ASEAN

ASEAN (UK: /ˈæsiæn/ ASS-ee-an, US: /ˈɑːsiɑːn, ˈɑːzi-/ AH-see-ahn, AH-zee-an),[9][10][11] officially the Association of Southeast Asian Nations,[12] is a political and economic union of 10 member states in Southeast Asia, which promotes intergovernmental cooperation and facilitates economic, political, security, military, educational, and sociocultural integration between its members and countries in the Asia-Pacific. The union has a total area of 4,522,518 km2 (1,746,154 sq mi) and an estimated total population of about 668 million.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flag

Emblem

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: "One Vision, One Identity, One Community"[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "The ASEAN Way" | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Logo | |||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Member states shown in dark green. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretariat | Jakarta[lower-alpha 1] 6°14.3353′S 106°47.9554′E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Jakarta 6°11.6962′S 106°49.3837′E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Working language | English[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages of contracting states | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaders | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Secretary-General | Lim Jock Hoi | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Chairmanship of ASEAN | Cambodia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Bangkok Declaration | 8 August 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Charter | 16 December 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 4,522,518[7] km2 (1,746,154 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 2021 estimate | 667,393,019[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Density | 144/km2 (373.0/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | |||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | |||||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2021) | high | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+06:30 to +09:00 (ACT) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Website www | |||||||||||||||||||||

ASEAN's primary objective was to accelerate economic growth and through that social progress and cultural development. A secondary objective was to promote regional peace and stability based on the rule of law and the principle of UN Charter. With some of the fastest growing economies in the world, ASEAN has broadened its objective beyond the economic and social spheres. In 2003, ASEAN moved along the path similar to the European Union (EU) by agreeing to establish an ASEAN community that consists of three pillars: the ASEAN Security Community, the ASEAN Economic Community, and the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community. The ten stalks of rice in the ASEAN flag and insignia represents the ten Southeast Asian countries bound together in solidarity.

ASEAN regularly engages other countries in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. A major partner of UN, SCO, PA, GCC, MERCOSUR, CELAC and ECO,[13] ASEAN maintains a global network of alliances and dialogue partners and is considered by many as a global powerhouse,[14][15] the central union for cooperation in Asia-Pacific, and a prominent and influential organization. It is involved in numerous international affairs, and hosts diplomatic missions throughout the world.[16][17][18][19] The organization's success has become the driving force of some of the largest trade blocs in history, including APEC and RCEP.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

History

Founding

ASEAN was preceded by an organisation formed on 31 July 1961 called the Association of Southeast Asia (ASA), a group consisting of Thailand, the Philippines, and the Federation of Malaya.[26][27] ASEAN itself was created on 8 August 1967, when the foreign ministers of five countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, signed the ASEAN Declaration.[28] As set out in the Declaration, the aims and purposes of ASEAN are to accelerate economic growth, social progress, and cultural development in the region, to promote regional peace, collaboration and mutual assistance on matters of common interest, to provide assistance to each other in the form of training and research facilities, to collaborate for better utilization of agriculture and industry to raise the living standards of the people, to promote Southeast Asian studies and to maintain close, beneficial co-operation with existing international organisations with similar aims and purposes.[29][30]

The creation of ASEAN was initially motivated by the desire to contain communism. Communism had taken a foothold in mainland Asia with the Soviet Union occupation of the northern Korean peninsula after World War II, establishing communist governments in North Korea (1945), People's Republic of China (1949) and portions of former French Indochina with North Vietnam (1954), accompanied by the communist insurgency "Emergency" in British Malaya and unrest in the recently independent Philippines from the U S. in the early 1950s.

These events also encouraged the earlier formation of SEATO (South East Asia Treaty Organization) led by the United States and United Kingdom along with Australia with several Southeast Asian partners in 1954 as a "containment" extension and an eastern version of the early defensive bulwark NATO in western Europe of 1949.[31] However, the local member states of ASEAN group achieved greater cohesion in the mid-1970s following a change in the balance of power after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War in April 1975 and the decline of SEATO.

ASEAN's first summit meeting, held in Bali, Indonesia in 1976, resulted in an agreement on several industrial projects and the signing of a Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, and a Declaration of Concord. The end of the Cold War allowed ASEAN countries to exercise greater political independence in the region, and in the 1990s, ASEAN emerged as a leading voice on regional trade and security issues.[32]

On 15 December 1995, the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty was signed to turn Southeast Asia into a nuclear-weapon-free zone. The treaty took effect on 28 March 1997 after all but one of the member states had ratified it. It became fully effective on 21 June 2001 after the Philippines ratified it, effectively banning all nuclear weapons in the region.[33]

Expansion

On 7 January 1984, Brunei became ASEAN's sixth member[34] and on 28 July 1995, following the end of the Cold War, Vietnam joined as the seventh member.[35] Laos and Myanmar (formerly Burma) joined two years later on 23 July 1997.[36] Cambodia was to join at the same time as Laos and Myanmar, but a coup in 1997 and other internal instability delayed its entry.[37] It then joined on 30 April 1999 following the stabilization of its government.[36][38]

In 2006, ASEAN was given observer status at the United Nations General Assembly.[39] In response, the organisation awarded the status of "dialogue partner" to the UN.[40]

Commonality

Besides sharing similar geographical location, Southeast Asian nations are considered to have been at cultural crossroads between East Asia and South Asia, located at critical junctions of the South China Sea as well as the Indian Ocean, as well as having had received much influence from Islamic and Persian influences prior to the European colonial ages.[41][42]

Since around 100 BCE, the Southeast Asian archipelago occupied a central position at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea trading routes which stimulated the economy and the influx of ideas.[43] This included the introduction of abugida scripts to Southeast Asia as well as the Chinese script to Vietnam. Besides various indigenous scripts, various abugida Brahmic scripts were widespread in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Malay etc. Historically, scripts such as Pallava, Kawi (from ancient Tamil script) and Rencong or Surat Ulu were used to write Old Malay, until they were replaced by Jawi during Islamic missionary missions in the Malay Archipelago.[44]

Historical European colonial influence to various ASEAN countries, including French Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Laos & Cambodia), British Burma, Malaya and Borneo (present-day Myanmar, Malaysia & Singapore, and Borneo), Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia), Spanish East Indies (present-day Philippines and various other colonies), and Portuguese Timor (present-day Timor-Leste) influenced all Southeast Asian countries, with only Thailand (called Siam then) being the only Southeast Asian country not taken as a European colony.[45] Siam (present-day Thailand), served as a convenient buffer state, sandwiched between British Burma and French Indochina, but its kings had to contend with unequal treaties as well as British and French political interference and territorial losses after the Franco-Siamese War in 1893 and the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909.[46] Relative to the history of Southeast Asia, European influence is brief. European influence included the introduction of the Latin alphabet and various European religions and concepts.

The Japanese Empire, in the vein of Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere concept, sought to unite and create a pan-Asian identity against Western colonial occupation. However, this ended poorly, as the intentions of the Japanese were not as altruistic as seemed (see Japanese War Crimes)[47][48] Atomic bombings of Japan eventuated in decolonization movements throughout the Southeast Asian region, resulting in mostly independent ASEAN states today.

The ASEAN Charter

On 15 December 2008, member states met in Jakarta to launch a charter, signed in November 2007, to move closer to "an EU-style community".[49] The charter turned ASEAN into a legal entity and aimed to create a single free-trade area for the region encompassing 500 million people. President of Indonesia Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono stated: "This is a momentous development when ASEAN is consolidating, integrating, and transforming itself into a community. It is achieved while ASEAN seeks a more vigorous role in Asian and global affairs at a time when the international system is experiencing a seismic shift". Referring to climate change and economic upheaval, he concluded: "Southeast Asia is no longer the bitterly divided, war-torn region it was in the 1960s and 1970s".

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 was seen as a threat to the charter's goals,[50] and also set forth the idea of a proposed human rights body to be discussed at a future summit in February 2009. This proposition caused controversy, as the body would not have the power to impose sanctions or punish countries which violated citizens' rights and would, therefore, be limited in effectiveness.[51] The body was established later in 2009 as the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR). In November 2012, the commission adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration.[52]

Vietnam held the chair of ASEAN in 2020. Brunei held it in 2021.

Myanmar crisis

Since 2017, political, military and ethnic affairs in Myanmar have posed unusual challenges for ASEAN, creating precedent-breaking situations and threatening the traditions and unity of the group, and its global standing[53][54][55][56][57]—with ASEAN responses indicating possible fundamental change in the nature of the organization.[58][59][60][61][62]

Rohingya genocide

The Rohingya genocide erupting in Myanmar in August 2017—killing thousands of Rohingya people in Myanmar,[63][64][65] driving most into neighboring Bangladesh, and continuing for months[66][67][68][69]—created a global outcry demanding ASEAN take action against the civilian-military coalition government of Myanmar, which had long discriminated against the Rohingya, and had launched the 2017 attacks upon them.[58][70][71][72]

As the Rohingya were predominantly Muslim (in Buddhist-dominated Myanmar), and the ethnic cleansing was framed in religious terms, other largely-Muslim ASEAN nations (particularly Malaysia,[73][74][75] Indonesia,[58][73] Singapore,[58] and Brunei[58][73]) objected, some strongly[58][53][76]—and also objected to the burden of Rohingya refugees arriving on their shores[72] (as did ASEAN neighbors Buddhist-dominated Thailand[72][77] and Muslim-dominated observer-nation Bangladesh[78][79][80]

Myanmar's civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, also reportedly asked ASEAN for help with the Rohingya crisis, in March 2018, but was rebuffed by ASEAN's chair, who said it was an "internal matter."[74]

ASEAN had a longstanding firm policy of "non-interference in the internal affairs of member nations," and was reluctant, as an organization, to take sides in the conflict, or act materially.[58][73][81][82]

Internal[83] and international[58][84] pressure mounted for ASEAN to take a firmer stance on the Rohingya crisis, and by late 2018, the group's global credibility was threatened by its inaction.[58][72][85]

In response, ASEAN began to put pressure on Myanmar to be less hostile to the Rohingya, and to hold accountable those responsible for atrocities against them.[58][85][77]

However ASEAN's positions on the issue largely divided on religious lines, with Muslim nations siding more with the Rohingya, while Buddhist nations initially sided more with Myanmar's government, threatening a sectarian division of ASEAN. Authoritarian ASEAN nations, too (mostly Buddhist), were less enthusiastic than democratic ASEAN nations (mostly Muslim), about holding Myanmar officials accountable for crimes against their Rohingya minority.[58][73][78]

But, by late-2018, most ASEAN nations had begun to advocate for a more forceful ASEAN response to the Rohingya crisis, and a harder line against Myanmar—breaking with the group's traditional policy of "non-interference" in members' "internal affairs"—a break emphasized by the Rohingya crisis being formally placed on the December 2018 ASEAN summit agenda.[58][77][86]

In early 2019, Bangladesh suggested that Myanmar create a safe haven for the Rohingya within its borders, under ASEAN supervision[78] (later expanding that idea to include India, China and Japan among the supervisors).[87][88]

In mid-2019, ASEAN was heavily criticized by human rights organizations for a report, which ASEAN commissioned, which turned out to praise Myanmar's work on Rohingya repatriation, while glossing over atrocities and abuses against the Rohingya.[89][84][90][91][92]

The June 2019 ASEAN summit was shaken by the Malaysian foreign minister's declaration that persons responsible for the abuses of the Rohingya be prosecuted and punished—conduct unusually undiplomatic at ASEAN summits.[91] ASEAN pressed Myanmar for a firm timeline for the repatriation of Rohingya refugees who fled Myanmar[93]—pressuring Myanmar to provide "safety and security for all communities in Rakhine State as effectively as possible and facilitate the voluntary return of displaced persons in a safe, secure and dignified manner."[94]

In August 2019, the annual ASEAN Foreign Ministers' meeting concluded with a joint communique calling on Myanmar's government to guarantee the safety of all Rohingya—both in Myanmar and in exile—and pushed for more dialogue with the refugees about their repatriation to Myanmar. But later that month ASEAN's Inter-Parliamentary Assembly (AIPA) supported Myanmar's "efforts" on repatriation, with aid, restraining some members' desire for more intrusive proposals.[95][96]

By January 2020, ASEAN had made little progress to prepare safe conditions for the Rohingyas' return to Myanmar.[97][72]

2021 coup

On 1 February 2021, the day before a newly elected slate of civilian leaders was to take office in Myanmar, a military junta overthrew Myanmar's civilian government in a coup d'etat, declaring a national state of emergency, imposing martial law, arresting elected civilian leaders, violently clamping down on dissent, and replacing civilian government with the military's appointees.[98][99][100][101]

Widespread protests and resistance erupted, and elements of the civilian leadership formed an underground "National Unity Government" (NUG). Global opposition to the coup emerged, and global pressure was brought on ASEAN to take action.[102][103][101][104][105]

Initially, ASEAN remained detached from the controversy, though Muslim-dominated members (mostly democracies, already vocal against the Rohingya genocide) expressed strong objection to the coup, while the mostly-Buddhist authoritarian members of ASEAN remained quiet.[101][57][53]

In April 2021, in the first-ever ASEAN summit called to deal primarily with a domestic crisis in a member state,[53] ASEAN leaders met with Myanmar's coup leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, and agreed to a five-point consensus solution to the crisis in Myanmar:[99][106]

- 1) The immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar;

- 2) Constructive dialogue among all parties concerned... to seek a peaceful solution in the interests of the people;

- 3) Mediation facilitated by an envoy of ASEAN's Chair, with the assistance of ASEAN's Secretary-General;

- 4) Humanitarian assistance provided by ASEAN through its AHA Centre; and

- 5) A visit to Myanmar, by the special envoy and delegation, to meet with all parties concerned.

The ASEAN agreement with Myanmar drew strong criticism from over 150 human rights organizations for its lax approach,[107][100] yet the Myanmar junta did not comply with any of the points of the plan.[100][108][109][101]

On 18 June 2021, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) — in a rare move, with a nearly unanimous resolution — condemned Myanmar's coup, and called for an arms embargo against the country. The UNGA consulted with ASEAN and integrated most of ASEAN's 5-point consensus into the resolution (adding demands that the junta release all political prisoners). But, while Communist Vietnam voted "yes," along with the ASEAN democracies (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines), most authoritarian ASEAN states (Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Brunei) abstained.[110][111]

In October 2021, despite its consensus agreement with ASEAN, Myanmar's junta refused to allow ASEAN representatives to speak with Myanmar's deposed and imprisoned civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[109][112][101]

Following lobbying by the United Nations, United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and other nations, ASEAN declined to invite Myanmar's Gen. Hlaing to represent Myanmar at ASEAN's October 2021 summit — the first time in ASEAN's history that it did not invite a political leader from a member nation to one of its summits. Nor did ASEAN invite a representative of Myanmar's underground National Unity Government, saying it would consider inviting a non-political representative of the country, instead, (though none was actually invited).[108][113][109][101][114][104]

The unusual ASEAN action was widely seen as a major setback for the Myanmar junta's attempt to achieve global recognition as the legitimate government of Myanmar,[61][113][109][101] and a sign of broader change in the behavior and role of ASEAN.[60][61][62][101]

South China Sea disputes

With perceptions that there have been multiple incursions into the South China Sea by China, with land, islands and resources all having had previous overlapping claims between Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and various other countries, China's claim into the region is late and is seen as incursive by many southeast Asian countries as of 2022, potentially a reflection of the threat of Chinese expansionism into the region.[115][116] This follows the infamous 11 dash line that was produced by the Republic of China (Taiwan), followed by the infamous 9-dash line by the People's Republic of China. ASEAN sought for a more unified response against what it perceived to be Chinese penetration and hegemony into the region. There have been attempts to counterbalance the sway of China by attempting to align with other nations such as Western powers.[117] The Chinese (and also Taiwan) have employed several strategies in an attempt to wrestle hold of South China Sea islands, such as Chinese salami slicing strategy, and cabbage tactics from China. There has also been calls to end Taiwan's illegal military actions in the South China Sea, called the East Sea in Vietnamese.[118] Additionally, China passed a law in January 2021 allowing its coast guard to fire on foreign vessels, causing greater concern amongst ASEAN states.[119] It is considered that the Cham people, indigenous to Central and South Vietnam, were the 'ancient rulers of the South China Sea', having had conducted extensive trade and maritime routes throughout the Southeast Asian region.[120]

Member states

List of member states

| State | Capital | Accession[121] |

|---|---|---|

| Brunei | Bandar Seri Begawan | 7 January 1984 |

| Cambodia | Phnom Penh | 30 April 1999 |

| Indonesia | Jakarta | 8 August 1967 |

| Laos | Vientiane | 23 July 1997 |

| Malaysia | Kuala Lumpur | 8 August 1967 |

| Myanmar | Napyidaw | 23 July 1997 |

| Philippines | Manila | 8 August 1967 |

| Singapore | Singapore | 8 August 1967 |

| Thailand | Bangkok | 8 August 1967 |

| Vietnam | Hanoi | 28 July 1995 |

Observers

There are currently two states seeking accession to ASEAN: Papua New Guinea[122][123] and East Timor.[124]

- Accession of Papua New Guinea to ASEAN (observer status since 1976)

- Accession of East Timor to ASEAN (since 2002)

Demographics

Population

As of 1 July 2019, the population of the ASEAN was about 655 million people (8.5% of the world population).[125][126] In 2019, 55.2 million children were age 0-4 and 46.3 million were older than 65 in the ASEAN. This corresponds to 8.4% and 7.1% of the total ASEAN population. The region's population growth is 1.1% per year with Thailand being the smallest at 0.2% per year, and Cambodia being the largest at 1.9% per year. ASEAN's sex ratio is 99.6, with 326.4 million males and 327.8 million females.

Urbanisation

The ASEAN contains about 31 urban areas with populations of over one million. The largest urban area in the ASEAN is Jakarta[127] followed by Manila, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Kuala Lumpur, Bandung, Hanoi, Surabaya, Yangon, and Singapore, all with an urban population of over 5 million.[127] Over 49.5% or 324 million people live in urban areas.

| Rank | Name | Country | Pop. | Rank | Name | Country | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jakarta  Manila |

1 | Jakarta | Indonesia | 34,540,000 | 11 | Medan | Indonesia | 3,632,000 |  Bangkok .jpg.webp) Ho Chi Minh City |

| 2 | Manila | Philippines | 23,088,000 | 12 | Cebu City | Philippines | 2,275,000 | ||

| 3 | Bangkok | Thailand | 17,066,000 | 13 | Phnom Penh | Cambodia | 2,177,000 | ||

| 4 | Ho Chi Minh City | Vietnam | 13,312,000 | 14 | Semarang | Indonesia | 1,992,000 | ||

| 5 | Kuala Lumpur | Malaysia | 8,285,000 | 15 | Johor Bahru | Malaysia | 1,981,000 | ||

| 6 | Bandung | Indonesia | 7,065,000 | 16 | Makassar | Indonesia | 1,952,000 | ||

| 7 | Hanoi | Vietnam | 6,576,000 | 17 | Palembang | Indonesia | 1,889,000 | ||

| 8 | Surabaya | Indonesia | 6,499,000 | 18 | Mandalay | Myanmar | 1,633,000 | ||

| 9 | Yangon | Myanmar | 6,314,000 | 19 | Hai Phong | Vietnam | 1,623,000 | ||

| 10 | Singapore | Singapore | 5,745,000 | 20 | Yogyakarta | Indonesia | 1,568,000 | ||

The ASEAN Way

The "ASEAN Way" refers to a methodology or approach to solving issues that respect Southeast Asia's cultural norms. Masilamani and Peterson summarise it as "a working process or style that is informal and personal. Policymakers constantly utilise compromise, consensus, and consultation in the informal decision-making process... it above all prioritises a consensus-based, non-conflictual way of addressing problems. Quiet diplomacy allows ASEAN leaders to communicate without bringing the discussions into the public view. Members avoid the embarrassment that may lead to further conflict."[128] It has been said that the merits of the ASEAN Way might "be usefully applied to global conflict management". However, critics have argued that such an approach can be only applied to Asian countries, to specific cultural norms and understandings notably, due to a difference in mindset and level of tension.[129]: pp113-118

Critics object, claiming that the ASEAN Way's emphasis on consultation, consensus, and non-interference forces the organisation to adopt only those policies which satisfy the lowest common denominator. Decision-making by consensus requires members to see eye-to-eye before ASEAN can move forward on an issue. Members may not have a common conception of the meaning of the ASEAN Way. Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos emphasize non-interference while older member countries focus on co-operation and co-ordination. These differences hinder efforts to find common solutions to particular issues, but also make it difficult to determine when collective action is appropriate in a given situation.[130]: 161–163

Structure

Beginning in 1997, heads of each member state adopted the ASEAN Vision 2020 during the group's 30th anniversary meeting held in Kuala Lumpur. As a means for the realisation of a single ASEAN community, this vision provides provisions on peace and stability, a nuclear-free region, closer economic integration, human development, sustainable development, cultural heritage, being a drug-free region, environment among others. The vision also aimed to "see an outward-looking ASEAN playing a pivotal role in the international fora, and advancing ASEAN's common interests".[131][132]

ASEAN Vision 2020 was formalised and made comprehensive through the Bali Concord II in 2003. Three major pillars of a single ASEAN community were established: Political-Security Community (APSC), Economic Community (AEC) and Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC).[133][12][134][135][136] To fully embody the three pillars as part of the 2015 integration, blueprints for APSC and ASCC were subsequently adopted in 2009 in Cha-am, Thailand.[137] The ASEAN Community, initially planned to commence by 2020, was accelerated to begin by 31 December 2015.[138] It was decided during the 12th ASEAN Summit in Cebu in 2007.[139]

At the 23rd ASEAN Summit in November 2013, leaders decided to develop a post-2015 Vision and created the High-Level Task Force (HLTF) that consists of ten high-level representatives from all member states. The Vision was adopted at the 27th Summit in November 2015 in Kuala Lumpur. The ASEAN community would revise and renew its vision every ten years to provide a framework for continuous development and further integration.

The terms in the post-2015 Vision are divided into four subcategories, namely APSC, AEC, ASCC, and Moving Forward. APSC issues are covered under articles 7 and 8. The former generally states the community's overall aspiration to aim for a united, inclusive and resilient community. It also puts human and environmental security as crucial points. Deepening engagement with both internal and external parties are also stressed to contribute to international peace, security and stability.[140] The "Moving Forward" subcategory implies the acknowledgement of weaknesses of the institution's capacity to process and coordinate ASEAN work. Strengthening ASEAN Secretariat and other ASEAN organs and bodies is therefore desired. There is also a call for a higher level of ASEAN institutional presence at the national, regional and international levels.

Additionally, ASEAN institutional weakness has been further amplified by the ineffectiveness of its initiatives in fighting against COVID-19. ASEAN has been making painstaking efforts to combat the pandemic by establishing both intra and extra-regional ad hoc agencies such as theASEAN-China Ad-Hoc Health Ministers Joint Task Force, the Special ASEAN Summit on the COVID-19, COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund, and the Special ASEAN Plus Three Summit on COVID-19. These mechanisms aim to facilitate senior discussions among regional actors on how to contain the pandemic's spread and reduce its negative impacts. However, their practical implementations are still insignificant when the cooperation among member states is insubstantial, as illustrated by the polarisation of their COVID-19 policies and the high number of cases and deaths in the region.[141]

AEC Blueprint

The AEC aims to "implement economic integration initiatives" to create a single market for member states.[142][143] The blueprint that serves as a comprehensive guide for the establishment of the community was adopted on 20 November 2007 at the 13th ASEAN Summit in Singapore.[142][144] Its characteristics include a single market and production base, a highly competitive economic region, a region of fair economic development, and a region fully integrated into the global economy. The areas of cooperation include human resources development, recognition of professional qualifications, closer consultation economic policies, enhanced infrastructure and communications connectivity, integrating industries for regional sourcing, and strengthening private sector involvement. Through the free movement of skilled labour, goods, services and investment, ASEAN would rise globally as one market, thus increasing its competitiveness and opportunities for development.[145]

APSC Blueprint

During the 14th ASEAN Summit, the group adopted the APSC Blueprint.[146] This document is aimed at creating a robust political-security environment within ASEAN, with programs and activities outlined to establish the APSC by 2016. It is based on the ASEAN Charter, the ASEAN Security Community Plan of Action, and the Vientiane Action Program. The APSC aims to create a sense of responsibility toward comprehensive security and a dynamic, outward-looking region in an increasingly integrated and interdependent world.

The ASEAN Defence Industry Collaboration (ADIC) was proposed at the 4th ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting (ADMM) on 11 May 2010 in Hanoi.[147] It has the purpose, among others, to reduce defence imports from non-ASEAN countries by half and to further develop the defence industry in the region.[148] It was formally adopted on the next ADMM on 19 May 2011, in Jakarta, Indonesia.[149] The main focus is to industrially and technologically boost the security capability of ASEAN,[150][151] consistent with the principles of flexibility and non-binding and voluntary participation among the member states.[152][153] The concept revolves around education and capability-building programs to develop the skills and capabilities of the workforce, production of capital for defence products, and the provision of numerous services to address the security needs of each member state. It also aims to develop an intra-ASEAN defence trade.[147] ADIC aims to establish a strong defence industry relying on the local capabilities of each member state and limit annual procurement from external original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).[147] Countries like the US, Germany, Russia, France, Italy, UK, China, South Korea, Israel, and the Netherlands are among the major suppliers to ASEAN.[154] ASEAN defence budget rose by 147% from 2004 to 2013 and is expected to rise further in the future.[155] Factors affecting the increase include economic growth, ageing equipment, and the plan to strengthen the establishment of the defence industry.[156] ASEANAPOL is also established to enhance cooperation on law enforcement and crime control among police forces of member states.[157]

However, the unequal level of capabilities among the member states in the defence industry and the lack of established defence trade pose challenges.[150] Before the adoption of the ADIC concept, the status of the defence industry base in each of the member states was at a different level.[150] Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand are among the top member states with an established defence industry base, but they possess different levels of capacity. The remaining member states have yet to develop and enhance their capabilities.[147][150] Indonesia and Singapore are among the most competitive players; the former is the only one recognised as one of the top 100 global defence suppliers from between 2010 and 2013.[158][159] ASEAN member states purchase virtually no defence products from within ASEAN. Singapore purchases products from Germany, France, and Israel. Malaysia purchased only 0.49% from ASEAN, Indonesia 0.1%, and Thailand 8.02%.[150]

The ASEAN Convention on Counter-Terrorism (ACCT) serves as a framework for regional cooperation to counter, prevent, and suppress terrorism and deepen counter-terrorism cooperation.[160] It was signed by ASEAN leaders in 2007. On 28 April 2011, Brunei ratified the convention and a month later, the convention came into force. Malaysia became the tenth member state to ratify ACCT on 11 January 2013.[160]

ASCC Blueprint

The ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) was also adopted during the 14th ASEAN Summit.[161] It envisions an "ASEAN Community that is people-centered and socially responsible with a view to achieving enduring solidarity and unity among the countries and peoples of ASEAN by forging a common identity and building a caring and sharing society which is inclusive and harmonious where the well-being, livelihood, and welfare of the peoples are enhanced". Among its focus areas include human development, social welfare and protection, social justice and rights, environmental sustainability, building the ASEAN identity, and narrowing the development gap.

To track the progress of the AEC, a compliance tool called the AEC Scorecard was developed based on the EU Internal Market Scorecard.[162] It is the only one in effect[163] and is expected to serve as an unbiased assessment tool to measure the extent of integration and the economic health of the region. It is expected to provide relevant information about regional priorities, and thus foster productive, inclusive, and sustainable growth.[164] It makes it possible to monitor the implementation of ASEAN agreements, and the achievement of milestones indicated in the AEC Strategic Schedule. The scorecard outlines specific actions that must be undertaken collectively and individually to establish AEC by 2015.[164] To date, two official scorecards have been published, one in 2010,[165] and the other in 2012.[166][162] However, the scorecard is purely quantitative, as it only examines whether a member state has performed the AEC task or not. The more "yes" answers, the higher the score.[163]

While Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand have eliminated 99.65% of their tariff lines, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam have decreased tariffs on 98.86% of their lines to the 0-5% tariff range in 2010, and are projected to eliminate tariffs on these goods by 2015, with the ability to do so for a few import duty lines until 2018.[167] A recent study by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited has projected that five of the top fifteen manufacturing locations in the world will be in ASEAN by 2018. Furthermore, by 2050, ASEAN is expected to be the fourth-largest economy in the world (after the European Union, the US, and China).[167]

The AEC envisions the free flow of overseas labour. However, receiving countries may require would-be workers to take licensing examinations in those countries regardless of whether or not the worker has a professional license from their home country.[168] Singapore is a major destination for skilled migrants from other ASEAN countries, mostly from Malaysia and the Philippines. Total employment there doubled between 1992 and 2008 from 1.5 million to three million, and the number of foreign workers almost tripled, from fewer than 400,000 to nearly 1.1 million. High-skilled foreign talents (customer service, nursing, engineering, IT) earn at least several thousand US dollars a month and with a credential (usually a college degree) receive employment passes.[169] In recent years, Singapore has been slowly cutting down the number of foreign workers to challenge companies to upgrade their hiring criteria and offer more jobs to local residents.

Narrowing the Development Gap (NDG) is the framework for addressing disparities among, and within, member states where pockets of underdevelopment exist. Under NDG, ASEAN has continued to coordinate closely with other sub-regional cooperation frameworks (e.g., BIMP-EAGA, IMT-GT, GMS, Mekong programs), viewing them as "equal partners in the development of regional production and distribution networks" in the AEC, and as a platform to "mainstream social development issues in developing and implementing projects" in the context of the ASCC.[170]

The six-year Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI) Work Plans have been developed to assist Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, as well as other sub-regions to ensure quick growth. The First IAI Work Plan was implemented from 2002 to 2008. The second plan (2009-2015) supports the goals of the ASEAN Community and is composed of 182 prescribed actions, which includes studies, training programs, and policy implementation support, conducted through projects supported by older ASEAN member states, and ASEAN's Dialogue partners and external parties. The IAI Work Plan is patterned after and supports the key program areas in the three ASEAN Community Blueprints: ASPC, AEC, and ASCC. The IAI Task Force, composed of representatives of the Committee of Permanent Representatives and its working group from all member states, is in charge of providing general advice and policy guidelines and directions in the design and implementation of the plan. All member states are represented in the IAI Task Force, chaired by representatives of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam. The ASEAN Secretariat, in particular through the IAI and NDG Division, supports the implementation and management of the IAI Work Plan and coordinates activities related to sub-regional frameworks. The division works closely with the Dialogue Partners, and international agencies, to develop strategies and programs to assist in promoting and implementing IAI and NDG activities in ASEAN.[170]

ASEAN's planned integration has challenged its citizens to embrace a regional identity. It delivers a challenge to construct dynamic institutions and foster sufficient amount of social capital. The underlying assumption is that the creation of a regional identity is of special interest to ASEAN and the intent of the 2020 Vision policy document was to reassert the belief in a regional framework designed as an action plan related to human development and civic empowerment. Accordingly, these assumptions will be the basis for recommendations and strategies in developing a participatory regional identity.[171]

APAEC blueprint

Part of the work towards the ASEAN Economic Community is the integration of the energy systems of the ASEAN member states. The blueprint for this integration is provided by the ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC).[172] APAEC is managed by the ASEAN Center for Energy.

2020 ASEAN Banking Integration Framework

As trade is liberalised with the integration in 2015, the need arises for ASEAN banking institutions to accommodate and expand their services to an intra-ASEAN market. Experts, however, have already forecast a shaky economic transition, especially for smaller players in the banking and financial services industry. Two separate reports by Standard & Poor's (S&P) outline the challenges that ASEAN financial institutions face as they prepare for the 2020 banking integration.[lower-alpha 3] The reports point out that overcrowded banking sector in the Philippines is expected to feel the most pressure as the integration welcomes tighter competition with bigger and more established foreign banks.[173] As a result, there needs to be a regional expansion by countries with a small banking sector to lessen the impact of the post-integration environment. In a follow-up report, S&P recently cited the Philippines for "shoring up its network bases and building up capital ahead of the banking integration – playing defence and strengthening their domestic networks".[173]

Financial integration roadmap

The roadmap for financial integration is the latest regional initiative that aims to strengthen local self-help and support mechanisms. The roadmap's implementation would contribute to the realisation of the AEC. Adoption of a common currency, when conditions are ripe, could be the final stage of the AEC. The roadmap identifies approaches and milestones in capital market development, capital account and financial services liberalisation, and ASEAN currency cooperation. Capital market development entails promoting institutional capacity as well as the facilitation of greater cross-border collaboration, linkages, and harmonisation between capital markets. Orderly capital account liberalisation would be promoted with adequate safeguards against volatility and systemic risks. To expedite the process of financial services liberalisation, ASEAN has agreed on a positive list modality and adopted milestones to facilitate negotiations. Currency cooperation would involve the exploration of possible currency arrangements, including an ASEAN currency payment system for trade in local goods to reduce the demand for US dollars and to help promote stability of regional currencies, such as by settling intra-ASEAN trade using regional currencies.[174]

In regards to a common currency, ASEAN leaders agreed in November 1999 to create the establishment of currency swaps and repurchase agreements as a credit line against future financial shocks. In May 2000, ASEAN finance ministers agreed to plan for closer cooperation through the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI).[175] The CMI has two components, an expanded ASEAN Swap Arrangement (ASA), and a network of bilateral swap arrangements among the ASEAN Plus Three. The ASA preceded the 1997 Asian financial crisis and was originally established by the monetary authorities of the five founding member states to help meet temporary liquidity problems. The ASA now includes all ten member states with an expanded facility of US$1 billion. In recognition of the economic interdependence of East Asia, which has combined foreign exchange reserves amounting to about US$1 trillion, a network of bilateral swap arrangements and repurchase agreements among the ASEAN Plus Three has been agreed upon. The supplementary facility aims to provide temporary financing for member states with balance-of-payments difficulties. In 2009, 16 bilateral swap arrangements (BSAs) were concluded with a combined amount of about US$35.5 billion.[176] The CMI was signed on 9 December 2009 and took effect on 20 March 2014 while the amended version, the multilateralisation of CMI (CMIM), was on 17 July 2014. The CMIM is a multilateral currency swap arrangement governed by a single contractual agreement. In addition, an independent regional surveillance unit called the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) was established to monitor and analyse economies and to support the CMIM decision-making process.[176] The amendments would allow access for the auction of a crisis prevention facility. These amendments are expected to fortify CMIM as the region's financial safety net in the event of any potential or actual liquidity difficulty.[177]

During peacetime, the AMRO would conduct annual consultations with individual member economies and prepare quarterly-consolidated reports on the macroeconomic assessment of the ASEAN+3 region and individual member countries. In a time of crisis, the AMRO would prepare recommendations on any swap request based on macroeconomic analysis of a member state and monitor the use and impact of funds once an application is approved. AMRO was officially incorporated as a company limited by guarantee in Singapore on 20 April 2011. Governance of AMRO is being exercised by the executive committee (EC) and its operational direction by the Advisory Panel (AP). AMRO is currently headed by Dr Yoichi Nemoto of Japan, who is serving his second two-year term until 26 May 2016.[176][174]

Food security

Member states recognise the importance of strengthening food security to maintain stability and prosperity in the region.[178] As ASEAN moves towards AEC and beyond, food security would be an integral part of the community-building agenda.[179] Strengthened food security is even more relevant in light of potentially severe risks from climate change with agriculture and fisheries being the most affected industries.[180]

Part of the aim of ASEAN integration is to achieve food security collectively via trade in rice and maize. Trade facilitation measures and the harmonisation/equivalency of food regulation and control standards would reduce the cost of trade in food products. While specialisation and revealed comparative and competitive indices point to complementarities between trade patterns among the member states, intra-ASEAN trade in agriculture is quite small, something that integration could address.[181] The MARKET project would provide flexible and demand-driven support to the ASEAN Secretariat while bringing more private-sector and civil-society input into regional agriculture policy dialogue. By building an environment that reduces barriers to trade, ASEAN trade would increase, thereby decreasing the risk of food price crisis.[182]

Economy

The group sought economic integration by creating the AEC by the end of 2015 that established a single market.[183] The average economic growth of member states from 1989 to 2009 was between 3.8% and 7%. This was greater than the average growth of APEC, which was 2.8%.[184] The ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), established on 28 January 1992,[185] includes a Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) to promote the free flow of goods between member states.[183] ASEAN had only six members when it was signed. The new member states (Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia) have not fully met AFTA's obligations, but are officially considered part of the agreement as they were required to sign it upon entry into ASEAN, and were given longer time frames to meet AFTA's tariff reduction obligations.[186] The next steps are to create a single market and production base, a competitive economic region, a region of equitable economic development, and a region that is fully integrated into the global economy. Since 2007, ASEAN countries have gradually lowered their import duties to member states, with a target of zero import duties by 2016.[187]

ASEAN countries have many economic zones (industrial parks, eco-industrial parks, special economic zones, technology parks, and innovation districts) (see reference for comprehensive list from 2015).[188] In 2018, eight of the ASEAN members are among the world's outperforming economies, with positive long-term prospect for the region.[189] ASEAN's Secretariat projects that the regional body will grow to become the world's fourth largest economy by 2030.[190]

The ASEAN Centre for Energy publishes the ASEAN Energy Outlook every five years, analysing and promoting the integration of national energy systems across the region. The sixth edition was published in 2020.[191]

Internal market

ASEAN planned to establish a single market based upon the four freedoms by the end of 2015, with the goal of ensuring free flow of goods, services, skilled labour, and capital. The ASEAN Economic Community was formed in 2015,[192] but the group deferred about 20% of the harmonization provisions needed to create a common market and set a new deadline of 2025.[193]

Until the end of 2010, intra-ASEAN trade was still low as trade involved mainly exports to countries outside the region, with the exception of Laos and Myanmar, whose foreign trade was ASEAN-oriented.[194] In 2009, realised foreign direct investment (FDI) was US$37.9 billion and increased two-fold in 2010 to US$75.8 billion. 22% of FDI came from the European Union, followed by ASEAN countries (16%), and by Japan and the United States.

The ASEAN Framework Agreement on Trade in Services (AFAS) was adopted at the ASEAN Summit in Bangkok in December 1995.[195] Under the agreement, member states enter into successive rounds of negotiations to liberalise trade in services with the aim of submitting increasingly higher levels of commitment. ASEAN has concluded seven packages of commitments under AFAS.[196]

Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) have been agreed upon by ASEAN for eight professions: physicians, dentists, nurses, architects, engineers, accountants, surveyors, and tourism professionals. Individuals in these professions will be free to work in any ASEAN states effective 31 December 2015.[197][198][199]

In addition, six member states (Malaysia, Vietnam (2 exchanges), Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore) have collaborated on integrating their stock exchanges, which includes 70% of its transaction values with the goal to compete with international exchanges.[200]

Single market will also include the ASEAN Single Aviation Market (ASEAN-SAM), the region's aviation policy geared towards the development of a unified and single aviation market in Southeast Asia. It was proposed by the ASEAN Air Transport Working Group, supported by the ASEAN Senior Transport Officials Meeting, and endorsed by the ASEAN Transport Ministers.[201] It is expected to liberalise air travel between member states allowing ASEAN airlines to benefit directly from the growth in air travel, and also free up tourism, trade, investment, and service flows.[201][202] Since 1 December 2008, restrictions on the third and fourth freedoms of the air between capital cities of member states for air passenger services have been removed,[203] while from 1 January 2009, full liberalisation of air freight services in the region took effect.[201][202] On 1 January 2011, full liberalisation on fifth freedom traffic rights between all capital cities took effect.[204] This policy supersedes existing unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral air services agreements among member states which are inconsistent with its provisions.

Monetary union

The concept of an Asian Currency Unit (ACU) started in the middle of the 1990s, prior to the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[205] It is a proposed basket of Asian currencies, similar to the European Currency Unit, which was the precursor of the Euro. The Asian Development Bank is responsible for exploring the feasibility and construction of the basket.[205][206] Since the ACU is being considered to be a precursor to a common currency, it has a dynamic outlook of the region.[207] The overall goal of a common currency is to contribute to the financial stability of a regional economy, including price stability. It means lower cost of cross-border business through the elimination of currency risk. Greater flows of intra-trade would put pressure on prices, resulting in cheaper goods and services. Individuals benefit not only from the lowering of prices, they save by not having to change money when travelling, by being able to compare prices more readily, and by the reduced cost of transferring money across borders.

However, there are conditions for a common currency: the intensity of intra-regional trade and the convergence of macroeconomic conditions. Substantial intra-ASEAN trade (which is growing, partly as a result of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and the ASEAN Economic Community.) and economic integration is an incentive for a monetary union. Member states currently trade more with other countries (80%) than among themselves (20%). Therefore, their economies are more concerned about currency stability against major international currencies, like the US dollar. On macroeconomic conditions, member states have different levels of economic development, capacity, and priorities that translate into different levels of interest and readiness. Monetary integration, however, implies less control over national monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. Therefore, greater convergence in macroeconomic conditions is being enacted to improve conditions and confidence in a common currency.[174] Other concerns include weaknesses in the financial sectors, inadequacy of regional-level resource pooling mechanisms and institutions required to form and manage a currency union, and lack of political preconditions for monetary co-operation and a common currency.[208]

Free trade

In 1992, the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) scheme was adopted as a schedule for phasing out tariffs to increase the "region's competitive advantage as a production base geared for the world market". This law would act as the framework for the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), which is an agreement by member states concerning local manufacturing in ASEAN. It was signed on 28 January 1992 in Singapore.[185]

Free trade initiatives in ASEAN are spearheaded by the implementation of the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) and the Agreement on Customs. These agreements are supported by several sector bodies to plan and to execute free trade measures, guided by the provisions and the requirements of ATIGA and the Agreement on Customs. They form a backbone for achieving targets of the AEC Blueprint and establishing the ASEAN Economic Community by the end of 2015.[209]

On 26 August 2007, ASEAN stated its aim of completing free trade agreements (FTA) with China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand by 2013, which is in line with the start of the ASEAN Economic Community by 2015.[210][211] In November 2007, ASEAN states signed the ASEAN Charter, a constitution governing relations among member states and establishing the group itself as an international legal entity.[212] During the same year, the Cebu Declaration on East Asian Energy Security was signed by ASEAN and the other members of the EAS (Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea), which pursues energy security by finding energy alternatives to fossil fuels.[213]

On 27 February 2009, an FTA with Australia and New Zealand was signed. It is believed that this FTA would boost combined GDP across the 12 countries by more than US$48 billion over the period between 2000 and 2020.[214][215] The agreement with China created the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), which went into full effect on 1 January 2010. In addition, ASEAN was noted to be negotiating an FTA with the European Union.[216] Bilateral trade with India crossed the US$70 billion target in 2012 (target was to reach the level by 2015).[217] Taiwan has also expressed interest in an agreement with ASEAN but needs to overcome diplomatic objections from China.[218]

ASEAN, together with its six major trading partners (Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea), began the first round of negotiations on 26–28 February 2013, in Bali, Indonesia on the establishment of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP),[219] which is an extension of ASEAN Plus Three and Six that covers 45% of the world's population and about a third of the world's total GDP.[220][221][222]

In 2017, ASEAN and Canada initiated exploratory discussions for an ASEAN-Canada free trade agreement.[223][224]

In 2019, Reuters highlighted a mechanism used by traders to avoid the 70% tariff on ethanol imported into China from the United States, involving importing the fuel into Malaysia, mixing it with at least 40% ASEAN-produced fuel, and re-exporting it to China tariff-free under ACFTA rules.[225]

Electricity trade

Cross-border electricity trade in ASEAN has been limited, despite efforts since 1997 to establish an ASEAN Power Grid and associated trade. Electricity trade accounts for only about 5% of the generation, whereas trades in coal and gas are 86% and 53% respectively.[226][227]

Tourism

With the institutionalisation of visa-free travel between ASEAN member states, intra-ASEAN travel has escalated. In 2010, 47% or 34 million out of 73 million tourists in ASEAN member-states were from other ASEAN countries.[228] Cooperation in tourism was formalised in 1976, following the formation of the Sub-Committee on Tourism (SCOT) under the ASEAN Committee on Trade and Tourism. The 1st ASEAN Tourism Forum was held on 18–26 October 1981 in Kuala Lumpur. In 1986, ASEAN Promotional Chapters for Tourism (APCT) were established in Hong Kong, West Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia/New Zealand, Japan, and North America.[229]

Tourism has been one of the key growth sectors in ASEAN and has proven resilient amid global economic challenges. The wide array of tourist attractions across the region drew 109 million tourists to ASEAN in 2015, up by 34% compared to 81 million tourists in 2011. As of 2012, tourism was estimated to account for 4.6% of ASEAN GDP—10.9% when taking into account all indirect contributions. It directly employed 9.3 million people, or 3.2% of total employment, and indirectly supported some 25 million jobs.[230][231] In addition, the sector accounted for an estimated 8% of total capital investment in the region.[232] In January 2012, ASEAN tourism ministers called for the development of a marketing strategy. The strategy represents the consensus of ASEAN National Tourism Organisations (NTOs) on marketing directions for ASEAN moving forward to 2015.[233] In the 2013 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) report, Singapore placed 1st, Malaysia placed 8th, Thailand placed 9th, Indonesia placed 12th, Brunei placed 13th, Vietnam placed 16th, Philippines placed 17th, and Cambodia placed 20th as the top destinations of travellers in the Asia Pacific region.[234]

1981 The ASEAN Tourism Forum (ATF) was established. It is a regional meeting of NGOs, Ministers, sellers, buyers and journalists to promote the ASEAN countries as a single one tourist destination. The annual event 2019 in Ha Long marks the 38th anniversary and involves all the tourism industry sectors of the 10 member states of ASEAN: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. It was organized by TTG Events from Singapore.

ASEAN Tourism Forum 2019 - Traditional Vietnam woman cloth parade

ASEAN Tourism Forum 2019 - Traditional Vietnam woman cloth parade ASEAN Tourism Awards 2019 - Gzhel costumes Vietnam style

ASEAN Tourism Awards 2019 - Gzhel costumes Vietnam style Nguyễn Ngọc Thiện, Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Vietnam at the ASEAN Tourism Awards 2019 in Ha Long Bay

Nguyễn Ngọc Thiện, Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Vietnam at the ASEAN Tourism Awards 2019 in Ha Long Bay Children from Thai Hai Reserve Area of Ecological Houses-on-stilts Ethnic Village at the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2019 in Ha Long Bay, Viet Nam; organised by TTG Events,

Children from Thai Hai Reserve Area of Ecological Houses-on-stilts Ethnic Village at the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2019 in Ha Long Bay, Viet Nam; organised by TTG Events, Closing Ceremony of Visit Vietnam Year 2018 & Gala Celebrating the Success of ATF 2019

Closing Ceremony of Visit Vietnam Year 2018 & Gala Celebrating the Success of ATF 2019

Foreign relations

ASEAN maintains a global network of alliances, dialogue partners and diplomatic missions, and is involved in numerous international affairs.[16][17][18][19] The organisation maintains good relationships on an international scale, particularly towards Asia-Pacific nations, and upholds itself as a neutral party in politics. It holds ASEAN Summits, where heads of government of each member states meet to discuss and resolve regional issues, as well as to conduct other meetings with countries outside the bloc to promote external relations and deal with international affairs. The first summit was held in Bali in 1976. The third summit was in Manila in 1987, and during this meeting, it was decided that the leaders would meet every five years.[235] The fourth meeting was held in Singapore in 1992 where the leaders decided to meet more frequently, every three years.[235] In 2001, it was decided that the organisation will meet annually to address urgent issues affecting the region. In December 2008, the ASEAN Charter came into force and with it, the ASEAN Summit will be held twice a year. The formal summit meets for three days, and usually includes internal organisation meeting, a conference with foreign ministers of the ASEAN Regional Forum, an ASEAN Plus Three meeting and ASEAN-CER, a meeting of member states with Australia and New Zealand.[236]

ASEAN is a major partner of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, developing cooperation model with the organisation in the field of security, economy, finance, tourism, culture, environmental protection, development and sustainability.[237][238][239][240] Additionally, the grouping has been closely aligned with China, cooperating across numerous areas, including economy, security, education, culture, technology, agriculture, human resource, society, development, investment, energy, transport, public health, tourism, media, environment, and sustainability.[241][242][243] It is also the linchpin in the foreign policy of Australia and New Zealand, with the three sides being integrated into an essential alliance.[244][245][246][247][248]

ASEAN also participates in the East Asia Summit (EAS), a pan-Asian forum held annually by the leaders of eighteen countries in the East Asian region, with ASEAN in a leadership position. Initially, membership included all member states of ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand, but was expanded to include the United States and Russia at the Sixth EAS in 2011. The first summit was held in Kuala Lumpur on 14 December 2005, and subsequent meetings have been held after the annual ASEAN Leaders' Meeting. The summit has discussed issues including trade, energy, and security and the summit has a role in regional community building.

Other meetings include the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting[249][250] that focus mostly on specific topics, such as defence or the environment,[251] and are attended by ministers. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), which met for the first time in 1994, fosters dialogue and consultation, and to promote confidence-building and preventive diplomacy in the region.[252] As of July 2007, it consists of twenty-seven participants that include all ASEAN member states, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, China, the EU, India, Japan, North and South Korea, Mongolia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Russia, East Timor, the United States, and Sri Lanka.[253] Taiwan has been excluded since the establishment of the ARF, and issues regarding the Taiwan Strait are neither discussed at ARF meetings nor stated in the ARF Chairman's Statements.

ASEAN also holds meetings with Europe during the Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM), an informal dialogue process initiated in 1996 with the intention of strengthening co-operation between the countries of Europe and Asia, especially members of the European Union and ASEAN in particular.[254] ASEAN, represented by its secretariat, is one of the forty-five ASEM partners. It also appoints a representative to sit on the governing board of Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF), a socio-cultural organisation associated with the meeting. Annual bilateral meetings between ASEAN and India, Russia and the United States are also held.

Relations with other blocs

ASEAN Plus Three

In 1990, Malaysia proposed the creation of an East Asia Economic Caucus[255] composed of the members of ASEAN, China, Japan, and South Korea. It intended to counterbalance the growing US influence in Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and Asia as a whole.[256][257] However, the proposal failed because of strong opposition from the US and Japan.[256][258] Work for further integration continued, and the ASEAN Plus Three,[259] consisting of ASEAN, China, Japan, and South Korea, was created in 1997.

ASEAN Plus Three[259] is a forum that functions as a coordinator of co-operation between the ASEAN and the three East Asian nations of China, South Korea, and Japan. Government leaders, ministers, and senior officials from the ten members of the ASEAN and the three East Asian states consult on an increasing range of issues.[260] The ASEAN Plus Three is the latest development of Southeast Asia-East Asia regional co-operation. In the past, proposals, such as South Korea's call for an Asian Common Market in 1970 and Japan's 1988 suggestion for an Asian Network, have been made to bring closer regional co-operation.[261]

The first leaders' meetings were held in 1996, and 1997 to deal with Asia–Europe Meeting issues, and China and Japan each wanted regular summit meetings with ASEAN members afterwards. The group's significance and importance were strengthened by the Asian Financial Crisis. In response to the crisis, ASEAN closely cooperated with China, South Korea, and Japan. Since the implementation of the Joint Statement on East Asia Cooperation in 1999 at the Manila Summit, ASEAN Plus Three finance ministers have been holding periodic consultations.[262] ASEAN Plus Three, in establishing the Chiang Mai Initiative, has been credited as forming the basis for financial stability in Asia,[263] the lack of such stability having contributed to the Asian Financial Crisis.

Since the process began in 1997, ASEAN Plus Three has also focused on subjects other than finance such as the areas of food and energy security, financial co-operation, trade facilitation, disaster management, people-to-people contacts, narrowing the development gap, rural development, and poverty alleviation, human trafficking, labour movement, communicable diseases, environment and sustainable development, and transnational crime, including counter-terrorism. With the aim of further strengthening the nations' co-operation, East Asia Vision Group (EAVG) II was established at the 13th ASEAN Plus Three Summit on 29 October 2010 in Hanoi to stock-take, review, and identify the future direction of the co-operation.

ASEAN Plus Six

ASEAN Plus Three was the first of attempts for further integration to improve existing ties of Southeast Asia with East Asian countries of China, Japan and South Korea. This was followed by the even larger East Asia Summit (EAS), which included ASEAN Plus Three as well as India, Australia, and New Zealand. This group acted as a prerequisite for the planned East Asia Community which was supposedly patterned after the European Community (now transformed into the European Union). The ASEAN Eminent Persons Group was created to study this policy's possible successes and failures.

The group became ASEAN Plus Six with Australia, New Zealand, and India, and stands as the linchpin of Asia Pacific's economic, political, security, socio-cultural architecture, as well as the global economy.[264][265][266][267] Codification of the relations between these countries has seen progress through the development of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free-trade agreement involving the 15 countries of ASEAN Plus Six (excluding India). RCEP would, in part, allow the members to protect local sectors and give more time to comply with the aim for developed country members.[268]

The economies in this region that have not joined the RCEP are: Hong Kong, India, Macau, North Korea and Taiwan.

Hong Kong is actively seeking to join. Hong Kong itself has signed free trade agreements with ASEAN, New Zealand, Mainland China, and Australia. Mainland China welcomes Hong Kong's participation. According to the 2018 policy address of the Special Chief Executive, the Special Chief Executive She will start negotiations with RCEP member states after the signing of RCEP. As Asia's financial center and Asia's trading hub, Hong Kong can provide member countries with high-quality financial services.

India temporarily does not join the RCEP for the protection of its own market, but Japan, China, and ASEAN welcomes India's participation.[269] The members stated that "the door will always be open" and promised to create convenient conditions for India to participate in RCEP. And India itself has signed free trade agreements with ASEAN, Japan and South Korea.

As a free trade port, Macau's tax rate itself is very low. Macau's economy does not depend on import and export trade. Tourism and gaming are the main economic industries in Macau. The Macau government did not state whether to join RCEP. Macau still has room for openness in the service industry.

Taiwan has been excluded from participating with the organization owing to China's influence on the Asia Pacific through its economic and diplomatic influence.[270] Because Taiwan itself has a New Southbound Policy, the inability to join the RCEP is expected to have little impact on Taiwan. At the same time, Taiwan is also considering whether to cancel ECFA to counter China.

Environment

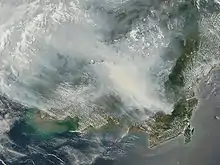

At the turn of the 21st century, ASEAN began to discuss environmental agreements. These included the signing of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution in 2002 as an attempt to control haze pollution in Southeast Asia, arguably the region's most high-profile environmental issue.[271] Unfortunately, this was unsuccessful due to the outbreaks of haze in 2005, 2006, 2009, 2013, and 2015. As of 2015, thirteen years after signing the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, the situation with respect to the long term issue of Southeast Asian haze has not been changed for 50% of the ASEAN member states, and still remains as a crisis every two years during summer and fall.[272][273][274]

Trash dumping from foreign countries (such as Japan and Canada) to ASEAN has yet to be discussed and resolved.[275] Important issues include deforestation (with Indonesia recorded the largest loss of forest in the region, more than other member states combined in the 2001-2013 period[276]), plastic waste dumping (5 member states were among the top 10 out of 192 countries based on 2010 data, with Indonesia ranked as second worst polluter[277]), threatened mammal species (Indonesia ranked the worst in the region with 184 species under threat[278]), threatened fish species (Indonesia ranked the worst in the region[279]), threatened (higher) plant species (Malaysia ranked the worst in the region[280]).

ASEAN's aggregate economy is one of the fastest growing in the world. It is expected to grow by 4.6% in 2019, and 4.8% in 2020, but at the cost of the release about 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere every year. That makes ASEAN a greater source of greenhouse gas emissions than Japan (1.3 billion tonnes per year) or Germany (796 million tonnes per year). It is the only region in the world where coal is expected to increase its share of the energy mix.[172] According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), "Since 2000 [ASEAN's] overall energy demand has grown by more than 80% and the lion's share of this growth has been met by a doubling in fossil fuel use,... Oil is the largest element in the regional energy mix and coal, largely for power generation, has been the fastest growing."[190] ASEAN has been criticized for not doing enough to mitigate climate change although it is the world's most vulnerable region in terms of climate impact.[172]

ASEAN has many opportunities for renewable energy.[281][282] With solar and wind power plus off river pumped hydro storage, ASEAN electricity industry could achieve very high penetration (78%–97%) of domestic solar and wind energy resources at a competitive levelised costs of electricity range from 55 to 115 U.S. dollars per megawatt-hour based on 2020 technology costs.[281] Vietnam's experience in solar and wind power development provides relevant implications for the other ASEAN countries.[282]

Education

To enhance the region's status in education, ASEAN education ministers have agreed four priorities for education at all levels, promoting ASEAN awareness among ASEAN citizens, particularly youth, strengthening ASEAN identity through education, building ASEAN human resources in the field of education strengthening the ASEAN University Network.[283] At the 11th ASEAN Summit in December 2005, leaders set new direction for regional education collaboration when they welcomed the decision of the ASEAN education ministers to convene meetings on a regular basis. The annual ASEAN Education Ministers Meeting oversees co-operation efforts on education at the ministerial level. With regard to implementation, programs, and activities are carried out by the ASEAN Senior Officials on Education (SOM-ED). SOM-ED also manages co-operation on higher education through the ASEAN University Network (AUN).[284] It is a consortium of Southeast Asian tertiary institutions of which 30 currently belong as participating universities.[285] Founded in November 1995 by 11 universities,[286] the AUN was established to:[283] promote co-operation among ASEAN scholars, academics, and scientists, develop academic and professional human resources, promote information dissemination among the ASEAN academic community, enhance awareness of a regional identity and the sense of "ASEAN-ness" among member states.

The Southeast Asia Engineering Education Development Network (SEED-Net) Project was established as an autonomous sub-network of AUN in April 2001. It is aimed at promoting human resource development in engineering. The network consists of 26 member institutions selected by higher education ministries of each ASEAN member state, and 11 supporting Japanese universities selected by the Japanese government. This network is mainly supported by the Japanese government through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and partially supported by the ASEAN Foundation. SEED-Net activities are implemented by the SEED-Net secretariat with the support of the JICA Project for SEED-Net now based at Chulalongkorn University.

ASEAN also has a scholarship program offered by Singapore to the 9 other member states for secondary school, junior college, and university education. It covers accommodation, food, medical benefits and accident insurance, school fees, and examination fees. Its recipients, who perform well on the GCE Advanced Level Examination, may apply for ASEAN undergraduate scholarships, which are tailored specifically to undergraduate institutions in Singapore and other ASEAN member countries.[287][288]

'Australia for ASEAN' scholarships are also offered by the Australian Government to the 'next generation of leaders' from ASEAN member states. By undertaking a Master's degree, recipients are to develop the skills and knowledge to drive change, help build links with Australia, and also participate in the Indo-Pacific Emerging Leaders Program to help develop the ASEAN Outlook for the Indo-Pacific. Each ASEAN member state is able to receive ten 'Australia for ASEAN' scholarships.[289]

Culture

The organization hosts cultural activities in an attempt to further integrate the region. These include sports and educational activities as well as writing awards. Examples of these include the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity, ASEAN Heritage Parks[290] and the ASEAN Outstanding Scientist and Technologist Award. In addition, the ASEAN region has been recognized as one of the world's most diverse regions ethnically, religiously and linguistically.[291][292]

Media

Member states have promoted co-operation in information to help build an ASEAN identity. One of the main bodies in ASEAN co-operation in information is the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information (COCI). Established in 1978, its mission is to promote effective co-operation in the fields of information, as well as culture, through its various projects and activities. It includes representatives from national institutions like the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministries of Culture and Information, national radio and television networks, museums, archives and libraries, among others. Together, they meet once a year to formulate and agree on projects to fulfil their mission.[293] On 14 November 2014, foreign ministers of member states launched the ASEAN Communication Master Plan (ACPM).[294] It provides a framework for communicating the character, structure, and overall vision of ASEAN and the ASEAN community to key audiences within the region and globally.[295] The plan seeks to demonstrate the relevance and benefits of the ASEAN through fact-based and compelling communications, recognising that the ASEAN community is unique and different from other country integration models.

ASEAN Media Cooperation (AMC) sets digital television standards and policies in preparation for broadcasters to transition from analogue to digital broadcasting. This collaboration was conceptualised during the 11th ASEAN Ministers Responsible for Information (AMRI) Conference in Malaysia on 1 March 2012 where a consensus declared that both new and traditional media were keys to connecting ASEAN peoples and bridging cultural gaps in the region.[296] Several key initiatives under the AMC include:[297]

- The ASEAN Media Portal[298] was launched 16 November 2007. The portal aims to provide a one-stop site that contains documentaries, games, music videos, and multimedia clips on the culture, arts, and heritage of the ASEAN countries to showcase ASEAN culture and the capabilities of its media industry.

- The ASEAN NewsMaker Project, an initiative launched in 2009, trains students and teachers to produce informational video clips about their countries. The project was initiated by Singapore. Students trained in NewsMaker software, video production, together with developing narrative storytelling skills. Dr Soeung Rathchavy, Deputy Secretary-General of ASEAN for ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community noted that: "Raising ASEAN awareness amongst the youth is part and parcel of our efforts to build the ASEAN Community by 2015. Using ICT and the media, our youths in the region will get to know ASEAN better, deepening their understanding and appreciation of the cultures, social traditions and values in ASEAN."[299]