Thymoma

A thymoma is a tumor originating from the epithelial cells of the thymus that is considered a rare malignancy. Thymomas are frequently associated with neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis;[1] thymoma is found in 20% of patients with myasthenia gravis.[2] Once diagnosed, thymomas may be removed surgically. In the rare case of a malignant tumor, chemotherapy may be used.

| Thymoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| An encapsulated thymoma (mixed lymphocytic and epithelial type) | |

| Specialty | Oncology, cardiothoracic surgery |

| Usual onset | Adulthood |

| Treatment | surgical removal, chemotherapy (in malignant cases). |

Signs and symptoms

A third of all people with a thymoma have symptoms caused by compression of the surrounding organs by an expansive mass. These problems may take the form of superior vena cava syndrome, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), cough, or chest pain.[1]

One-third of patients have their tumors discovered because they have an associated autoimmune disorder. As mentioned earlier, the most common of those conditions is myasthenia gravis (MG); 10–15% of patients with MG have a thymoma and, conversely, 30–45% of patients with thymomas have MG. Additional associated autoimmune conditions include thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity, pure red cell aplasia and Good syndrome (thymoma with combined immunodeficiency and hypogammaglobulinemia). Other reported disease associations are with acute pericarditis, agranulocytosis, alopecia areata, ulcerative colitis, Cushing's disease, hemolytic anemia, limbic encephalopathy, myocarditis, nephrotic syndrome, panhypopituitarism, pernicious anemia, polymyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, sensorimotor radiculopathy, stiff person syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and thyroiditis.[1][3]

One-third to one-half of all persons with thymoma have no symptoms at all, and the mass is identified on a chest X-ray or CT/CAT scan performed for an unrelated problem.[1]

Pathology

Thymoma originates from the epithelial cell population in the thymus, and several microscopic subtypes are now recognized.[1] There are three principal histological types of thymoma, depending on the appearance of the cells by microscopy:

- Type A if the epithelial cells have an oval or fusiform shape (less lymphocyte count);

- Type B if they have an epithelioid shape (Type B has three subtypes: B1 (lymphocyte-rich), B2 (cortical) and B3 (epithelial).);[4]

- Type AB if the tumor contains a combination of both cell types.

Thymic cortical epithelial cells have abundant cytoplasm, vesicular nucleus with finely divided chromatin and small nucleoli and cytoplasmic filaments contact adjacent cells. Thymic medullary epithelial cells in contrast are spindle shaped with oval dense nucleus and scant cytoplasm thymoma if recapitulates cortical cell features more, is thought to be less benign.

Diagnosis

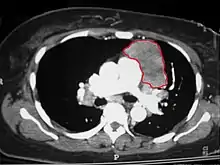

When a thymoma is suspected, a CT/CAT scan is generally performed to estimate the size and extent of the tumor, and the lesion is sampled with a CT-guided needle biopsy. Increased vascular enhancement on CT scans can be indicative of malignancy, as can be pleural deposits.[1] Limited biopsies are associated with a very small risk of pneumomediastinum or mediastinitis and an even-lower risk of damaging the heart or large blood vessels. Sometimes thymoma metastasize for instance to the abdomen.[5]

The diagnosis is made via histologic examination by a pathologist, after obtaining a tissue sample of the mass. Final tumor classification and staging is accomplished pathologically after formal surgical removal of the thymic tumor.

Selected laboratory tests can be used to look for associated problems or possible tumor spread. These include: full blood count, protein electrophoresis, antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor (indicative of myasthenia), electrolytes, liver enzymes and renal function.[1]

Staging

The Masaoka Staging System is used widely and is based on the anatomic extent of disease at the time of surgery:[6]

- I: Completely encapsulated

- IIA: Microscopic invasion through the capsule into surrounding fatty tissue

- IIB: Macroscopic invasion into capsule

- III: Macroscopic invasion into adjacent organs

- IVA: Pleural or pericardial implants

- IVB: Lymphogenous or hematogenous metastasis to distant (extrathoracic) sites

Treatment

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for thymoma. If the tumor is apparently invasive and large, preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be used to decrease the size and improve resectability, before surgery is attempted. When the tumor is an early stage (Masaoka I through IIB), no further therapy is necessary. Removal of the thymus in adults does not appear to induce immune deficiency. In children, however, postoperative immunity may be abnormal and vaccinations for several infectious agents are recommended. Invasive thymomas may require additional treatment with radiotherapy and chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin).[1].[7] Recurrences of thymoma are described in 10-30% of cases up to 10 years after surgical resection, and in the majority of cases also pleural recurrences can be removed. Recently, surgical removal of pleural recurrences can be followed by hyperthermic intrathoracic perfusion chemotherapy or intrathoracic hyperthermic perfused chemotherapy (ITH).

Prognosis

Prognosis is much worse for stage III or IV thymomas as compared with stage I and II tumors. Invasive thymomas uncommonly can also metastasize, generally to pleura, bones, liver or brain in approximately 7% of cases.[1] A study found that slightly over 40% of observed patients with stage III and IV tumors survived for at least 10 years after diagnosis. The median age of these patients at the time of thymoma diagnosis was 57 years. [8]

Patients who have undergone thymectomy for thymoma should be warned of possible severe side effects after yellow fever vaccination. This is probably caused by inadequate T-cell response to live attenuated yellow fever vaccine. Deaths have been reported.

Epidemiology

Men and women are equally affected by thymomas. The typical age at diagnosis is 30–40, although cases have been described in every age group, including children.[1]

Gallery

An encapsulated cystic thymoma.

An encapsulated cystic thymoma. A locally invasive circumscribed thymoma (mixed lymphocytic and epithelial, mixed polygonal and spindle).

A locally invasive circumscribed thymoma (mixed lymphocytic and epithelial, mixed polygonal and spindle)..JPG.webp) Histopathological image of thymoma type B1. Anterior mediastinal mass surgically resected. Hematoxylin & eosin stain.

Histopathological image of thymoma type B1. Anterior mediastinal mass surgically resected. Hematoxylin & eosin stain._CK_CAM5-2.JPG.webp) Histopathological image of thymoma type B1. Anterior mediastinal mass surgically resected. Cytokeratin CAM5.2 immunostain.

Histopathological image of thymoma type B1. Anterior mediastinal mass surgically resected. Cytokeratin CAM5.2 immunostain..JPG.webp) Histopathological image representing a noninvasive thymoma type B1, surgically resected. Hematoxylin & eosin.

Histopathological image representing a noninvasive thymoma type B1, surgically resected. Hematoxylin & eosin. Thymoma. FNA specimen. Field stain.

Thymoma. FNA specimen. Field stain.

See also

References

- Thomas CR, Wright CD, Loehrer PJ (July 1999). "Thymoma: state of the art". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 17 (7): 2280–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2280. PMID 10561285.

- Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins basic pathology. Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Bernard C, Frih H, Pasquet F, Kerever S, Jamilloux Y, Tronc F, Guibert B, Isaac S, Devouassoux M, Chalabreysse L, Broussolle C, Petiot P, Girard N, Sève P (January 2016). "Thymoma associated with autoimmune diseases: 85 cases and literature review". Autoimmunity Reviews. 15 (1): 82–92. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.09.005. PMID 26408958.

- Dadmanesh F, Sekihara T, Rosai J (May 2001). "Histologic typing of thymoma according to the new World Health Organization classification". Chest Surgery Clinics of North America. 11 (2): 407–20. PMID 11413764.

- van Geffen WH, Sietsma J, Roelofs PM, Hiltermann TJ (December 2011). "A malignant retroperitoneal mass--a rare presentation of recurrent thymoma". BMJ Case Reports. 2011: bcr0920114737. doi:10.1136/bcr.09.2011.4737. PMC 3229325. PMID 22674945.

- Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, Tanioka T (December 1981). "Follow-up study of thymomas with special reference to their clinical stages". Cancer. 48 (11): 2485–92. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19811201)48:11<2485::AID-CNCR2820481123>3.0.CO;2-R. PMID 7296496.

- NCCN Thymoma, Guidelines (2016). "NCCN Thymoma Guidelines" (PDF). NCCN Guidelines (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Wilkins KB, Sheikh E, Green R, Patel M, George S, Takano M, Diener-West M, Welsh J, Howard S, Askin F, Bulkley GB (October 1999). "Clinical and pathologic predictors of survival in patients with thymoma". Annals of Surgery. 230 (4): 562–72, discussion 572–4. doi:10.1097/00000658-199910000-00012. PMC 1420905. PMID 10522726.