Schizencephaly

Schizencephaly (from Greek skhizein 'to split', and enkephalos 'brain')[1][2] is a rare birth defect characterized by abnormal clefts lined with grey matter that form the ependyma of the cerebral ventricles to the pia mater. These clefts can occur bilaterally or unilaterally. Common clinical features of this malformation include epilepsy, motor deficits, and psychomotor retardation.[3]

| Schizencephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

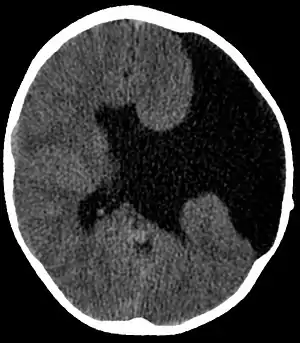

| Axial CT scan showing schizencephaly in a 6-year-old child | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, neurology |

Presentation

Schizencephaly can be distinguished from porencephaly by the fact that in schizencephaly, the fluid-filled component is entirely lined by heterotopic grey matter, while a porencephalic cyst is lined mostly by white matter. Individuals with clefts in both hemispheres, or bilateral clefts, are often developmentally delayed and have delayed speech and language skills and corticospinal dysfunction. Individuals with smaller, unilateral clefts (clefts in one hemisphere) may be weak or paralyzed on one side of the body and may have average or near-average intelligence. Patients with schizencephaly may also have varying degrees of microcephaly, Cognitive impairment, hemiparesis (weakness or paralysis affecting one side of the body), or quadriparesis (weakness or paralysis affecting all four extremities), and may have reduced muscle tone (hypotonia). Most patients have seizures, and some may have hydrocephalus.[4]

Causes

In schizencephaly, the neurons border the edge of the cleft, implying a very early disruption of the usual grey matter migration during embryogenesis. The cause of the disruption is not known, but likely the cause may be either genetic or a physical insult, such as infection, infarction, hemorrhage, in utero stroke, exposure to a toxin, or mutation. It is thought that normal neuron migration during the second trimester of intrauterine development, when primitive neuron precursors (germinal matrix) migrate from just beneath the ventricular ependyma to the peripheral hemispheres where they form the cortical grey matter.

Genetic

There was once thought to be a genetic association with the EMX2 gene, although this theory has recently lost support.[5] However it has been confirmed that mutations in the COL4A1 gene occur in some patients with schizencephaly.[6][7]

In utero infections

Schizencephaly may also be caused by environmental toxin exposure during pregnancy, infection during pregnancy (such as Cytomegalovirus), or a vascular insult. Often there are additional associated heterotopias (isolated islands of neurons) which indicate a failure of migration of the neurons to their final position in the brain caused by possible stroke.

Diagnosis

- Radiological methods like computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - unilateral or bilateral clefting of the brain.

- Genetic testing for confirmation of mutations in the genes associated with susceptibility to the condition.

Treatment

Treatment for individuals with schizencephaly generally consists of physical therapy (KG-ZNS with Vojta Methode), occupational therapy (with specific emphasis on neuro-developmental therapy techniques), treatment for seizures,[4] and, in cases that are complicated by hydrocephalus, a shunt.

Prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with schizencephaly varies depending on the size of the clefts and the degree of neurological deficit.[4]

Frequency

In some cases, the defect is linked to mutations of the EMX2, SIX3, and Collagen, type IV, alpha 1 genes. Because having a sibling with schizencephaly has been statistically shown to increase risk of the disorder, it is possible that there is a heritable genetic component to the disease.[8]

References

- "schizo–". The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.).

- "encephalic". The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.).

- "Schizencephaly". Orphanet. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "NINDS Schizencephaly Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NIH. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- Tietjen, Ian; Bodell, Adria; Apse, Kira; Mendonza, Ashley M.; Chang, Bernard S.; Shaw, Gary M.; Barkovich, A. James; Lammer, Edward J.; Walsh, Christopher A. (15 June 2007). "Comprehensive EMX2 genotyping of a large schizencephaly case series". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 143A (12): 1313–1316. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31767. PMID 17506092. S2CID 34724677.

- Yoneda, Yuriko; Haginoya, Kazuhiro; Kato, Mitsuhiro; Osaka, Hitoshi; Yokochi, Kenji; Arai, Hiroshi; Kakita, Akiyoshi; Yamamoto, Takamichi; Otsuki, Yoshiro; Shimizu, Shin-ichi; Wada, Takahito; Koyama, Norihisa; Mino, Yoichi; Kondo, Noriko; Takahashi, Satoru; Hirabayashi, Shinichi; Takanashi, Jun-ichi; Okumura, Akihisa; Kumagai, Toshiyuki; Hirai, Satori; Nabetani, Makoto; Saitoh, Shinji; Hattori, Ayako; Yamasaki, Mami; Kumakura, Akira; Sugo, Yoshinobu; Nishiyama, Kiyomi; Miyatake, Satoko; Tsurusaki, Yoshinori; Doi, Hiroshi; Miyake, Noriko; Matsumoto, Naomichi; Saitsu, Hirotomo (January 2013). "Phenotypic Spectrum of Mutations: Porencephaly to Schizencephaly". Annals of Neurology. 73 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1002/ana.23736. PMID 23225343. S2CID 3218598.

- Smigiel, Robert; Cabala, Magdalena; Jakubiak, Aleksandra; Kodera, Hirofumi; Sasiadek, Marek J.; Matsumoto, Naomichi; Sasiadek, Maria M.; Saitsu, Hirotomo (2016-04-01). "Novel COL4A1 mutation in an infant with severe dysmorphic syndrome with schizencephaly, periventricular calcifications, and cataract resembling congenital infection". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 106 (4): 304–307. doi:10.1002/bdra.23488. ISSN 1542-0760. PMID 26879631.

- Skandhan, Avni; Gaillard, Frank. "Schizencephaly". Radiopedia. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

9.^ Herrera Ortiz, A., & Ortiz Sandoval, H. (2021). Open Lip Schizencephaly: A Case Report. Revista Cuarzo, 26(2), 27-29. https://doi.org/10.26752/cuarzo.v26.n2.510