Olaf Scholz

Olaf Scholz (German: [ˈoːlaf ˈʃɔlts] (![]() listen); born 14 June 1958) is a German politician who has served as the chancellor of Germany since 8 December 2021. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he previously served as Vice Chancellor under Angela Merkel and as Federal Minister of Finance from 2018 to 2021. He was also First Mayor of Hamburg from 2011 to 2018 and deputy leader of the SPD from 2009 to 2019.

listen); born 14 June 1958) is a German politician who has served as the chancellor of Germany since 8 December 2021. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he previously served as Vice Chancellor under Angela Merkel and as Federal Minister of Finance from 2018 to 2021. He was also First Mayor of Hamburg from 2011 to 2018 and deputy leader of the SPD from 2009 to 2019.

Olaf Scholz MdB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Scholz in 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of Germany | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Incumbent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assumed office 8 December 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice Chancellor |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Angela Merkel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice Chancellor of Germany | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 March 2018 – 8 December 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Angela Merkel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sigmar Gabriel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Robert Habeck | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Finance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 March 2018 – 8 December 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Angela Merkel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Wolfgang Schäuble | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Christian Lindner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Mayor of Hamburg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 March 2011 – 13 March 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Second Mayor | Dorothee Stapelfeldt Katharina Fegebank | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Christoph Ahlhaus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Peter Tschentscher | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 14 June 1958 Osnabrück, Lower Saxony, West Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Social Democratic Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Britta Ernst (m. 1998) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence(s) | Federal Chancellery, Berlin, flats in Hamburg and Potsdam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Hamburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | olaf-scholz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scholz began his career as a lawyer specialising in labour and employment law. He became a member of the SPD in the 1970s and was a member of the Bundestag from 1998 to 2011. Scholz served in the Hamburg Government under First Mayor Ortwin Runde in 2001, before his election as General Secretary of the SPD in 2002, serving alongside SPD leader and then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder. He became his party's Chief Whip in the Bundestag, later entering the First Merkel Government in 2007 as Minister of Labour and Social Affairs. After the SPD quit the government following the 2009 election, Scholz returned to lead the SPD in Hamburg, and was elected Deputy Leader of the SPD. He led his party to victory in the 2011 Hamburg state election, and became First Mayor, holding that position until 2018.

After the Social Democratic Party entered the Fourth Merkel Government in 2018, Scholz was appointed as both Minister of Finance and Vice Chancellor of Germany. In 2020, he was nominated as the SPD's candidate for Chancellor of Germany for the 2021 federal election. The party won a plurality of seats in the Bundestag and formed a "traffic light coalition" with Alliance 90/The Greens and the Free Democratic Party. On 8 December 2021, Scholz was elected and sworn in as Chancellor by the Bundestag.

As Chancellor, Scholz oversaw Germany's response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Despite having a much more restrained and cautious response than that of other Western countries, Scholz oversaw an increase in the German defense budget, weapons shipments to Ukraine, and a discontinuance of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. Scholz set out the principles of a new German defence policy in his Zeitenwende speech.

Early life and education

Scholz was born on 14 June 1958, in Osnabrück, Lower Saxony, but grew up in Hamburg's Rahlstedt district.[3] His parents worked in the textile industry.[4] He has two younger brothers, Jens Scholz, an anesthesiologist and CEO of the University Medical Center Schleswig Holstein;[5] and Ingo Scholz, a tech entrepreneur. Olaf Scholz attended the Bekassinenau elementary school in Oldenfelde but then switched to the Großlohering elementary school in Großlohe. After graduating from high school in 1977, he began studying law at the University of Hamburg in 1978 as part of a one-stage legal training course.[6] He later found employment as a lawyer specialising in labour and employment law, working at the law firm Zimmermann, Scholz und Partner.[7] Scholz joined the Social Democratic Party at the age of 17.[3]

Scholz's family is traditionally Lutheran and he was baptized in the Evangelical Church in Germany; he holds largely secular views and left the Church in adulthood, but has called for appreciation of the country's Christian heritage and culture.[8]

Political career

Young socialist, 1975–1989

Scholz joined the SPD in 1975 as a student, where he got involved with the Jusos, the youth organization of the SPD. From 1982 to 1988, he was Deputy Federal Juso Chairman, and from 1987 to 1989 also Vice President of the International Union of Socialist Youth. He supported the Freudenberger Kreis, the Marxist wing of the Juso university groups, promoting "overcoming the capitalist economy" in articles.[9] In it, Scholz criticized the "aggressive-imperialist NATO", the Federal Republic as the "European stronghold of big business" and the social-liberal coalition, which puts the "bare maintenance of power above any form of substantive dispute".[10] On 4 January 1984, Scholz and other Juso leaders met in the GDR with Egon Krenz, the secretary of the Central Committee of the SED and member of the Politburo of the SED-Central Committee, Herbert Häber. In 1987, Scholz crossed the inner-German border again and stood up for disarmament agreements as Juso-Vice at an FDJ peace rally in Wittenberg.[11]

Member of the Bundestag, 1998–2001

A former vice president of the International Union of Socialist Youth, Scholz was first elected to represent Hamburg-Altona in the Bundestag in 1998, aged 40.[12] Scholz served on the Committee for Labor and Social Matters. In the committee of inquiry into the visa affair of the Bundestag, he was chairman of the SPD parliamentary group.[13] Scholz resigned his mandate on 6 June 2001, to take office as Senator. Because his seat was an overhang seat, it was not filled until the 2002 German federal election.

Senator for the Interior of Hamburg, 2001

On 30 May 2001, Scholz succeeded Senator for the Interior of Hamburg, Hartmuth Wrocklage, in the Senate of Hamburg led by Mayor Ortwin Runde. Wrocklage had resigned due to allegations of nepotism. He also followed Wrocklage as Deputy Member of the Bundesrat.

During his brief time as Senator, he controversially approved the forced use of emetics to gather evidence from suspected drug dealers.[14] The Hamburg Medical Chamber expressed disapproval of this practice due to potential health risks.[15]

He left office in October 2001, after the defeat of his party at the 2001 Hamburg state election and the election of Ole von Beust as First Mayor. His successor was Ronald Schill,[16][17] who had won on a Law and order platform, with an emphasis on harsh penalties for drug dealers.

Member of the Bundestag, 2002–2011

Scholz was elected again to the Bundestag in the 2002 German federal election. From 2002 to 2004, Scholz also served as General Secretary of the SPD; he resigned from that office when party leader and Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, facing disaffection within his own party and hampered by persistently low public approval ratings, announced he would step down as Leader of the Social Democratic Party.[18]

Scholz was one of a series of politicians who sparked debate over the German journalistic norm of allowing interviewees to "authorize" and amend quotes before publication, after his press team insisted on heavily rewriting an interview with Die Tageszeitung in 2003.[19][20] Editor Bascha Mika condemned the behavior as a "betrayal of the claim to a free press" and the newspaper ultimately published the interview with Scholz's answers blacked out.[21][22]

Scholz served as the SPD spokesperson on the inquiry committee investigating the German Visa Affair in 2005. Following the federal election later that year, he served as First Parliamentary Secretary of the SPD Bundestag Group, becoming Chief Whip of the Social Democratic Party. In this capacity, he worked closely with the CDU Chief Whip Norbert Röttgen to manage and defend the grand coalition led by Chancellor Angela Merkel in the Bundestag.[23] He also served as a member of the Parliamentary Oversight Panel, which provides parliamentary oversight of the German intelligence services; the BND, MAD and BfV.[24]

Scholz resigned from his Bundestag mandate on 10 March 2011, three days after he had been elected as First Mayor of Hamburg.[25]

Minister of Labour and Social Affairs, 2007–2009

In 2007, Scholz joined the Merkel Government, succeeding Franz Müntefering as Minister of Labour and Social Affairs.[26][27]

Following the 2009 federal election, when the SPD left the Government, Scholz was elected as Deputy Leader of the SPD, replacing Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Between 2009 and 2011, he was also a member of the SPD group's Afghanistan/Pakistan Task Force.[28] In 2010, he participated in the annual Bilderberg Meeting in Sitges, Spain.[29]

First Mayor of Hamburg, 2011–2018

In 2011, Scholz was the lead SPD candidate at the Hamburg state election, which the SPD won with 48.3 per cent of the votes, taking 62 of 121 seats in the Hamburg Parliament.[30] Scholz resigned as a Member of the Bundestag on 11 March 2011, days after his formal election as First Mayor of Hamburg; Dorothee Stapelfeldt, also a Social Democrat, was appointed his Deputy First Mayor.[31][32][33]

In his capacity as First Mayor, Scholz represented Hamburg and Germany internationally. On 7 June 2011, Scholz attended the state dinner hosted by President Barack Obama in honor of Chancellor Angela Merkel at the White House.[34] As host of Hamburg's annual St. Matthias' Day banquet for the city's civic and business leaders, he invited several high-ranking guests of honour to the city, including Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault of France (2013), Prime Minister David Cameron of the United Kingdom (2016), and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada (2017).[35] From 2015 until 2018, he also served as Commissioner of the Federal Republic of Germany for Cultural Affairs under the Treaty on Franco-German Cooperation.[36]

.jpg.webp)

In 2013, Scholz opposed a public initiative aiming at a complete buyback of energy grids that the city of Hamburg had sold to utilities Vattenfall Europe AG and E.ON decades before; he argued this would overburden the city, whose debt stood at more than 20 billion euros at the time.[37]

Scholz was asked to participate in exploratory talks between the CDU, CSU and SPD parties to form a coalition government following the 2013 federal election.[38] In the subsequent negotiations, he led the SPD delegation in the financial policy working group; his co-chair from the CDU/CSU was Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble.[39] Alongside fellow Social Democrats Jörg Asmussen and Thomas Oppermann, Scholz was reported in the media to be a possible successor to Schäuble in the post of Finance Minister at the time; whilst Schäuble remained in post, the talks to form a coalition were ultimately successful.[40]

In a paper compiled in late 2014, Scholz and Schäuble proposed redirecting revenue from the so-called solidarity surcharge on income and corporate tax (Solidaritätszuschlag) to subsidize the federal states’ interest payments.[41]

Under Scholz's leadership, the Social Democrats won the 2015 state election in Hamburg, receiving around 47 per cent of the vote.[42] He formed a coalition government with the Green Party, with Green leader Katharina Fegebank serving as Deputy First Mayor.[43][44]

In 2015, Scholz led Hamburg's bid to host the 2024 Summer Olympics with an estimated budget of 11.2 billion euros ($12.6 billion), competing against Los Angeles, Paris, Rome, and Budapest; the citizens of Hamburg, however, later rejected the city's candidacy in a referendum, with more than half voting against the project.[45][46] Later that year, Scholz – alongside Minister-President Torsten Albig of Schleswig-Holstein – negotiated a debt-restructuring deal with the European Commission that allowed the German regional lender HSH Nordbank to offload 6.2 billion euros in troubled assets – mainly non-performing ship loans – onto its government majority owners and avoid being shut down, saving around 2,500 jobs.[47]

In 2017, Scholz received criticism over his handling of riots that took place during the G20 summit in Hamburg.[7]

Scholz has been criticized in November and December 2021 for emerging details about his handling of the CumEx tax fraud at M. M. Warburg & Co. when he was the mayor of Hamburg.[48][49]

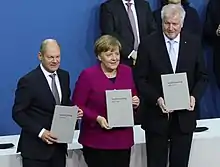

Vice Chancellor and Minister of Finance, 2018–2021

After a lengthy period of government formation following the 2017 federal election, during which the CDU, CSU and SPD agreed to continue in coalition, Scholz was accepted by all parties as Federal Minister of Finance. Scholz was sworn in alongside the rest of the Government on 14 March 2018, also taking the role of Vice Chancellor of Germany under Angela Merkel.[50] Within his first months in office, Scholz became one of Germany's most popular politicians, reaching an approval rating of 50 per cent.[51]

In 2019, Scholz ran for leader of the SPD, but lost to Norbert Walter-Borjans.[52]

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, Scholz drafted a series of unprecedented rescue packages for the country's economy, including a 130 billion euro stimulus package in June 2020, which thanks to generous lifelines for businesses and freelancers, as well as a decision to keep factories open, avoided mass layoffs and weathered the crisis better than neighbours such as Italy and France.[53][54] Scholz also oversaw the implementation of the Next Generation EU, the European Union's 750 billion euro recovery fund to support member states hit by the pandemic, including the decision to spend 90 per cent of the 28 billion euros for Germany on climate protection and digitalization.[55]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

With France, Scholz drove efforts to introduce a global corporate minimum tax and new tax rules for tech giants.[56][57]

At the G7 summit in June 2021, the G7 agreed on a worldwide minimum tax proposed by Scholz of at least 15 per cent for multinational companies. The main reason why all G7 member states were in favour was that Scholz was able to convince US President Joe Biden, unlike his predecessor Donald Trump, of the minimum taxation.[58] Also in June 2021, Scholz had the Federal Central Tax Office purchase information about potential tax evaders from Dubai. It is data from millions of German taxpayers and contains information on assets hidden from the tax authorities in Dubai. The data should serve to uncover cross-border tax offenses on a significant scale.[59]

Scholz is criticized in the context of the bankruptcy of the payment service provider Wirecard, as there have been serious misconduct by the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin).[60] Critics complain that the Federal Ministry of Finance is responsible for monitoring BaFin.[61] During Scholz's time in office, the Ministry of Finance was one of the subjects of parliamentary inquiry into the so-called Wirecard scandal, in the process of which Scholz denied any responsibility[62][63] but replaced regulator BaFin's president Felix Hufeld and vowed to strengthen financial market supervision.[64][65]

Candidate for party co-leadership, 2019

In June 2019, Scholz initially ruled out a candidacy for the party co-leadership following the resignation of Andrea Nahles. He explained that a simultaneous activity as Federal Minister of Finance and leader was "not possible in terms of time".[66][67][68] In August Scholz announced that he wanted to run for party chairmanship in a duo with Klara Geywitz.[69][70] He justified this with the fact that many of those he considered suitable did not run for office and a resulting responsibility.[71] The team of Klara Geywitz and Olaf Scholz received after the first round of the membership decision on 26 October 2019, with 22.7 percent, the highest share of the six candidate duos standing for election. It qualified for the runoff election with the second-placed team Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans, which received 21.0 percent of the vote.[72]

On 30 November 2019, it was announced that Esken and Walter-Borjans had received 53.1 percent of the vote in the runoff election, Geywitz and Scholz only 45.3 percent.[73] This was seen as an upset victory for the left-wing of the SPD, including skeptics of the grand coalition with the CDU. Esken and Walter-Borjans were little-known to the public at large, Esken being a backbencher in the Bundestag and Walter-Borjans being the former Minister of Finance of North Rhine-Westphalia from 2010 to 2017. Scholz on the other hand had the backing of much of the party establishment.

Chancellor candidate, 2021

On 10 August 2020, the SPD party executive agreed that it would nominate Scholz to be the party's candidate for Chancellor of Germany at the 2021 federal election.[74] Scholz belongs to the centrist wing of the SPD,[75] and his nomination was seen by Die Tageszeitung as marking the decline of the party's left.[76] Scholz led the SPD to a narrow victory in the election, winning 25.8 per cent of the vote and 206 seats in the Bundestag.[77] Following this victory, he was widely considered to be the most likely next Chancellor of Germany in a so-called traffic light coalition with The Greens and the Free Democratic Party (FDP).[78] On 24 November, the SPD, Green and FDP reached a coalition agreement with Scholz as the new German chancellor.[79]

Chancellor of Germany, 2021–present

Scholz in 2021 | |

| Chancellorship of Olaf Scholz 8 December 2021 – present | |

Olaf Scholz | |

| Cabinet |

|

| Party | Social Democratic Party |

| Election |

|

| Nominated by | Bundestag |

| Appointed by |

|

| Seat |

|

|

| |

Scholz was elected Chancellor by the Bundestag on 8 December 2021, with 395 votes in favour and 303 against.[80] His new government was appointed on the same day by President Frank-Walter Steinmeier.[81] At 63 years, 177 days of age, Scholz is the oldest person to become Chancellor of Germany since Ludwig Erhard who was 66 years, 255 days old when he assumed office on 17 October 1963.

Scholz came to Warsaw in December 2021 for talks with Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. They discussed the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which would bring Russian gas under the Baltic Sea to Germany bypassing Poland, and Poland's dispute with the EU over the rule of law and the primacy of European Union law. Scholz backed Poland's efforts to stop the flow of migrants seeking entry from Belarus.[82]

Scholz extended into 2022 the suspension of the sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia.[83] The decision was made to "no longer approve any export sales to countries as long as they are directly involved" in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.[84] In September 2022, Scholz visited the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, seeking to deepen ties with the Arab states of the Persian Gulf and find alternative sources of energy.[85] Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman received Scholz in Jeddah.[86] Scholz's government approved new arms export deals to Saudi Arabia, despite a ban imposed as a result of the Saudi war in Yemen and the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi.[87]

On 22 February 2022, Scholz announced that Germany would be halting its approval of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in response to Russia's recognition of two self-declared separatist republics within Ukraine.[88] Scholz spoke against allowing the EU to cut Russia off from the SWIFT global interbank payment system.[89] In an emergency meeting of Parliament on 27 February, Scholz made an historic speech announcing a complete reversal of German military and foreign policy, including shipping weapons to Ukraine and dramatically increasing Germany's defense budget.[90]

In June 2022, Scholz said that his government remains committed to phasing out nuclear power despite rising energy prices and Germany's dependence on energy imports from Russia.[91] Former Chancellor Angela Merkel committed Germany to a nuclear power phase-out after the Fukushima nuclear disaster.[92]

Energy-intensive German industry and German exporters were hit particularly hard by the 2021–present global energy crisis.[93][94] Scholz said: "Of course we knew, and we know, that our solidarity with Ukraine will have consequences."[95] On 29 September 2022, Germany presented a €200 billion plan to support industry and households.[96]

Political views

Within the SPD, Scholz is widely viewed as being from the moderate wing of the party.[7] Because of his consistent and mechanical-sounding choice of words in press conferences and interviews, Scholz was nicknamed as "the Scholzomat" by the media. In 2013 he said that he found the attribution "very appropriate".[97][98]

After the 2017 federal election, Scholz was publicly critical of party leader Martin Schulz’s strategy and messaging, releasing a paper titled "No excuses! Answer new questions for the future! Clear principles!" With his proposals for reforming the party, he was widely interpreted to position himself as a potential challenger or successor to Schulz within the SPD. In the weeks after his party first started weighing a return to government, Scholz urged compromise and was one of the SPD members more inclined toward another grand coalition.[99]

In January 2019, Scholz had primarily seen China as an economic partner.[100] He tried to persuade Chinese Vice Premier Liu He that China should be more open to German firms.[101] Scholz supported the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China.[102] In September 2022, he condemned the treatment of ethnic Uyghurs in China's Xinjiang.[103]

In October 2019, Scholz condemned the Turkish invasion of the Kurdish-controlled northeastern areas of Syria, otherwise known as Rojava.[104]

Economic and financial policy

Scholz has been campaigning for a financial transaction tax for several years. Experts criticized parts of his plans because they believed that it would primarily affect small shareholders.[105][106][107][108] In December 2019, he pushed the introduction of this tax at European Union level. According to the draft, share purchases should be taxed when it comes to shares in companies that are worth at least one billion euros.[109] Journalist Hermann-Josef Tenhagen criticized this version of the transaction tax because the underlying idea of taxing the wealthy more heavily was in fact turned into the opposite.[110] A report by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy commissioned by the Federal Government in 2020 certified the same deficiencies in the tax concept that Tenhagen had already pointed out.[111]

Since taking office as minister of finance, Scholz has been committed to a continued goal of no new debt and limited public spending.[51] In 2018, he suggested the creation of a European Union-wide unemployment insurance system to make the Eurozone more resilient to future economic shocks.[112]

Environment and climate policy

In September 2019, Scholz negotiated the climate package in a key role for the SPD. To this he said: "What we have presented is a great achievement", whereas climate scientists almost unanimously criticized the result as insufficient.[113][114][115][116][117]

In August 2020, Scholz held a phone call with US Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin, discussing a lift of US sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. In exchange, Scholz offered 1 billion euros in subsidies to liquid gas terminals in northern Germany for US liquid gas imports.[118][119][120] The move has sparked controversy about the SPD's stance towards renewable energy.[121][122]

The revised Climate Protection Act introduced by Olaf Scholz's cabinet as Mayor of Hamburg provides for a 65 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030, an 88 per cent reduction by 2040 and climate neutrality by 2045.[123]

Scholz called for the expansion of renewable energy to replace fossil fuels.[124] In May 2021, Scholz proposed the establishment of an international climate club, which should serve to develop common minimum standards for climate policy measures and a coordinated approach. In addition, uniform rules for the carbon accounting of goods should apply among members.[125]

As part of the coalition agreement that led to Scholz becoming chancellor, the Social Democrats, Free Democrats, and Green parties agreed to accelerate Germany's phaseout of coal to the year 2030, in line with the target set by the Powering Past Coal Alliance. The country's previous target had been to end the use of coal by 2038. In addition, the agreement set a phaseout of power generation from natural gas by 2040. The agreement also included provisions for the prohibition on natural gas heating in new buildings and replacement of natural gas systems in existing buildings. An end to the sale of combustion vehicles would come in 2035, in line with the target set by the European Commission.[126]

COVID-19 vaccine mandate

During his campaign in the 2021 election, Scholz opposed a COVID-19 vaccine mandate. Since late November 2021, he has expressed support for mandatory vaccination for adults, scheduled to be voted during the first months of 2022 by the federal parliament, and for the closure of non-essential retail stores to unvaccinated adults, based on the so-called 2G-Regel, decreed by state governments in December 2021.[127][128][129][130][131]

On 13 January 2022, Scholz told lawmakers in the Bundestag, Germany should make COVID-19 vaccinations mandatory[132] for all adults. Later in the same month, he warned people the coronavirus would not "miraculously" disappear. He said Germany would not be able to get out of the pandemic without compulsory vaccinations.[133] The opposition Christian Democratic Union criticized the government for not taking a firm decision on a vaccine mandate. The far-right Alternative for Germany party wants Scholz's government to ban vaccine mandates.[134]

Relationship with the United States

In December 2019, Scholz criticized the US legislation imposing sanctions on Russia's Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany, saying: "Such sanctions are a serious interference in the internal affairs of Germany and Europe and their sovereignty."[135]

In regards to the relationship with the United States, Scholz agrees with a longstanding agreement that allows American tactical nuclear weapons to be stored and manned on American bases in Germany.[136][137]

Scholz called the US "Europe's closest and most important partner". Upon assuming the chancellorship in December 2021, he stated he would soon be meeting with President Joe Biden, saying: "It is now clear what binds us together."[137] In January 2022, The New York Times reported intensifying concerns from the US and other NATO allies about the Scholz government's "evident hesitation to take forceful measures" against Russia in the 2021–2022 Russo-Ukrainian crisis.[138] The Scholz government initially refused to send weapons to Ukraine, citing existing German financial support for the Eastern European country.[139] On 26 February, following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Scholz reversed his decision and pledged a supply of anti-tank weapons and Stinger missiles to Ukraine.[140]

Relationship with Poland

_3.jpg.webp)

In December 2021, Scholz rejected the Polish government's claim for further World War II reparations.[141] According to the German government, there is no legal basis for further compensation payments.[142] In a meeting with Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki Scholz said: "We have concluded treaties that are valid and have settled the past issues and the compensation".[142] Scholz also pointed out that Germany "continues to be willing to pay very, very high contributions to the EU budget", from which Poland has benefited considerably since its accession to the EU.[142] As a consequence of aggression by Nazi Germany, Poland lost about a fifth of its population and much of Poland was subjected to enormous destruction of its industry and infrastructure.[143][144]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 6 February 2022, Scholz rejected Ukraine's demands for weapons deliveries, saying Germany "has for many years taken the clear stance that we do not deliver to crisis regions."[145]

In response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Scholz greatly altered German spending on defense. On 26 February 2022, Scholz was one of several EU leaders who opposed kicking Russia out of the SWIFT international payment system.[146] On 27 February, Scholz announced the creation of a one-off 100 billion euro fund for the German military.[147] This represents a major shift in German foreign policy, as Germany had long refused to meet the required spending of 2% of its GDP on defense, as is required by NATO.[148] In addition to increasing defense protections for his own country, in an address to Germany's parliament on 23 March, Scholz emphasized support for aiding Ukraine in its resistance to Russian invasion.[149] In this same address, Scholz claimed that Germany would "try everything we can until peace prevails again on our continent" including taking hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees across German borders.[149] While the chancellor avowed that Germany would provide Ukraine with necessary resources,[150] he insisted that NATO will not engage in direct military conflict with Russia.[149]

Amid pressure to prohibit Russian gas imports across Europe, Scholz refused to end German imports of Russian gas.[151] However, in April 2022, Scholz said Germany is working on ending the import of Russian energy.[152] Scholz announced plans to build two new LNG terminals.[153] Scholz's government said it had sealed a long-term agreement with Qatar,[154] one of the world's largest exporters of liquefied natural gas.[155] Scholz also opposed a reversal of Germany's scheduled end to nuclear power, saying the technical challenges are too great.[156]

In April, despite the agreement between Vice Chancellor and Economy Minister Robert Habeck and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, Scholz was yet to take the decision on sending tanks to Ukraine.[157]

On 9 May 2022, Scholz said that Russians and Ukrainians once fought together during World War II against Nazi Germany's "murderous National Socialist regime," but now "Putin wants to overthrow Ukraine and destroy its culture and identity... [and] even regards his barbaric war of aggression as being on a par with the fight against National Socialism. That is a falsification of history and a disgraceful distortion."[158]

On 16 June 2022, Scholz visited the Ukrainian Capital, Kyiv, alongside French President Emmanuel Macron and Italy's Prime Minister Mario Draghi to meet President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. They talked about various issues such as the war in Ukraine and Ukraine's membership into the EU.[159][160] This comes as a reverse of his previous stance to not visit Ukraine, after Zelensky rebuked the German President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier over his contribution to stronger Moscow-Berlin ties.[161][162]

Other activities

International organizations

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), ex-officio member of the board of governors (2018–2021)[163]

- European Investment Bank (EIB), ex-officio member of the board of governors (2018–2021)[164]

- European Stability Mechanism, member of the board of governors (2018–2021)[165]

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), ex-officio member of the board of governors (2018–2021)[166]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), ex-officio alternate member of the board of governors (2018–2021)[167]

Corporate boards

Personal life

Olaf Scholz is married to fellow SPD politician Britta Ernst. The couple lived in Hamburg's Altona district before moving to Potsdam in 2018.[174]

Scholz was raised in the mainstream Protestant Evangelical Church in Germany, but he later left it.[175] At his inauguration as Chancellor in 2021, Scholz took the oath of office without a reference to God (the second Chancellor to do so after Gerhard Schröder) and is the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany to not belong to a Church.[176]

See also

- Senate Scholz II

- Senate Scholz I

References

- https://www.bundesrat.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/plenarprotokolle/2001/Plenarprotokoll-764.pdf;jsessionid=065965D6B0FB687078C6F5FE9A19F6BD.1_cid339?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

- https://www.bundesrat.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/plenarprotokolle/2001/Plenarprotokoll-769.pdf;jsessionid=065965D6B0FB687078C6F5FE9A19F6BD.1_cid339?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

- Cliffe, Jeremy (3 September 2021). "How Olaf Scholz and the SPD could lead Germany's next government". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- Bennhold, Katrin (24 November 2021). "He Convinced Voters He Would Be Like Merkel. But Who Is Olaf Scholz?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- Gammelin, Cerstin (25 June 2020). "Olaf Scholz Bruder: Warum Jens Scholz in Paris berühmt". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Schindler, Fabian (21 March 2011). "Stades Bürgermeister verkündet seinen Abschied". Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Chazan, Guy (9 February 2018). "Olaf Scholz, a sound guardian for Germany's finances". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- "Scholz: Christliche Prägung unserer Kultur wertschätzen". Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Feldenkirchen, Markus; Sauga, Michael (26 November 2007). "Rückkehr eines Bauernopfers". Der Spiegel.

- Greive, Martin; Hildebrand, Jan; Rickens, Christian; Stratmann, Klaus (21 August 2020). "Kann er Kanzler?: Olaf Scholz – ein kritisches Porträt über den Kanzlerkandidaten der SPD". Handelsblatt (in German).

- "Olaf Scholz früher: "Abrüstung jetzt" in SWR2 Archivradio". SWR.de. 24 September 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021.

- "Olaf Scholz, MdB". SPD-Bundestagsfraktion (in German). 18 April 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "DeutschlandRadio Berlin – Interview – Scholz: Politisch Verantwortliche erst später vernehmen". www.deutschlandradio.de. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Olaf Scholz: The Teflon candidate". POLITICO. 23 September 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- "Kein ärztlicher Eingriff mit Gewalt" [No forced medical intervention]. Pressestelle der Ärztekammer Hamburg (in German). 30 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "Ronald Schill: Chronik einer kurzen Polit-Karriere". Manager-Magazin (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Gärtner, Birgit (28 May 2021). "Olaf Scholz: einst Kapitalismuskritik, dann Sozialabbau". Telepolis (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Richard Bernstein (7 February 2004), Archived 13 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine New York Times.

- Moritz Schuller (7 September 2003), The right to revise Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- Ben Knight (19 January 2016), Time to end interview authorization in Germany? Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Deutsche Welle

- PAT (28 November 2003). "Geheime Verschlusssache Interview". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). p. 1. ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- Wieduwilt, Hendrik (6 October 2021). "Die Autorisierung von Interviews: ein Machtkampf". Übermedien (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Sebastian Fischer (13 November 2007), Müntefering Resignation: Merkel Loses 'Mr. Grand Coalition' Archived 16 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Spiegel Online.

- "Wen beruft Olaf Scholz aus der rheinland-pfälzischen SPD?". swr.online (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Scholz legt Bundestagsmandat nieder". ndr.de (in German). 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013.

- Andreas Cremer and Brian Parkin, "Muentefering, Vice-Chancellor Under Merkel, Quits" Archived 25 May 2012 at archive.today, Bloomberg.com, 13 November 2007.

- "Merkel defends record as Germany's tense governing coalition hits 2-year mark", Associated Press, 21 November 2007.

- "Olaf Scholz". SPD-Bundestagsfraktion (in German). 13 September 2021. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "Bilderberg Meetings: Sitges, Spain 3–6 June 2010 – Final List of Participants". Bilderberg. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "AICGS Coverage of the 2011 Land Elections". Archived from the original on 16 March 2011.

- "Die vielen Baustellen von König Olaf". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). 15 February 2015. ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Egloff folgt auf Scholz". Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). 11 March 2011.

- "Stapelfeldt wird Hamburgs Zweite Bürgermeisterin". Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). 18 March 2011.

- Expected Attendees at Tonight's State Dinner Archived 19 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Office of the First Lady of the United States, press release of 7 June 2011.

- Josh Wingrove (17 February 2017), Trudeau Stresses Fair Wages, Tax Compliance in Warning to Europe Archived 18 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Bloomberg News.

- Scholz Bevollmächtigter für deutsch-französische Kulturzusammenarbeit Archived 12 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine Die Welt, 21 January 2015.

- Brautlecht, Nicholas (23 September 2013). "Hamburg Backs EU2 Billion Buyback of Power Grids in Plebiscite". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Donahue, Patrick; Delfs, Arne (30 September 2013). "Germany Sets Coalition Talks Date as Weeks of Bartering Loom". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Donahue, Patrick (28 October 2013). "Merkel Enters Concrete SPD Talks as Finance Post Looms". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Buergin, Rainer; Jennen, Birgit (20 September 2013). "Schaeuble Seen Keeping Finance Post Even in SPD Coalition". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Buergin, Rainer (4 March 2015). "Merkel Weighs End of Reunification Tax for East Germany". Bloomberg Business. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Copley, Caroline (15 February 2015). "Merkel's Conservatives Suffer Blow in State Vote, Eurosceptics Gain". The New York Times.

- NDR. "Olaf Scholz: Hanseat und Comeback-Spezialist". www.ndr.de (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Olaf Scholz gewählt: Rot-Grün in Hamburg startet mit Vertrauensvorschuss". www.handelsblatt.com (in German). 15 April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Hamburg mayor: our Olympics will cost $12.6bn, less than London 2012". The Guardian. 8 October 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Karolos Grohmann (29 November 2015), Hamburg drops 2024 Games bid after referendum defeat Archived 25 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- Arno Schuetze and Foo Yun Chee (27 May 2015), HSH Nordbank strikes rescue deal with EU Archived 12 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- "Cum-Ex-Skandal:"Ich kann die Entscheidung nicht nachvollziehen"". Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "Hamburg tax affair follows Olaf Scholz to Berlin". The Irish Times. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- NDR. "Nachrichten aus Hamburg". www.ndr.de. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Nienaber, Michael (29 May 2018). "Germany's 'miserly' Scholz irks comrades at home and abroad". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "SPD leadership choice threatens Germany's ruling coalition". Reuters. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Chazan, Guy (4 June 2021). "German stimulus aims to kick-start recovery 'with a ka-boom'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- Nasr, Joseph (9 May 2021). "Germany's SPD appeal to working class before election". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Holger Hansen, Thomas Leigh and Sabine Siebold (27 April 2021), Germany to spend 90% of EU recovery money on green, digital goals Archived 24 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- Nienaber, Michael; Thomas, Leigh; Halpin, Padraic (6 April 2021). "Germany and France see global tax deal, Ireland has doubts". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Nienaber, Michael (14 June 2021). "Analysis: Germany's Scholz bets on experience in uphill election battle". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Reiermann, Christian (5 June 2021). "G7-Einigung auf Mindeststeuer: Olaf Scholz ist stolz auf Einigung – aber Arbeit bleibt". Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 29 October 2021.

- "Scholz kauft Steuerdaten von anonymem Informanten". Der Spiegel. 6 November 2021. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- "Scholz kündigt Neuaufstellung der BaFin an". Bundesfinanzministerium.de. 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021.

- "EU-Behörde sieht Defizite bei Aufsicht im Wirecard-Skandal". Welt. 3 November 2020. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021.

- O'Donnell, John; Kraemer, Christian (22 April 2021). "Germany's finance minister rejects blame for Wirecard fiasco". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "German minister denies responsibility in Wirecard scandal". Associated Press. 22 April 2021. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Chazan, Guy (16 August 2020). "Wirecard casts shadow over Scholz's bid to be German chancellor". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Chazan, Guy (22 April 2021). "Olaf Scholz defends German government's record on Wirecard". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Scholz schließt im Juni noch SPD-Vorsitz aus. In: ZDF.de. 16. August 2019. (in der ARD-Sendung "Anne Will").

- "Olaf Scholz will nicht SPD-Parteivorsitzender werden". Zeit.de. 3 June 2019.

- "Wortbruch auf offener Bühne:AKK und Scholz sind Symbolfiguren einer Vertrauenskrise". Focus.de. 27 August 2019.

- "Olaf Scholz will SPD-Chef werden". Spiegel.de. 16 August 2019.

- "Olaf Scholz tritt mit Klara Geywitz an". Spiegel.de. 20 August 2019.

- "Die (Selbst-)Rettung – Olaf Scholz will nun doch SPD-Chef werden". Handelsblatt.de. 18 August 2019.

- "Scholz/Geywitz gegen Walter-Borjans/Esken in Stichwahl um SPD-Vorsitz". Spiegel.de. 26 October 2019.

- "SPD-Mitglieder stimmen für Saskia Esken und Norbert Walter-Borjans als Parteichefs". Spiegel.de. 30 November 2019.

- Erika Solomon (10 August 2020), German Social Democrats pick Olaf Scholz to run for chancellor Archived 24 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine Financial Times.

- "SPD-Spitze nominiert Olaf Scholz als Kanzlerkandidaten". Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Ende des linken Flügels". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Frederik Pleitgen, Salma Abdelaziz, Nadine Schmidt, Stephanie Halasz and Laura Smith-Spark (26 September 2021). "SPD wins most seats in Germany's landmark election, preliminary official results show". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Die Ampel kann kommen: SPD, FDP und Grüne empfehlen Koalitionsgespräche". Der Spiegel (in German). 15 October 2021. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- Apetz, Andreas (24 November 2021). "Ampel-Koalition: So sieht der Fahrplan nach dem Koalitionsvertrag aus". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Bennhold, Katrin (8 December 2021). "Germany Live Updates: Parliament Approves Scholz as Chancellor, Ending Merkel Era". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Liveblog: ++ Kabinett vereidigt – Regierungsarbeit kann starten ++". Tagesschau (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Tensions overshadow Olaf Scholz's inaugural visit to Warsaw". The Irish Times. 14 December 2021.

- "Saudi Arabia: German arms export ban set to soften?". Tactical Report. 18 March 2022.

- "German Ban on Arms Exports to Saudis Spurs Pushback". Der Spiegel. 6 March 2019.

- "Scholz secures gas deal with Abu Dhabi amid pressure on human rights". Euractiv. 26 September 2022.

- "Germany's Scholz seeks to deepen energy partnership with Saudi Arabia". Reuters. 24 September 2022.

- "German government approves arms exports to Saudi Arabia: reports". Deutsche Welle. 29 September 2022.

- "Ukraine crisis: Germany halts Nord Stream 2 approval". dw.com. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Russia should not be cut off from SWIFT at the moment - Germany's Scholz". Reuters. Reuters. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "'A new era': Germany rewrites its defence, foreign policies". France 24. AFP. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Scholz and liberal finance minister clash over nuclear phase-out". Euractiv. 9 June 2022.

- "Germany Confronts Its Nuclear Demons". Foreign Policy. 20 June 2022.

- "How Bad Will the German Recession Be?". Der Spiegel. 14 September 2022.

- "A Grave Threat to Industry in Germany". Der Spiegel. 21 September 2022.

- "Germany, EU race to fix energy crisis". Euronews. 14 September 2022.

- "Germany to mobilise €200bn economic 'shield' to field energy crisis". Euractiv. 30 September 2022.

- Brost, M., & P. Dausend: Olaf Scholz: Ich war der "Scholzomat". Archived 27 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine In: Zeit 26/2013.

- The discreet charm of the Scholzomat Archived 25 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine In: Zeit, 26 September 2021.

- Emily Schultheis (5 January 2018), 8 key players in Germany's coalition talks Archived 8 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Politico Europe.

- "China, Germany promise closer financial cooperation". Associated Press. 18 January 2019.

- "From client to competitor: China's rise prompts German rethink". Reuters. 15 January 2019.

- "The China Challenge for Olaf Scholz". Human Rights Watch. 20 May 2022.

- "Scholz Prepares First Official Trip to China as German Position Turns Hawkish". Bloomberg. 22 September 2022.

- "Germany's Scholz calls for coordinated approach to convince Turkey to end Syria operation". Reuters. 15 October 2021.

- "Angriff auf die Mittelschicht: Warum Olaf Scholz' Aktiensteuer eine schlechte Idee ist". Stern.de. 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- Eckert, Daniel (9 September 2019). "Aktiensteuer: Finanzexperten kritisieren Pläne von Olaf Scholz". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Thorsten Mumme (13 October 2019). "Olaf Scholz, der Anti-Aktionär". Der Tagesspiegel. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- "Scholz will uns Jungen die letzte Möglichkeit des Sparens nehmen". Focus Online. 23 June 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- "Medienbericht: Scholz legt offenbar Gesetzentwurf für Börsensteuer vor". Spiegel Online (in German). 9 December 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Hermann-Josef Tenhagen (14 December 2019). "Finanztransaktionssteuer: Olaf Scholz zerstört eine gute Idee". Der Spiegel (online). Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- dab/AFP (5 March 2020). "Forscher sehen gravierende Schwächen bei Finanztransaktionsteuer". Der Spiegel (online). Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- Myriam Rivet and Michael Nienaber (10 June 2018), France, Germany still split on eurozone reforms, French official says Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- ""Ein großer Wurf"". ZDF. 20 September 2019.

- "Großer Wurf?: Wissenschaftler kritisieren deutsches Klimapaket". Faz.net (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Götze, Susanne (20 September 2019). "Wissenschaftler zum Klimapaket der Bundesregierung: Gute Nacht". Spiegel Online (in German). Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Mojib Latif (26 September 2019). "Kritik an Bundesregierung – Latif: Klimapaket verdient den Namen nicht". Deutschlandfunk. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- Christian Endt. "Klimapaket: Wissenschaftler finden CO2-Preis zu niedrig". Süddeutsche Zeitung. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- "Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V.: Geheimdeal gegen das Klima". Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V. (in German). Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- "ZEIT ONLINE | Lesen Sie zeit.de mit Werbung oder im PUR-Abo. Sie haben die Wahl". www.zeit.de. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- "ZEIT ONLINE | Lesen Sie zeit.de mit Werbung oder im PUR-Abo. Sie haben die Wahl". www.zeit.de. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Stukenberg, Kurt (11 February 2021). "SPD-Engagement für Nord Stream 2: Gasimport + Gasimport = Klimaschutz". Der Spiegel (in German). ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- WELT (9 February 2021). "Scholz wollte mit Milliarden-Deal US-Sanktionen gegen Nord Stream 2 abwenden". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- "Deutschland soll bis 2045 klimaneutral sein". Heute.de. 5 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- "Scholz Vows He'll Be Chancellor by Year-End to Push Green Energy". Bloomberg. 13 October 2021.

- "Gemeinsame Ziele und Standards: Scholz will internationalen Klimaclub gründen". RND.de. 18 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- Wacket, Markus (23 November 2021). "EXCLUSIVE German parties agree on 2030 coal phase-out in coalition talks -sources". Reuters. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- "2G und Impfen: Das sind die neuen Maßnahmen" [2G and vaccination: these are the new measures]. ZDF (in German). 2 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Wegen Omikron: Bald auch strengere Corona-Regeln für Geimpfte" [Because of Omicron: Stricter corona rules soon also for vaccinated]. NDR (in German). 24 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Corona-Gipfel: Olaf Scholz will jetzt drastisch reagieren" [Corona Summit: Olaf Scholz wants to react dramatically]. T-Online (in German). 2 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Olaf Scholz für generelle Corona-Impfpflicht und 2G im Einzelhandel" [Olaf Scholz for general corona vaccinations and 2G in retail]. RND (in German). 30 November 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Nächster Corona-Hammer droht: Scholz will 2G-Pflicht beim Einkaufen" [Nearest Corona Hammer threatens: Scholz wants 2G duty when shopping]. Merkur.de (in German). 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Germany's Scholz urges compulsory COVID-19 jabs for all adults". Reuters. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Oelofse, Louis. "German Chancellor Olaf Scholz eyes COVID vaccine mandate | DW | 23 January 2022". DW.COM. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Staiano-Daniels, Lucian. "The Far-Right Has Turned East Germans Against Vaccines". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- "Germany hits back at US for placing sanctions on critical European gas pipeline". ABC News. 21 December 2019.

- "Incoming German government commits to NATO nuclear deterrent". Defense News. 24 November 2021.

- Dettmer, Jamie (7 December 2021). "Washington Hopeful of Close Relations With Germany's Scholz". Voice of America. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- Bennhold, Katrin (25 January 2022). "Where Is Germany in the Ukraine Standoff? Its Allies Wonder". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- "Why Germany isn't sending weapons to Ukraine". BBC News. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- "Russia Ukraine news Live: Street fighting begins in Kyiv". Marca. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- "New Chancellor Meets Old Resentments. Polish PM Receives Olaf Scholz in Warsaw, Talks of War Reparations and a "Europe of Sovereign States"". Gazeta Wyborcza. 13 December 2021.

- "Leaders of Poland, Germany call for 'swift' solution to Warsaw's rule of law row with EU". Politico. 13 December 2021.

- "Poland's ruling party picks a fight with Germany". The Economist. 17 August 2021.

- WELT, DIE (2 August 2017). "Zweiter Weltkrieg: Polens Regierung prüft Reparationsforderungen an Deutschland". DIE WELT. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Fact check: Does Germany send weapons to crisis regions?". Deutsche Welle. 6 February 2022.

- Von Der Burchard, Hans (26 February 2022). "Pressure mounts on Germany to drop rejection of SWIFT ban for Russia". Politico. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- "Putin Accidentally Started a Revolution in Germany". FP. 27 February 2022.

- "Experts React: What's behind Germany's stunning foreign-policy shift?". Atlantic Council. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Germany: Chancellor Scholz vows to help Ukraine in speech to parliament". DW. 23 March 2022.

- "Germany to Provide Over 1 Billion Euros' Military Aid to Ukraine". Defense News. 17 April 2022.

- Bennhold, Katrin (6 April 2022). "The End of the (Pipe)line? Germany Scrambles to Wean Itself Off Russian Gas". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Wintour, Patrick (9 April 2022). "Germany will stop importing Russian gas 'very soon', says Olaf Scholz". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "German minister heads to Qatar to seek gas alternatives". Deutsche Welle. 19 March 2022.

- "Germany Signs Energy Deal With Qatar As It Seeks To reduce Reliance On Russian Supplies". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 March 2022.

- "Germany goes on a mission to secure supplies of Qatari gas". Euractiv. 21 March 2022.

- Nienaber, Michael; Delfs, Arne (6 April 2022). "Scholz Shoots Down Appeal to Reverse Germany's Nuclear Exit". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Saxena, Astha (8 April 2022). "'Disgrace' German Chancellor slammed over delay in sending high-end tanks to Ukraine". Daily Express. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- "Olaf Scholz: Ukraine won't accept Russian dictatorship". Deutsche Welle. 8 May 2022.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Germany's Olaf Scholz expected to visit Ukraine | DW | 14 June 2022". DW.COM. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- "Macron, Scholz and Draghi arrive in Kyiv for historic visit". POLITICO. 16 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- "German chancellor rejects Kyiv visit — but his main rival is set to go". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- "German opposition leader visits Kyiv, Scholz refuses to go". AP NEWS. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Board of Governors Archived 28 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

- Board of Governors Archived 16 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine European Investment Bank (EIB).

- Board of Governors: Olaf Scholz European Stability Mechanism.

- Board of Governors Archived 29 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

- Members Archived 11 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- Board of Supervisory Directors and its Committees Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine KfW.

- Vetter, Philipp (14 June 2021). "Staatshilfe für Karstadt und Kaufhof: CDU-Wirtschaftsrat warnt vor weiterem Kredit". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- Laurin, Stefan (12 July 2011). "ECE: Stiftung lebendige Stadt – so geht Lobbyismus". Ruhrbarone (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Senate Archived 18 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Nationalstiftung.

- Members Archived 29 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES).

- Study Groups, Discussion Groups and Task Forces Archived 1 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine German Council on Foreign Relations.

- Ildiko Röd (25 June 2018), Vizekanzler ist Neu-Potsdamer Archived 21 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Märkische Allgemeine.

- Forster, Joel (22 September 2021). "Germany election: Christians not exempt from falling into polarisation". Evangelical Focus. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- "Olaf Scholz: Darum verzichtet er beim Amtseid auf "So wahr mir Gott helfe"". Der Westen (in German). 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links

Media related to Olaf Scholz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Olaf Scholz at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Olaf Scholz at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Olaf Scholz at Wikiquote- Appearances on C-SPAN