Loire

The Loire (/lwɑːr/, also US: /luˈɑːr/; French pronunciation: [lwaʁ] (![]() listen); Occitan: Léger, Occitan pronunciation: [ˈled͡ʒe]; Latin: Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world.[4] With a length of 1,006 kilometres (625 mi),[2] it drains 117,054 km2 (45,195 sq mi), more than a fifth of France's land,[1] while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

listen); Occitan: Léger, Occitan pronunciation: [ˈled͡ʒe]; Latin: Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world.[4] With a length of 1,006 kilometres (625 mi),[2] it drains 117,054 km2 (45,195 sq mi), more than a fifth of France's land,[1] while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

| Loire | |

|---|---|

The Loire in Maine-et-Loire | |

Map of France with the Loire highlighted | |

| Native name | |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Massif Central |

| • location | Sainte-Eulalie, Ardèche |

| • coordinates | 44°49′48″N 4°13′20″E |

| • elevation | 1,408 m (4,619 ft)[1] |

| Mouth | Atlantic Ocean |

• location | Saint-Nazaire, Loire-Atlantique |

• coordinates | 47°16′09″N 2°11′09″W |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 1,006 km (625 mi)[2] |

| Basin size | 117,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Montjean-sur-Loire[3] |

| • average | 835.3 m3/s (29,500 cu ft/s)[3] |

| • minimum | 60 m3/s (2,100 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 4,150 m3/s (147,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Allier, Cher, Indre, Vienne, Sèvre Nantaise |

| • right | Maine, Nièvre, Erdre |

| Official name | The Loire Valley between Sully-sur-Loire and Chalonnes |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(ii)(iv) |

| Reference | 933bis |

| Inscription | 2000 (24th Session) |

| Extensions | 2017 |

| Area | 86,021 ha (212,560 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 213,481 ha (527,520 acres) |

It rises in the southeastern quarter of the French Massif Central in the Cévennes range (in the department of Ardèche) at 1,350 m (4,430 ft) near Mont Gerbier de Jonc; it flows north through Nevers to Orléans, then west through Tours and Nantes until it reaches the Bay of Biscay (Atlantic Ocean) at Saint-Nazaire. Its main tributaries include the rivers Nièvre, Maine and the Erdre on its right bank, and the rivers Allier, Cher, Indre, Vienne, and the Sèvre Nantaise on the left bank.

The Loire gives its name to six departments: Loire, Haute-Loire, Loire-Atlantique, Indre-et-Loire, Maine-et-Loire, and Saône-et-Loire. The lower-central swathe of its valley straddling the Pays de la Loire and Centre-Val de Loire regions was added to the World Heritage Sites list of UNESCO on December 2, 2000. Vineyards and châteaux are found along the banks of the river throughout this section and are a major tourist attraction.

The human history of the Loire river valley is thought by some to begin with the Middle Palaeolithic period of 90–40 kya (thousand years ago), followed by modern humans (about 30 kya), succeeded by the Neolithic period (6,000 to 4,500 BC), all of the recent Stone Age in Europe. Then came the Gauls, the local tribes during the Iron Age period of 1500 to 500 BC. They used the Loire as a key trading route by 600 BC, using pack horses to link its trade, such as the metals of the Armorican Massif, with Phoenicia and Ancient Greece via Lyon on the Rhône. Gallic rule ended in the valley in 56 BC when Julius Caesar conquered the adjacent provinces for Rome. Christianity was introduced into this valley from the 3rd century AD, as missionaries (many later recognized as saints), converted the pagans. In this period, settlers established vineyards and began producing wines.[5]

The Loire Valley has been called the "Garden of France" and is studded with over a thousand châteaux, each with distinct architectural embellishments covering a wide range of variations,[6] from the early medieval to the late Renaissance periods.[5] They were originally created as feudal strongholds, over centuries past, in the strategic divide between southern and northern France; now many are privately owned.[7]

Etymology

The name "Loire" comes from Latin Liger,[8] which is itself a transcription of the native Gaulish (Celtic) name of the river. The Gaulish name comes from the Gaulish word liga, which means "silt, sediment, deposit, alluvium", a word that gave French lie, as in sur lie, which in turn gave English lees.

Liga comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *legʰ-, meaning "to lie, lay" as in the Welsh word Lleyg, and also which gave many words in English, such as to lie, to lay, ledge, law, etc.

Geography

The source of the river lies in the eastern Massif Central, in springs to the south side of Mont Gerbier de Jonc at 44°50′38″N 4°13′12″E.[4][9] This lies in the north-eastern part of the southern Cévennes highlands, in the Ardèche commune of Sainte-Eulalie of southeastern France. It is originally a mere trickle of water located at 1,408 m (4,619 ft) above sea-level.[1] The presence of an aquifer under Mont Gerbier de Jonc gives rise to multiple sources, three of them located at the foot of Mount have been highlighted as river sources. The three streams converge to form the Loire, which descends the valley south of Mount through the village of Sainte-Eulalie itself.

.jpg.webp)

The Loire changed its course, due to tectonic deformations, from the original outfall into the English Channel to its new outfall into the Atlantic Ocean thereby forming today's narrow terrain of gorges, the Loire Valley with alluvium formations and the long stretch of beaches along the Atlantic Ocean.[1] The river can be divided into three main zones:[1]

- the Upper Loire, the area from the source to the confluence with the Allier

- the middle Loire Valley, the area from the Allier to the confluence with the Maine, about 280 km (170 mi)

- the Lower Loire, the area from Maine to the estuary

In the upper basin the river flows through a narrow, incised valley, marked by gorges and forests on the edges and a distinct low population.[1] In the intermediate section, the alluvial plain broadens and the river meanders and forks into multiple channels. River flow is particularly high in the river area near Roanne and Vichy up to the confluence with the Allier.[1] In the middle section of the river in the Loire Valley, numerous dikes built between the 12th and 19th century exist, providing mitigation against flooding. In this section the river is relatively straight, except for the area near Orléans, and numerous sand banks and islands exist.[1] The lower course of the river is characterized by wetlands and fens, which are of major importance to conservation, given that they form unique habitats for migratory birds.[1]

.jpg.webp)

The Loire flows roughly northward through Roanne and Nevers to Orléans and thereafter westward through Tours to Nantes, where it forms an estuary. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean at 47°16′44″N 2°10′19″W between Saint-Nazaire and Saint-Brevin-les-Pins, connected by a bridge over the river near its mouth. Several départements of France were named after the Loire. The Loire flows through the following départements and towns:

- Ardèche

- Haute-Loire

- Le Puy-en-Velay

- Loire

- Feurs

- Roanne

- Saône-et-Loire

- Digoin

- Allier

- Nièvre

- Decize

- Nevers

- La Charité-sur-Loire

- Cosne-Cours-sur-Loire

- Cher

- Sancerre

- Loiret

- Briare

- Gien

- Orléans

- Loir-et-Cher

- Indre-et-Loire

- Amboise

- Tours

- Maine-et-Loire:

- Montsoreau

- Saumur

- Loire-Atlantique

- Ancenis

- Nantes

- Saint-Nazaire

The Loire Valley in the Loire river basin, is a 300 km (190 mi) stretch in the western reach of the river starting with Orléans and terminating at Nantes, 56 km (35 mi) short of the Loire estuary and the Atlantic Ocean. The tidal stretch of the river extends to a length of 60 km (37 mi) and a width of 3 km (1.9 mi), which has oil refineries, the port of Saint-Nazaire and 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) of wetland whose formation is dated to 7500 BC (caused by inundation by sea waters on the northern bank of the estuary), and the beaches of Le Croisic and La Baule along the coastline.[10]

Tributaries

Its main tributaries include the rivers Maine, Nièvre and the Erdre on its right bank, and the rivers Allier, Cher, Indre, Vienne, and the Sèvre Nantaise on the left bank. The largest tributary of the river is the Allier, 410 km (250 mi) in length, which joins the Loire near the town of Nevers at 46°57′34″N 3°4′44″E.[1][4] Downstream of Nevers lies the Loire Valley, a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its fine assortment of castles. The second-longest tributary, the 372 km (231 mi) Vienne, joins the Loire at Candes-Saint-Martin at 47°12′45″N 0°4′31″E, followed by the 367.5 km (228.4 mi) Cher, which joins the Loire near Cinq-Mars-la-Pile at 47°20′33″N 0°28′49″E and the 287 km (178 mi) Indre, which joins the Loire near Néman at 47°14′2″N 0°11′0″E.[1]

- Acheneau (in Le Pellerin)

- Sèvre Nantaise (in Nantes)

- Erdre (in Nantes)

- Èvre (in Le Marillais)

- Layon (in Chalonnes-sur-Loire)

- Maine (near Angers)

- Mayenne (near Angers)

- Oudon (in Le Lion-d'Angers)

- Verzée (in Segré)

- Ernée (in Saint-Jean-sur-Mayenne)

- Oudon (in Le Lion-d'Angers)

- Sarthe (near Angers)

- Loir (north of Angers)

- Braye (in Pont-de-Braye)

- Aigre (near Cloyes-sur-le-Loir)

- Yerre (near Cloyes-sur-le-Loir)

- Conie (near Châteaudun)

- Ozanne (in Bonneval)

- Vaige (in Sablé-sur-Sarthe)

- Vègre (in Avoise)

- Huisne (in Le Mans)

- Loir (north of Angers)

- Mayenne (near Angers)

- Authion (in Sainte-Gemmes-sur-Loire)

- Thouet (near Saumur)

- Dive (near Saint-Just-sur-Dive)

- Losse (near Montreuil-Bellay)

- Argenton (near Saint-Martin-de-Sanzay)

- Thouaret (near Taizé)

- Cébron (near Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet)

- Palais (near Parthenay)

- Viette (near Parthenay)

- Vienne (in Montsoreau and Candes-Saint-Martin)

- Creuse (north of Châtellerault)

- Gartempe (in La Roche-Posay)

- Anglin (in Angles-sur-l'Anglin)

- Salleron (in Ingrandes)

- Benaize (in Saint-Hilaire-sur-Benaize)

- Abloux (in Prissac)

- Brame (in Darnac)

- Semme (in Droux)

- Anglin (in Angles-sur-l'Anglin)

- Petite Creuse (in Fresselines)

- Gartempe (in La Roche-Posay)

- Clain (in Châtellerault)

- Clouère (in Château-Larcher)

- Briance (in Condat-sur-Vienne)

- Taurion (in Saint-Priest-Taurion)

- Creuse (north of Châtellerault)

- Indre (east of Candes-Saint-Martin)

- Indrois (in Azay-sur-Indre)

- Cher (in Villandry)

- Sauldre (in Selles-sur-Cher)

- Rère (in Villeherviers)

- Arnon (near Vierzon)

- Théols (in Bommiers)

- Yèvre (in Vierzon)

- Auron (in Bourges)

- Airain (in Savigny-en-Septaine)

- Tardes (in Évaux-les-Bains)

- Voueize (in Chambon-sur-Voueize)

- Sauldre (in Selles-sur-Cher)

- Beuvron (in Chaumont-sur-Loire)

- Cosson (in Candé-sur-Beuvron)

- Loiret (in Orléans)

- Vauvise (in Saint-Satur)

- Allier (near Nevers)

- Sioule (in La Ferté-Hauterive)

- Bouble (in Saint-Pourçain-sur-Sioule)

- Dore (near Puy-Guillaume)

- Allagnon (near Jumeaux)

- Senouire (near Brioude)

- Ance (in Monistrol-d'Allier)

- Chapeauroux (in Saint-Christophe-d'Allier)

- Sioule (in La Ferté-Hauterive)

- Nièvre (in Nevers)

- Acolin (near Decize)

- Aron (in Decize)

- Alène (in Cercy-la-Tour)

- Besbre (near Dompierre-sur-Besbre)

- Arroux (in Digoin)

- Bourbince (in Digoin)

- Arconce (in Varenne-Saint-Germain)

- Lignon du Forez (in Feurs)

- Furan (in Andrézieux-Bouthéon)

- Ondaine (in Unieux)

- Lignon du Velay (in Monistrol-sur-Loire)

Geology

The geological formations in the Loire river basin can be grouped into two sets of formations, namely, the basement domain and the domain of sedimentary formations. The basement domain primarily consists of metamorphic and siliceous fragmented rocks with groundwater occurring in fissures. The sedimentary domain consists of limestone and carbonaceous rocks, that, where saturated, form productive aquifers. Rock outcrops of granite or basalt also are exposed in the river bed in several stretches.[11]

The middle stretches of the river have many limestone caves which were inhabited by humans in the prehistoric era; the caves are several types of limestone formations, namely tuffeau (a porous type of chalk, not to be confused with tufa) and Falun (formed 12 million years ago). The coastal zone shows hard dark stones, granite, schist and thick soil mantle.[10]

Discharge and flood regulation

The river has a discharge rate of 863 m3/s (30,500 cu ft/s), which is an average over the period 1967–2008.[1] The discharge rate varies strongly along the river, with roughly 350 m3/s (12,000 cu ft/s) at Orléans and 900 m3/s (32,000 cu ft/s) at the mouth. It also depends strongly on the season, and the flow of only 10 m3/s (350 cu ft/s) is not uncommon in August–September near Orléans. During floods, which usually occur in February and March[12] but also in other periods,[4] the flow sometimes exceeds 2,000 m3/s (71,000 cu ft/s) for the Upper Loire and 8,000 m3/s (280,000 cu ft/s) in the Lower Loire.[12] The most serious floods occurred in 1856, 1866 and 1911. Unlike most other rivers in western Europe, there are very few dams or locks creating obstacles to its natural flow. The flow is no longer partly regulated by three dams: Grangent Dam and Villerest Dam on the Loire and Naussac Dam on the Allier. The Villerest dam, built in 1985 a few kilometres (a few miles) south of Roanne,[13] has played a key-role in preventing recent flooding. As a result, the Loire is a very popular river for boating excursions, flowing through a pastoral countryside, past limestone cliffs and historic castles. Four nuclear power plants are located on the river: Belleville, Chinon, Dampierre and Saint-Laurent.

Navigation

In 1700 the port of Nantes numbered more inland waterway craft than any other port in France, testifying to the historic importance of navigation on France’s longest river. Shallow-draught gabares and other river craft continued to transport goods into the industrial era, including coal from Saint-Étienne loaded on to barges in Orléans. However, the hazardous free-flow navigation and limited tonnages meant that railways rapidly killed off the surviving traffic from the 1850s. In 1894 a company was set up to promote improvements to the navigation from Nantes to Briare. The works were authorised in 1904 and carried out in two phases from Angers to the limit of tides at Oudon. These works, with groynes and submersible embankments, survive and contribute to the limited navigability under present-day conditions.[14] A dam across the Loire at Saint-Léger-des-Vignes provides navigable conditions to cross from the Canal du Nivernais to the Canal latéral à la Loire.

As of 2017, the following sections are navigable:

- Loire maritime: 53 km from the Atlantic Ocean at Saint-Nazaire to Nantes, no locks[15]

- Loire: 84 km from Nantes to Bouchemaine near Angers, no locks[16]

- Canal latéral à la Loire: 196 km from Briare to Digoin, parallel to the river, 36 locks[17]

- Canal de Roanne à Digoin: 56 km from Digoin to Roanne, parallel to the river, 10 locks[18]

Climate

The French language adjective ligérien is derived from the name of the Loire, as in le climat ligérien ("the climate of the Loire Valley"). The climate is considered the most pleasant of northern France, with warmer winters and, more generally, fewer extremes in temperatures, rarely exceeding 38 °C (100 °F). It is identified as temperate maritime climate, and is characterised by the lack of dry seasons and by heavy rains and snowfall in winter, especially in the upper streams.[4] The number of sunny hours per year varies between 1400 and 2200 and increases from northwest to southeast.[1]

The Loire Valley, in particular, enjoys a pleasant temperate climate. The region experiences a rainfall of 690 mm (27.2 in) along the coast and 648 mm (25.5 in) inland.[10]

Flora

The Centre region of the Loire river valley accounts for the largest forest in France, the forest of Orléans (French: Forêt d'Orléans), covering an area of 38,234 hectares (94,480 acres), and the 5,440-hectare (13,400-acre) forested park known as the "Foret de Chambord". Other vegetation in the valley, mostly under private control, consists of tree species of oak, beech and pine. In the marshy lands, ash, alder and willows are grown with duckweed providing the needed natural fertilizing effect. The Atlantic coast is home to several aquatic herbs, the important species is Salicornia, which is used as a culinary ingredient on account of its diuretic value. Greeks introduced vines. Romans introduced melons, apples, cherries, quinces and pears during the Middle Ages, apart from extracting saffron from purple crocus species in the Orléans. Reine claude (Prunus domestica italica) tree species was planted in the gardens of the Château. Asparagus was also brought from northwestern France.[19]

Wildlife

The river flows through the continental ecoregions of Massif central and Bassin Parisien south and in its Lower course partly through South Atlantic and Brittany.[1]

Plankton

With more than 100 alga species, the Loire has the highest phytoplankton diversity among French rivers. The most abundant are diatoms and green algae (about 15% by mass) which mostly occur in the lower reaches. Their total mass is low when the river flow exceeds 800 m3/s (28,000 cu ft/s) and become significant at flows of 300 m3/s (11,000 cu ft/s) or lower which occur in summer. With decreasing flow, first species which appear are single-celled diatoms such as Cyclostephanos invisitatus, C. meneghiniana, S. Hantzschii and Thalassiosira pseudonana. They are then joined by multicellular forms including Fragilaria crotonensis, Nitzschia fruticosa and Skeletonema potamos, as well as green algae which form star-shaped or prostrate colonies. Whereas the total biomass is low in the upper reaches, the biodiversity is high, with more than 250 taxa at Orléans. At high flows and in the upper reaches the fraction of the green algae decrease and the phytoplankton is dominated by diatoms. Heterotrophic bacteria are represented by cocci (49%), rods (35%), colonies (12%) and filaments (4%) with a total density of up to 1.4×1010 cells per litre.[1]

Fish

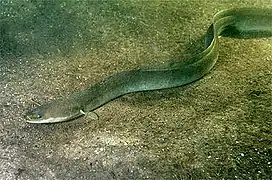

Nearly every freshwater fish species of France can be found in the Loire river basin, that is, about 57 species from 20 families. Many of them are migratory, with 11 species ascending the river for spawning. The most common species are the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), sea trout (Salmo trutta), shads (Alosa alosa and Alosa fallax), sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) European river lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis) and smelt (Osmerus eperlanus). The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is common in the upper streams, whereas the flounder (Platichtys flesus) and flathead mullet (Mugil spp.) tend to stay near the river mouth. The tributaries host brown trout (Salmo trutta), European bullhead (Cottus gobio), European brook lamprey (Lampetra planeri), zander (Sander lucioperca), nase (Chondrostoma nasus and C. toxostoma) and wels catfish (Siluris glanis). The endangered species include grayling (Thymallus thymallus), burbot (Lota lota) and bitterling (Rhodeus sericeus) and the non-native species are represented by the rock bass (Ambloplites rupestris).[1]

Although only one native fish species has become extinct in the Loire, namely the European sea sturgeon (Acipenser sturio) in the 1940s, the fish population is declining, mostly due to the decrease in the spawning areas. The latter are mostly affected by the industrial pollution, construction of dams and drainage of oxbows and swamps. The loss of spawning grounds mostly affects the pike (Esox lucius), which is the major predator of the Loire, as well as eel, carp, rudd and salmon. The great Loire salmon, a subspecies of Atlantic salmon, is regarded as the symbolic fish of the river. Its population has decreased from about 100,000 in the 19th century to below 100 in the 1990s that resulted in the adoption of a total ban of salmon fishing in the Loire basin in 1984. A salmon restoration program was initiated in the 1980s and included such as measures as removal of two obsolete hydroelectric dams and introduction of juvenile stock. As a result, the salmon population increased to about 500 in 2005.[1]

Amphibians

Most amphibians of the Loire are found in the slow flow areas near the delta, especially in the floodplain, marshes and oxbows. They are dominated by the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra), frogs and toads. The toads include Bufo bufo, Alytes obstetricans, Bombina variegata, Bufo calamita, Pelobates fuscus and Pelobates cultripes. The frogs are represented by the Parsley frog (Pelodites punctatus), European tree frog (Hyla arborea), Common Frog (Rana temporaria), Agile Frog (R. dalmatina), Edible Frog (R. esculenta), Perez's Frog (R. perezi), marsh frog (R. ridubunda) and Pool Frog (R. lessonae). Newts of the Loire include the Marbled Newt (Triturus marmoratus), Smooth Newt (T. vulgaris), Alpine Newt (T. alpestris) and Palmate Newt (T. helveticus).[1]

Avifauna

The Loire hosts about 64% of nesting bird species of France, that is 164 species, of which 54 are water birds, 44 species are common for managed forests, 41 to natural forests, 13 to open and 12 to rocky areas. This avifauna has been rather stable, at least between the 1980s and 2000s, with significant abundance variations observed only for 17 species. Of those, five species were growing in population, four declining, and other eight were fluctuating. Some of these variations had a global nature, such as the expansion of the Mediterranean gull in Europe.[1]

Conservation

The Loire has been described as "constantly under threat of losing its status as the last wild river in France".[20] The reason for this is its sheer length and possibility of extensive navigation, which severely limits the scope of river conservation.[20] The Federation, a member of the IUCN since 1970, has been very important in the campaign to save the Loire river system from development.[21]

In 1986, the French government, the Loire-Brittany Water Agency and the EPALA settled an agreement on flood prevention and water storage programme in the basin, involving construction of four large dams, one on the Loire itself and three on the Allier and Cher.[22] The French government proposed a construction of a dam at Serre de la Fare on the upper Loire which would have been an environmental catastrophe, as it would have inundated some 20 km (12 mi) of pristine gorges.[22] As a result, the WWF and other NGOs established the Loire Vivante (Living Loire) network in 1988 to oppose this and arranged an initial meeting with the French Minister of the Environment.[22] The French government initially rejected the conservation concerns and in 1989 gave the projects the green light.[22] This sparked public demonstrations by the WWF and conservation groups.[22] In 1990, Loire Vivante met with the French Prime Minister and the government, successfully, as the government demanded that the EPALA embark upon major reforms in its approach to managing the river.[22] Due to extensive lobbying, the proposal and the other dam proposals were eventually rejected in the 1990s. The gorges zone has since been protected as a ‘Natura 2000’ site under European Union environmental legislation.[22]

The WWF were particularly important in changing the perception of the French authorities in support for dam building to environmental protection and sustainable management of its river basin.[22] In 1992, they aided the ‘Loire Nature’ project, which received funds of some $US 9 million under the EU's ‘LIFE’ programme until 1999, embarking upon restoration to the river's ecosystems and wildlife.[22] That year, the Upper Loire Valley Farmers Association was also established through a partnership between SOS Loire Vivante and a farmers’ union to promote sustainable rural tourism.[22] The French government adopted the Natural Loire River Plan (Plan Loire Grandeur Nature) in January 1994, initiating the decommissioning of three dams on the river.[23] The final dam was decommissioned by Électricité de France at a cost of 7 million francs in 1998.[23] The basis of the decision was that the economic benefits of the dams did not outweigh their significant ecological impacts, so the intention was to restore the riverine ecosystems and replenish great Loire salmon stocks.[23] The Loire is unique in this respect as the Atlantic salmon can swim as far as 900 km (560 mi) up the river and spawn in the upper reaches of the Allier. The French government undertook this major plan, chiefly because pollution and overfishing had reduced approximately 100,000 salmon migrating annually to their spawning grounds in the headwaters of the Loire and its tributaries to just 67 salmon in 1996 on the upper Allier.[22]

The WWF, BirdLife International, and local conservation bodies have also made considerable efforts to improve the conservation of the Loire estuary and its surroundings, given that they are unique habitats for migrating birds. The estuary and its shoreline are also important for fishing, shellfish farming and tourism. The major commercial port at Nantes has caused severe damage to the ecosystem of the Loire estuary.[22] In 2002, the WWF aided a second Loire Nature project and expanded its scope to the entire basin, addressing some 4,500 hectares (11,000 acres) of land under a budget of US$18 million, mainly funded by government and public bodies, such as the Établissement Publique Loire (EPL), a public institution which had formerly advocated large-scale dam projects on the river.[22]

History

Prehistoric period

Studies of the palaeo-geography of the region suggest that the palaeo-Loire flowed northward and joined the Seine,[24][25] while the lower Loire found its source upstream of Orléans in the region of Gien, flowing westward along the present course. At a certain point during the long history of uplift in the Paris Basin, the lower, Atlantic Loire captured the "palaeo-Loire" or Loire séquanaise ("Seine Loire"), producing the present river. The former bed of the Loire séquanaise is occupied by the Loing.

The Loire Valley has been inhabited since the Middle Palaeolithic period from 40–90 ka.[26] Neanderthal man used stone tools to fashion boats out of tree trunks and navigated the river. Modern man inhabited the Loire valley around 30 ka.[26] By around 5000 to 4000 BC, they began clearing forests along the river edges and cultivating the lands and rearing livestock.[26] They built megaliths to worship the dead, especially from around 3500 BC. The Gauls arrived in the valley between 1500 and 500 BC, and the Carnutes settled in Cenabum in what is now Orléans and built a bridge over the river.[26] By 600 BC the Loire had already become a very important trading route between the Celts and the Greeks. A key transportation route, it served as one of the great "highways" of France for over 2000 years.[7] The Phoenicians and Greeks had used pack horses to transport goods from Lyon to the Loire to get from the Mediterranean basin to the Atlantic coast.

Ancient Rome, Alans and the Vikings

The Romans successfully subdued the Gauls in 52 BC and began developing Cenabum, which they named Aurelianis. They also began building the city of Caesarodunum, now Tours, from AD 1.[26] The Romans used the Loire as far as Roanne, around 150 km (93 mi) downriver from the source. After AD 16, the Loire river valley became part of the Roman province of Aquitania, with its capital at Avaricum.[26] From the 3rd century, Christianity spread through the river basin, and many religious figures began cultivating vineyards along the river banks.[26]

In the 5th century, the Roman Empire declined and the Franks and the Alemanni came to the area from the east. Following this there was ongoing conflict between the Franks and the Visigoths.[27] In 408, the Iranian tribe of Alans crossed the Loire and large hordes of them settled along the middle course of the Loire in Gaul under King Sangiban.[28] Many inhabitants around the present city of Orléans have names bearing witness to the Alan presence – Allaines.

In the 9th century, the Vikings began invading the west coast of France, using longships to navigate the Loire. In 853 they attacked and destroyed Tours and its famous abbey, later destroying Angers in raids of 854 and 872.[27] In 877 Charles the Bald died, marking an end to the Carolingian dynasty. After considerable conflict in the region, in 898 Foulques le Roux of Anjou gained power.[29]

.jpg.webp)

Medieval period

During the Hundred Years' War from 1337 to 1453, the Loire marked the border between the French and the English, who occupied territory to the north. One-third of the inhabitants died in the epidemic of the Black Death of 1348–9.[29] The English defeated the French in 1356 and Aquitaine came under English control in 1360. In 1429, Joan of Arc persuaded Charles VII to drive out the English from the country.[30] Her successful relief of the siege of Orléans, on the Loire, was the turning point of the war.

In 1477, the first printing press in France was established in Angers, and around this time the Chateau de Langeais and Chateau de Montsoreau were built.[31] During the reign of François I from 1515 to 1547, the Italian Renaissance had a profound influence upon the region, as people adopted its elements in the architecture and culture, particularly among the elite who expressed its principles in their chateaus.[32][33]

In the 1530s, the Reformation ideas reached the Loire valley, with some people becoming Protestant. Religious wars followed and in 1560 Catholics drowned several hundred Protestants in the river.[31][34] During the Wars of Religion from 1562 to 1598, Orléans served as a prominent stronghold for the Huguenots but in 1568, Protestants blew up Orléans Cathedral.[35][36] In 1572 some 3000 Huguenots were slaughtered in Paris in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. Hundreds more were drowned in the Loire by Catholics.[31]

1600–present

For centuries local people used wooden embankments and dredging to try to maintain a navigable channel on the river, as it was critical to transportation. River traffic increased gradually, with a toll system being used in medieval times. Today some of these toll bridges still remain, dated to over 800 years.[37] During the 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert instituted the use of stone retaining walls and quays from Roanne to Nantes, which helped make the river more reliable,[38] but navigation was still frequently stopped by excessive conditions during flood and drought. In 1707, floods were said to have drowned 50,000 people in the river valley,[39] with the water rising more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in two hours in Orléans. Typically passenger travel downriver from Orléans to Nantes took eight days, with the upstream journey against the flow taking fourteen. It was also a dumping ground for prisoners in the War in the Vendée since they thought it was a more effective way of killing.

Soon after the beginning of the 19th century, steam-driven passenger boats began to ply the river between Nantes and Orléans, making the upriver journey faster; by 1843, 70,000 passengers were being carried annually in the Lower Loire and 37,000 in the Upper Loire.[40] But competition from the railway, beginning in the 1840s, caused a decline in trade on the river. Proposals to develop a fully navigable river up to Briare came to nothing. The opening of the Canal latéral à la Loire in 1838 enabled navigation between Digoin and Briare to continue,[41] but the river level crossing at Briare remained a problem until the construction of the Briare aqueduct in 1896. At 662.69 metres (2,174.2 ft), this was the longest such structure in the world for quite some time.[41]

The Canal de Roanne à Digoin was also opened in 1838. It was nearly closed in 1971 but, in the early 21st century, it still provides navigation further up the Loire valley to Digoin.[41][42] The 261 km (162 mi) Canal de Berry, a narrow canal with locks only 2.7 m (8.9 ft) wide, which was opened in the 1820s and connected the Canal latéral à la Loire at Marseilles-lès-Aubigny to the river Cher at Noyers and back into the Loire near Tours, was closed in 1955.

The river is officially navigable as far as Bouchemaine,[43] where the Maine joins it near Angers. Another short stretch much further upstream at Decize is also navigable, where a river level crossing from the Canal latéral à la Loire connects to the Canal du Nivernais.

In 2022, a drought rendered parts of the Loire unnavigable for fish and water vessels as they were partially or completely dried up.[44]

Timeline

The monarchy of France ruled in the Loire Valley for several centuries, giving it the name of "The Valley of Kings". These rulers started with the Gauls, followed by the Romans, and the Frankish dynasty. They were succeeded by the kings of France, who ruled from the late 14th century till the French Revolution; together these rulers contributed to the development of the valley. The chronology of the rulers is presented; in the table below.[5]

| Ruler | Period of reign | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Gauls | 1500–500 BC | Iron Age. Settled in Cenabum (Orléans) and Arabou. Trading along the Loire |

| Romans | 52 BC-5th century | Spread of Christianity among communities living along the Loire river banks and Benedictine Order prospered. |

| Frankish Dynasty and feudal lords | 5th–10th centuries | Power struggles among feudal states. Charles Martel defeated Moors at Poitiers preventing Muslim incursions. Attila, leader of Huns was stopped from entering the Orléans city. |

| Jean II | 1350–1364 | Was defeated by England. Ceded territory to the English Crown |

| Charles VI | 1380–1422 | Ruled during the peak of Hundred Years' War. Was known as the mad king or ‘le fou’. Married his daughter to Henry V, the King of England, and who was also declared heir to the throne of France. |

| Charles VII | 1422–1461 | He was helped by the famous Joan of Arc to ascend the throne of France and ruled from Chinon. He also had an officially recognized mistress named Agnès Sorel. |

| Louis XI | 1461–1483 | An authoritarian ruler, reigned from Amboise, and had two queens |

| Charles VIII | 1483–1498 | He had strange marriages, including Anne, a four-year-old bride who married the heir of Charles VIII after his death. |

| Louis XII | 1498–1515 | Married widow Anne de Bretagne after divorcing Jeanne de Valois. Anne ruled from Blois till her death in 1514. Louis died in 1515 |

| François I | 1515–1547 | Second cousin of Louis XII. Activity centred at Amboise. Literary and architectural attainments. Influence of Renaissance architecture and scientific ideas. Secular ideas prevailed over religious ethos. Leonardo da Vinci was patronized who settled in Amboise in 1516. Captured in the war in 1525 with the Italians. |

| Reformist era, Wars of Religion | 1530–1572 | Internecine fights and killings among the Catholics, Protestants and Catholic Monarchy |

| Henri III | 1574–1589 | Fled from Louvre. Took refuge in Tours and eventually killed by a monk |

| Henri IV | 1553–1610 | First King of Bourbon dynasty, Adopted the Catholic faith, Decreed the Edict of Nantes. Saumur was established as a prominent academic centre. |

| Louis XIII | 1610– | Importance of Loire valley declined |

| French Revolution | 1789 onwards | Decline of monarchy or rule of Kings. Many châteaux of Loire valley destroyed and many converted into prisons and schools. Reign of terror between 1793 and 1794 saw killing of counter revolutionaries by sinking ships carrying them forcibly in the Loire. |

Loire Valley

The Loire Valley (French: Vallée de la Loire) lies in the middle stretch of the river, extends for about 280 km (170 mi) and comprises an area of roughly 800 km2 (310 sq mi).[1] It is also known as the Garden of France – due to the abundance of vineyards, fruit orchards, artichoke, asparagus and cherry fields which line the banks of the river[45] – and also as the "cradle of the French language". It is also noteworthy for its architectural heritage: in part for its historic towns such as Amboise, Angers, Blois, Chinon, Nantes, Orléans, Saumur, and Tours, but in particular for its castles, such as the Château d'Amboise, Château d'Angers, Château de Chambord, Château de Montsoreau, Château d'Ussé, Château de Villandry and Chenonceau, and also for its many cultural monuments, which illustrate the ideals of the Renaissance and the Age of the Enlightenment on western European thought and design.

On December 2, 2000, UNESCO added the central part of the Loire valley, between Bouchemaine in Anjou and Sully-sur-Loire in Loiret, to its list of World Heritage Sites. In choosing this area that includes the French départements of Loiret, Loir-et-Cher, Indre-et-Loire, and Maine-et-Loire, the committee said that the Loire Valley is: "an exceptional cultural landscape, of great beauty, comprised of historic cities and villages, great architectural monuments – the Châteaux – and lands that have been cultivated and shaped by centuries of interaction between local populations and their physical environment, in particular the Loire itself."

Architecture

Architectural edifices were created in Loire valley from the 10th century onwards with the defensive fortress like structures called the "keeps" or "donjons" built between 987 and 1040 by Anjou Count Foulques Nerra of Anjou (the Falcon). However, one of the oldest such structures in France is the Donjon de Foulques Nerra built in 944.[46]

This style was replaced by the religious architectural style in the 12th to 14th centuries when the impregnable château fortresses were built on top of rocky hills; one of the impressive fortresses of this type is the Château d'Angers, which has 17 gruesome towers. This was followed by aesthetically built châteaux (to also function as residential units), which substituted the quadrangular layout of the keep. However, the exterior defensive structures, in the form of portcullis and moats surrounding the thick walls of the châteaux' forts were retained.[47] There was further refinement in the design of the châteaux in the 15th century before the Baroque style came into prominence with decorative and elegantly designed interiors and which became fashionable from the 16th to the end of the 18th century.[46]

The Baroque style artists who created some of the exquisite château structures were: the Parisian, François Mansart (1598–1662) whose classical symmetrical design is seen in the Château de Blois; Jacques Bougier (1635) of Blois whose classical design is the Château de Cheverny; Guillaume Bautru remodelled the Château de Serrant (at the extreme western end of the valley). In the 17th century, there was feverish pace in the design of châteaux for introducing exotic styles; a notable structure of this period is the Pagode de Chanteloup at Amboise, which was built between 1773 and 1778.[46]

The Neoclassical architectural style, was a revival of Classical style of architecture, which emerged in the mid 18th century; one such notable structure is the Château de Menars built by Jacques Ange Gabriel (1698–1782) who was the royal architect in the court of Louis XV (1715–74). This style was perpetuated during the reign of Louis XVI (1774–92) but with more refinements; one such refined château seen close to Angers is the Château de Montgeoffroy. Furnishings inside the châteaux also witnessed changes to suit the living styles of its occupants.[48] Gardens, both ornamental fountains, footpaths flower beds and tended grass) and kitchen type (to grow vegetables), also accentuated the opulence of the châteaux.

The French Revolution (1789) brought a radical change for the worse in the scenarios for chateaus, as monarchy ended in France.[49]

Châteaux

The châteaux, numbering more than three hundred, represent a nation of builders starting with the necessary castle fortifications in the 10th century to the splendour of those built half a millennium later. When the French kings began constructing their huge châteaux here, the nobility, not wanting or even daring to be far from the seat of power, followed suit. Their presence in the lush, fertile valley began attracting the very best landscape designers. Today, these privately owned châteaux serve as homes, a few open their doors to tourist visits, while others are operated as hotels or bed and breakfasts. Many have been taken over by a local government authority or the giant structures like those at Chambord are owned and operated by the national government and are major tourist sites, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Some notable Châteaux on the Loire include Beaufort- Mareuil sur Cher – Lavoûte-Polignac – Bouthéon – Montrond – Bastie d'Urfé – Château féodal des Cornes d'Urfé – La Roche – Château féodal de Saint-Maurice-sur-Loire – Saint-Pierre-la-Noaille – Chevenon – Palais ducal de Nevers – Saint-Brisson – Gien – La Bussière – Pontchevron – La Verrerie (near Aubigny-sur-Nère) – Sully-sur-Loire – Châteauneuf-sur-Loire – Boisgibault – Meung-sur-Loire – Menars – Talcy – Château de la Ferté – Chambord – Blois – Villesavin – Cheverny – Beauregard – Troussay – Château de Chaumont – Amboise – Clos-Lucé – Langeais – Gizeux – Les Réaux – Montsoreau – Montreuil-Bellay – Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet – Saumur – Boumois – Brissac – Montgeoffroy – Plessis-Bourré – Château des Réaux

Amboise on the banks of the Loire

Amboise on the banks of the Loire Chateau de Langeais

Chateau de Langeais Château de Blois interior façades in Gothic, Renaissance and Classic styles (from right to left).

Château de Blois interior façades in Gothic, Renaissance and Classic styles (from right to left). Château de Valençay.

Château de Valençay..jpg.webp) Château de Montsoreau

Château de Montsoreau

Wine making

The Loire Valley wine region includes the French wine regions situated along the Loire from the Muscadet region near the city of Nantes on the Atlantic coast to the region of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé just southeast of the city of Orléans in north central France. In between are the regions of Anjou, Saumur, Bourgueil, Chinon, and Vouvray. The Loire Valley itself follows the river through the Loire province to the river's origins in the Cévennes but the majority of the wine production takes place in the regions noted above.

The Loire Valley has a long history of winemaking dating back to the 1st century. In the High Middle Ages, the wines of the Loire Valley were the most esteemed wines in England and France, even more prized than those from Bordeaux.[50] Archaeological evidence suggest that the Romans planted the first vineyards in the Loire Valley during their settlement of Gaul in the 1st century AD. By the 5th century, the flourishing viticulture of the area was noted in a publication by the poet Sidonius Apollinaris. In his work History of the Franks, Bishop Gregory of Tours wrote of the frequent plundering by the Bretons of the area's wine stocks. By the 11th century the wines of Sancerre had a reputation across Europe for their high quality. Historically the wineries of the Loire Valley have been small, family owned operations that do a lot of estate bottling. The mid-1990s saw an increase in the number of négociant and co-operative to where now about half of Sancerre and almost 80% of Muscadet is bottled by a négociant or co-op.[51]

The Loire river has a significant effect on the mesoclimate of the region, adding the necessary extra few degrees of temperature that allows grapes to grow when the areas to the north and south of the Loire Valley have shown to be unfavourable to viticulture. In addition to finding vineyards along the Loire, several of the river's tributaries are also well planted—including the rivers Allier, Cher, Indre, Loir, Sèvre Nantaise and Vienne.[52] The climate can be very cool with spring time frost being a potential hazard for the vines. During the harvest months rain can cause the grapes to be harvested underripe but can also aid in the development of Botrytis cinerea for the region's dessert wines.[50]

The Loire Valley has a high density of vine plantings with an average of 4,000–5,000 vines per hectare (1,600–2,000 per acre). Some Sancerre vineyards have as many as 10,000 plants per hectare. With more vines competing for the same limited resources in the soil, the density is designed to compensate for the excessive yields that some of the grape varieties, like Chenin blanc, are prone to have. In recent times, pruning and canopy management have started to limit yields more effectively.[50]

The Loire Valley is often divided into three sections. The Upper Loire includes the Sauvignon blanc dominated areas of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé. The Middle Loire is dominated by more Chenin blanc and Cabernet franc wines found in the regions around Touraine, Saumur, Chinon and Vouvray. The Lower Loire that leads to the mouth of the river's entrance to the Atlantic goes through the Muscadet region which is dominated by wines of the Melon de Bourgogne grape.[53] Spread out across the Loire Valley are 87 appellation under the AOC, VDQS and Vin de Pays systems. There are two generic designation that can be used across the whole of the Loire Valley. The Crémant de Loire which refers to any sparkling wine made according to the traditional method of Champagne. The Vin de Pays du Jardin de la France refers to any varietally labelled wine, such as Chardonnay, that is produced in the region outside of an AOC designation.[52]

The area includes 87 appellations under the Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC), Vin Délimité de Qualité Superieure (VDQS) and Vin de pays systems. While the majority of production is white wine from the Chenin blanc, Sauvignon blanc and Melon de Bourgogne grapes, there are red wines made (especially around the Chinon region) from Cabernet franc. In addition to still wines, rosé, sparkling and dessert wines are also produced. With Crémant production throughout the Loire valley, it is the second largest sparkling wine producer in France after Champagne.[54] Among these different wine styles, Loire wines tend to exhibit characteristic fruitiness with fresh, crisp flavours-especially in their youth.[52]

Art

The Loire has inspired many poets and writers, including: Charles d'Orléans, François Rabelais, René Guy Cadou, Clément Marot, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay, Jean de La Fontaine, Charles Péguy, Gaston Couté; and painters such as: Raoul Dufy, J. M. W. Turner, Gustave Courbet, Auguste Rodin, Félix Edouard Vallotton, Jacques Villon, Jean-Max Albert, Charles Leduc, Edmond Bertreux, and Jean Chabot.

Scène of the Loire, by J. M. W. Turner.

Scène of the Loire, by J. M. W. Turner. La source de la Loire, by Gustave Courbet.

La source de la Loire, by Gustave Courbet. Portrait of the Loire, by Jean-Max Albert, 1988. Musée de la Loire, Cosne-sur-Loire.

Portrait of the Loire, by Jean-Max Albert, 1988. Musée de la Loire, Cosne-sur-Loire. Les Rosiers-sur-Loire by Jean-Jacques Delusse, 1800

Les Rosiers-sur-Loire by Jean-Jacques Delusse, 1800 The Loire at Montsoreau, J. M. W. Turner, 1832, Château de Montsoreau-Museum of Contemporary Art.

The Loire at Montsoreau, J. M. W. Turner, 1832, Château de Montsoreau-Museum of Contemporary Art.

See also

- Rivers of France

- Pays de la Loire region

References

- Tockner, Klement; Uehlinger, Urs; Robinson, Christopher T. (2009). Rivers of Europe. Academic Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-12-369449-2. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Sandre. "Fiche cours d'eau - la Loire (----0000)".

- "The Loire at Montjean". River Discharge Database. Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment. 2010-02-13. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- "The Loire". Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- Nicola Williams; Virginie Boone (1 May 2002). The Loire. Lonely Planet. pp. 9–12, 14, 16–17, 19, 21–22, 24, 26, 27–36, 40–54. ISBN 978-1-86450-358-6. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "Welcome to the Loire Valley". Western France Tourist Board. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "The Loire Valley" (PDF). Lonely Planet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- Montclos, Jean-Marie Pérouse de (1997). Châteaux of the Loire Valley. Könemann. ISBN 978-3-89508-598-7. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Barbour, Philippe (1 July 2007). Rhone Alpes, 2nd. New Holland Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-86011-357-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Williams & Boone, p. 33

- Tockner, Klement; Uehlinger, Urs; Robinson, Christopher T. (2009). "5.2.1". Rivers of Europe. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-369449-2. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "Луара (река во Франции)". Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian).

- New scientist. IPC Magazines. 1991. p. 46. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Edwards-May, David (2010). Inland Waterways of France. St Ives, Cambs., UK: Imray. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-1-846230-14-1.

- Fluviacarte, Loire (maritime)

- Fluviacarte, Loire

- Fluviacarte, Canal latéral à la Loire

- Fluviacarte, Canal de Roanne à Digoin

- Williams & Boone, p. 35-36

- Boon, P. J.; Davies, Bryan Robert; Petts, Geoffrey E. (2000). Global perspectives on river conservation: science, policy, and practice. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-96062-1. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- IUCN bulletin. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 1989. p. 9. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "Loire" (PDF). Assets.panda.org, World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Vision for water and nature: a world strategy for conservation and sustainable management of water resources in the 21st century. IUCN. 1 January 2000. p. 22. ISBN 978-2-8317-0575-0. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Tourenq, J.; Pomerol, C. (1995). "Mise en évidence, par la présence d'augite du Massif Central, de l'existence d'une pré-Loire-pré-Seine coulant vers la Manche". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 320: 1163–1169.

- Antoine, Pierre; Lautridou, Jean Pierre; Laurent, Michel (June 2000). "Long-term fluvial archives in NW France: response of the rivers Seine and Somme to tectonic movements, climatic variations and sea-level changes". Geomorphology. 33 (3–4): 183–207. doi:10.1016/s0169-555x(99)00122-1.

- Williams & Boone, p.11

- Williams & Boone, p.12

- Abaev, V. I.; Bailey, H. W. "Alans". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. I/8. pp. 801–803.

- Williams & Boone, p. 14

- Bradbury, Jim (1 February 2004). Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Taylor and Francis. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-203-64466-9. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Williams & Boone, p.16

- Aa. Vv. (20 June 2007). Châteaux of the Loire. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 17. ISBN 978-88-476-1840-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Moffett, Marian; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). A world history of architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-85669-371-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Jervis, William Henley (23 February 2010). A History of France: From the Earliest Times to the Establishment of the Second Empire in 1852. BiblioLife. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-145-42193-6. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Mellersh, H. E. L.; Williams, Neville (May 1999). Chronology of world history. ABC-CLIO. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-57607-155-7. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Finney, Paul Corby (1999). Seeing beyond the Word: Visual Arts and the Calvinist Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8028-3860-5. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Smith, Judy (November 2002). Holiday walks in the Loire Valley. Sigma Leisure. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-85058-772-9. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Trout, Andrew P. (1978). Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7715-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Embleton, Clifford; Embleton-Hamann, Christine (1997). Geomorphological hazards of Europe. Elsevier. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-444-88824-2. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Braudel, Fernand; Reynolds, Sian (April 1992). Identity of France: People and Production. HarperPerennial. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-06-092142-2. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- McKnight, Hugh (September 2005). Cruising French Waterways. Sheridan House, Inc. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-57409-210-3. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Institut des études rhodaniennes (1971). Revue de géographie de Lyon. Université de Lyon. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Liley, John (6 March 1975). France, the quiet way. Stanford Maritime. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-540-07140-1. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Mahe, Stephane (17 August 2022). "France's river Loire sets new lows as drought dries up its tributaries". Loireauxence: Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Williams & Boone, p.10

- Williams & Boone, p. 19

- Williams & Boone, p. 17

- Williams & Boone, pp. 22–26

- Williams & Boone, p. 28

- J. Robinson (ed.) The Oxford Companion to Wine Third Edition, pp. 408–410, Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- MacNeil, K. (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 259–272. ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- Fallis, C., ed. (2006). The Encyclopedic Atlas of Wine. Global Book Publishing. pp. 168–176. ISBN 1-74048-050-3.

- Robinson, J. (2003). Jancis Robinson's Wine Course (3rd ed.). Abbeville Press. pp. 180–184. ISBN 0-7892-0883-0.

- Stevenson, T. (2005). The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 196–198. ISBN 0-7566-1324-8.

Bibliography

External links

- River Loire guide, places, ports and moorings on the river in the navigable length from the Maine to Saint-Nazaire, by the author of Inland Waterways of France, Imray.

- Navigation details for 80 French rivers and canals (French waterways website section)

- (in English) Tourist Office Board Loire Valley

- (in English) Waterways In Western Loire – Free Online Travel Brochure