Belfast

Belfast (/ˈbɛlfæst/ BEL-fast, /-fɑːst/ -fahst[lower-alpha 1]; from Irish: Béal Feirste [bʲeːlˠ ˈfʲɛɾˠ(ə)ʃtʲə], meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford'[4]) is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom[5] and the second-largest in Ireland. It had a population of 345,418 in 2021.[2]

Belfast

| |

|---|---|

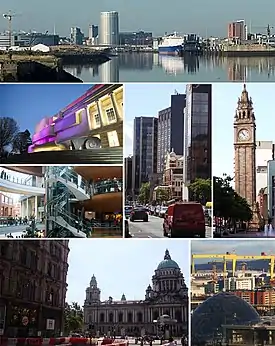

Skyline and buildings throughout the City of Belfast | |

Coat of arms with motto "Pro Tanto Quid Retribuamus" (Latin: "What shall we give in return for so much") | |

Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Area | 51.16[1] sq mi (132.5 km2) |

| Population | City of Belfast: 345,418 (2021)[2] Metropolitan area: 671,559 (2011)[3] |

| Irish grid reference | J338740 |

| District |

|

| County |

|

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BELFAST |

| Postcode district | BT1–BT17, BT29 (part), BT36 (part), BT58 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly |

|

| Website | www.belfastcity.gov.uk |

By the early 19th century, Belfast was a major port. It played an important role in the Industrial Revolution in Ireland, becoming briefly the biggest linen-producer in the world, earning it the nickname "Linenopolis".[6] By the time it was granted city status in 1888, it was a major centre of Irish linen production, tobacco-processing and rope-making. Shipbuilding was also a key industry; the Harland and Wolff shipyard, which built the RMS Titanic, was the world's largest shipyard.[7] Belfast as of 2019 has a major aerospace and missiles industry. Industrialisation, and the inward migration[8] it brought, made Belfast Northern Ireland's biggest city. Following the partition of Ireland in 1921, Belfast became the seat of government for Northern Ireland. Belfast's status as a global industrial centre ended in the decades after the Second World War. Belfast suffered greatly during the violence that accompanied the partition of Ireland, and especially during the more recent conflict known as the Troubles.

Belfast is still a port with commercial and industrial docks, including the Harland and Wolff shipyard, dominating the Belfast Lough shoreline. It is served by two airports: George Best Belfast City Airport, 3 miles (5 kilometres) from the city centre, and Belfast International Airport 15 miles (24 kilometres) west of the city. The Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC) listed Belfast as a Gamma + global city in 2020.[9]

Name

The name Belfast derives from the Irish Béal Feirsde, later spelt Béal Feirste (Irish pronunciation: [bʲeːlˠ ˈfʲɛɾˠ(ə)ʃtʲə])[10] The word béal means "mouth" or "river-mouth" while feirsde/feirste is the genitive singular of fearsaid and refers to a sandbar or tidal ford across a river's mouth.[10][11] The name therefore translates literally as "(river) mouth of the sandbar" or "(river) mouth of the ford".[10] The sandbar formed at the confluence (at present-day Donegall Quay) of two rivers: the Lagan, which flows into Belfast Lough, and the Lagan's tributary the Farset ("mouth of the Farset" might be an alternative interpretation)[12][13] This area became the hub around which the original settlement developed.[14]

The compilers of Ulster-Scots use various transcriptions of local pronunciations of "Belfast" (with which they sometimes are also content)[15][16] including Bilfawst,[17][18] Bilfaust[19] or Baelfawst.[20]

History

The county borough of Belfast was created when it was granted city status by Queen Victoria in 1888,[21] and the city continues to straddle County Antrim on the left bank of the Lagan and County Down on the right.[22]

Origins

The site of Belfast has been occupied since the Bronze Age. The Giant's Ring, a 5,000-year-old henge, is located near the city,[23] and the remains of Iron Age hill forts can still be seen in the surrounding hills. Belfast remained a small settlement of little importance during the Middle Ages. The Normans may have built a castle on a site now bounded by Donegall Place, Castle Place, Cornmarket and Castle Lane in the late twelfth century or early thirteenth century, right in the centre of what is now Belfast City Centre.[24] However, this original 'Belfast Castle' was much smaller and of far less strategic importance than nearby Carrickfergus Castle, which was constructed at Carrickfergus and was probably built in the late 1170s.

As lords of Clandeboye, the O'Neill dynasty were the local Irish power.[24] In 1616, after the Nine Years' War, the last of the local line, Conn O'Neill (remembered in Connswater River),[25] was forced to sell their remaining stronghold, the Grey Castle or Castle Reagh (An Caisleán Riabhach in Irish)[26] in the hills to the east of Belfast, together with surrounding lands, to English and Scottish adventurers.

The early town

.png.webp)

Belfast was established as a town in 1613 by Sir Arthur Chichester.[27] Chichester also had Belfast Castle rebuilt at this time.[24] The mainly English and Manx settlers took Anglican communion at Corporation Church on the quay-side end of High Street. But it was with Scottish Presbyterians that the town was to grow as an industrial port. Together with French Huguenot refugees, they introduced the production of linen, an industry that carried Belfast trade to the Americas.[28]

Reluctant to let valuable crop go to seed, flax growers and linen merchants benefited from a three-way exchange. Fortunes were made carrying rough linen clothing and salted provisions to the slave plantations of the West Indies; sugar and rum to Baltimore and New York; and for the return to Belfast of flaxseed from the colonies where the relative scarcity of labour made unprofitable the processing of the flax into linen fibre.[29] Profits from the trade financed improvements in the town's commercial infrastructure, including the Lagan Canal, new docks and quays, and the construction of the White Linen Hall which together attracted to Belfast the linen trade that had formerly gone through Dublin. Public outrage, however, defeated the proposal of the greatest of the merchant houses, Cunningham and Greg, to commission ships for the Middle Passage.[30]

As "Dissenters" from the established Church, Presbyterians were conscious of sharing, if only in part, the disabilities of Ireland's dispossessed Roman Catholic majority; and of being denied representation in the Irish Parliament. Belfast's two MPs remained nominees of the Chichesters (Marquesses of Donegall).[31][32] With their American kinsmen, the region's Presbyterians were to share a growing disaffection from the Crown.

When early in the American War of Independence, Belfast Lough was raided by the privateer John Paul Jones, the townspeople assembled their own Volunteer militia. Formed ostensibly for defence of the Kingdom, the Volunteers were soon pressing their own protest against "taxation without representation". Further emboldened by the French Revolution, a more radical element in the town, the United Irishmen, called for Catholic emancipation and an independent representative government for the country.[33] In hopes of French assistance, in 1798 the Society organised a republican insurrection. The rebel tradesmen and tenant farmers were defeated north of the town at the Battle of Antrim and to the south at the Battle of Ballynahinch.

Among surviving elements of the early pre-Victorian town are the Belfast Entries, 17th-century alleyways off High Street, including, in Winecellar's Entry, White's Tavern (rebuilt 1790); the First Presbyterian (Non-Subscribing) Church (1781–83) in Rosemary Street (whose members led the abolitionist charge against Greg and Cunningham);[34] St George's Church of Ireland (1816) on the High Street site of the old Corporation Church; and the oldest public building in Belfast, Clifden House (1771–74), the Belfast Charitable Society poorhouse on North Queen Street.[35]

The industrial city

.jpg.webp)

Rapid industrial growth in the nineteenth century drew in landless Catholics from outlying rural and western districts, most settling to the west of the town. The plentiful supply of cheap labour helped attract English and Scottish capital to Belfast, but it was also a cause of insecurity. Protestant workers who organised to secure their access to jobs and housing gave a new lease of life in the town to the once largely rural Orange Order. Sectarian tensions were heightened by movements to repeal the Acts of Union (which followed the 1798 rebellion) and to restore a Parliament in Dublin. Given the progressive enlargement of the British electoral franchise, this would have had an overwhelming Catholic majority and, it was widely believed, interests inimical to the Protestant and industrial north. In 1864 and 1886 the issue had helped trigger deadly sectarian riots.

Sectarian tension was not in itself unique to Belfast: it was shared with Liverpool and Glasgow, cities that following the Great Famine had also experienced large-scale Irish Catholic immigration.[36] But also common to this "industrial triangle" were traditions of labour militancy. In 1919, workers in all three cities struck for a ten-hour reduction in the working week. In Belfast—notwithstanding the political friction caused by Sinn Féin's electoral triumph in the south—this involved some 60,000 workers, Protestant and Catholic, in a four-week walk-out.[37]

In a demonstration of their resolve not to submit to a Dublin parliament, in 1912 Belfast City Hall unionists presented the Ulster Covenant, which, with an associated Declaration for women, was to accumulate over 470,000 signatures. This was followed by the drilling and eventual arming of a 100,000-strong Ulster Volunteer Force. The crisis was abated by the onset of the Great War, the sacrifices of the UVF in which continue to be commemorated in the city (Somme Day) by unionist and loyalist organisations.

In 1921, as the greater part of Ireland seceded as the Irish Free State, Belfast became the capital of the six counties remaining as Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom. In 1932, the devolved parliament for the region was housed in new buildings at Stormont on the eastern edge of the city. In 1920–21, as the island of Ireland was partitioned, up to 500 people were killed in disturbances in Belfast, the bloodiest period of strife in the city until the Troubles of the late 1960s onwards.[38] This period of communal violence (1920–22) was commonly referred to as the Belfast Pogrom.

The Blitz and post-war redevelopment

Belfast was heavily bombed during World War II. Initial raids were a surprise as the city was believed to be outside of the range of German bomber planes. In one raid, in 1941, German bombers killed around one thousand people and left tens of thousands homeless. Apart from London, this was the greatest loss of life in a night raid during the Blitz.[39]

In the spring of 1942, the German Luftwaffe appeared twice over Belfast. In addition to the shipyards and the Shorts Brothers aircraft factory, the Belfast Blitz severely damaged or destroyed more than half the city's housing stock, devastated the old town centre around High Street, and killed over a thousand people.[40]

At the end of World War II, the Unionist Government undertook programmes of "slum clearance" (the Blitz had exposed the "uninhabitable" condition of much of the city's housing) which involved decanting populations out of mill and factory, and constructing terraced streets into new peripheral housing estates.[41] Road construction schemes, including the terminus of the M1 and the Westlink severed the streets linking north and west Belfast to the city centre, for example the dockland community of Sailortown.[42]

The cost was borne by the British Exchequer. In what the Unionist government understood as its reward for wartime service, London had agreed that parity in taxation between Northern Ireland and Great Britain should be matched by parity in the services delivered.[43] In addition to the public construction, this provided for universal health care, comprehensive social security, and "revolutionised access" to secondary and further education.[44] The new welfare state contributed, in turn, to rising expectations; in the 1960s, a possible factor in new and growing protest over the Unionist government's record on civil and political rights.[45]

The Troubles

Belfast has been the scene of various episodes of sectarian conflict between its Catholic and Protestant populations.[46] These opposing groups in this conflict are now often termed republican and loyalist respectively, although they are also loosely referred to as 'nationalist' and 'unionist'. The most recent example of this conflict was known as the Troubles – a civil conflict that raged from the late 1960s to 1998.[47]

Belfast saw some of the worst of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, particularly in the 1970s, with rival paramilitary groups formed on both sides. Bombing, assassination and street violence formed a backdrop to life throughout the Troubles. In December 1971, 15 people, including two children, were killed when the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) bombed McGurk's Bar, the greatest loss of life in a single incident in Belfast.[48][49] Loyalist paramilitaries including the UVF and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) said that the killings they carried out were in retaliation for the IRA campaign. Most of their victims were Catholics with no links to the Provisional IRA.[50] A particularly notorious group, based on the Shankill Road in the mid-1970s, became known as the Shankill Butchers.[51] The Provisional IRA detonated 22 bombs within the confines of Belfast city centre on 21 July 1972, on what is known as Bloody Friday, killing nine people.[52] The British Army, first deployed on the streets in August 1969, was also responsible for civilian deaths. In the deadliest event, known as the Ballymurphy massacre, between 9 and 11 August 1971 members of the Parachute Regiment killed at least nine civilians. A 2021 coroner's report found that all those killed had been innocent and that the killings were "without justification".[53]

During the 1970s and 1980s Belfast was one of the world's most dangerous cities.[54] In all, over 1,600 people were killed in political violence in the city between 1969 and 2001.[55]

During the Troubles the Europa Hotel suffered 36 bomb attacks becoming known as "the most bombed hotel in the world".[56]

Peace lines

An enduring physical legacy of the conflict are the extensive "peace lines" (or "peace walls") that continue to separate loyalist from republican districts. Ranging in length from a few hundred metres to over 5 kilometres, the security barriers have increased both in number and in height and number since 1998.[57][58] They divide communities that account for 14 of the 20 most deprived wards in Northern Ireland.[59] In May 2013, the Northern Ireland Executive committed to the removal of all peace lines by mutual consent.[60][61] As the target date of 2023 approaches, only a small number have been dismantled.[62]

Governance

Belfast was granted borough status by James VI and I in 1613 and official city status by Queen Victoria in 1888.[63] Since 1973 it has been a local government district under local administration by Belfast City Council.[64] Belfast is represented in both the British House of Commons and in the Northern Ireland Assembly. For elections to the European Parliament, Belfast was within the Northern Ireland constituency.

Local government

Belfast City Council is the local council with responsibility for the city. The city's elected officials are the Lord Mayor of Belfast, Deputy Lord Mayor and High Sheriff who are elected from among 60 councillors. The first Lord Mayor of Belfast was Daniel Dixon, who was elected in 1892.[65] The current Lord Mayor is Tina Black of Sinn Féin, while the Deputy Lord Mayor is Michelle Kelly of the Alliance Party.[66] The Lord Mayor's duties include presiding over meetings of the council, receiving distinguished visitors to the city, representing and promoting the city on the national and international stage.[65]

In 1997, unionists lost overall control of Belfast City Council for the first time in its history, with the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland gaining the balance of power between nationalists and unionists. This position was confirmed in five subsequent council elections, with mayors from Sinn Féin and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), both of whom are nationalist parties, and the cross-community Alliance Party regularly elected since. The first nationalist Lord Mayor of Belfast was Alban Maginness of the SDLP, in 1997.

Northern Ireland Assembly and Westminster

.jpg.webp)

As Northern Ireland's capital city, Belfast is host to the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont, the site of the devolved legislature for Northern Ireland. Belfast is divided into four Northern Ireland Assembly and UK parliamentary constituencies: Belfast North, Belfast West, Belfast South and Belfast East. All four extend beyond the city boundaries to include parts of Castlereagh, Lisburn and Newtownabbey districts. In the Northern Ireland Assembly Elections in 2022, Belfast elected 20 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), 5 from each constituency. Belfast elected 7 Sinn Féin, 5 DUP, 5 Alliance Party, 1 SDLP, 1 UUP and 1 PBPA MLAs.[67] In the 2017 UK general election, Belfast elected one Member of Parliament (MP) from each constituency to the House of Commons at Westminster, London. This comprised 3 DUP and 1 Sinn Féin. In the 2019 UK general election, the DUP lost two of their seats in Belfast; to Sinn Féin in North Belfast and to the SDLP in South Belfast.

Geography

Belfast is at the western end of Belfast Lough and at the mouth of the River Lagan giving it the ideal location for the shipbuilding industry that once made it famous. When the Titanic was built in Belfast in 1911–1912, Harland and Wolff had the largest shipyard in the world.[68] Belfast is situated on Northern Ireland's eastern coast at 54°35′49″N 05°55′45″W. A consequence of this northern latitude is that it both endures short winter days and enjoys long summer evenings. During the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, local sunset is before 16:00 while sunrise is around 08:45. This is balanced by the summer solstice in June, when the sun sets after 22:00 and rises before 05:00.[69]

In 1994, a weir was built across the river by the Laganside Corporation to raise the average water level so that it would cover the unseemly mud flats which gave Belfast its name[70] (from Irish Béal Feirste 'The sandy ford at the river mouth').[11] The area of Belfast Local Government District is 42.31 square miles (109.6 km2).[71]

The River Farset is also named after this silt deposit (from the Irish feirste meaning "sand spit"). Originally a more significant river than it is today, the Farset formed a dock on High Street until the mid 19th century. Bank Street in the city centre referred to the river bank and Bridge Street was named for the site of an early Farset bridge.[72] Superseded by the River Lagan as the more important river in the city, the Farset now languishes in obscurity, under High Street. There are no less than twelve other minor rivers in and around Belfast, namely the Blackstaff, the Colin, the Connswater, the Cregagh, the Derriaghy, the Forth, the Knock, the Legoniel, the Loop, the Milewater, the Purdysburn and the Ravernet.[73]

The city is flanked on the north and northwest by a series of hills, including Divis Mountain, Black Mountain and Cavehill, thought to be the inspiration for Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. When Swift was living at Lilliput Cottage near the bottom of Belfast's Limestone Road, he imagined that the Cavehill resembled the shape of a sleeping giant safeguarding the city.[74] The shape of the giant's nose, known locally as Napoleon's Nose, is officially called McArt's Fort probably named after Art O'Neill, a 17th-century chieftain who controlled the area at that time.[75] The Castlereagh Hills overlook the city on the southeast.

Climate

As with the vast majority of the rest of Ireland, Belfast has a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification), with a narrow range of temperatures and rainfall throughout the year. The climate of Belfast is significantly milder than most other locations in the world at a similar latitude, due to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream. There are currently five weather observing stations in the Belfast area: Helen's Bay, Stormont, Newforge, Castlereagh, and Ravenhill Road. Slightly further afield is Aldergrove Airport.[76] The highest temperature recorded at any official weather station in the Belfast area was 30.8 °C (87.4 °F) at Shaw's Bridge on 12 July 1983.[77]

The city gets significant precipitation (greater than 1 mm) on 157 days in an average year with an average annual rainfall of 846 millimetres (33.3 in),[78] less than areas of northern England or most of Scotland,[77] but higher than Dublin or the south-east coast of Ireland.[79] As an urban and coastal area, Belfast typically gets snow on fewer than 10 days per year.[77] The absolute maximum temperature at the weather station at Stormont is 29.7 °C (85.5 °F), set during July 1983.[80] In an average year the warmest day will rise to a temperature of 25.0 °C (77.0 °F)[81] with a day of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above occurring roughly once every two in three years.[82] The absolute minimum temperature at Stormont is −9.9 °C (14 °F), during January 1982,[83] although in an average year the coldest night will fall no lower than −4.5 °C (23.9 °F) with air frost being recorded on just 26 nights.[84] The lowest temperature to occur in recent years was −8.8 °C (16.2 °F) on 22 December 2010.[85]

The nearest weather station for which sunshine data and longer term observations are available is Belfast International Airport (Aldergrove). Temperature extremes here have slightly more variability due to the more inland location. The average warmest day at Aldergrove for example will reach a temperature of 25.4 °C (77.7 °F),[86] (1.0 °C [1.8 °F] higher than Stormont) and 2.1 days[87] should attain a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above in total. Conversely the coldest night of the year averages −6.9 °C (19.6 °F)[88] (or 1.9 °C [3.4 °F] lower than Stormont) and 39 nights should register an air frost.[89] Some 13 more frosty nights than Stormont. The minimum temperature at Aldergrove was −14.9 °C (5.2 °F), during December 2010.

| Climate data for Belfast (Stormont Castle),[lower-alpha 2] elevation: 56 m (184 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1960–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.9 (14.2) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92.5 (3.64) |

71.6 (2.82) |

73.9 (2.91) |

64.4 (2.54) |

67.7 (2.67) |

74.4 (2.93) |

77.0 (3.03) |

86.0 (3.39) |

74.6 (2.94) |

97.2 (3.83) |

102.5 (4.04) |

95.2 (3.75) |

976.9 (38.46) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 15.3 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 11.5 | 13.3 | 15.4 | 14.5 | 157.8 |

| Source: KNMI[90][91][92] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Belfast (Newforge),[lower-alpha 3] elevation: 40 m (131 ft), 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 88.5 (3.48) |

70.3 (2.77) |

71.4 (2.81) |

60.4 (2.38) |

59.6 (2.35) |

69.0 (2.72) |

73.6 (2.90) |

85.0 (3.35) |

69.6 (2.74) |

95.8 (3.77) |

102.3 (4.03) |

93.3 (3.67) |

938.7 (36.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.4 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 11.6 | 13.8 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 156.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40.1 | 65.2 | 97.7 | 157.1 | 185.1 | 151.1 | 146.3 | 141.9 | 112.0 | 92.4 | 52.9 | 35.3 | 1,277 |

| Source: Met Office[93] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Belfast International Airport, elevation: 63 m (207 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1958–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.8 (9.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 77.0 (3.03) |

63.3 (2.49) |

60.6 (2.39) |

55.6 (2.19) |

55.9 (2.20) |

68.0 (2.68) |

78.8 (3.10) |

84.5 (3.33) |

69.2 (2.72) |

88.0 (3.46) |

87.7 (3.45) |

83.5 (3.29) |

872.0 (34.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.7 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 14.2 | 12.1 | 14.0 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 161.3 |

| Average snowy days | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 19 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 89 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 92 | 92 | 91 | 90 | 89 | 91 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 48.7 | 72.1 | 108.4 | 157.8 | 197.9 | 167.6 | 152.0 | 146.4 | 121.5 | 91.2 | 61.3 | 47.1 | 1,372 |

| Source 1: Met Office[94] NOAA (relative humidity and snow days 1961–-1990)[95] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[96][97] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Belfast | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 8.8 (47.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Source: seatemperature.org[98] | |||||||||||||

Areas and districts

The townlands of Belfast are its oldest surviving land divisions and most pre-date the city. Belfast expanded very rapidly from being a market town to becoming an industrial city during the course of the 19th century. Because of this, it is less an agglomeration of villages and towns which have expanded into each other, than other comparable cities, such as Manchester or Birmingham. The city expanded to the natural barrier of the hills that surround it, overwhelming other settlements. Consequently, the arterial roads along which this expansion took place (such as the Falls Road or the Newtownards Road) are more significant in defining the districts of the city than nucleated settlements. Parts of Belfast are segregated by walls, commonly known as "peace lines", erected by the British Army after August 1969, and which still divide 14 districts in the inner city.[99] In 2008 a process was proposed for the removal of the 'peace walls'.[100] In June 2007, a £16 million programme was announced which will transform and redevelop streets and public spaces in the city centre.[101] Major arterial roads (quality bus corridor) into the city include the Antrim Road, Shore Road, Holywood Road, Newtownards Road, Castlereagh Road, Cregagh Road, Ormeau Road, Malone Road, Lisburn Road, Falls Road, Springfield Road, Shankill Road, and Crumlin Road, Four Winds.[102]

Belfast city centre is divided into two postcode districts, BT1 for the area lying north of the City Hall, and BT2 for the area to its south. The industrial estate and docklands BT3. The rest of the Belfast post town is divided in a broadly clockwise system from BT3 in the north-east round to BT15, with BT16 and BT17 further out to the east and west respectively. Although BT derives from Belfast, the BT postcode area extends across the whole of Northern Ireland.[103]

Since 2001, boosted by increasing numbers of tourists, the city council has developed a number of cultural quarters. The Cathedral Quarter takes its name from St Anne's Cathedral (Church of Ireland) and has taken on the mantle of the city's key cultural locality.[104] It hosts a yearly visual and performing arts festival.

Custom House Square is one of the city's main outdoor venues for free concerts and street entertainment. The Gaeltacht Quarter is an area around the Falls Road in west Belfast which promotes and encourages the use of the Irish language.[105] The Queen's Quarter in south Belfast is named after Queen's University. The area has a large student population and hosts the annual Belfast International Arts Festival each autumn. It is home to Botanic Gardens and the Ulster Museum, which was reopened in 2009 after major redevelopment.[106] The Golden Mile is the name given to the mile between Belfast City Hall and Queen's University. Taking in Dublin Road, Great Victoria Street, Shaftesbury Square and Bradbury Place, it contains some of the best bars and restaurants in the city.[107] Since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the nearby Lisburn Road has developed into the city's most exclusive shopping strip.[108][109] Finally, the Titanic Quarter covers 0.75 km2 (185 acres) of reclaimed land adjacent to Belfast Harbour, formerly known as Queen's Island. Named after RMS Titanic, which was built here in 1912,[68] work has begun which promises to transform some former shipyard land into "one of the largest waterfront developments in Europe".[110] Plans include apartments, a riverside entertainment district, and a major Titanic-themed museum.[110]

In its 2018 report on Best Places to Live in Britain, The Sunday Times named Ballyhackamore, "the brunch capital of Belfast", as the best place in Northern Ireland.[111][112] The district of Ballyhackamore has even acquired the name "Ballysnackamore" due to the preponderance of dining establishments in the area.[113]

Cityscape

Architecture

The architectural style of Belfast's public buildings range from a small set of Georgian buildings, many examples of Victorian, including the main Lanyon Building at Queen's University Belfast and the Linenhall Library, (both designed by Sir Charles Lanyon). There are also many examples of Edwardian, such as the City Hall, to modern, such as the Waterfront Hall.

The City Hall was finished in 1906 and was built to reflect Belfast's city status, granted by Queen Victoria in 1888. The Edwardian architectural style of Belfast City Hall influenced the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta, India, and Durban City Hall in South Africa.[114][115] The dome is 173 ft (53 m) high and figures above the door state "Hibernia encouraging and promoting the Commerce and Arts of the City".[116]

Among the city's grandest buildings are two former banks: Ulster Bank in Waring Street (built in 1860) and Northern Bank, in nearby Donegall Street (built in 1769). The Royal Courts of Justice in Chichester Street are home to Northern Ireland's Supreme Court. Many of Belfast's oldest buildings are found in the Cathedral Quarter area, which is currently undergoing redevelopment as the city's main cultural and tourist area.[104] Windsor House, 262 ft (80 m) high, has 23 floors and is the second tallest building (as distinct from structure) in Ireland.[117] Work has started on the taller Obel Tower, which already surpasses the height of Windsor House in its unfinished state.

The ornately decorated Crown Liquor Saloon, designed by Joseph Anderson in 1876, in Great Victoria Street is one of only two pubs in the UK that are owned by the National Trust (the other is the George Inn, Southwark in London). It was made internationally famous as the setting for the classic film, Odd Man Out, starring James Mason.[118] The restaurant panels in the Crown Bar were originally made for Britannic, the sister ship of the Titanic,[116] built in Belfast.

The Harland and Wolff shipyard has two of the largest dry docks in Europe,[119] where the giant cranes, Samson and Goliath stand out against Belfast's skyline. Including the Waterfront Hall and the Odyssey Arena, Belfast has several other venues for performing arts. The architecture of the Grand Opera House has an oriental theme and was completed in 1895. It was bombed several times during the Troubles but has now been restored to its former glory.[120] The Lyric Theatre, which re-opened on 1 May 2011 after undergoing a rebuilding programme and is the only full-time producing theatre in Northern Ireland, is where film star Liam Neeson began his career.[121] The Ulster Hall (1859–1862) was originally designed for grand dances but is now used primarily as a concert and sporting venue. Lloyd George, Parnell and Patrick Pearse all attended political rallies there.[116]

A legacy of the Troubles are the many 'peace lines' or 'peace walls' that still act as barriers to reinforce ethno-sectarian residential segregation in the city. In 2017, the Belfast Interface Project published a study entitled 'Interface Barriers, Peacelines & Defensive Architecture' that identified 97 separate walls, barriers and interfaces in Belfast. A history of the development of these structures can be found at the Peacewall Archive.[122]

Parks and gardens

Sitting at the mouth of the River Lagan where it becomes a deep and sheltered lough, Belfast is surrounded by mountains that create a micro-climate conducive to horticulture. From the Victorian Botanic Gardens in the heart of the city to the heights of Cave Hill Country Park, the great expanse of Lagan Valley Regional Park[123] to Colin Glen, Belfast contains an abundance of parkland and forest parks.[124]

Parks and gardens are an integral part of Belfast's heritage, and home to an abundance of local wildlife and popular places for a picnic, a stroll or a jog. Numerous events take place throughout including festivals such as Rose Week and special activities such as bird watching evenings and great beast hunts.[124]

Belfast has over forty public parks. The Forest of Belfast is a partnership between government and local groups, set up in 1992 to manage and conserve the city's parks and open spaces. They have commissioned more than 30 public sculptures since 1993.[125] In 2006, the City Council set aside £8 million to continue this work.[126] The Belfast Naturalists' Field Club was founded in 1863 and is administered by National Museums and Galleries of Northern Ireland.[127]

With an average of 670,000 visitors per year between 2007 and 2011, one of the most popular parks is Botanic Gardens[128] in the Queen's Quarter. Built in the 1830s and designed by Sir Charles Lanyon, Botanic Gardens Palm House is one of the earliest examples of a curvilinear and cast iron glasshouse.[129] Other attractions in the park include the Tropical Ravine, a humid jungle glen built in 1889, rose gardens and public events ranging from live opera broadcasts to pop concerts.[130] U2 played here in 1997. Sir Thomas and Lady Dixon Park, to the south of the city centre, attracts thousands of visitors each year to its International Rose Garden.[131] Rose Week in July each year features over 20,000 blooms.[132] It has an area of 128 acres (0.52 km2) of meadows, woodland and gardens and features a Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Garden, a Japanese garden, a walled garden, and the Golden Crown Fountain commissioned in 2002 as part of the Queen's Golden Jubilee celebrations.[131]

In 2008, Belfast was named a finalist in the Large City (200,001 and over) category of the RHS Britain in Bloom competition along with London Borough of Croydon and Sheffield.

Belfast Zoo is owned by Belfast City Council. The council spends £1.5 million every year on running and promoting the zoo, which is one of the few local government-funded zoos in the UK and Ireland. The zoo is one of the top visitor attractions in Northern Ireland, receiving more than 295,000 visitors a year. The majority of the animals are in danger in their natural habitat. The zoo houses more than 1,200 animals of 140 species including Asian elephants, Barbary lions, Malayan sun bears (one of the few in the United Kingdom), two species of penguin, a family of western lowland gorillas, a troop of common chimpanzees, a pair of red pandas, a pair of Goodfellow's tree-kangaroos and Francois' langurs. The zoo also carries out important conservation work and takes part in European and international breeding programmes which help to ensure the survival of many species under threat.[133]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1757 | 8,549 | — |

| 1782 | 13,105 | +1.72% |

| 1791 | 18,320 | +3.79% |

| 1806 | 22,095 | +1.26% |

| 1821 | 37,277 | +3.55% |

| 1831 | 53,287 | +3.64% |

| 1841 | 75,308 | +3.52% |

| 1851 | 97,784 | +2.65% |

| 1861 | 119,393 | +2.02% |

| 1871 | 174,412 | +3.86% |

| 1881 | 208,122 | +1.78% |

| 1891 | 255,950 | +2.09% |

| 1901 | 349,180 | +3.15% |

| 1911 | 386,947 | +1.03% |

| 1926 | 415,151 | +0.47% |

| 1937 | 438,086 | +0.49% |

| 1951 | 443,671 | +0.09% |

| 1961 | 415,856 | −0.65% |

| 1966 | 398,405 | −0.85% |

| 1971 | 362,082 | −1.89% |

| 1981 | 314,270 | −1.41% |

| 1991 | 279,237 | −1.17% |

| 2001 | 277,391 | −0.07% |

| 2006 | 267,374 | −0.73% |

| 2011 | 286,000 | +1.36% |

| 2014 | 333,000 | +5.20% |

| [134][135][136][137][138][139][140] | ||

At the 2001 census, the population was 276,459,[141] while 579,554 people lived in the wider Belfast Metropolitan Area.[142]

This made it the fifteenth-largest city in the United Kingdom, but the eleventh-largest conurbation.[143]

Belfast experienced a huge growth in population in the first half of the 20th century. This rise slowed and peaked around the start of the Troubles with the 1971 census showing almost 600,000 people in the Belfast Urban Area.[144] Since then, the inner city numbers have dropped dramatically as people have moved to swell the Greater Belfast suburb population. The 2001 census population in the same Urban Area had fallen to 277,391[141] people, with 579,554 people living in the wider Belfast Metropolitan Area.[142]

The 2001 census recorded 81,650 people from Catholic backgrounds and 79,650 people from Protestant backgrounds of working age living in Belfast.[145] The population density in 2011 was 24.88 people/hectare (compared to 1.34 for the rest of Northern Ireland).[146]

As with many cities, Belfast's inner city is currently characterised by the elderly, students and single young people, while families tend to live on the periphery. Socio-economic areas radiate out from the Central Business District, with a pronounced wedge of affluence extending out the Malone Road and Upper Malone Road to the south.[144] An area of deprivation is found in the inner parts of the north and west of the city. The areas around the Falls Road, Ardoyne and New Lodge (Catholic nationalist) and the Shankill Road (Protestant loyalist) are among the ten most deprived wards in Northern Ireland.[147]

Despite a period of relative peace, most areas and districts of Belfast still reflect the divided nature of Northern Ireland as a whole. Many areas are still highly segregated along ethnic, political and religious lines, especially in working-class neighbourhoods.[148]

These zones – Catholic/republican on one side and Protestant/loyalist on the other – are invariably marked by flags, graffiti and murals. Segregation has been present throughout the history of Belfast but has been maintained and increased by each outbreak of violence in the city. This escalation in segregation, described as a "ratchet effect", has shown little sign of decreasing.[149]

The highest levels of segregation in the city are in west Belfast with many areas greater than 90% Catholic. Opposite but comparatively high levels are seen in the predominantly Protestant east Belfast.[150] Areas where segregated working-class areas meet are known as interface areas and sometimes marked by peace lines.[151][152] When violence flares, it tends to be in interface areas.

Ethnic minority communities have been in Belfast since the 1930s.[153] The largest groups are Poles, Chinese and Indians.[154][155]

Since the expansion of the European Union, numbers have been boosted by an influx of Eastern European immigrants. Census figures (2011) showed that Belfast has a total non-white population of 10,219 or 3.3%,[155] while 18,420 or 6.6%[154] of the population were born outside the UK and Ireland.[154] Almost half of those born outside the UK and Ireland live in south Belfast, where they comprise 9.5% of the population.[154] The majority of the estimated 5,000 Muslims[156] and 200 Hindu families[157] living in Northern Ireland live in the Greater Belfast area.

2011 Census

On Census Day (27 March 2011) the usually resident population of Belfast Local Government District was 333,871 accounting for 18.44% of the NI total.[158] This represents a 1.60% increase since the 2001 Census.

On Census Day 27 March 2011, in Belfast Local Government District (2014), considering the resident population:

- 96.77% were white (including Irish Traveller) while 3.23% were from an ethnic minority population;

- 48.82% belong to or were brought up in the Catholic faith and 42.47% belong to or were brought up in a 'Protestant and Other Christian (including Christian related)' denomination; and

- 43.32% indicated that they had a British national identity, 35.10% had an Irish national identity and 26.92% had a Northern Irish national identity.

Respondents could indicate more than one national identity

On Census Day 27 March 2011, in Belfast Local Government District (2014), considering the population aged 3 years old and over:

- 13.45% had some knowledge of Irish;

- 5.23% had some knowledge of Ulster-Scots; and

- 4.34% did not have English as their first language.

On Census Day 27 March 2011, considering the population aged 16 years old and over:

- 25.56% had a degree or higher qualification; while

- 41.21% had no or low (Level 1*) qualifications.

Level 1 is 1–4 O Levels/CSE/GCSE (any grades) or equivalent

On Census Day 27 March 2011, considering the population aged 16 to 74 years old:

- 63.84% were economically active, 36.16% were economically inactive;

- 52.90% were in paid employment; and

- 5.59% were unemployed, of these 43.56% were long-term unemployed.

Long-term unemployed are those who stated that they have not worked since 2009 or earlier

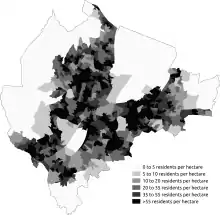

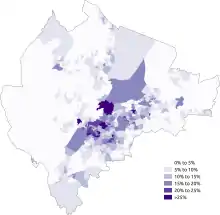

- The Belfast City Council area in the 2011 census

Population density

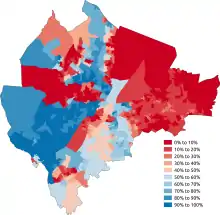

Population density Percentage Catholic or brought up Catholic

Percentage Catholic or brought up Catholic Most commonly stated national identity

Most commonly stated national identity Percentage born outside the UK and Ireland

Percentage born outside the UK and Ireland

Economy

%252C_1907.jpg.webp)

When the population of Belfast town began to grow in the 17th century, its economy was built on commerce.[159] It provided a market for the surrounding countryside and the natural inlet of Belfast Lough gave the city its own port. The port supplied an avenue for trade with Great Britain and later Europe and North America. In the mid-17th century, Belfast exported beef, butter, hides, tallow and corn and it imported coal, cloth, wine, brandy, paper, timber and tobacco.[159]

Around this time, the linen trade in Northern Ireland blossomed and by the middle of the 18th century, one fifth of all the linen exported from Ireland was shipped from Belfast.[159] The present city however is a product of the Industrial Revolution.[160] It was not until industry transformed the linen and shipbuilding trades that the economy and the population boomed. By the turn of the 19th century, Belfast had transformed into the largest linen producing centre in the world,[161] earning the city and its hinterlands the nickname "Linenopolis" during the Victorian Era and into the early part of the 20th century.[162][163]

Belfast harbour was dredged in 1845 to provide deeper berths for larger ships. Donegall Quay was built out into the river as the harbour was developed further and trade flourished.[164] The Harland and Wolff shipbuilding firm was created in 1861, and by the time the Titanic was built, in 1912, it had become the largest shipyard in the world.[68]

Short Brothers plc is a British aerospace company based in Belfast. It was the first aircraft manufacturing company in the world. The company began its association with Belfast in 1936, with Short & Harland Ltd, a venture jointly owned by Shorts and Harland and Wolff. Now known as Shorts Bombardier it works as an international aircraft manufacturer located near the Port of Belfast.[165]

The rise of mass-produced and cotton clothing following World War I were some of the factors which led to the decline of Belfast's international linen trade.[161] Like many British cities dependent on traditional heavy industry, Belfast suffered serious decline since the 1960s, exacerbated greatly in the 1970s and 1980s by the Troubles. More than 100,000 manufacturing jobs have been lost since the 1970s.[166] For several decades, Northern Ireland's fragile economy required significant public support from the British exchequer of up to £4 billion per year.[166]

After the Troubles

The IRA ceasefire in 1994 and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 have given investors increased confidence to invest in Belfast.[167][168] This has led to a period of sustained economic growth and large-scale redevelopment of the city centre. Developments include Victoria Square, the Cathedral Quarter, and the Laganside with the Odyssey complex and the landmark Waterfront Hall.

Other major developments include the regeneration of the Titanic Quarter, and the erection of the Obel Tower, a skyscraper set to be the tallest tower on the island.[169] Today, Belfast is Northern Ireland's educational and commercial hub. In February 2006, Belfast's unemployment rate stood at 4.2%, lower than both the Northern Ireland[170] and the UK average of 5.5%.[171] Over the past 10 years employment has grown by 16.4%, compared with 9.2% for the UK as a whole.[172]

Northern Ireland's peace dividend has led to soaring property prices in the city. In 2007, Belfast saw house prices grow by 50%, the fastest rate of growth in the UK.[173] In March 2007, the average house in Belfast cost £91,819, with the average in south Belfast being £141,000.[174] In 2004, Belfast had the lowest owner occupation rate in Northern Ireland at 54%.[175]

Peace has boosted the numbers of tourists coming to Belfast. There were 6.4 million visitors in 2005, which was a growth of 8.5% from 2004. The visitors spent £285.2 million, supporting more than 15,600 jobs.[176] Visitor numbers rose by 6% to reach 6.8 million in 2006, with tourists spending £324 million, an increase of 15% on 2005.[177] The city's two airports have helped make the city one of the most visited weekend destinations in Europe.[178]

Belfast has been the fastest-growing economy of the thirty largest cities in the UK over the past decade, a new economy report by Howard Spencer has found. "That's because [of] the fundamentals of the UK economy and [because] people actually want to invest in the UK," he commented on that report.[179]

BBC Radio 4's World reported furthermore that despite higher levels of corporation tax in the UK than in the Republic. There are "huge amounts" of foreign investment coming into the country.

The Times wrote about Belfast's growing economy: "According to the region's development agency, throughout the 1990s Northern Ireland had the fastest-growing regional economy in the UK, with GDP increasing 1 per cent per annum faster than the rest of the country. As with any modern economy, the service sector is vital to Northern Ireland's development and is enjoying excellent growth. In particular, the region has a booming tourist industry with record levels of visitors and tourist revenues and has established itself as a significant location for call centres."[180] Since the ending of the region's conflict tourism has boomed in Northern Ireland, greatly aided by low cost.[180]

Der Spiegel, a German weekly magazine for politics and economy, titled Belfast as The New Celtic Tiger which is "open for business".[181]

Infrastructure

Belfast saw the worst of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, with nearly half of the total deaths in the conflict occurring in the city. However, since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, there has been significant urban regeneration in the city centre including Victoria Square, Queen's Island and Laganside as well as the Odyssey complex and the landmark Waterfront Hall. The city is served by two airports: The George Best Belfast City Airport adjacent to Belfast Lough and Belfast International Airport which is near Lough Neagh. Queen's University of Belfast is the main university in the city. The Ulster University also maintains a campus in the city, which concentrates on fine art, design and architecture.

Belfast is one of the constituent cities that makes up the Dublin-Belfast corridor region, which has a population of just under 3 million.

Utilities

Most of Belfast's water is supplied via the Aquarius pipeline from the Silent Valley Reservoir in County Down, created to collect water from the Mourne Mountains.[182] The rest of the city's water is sourced from Lough Neagh, via Dunore Water Treatment Works in County Antrim.[183] The citizens of Belfast pay for their water in their rates bill. Plans to bring in additional water tariffs have been deferred by devolution in May 2007.[184] Belfast has approximately 1,300 km (808 mi) of sewers, which are currently being replaced in a project costing over £100 million and due for completion in 2009.[185]

Power is provided from a number of power stations via NIE Networks Limited transmission lines. Phoenix Natural Gas Ltd. started supplying customers in Larne and Greater Belfast with natural gas in 1996 via the newly constructed Scotland-Northern Ireland pipeline.[183] Rates in Belfast (and the rest of Northern Ireland) were reformed in April 2007. The discrete capital value system means rates bills are determined by the capital value of each domestic property as assessed by the Valuation and Lands Agency.[186] The recent dramatic rise in house prices has made these reforms unpopular.[187]

Health care

The Belfast Health & Social Care Trust is one of five trusts that were created on 1 April 2007 by the Department of Health. Belfast contains most of Northern Ireland's regional specialist centres.[188] The Royal Victoria Hospital is an internationally renowned centre of excellence in trauma care and provides specialist trauma care for all of Northern Ireland.[189] It also provides the city's specialist neurosurgical, ophthalmology, ENT, and dentistry services. The Belfast City Hospital is the regional specialist centre for haematology and is home to a cancer centre that rivals the best in the world.[190] The Mary G McGeown Regional Nephrology Unit at the City Hospital is the kidney transplant centre and provides regional renal services for Northern Ireland.[191] Musgrave Park Hospital in south Belfast specialises in orthopaedics, rheumatology, sports medicine and rehabilitation. It is home to Northern Ireland's first Acquired Brain Injury Unit, costing £9 million and opened by Charles, Prince of Wales and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall in May 2006.[192] Other hospitals in Belfast include the Mater Hospital in north Belfast and the Children's Hospital.

Transport

Belfast is a relatively car-dependent city by European standards, with an extensive road network including the 22.5 miles (36 km) M2 and M22 motorway route.[193] A 2005 survey of how people travel in Northern Ireland showed that people in Belfast made 77% of all journeys by car, 11% by public transport and 6% on foot.[194] It showed that Belfast has 0.70 cars per household compared to figures of 1.18 in the East and 1.14 in the West of Northern Ireland.[194] A road improvement-scheme in Belfast began early in 2006, with the upgrading of two junctions along the Westlink dual-carriageway to grade-separated standard. The improvement scheme was completed five months ahead of schedule in February 2009, with the official opening taking place on 4 March 2009.[195]

Commentators have argued that this may create a bottleneck at York Street, the next at-grade intersection, until that too is upgraded. On 25 October 2012 the stage 2 report for the York Street intersection was approved[196] and in December 2012 the planned upgrade moved into stage 3 of the development process. If successfully completing the necessary statutory procedures, work on a grade separated junction to connect the Westlink to the M2/M3 motorways is scheduled to take place between 2014 and 2018,[197] creating a continuous link between the M1 and M2, the two main motorways in Northern Ireland.

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_2223181.jpg.webp)

Black taxis are common in the city, operating on a share basis in some areas.[198] These are outnumbered by private hire taxis. Bus and rail public transport in Northern Ireland is operated by subsidiaries of Translink. Bus services in the city proper and the nearer suburbs are operated by Translink Metro, with services focusing on linking residential districts with the city centre on 12 quality bus corridors running along main radial roads,[199]

More distant suburbs are served by Ulsterbus. Northern Ireland Railways provides suburban services along three lines running through Belfast's northern suburbs to Carrickfergus, Larne and Larne Harbour, eastwards towards Bangor and south-westwards towards Lisburn and Portadown. This service is known as the Belfast Suburban Rail system. Belfast is linked directly to Coleraine, Portrush and Derry. Belfast has a direct rail connection with Dublin called Enterprise which is operated jointly by NIR and Iarnród Éireann, the state railway company of the Republic of Ireland. There are no rail services to cities in other countries of the United Kingdom, due to the lack of a bridge or tunnel connecting Great Britain to the island of Ireland. There is, however, a combined ferry and rail ticket between Belfast and cities in Great Britain, which is referred to as Sailrail.[200]

In April 2008, the Department for Regional Development reported on a plan for a light-rail system, similar to that in Dublin. The consultants said Belfast does not have the population to support a light rail system, suggesting that investment in bus-based rapid transit would be preferable. The study found that bus-based rapid transit produces positive economic results, but light rail does not. The report by Atkins & KPMG, however, said there would be the option of migrating to light rail in the future should the demand increase.[202][203]

The city has two airports: Belfast International Airport offering, domestic, European and international flights such as Orlando operated seasonally by Virgin Atlantic. The airport is located northwest of the city, near Lough Neagh, while the George Best Belfast City Airport, which is closer to the city centre by train from Sydenham on the Bangor Line, adjacent to Belfast Lough, offers UK domestic flights and a few European flights. In 2005, Belfast International Airport was the 11th busiest commercial airport in the UK, accounting for just over 2% of all UK terminal passengers while the George Best Belfast City Airport was the 16th busiest and had 1% of UK terminal passengers. The Belfast – Liverpool route is the busiest domestic flight route in the UK excluding London with 555,224 passengers in 2009. Over 2.2 million passengers flew between Belfast and London in 2009.[204]

Belfast has a large port used for exporting and importing goods, and for passenger ferry services. Stena Line runs regular routes to Cairnryan in Scotland using its conventional vessels—with a crossing time of around 2 hours 15 minutes. Until 2011 the route went to Stranraer and used inter alia a HSS (High Speed Service) vessel—with a crossing time of around 90 minutes. Stena Line also operates a route to Liverpool. A seasonal sailing to Douglas, Isle of Man is operated by the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company.

The Glider bus service is a new form of transport in Belfast. Introduced in 2018, it is a bus rapid transit system linking East Belfast, West Belfast and the Titanic Quarter from the City Centre.[205] Using articulated buses, the £90 million service saw a 17% increase in its first month in Belfast, with 30,000 more people using the Gliders every week. The service is being recognised as helping to modernise the city's public transport.[206]

National Cycle Route 9 to Newry,[207] which will eventually connect with Dublin,[208] starts in Belfast.

Culture

Belfast's population is evenly split between its Protestant and Catholic residents.[141] These two distinct cultural communities have both contributed significantly to the city's culture. Throughout the Troubles, Belfast artists continued to express themselves through poetry, art and music. In the period since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, Belfast has begun a social, economic and cultural transformation giving it a growing international cultural reputation.[209] In 2003, Belfast had an unsuccessful bid for the 2008 European Capital of Culture. The bid was run by an independent company, Imagine Belfast, who boasted that it would "make Belfast the meeting place of Europe's legends, where the meaning of history and belief find a home and a sanctuary from caricature, parody and oblivion."[210] According to The Guardian the bid may have been undermined by the city's history and volatile politics.[211]

In 2004–05, art and cultural events in Belfast were attended by 1.8 million people (400,000 more than the previous year). The same year, 80,000 people participated in culture and other arts activities, twice as many as in 2003–04.[212] A combination of relative peace, international investment and an active promotion of arts and culture is attracting more tourists to Belfast than ever before. In 2004–05, 5.9 million people visited Belfast, a 10% increase from the previous year, and spent £262.5 million.[212]

The Ulster Orchestra, based in Belfast, is Northern Ireland's only full-time symphony orchestra and is well renowned in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1966, it has existed in its present form since 1981, when the BBC Northern Ireland Orchestra was disbanded.[213] The music school of Queen's University is responsible for arranging a notable series of lunchtime and evening concerts, often given by renowned musicians which are usually given in The Harty Room at the university (University Square).

Musicians and bands who have written songs about or dedicated to Belfast include

U2, Van Morrison, Snow Patrol, Simple Minds, Elton John, Rogue Male, Katie Melua, Boney M, Paul Muldoon, Stiff Little Fingers, Nanci Griffith, Glenn Patterson, Orbital, James Taylor, Fun Boy Three, Spandau Ballet, The Police, Barnbrack, Gary Moore, Neon Neon, Toxic Waste, Energy Orchard, and Billy Bragg.

Belfast has a longstanding underground club scene which was established in the early 1980s.[214]

Belfast has the highest concentration of Irish-speakers in Northern Ireland. Like all areas of the island of Ireland outside of the Gaeltacht, the Irish language in Belfast is not that of an unbroken intergenerational transmission. Due to community activity in the 1960s, including the establishment of the Shaw's Road Gaeltacht community, the expanse in the Irish language arts, and the advancements made in the availability of Irish medium education throughout the city, it can now be said that there is a 'mother-tongue' community of speakers. The language is heavily promoted in the city and is particularly visible in the Falls Road area, where the signs on both the iconic black taxis and on the public buses are bilingual.[215] Projects to promote the language in the city are funded by various sources, notably Foras na Gaeilge, an all-Ireland body funded by both the Irish and British governments. There are a number of Irish language Primary schools and one secondary school in Belfast. The provision of certain resources for these schools (for example, such as the provision of textbooks) is supported by the charitable organisation TACA.

In late August 2018, at least three groups were vying for the right to purchase the 5,500 RMS Titanic relics that were an asset of the bankrupt Premier Exhibitions. One of the offers was by a group including the National Maritime Museum and National Museums Northern Ireland, with assistance by James Cameron.[216] Oceanographer Robert Ballard said he favored this bid since it would ensure that the memorabilia would be permanently displayed in Belfast (where the Titanic was built) and in Greenwich. A decision as to the outcome was to be made by a United States district court judge.[217]

Media

Belfast is the home of the Belfast Telegraph, Irish News, and The News Letter, the oldest English-language daily newspaper in the world still in publication.[218][219] The Belfast Telegraph was founded in 1827 as the Belfast Daily News and later became The Northern Star. In 1961, it was purchased by the Daily Express Group, which owned the paper until 1986. Today, it is part of Trinity Mirror. Belfast Telegraphy is a popular news website in the United Kingdom. It was founded by John Allen and was owned by Johnston Press until it was sold to Trinity Mirror in 2011.

The city is the headquarters of BBC Northern Ireland, ITV station UTV and commercial radio stations Q Radio and U105. Two community radio stations, Blast 106 and Irish-language station Raidió Fáilte, broadcast to the city from west Belfast, as does Queen's Radio, a student-run radio station which broadcasts from Queen's University Students' Union.

One of Northern Ireland's two community TV stations, NvTv, is based in the Cathedral Quarter of the city. There are two independent cinemas in Belfast: the Queen's Film Theatre and the Strand Cinema, which host screenings during the Belfast Film Festival and the Belfast Festival at Queen's. Broadcasting only over the Internet is Homely Planet, the Cultural Radio Station for Northern Ireland, supporting community relations.[220]

The city has become a popular film location; The Paint Hall at Harland and Wolff has become one of the UK Film Council's main studios. The facility comprises four stages of 16,000 square feet (1,500 m2). Shows filmed at The Paint Hall include the film City of Ember (2008) and HBO's Game of Thrones series (beginning in late 2009).

In November 2011, Belfast became the smallest city to host the MTV Europe Music Awards.[221] The event was hosted by Selena Gomez and celebrities such as Justin Bieber, Jessie J, Hayden Panettiere, and Lady Gaga travelled to Northern Ireland to attend the event, held in the Odyssey Arena.[222]

Sports

Belfast has several notable sports teams playing a diverse variety of sports such as football, Gaelic games, rugby, cricket, and ice hockey. The Belfast Marathon is run annually on May Day, and attracted 20,000 participants in 2011.[223]

The Northern Ireland national football team, ranked 59th as of October 2022 in the FIFA World Rankings,[224] plays its home matches at Windsor Park. The 2017–18 Irish League champions Crusaders are based at Seaview, in the north of the city. Other senior clubs are Glentoran, Linfield, Cliftonville, Harland & Wolff Welders and PSNI. Intermediate-level clubs are: Dundela, Newington Youth, Queen's University and Sport & Leisure Swifts, who compete in the NIFL Premier Intermediate League; Albert Foundry, Bloomfield, Colin Valley, Crumlin Star, Dunmurry Rec., Dunmurry Young Men, East Belfast, Grove United, Immaculata, Iveagh United, Malachians, Orangefield Old Boys, Rosario Youth Club, St Luke's, St Patrick's Young Men, Shankill United, Short Brothers and Sirocco Works of the Dunmurry Young Men Northern Amateur Football League and Brantwood and Donegal Celtic of the Ballymena & Provincial League.

Belfast was the home town of former Manchester United player George Best, the 1968 European Footballer of the Year, who died in November 2005. On the day he was buried in the city, 100,000 people lined the route from his home on the Cregagh Road to Roselawn cemetery.[225] Since his death the City Airport was named after him and a trust has been set up to fund a memorial to him in the city centre.[226]

Belfast is home to over twenty Gaelic football and hurling clubs.[227] Casement Park in west Belfast, home to the Antrim county teams, has a capacity of 32,000 which makes it the second largest Gaelic Athletic Association ground in Ulster.[228] In May 2020, the foundation of East Belfast GAA returned Gaelic Games to unionist East Belfast after decades of its absence in the area. The current club president is Irish-language enthusiast Linda Ervine who comes from a unionist background in the area. The team currently plays in the Down Senior County League.[229]

The 1999 Heineken Cup champions Ulster Rugby play at Ravenhill Stadium in the south of the city. Belfast has four teams in rugby's All-Ireland League: Belfast Harlequins in Division 1B; and Instonians, Queen's University and Malone in Division 2A.

Belfast is home to the Stormont cricket ground since 1949 and was the venue for the Irish cricket team's first ever One Day International against England in 2006.[230]

Belfast is home to one of the biggest ice hockey clubs in the United Kingdom, the Belfast Giants. The Giants were founded in 2000 and play their games at the 9,500 capacity SSE Arena, where crowds normally range from 4,000 to 7,000. Many ex-NHL players have featured on the Giants roster, none more famous than world superstar Theo Fleury. The Giants play in the 10-team professional Elite Ice Hockey League which is the top league in the United Kingdom. The Giants have been league champions 6 times, most recently in the 2021–22 season. The Belfast Giants are a huge brand in Northern Ireland and their increasing stature in the game led to the Belfast Giants playing the Boston Bruins of the NHL on 2 October 2010 at the SSE Arena in Belfast, losing the game 5–1.

Other significant sportspeople from Belfast include double world snooker champion Alex "Hurricane" Higgins[231] and world champion boxers Wayne McCullough, Rinty Monaghan and Carl Frampton.[232] Leander ASC is a well known swimming club in Belfast. Belfast produced the Formula One racing stars John Watson who raced for five different teams during his career in the 1970s and 1980s and Ferrari driver Eddie Irvine.

Notable people

Academia and science

- John Stewart Bell, physicist

- Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell, astrophysicist

- John Boyd Dunlop, inventor

- Lord Kelvin, physicist and engineer

Arts and media

- Anthony Boyle, actor

- Sir Kenneth Branagh, actor[233]

- Gordon Burns, journalist, gameshow host, best known for The Krypton Factor

- Ciaran Carson, writer

- Frank Carson, comedian[234]

- Jamie Dornan, actor

- Barry Douglas, musician

- James Galway, musician

- Eamonn Holmes, broadcaster[235]

- Brian Desmond Hurst, film director

- Oliver Jeffers, artist

- C. S. Lewis, author[236]

- Paula Malcomson, actress

- Gerry McAvoy, musician and long time bass guitarist with Rory Gallagher

- Gary Moore, guitarist

- Van Morrison, singer-songwriter

- Doc Neeson, singer-songwriter

- Patricia Quinn, actress

- Roy Walker (comedian), gameshow host, best known for Catchphrase

Politics

- Gerry Adams. politician

- Lord Craigavon, former Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

- Abba Eban (1915–2002), Israeli diplomat and politician, and President of the Weizmann Institute of Science

- Chaim Herzog, former President of Israel

- Mary McAleese, former President of Ireland

- Peter Robinson, former First Minister of Northern Ireland

- Lord Trimble, former First Minister of Northern Ireland, Nobel Peace Prize winner

Sports

- Paddy Barnes, boxer, Olympic Games Bronze Medalist

- George Best, football player, Ballon D'or winner

- Danny Blanchflower, football player and manager

- Jackie Blanchflower, football player

- Chris Brunt, football player

- Ryan Burnett, boxer

- Anthony Cacace, boxer

- Craig Cathcart, football player

- Michael Conlan, boxer

- P. J. Conlon, baseball player

- Killian Dain, professional wrestler

- Mal Donaghy, football player

- Corry Evans, football player

- Jonny Evans, football player

- Dave Finlay, professional wrestler

- Carl Frampton, boxer

- Craig Gilroy, rugby union player

- Alex Higgins, snooker player

- Paddy Jackson, rugby union player

- Wayne McCullough, WBC World Champion Boxer, Olympic Games Silver Medalist

- Alan McDonald, football player

- Rory McIlroy, golfer

- Sammy McIlroy, football player and manager

- Eamon Magee, boxer

- Brian Magee, boxer

- Jim Magilton, football player and manager

- Rinty Monaghan, World Flyweight boxing champion

- Owen Nolan, hockey player, Olympic gold medalist

- Lady Mary Peters, Olympic gold medalist athlete

- Tommy Robb, Grand Prix motorcycle road racer

- Pat Rice, football player and coach

- Joe Swail, snooker player

- Gary Wilson, cricketer

Other

- Patrick Carlin, Victoria Cross recipient

- Shaw Clifton, former General of The Salvation Army

- Dame Rotha Johnston, entrepreneur

- James Joseph Magennis, Victoria Cross recipient

- Jonathan Simms, victim of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD), noted for unprecedented survival rate of a decade with the disease

- Rosemary Church, newsanchor

Education

Belfast has two universities. Queen's University Belfast was founded in 1845 and is a member of the Russell Group, an association of 24 leading research-intensive universities in the UK.[237] It is one of the largest universities in the UK with 25,231 undergraduate and postgraduate students spread over 250 buildings, 120 of which are listed as being of architectural merit.[238]

Ulster University, created in its current form in 1984, is a multi-centre university with a campus in the Cathedral Quarter of Belfast. The Belfast campus has a specific focus on Art and Design and Architecture, and is currently undergoing major redevelopment. The Jordanstown campus, just seven miles (11 km) from Belfast city centre concentrates on engineering, health and social science. The Coleraine campus, about 55 mi (89 km) from Belfast city centre concentrates on a broad range of subjects. Course provision is broad – biomedical sciences, environmental science and geography, psychology, business, the humanities and languages, film and journalism, travel and tourism, teacher training and computing are among the campus strengths. The Magee campus, about 70 mi (113 km) from Belfast city centre has many teaching strengths; including business, computing, creative technologies, nursing, Irish language and literature, social sciences, law, psychology, peace and conflict studies and the performing arts. The Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN) Web Service receives funding from both universities and is a rich source of information and source material on the Troubles as well as society and politics in Northern Ireland.[239]

Belfast Metropolitan College is a large further education college with three main campuses around the city, including several smaller buildings. Formerly known as Belfast Institute of Further and Higher Education, it specialises in vocational education. The college has over 53,000 students enrolled on full-time and part-time courses, making it one of the largest further education colleges in the UK and the largest in the island of Ireland.[240]

The Belfast Education and Library Board was established in 1973 as the local council responsible for education, youth and library services within the city.[241] In 2006, this board became part of the Education Authority for Northern Ireland. There are 184 primary, secondary and grammar schools in the city.[242]

Tourism

Belfast is one of the most visited cities in the UK,[243] and the second most visited on the island of Ireland.[244] In 2008, 7.1 million tourists visited the city.[245] Numerous tour bus companies and boat tours run there throughout the year, including tours based on the series Game of Thrones, which has had various filming locations around Northern Ireland.[246]

Frommer's, the American travel guidebook series, listed Belfast as the only United Kingdom destination in its Top 12 Destinations to Visit in 2009. The other listed destinations were Berlin (Germany), Cambodia, Cape Town (South Africa), Cartagena (Colombia), Istanbul (Turkey), the Lassen Volcanic National Park (US), Saqqara (Egypt), the Selma To Montgomery National Historic Trail (US), Waiheke Island (New Zealand), Washington, D.C. (US), and Waterton Lakes National Park (Canada).[247]

Belfast City Council is currently investing into the complete redevelopment of the Titanic Quarter, which is planned to consist of apartments, hotels, and a riverside entertainment district. A major visitor attraction, Titanic Belfast is a monument to Belfast's maritime heritage on the site of the former Harland & Wolff shipyard, opened on 31 March 2012. It features a criss-cross of escalators and suspended walkways and nine high-tech galleries.[248] They also hope to invest in a new modern transport system (including high-speed rail and others) for Belfast, with a cost of £250 million.[249]

In 2018, six hotels were opened, with the biggest in Northern Ireland, the £53 million Grand Central Hotel Belfast officially open to the public. The other hotels included AC Marriot, Hampton By Hilton, EasyHotel, Maldron Belfast City Centre and Flint. The new hotels have helped to increase a further 1,000 bedrooms in the city.[250] Belfast was successful in attracting many conferencing events, both national and international, to the city in 2018. Over 60 conferences took place that year with 30,000 people helping contribute to a record 45 million pounds for the local economy.[250]

There is a tourist information centre located at Donegall Square North.[251]

Twin towns – sister cities

Belfast City Council takes part in the twinning scheme,[252] and is twinned with the following sister cities:

- Nashville, Tennessee, United States (since 1994)[252]

- Hefei, Anhui Province, China (since 2005)[252]

- Boston, Massachusetts, United States (since 2014)[252]

- Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China (since 2016)[253]

Freedom of the City

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Belfast.

Individuals