrhea.[43]

According to the article Mobile Phones and Nosocomial Infections, written by researchers at Mansoura University of Egypt, it states that the risk of transmitting the bacteria by the medical staff (who carry their cellphones during their shift) is much higher because cellphones act as a reservoir where the bacteria can thrive.[44][45]

Despite the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization stating in 2011 that radio frequency is a possible human carcinogen, based on heavy usage increasing the risk of developing glioma tumors.[46], no relationship has been established. In fact, there is no definitive evidence linking cancer and phone use, nor any accepted scientific explanation for how phone usage could cause cancer.[47] Despite this, research is continuing based on leads from changing patterns of mobile phone use over time and habits of phone users,[48] and there been claims that low-level radio frequency radiation promotes tumors in mice.[49]

Studies show that some users associate mobile phone usage with headaches, impaired memory and concentration, fatigue, dizziness and disturbed sleep.[50] Claims that users have developed electrosensitivity from excessive exposure to electromagnetic fields are likely psychological in origin due to the nocebo effect.[51][52] Minor acute immediate effects of radio frequency exposure have long been known such as the Microwave auditory effect which was discovered in 1962.[53]

A study by scientists from the Karolinska Institute and Uppsala University in Sweden and from Wayne State University in Michigan founded that using a cell phone before bed can cause insomnia. The study[54] showed that this is due to the radiation received by the user as stated, "The study indicates that during laboratory exposure to 884 MHz wireless signals, components of sleep believed to be important for recovery from daily wear and tear are adversely affected." Additional adverse health effects attributable to smartphone usage include a diminished quantity and quality of sleep due to an inhibited secretion of melatonin.[55]Adolescents who spent time online before bedtime had higher rates of Internet addiction and insomnia than those who did not spend time online before bedtime.[56]

In 2014, 58% of World Health Organization states advised the general population to reduce radio frequency exposure below heating guidelines. The most common advice is to use hands-free kits (69%), to reduce call time (44%), use text messaging (36%), avoid calling with low signals (24%) or use phones with low specific absorption rate (SAR) (22%).[57] In 2015 Taiwan banned toddlers under the age of two from using mobile phones or any similar electronic devices, and France banned Wi-Fi from toddlers' nurseries.[58]

As the market increases to grow, more light is being shed upon the accompanying behavioral health issues and how mobile phones can be problematic. Mobile phones continue to become increasingly multifunctional and sophisticated, which this in turn worsens the problem.[59]

According to optician Andy Hepworth, blue violet light, a light that is transmitted from the cell phone into the eye is potentially hazardous and can be "toxic" to the back of the eye. He states that an over exposure to blue violet light can lead to a greater risk of macular degeneration which is a leading cause of blindness.[60]

Psychological

There are concerns that some mobile phone users incur considerable debt, and that mobile phones are being used to violate privacy and harass others.[61] In particular, there is increasing evidence that mobile phones are being used as a tool by children to bully other children.[62]

There is a large amount of research on mobile phone use, and its positive and negative influence on the human's psychological mind, mental health and social communication. Mobile phone users may encounter stress, sleep disturbances and symptoms of depression, especially young adults.[63] Consistent phone use can cause a chain reaction, affecting one aspect of a user's life and expanding to contaminate the rest. It usually starts with social disorders, which can lead to depression and stress and ultimately affect lifestyle habits such as sleeping right and eating right.[31]

According to research done by Professor of psychology at San Diego State University Jean M. Twenge, there is a correlation between mobile phone overuse and depression. In the wake of smartphone being evolved, Twenge and her colleagues stated that there was also an increase seen in depressive symptoms and even suicides among adolescents in 2010.[63] The theory behind this research is that adolescents who are being raised as a generation of avid smartphone users are spending so much time on these devices that they forgo actual human interaction which is seen as essential to mental health, "The more time teens spend looking at screens, the more likely they are to report symptoms of depression."[64] While children used to spend their free time outdoors with others, with the advancement of technology, this free time is seemingly now being spent more on mobile devices.

In this research, Twenge also discusses that, three out of four American teens owned an iPhone and with this rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed since 2011 which follows the release of the iPhone in 2007 and the iPad in 2010.[41] Another focus is that teens now spend the majority of their leisure time on their phones. This leisure time can be seen as detrimental which can be seen through eighth-graders who spend 10 or more hours a week on social media are 56% more likely to be unhappy than those who devote less time to social media.[41]

Psychologist Nancy Colier has argued that people have lost sight of what is truly important to them in life. She says that people have become "disconnected from what really matters, from what makes us feel nourished and grounded as human beings."[65] People's addiction to technology has deterred neurological and relationship development because tech is being introduced to people at a very young age. People have become so addicted to their phones that they are almost dependent on them. Humans are not meant to be constantly staring at a screen as time is needed to relax their eyes and more importantly their minds. Colier states: "Without open spaces and downtime, the nervous system never shuts down—it's in constant fight-or-flight mode. We're wired and tired all the time. Even computers reboot, but we’re not doing it."[65]

The amount of time spent on screens appears to have a correlation with happiness levels. A nationally representative study of American 12th graders funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse titled Monitoring the Future Survey found that “teens who spent more time than average on screen activities are more likely to be unhappy, and those who spend more time than average on non-screen activities are more likely to be happy.” One of the most important findings of this study is how the amount of time spent on non screen activities versus on screen activities affects the happiness levels of teenagers.[63]

However, while it is easy to see a correlation between cell phone overuse and these symptoms of depression, anxiety, and isolation, it is much harder to prove that cell phones themselves cause these issues. Studies of correlations cannot prove causation because there are multiple other factors that increase depression in people today. According to psychologist Peter Etchells, although parents and other figures share these concerns other possible variables must be reviewed as well. Etchells proposes two possible alternative theories: depression could cause teens to use iPhones more or teens could be more open to discussing the topic of depression in this day and age.[66]

A survey done by a group of independent opticians reviled that 43% of people under the age of 25 experienced anxiety or even irritation when they were not able to access their phone whenever they wanted.[60] This survey shows the psychological effect that cell phones have on people, specifically young people.

Neural

There has been considerable speculation about the impact problematic mobile usage may have on cognitive development and how such habits could be ‘rewiring’ the brains of those highly engaged with their mobiles. Research has shown that the reward areas of the brains of those who use their phones more exhibit different structural connectivity than those who use their phones less.[67] Further findings have linked digital media behaviors to the brain's self-regulatory control structures, suggesting that variation in individuals' ability to control behavioral impulses might also be a key psychological pathway connecting mobile technology habits to the brain.[68]

Distracted driving

Research has found that there is a direct relationship between mobile phone overuse and mobile phone use while driving.[69] Mobile phone overuse can be especially dangerous in certain situations such as texting/browsing and driving or talking on the phone while driving.[70][71][72] Over 8 people are killed and 1,161 are injured daily because of distracted driving.[73] At any given daylight moment across U.S., approximately 660,000 drivers are using cell phones or electronic devices while driving.[73] The significant number of injuries and accidents from distracted driving can be contributed at least partially to mobile phone overuse. However, many cell phone-related crashes are not reported due to drivers' reluctance to admit texting or talking behind the wheel.[74] There is currently no national ban on texting while driving, but many states have implemented laws to try to prevent these accidents.[73]

Sixteen states as well as Washington D.C., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands passed laws prohibiting the use of hand-held devices while driving. Texting and driving is banned in most of the country; new drivers in 38 states and DC are not permitted to use cell phones behind the wheel. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, or NHTSA (which promotes safe driving through research and education), drivers between the ages of 16 and 24 were most distracted, with women at greater risk of dying in a crash. About 20,000 of motor vehicle fatalities between 2012 and 2017 were related to distracted driving.

In the UK, the only way to currently use a mobile phone lawfully whilst driving is using a hands-free system. Any other type of phone use whilst in control of a vehicle, whether stationary or moving, carries a fine of £1, 000 and 6 penalty points. This can be increased for serious misuse. 1 in 5 of UK residents admit to checking social media whilst being behind the wheel.[75] It's interesting to note that in the UK, it is also illegal for someone accompanying a learner driver to use their mobile phone whilst driving. As an instructor, they are classed as in control of the vehicle, even if they are not a professional instructor.

A text can take one's eyes off the road for an average of five seconds. Although brief, one driving at 55 mph can travel the length of a football field in that time. Approximately three percent of drivers are talking on the phone when stopped at an intersection. Furthermore, five percent of drivers are on the phone at any given time. The Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS) reported those who used cell phones more often tended to brake harder, drive faster, and change lanes more frequently, predisposing them to crashes and near-crashes. They are also two to six times more likely to get into an accident.

Research indicates driver performance is adversely affected by concurrent cell phone use, delaying reaction time and increasing lane deviations and length of time with eyes off the road. It can also cause "inattention blindness," in which drivers see but do not register what is in front of them.

Teen drivers are especially at risk. About 1.2 million and 341,000 crashes in 2013 involved talking and texting, respectively. Distractions such as music, games, GPS, social media, etc., are potentially deadly when combined with inexperience. The dangers of driving and multitasking continue to rise as more technology is integrated into cars. Teens who texted more frequently were less likely to wear a seat belt and more likely to drive intoxicated or ride with a drunk driver. Cell phone use can reduce brain activity as much as 37%, affecting young drivers' abilities to control their vehicles, pay attention to the roadway, and respond promptly to traffic events.

Tools to prevent or treat mobile phone overuse

The following tools or interventions can be used to prevent or treat mobile phone overuse.

Behavioral

Many studies have found relationships between psychological or mental health issues and smartphone addiction.[76][77][78][79] Hence, behavioral interventions such as individual or family psychotherapy for these issues may help. In fact, studies have found that psychotherapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing are able to successfully treat internet addiction and may be useful for mobile phone overuse.[80][81] Further, support groups and family therapy may also help prevent and treat internet and smartphone addiction.[82]

Complete abstinence from mobile phone use or abstinence from certain apps can also help treat mobile phone overuse.[82][83] Other behavioral interventions include practicing the opposite (e.g. disrupt their normal routine and re-adapt to new time patterns of use), goal-setting, reminder cards (e.g. listing 5 problems resulting from mobile phone overuse and 5 benefits of limiting overuse), and creating a personal inventory of alternative activities (e.g. exercise, music, art).[80][82]

In 2019 the World Health Organization issued recommendations about active lifestyle, sleep and screen time for children at age 0–5. The recommendations are:

For children in age less than one year: 30 minute physical activity, 0 hours screen time and 14 – 17 hours of sleep time per day.

For children in age 1 year: 180 minutes physical activity, 0 hours screen time, 11–14 hours of sleep time per day.

For children in age 2 year: 180 minutes physical activity, 1 hour screen time, 11–14 hours of sleep time per day.

For 3-4-year-old children: 180 minutes physical activity, 1 hour screen time, 10–13 hours of sleep time per day.[84]

Phone settings

Many smartphone addiction activists (such as Tristan Harris) recommend turning one's phone screen to grayscale mode, which helps reduce time spent on mobile phones by making them boring to look at.[85] Other phone settings alterations for mobile phone non-use included turning on airplane mode, turning off cellular data and/or Wi-Fi, turning off the phone, removing specific apps, and factory resetting.[86]

Phone apps

German psychotherapist and online addiction expert Bert te Wildt recommends using apps such as Offtime and Menthal to help prevent mobile phone overuse.[87] In fact, there are many apps available on Android and iOS stores which help track mobile usage. For example, in iOS 12 Apple added a function called "Screen Time" that allows users to see how much time they have spent on the phone. In Android a similar feature called "digital wellbeing" has been implemented to keep track of cell phone usage.[88] These apps usually work by doing one of two things: increasing awareness by sending user usage summaries, or notifying the user when he/she has exceeded some user-defined time-limit for each app or app category.

Research-based

Studying and developing interventions for temporary mobile phone non-use is a growing area of research. Hiniker et al. generated 100 different design ideas for mobile phone non-use belonging to eight organic categories: information (i.e. agnostically providing information to the user about his or her behavior), reward (i.e. rewarding the user for engaging in behaviors that are consistent with his or her self-defined goals), punishment (i.e. punishing the user for engaging in behaviors that are inconsistent with his or her self-defined goals), disruption (i.e. a temporary barrier momentarily prevents the user from engaging in a specific behavior), limit (i.e. certain behaviors are time or context-bound or otherwise constrained within defined parameters), mindfulness (i.e. the user is asked to reflect on his or her choices, before, during or after making them), appeal to values (i.e. reminding the user about the underlying values that shaped his or her decisions about de- sired use and non-use), social support (i.e. opportunities for including other individuals into the intervention).

Users found interventions related to information, limit, and mindfulness to be the most useful. The researchers implement an Android app that combined these three intervention types and found that users reduced their time with the apps they feel are a poor use of time by 21% while their use of the apps they feel are a good use of time remained unchanged.[89]

AppDetox allows users to define rules that limit their usage of specific apps.[90] PreventDark detects and prevents problematic usage of smartphones in the dark.[91] Using vibrations instead of notifications to limit app usage has also been found to be effective.[92] Further, researchers have found group-based interventions that rely on users sharing their limiting behaviors with others to be effective.[93]

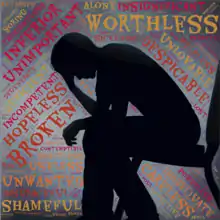

Psychological symptoms of phone usage

The psychological symptoms that people who are addicted to smartphones possession are depression, social isolation, low self-esteem and anxiety.[96] Three types of disorders classified as follows: (1) Depression is a medical illness that adversely influences people in emotion, imagination, and action. It is the common word related to the mental problem accredited by clinical psychologists. It is the symptom that people possess a lot offline, however, the number of people gets in online these days. (2) Social isolation—the lack of interaction between individuals and society. If the communications are just done by the message on the phone, the conversation with face-to-face would no longer happen and the offline real-life friends would not be made or resisted anymore. People may think they are happy and satisfying their life, however, only online. Therefore, they would end up people feeling lonely and isolated from the world when they are in real life. (3) low self-esteem and anxiety are a lack of confidence and feeling negative about oneself. People check the reaction to their posts and care about likes, comments, and other's post, which decreases self-esteem. These connect to anxiety; caring other's reaction to show off themselves, checking phone frequently with no reason.[97] It has been acknowledged that problematic smartphone use affects quality of life (QOL) parameters. For example, it was found that the user awareness mode while using the device affects the QOL parameters in various ways.[98]

Depression

Depressive symptoms, in particular, are some of the most serious psychological problems in adolescents; the relationship between depressive symptoms and mobile phone addiction is a critical issue because such symptoms may lead to substance abuse, school failure, and even suicide.[99][100] Depression caused by phone addiction can result in failure of the entire life. For example, if the person is diagnosed with depression, they start to compare themselves with others. A person would curse other beings if everyone expected him/her to be in good fortune and well-being. Furthermore, the person may remind him/her failure of everything, convincing not to succeed at all costs.

Isolation

The increase of mobile phone addiction levels would increase user's social isolation from a decrease of face-to-face social interactions, then users would face much more interpersonal problems.[99] The phone stops the conversation and interaction between humans. The process of smartphone overuse may negatively affects social support and undermines user's psychological health. Some indirect evidence also exist. For example, Lemmens, Valkenburg, and Peter (2011) founded that behavioral addiction (i.e. gambling) with mobile phone overuse may leads to loneliness, causing conflict with family or friends, and potentially reducing social support.[101]

Low self-esteem and anxiety

The other psychological symptoms that are caused by phone addiction are self-esteem and anxiety. Today, Social Network Service (SNS) is one of the main streams in the world, therefore it dissolved a lot in daily life too. Studies with teens have consistently shown that there are significant relationships between high extroversion, high anxiety, low self-esteem, and mobile phone usage. The stronger the young person's mobile phone addiction, the more likely that individual is to have high mobile phone call time, receive excessive calls, and receive excessive text messages.[99]

Anxious people more easily perceive certain normal life matters as pressure. To reduce this stress might result in even more addictive behaviors and females are more likely to use mobile phones to maintain social relations.[99]

Moreover, online, under the name anonymous, people utilize it in bad ways like the cyberbully or spread rumors. People also force their opinions and post bad comments that might hurt others too. All of these examples would result in people by having a symptom of anxiety and low self-esteem that connects to depression.

See also

- Computer addiction

- De Quervain syndrome

- Digital detox, a period of time during which a person refrains from using electronic connecting devices

- Digital media use and mental health

- Instagram's impact on people

- Internet addiction disorder

- Mobile phone § Health effects

- Mobile phone radiation and health

- Mobile phones and driving safety

- Nomophobia, a proposed name for the fear of being out of cellular phone contact

- Smartphone zombie

- Television addiction

- Video game overuse

References

- Panova, Tayana; Carbonell, Xavier (June 2018). "Is smartphone addiction really an addiction?". Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 7 (2): 252–259. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.49. ISSN 2062-5871. PMC 6174603. PMID 29895183.

- Csibi, Sándor; Griffiths, Mark D.; Demetrovics, Zsolt; Szabo, Attila (1 June 2021). "Analysis of Problematic Smartphone Use Across Different Age Groups within the 'Components Model of Addiction'". International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 19 (3): 616–631. doi:10.1007/s11469-019-00095-0. ISSN 1557-1882. S2CID 162184024.

- Wang, Jian; Li, Mei; Zhu, Daqiao; Cao, Yang (8 December 2020). "Smartphone Overuse and Visual Impairment in Children and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 22 (12): e21923. doi:10.2196/21923. PMC 7755532. PMID 33289673.

- Rubio, Gabriel; Rodríguez de Fonseca, Fernando; De-Sola Gutiérrez, José (2016). "Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 7: 175. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5076301. PMID 27822187.

- Elhai, Jon D.; Dvorak, Robert D.; Levine, Jason C.; Hall, Brian J. (January 2017). "Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology". Journal of Affective Disorders. 207: 251–259. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030. PMID 27736736. S2CID 205642153.

- Young, Kimberly (27 February 1998). Caught in the net : how to recognize the signs of Internet addiction--and a winning strategy for recovery. New York, New York. ISBN 978-0471191599. OCLC 38130573.

- Chamberlain, Samuel R.; Grant, Jon E. (August 2016). "Expanding the definition of addiction: DSM-5 vs. ICD-11". CNS Spectrums. 21 (4): 300–303. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000183. ISSN 2165-6509. PMC 5328289. PMID 27151528.

- "Internet Gaming". www.psychiatry.org. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Gaming disorder". Gaming disorder. World Health Organization. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Grant, Jon E.; Chamberlain, Samuel R. (1 August 2016). "Expanding the definition of addiction: DSM-5 vs. ICD-11". CNS Spectrums. 21 (4): 300–303. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000183. ISSN 1092-8529. PMC 5328289. PMID 27151528.

- Kardefelt-Winther, Daniel (1 February 2017). "How does the time children spend using digital technology impact their mental well-being, social relationships and physical activity? - An evidence-focused literature review" (PDF). UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Viner, Russell M.; Stiglic, Neza (1 January 2019). "Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews". BMJ Open. 9 (1): e023191. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 6326346. PMID 30606703.

- Hawi, Nazir; Samaha, Maya (30 August 2019). "Identifying commonalities and differences in personality characteristics of Internet and social media addiction profiles: traits, self-esteem, and self-construal". Behaviour & Information Technology. 38 (2): 110–119. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1515984. ISSN 0144-929X. S2CID 59523874.

- Griffiths, Mark D.; Kuss, Daria J. (17 March 2017). "Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (3): 311. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030311. PMC 5369147. PMID 28304359.

- Ryding, Francesca C.; Kaye, Linda K. (2018). ""Internet Addiction": a Conceptual Minefield". International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 16 (1): 225–232. doi:10.1007/s11469-017-9811-6. ISSN 1557-1874. PMC 5814538. PMID 29491771.

- De-Sola Gutiérrez, José; Rodríguez de Fonseca, Fernando; Rubio, Gabriel (24 October 2016). "Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 7: 175. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175. PMC 5076301. PMID 27822187.

- Cheng, Cecilia; Li, Angel Yee-lam (1 December 2014). "Internet Addiction Prevalence and Quality of (Real) Life: A Meta-Analysis of 31 Nations Across Seven World Regions". Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 17 (12): 755–760. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0317. ISSN 2152-2715. PMC 4267764. PMID 25489876.

- Olson, Jay A.; Sandra, Dasha A.; Colucci, Élissa S.; Al Bikaii, Alain; Chmoulevitch, Denis; Nahas, Johnny; Raz, Amir; Veissière, Samuel P. L. (1 April 2022). "Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries". Computers in Human Behavior. 129: 107138. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107138. ISSN 0747-5632. S2CID 245159672.

- Merlo LJ, Stone AM, Bibbey A (2013). "Measuring Problematic Mobile Phone Use: Development and Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the PUMP Scale". J Addict. 2013: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2013/912807. PMC 4008508. PMID 24826371.

- Lopez-Fernandez O, Honrubia-Serrano L, Freixa-Blanxart M, Gibson W (2014). "Prevalence of problematic mobile phone use in British adolescents" (PDF). Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 17 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0260. hdl:2445/53130. PMID 23981147.

- Davey S, Davey A (2014). "Assessment of Smartphone Addiction in Indian Adolescents: A Mixed Method Study by Systematic-review and Meta-analysis Approach". J Prev Med. 5 (12): 1500–1511. PMC 4336980. PMID 25709785.

- Pedrero Pérez EJ, Rodríguez Monje MT, Ruiz Sánchez De León JM (2012). "Mobile phone abuse or addiction. A review of the literature". Adicciones. 24 (2): 139–152. PMID 22648317.

- Koo HJ, Kwon JH (2014). "Risk and protective factors of internet addiction: a meta-analysis of empirical studies in Korea". Yonsei Med J. 55 (6): 1691–1711. doi:10.3349/ymj.2014.55.6.1691. PMC 4205713. PMID 25323910.

- Kim, Dongil; Lee, Yunhee; Lee, Juyoung; Nam, JeeEun Karin; Chung, Yeoju (21 May 2014). "Development of Korean Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale for Youth". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e97920. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...997920K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097920. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4029762. PMID 24848006.

- Roh, Daeyoung, et al. “The Validation of Implicit Association Test Measures for Smartphone and Internet Addiction in at-Risk Children and Adolescents.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions, vol. 7, no. 1, 2018, pp.79–87, https://go-gale-com.ezproxy2.library.drexel.edu/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=drexel_main&id=GALE%7CA534488412&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon.

- Roberts JA, Yaya LH, Manolis C (2014). "The invisible addiction: cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students". Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 3 (4): 254–265. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.015. PMC 4291831. PMID 25595966.

- Ioannidis, Konstantinos; Treder, Matthias S.; Chamberlain, Samuel R.; Kiraly, Franz; Redden, Sarah A.; Stein, Dan J.; Lochner, Christine; Grant, Jon E. (1 June 2018). "Problematic internet use as an age-related multifaceted problem: Evidence from a two-site survey". Addictive Behaviors. 81: 157–166. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.017. ISSN 0306-4603. PMC 5849299. PMID 29459201.

- van Deursen AJAM; Bolle CL; Hegner SM; Kommers PAM (2015). "Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behaviour: The role of smartphone usage types, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, age, and gender". Computers in Human Behavior. 45: 411–420. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.039.

- "Half of UK 10-year-olds own a smartphone". BBC News. 4 February 2020.

- Thomée, Sara; Härenstam, Annika; Hagberg, Mats (2011). "Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults - a prospective cohort study". BMC Public Health. 11 (1): 66. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-66. PMC 3042390. PMID 21281471.

- Turkle, Sherry (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from each Other. New York: Basic Books. p. 241. ISBN 9780465010219.

- Gibson, E. (27 July 2011). Smartphone dependency: a growing obsession with gadgets. Retrieved 27 September 2013 from USA Today website: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/medical/health/medical/mentalhealth/story/2011/07/Smartphone-dependency-a-growing-obsession-to-gadgets/49661286/1

- Perlow, Leslie A. (2012). Sleeping with your smartphone : how to break the 24/7 habit and change the way you work. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. ISBN 9781422144046.

- Turkle, Sherry (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books. pp. 161. ISBN 9780465010219.

- "the definition of depersonalize". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Baral, Susmita (4 January 2017). "How to Break the Habit of Checking your Phone all the Time". Mic. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Al Fawareh, Hejab M. (6 November 2017). "The Use and Effects of Smartphones in Higher Education". International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies. 11 (6): 103–111. doi:10.3991/ijim.v11i6.7453.

- Gardner, Howard; Davis, Katie (22 October 2013). The App Generation: How Today's Youth Navigate Identity, Intimacy, and Imagination in a Digital World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19621-4.

- Chan, Nee Nee; Walker, Caroline; Gleaves, Alan (1 March 2015). "An exploration of students' lived experiences of using smartphones in diverse learning contexts using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach" (PDF). Computers & Education. 82: 96–106. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.001. ISSN 0360-1315.

- Twenge, Story by Jean M. "Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Hunter, John F.; Hooker, Emily D.; Rohleder, Nicolas; Pressman, Sarah D. (May 2018). "The Use of Smartphones as a Digital Security Blanket: The Influence of Phone Use and Availability on Psychological and Physiological Responses to Social Exclusion". Psychosomatic Medicine. 80 (4): 345–352. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000568. ISSN 0033-3174. PMID 29521885. S2CID 3784504.

- Britt, Darice (June 2013). "Health Risks of Using Mobile Phones". South Carolina University. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Badr, Rawia Ibrahim; Badr, Hatem Ibrahim; Ali, Nabil Mansour (2012). "Mobile phones and nosocomial infections". International Journal of Infection Control. 8 (2). doi:10.3396/ijic.v8i2.014.12. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Badr, Rawia Ibrahim; Badr, Hatem ibrahim; Ali, Nabil Mansour (26 March 2012). "Mobile phones and nosocomial infections". International Journal of Infection Control. 8 (2). doi:10.3396/ijic.v8i2.014.12.

- World Health Organization: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2011). "IARC Classifies radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as possibly carcinogenic to humans" (PDF). Press Release No. 208.

- "Do mobile phones, 4G or 5G cause cancer?". 20 December 2019.

- Sinhna, Kounteya (18 May 2010). "Cell overuse can cause brain cancer". The Times of India. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Lerchl A, Klose M, Grote K, Wilhelm AF, Spathmann O, Fiedler T, Streckert J, Hansen V, Clemens M (April 2015). "Tumor promotion by exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields below exposure limits for humans". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 459 (4): 585–90. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.151. PMID 25749340.

- Al-Khlaiwi T, Meo SA (2004). "Association of mobile phone radiation with fatigue, headache, dizziness, tension and sleep disturbance in Saudi population". Saudi Med. J. 25 (6): 732–736. PMID 15195201.

- Carpenter DO (2014). "Excessive Exposure to Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields May Cause the Development of Electrohypersensitivity". Altern Ther Health Med. 20 (6): 40–42. PMID 25478802.

- Rubin, G. James; Hahn, Gareth; Everitt, Brian S.; Cleare, Anthony J.; Wessely, Simon (13 April 2006). "Are some people sensitive to mobile phone signals? Within participants double blind randomised provocation study". BMJ. 332 (7546): 886–891. doi:10.1136/bmj.38765.519850.55. PMC 1440612. PMID 16520326.

- Frey AH (1962). "Human auditory system response to modulated electromagnetic energy". J Appl Physiol. 17 (4): 689–692. doi:10.1152/jappl.1962.17.4.689. PMID 13895081. S2CID 12359057.

- Arnetz, Bengt B.; Hillert, Lena; Åkerstedt, Torbjörn; Lowden, Arne; Kuster, Niels; Ebert, Sven; Boutry, Clementine; Moffat, Scott D.; Berg, Mats; Wiholm, Clairy. Effects from 884 MHz mobile phone radiofrequency on brain electrophysiology, sleep, cognition, and well-being, Referierte Publikationen, Chicago, 2008.

- Janssen, D. (22 January 2016). "Smartphone-induced sleep deprivation and its implications for public health". Europeanpublichealth.com. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Evli, Mahmut; Şimşek, Nuray; Işıkgöz, Mahmut; Öztürk, Halil İbrahim (2022). "Internet addiction, insomnia, and violence tendency in adolescents". International Journal of Social Psychiatry: 002076402210909. doi:10.1177/00207640221090964. ISSN 0020-7640. PMID 35470724. S2CID 248390830.

- Dhungel A, Zmirou-Navier D, van Deventer E (2015). "Risk management policies and practices regarding radio frequency electromagnetic fields: results from a WHO survey". Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 164 (1–2): 22–27. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncu324. PMC 4401037. PMID 25394650.

- Pierre Le Hir (2015). "Une loi pour encadrer l'exposition aux ondes". Le Monde (in French). No. 29 January 2015.

- Leung, L. and Liang, J., 2015. Mobile Phone Addiction. In Encyclopedia of Mobile Phone Behavior (pp. 640-647). IGI Global

- "Smartphone overuse may 'damage' eyes, say opticians - BBC Newsbeat". BBC Newsbeat. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Bianchi, Adriana; Phillips, James G. (2005). "Psychological Predictors of Problem Mobile Phone Use". Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 8 (1): 39–51. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.563.385. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39. PMID 15738692.

- Osborne, Charlie. "Cyberbullying increases in line with mobile phone usage? (infographic)". ZDNet. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Twenge, Jean (3 August 2017). "Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?". The Atlantic.

- Twenge, Jean M.; Joiner, Thomas E.; Rogers, Megan L.; Martin, Gabrielle N. (14 November 2017). "Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents After 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time". Clinical Psychological Science. 6 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/2167702617723376. S2CID 148724233.

- Brody, Jane E. (9 January 2017). "Hooked on Our Smartphones". The New York Times.

- Turk, Victoria (11 January 2018). "Apple investors say iPhones cause teen depression. Science doesn't". Wired UK.

- Hampton, William; Wilmer, Henry; Olson, Ingrid (2019). "Wired to be connected? Links between mobile technology engagement, intertemporal preference and frontostriatal white matter connectivity". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 14 (4): 367–379. doi:10.1093/scan/nsz024. PMC 6523422. PMID 31086992.

- Hadar, A; Hadas, I; Lazarovits, A (2017). "Answering the missed call: initial exploration of cognitive and electrophysiological changes associated with smartphone use and abuse". PLOS ONE. 12 (7): e0180094. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1280094H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180094. PMC 5497985. PMID 28678870.

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, Oscar; Sonali, Nandavar; Newton, James David Albert; Demant, Daniel; Phillips, James G (12 March 2019). "Problematic Use of Mobile Phones in Australia…Is It Getting Worse?". Front. Psychiatry. 10: 105. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00105. PMC 6422909. PMID 30914975.

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O; King, M; Haque, MM; Washington, S (2017). "Risk factors of mobile phone use while driving in Queensland: Prevalence, attitudes, crash risk perception, and task-management strategies". PLOS ONE. 12 (9): e0183361. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1283361O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183361. PMC 5587103. PMID 28877200.

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, Oscar; Haque, Md. Mazharul; King, Mark; Washington, Simon (October 2018). "Should I Text or Call Here? A Situation-Based Analysis of Drivers' Perceived Likelihood of Engaging in Mobile Phone Multitasking". Risk Analysis. 38 (10): 2144–2160. doi:10.1111/risa.13119. PMID 29813176. S2CID 44146164.

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, Oscar; Haque, Md. Mazharul; King, Mark; Washington, Simon (November 2016). "Understanding the impacts of mobile phone distraction on driving performance: A systematic review" (PDF). Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 72: 360–380. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2016.10.006.

- "The Dangers of Distracted Driving". Federal Communications Commission. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Cell Phone Distracted Driving". National Safety Council.

- Cultivate. "Mobile Phone Laws In The UK - Make Sure You're Up To Date". IMS Law. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Samaha, Maya; Hawi, Nazir S. (2016). "Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life". Computers in Human Behavior. 57: 321–325. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045.

- Bian, Mengwei; Leung, Louis (8 April 2014). "Linking Loneliness, Shyness, Smartphone Addiction Symptoms, and Patterns of Smartphone Use to Social Capital". Social Science Computer Review. 33 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1177/0894439314528779. S2CID 16554067.

- Lin, Yu-Hsuan; Lin, Yu-Cheng; Lee, Yang-Han; Lin, Po-Hsien; Lin, Sheng-Hsuan; Chang, Li-Ren; Tseng, Hsien-Wei; Yen, Liang-Yu; Yang, Cheryl C.H. (2015). "Time distortion associated with smartphone addiction: Identifying smartphone addiction via a mobile application (App)". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 65: 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.003. PMID 25935253.

- Demirci, Kadir; Akgönül, Mehmet; Akpinar, Abdullah (2015). "Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students". Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 4 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.010. PMC 4500888. PMID 26132913.

- Kim, Hyunna (31 December 2013). "Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction". Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 9 (6): 500–505. doi:10.12965/jer.130080. PMC 3884868. PMID 24409425.

- Young, Kimberly S. (2007). "Cognitive Behavior Therapy with Internet Addicts: Treatment Outcomes and Implications". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 10 (5): 671–679. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.9971. PMID 17927535. S2CID 13951774.

- Young, Kimberly S.; Yue, Xiao Dong; Ying, Li (9 October 2012), "Prevalence Estimates and Etiologic Models of Internet Addiction", Internet Addiction, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–17, doi:10.1002/9781118013991.ch1, ISBN 9781118013991

- Liu, Chun-Hao; Lin, Sheng-Hsuan; Pan, Yuan-Chien; Lin, Yu-Hsuan (2016). "Smartphone gaming and frequent use pattern associated with smartphone addiction". Medicine. 95 (28): e4068. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004068. PMC 4956785. PMID 27428191.

- "WHO guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age" (PDF). World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Hern, Alex (20 June 2017). "Will turning your phone to greyscale really do wonders for your attention?". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Baumer, Eric P.S.; Ames, Morgan G.; Brubaker, Jed R.; Burrell, Jenna; Dourish, Paul (2014). "Refusing, limiting, departing". Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI EA '14. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press: 65–68. doi:10.1145/2559206.2559224. ISBN 9781450324748. S2CID 19808650.

- ZDF. "Einfach mal abschalten -Suchtfaktor Smartphone" (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "iOS 12: Getting to know Screen Time and stronger parental controls". CNET. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Hiniker, Alexis; Hong, Sungsoo (Ray); Kohno, Tadayoshi; Kientz, Julie A. (2016). "MyTime". Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '16. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press: 4746–4757. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858403. ISBN 9781450333627. S2CID 2928701.

- Löchtefeld, Markus; Böhmer, Matthias; Ganev, Lyubomir (2013). "AppDetox". Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia - MUM '13. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press: 1–2. doi:10.1145/2541831.2541870. ISBN 9781450326483. S2CID 3338918.

- Ruan, Wenjie; Sheng, Quan Z.; Yao, Lina; Tran, Nguyen Khoi; Yang, Yu Chieh (2016). "PreventDark: Automatically detecting and preventing problematic use of smartphones in darkness". 2016 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communication Workshops (PerCom Workshops). IEEE: 1–3. doi:10.1109/percomw.2016.7457071. ISBN 9781509019410. S2CID 18999633.

- Okeke, Fabian; Sobolev, Michael; Dell, Nicola; Estrin, Deborah (2018). "Good vibrations". Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services - MobileHCI '18. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press: 1–12. doi:10.1145/3229434.3229463. ISBN 9781450358989. S2CID 52098664.

- Ko, Minsam; Chung, Kyong-Mee; Yang, Subin; Lee, Joonwon; Heizmann, Christian; Jeong, Jinyoung; Lee, Uichin; Shin, Daehee; Yatani, Koji (2015). "NUGU". Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing - CSCW '15. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press: 1235–1245. doi:10.1145/2675133.2675244. ISBN 9781450329224. S2CID 15281296.

- Jones, Allison (12 March 2019). "Ontario to ban cellphones in classrooms next school year". The Canadian Press. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Smith, Rory (31 July 2018). "France bans smartphones from schools". CNN. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Melinda, Smith; Robinson, Lawrence; Segal, Jeanne (October 2019). "Smartphone Addiction". HelpGuide. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Signs and Symptoms of Cell Phone Addiction". PsychGuides.com. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Sela A., Rozenboim N., Chalutz Ben-Gal, Hila (2022). "Smartphone use behavior and quality of life: What is the role of awareness?" (PDF). PLoS ONE 17(3).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hong, Fu-Yuan; Chiu, Shao-I.; Huang, Der-Hsiang (November 2012). "A model of the relationship between psychological characteristics, mobile phone addiction and use of mobile phones by Taiwanese university female students". Computers in Human Behavior. 28 (6): 2152–2159. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.020. ISSN 0747-5632.

- VanTeijlingen, Edwin R; Sathian, Brijesh (23 April 2018). "Addiction of smart phone and its health implications". Journal of Biomedical Sciences. 3 (3): 31–32. doi:10.3126/jbs.v3i3.19671. ISSN 2382-5545.

- Herrero, Juan; Urueña, Alberto; Torres, Andrea; Hidalgo, Antonio (1 February 2019). "Socially Connected but Still Isolated: Smartphone Addiction Decreases Social Support Over Time". Social Science Computer Review. 37 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1177/0894439317742611. ISSN 0894-4393. S2CID 64619582.

Further reading

- Roberts, James A. (2015). TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING: Are You Addicted to Your Smartphone?. Sentia Publishing. ISBN 978-0996300476.

- Richtel, Matt (22 April 2007). "It Don't Mean a Thing if You Ain't Got That Ping". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Takao, Motoharu; Takahashi, Susumu; Kitamura, Masayoshi (October 2009). "Addictive Personality and Problematic Mobile Phone Use". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 12 (5): 501–507. doi:10.1089/cpb.2009.0022. PMID 19817562. S2CID 2777826.

- Sánchez-Martínez, Mercedes; Otero, Angel (April 2009). "Factors Associated with Cell Phone Use in Adolescents in the Community of Madrid (Spain)". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 12 (2): 131–137. doi:10.1089/cpb.2008.0164. PMID 19072078. S2CID 11934182.

- Griffiths, Mark (April 2000). "Does Internet and Computer 'Addiction' Exist? Some Case Study Evidence" (PDF). CyberPsychology & Behavior. 3 (2): 211–218. doi:10.1089/109493100316067.

- Krajewska-Kulak, E., et al. Problematic mobile phone using among the Polish and Belarusian University students, a comparative study. Progress in Health Sciences 2.1 (2012): 45+. Academic OneFile database. 4 December 2012.

- Gil Brand, Making Smart Use of the Smartphone, 14 February 2017.

External links

Media related to People with mobile telephones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to People with mobile telephones at Wikimedia Commons