East Timor

East Timor (/ˈtiːmɔːr/ (![]() listen)), also known as Timor-Leste (/tiˈmɔːr ˈlɛʃteɪ/; Portuguese pronunciation: [ti'moɾ 'lɛʃ.tɨ]; Tetum: Timór Lorosa'e[9]), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste[10] (Portuguese: República Democrática de Timor-Leste,[11] Tetum: Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste[9]),[12] is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the Oecusse exclave on the north-western half, and the minor islands of Atauro and Jaco. Australia is the country's southern neighbour, separated by the Timor Sea. The country's size is 14,874 square kilometres (5,743 sq mi). Dili is its capital city.

listen)), also known as Timor-Leste (/tiˈmɔːr ˈlɛʃteɪ/; Portuguese pronunciation: [ti'moɾ 'lɛʃ.tɨ]; Tetum: Timór Lorosa'e[9]), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste[10] (Portuguese: República Democrática de Timor-Leste,[11] Tetum: Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste[9]),[12] is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the Oecusse exclave on the north-western half, and the minor islands of Atauro and Jaco. Australia is the country's southern neighbour, separated by the Timor Sea. The country's size is 14,874 square kilometres (5,743 sq mi). Dili is its capital city.

Democratic Republic of

| |

|---|---|

Flag

Emblem

| |

| Motto: Unidade, Acção, Progresso (Portuguese) Unidade, Asaun, Progresu (Tetum) "Unity, Action, Progress" | |

| Anthem: Pátria (Portuguese) "Fatherland" | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | Dili 8.55°S 125.56°E |

| Official languages |

|

| National languages | 15 languages

|

| Working languages | |

| Religion (2015 census)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[4] |

• President | José Ramos-Horta |

• Prime Minister | Taur Matan Ruak |

| Legislature | National Parliament |

| Independence | |

• Portuguese Timor | 1702 |

• Independence declared | 28 November 1975 |

• Annexation by Indonesia | 17 July 1976 |

• Administered by UNTAET | 25 October 1999 |

• Independence restored | 20 May 2002 |

| Area | |

• Total | 14,874 km2 (5,743 sq mi) (154th) |

• Water (%) | Negligible |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 1,340,513 (153rd) |

• 2015 census | 1,183,643[5] |

• Density | 78/km2 (202.0/sq mi) (137th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $5.315 billion |

• Per capita | $4,031[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $1.920 billion |

• Per capita | $1,456[6] |

| Gini (2014) | 28.7[7] low |

| HDI (2019) | 0.606[8] medium · 141st |

| Currency | United States dollarb (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Timor-Leste Time) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +670 |

| ISO 3166 code | TL |

| Internet TLD | .tlc |

| |

East Timor came under Portuguese influence in the sixteenth century, remaining a Portuguese colony until 1975. Internal conflict preceded a unilateral declaration of independence and an Indonesian invasion and annexation. Resistance continued throughout Indonesian rule, and in 1999 a United Nations-sponsored act of self-determination led to Indonesia relinquishing control of the territory. As Timor-Leste, it became the first new sovereign state of the 21st century on 20 May 2002.

The national government runs on a semi-presidential system, with the popularly elected President sharing power with a Prime Minister appointed by the National Parliament. Power is centralised under the national government, although many local leaders have informal influence. The country maintains a policy of international cooperation, and is a member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, an observer of the Pacific Islands Forum, and an applicant for ASEAN membership. The country remains relatively poor, with an economy that relies heavily on natural resources, especially oil, as well as on foreign aid.

The total population is over 1.1 million, and is heavily skewed towards young people due to a high fertility rate. Education has led to the increasing literacy over the past half-century, especially in the two national languages of Portuguese and Tetum. High ethnic and linguistic diversity is reflected by the 30 local dialects spoken in the country. The majority of the population is Catholic, which exists alongside strong local traditions, especially in rural areas.

Etymology

"Timor" is derived from timur, the word for "east" in Malay, thus resulting in the tautological toponym meaning "East East"; in Indonesian, Timor Timur. In Portuguese, the country is called Timor-Leste (Leste being the word for "east"); in Tetum Timór Lorosa'e (Lorosa'e can be literally translated as "where the sun rises").[13]

The official names under the Constitution are Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste in English,[14] República Democrática de Timor-Leste in Portuguese,[11] and Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste in Tetum.[12] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) official short form in is Timor-Leste (codes: TLS & TL).[15]

History

Prehistory and Classical era

Cultural remains at Jerimalai on the eastern tip of East Timor have been dated to 42,000 years ago.[16] Descendants of at least three waves of migration are believed still to live in East Timor. The first is described by anthropologists as people of the Veddo-Australoid type. Around 3000 BC, a second migration brought Melanesians. Finally, proto-Malays arrived from south China and north Indochina.[17] Timorese origin myths recount settlers sailing around the eastern end of the island before landing in the south. These people are sometimes noted as being from the Malay Peninsula or the Minangkabau highlands of Sumatra.[18] Austronesian migration to Timor may be associated with the development of agriculture on the island.[19][20]

While there is limited information about the political system of Timor during this period, the island had developed an interconnected series of polities governed by customary law. Small communities, centred around a particular sacred house, were part of wider sucos (or principalities), which were themselves part of larger kingdoms led by a liurai. Rule of these kingdoms was dyadic, with the temporal power of the liurai balanced by the spiritual power of a rai nain, who was generally associated with the primary sacred house of the kingdom. While these polities were numerous and saw shifting alliances and relations, many were stable enough that they survived from initial European documentation in the 16th century until the end of Portuguese rule.[21]: 11–15

From perhaps the 13th century, the island exported sandalwood.[21]: 267 Timor was included in Southeast Asian, Chinese, and Indian trading networks, and in the fourteenth century was an exporter of aromatic sandalwood,[22] honey, and wax. The island was recorded by the Majapahit Empire as a source of tribute.[23]: 89 It was sandalwood that attracted European explorers to the island in the early sixteenth century. Early European presence was limited to trade,[24] with the first Portuguese settlement being on the nearby island of Solor.[23]: 90

Portuguese era (1769–1975)

Early Portuguese presence on Timor was very limited, with trade being directed through Portuguese settlements on other islands. Only in the 17th century did they establish a more direct presence on the island, a consequence of being driven out of other islands by the Dutch.[21]: 267 After Solor was lost in 1613 the Portuguese moved to Flores. In 1646 the capital moved to Kupang on Timor's west, before that was lost to the Dutch in 1652. Only then did the Portuguese move to Lifau in what is now East Timor's Oecusse exclave.[23]: 90 Effective European occupation in the east of the island only began in 1769, when the city of Dili was founded.[25] A definitive border between the Dutch and Portuguese parts of the island was established by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1914, and it remains the international boundary between the successor states Indonesia and East Timor, respectively.[26]

For the Portuguese, East Timor remained little more than a neglected trading post until the late nineteenth century, with minimal investment in infrastructure and education. Even after this period when Portugal for the first time established actual control over the interior of its colony, investment remained minimal.[21]: 269, 273 Sandalwood continued to be the main export crop with coffee exports becoming significant in the mid-nineteenth century.[27]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a faltering home economy prompted the Portuguese to extract greater wealth from its colonies, which was met with East Timorese resistance.[22] The colony was seen as an economic burden during the Great Depression, and received little support or management from Portugal.[21]: 269

During World War II, first the Allies and later the Japanese occupied Dili, and the mountainous interior of the colony became the scene of a guerrilla campaign, known as the Battle of Timor. Waged by East Timorese volunteers and Allied forces against the Japanese, the struggle resulted in the deaths of between 40,000 and 70,000 East Timorese civilians.[28] The Japanese eventually drove the last of the Australian and Allied forces out.[29] However, Portuguese control was reinstated after the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II.[30]

The 1950s saw Portugal begin investment in the colony, funding education and promoting coffee exports. However, the economy did not improve substantially, and infrastructure improvements were limited.[21]: 269 Growth rates remained low, near 2%.[31] Following the 1974 Portuguese revolution, Portugal effectively abandoned its colony in Timor and civil war between East Timorese political parties broke out in 1975.

The Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin) resisted a Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) coup attempt in August 1975,[32] and unilaterally declared independence on 28 November 1975. Fearing a communist state within the Indonesian archipelago, the Indonesian military launched an invasion of East Timor in December 1975.[33] Indonesia declared East Timor its 27th province on 17 July 1976.[34] The United Nations Security Council opposed the invasion, and the territory's nominal status in the UN remained as "non-self-governing territory under Portuguese administration".[35]

Indonesian occupation (1975–1999)

The period of Indonesian occupation was marked by violence and brutality. A detailed statistical report prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor cited a minimum of 102,800 conflict-related deaths in the period between 1974 and 1999, including approximately 18,600 killings and 84,200 "excess" deaths from hunger and illness. Portuguese, Indonesian and Catholic Church data estimated 200,000 deaths.[36] Repression and restrictions counteracted improvements in infrastructure and services, meaning there was little overall improvement in living standards during this period. Economic growth mostly benefited immigrants from elsewhere in Indonesia.[21]: 271 A huge expansion of education was intended to increase Indonesian language use and internal security as much as it was for development.[37] Fretilin resisted the invasion, initially as an army holding territory until November 1978, and then as a guerrilla resistance.[38]

The 1991 Dili Massacre was a turning point for the independence cause, bringing increased international pressure on Indonesia. Following the resignation of Indonesian President Suharto,[38] the new President BJ Habibie, prompted by a letter from Australian Prime Minister John Howard, decided to have a referendum on independence.[39] A UN-sponsored agreement between Indonesia and Portugal allowed for a UN-supervised popular referendum in August 1999. A clear vote for independence was met with a punitive campaign of violence by East Timorese pro-integration militias supported by elements of the Indonesian military. In response, the Indonesian Government allowed a multinational peacekeeping force, INTERFET to restore order and aid East Timorese refugees and internally-displaced persons.[40] On 25 October 1999, the administration of East Timor was taken over by the UN through the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET).[41][42] The INTERFET deployment ended in February 2000 with the transfer of military command to the UN.[43]

Contemporary era

On 30 August 2001, the East Timorese voted in their first election organised by the UN to elect members of the Constituent Assembly.[14][44] On 22 March 2002, the Constituent Assembly approved the Constitution.[14] By May 2002, more than 205,000 refugees had returned.[45] On 20 May 2002, the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of East Timor came into force and East Timor was recognised as independent by the UN.[44][46] The Constituent Assembly was renamed the National Parliament, and Xanana Gusmão was elected as the country's first president.[47] On 27 September 2002 the country became a member state by the UN.[48]

In 2006, the United Nations sent in security forces to restore order when unrest and factional fighting forced 155,000 people to flee their homes.[49][50] The following year, Gusmão declined to run for another term. While there was minor incidents in the build-up to the mid-year presidential elections, the process was peaceful overall and José Ramos-Horta was elected president.[51][52] In June 2007, Gusmão ran in the parliamentary elections and became prime minister. In February 2008, Ramos-Horta was critically injured in an attempted assassination. Prime Minister Gusmão also faced gunfire separately but escaped unharmed. Australian reinforcements were immediately sent to help keep order.[53] In March 2011, the UN handed over operational control of the police force to the East Timor authorities. The United Nations ended its peacekeeping mission on 31 December 2012.[49]

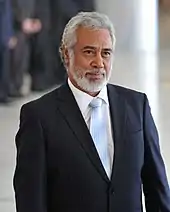

Francisco Guterres of the centre-left Fretilin party became president in May 2017.[54] The main party of the AMP coalition, the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction, led by independence hero Xanana Gusmão, was in power from 2007 to 2017, but the leader of Fretilin, Mari Alkatiri, formed a coalition government after the July 2017 parliamentary election. However, the new minority government soon fell, leading to a second general election in May 2018.[55] In June 2018, former president and independence fighter, Jose Maria de Vasconcelos, known as Taur Matan Ruak, of the three-party coalition, Alliance of Change for Progress (AMP), became the new prime minister.[56] José Ramos-Horta of the centre-left CNRT has served as the president of East Timor since 20 May 2022 after winning the April 2022 presidential election runoff against the incumbent president, Francisco Guterres .[57]

Politics and government

The political system of East Timor is semi-presidential, based upon the Portuguese system.[58][59]: 175 In addition to the separation of executive powers between the president and the prime minister, the separation of powers between the executive, legislature, and judiciary is enshrined in the constitution.[60]: 12 Individuals are not allowed to participate in both the legislature and the executive. While the legislature is intended to provide a check on the executive, in practice the executive has maintained control of the legislature, under all political parties.[59]: 174 The executive, through the council of ministers, also holds some formal legislative powers.[59]: 175 The judiciary operates independently, although there are instances of executive interference.[60]: 13, 39 [61] Access to courts remain a challenge, with some mobile courts being developed to counter this.[61] Despite political rhetoric, the constitution and democratic institutions are almost universally respected.[60]: 15, 42 Elections are run by an independent body,[62]: 216 and turnout is high. The political system has wide public acceptance.[60]: 17 [63]: 106

Formally, the directly elected president holds relatively limited powers compared to those in similar systems, with no power over the appointment and dismissal of the prime minister and the council of ministers. However, given they are directly elected, past presidents have wielded great informal power and influence.[59]: 175 The prime minister is chosen by parliament. If the president vetoes a legislative action, parliament can overturn the veto with a two-thirds majority.[60]: 10

The head of state of East Timor is the president of the republic, who is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. Although the president's executive powers are somewhat limited, they do have the power to veto government legislation, initiate referendums, and to dissolve parliament in the event that it is unable to form a government or pass a budget.[4]: 244 Following elections, the president usually appoints the leader of the majority party or coalition as prime minister of East Timor and the cabinet on the proposal of the latter. As head of government, the prime minister presides over the cabinet.[64] The president is limited to two terms.[61]

.jpg.webp)

Representatives in the unicameral National Parliament are elected by popular vote to a five-year term.[61] The number of seats can vary from a minimum of fifty-two to a maximum of sixty-five. Parties must achieve 3% of the vote to enter parliament, with seats for qualifying parties allocated using the D'Hondt method.[64] Elections occur within the framework of a competitive multi-party system. Upon independence, power was held by the Fretilin political party, which was formed shortly before the Indonesian invasion and led its resistance. Given its history, Fretilin viewed itself as the natural party of government, and supported a multi-party system under the expectation that a dominant-party system would develop. Support from the United Nations and the international community, both before and after independence, allowed the nascent political system to survive shocks such as the 2006 East Timorese crisis.[59]: 173

For parliamentary elections all candidates run in a single national district in a party-list system. One in three of all candidates presented by political parties must be women. This system promotes a diversity of political parties, but gives voters little influence over the individual candidates selected by each party.[59]: 175–176 Political parties or political coalitions must receive at least 4% of the total votes to enter parliament.[60]: 10 The National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction became the main opposition party beginning with its establishment and then victory in the 2007 parliamentary elections.[59]: 168–169 While both major parties have been relatively stable, they remain led by an "old guard" of individuals who came to prominence during the resistance against Indonesia.[59]: 175 [60]: 10–11 [65][66] Most parties are based on personality, rather than policy.[60]: 16 While women hold more than a third of parliamentary seats due to the legislation requiring female candidates, they are less prominent at other levels and within party leadership.[61]

An active civil society functions independently of the government, as do media outlets.[60]: 11–12 Civil society organisations are concentrated in the capital, including student groups. Due to the structure of the economy, there are no powerful trade unions.[60]: 17 The Catholic Church has strong influence in the country.[60]: 40 The National Police of East Timor and Timor Leste Defence Force have held a monopoly on violence since 2008, with very few guns present outside of these organisations.[60]: 8 While there are allegations of abuse of power, there is some judicial oversight of police and public trust in the institution has grown.[61]

Political divisions exist along class lines and along geographical lines. There is broadly a divide between Eastern and Western areas of the country, stemming from differences that arose under Indonesian rule. Fretilin in particular is strongly linked to the Eastern areas.[59]: 176–177 Politics and administration is centred in the capital Dili, with the national government responsible for most civil services.[60]: 9, 36 Oecusse, separated from the rest of the country by Indonesian territory, is a Special Administrative Region with some autonomy.[59]: 180

Administrative divisions

East Timor is divided into fourteen municipalities, which in turn are subdivided into 64 administrative posts, 442 sucos (villages), and 2,225 aldeias (hamlets).[67][68][69]

- Aileu

- Ainaro

- Atauro

- Baucau

- Bobonaro

- Cova Lima

- Dili

- Ermera

- Lautém

- Liquiçá

- Manatuto

- Manufahi

- Oecusse

- Viqueque

The existing system of municipalities and administrative posts was established during Portuguese rule.[70]: 3 While decentralisation is mentioned in the constitution, administrative powers generally remain with the national government operating out of Dili.[71]: 2 Upon independence there was debate about how to implement decentralisation, with multiple models proposed which would create different levels of administration between the sucos and the central government. In most proposals, there were no specific provisions for suco level governance, and they were expected to continue to operate as mostly customary units. In the end, the existing districts were kept and renamed municipalities in 2009, and received very few powers.[63]: 88–92 Each municipality is led by a civil servant appointed by the central government, a structure that was only put in place in 2016.[70]: 4, 7 The isolated Oecusse municipality, which has a strong identity and is fully surrounded by Indonesian territory, is specified by Articles 5 and 71 of the 2002 constitution to be governed by a special administrative policy and economic regime. Law 3/2014 of 18 June 2014 was created to implement this constitutional provision, which went into effect in January 2015 turning Oecusse into a Special Administrative Region. The region began operating its own civil service in June 2015.[72][73] In January 2022 the island of Atauro, formerly an Administrative Post of Dili, became its own municipality.[69]

Administration in the lowest levels of the administrative system of East Timor, the aldeias and sucos, generally reflects traditional customs,[71]: 1 reflecting community identity and relationships between local households.[74]: 4 Sucos generally contain 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants. Their long persistence and links to local governance means the sucos are the level of government that is linked to community identities, rather than any high level of administration.[63]: 89 Such relationships are associated specifically with the kinship groups within that land however, rather than the land itself.[75]: 52–53 Relationships between sucos also reflect customary practices, for example through the reciprocal exchanging of support for local initiatives.[74]: 9 Laws passed in 2004 provided for the election of some suco officials, but assigned these positions no formal powers. An updated law in 2009 established the expected mandate of these positions, although it continue to leave them outside of the formal state system, reliant on municipal governments to provide formal administration and services.[63]: 94–97 Further clarification was given in 2016, which entrenched the treatment of sucos and aldeias more as communities than formal levels of administration. Despite this lack of formal association with the state, suco leaders hold great influence and are often seen by their community as representatives of the state, and they have responsibilities usually associated with civic administration.[70]: 7–10

Foreign relations and military

International cooperation has always been important to East Timor, with donor funds making up 80% of the budget before oil revenues began to replace them.[60]: 42–44 International forces also provided security, with five UN missions being sent to the country from 1999. The final one, the United Nations Integrated Mission in East Timor, began after the 2006 East Timorese crisis and concluded in 2012.[76]: 4, 14

East Timor is a long-standing applicant to join ASEAN,[60]: 42–44 having formally applied in 2011.[77] Despite a closer cultural affinity to Pacific nations, the country has targeted ASEAN membership since before its independence for both economic and security purposes, something which was seen as mutually exclusive with membership in Pacific bodies. ASEAN membership was sought to improve the relationship with Indonesia, although it has stalled due to a lack of support from some ASEAN states.[76]: 10–11 East Timor is thus an observer to the Pacific Islands Forum and the Melanesian Spearhead Group. More broadly, the country is a leader within the Group of Seven Plus (g7+), an organisation of fragile states. It is also a member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.[60]: 42–44 [78]

Continuing bilateral donors include Australia, Portugal, Germany, and Japan, and the country has a reputation for effectively and transparently using donor funds. Good relations with Australia and with Indonesia are a policy goal for the government, despite historical and more recent tensions. These countries are important economic partners, and provide most transport links to the country.[60]: 42–44 China has also increased its presence as a donor, contributing to infrastructure in Dili.[76]: 12

The relationship with Australia was dominated from before independence by disputes over natural resources in the Timor Gap which lies between them, which hampered the establishment of a mutually agreed border. The dominance of Australian hard power led East Timor to utilise public diplomacy and forums for international law to push their case.[79][80] The dispute was resolved in 2018 following negotiations at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, when a maritime boundary between the two was established along with an agreement on natural resource revenues.[81][82]

The Timor Leste Defence Force (F-FDTL) was established in 2001, replacing Falintil, and was restructured following the events of 2006. It is responsible not only for safeguarding against external threats, but also for tackling violent crime, a role in which it overlaps with the National Police of East Timor. The size of these forces remains small, with 2,200 soldiers in the regular army and 80 in a naval component. A single aircraft and seven patrol boats are operated, with plans to expand the naval component. There is some military cooperation with Australia, Portugal, and the United States.[83]

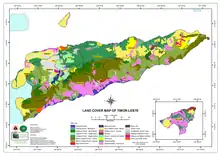

Geography

Located in between Southeast Asia and the South Pacific,[84]: 2 the island of Timor is the largest of the Lesser Sunda Islands, which lie within the Malay archipelago.[85]: 1 The island is surrounded by the Ombai and Wetar Straits of the rougher Banda Sea in the north, and the calmer Timor Sea in the south.[84]: 2 [86] East Timor shares the island with Indonesia, which separates the main part of the country from the Oecusse exclave. The island of Atauro lies north of the mainland,[84]: 2 with the fourth area being the small island of Jaco. The Savu Sea lies north of Oecusse.[87]: 1 The country is about 265 kilometres (165 mi) long and 97 kilometres (60 mi) wide, with a total land area of 14,874 square kilometres (5,743 sq mi).[85]: 1 This territory is situated between 8′15S – 10′30S latitude and 125′50E – 127′30E longitude.[88]: 2 The country's coastline covers around 700 kilometres (430 mi),[85]: 27 while the main land border with Indonesia is 125 kilometres (78 mi) long, and the Oecusse land border is around 100 kilometres (62 mi) long.[87]: 1 Maritime borders exist with Australia to the south and Indonesia elsewhere.[89][90] East Timor has an exclusive economic zone of 77,051 km2 (29,750 sq mi).[91]

The interior of the country is mountainous,[84]: 2 with ridges of inactive volcanic mountains extending along the island.[21]: 2 Almost half of the country has a slope of at least 40%. The south is slightly less mountainous, and has some plains near the coastline.[88]: 2 The highest point is Tatamailau (also known as Mount Ramelau) at 2,963 metres (9,721 ft).[86][92] Most rivers dry up at least partially during the dry season.[87]: 2 Outside of some coastal areas and river valleys, the soil is shallow and prone to erosion, and its quality is poor.[88]: 13 [21]: 2 The capital, largest city, and main port is Dili, and the second-largest city is the eastern town of Baucau.

The climate is tropical with relatively stable temperatures throughout the year. A wet season lasts from December to May throughout the country, and lasts slightly longer in the south[88]: 5 and the interior due to the effect of a monsoon from Australia.[21]: 2 During this period, rainfall can reach 222–252 millimetres (8.7–9.9 in) per month. In the dry season, it drops to 12–18 millimetres (0.47–0.71 in).[88]: 5 The country is vulnerable to flooding and landslides that occur as a result of heavy rain, especially when rainfall levels are increased by the La Niña effect.[88]: 13 The mountainous interior is cooler than the coasts.[86] Coastal areas are heavily dependent on groundwater, which faces pressure from mismanagement, deforestation, and climate change.[88]: 14 While the temperature is thought to have experienced a small increase due to climate change, there has been little change in rainfall patterns.[88]: 6

Coastal ecosystems around the country are diverse and varied, with vary spatially between the north and south coastlines, as well as between the eastern tip and areas more to the west. These ecosystems include coral reefs, as the country's waters are part of the Coral Triangle biodiversity hotspot.[85]: 28 The easternmost area of East Timor consists of the Paitchau Range and the Lake Ira Lalaro area, which contains the country's first conservation area, the Nino Konis Santana National Park.[93] It contains the last remaining tropical dry forested area within the country. It hosts a number of unique plant and animal species and is sparsely populated.[94] The northern coast is characterised by a number of coral reef systems that have been determined to be at risk.[95]

There are around 41,000 terrestrial plant species in the country, with around 35% of the land being forested in the mid 2010s.[96]: 1 The forests of the northern coast, central uplands, and southern coast are distinct.[87]: 2 East Timor is home to the Timor and Wetar deciduous forests ecoregion.[97] There is some environmental protection in law, but it has not been a government priority.[60]: 27 [85]: 10–14 In addition to climate change, local ecosystems are threatened by deforestation, land degradation, overfishing, and pollution.[96]: 2–3

Economy

(previous_and_data).png.webp)

The economy of East Timor is a market economy, which used to depend upon exports of a few commodities such as coffee, marble, petroleum, and sandalwood.[98] Internally, market operations are limited by widespread poverty.[60]: 20 The country uses the United States dollar. The economy is generally open to foreign investment, although a prohibition on foreigners owning land means many require a local partner in the country.[60]: 20 Competition is limited by the small size of the economy, rather than any government barriers. There are far more imports than exports,[60]: 21 and prices for goods are often higher than in nearby countries.[60]: 27 Inflation is strongly affected by government spending.[99]: 257 Growth has been slow, averaging just 2.5% per year from 2011 to 2021.[100]: 24

Most of the country is very poor, with just more than 40% living under the national poverty line. This poverty is especially prevalent in rural areas, where many are subsistence farmers or fishermen. Even in urban areas, the majority are poor. Overall, women are poorer than men, often being employed in lower-paying careers.[60]: 18 Malnutrition is common, with over half of children showing stunted growth.[99]: 255 While 91% of married working age (15-49) men were employed as of 2016, only 43% of married working age women were. There are small disparities in favour of men in terms of home and land ownership and owning a bank account.[101]: 14 The eastern three municipalities, which contain around a quarter of the population, has less poverty than the western areas, which contain 50% of the popuation.[62]: 214

94% of domestic fish catch comes from the ocean, especially coastal fisheries.[88]: 17 66% of families are in part supported by subsistence activities, however the country as a whole does not produce enough food to be self-sustaining, and thus relies on imports.[88]: 16 Agricultural work carries the implication of poverty, and the sector receives little investment from the government.[99]: 260 Those in the capital of Dili are on average better off, although they remain poor by international standards.[99]: 257 The small size of the private sector means the government is often the customer of public businesses. A quarter of the national population works in the informal economy, with the official public and private sectors employing 9% each.[60]: 18 Of those of working age, around 23% are in the cash economy, 21% are students, and 27% are subsistence farmers and fishers.[60]: 21 The economy is mostly cash-based, with little commercial credit available from banks.[100]: 11–12 Remittances from overseas workers add up to around $100 million annually.[99]: 257

This poverty belies significant wealth in terms of natural resources, which at the time of independence had per capita value equivalent to the wealth of an upper-middle income country. Over half of this was in oil, and over a quarter natural gas. The Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund was established in 2005 to turn these non-renewable resources into a more sustainable form of wealth.[85]: 4–6 From 2005 to 2021, $23 billion earned from oil sales has entered the fund. $8 billion has been generated from investments, while $12 billion has been spent.[60]: 30 A decrease in oil and gas reserves led to decreasing HDI beginning in 2010.[60]: 18–19 80% of government spending comes from this fund, which as of 2021 had $19 billion, 10 times greater than the size of the national budget. As oil income has decreased, the fund is at risk of being exhausted. Withdrawals have exceeded sustainable levels almost every year since 2009.[60]: 23 Resources within the Bayu-Undan field are expected to soon run out, while extracting those within the so far undeveloped Greater Sunrise field has proven technically and politically challenging. Remaining potential reserves are also losing value as oil and gas become less favoured sources of energy.[99]: 264–272 [102]

The country's economy is dependent on government spending and, to a lesser extent, assistance from foreign donors.[103] Government spending decreased beginning in 2012, which had knock-on effects in the private sector over the following years. The government and its state-owned oil company often invest in large private projects. Decreasing government spending was matched with a decrease in GDP growth.[60]: 18 After the petroleum fund, the second largest source of government income is taxes. Tax revenue is less than 8% of GDP, lower than many other countries in the region and with similarly sized economies. Other government income comes from 23 "autonomous agencies", which include port authorities, infrastructure companies, and the National University of East Timor.[100]: 13, 28–309 Overall, government spending remains among the highest in the world,[100]: 12 although investment into education, health, and water infrastructure is negligible.[99]: 260

.svg.png.webp)

Private sector development has lagged due to human capital shortages, infrastructure weakness, an incomplete legal system, and an inefficient regulatory environment.[103] Property rights remain ill-defined, with conflicting titles from Portuguese and Indonesian rule, as well as needing to accommodate traditional customary rights.[60]: 23 As of 2010, 87.7% of urban (321,043 people) and 18.9% of rural (821,459 people) households have electricity, for an overall average of 38.2%.[104] The private sector shrank between 2014 and 2018, despite a growing working age population. Agriculture and manufacturing are less productive per capita than at independence.[99]: 255–256 Non-oil economic sectors have failed to develop,[105] and growth in construction and administration is dependent on oil revenue.[99]: 256 The dependence on oil shows some aspects of a resource curse.[106] Coffee made up 90% of all non-fossil fuel exports from 2013-2019, with all such exports totaling to around US$20 million annually.[99]: 257 In 2017, the country was visited by 75,000 tourists.[107]

Demographics

East Timor recorded a population of 1,183,643 in its 2015 census.[5] The population lives mainly along the coastline, where all urban areas are located.[85]: 27 Those in urban areas generally have more formal education, employment prospects, and healthcare. While a strong gender disparity exists throughout the country, it is less severe in the urban capital. The wealthy minority often go abroad for health and education purposes.[60]: 25 The population is young, with the median age being under 20.[60]: 29 In particular, a large proportion of the population (almost 45% in 2015) are males between the ages of 15 and 24, the third largest male 'youth bulge' in the world.[62]: 212

The CIA's World Factbook lists the English-language demonym for East Timor as Timorese,[108] as does the Government of Timor-Leste's website.[109] Other reference sources list it as East Timorese.[110][111] The word Maubere formerly used by the Portuguese to refer to native East Timorese and often employed as synonymous with the illiterate and uneducated, was adopted by Fretilin as a term of pride.[112]

Healthcare received 6% of the national budget in 2021.[60]: 24 From 1990 to 2019 life expectancy rose from 48.5 to 69.5. Expected years of schooling rose from 9.8 to 12.4 between 2000 and 2010, while mean years of schooling rose from 2.8 to 4.4. Progress since 2010 for these has been limited. Gross national income per capita similarly peaked in 2010, and has decreased since.[113]: 3 As of 2016, 45.8% of East Timorese were impoverished, 16.3% severely so.[113]: 6 The fertility rate, which at the time of independence was the highest in the world at 7.8,[114] dropped to 4.2 by 2016. It is relatively higher in rural areas, and among poorer[101]: 3 and less literate households.[115] As of 2016, the average household size was 5.3, with 41% of people aged under 15, and 18% of households headed by women.[101]: 2 Infant mortality stood at 30 per 1,000, down from 60 per 1,000 in 2003.[101]: 7 46% of children under 5 showed stunted growth, down from 58% in 2010. Working age adult obesity increased from 5% to 10% during the same time period. As of 2016 40% of children, 23% of women, and 13% of men had anemia.[101]: 11

| Rank | Name | Municipalities | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dili .jpg.webp) Baucau |

1 | Dili | Dili | 244,584 | |||||

| 2 | Baucau | Baucau | 17,357 | ||||||

| 3 | Maliana | Bobonaro | 12,787 | ||||||

| 4 | Lospalos | Lautém | 12,471 | ||||||

| 5 | Pante Macassar | Oecusse | 12,421 | ||||||

| 6 | Suai | Cova Lima | 9,130 | ||||||

| 7 | Ermera | Ermera | 8,045 | ||||||

| 8 | Same | Manufahi | 7,332 | ||||||

| 9 | Viqueque | Viqueque | 6,530 | ||||||

| 10 | Ainaro | Ainaro | 6,250 | ||||||

Ethnicity and language

Ethnic background and linguistic group do not clearly define Timorese communities, with many communities within these broad groupings and many areas with overlaps and hybridisation between ethnic and linguistic groups.[75]: 44 Familial relations and descent, which are interlinked with sacred house affiliation, are a more important indicator of identity.[75]: 47 Each family group generally identifies with a single language or dialect.[75]: 49 With this immense local variation in mind, there is a broad cultural and identity distinction between the east (Bacau, Lautém, and Viqueque Municipalities) and the west of the country, a product of history more than it is of linguistic and ethnic differences,[75]: 45–47 although it is very loosely associated with the two language groups.[116]: 142–143 There is a small mestiço population of mixed Portuguese and local descent.[117] There is a small Chinese minority, most of whom are Hakka.[118][119] Many Chinese left in the mid-1970s, but a significant number have also returned to East Timor following the end of Indonesian occupation.[120] East Timor has a small community of Timorese Indian, specifically Goan descent,[121] as well as historical immigration from Africa and Yemen.[117]

Likely reflecting the mixed origins of the different ethnolinguistic groups of the island, the indigenous languages fall into two language families: Austronesian and Papuan.[21]: 10 Depending on how they are classified, there are up to 19 indigenous languages with up to 30 dialects.[116]: 136 Aside from Tetum, Ethnologue lists the following indigenous languages: Adabe, Baikeno, Bunak, Fataluku, Galoli, Habun, Idaté, Kairui-Midiki, Kemak, Lakalei, Makasae, Makuv'a, Mambae, Nauete, Tukudede, and Waima'a.[122] According to the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are six endangered languages in East Timor: Adabe, Habu, Kairui-Midiki, Maku'a, Naueti, and Waima'a.[123] The largest Malayo-Polynesian group is the Tetum,[124] mostly around Dili or the western border. Other Malayo-Polynesian languages with native speakers of more than 40,000 are Mambai in the central mountains south of Dili, Baikeno in Oecusse, Kemak in the north-west interior, and Tokodede on the northwest coast.[125][126] The main Papuan languages spoken are Bunak in the centre of Timor, especially within Bobonaro Municipality; Makasae in the eastern Baucau and Viqueque municipalities; and Fataluku in the eastern Lautém Municipality.[75]: 43 The 2015 census found that the most commonly spoken mother tongues were Tetum Prasa (mother tongue for 30.6% of the population), Mambai (16.6%), Makasai (10.5%), Tetum Terik (6.05%), Baikenu (5.87%), Kemak (5.85%), Bunak (5.48%), Tokodede (3.97%), and Fataluku (3.52%). Other indigenous languages accounted for 10.47%, while 1.09% of the population spoke foreign languages natively.[127]

East Timor's two official languages are Portuguese and Tetum. In addition, English and Indonesian are designated by the constitution as "working languages".[84]: 3 [128] This is within the Final and Transitional Provisions, which do not set a final date. In 2012, 35% could speak, read, and write Portuguese, which is up significantly from less than 5% in the 2006 UN Development Report. Portuguese is recovering as it has now been made the main official language of Timor, and is being taught in most schools.[128][129] The use of Portuguese for government information and in the court system provides some barriers to access for those who do not speak it.[61] Tetum is also not understood by everyone in the country.[21]: 11 According to the Observatory of the Portuguese Language, the East Timorese literacy rate was 77.8% in Tetum, 55.6% in Indonesian, and 39.3% in Portuguese, and that the primary literacy rate increased from 73% in 2009 to 83% in 2012.[130] According to the 2015 census, 50% of the population between the ages of 14 and 24 can speak and understand Portuguese.[131] The 2015 census found around 15% of those over the age of five were literate in English.[132]

Education

East Timor's adult literacy rate in 2010 was 58.3%, up from 37.6% in 2001.[133] At the end of Portuguese rule, literacy was at 5%.[134] By 2021 it was 68% among adults, and 84% among those aged 15–24, being slightly higher among women than men.[60]: 27 More girls than boys attend school, although some drop out upon reaching puberty.[60]: 25 As of 2016 22% of working age women (15-49) and 19% of working age men had no education, 15% of women and 18% of men had some primary education, 52% of women and 51% of men had some secondary education, and 11% of women and 12% of men had higher education. Overall, 75% of women and 82% of men were literate.[101]: 2 Primary schools exist throughout the country, although the quality of materials and teaching is often poor. Secondary schools are generally limited to municipal capitals. Education takes up 10% of the national budget.[60]: 27 The country's main university is the National University of East Timor. There are also four colleges.[135]

Since independence, both Indonesian and Tetum have lost ground as media of instruction, while Portuguese has increased: in 2001 only 8.4% of primary school and 6.8% of secondary school students attended a Portuguese-medium school; by 2005 this had increased to 81.6% for primary and 46.3% for secondary schools.[136] Indonesian formerly played a considerable role in education, being used by 73.7% of all secondary school students as a medium of instruction, but by 2005 Portuguese was used by most schools in Baucau, Manatuto, as well as the capital district.[136] Portugal provides support to about 3% of the public schools in East Timor, focused on those in urban areas, further encouraging the use of the Portuguese language.[60]: 28

Religion

While the Constitution of East Timor enshrines the principles of freedom of religion and separation of church and state, Section 45 Comma 1 also acknowledges "the participation of the Catholic Church in the process of national liberation" in its preamble.[137] Upon independence, the country joined the Philippines to become the only two predominantly Roman Catholic states in Asia, although nearby parts of eastern Indonesia such as Flores and parts of Western New Guinea also have Roman Catholic majorities.[138][139]

According to the 2015 census, 97.57% of the population is Catholic; 1.96% Protestant; 0.24% Muslim; 0.08% Traditional; 0.05% Buddhist; 0.02% Hindu, and 0.08% other religions.[1] A 2016 survey conducted by the Demographic and Health Survey programme showed that Catholics made up 98.3% of the population, Protestants 1.2%, and Muslims 0.3%.[140]

The number of churches grew from 100 in 1974 to more than 800 in 1994,[135] with Church membership having grown considerably under Indonesian rule as Pancasila, Indonesia's state ideology, requires all citizens to believe in one God and does not recognise traditional beliefs. East Timorese animist belief systems did not fit with Indonesia's constitutional monotheism, resulting in mass conversions to Christianity. Portuguese clergy were replaced with Indonesian priests and Latin and Portuguese mass was replaced by Indonesian mass.[141] While just 20% of East Timorese called themselves Catholics at the time of the 1975 invasion, the figure surged to reach 95% by the end of the first decade after the invasion.[141][142] The Roman Catholic Church divides East Timor into three dioceses: the Archdiocese of Díli, the Diocese of Baucau, and the Diocese of Maliana.[143] In rural areas, Roman Catholicism is syncretised with local animist beliefs.[144] The number of Protestants and Muslims declined significantly after September 1999, as these groups were disproportionately represented among supporters of integration with Indonesia. Fewer than half of previous Protestant congregations existed after September 1999, and many Protestants were among those who remained in West Timor.[145]

Culture

The many cultures within East Timor stem from the several waves of Austronesian and Melanesian migration that led to the current population, with unique identities and traditions developing within each petty kingdom. Portuguese authorities built upon traditional structures, blending Portuguese influence into the existing political and social systems.[23]: 91–92 The presence of the Catholic Church created a point of commonality across the various ethnic groups, despite full conversion remaining limited. The Portuguese language also provided common linkages, even if direct Portuguese impact was limited.[23]: 97–98 Under Indonesian rule, resistance strengthened cultural links to Catholicism and Portuguese. At the same time, Indonesian cultural influence was spread through schools and administration.[23]: 98–99

The preservation of traditional beliefs in the face of Indonesian attempts to suppress them became linked to the creation of the country's national identity.[84]: 7–13 This national identity only began to emerge at the very end of Portuguese rule and during Indonesian rule.[116]: 134–136 A civic identity begun to develop, most clearly expressed through enthusiasm for national-level democracy,[116]: 155–156 and reflected in politics through a shift from resistance narratives to development ones.[146]: 3 The capital has developed a more cosmopolitan culture, while rural areas maintain stronger traditional practices.[60]: 30 Internal migration into urban areas, especially Dili, creates cultural links between these areas and rural hinterlands. Those in urban areas often continue to identify with a specific rural area, even those with multiple generations born in Dili.[75]: 53–54

The presence of so many ethnic and linguistic groups means cultural practices vary across the country.[84]: 11 These practices reflect historical social structures and practices, where political leaders were regarded as having spiritual powers. Ancestry was an important component of leadership, with ancestors being an important part of cultural practices. Leaders often had influence over land-use, and these leaders continue to play an informal role in land disputes and other aspects of community practice today. An important traditional concept is lulik, or sacredness. Some lulik ceremonies continue to reflect animist beliefs, for example through divination ceremonies which vary throughout the country. Sacred status can also be associated with objects, such as Portuguese flags which have been passed down within families.[84]: 7–13

Community life is centred around sacred houses (Uma Lulik), physical structures which serve as a representative symbol and identifier for each community.[75]: 47–49 The architectural style of these houses varies between different parts of the country, although following widespread destruction by Indonesian forces many were rebuilt with cheap modern materials.[147]: 22–25 The house as a concept extends beyond the physical object to the surrounding community.[23]: 92–93, 96 Kinship systems exist within and between houses. Traditional leaders, who stem from historically important families, retain key roles in administering justice and resolving disputes through methods that vary between communities.[75]: 47–49 Such leaders are often elected to official leadership positions, joining cultural and historical status with modern political status.[75]: 52 The concept of being part of a communal house has been extended to the nation, with Parliament serving as the national sacred house.[23]: 96

Art styles vary throughout the various ethnolinguistic groups of the island. Nonetheless, similar artistic motifs are present throughout, such as large animals and particular geometric patterns. Some art is traditionally associated with particular genders.[148] For example, the Tais textiles that play a widespread role in traditional life throughout the island are traditionally handwoven by women.[149] Different tais patterns are associated with different communities and more broadly linguistic groups.[116]: 137 Many buildings within central Dili maintain historical Portuguese architecture.[150]: I-5

Traditional rituals retain important, often mixed in with more modern aspects.[116]: 137 A strong oral history is highlighted in individuals able to recite long stories or poetry.[151] This history, or Lia nain, passed down traditional knowledge.[147]: 16 There remains a strong tradition of poetry.[152] Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, for example, is a distinguished poet, earning the moniker "poet warrior".[153]

See also

- Outline of East Timor

- Index of East Timor-related articles

- List of topics on the Portuguese Empire in the East

References

- "Nationality, Citizenship, and Religion". Government of Timor-Leste. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Hicks, David (15 September 2014). Rhetoric and the Decolonization and Recolonization of East Timor. Routledge. ISBN 9781317695356 – via Google Books.

- Adelman, Howard (28 June 2011). No Return, No Refuge: Rites and Rights in Minority Repatriation. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231526906 – via Google Books.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (2003). "Timor-Leste: Divided Leadership in a Semi-Presidential System". Asian Survey. 43 (2): 231–252. doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.2.231.

The semi-presidential system in the new state of Timor-Leste has institutionalized a political struggle between the president, Xanana Gusmão, and the prime minister, Mari Alkatiri. This has polarized political alliances and threatens the viability of the new state. This paper explains the ideological divisions and the history of rivalry between these two key political actors. The adoption of Marxism by Fretilin in 1977 led to Gusmão's repudiation of the party in the 1980s and his decision to remove Falintil, the guerrilla movement, from Fretilin control. The power struggle between the two leaders is then examined in the transition to independence. This includes an account of the politicization of the defense and police forces and attempts by Minister of Internal Administration Rogério Lobato to use disaffected Falintil veterans as a counterforce to the Gusmão loyalists in the army. The December 4, 2002, Dili riots are explained in the context of this political struggle.

- "Population by Age & Sex". Government of Timor-Leste. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "tetun.org". tetun.org.

- "UNGEGN list of country names" (PDF). United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names. 2–6 May 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Constituição da República Democrática de Timor" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Konstituisaun Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- Amy Ochoa Carson (2007). "East Timor's Land Tenure Problems: A Consideration of Land Reform Programs in South Africa and Zimbabwe" (PDF). Indiana International & Comparative Law Review. 17 (2): 395. doi:10.18060/17554.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "TL". ISO. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Marwick, Ben; Clarkson, Chris; O'Connor, Sue; Collins, Sophie (2016). "Early Modern Human Lithic Technology from Jerimalai, East Timor". Journal of Human Evolution (Submitted manuscript). 101: 45–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004. PMID 27886810.

- "Lesson 1 (First Part): Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia". University of Coimbra. Archived from the original on 2 February 1999.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 378. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- O’Connor, Sue (2015). "Rethinking the Neolithic in Island Southeast Asia, with Particular Reference to the Archaeology of Timor‑Leste and Sulawesi". Archipel. 90. doi:10.4000/archipel.362. S2CID 204467392.

- Donohue, Mark; Denham, Tim (April 2010). "Farming and Language in Island Southeast Asia Reframing Austronesian History". Current Anthropology. 51 (2): 223–256. doi:10.1086/650991. S2CID 4815693.

- Lundahl, Mats; Sjöholm, Fredrik (17 July 2019). The Creation of the East Timorese Economy: Volume 1: History of a Colony. Springer. ISBN 9783030194666.

- Schwarz, A. (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Westview Press. p. 198-199. ISBN 978-1-86373-635-0.

- Paulino, Vincente (2011). "Remembering the Portuguese Presence in Timor and its Contribution to the Making of Timor's National and Cultural Identity". In Jarnagin, Laura (ed.). Culture and Identity in the Luso-Asian World. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814345507.

- Leibo, Steven (2012), East and Southeast Asia 2012 (45 ed.), Lanham, MD: Stryker Post, pp. 161–165, ISBN 978-1-6104-8885-3

- "The Portuguese Colonization and the Problem of East Timorese Nationalism". Archived from the original on 23 November 2006.

- Deeley, Neil (2001). The International Boundaries of East Timor. p. 8.

- Villiers, John (July 1994). "The Vanishing Sandalwood of Portuguese Timor". Itinerario. 18 (2): 89–93. doi:10.1017/S0165115300022518. S2CID 162012899.

- "Department of Defence (Australia), 2002, "A Short History of East Timor"". Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Operations and Evacuation of the 2/4th". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Levi, Werner (17 July 1946). "Portuguese Timor and the War". Far Eastern Survey. 15 (14): 221–223. doi:10.2307/3023062. JSTOR 3023062.

- "About Timor-Leste > Brief History of Timor-Leste: A History". Timor-Leste.gov.tl. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008.

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, Second Edition. MacMillan. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-333-57689-2.

- Jardine, pp. 50–51.

- "Official Web Gateway to the Government of Timor-Leste – Districts". Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Chega! The report of the commission for reception, truth, and reconciliation Timor-Leste". reliefweb. 28 November 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Benetech Human Rights Data Analysis Group (9 February 2006). "The Profile of Human Rights Violations in Timor-Leste, 1974–1999". A Report to the Commission on Reception, Truth and Reconciliation of Timor-Leste. Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG). pp. 2–4. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- Lutz, Nancy Melissa (20 November 1991). "Colonization, Decolonization and Integration: Language Policies in East Timor, Indonesia". Australian National University. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Niner, Sarah (2000). "A long journey of resistance: The origins and struggle of the CNRT". Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 32 (1–2): 11–18. doi:10.1080/14672715.2000.10415775. ISSN 0007-4810. S2CID 147535429.

- "Howard pushed me on E Timor referendum: Habibie". ABC News. 15 November 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- United States Congress House Committee on International Relations Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific; United States Congress Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs (2000). East Timor: A New Beginning? : Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific of the Committee on International Relations, House of Representatives, and the Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Sixth Congress, Second Session, February 10, 2000. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780160607820. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "One Man's Legacy in East Timor". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "United Nations Transitional Administration In East Timor – UNTAET". United Nations. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Etan/Us (15 February 2000). "UN takes over East Timor command". Etan.org. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Security Council (31 October 2001). "Council Endorses Proposal to Declare East Timor's Independence 20 May 2002". United Nations (Press release). Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "East Timor: More than 1,000 refugees return since beginning of month". ReliefWeb. 10 May 2002. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of East Timor". refworld. 20 May 2002. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- Aucoin, Louis; Brandt, Michele (1 April 2010). "East Timor's Constitutional Passage to Independence" (PDF). Framing the State in Times of Transition: Case Studies in Constitution Making. United States Institute of Peace. p. 254, 270. ISBN 978-1601270559.

- "Unanimous Assembly decision makes Timor-Leste 191st United Nations member state" (Press release). United Nations. 27 September 2002. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "UN wraps up East Timor mission". ABC News (Australia). 30 December 2012.

- "East Timor May Be Becoming Failed State". London. 13 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008.

- Ana Gomes (11 April 2007). "Delegation to Observe the Presidential Elections in the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Jose Cornelio Guterres (2008). "Timor-Leste: A Year of Democratic Elections". Southeast Asian Affairs: 359–372. JSTOR 27913367.

- "Shot East Timor leader 'critical'". BBC News. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "East Timor profile – Timeline". BBC News. 26 February 2018.

- Roughneen, Simon (12 May 2018). "East Timor votes in second general election in 10 months". Nikkei Asia.

- Cruz, Nelson de la (22 June 2018). "New East Timor PM pledges to bring unity after political deadlock". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- France-Presse, Agence (20 April 2022). "Timor-Leste presidential election: José Ramos-Horta wins in landslide". the Guardian.

- Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries". APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper. SSRN 1644026. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (24 January 2020). "Party Systems and Factionalism in Timor-Leste". Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. 39 (1): 167–186. doi:10.1177/1868103419889759. S2CID 214341149.

- "Timor-Leste Country Report 2022". Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "Timor-Leste". Freedom House. 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Aurel Croissant; Rebecca Abu Sharkh (21 May 2020). "As Good as It Gets? Stateness and Democracy in East Timor". In Croissant, Aurel; Hellmann, Olli (eds.). Stateness and Democracy in East Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108495745.

- Rui Graça Feijó (1 April 2015). "Timor-Leste: The Adventurous Tribulations of Local Governance after Independence". Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. 34 (1): 85–114. doi:10.1177/186810341503400104. S2CID 59459849.

- "Timor-Leste Final Report Parliamentary Election 2012" (PDF). European Union Election Observation Mission. 2012. p. 9. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Hynd, Evan (5 July 2012). "Timor's old guard marching on". Australian National University. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Joao da Cruz Cardoso (27 April 2022). "Timor-Leste: The new president needs to tune in". The Interpreter. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- "Diploma Ministerial No:199/GM/MAEOT/IX/09 de 15 de Setembro de 2009 Que fixa o número de Sucos e Aldeias em Território Nacional Exposição de motivos" (PDF), Jornal da Républica, Série I, N.° 33, 16 de Setembro de 2009, 3588–3620, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012

- Population and Housing Census 2015, Preliminary Results (PDF), Direcção-Geral de Estatística, retrieved 15 January 2018

- Filomeno Martins (28 December 2021). "Government to officially declare Atauro Island as new municipality in january 2022". Tatoli. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- Simião, Daniel S.; Silva, Kelly (21 November 2020). "Playing with ambiguity: The making and unmaking of local power in postcolonial Timor-Leste". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 31 (3): 333–346. doi:10.1111/taja.12377. S2CID 229471436.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (July 2010). "Decentralisation and the Central State in Timor-Leste" (PDF). 18th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Adelaide. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- "Lei N.º 3/2014 de 18 de Junho Cria a Região Administrativa Especial de Oe-Cusse Ambeno e estabelece a Zona Especial de Economia Social de Mercado" (PDF), Jornal da República, Série I, N.° 21, 18 de Junho de 2014, 7334–7341

- Laura S. Meitzner Yoder (29 April 2016). "The formation and remarkable persistence of the Oecusse-Ambeno enclave, Timor". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 47 (2): 302–303. doi:10.1017/S0022463416000084. S2CID 156975625.

- Butterworth, David; Dale, Pamela (October 2010). "Articulations of Local Governance in Timor-Leste : Lessons for Local Development under Decentralization". World Bank. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- Scambary, James (15 May 2019). Conflict, Identity, and State Formation in East Timor 2000 - 2017. Brill. ISBN 9789004396791.

- Sahin, Selver B. (1 August 2014). "Timor-Leste's Foreign Policy: Securing State Identity in the Post-Independence Period". Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. 33 (2): 3–25. doi:10.1177/186810341403300201. S2CID 54546263.

- Tansubhapol, Thanida (30 January 2011). "East Timor Bid to Join ASEAN Wins 'Strong Support'". Bangkok Post – via PressReader.

- Taylor-Leech, Kerry (2009). "The language situation in Timor-Leste". Current Issues in Language Planning. 10 (1): 1–68. doi:10.1080/14664200802339840. S2CID 146270920.

- Richard Baker (21 April 2007). "New Timor treaty 'a failure'". Theage.com.au. The Age Company Ltd. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- Strating, Rebecca (2017). "Timor-Leste's foreign policy approach to the Timor Sea disputes: pipeline or pipe dream?". Australian Journal of International Affairs. 71 (3): 259–283. doi:10.1080/10357718.2016.1258689. S2CID 157488844.

- "Australia and East Timor sign historic maritime border deal". BBC News. 7 March 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- "Australia ratifies maritime boundaries with East Timor". Reuters. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- "Chapter Six: Asia". The Military Balance. International Institute for Strategic Studies. 121 (1): 307–308. 24 February 2001. doi:10.1080/04597222.2021.1868795. ISSN 0459-7222. S2CID 232050863.

- Berlie, Jean A. (1 October 2017). "A Socio-Historical Essay: Traditions, Indonesia, Independence, and Elections". East Timor's Independence, Indonesia and ASEAN. Springer. ISBN 9783319626307.

- "Timor-Leste : Country Environmental Analysis". World Bank Group. July 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- Molnar, Andrea Katalin (17 December 2009). Timor Leste: Politics, History, and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 9781135228842.

- Deeley, Neil (2001). The International Boundaries of East Timor. International Boundaries Research Unit. ISBN 9781897643426.

- "Climate Risk Country Profile - Timor-Leste". Asian Development Bank, World Bank Group. 18 November 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Dixon, David (1 March 2021). "Demarcating the Frontiers of Australia, Indonesia and Timor-Leste". Frontiers in International Environmental Law: Oceans and Climate Challenges. Brill. pp. 43–74. doi:10.1163/9789004372887_003. ISBN 9789004372887. S2CID 235518614.

- Posma Sariguna Johnson Kennedy; Suzanna Josephine L. Tobing; Adolf Bastian Heatubun; Rutman Lumbantoruan (2021). "The Maritime Border Management of Indonesia and Timor Leste: By Military Approach or Welfare Approach?" (PDF). Proceedings of Airlangga Conference on International Relations (ACIR 2018) - Politics, Economy, and Security in Changing Indo-Pacific Region: 348–354. doi:10.5220/0010277003480354. ISBN 978-989-758-493-0.

- "Catches by Taxon in the waters of Timor Leste". Sea Around Us. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- "Mount Ramelau". Gunung Bagging. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Nino Konis Santana National Park declared as Timor-Leste's (formerly East Timor) first national park". Petside. Wildlife Extra.

- Norwegian energy and Water Resources Directorate (NVE) (2004), Iralalaro Hydropower Project Environmental Assessment

- "ReefGIS – Reefs At Risk – Global 1998". Reefgis.reefbase.org. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- "Country Partnership Strategy: Timor-Leste 2016–2020 Environment Assessment (Summary)" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- de Brouwer, Gordon (2001), Hill, Hal; Saldanha, João M. (eds.), East Timor: Development Challenges For The World's Newest Nation, Canberra, Australia: Asia Pacific Press, pp. 39–51, ISBN 978-0-3339-8716-2

- Scheiner, Charles (30 September 2021). "Timor-Leste economic survey: The end of petroleum income". Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies. 8 (2): 253–279. doi:10.1002/app5.333. S2CID 244233899.

- "Timor-Leste Economic Report, December 2021 : Steadying the Ship". World Bank Group. 1 December 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- "Timor-Leste 2016 Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings" (PDF). General Directorate of Statistics. 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Angus Grigg (30 April 2021). "Less than 20 years after independence, Timor-Leste is running on fumes". Financial Review. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- "U.S. Relations With Timor-Leste". U.S. Department of State. 3 July 2012.

- "Highlights of the 2010 Census Main Results in Timor-Leste" (PDF). Direcção Nacional de Estatística. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- Joao da Cruz Cardoso (1 March 2021). "Why is Timor-Leste Still Unable to Diversify its Economy?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- John, Samuel; Papyrakis, Elissaios; Tasciotti, Luca (2020). "Is there a resource curse in Timor-Leste? A critical review of recent evidence". Development Studies Research. 7 (1): 141–152. doi:10.1080/21665095.2020.1816189. S2CID 224995979.

- "Keine Lust auf Massentourismus? Studie: Die Länder mit den wenigsten Urlaubern der Welt". TRAVELBOOK. 10 September 2018.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Government of Timor-Leste". Timor-leste.gov.tl. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Dickson, Paul (2006). Labels for Locals: What to Call People from Abilene to Zimbabwe. Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-088164-1.

- "The International Thesaurus of Refugee Terminology". UNHCR & FMO. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Fox, James J.; Soares, Dionisio Babo (2000). Out of the Ashes: Destruction and Reconstruction of East Timor. C. Hurst. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-85065-554-1.

- "Human Development Report 2020: Timor-Leste" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Udoy Sankar Saikia; Gouranga L. Dasvarma; Tanya Wells-Brown (2009). "The world's highest fertility in Asia's newest nation: an investigation into reproductive behaviour of women in Timor-Leste". Princeton University. p. 2. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Fertility Summary of the Thematic Report" (PDF). General Directorate of Statistics. 2015. p. 6. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Kingsbury, Damien (March 2010). "National identity in Timor-Leste: challenges and opportunities". South East Asia Research. 18 (1): 133–159. doi:10.5367/000000010790959820. JSTOR 23750953. S2CID 144171942.

- Boac, Ernesto D. (2001). The East Timor and Mindanao Independence Movements: A Comparative Study. U.S. Army War College. p. 3.

- Berlie, Jean A. (2015), "Chinese in East Timor: Identity, Society and Economy", HumaNetten (35): 37–49, doi:10.15626/hn.20153503

- Huber, Juliette (1 September 2021). "At the Periphery of Nanyang: The Hakka Community of Timor-Leste". Sinitic Voices across the Southern Seas. Brill. pp. 52–90. doi:10.1163/9789004473263_004. ISBN 9789004473263. S2CID 250178726.

- Constâncio Pinto; Matthew Jardine (1997). East Timor's Unfinished Struggle: Inside the East Timorese Resistance. South End Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-89608-541-1.

- "Relations with a new nation, How far South East is New Delhi prepared to go?". www.etan.org. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- "Languages of East Timor". Ethnologue.

- "Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- "Language". General Directorate of Statistics. 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- Catharina Williams-van Klinken; Rob Williams (2015). "Mapping the mother tongue in Timor-Leste Who spoke what where in 2010?". Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "Language", Population and Housing Census of Timor-Leste, 2015, Timor-Leste Ministry of Finance

- Ramos-Horta, J. (20 April 2012). "Timor Leste, Tetum, Portuguese, Bahasa Indonesia or English?". The Jakarta Post.

- The Impact of the Language Directive on the Courts in East Timor (PDF) (Report). Dili, East Timor: Judicial System Monitoring Programme. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "O estímulo ao uso da língua portuguesa em Timor Leste e Guiné Bissau". Blog of the International Portuguese Language Institute (in Portuguese). 29 May 2015.

- Fernandes, Neila (6 May 2021). "Longuinhos pede a académicos que utilizem a língua portuguesa na transmissão de conhecimento". Tatoli. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Jessica Gardner. "Timor-Leste Population and Housing Census 2015 Analytical Report on Gender Dimensions" (PDF). United Nations Population Fund. p. 34. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "National adult literacy rates (15+), youth literacy rates (15–24) and elderly literacy rates (65+)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- Roslyn Appleby (30 August 2010). ELT, Gender and International Development: Myths of Progress in a Neocolonial World. Multilingual Matters. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-84769-303-7.

- Robinson, Geoffrey (2010). If You Leave Us Here, We Will Die: How Genocide Was Stopped in East Timor. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 72.

- "Table 5.7 – Profile Of Students That Attended The 2004/05 Academic Year By Rural And Urban Areas And By District". Direcção Nacional de Estatística. Archived from the original on 14 November 2009.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Governo de Timor-Leste.

- Brown, Bernardo; Chambon, Michel (4 February 2022). "Catholicism's Overlooked Importance in Asia". The Diplomat. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- Cavanaugh, Ray (24 April 2019). "Timor-Leste: A young nation with strong faith and heavy burdens". The Catholic World Report.

- "Timor-Leste: Demographic and Health Survey, 2016" (PDF). General Directorate of Statistics, Ministry of Planning and Finance & Ministry of Health. p. 35. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- Head, Jonathan (5 April 2005). "East Timor mourns 'catalyst' Pope". BBC News.

- "Pope Benedict XVI erects new diocese in East Timor". Catholic News Agency.

- Hajek, John; Tilman, Alexandre Vital (1 October 2001). East Timor Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-74059-020-4.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Timor-Leste. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Leach, Michael (8 December 2016). Nation-Building and National Identity in Timor-Leste. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781315311647.

- Rosangela Tenorio; Jairo da Costa Junior, eds. (3 March 2022). Homan Futuru: Timor-Leste Traditional Housing. University of Western Australia.

- Nico de Jonge (2013). "Traditional Arts in Timorese Cultures". Dallas Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Tais, traditional textile". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "The Project for Study on Dili Urban Master Plan in the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Japan International Cooperation Agency. October 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Morris, Chris (1992). "The People of East Timor". A Traveller's Dictionary in Tetun-English and English-Tetun. Baba Dook Books. ISBN 9780959192223.

- "Literatura timorense em língua portuguesa" [Timorese literature in the Portuguese language]. lusofonia.x10.mx (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 29 September 2019.

- "East Timor's president accepts Xanana Gusmao's resignation". ABC News. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Bibliography

- Cashmore, Ellis (1988). Dictionary of Race and Ethnic Relations. New York: Routledge. ASIN B000NPHGX6.

- Charny, Israel W., ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Genocide. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. ISBN 0-87436-928-2.

- Dunn, James (1996). East Timor: A People Betrayed. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Durand, Frédéric (2006). East Timor: A Country at the Crossroads of Asia and the Pacific, a Geo-Historical Atlas. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 9749575989.

- Durand, Frédéric (2016). History of Timor Leste. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 978-616-215-124-8.

- Groshong, Daniel J (2006). Timor-Leste: Land of Discovery. Hong Kong: Tayo Photo Group. ISBN 988987640X.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (1999). Timor Loro Sae: 500 Years. Macau: Livros do Oriente. ISBN 972-9418-69-1.