Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon[lower-alpha 1] (born Philipp Schwartzerdt;[lower-alpha 2] 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and John Calvin as a reformer, theologian, and moulder of Protestantism.[1]

Philip Melanchthon | |

|---|---|

%252C_by_Lucas_Cranach_the_Elder_-_Gem%C3%A4ldegalerie_Alte_Meister%252C_Kassel.jpg.webp) Portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1543 | |

| Born | Philipp Schwartzerdt 16 February 1497 Bretten, Electoral Palatinate in the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany) |

| Died | 19 April 1560 (aged 63) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Years active | 16th century |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Reformation |

| Language | German |

| Tradition or movement | Lutheranism |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

Melanchthon along with Luther denounced what they believed was the exaggerated cult of the saints, asserted justification by faith, and denounced what they considered to be the coercion of the conscience in the sacrament of penance (confession and absolution), which they believed could not offer certainty of salvation. Both rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation, i.e. that the bread and wine of the eucharist are converted by the Holy Spirit into the flesh and blood of Christ; however, they affirmed that Christ's body and blood are present with the elements of bread and wine in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. This Lutheran view of sacramental union contrasts with the understanding of the Catholic Church that the bread and wine cease to be bread and wine at their consecration (while retaining the appearances of both). Melanchthon made his distinction between law and gospel the central formula for Lutheran evangelical insight. By the "law", he meant God's requirements both in Old and New Testament; the "gospel" meant the free gift of grace through faith in Jesus Christ.

Early life and education

He was born Philipp Schwartzerdt on 16 February 1497, at Bretten, where his father Georg Schwarzerdt (1459–1508) was armorer to Philip, Count Palatine of the Rhine.[2] His mother was Barbara Reuter (1476/77–1529). His birthplace, along with almost the whole city of Bretten, was burned in 1689 by French troops during the War of the Palatinate Succession. The town's Melanchthonhaus was built on its site in 1897.

In 1507 he was sent to the Latin school at Pforzheim, where the rector, Georg Simler of Wimpfen, introduced him to the Latin and Greek poets and to Aristotle. He was influenced by his great-uncle Johann Reuchlin, a Renaissance humanist; it was Reuchlin who suggested Philipp follow a custom common among humanists of the time and change his surname from "Schwartzerdt" (literally 'black earth'), into the Greek equivalent "Melanchthon" (Μελάγχθων).[3]

Philipp was only eleven when in 1508 both his grandfather (17 October) and father (27 October) died within eleven days.[4] He and a brother were brought to Pforzheim to live with his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Reuter, sister of Reuchlin.[5]

The next year he entered the University of Heidelberg, where he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and astronomy/astrology, and became known as a scholar of Greek.[6] Denied the master's degree in 1512 on the grounds of his youth, he went to Tübingen, where he continued humanistic studies but also worked on jurisprudence, mathematics, and medicine.[7] While there he was also taught the technical aspects of astrology by Johannes Stöffler.[8]

After gaining a master's degree in 1516, he began to study theology. Under the influence of Reuchlin, Erasmus, and others, he became convinced that true Christianity was something different from the scholastic theology as taught at the university. He became a conventor (repentant) in the contubernium and instructed younger scholars. He also lectured on oratory, on Virgil and on Livy.

His first publications were a number of poems in a collection edited by Jakob Wimpfeling (c. 1511),[9] the preface to Reuchlin's Epistolae clarorum virorum (1514), an edition of Terence (1516), and a Greek grammar (1518).

Professor at Wittenberg

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg from Martin Luther on the recommendation of his great-uncle, and became professor of Greek there at the age of 21. He studied the Scriptures, especially of Paul, and Evangelical doctrine. Attending the disputation of Leipzig (1519) as a spectator, he nonetheless participated with his comments. After his views were attacked by Johann Eck, Melanchthon replied based on the authority of Scripture in his Defensio contra Johannem Eckium (Wittenberg, 1519).

Following lectures on the Gospel of Matthew and the Epistle to the Romans, together with his investigations into Pauline doctrine, he was granted the degree of bachelor of theology, and transferred to the theological faculty.[10] He married Katharina Krapp (Katharina article from the German Wikipedia), (1497–1557) daughter of Wittenberg's mayor, on 25 November 1520.[11] They had four children: Anna (Anna article from the German Wikipedia), Philipp, Georg, and Magdalen.[4]

Theological disputes

In the beginning of 1521 in his Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio (Wittenberg, n.d.), he defended Luther. He argued that Luther rejected only papal and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture.[12] But while Luther was absent at Wartburg Castle, during the disturbances caused by the Zwickau prophets, Melanchthon wavered.

The appearance of Melanchthon's Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theologicae (Wittenberg and Basel, 1521) was of subsequent importance for Reformation. Melanchthon presented the new doctrine of Christianity under the form of a discussion of the "leading thoughts" of the Epistle to the Romans. Loci communes began the gradual rise of the Lutheran scholastic tradition, and the later theologians Martin Chemnitz,[lower-alpha 3] Mathias Haffenreffer, and Leonhard Hutter expanded upon it.[13] Melanchthon continued to lecture on the classics.

On a journey in 1524 to his native town, he encountered the papal legate, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, who tried to draw him from Luther's cause. In his Unterricht der Visitatorn an die Pfarherrn im Kurfürstentum zu Sachssen (1528) Melanchthon presented the evangelical doctrine of salvation as well as regulations for churches and schools.

In 1529 he accompanied the elector to the Diet of Speyer. His hopes of inducing the Holy Roman Empire party to a recognition of the Reformation were not fulfilled. A friendly attitude towards the Swiss at the Diet was something he later changed, calling Huldrych Zwingli's doctrine of the Lord's Supper "an impious dogma".

Augsburg Confession

.JPG.webp)

The composition now known as the Augsburg Confession was laid before the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, and would come to be considered perhaps the most significant document of the Protestant Reformation. While the confession was based on Luther's Marburg and Schwabach articles, it was mainly the work of Melanchthon; although it was commonly thought of as a unified statement of doctrine by the two reformers, Luther did not conceal his dissatisfaction with its irenic tone. Indeed, some would criticize Melanchthon's conduct at the Diet as unbecoming of the principle he promoted, implying that faith in the truth of his cause should logically have inspired Melanchthon to a firmer and more dignified posture. Others point out that he had not sought the part of a political leader, suggesting that he seemed to lack the requisite energy and decision for such a role and may simply have been a lackluster judge of human nature.

Melanchthon then settled into the comparative quiet of his academic and literary labours. His most important theological work of this period was the Commentarii in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos (Wittenberg, 1532), noteworthy for introducing the idea that "to be justified" means "to be accounted just", whereas the Apology had placed side by side the meanings of "to be made just" and "to be accounted just". Melanchthon's increasing fame gave occasion for prestigious invitations to Tübingen (September 1534), France, and England but consideration of the elector caused him to refuse them.

Discussions on Lord's Supper and justification

Melanchthon played an important role in discussions concerning the Lord's Supper which began in 1531. He approved fully of the Wittenberg Concord sent by Bucer to Wittenberg, and at the instigation of the Landgrave of Hesse discussed the question with Bucer in Kassel, at the end of 1534. He eagerly laboured for an agreement on this question, for his patristic studies and the Dialogue (1530) of Johannes Oecolampadius had made him doubt the correctness of Luther's doctrine. Moreover, after the death of Zwingli and the change of the political situation his earlier scruples in regard to a union lost their weight. Bucer did not go so far as to believe with Luther that the true body of Christ in the Lord's Supper is bitten by the teeth, but admitted the offering of the body and blood in the symbols of bread and wine. Melanchthon discussed Bucer's views with the most prominent adherents of Luther; but Luther himself would not agree to a mere veiling of the dispute. Melanchthon's relation to Luther was not disturbed by his work as a mediator, although Luther for a time suspected that Melanchthon was "almost of the opinion of Zwingli" nevertheless he desired to "share his heart with him".[14]

During his sojourn in Tübingen in 1536 Melanchthon was heavily criticised by Cordatus, preacher in Niemeck, because he had taught that works are necessary for salvation. In the second edition of his Loci (1535), he abandoned his earlier strict doctrine of determinism which went even beyond that of Augustine of Hippo and in its place taught more clearly his so-called Synergism. He repudiated the criticism of Cordatus in a letter to Luther and his other colleagues stating that he had never departed from their common teachings on this subject and in the Antinomian Controversy of 1537 Melanchthon was in harmony with Luther.[14]

Controversies with Flacius

_and-or_Workshop_-_Portrait_of_Philip_Melanchton.jpg.webp)

The final period of Melanchthon's life began with controversies over the Interims and the Adiaphora (1547). He rejected the Augsburg Interim, which the emperor sought to force upon the defeated Protestants. During negotiations concerning the Leipzig Interim he made controversial concessions. In agreeing to various Catholic usages, Melanchthon held the opinion that they are adiaphora, if nothing is changed in the pure doctrine and the sacraments which Jesus instituted. However he disregarded the position that concessions made under such circumstances have to be regarded as a denial of Evangelical convictions.[15]

Melanchthon himself regretted his actions.

After Luther's death he became seen by many as the "theological leader of the German Reformation"[16] although the Gnesio-Lutherans with Matthias Flacius at their head accused him and his followers of heresy and apostasy. Melanchthon bore all accusations with patience, dignity, and self-control.[15]

Disputes with Osiander and Stancaro

In his controversy on justification with Andreas Osiander Melanchthon satisfied all parties. He took part also in a controversy with Stancaro, who held that Christ was our justification only according to his human nature.[15]

He was also still a strong opponent of the Catholics, for it was by his advice that the Elector of Saxony declared himself ready to send deputies to a council to be convened at Trent, but only under the condition that the Protestants should have a share in the discussions, and that the Pope should not be considered as the presiding officer and judge. As it was agreed upon to send a confession to Trent, Melanchthon drew up the Confessio Saxonica which is a repetition of the Augsburg Confession, discussing, however, in greater detail, but with moderation, the points of controversy with Rome. He on his way to Trent at Dresden saw the military preparations of Maurice of Saxony, and after proceeding as far as Nuremberg, returned to Wittenberg in March 1552, for Maurice had turned against the emperor. Owing to his act, the condition of the Protestants became more favourable and were still more so at the Peace of Augsburg (1555), but Melanchthon's labours and sufferings increased from that time.[15]

The last years of his life were embittered by the disputes over the Interim and the freshly started controversy on the Lord's Supper. As the statement "good works are necessary for salvation" appeared in the Leipzig Interim, its Lutheran opponents attacked in 1551 Georg Major, the friend and disciple of Melanchthon, so Melanchthon dropped the formula altogether, seeing how easily it could be misunderstood.[15]

But all his caution and reservation did not hinder his opponents from continually working against him, accusing him of synergism and Zwinglianism. At the Colloquy of Worms in 1557 which he attended only reluctantly, the adherents of Flacius and the Saxon theologians tried to avenge themselves by thoroughly humiliating Melanchthon, in agreement with the malicious desire of the Catholics to condemn all heretics, especially those who had departed from the Augsburg Confession, before the beginning of the conference. As this was directed against Melanchthon himself, he protested, so that his opponents left, greatly to the satisfaction of the Catholics who now broke off the colloquy, throwing all blame upon the Protestants. The Reformation in the sixteenth century did not experience a greater insult, as Friedrich Nietzsche says. Nevertheless, Melanchthon persevered in his efforts for the peace of the church, suggesting a synod of the Evangelical party and drawing up for the same purpose the Frankfurt Recess, which he defended later against the attacks of his enemies.[15]

More than anything else the controversies on the Lord's Supper embittered the last years of his life. The renewal of this dispute was due to the victory in the Reformed Church of the Calvinistic doctrine and its influence upon Germany. To its tenets Melanchthon never gave his assent, nor did he use its characteristic formulas. The personal presence and self-impartation of Christ in the Lord's Supper were especially important for Melanchthon; but he did not definitely state how body and blood are related to this. Although rejecting the physical act of mastication, he nevertheless assumed the real presence of the body of Christ and therefore also a real self-impartation. Melanchthon differed from John Calvin also in emphasizing the relation of the Lord's Supper to justification.[17]

Marian views

Melanchthon viewed any veneration of saints rather critically but developed positive commentaries about Mary. In his Annotations in Evangelia commenting on Luke 2:52, he discusses the faith of Mary, "she kept all things in her heart" which to Melanchthon is a call to the church to follow her example.[18] During the marriage at Cana, Melanchthon points out that Mary went too far, asking for more wine, misusing her position. But she was not upset, when Jesus gently scolded her.[19] Mary was negligent, when she lost her son in the temple, but she did not sin.[19] Mary was conceived with original sin like every other human being, but she was spared the consequences of it. Consequently, Melanchthon opposed the feast of the Immaculate Conception, which in his days, although not dogma, was celebrated in several cities and had been approved at the Council of Basel in 1439.[20] He declared that the Immaculate Conception was an invention of monks.[18] Mary is a representation (Typus) of the church and in the Magnificat, Mary spoke for the whole church. Standing under the cross, Mary suffered like no other human being. Consequently, Christians have to unite with her under the cross, in order to become Christ-like.[18]

Views on natural philosophy

In lecturing on the Librorum de judiciis astrologicis of Ptolemy in 1535–1536, Melanchthon expressed to students his interest in Greek mathematics, astronomy and astrology. He considered that a purposeful God had reasons to exhibit comets and eclipses.[21] He was the first to print a paraphrased edition of Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos in Basel, 1554.[22] Natural philosophy, in his view, was directly linked to Providence, a point of view that was influential in curriculum change after the Protestant Reformation in Germany.[23] In the period 1536–1539 he was involved in three academic innovations: the refoundation of Wittenberg along Protestant lines, the reorganization at Tübingen, and the foundation of the University of Leipzig.[24]

Death

Before these theological dissensions were settled, Melanchthon died. Only a few days before his death, he had written a note which gave his reasons for not fearing death. On the left of the note were the words, "You will be delivered from sins, and be freed from the acrimony and fury of theologians"; on the right, "You will go to the light, see God, look upon his Son, learn those wonderful mysteries which you have not been able to understand in this life." The immediate cause of death was a severe cold which he had contracted on a journey to Leipzig in March 1560, followed by a fever that consumed his strength. His body had already been weakened by many sufferings.[25] He was pronounced dead on 19 April 1560.[26]

In Melanchthon's last moments, he continued to worry over the desolate condition of the church. He strengthened himself in almost uninterrupted praying and in listening to passages of Scripture. The words of John 1:11-12 were especially significant to him. "His own received him not; but as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God." When Caspar Peucer, his son-in-law, asked him if he wanted anything, he replied, "Nothing but heaven." His body was buried beside Luther's in the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg.[25]

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod on 16 February, his birthday, and in the calendar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on 25 June, the date of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession.

Estimation of his works and character

Melanchthon's importance for the Reformation lay essentially in the fact that he systematized Luther's ideas, defended them in public, and made them the basis of a religious education. These two figures, by complementing each other, could be said to have harmoniously achieved the results of the Reformation. Melanchthon was impelled by Luther to work for the Reformation; his own inclinations would have kept him a student. Without Luther's influence Melanchthon would have been "a second Erasmus", although his heart was filled with a deep religious interest in the Reformation. While Luther scattered the sparks among the people, Melanchthon by his humanistic studies won the sympathy of educated people and scholars for the Reformation. Besides Luther's strength of faith, Melanchthon's many-sidedness and calmness, as well as his temperance and love of peace, had a share in the success of the movement.[25]

Both were aware of their mutual position and they thought of it as a divine necessity of their common calling. Melanchthon wrote in 1520, "I would rather die than be separated from Luther", whom he afterward compared to Elijah, and called "the man full of the Holy Ghost". In spite of the strained relations between them in the last years of Luther's life, Melanchthon exclaimed at Luther's death, "Dead is the horseman and chariot of Israel who ruled the church in this last age of the world!"[25]

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's Kolosserkommentar (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised Loci above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.[25]

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." It cannot be denied, however, that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; however Melanchthon sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther.[25] In a letter to Carlowitz, before the Diet of Augsburg, he protested that Luther on account of his hot-headed nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

His work as reformer

As a reformer, Melanchthon was characterized by moderation, conscientiousness, caution, and love of peace; but these qualities were sometimes said to only be lack of decision, consistence, and courage. Often, however, his actions are shown stemming not from anxiety for his own safety, but from regard for the welfare of the community and for the quiet development of the church. Melanchthon was not said to lack personal courage, but rather he was said to be less of an aggressive than of a passive nature. When he was reminded how much power and strength Luther drew from his trust in God, he answered, "If I myself do not do my part, I can not expect anything from God in prayer." His nature was seen to be inclined to suffer with faith in God that he would be released from every evil rather than to act valiantly with his aid. The distinction between Luther and Melanchthon is well brought out in Luther's letters to the latter (June 1530):[25]

To your great anxiety by which you are made weak, I am a cordial foe; for the cause is not ours. It is your philosophy, and not your theology, which tortures you so, – as though you could accomplish anything by your useless anxieties. So far as the public cause is concerned, I am well content and satisfied; for I know that it is right and true, and, what is more, it is the cause of Christ and God himself. For that reason, I am merely a spectator. If we fall, Christ will likewise fall; and if he fall, I would rather fall with Christ than stand with the emperor.[27]

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the church." He stood toward the history of the church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of Augustine, but also of the Greek Fathers.[28]

His attitude in matters of worship was conservative, and in the Leipsic Interim he was said by Cordatus and Schenk even to be Crypto-Catholic. He never strove for a reconciliation with Catholicism at the price of pure doctrine. He attributed more value to the external appearance and organization of the Church than Luther did, as can be seen from his whole treatment of the "doctrine of the church". The ideal conception of the church, which the reformers opposed to the organization of the Roman Church, which was expressed in his Loci of 1535, lost for him after 1537 its former prominence, when he began to emphasize the conception of the true visible church as it may be found among the Protestants.

He believed that the relation of the church to God was that the church held the divine office of the ministry of the Gospel. The universal priesthood was for Melanchthon as for Luther no principle of an ecclesiastical constitution, but a purely religious principle. In accordance with this idea Melanchthon tried to keep the traditional church constitution and government, including the bishops. He did not want, however, a church altogether independent of the state, but rather, in agreement with Luther, he believed it the duty of the secular authorities to protect religion and the church. He looked upon the consistories as ecclesiastical courts which therefore should be composed of spiritual and secular judges, for to him the official authority of the church did not lie in a special class of priests, but rather in the whole congregation, to be represented therefore not only by ecclesiastics, but also by laymen. Melanchthon in advocating church union did not overlook differences in doctrine for the sake of common practical tasks.[28]

The older he grew, the less he distinguished between the Gospel as the announcement of the will of God, and right doctrine as the human knowledge of it. Therefore, he took pains to safeguard unity in doctrine by theological formulas of union, but these were made as broad as possible and were restricted to the needs of practical religion.[28]

As scholar

As a scholar Melanchthon embodied the entire spiritual culture of his age. At the same time he found the simplest, clearest, and most suitable form for his knowledge; therefore his manuals, even if they were not always original, were quickly introduced into schools and kept their place for more than a century. Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He was, alongside other luminaries such as Erasmus, an important figure in the movement sometimes called Christian humanism, which has exerted a lasting influence upon scientific life in Germany.[28] His works were not always new and original, but they were clear, intelligible, and answered their purpose. His style is natural and plain, better, however, in Latin and Greek than in German. He was not without natural eloquence, although his voice was weak.[28]

Melanchthon wrote numerous treatises dealing with education and learning that present some of his key thoughts on learning, including his views on the basis, method, and goal of reformed education. In his "Book of Visitation", Melanchthon outlines a school plan that recommends schools to teach Latin only. Here he suggests children should be broken up into three distinct groups: children who are learning to read, children who know how to read and are ready to learn grammar, and children who are well-trained in grammar and syntax.[29] Melanchthon also believed that the disciplinary system of the classical "seven liberal arts", and the sciences studied in the higher faculties could not encompass the new revolutionary discoveries of the age in terms of either content or method. He expanded the traditional categorization of science in several directions, incorporating not only history, geography and poetry but also the new natural sciences in his system of scholarly disciplines.

As theologian

As a theologian, Melanchthon did not show so much creative ability, but rather a genius for collecting and systematizing the ideas of others, especially of Luther, for the purpose of instruction. He kept to the practical, and cared little for connection of the parts, so his Loci were in the form of isolated paragraphs. The fundamental difference between Luther and Melanchthon lies not so much in the latter's ethical conception, as in his humanistic mode of thought which formed the basis of his theology and made him ready not only to acknowledge moral and religious truths outside of Christianity, but also to bring Christian truth into closer contact with them, and thus to mediate between Christian revelation and ancient philosophy.[28]

Melanchthon's views differed from Luther's only in some modifications of ideas. Melanchthon looked upon the law as not only the correlate of the Gospel, by which its effect of salvation is prepared, but as the unchangeable order of the spiritual world which has its basis in God himself. He furthermore reduced Luther's much richer view of redemption to that of legal satisfaction. He did not draw from the vein of mysticism running through Luther's theology, but emphasized the ethical and intellectual elements.[28]

After giving up determinism and absolute predestination and ascribing to man a certain moral freedom, he tried to ascertain the share of free will in conversion, naming three causes as concurring in the work of conversion, the Word, the Spirit, and the human will, not passive, but resisting its own weakness. Since 1548 he used the definition of freedom formulated by Erasmus, "the capability of applying oneself to grace."[28]

His definition of faith lacks the mystical depth of Luther. In dividing faith into knowledge, assent, and trust, he made the participation of the heart subsequent to that of the intellect, and so gave rise to the view of the later orthodoxy that the establishment and acceptation of pure doctrine should precede the personal attitude of faith. To his intellectual conception of faith corresponded also his view that the Church also is only the communion of those who adhere to the true belief and that her visible existence depends upon the consent of her unregenerated members to her teachings.[30]

Finally, Melanchthon's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, lacking the profound mysticism of faith by which Luther united the sensual elements and supersensual realities, demanded at least their formal distinction.[31]

The development of Melanchthon's beliefs may be seen from the history of the Loci. In the beginning Melanchthon intended only a development of the leading ideas representing the Evangelical conception of salvation, while the later editions approach more and more the plan of a text-book of dogma. At first he uncompromisingly insisted on the necessity of every event, energetically rejected the philosophy of Aristotle, and had not fully developed his doctrine of the sacraments. In 1535 he treated for the first time the doctrine of God and that of the Trinity; rejected the doctrine of the necessity of every event and named free will as a concurring cause in conversion. The doctrine of justification received its forensic form and the necessity of good works was emphasized in the interest of moral discipline. The last editions are distinguished from the earlier ones by the prominence given to the theoretical and rational element.[31]

As moralist

In ethics Melanchthon preserved and renewed the tradition of ancient morality and represented the Protestant conception of life. His books bearing directly on morals were chiefly drawn from the classics, and were influenced not so much by Aristotle as by Cicero. His principal works in this line were Prolegomena to Cicero's De officiis (1525); Enarrationes librorum Ethicorum Aristotelis (1529); Epitome philosophiae moralis (1538); and Ethicae doctrinae elementa (1550).[31]

In his Epitome philosophiae moralis Melanchthon treats first the relation of philosophy to the law of God and the Gospel. Moral philosophy, it is true, does not know anything of the promise of grace as revealed in the Gospel, but it is the development of the natural law implanted by God in the heart of man, and therefore representing a part of the divine law. The revealed law, necessitated because of sin, is distinguished from natural law only by its greater completeness and clearness. The fundamental order of moral life can be grasped also by reason; therefore the development of moral philosophy from natural principles must not be neglected. Melanchthon therefore made no sharp distinction between natural and revealed morals.[31]

His contribution to Christian ethics in the proper sense must be sought in the Augsburg Confession and its Apology as well as in his Loci, where he followed Luther in depicting the Protestant ideal of life, the free realization of the divine law by a personality blessed in faith and filled with the spirit of God.[31]

As exegete

Melanchthon's formulation of the authority of Scripture became the norm for the following time. The principle of his hermeneutics is expressed in his words: "Every theologian and faithful interpreter of the heavenly doctrine must necessarily be first a grammarian, then a dialectician, and finally a witness." By "grammarian" he meant the philologist in the modern sense who is master of history, archaeology, and ancient geography. As to the method of interpretation, he insisted with great emphasis upon the unity of the sense, upon the literal sense in contrast to the four senses of the scholastics. He further stated that whatever is looked for in the words of Scripture, outside of the literal sense, is only dogmatic or practical application.[31]

His commentaries, however, are not grammatical, but are full of theological and practical matter, confirming the doctrines of the Reformation, and edifying believers. The most important of them are those on Genesis, Proverbs, Daniel, the Psalms, and especially those on the New Testament, on Romans (edited in 1522 against his will by Luther), Colossians (1527), and John (1523). Melanchthon was the constant assistant of Luther in his translation of the Bible, and both the books of the Maccabees in Luther's Bible are ascribed to him. A Latin Bible published in 1529 at Wittenberg is designated as a common work of Melanchthon and Luther.[31]

As historian and preacher

In the sphere of historical theology the influence of Melanchthon may be traced until the seventeenth century, especially in the method of treating church history in connection with political history. His was the first Protestant attempt at a history of dogma, Sententiae veterum aliquot patrum de caena domini (1530) and especially De ecclesia et auctoritate verbi Dei (1539).[31]

Melanchthon exerted a wide influence in the department of homiletics, and has been regarded as the author, in the Protestant church, of the methodical style of preaching. He himself keeps entirely aloof from all mere dogmatizing or rhetoric in the Annotationes in Evangelia (1544), the Conciones in Evangelium Matthaei (1558), and in his German sermons prepared for George of Anhalt. He never preached from the pulpit; and his Latin sermons (Postilla) were prepared for the Hungarian students at Wittenberg who did not understand German. In this connection may be mentioned also his Catechesis puerilis (1532), a religious manual for younger students, and a German catechism (1549), following closely Luther's arrangement.[31]

From Melanchthon came also the first Protestant work on the method of theological study, so that it may safely be said that by his influence every department of theology was advanced even if he was not always a pioneer.[31]

As professor and philosopher

As a philologist and pedagogue Melanchthon was the spiritual heir of the South German Humanists, of men like Reuchlin, Jakob Wimpfeling, and Rodolphus Agricola, who represented an ethical conception of the humanities. The liberal arts and a classical education were for him paths, not only towards natural and ethical philosophy, but also towards divine philosophy. The ancient classics were for him in the first place the sources of a purer knowledge, but they were also the best means of educating the youth both by their beauty of form and by their ethical content. By his organizing activity in the sphere of educational institutions and by his compilations of Latin and Greek grammars and commentaries, Melanchthon became the founder of the learned schools of Evangelical Germany, a combination of humanistic and Christian ideals. In philosophy also Melanchthon was the teacher of the whole German Protestant world. The influence of his philosophical compendia ended only with the rule of the Leibniz-Wolff school.[32]

He started from scholasticism; but with the contempt of an enthusiastic Humanist he turned away from it and came to Wittenberg with the plan of editing the complete works of Aristotle. Under the dominating religious influence of Luther his interest abated for a time, but in 1519 he edited the Rhetoric and in 1520 the Dialectic.[33]

The relation of philosophy to theology is characterized, according to him, by the distinction between Law and Gospel. The former, as a light of nature, is innate; it also contains the elements of the natural knowledge of God which, however, have been obscured and weakened by sin. Therefore, renewed promulgation of the Law by revelation became necessary and was furnished in the Decalogue; and all law, including that in the form of natural philosophy, contains only demands, shadowings; its fulfillment is given only in the Gospel, the object of certainty in theology, by which also the philosophical elements of knowledge – experience, principles of reason, and syllogism – receive only their final confirmation. As the law is a divinely ordered pedagogue that leads to Christ, philosophy, its interpreter, is subject to revealed truth as the principal standard of opinions and life.[33]

Besides Aristotle's Rhetoric and Dialectic he published De dialecta libri iv (1528), Erotemata dialectices (1547), Liber de anima (1540), Initia doctrinae physicae (1549), and Ethicae doctrinae elementa (1550).[33]

Personal appearance and character

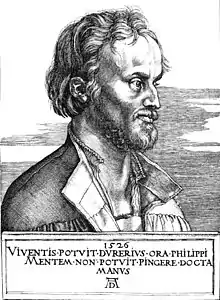

There have been preserved original portraits of Melanchthon by three famous painters of his time – by Hans Holbein the Younger in various versions, one of them in the Royal Gallery of Hanover, by Albrecht Dürer (made in 1526, meant to convey a spiritual rather than physical likeness and said to be eminently successful in doing so), and by Lucas Cranach the Elder.[33] Melanchthon was dwarfish, misshapen, and physically weak,[34] although he is said to have had a bright and sparkling eye, which kept its colour till the day of his death.[33]

He was never in perfectly sound health, and managed to perform as much work as he did only by reason of the extraordinary regularity of his habits and his great temperance. He set no great value on money and possessions; his liberality and hospitality were often misused in such a way that his old faithful Swabian servant had sometimes difficulty in managing the household. His domestic life was happy. He called his home "a little church of God", always found peace there, and showed a tender solicitude for his wife and children. To his great astonishment a French scholar found him rocking the cradle with one hand, and holding a book in the other.[33]

His noble soul showed itself also in his friendship for many of his contemporaries; "there is nothing sweeter nor lovelier than mutual intercourse with friends", he used to say. His most intimate friend was Joachim Camerarius, whom he called the half of his soul. His extensive correspondence was for him not only a duty, but a need and an enjoyment. His letters form a valuable commentary on his whole life, as he spoke out his mind in them more unreservedly than he was wont to do in public life. A peculiar example of his sacrificing friendship is furnished by the fact that he wrote speeches and scientific treatises for others, permitting them to use their own signature. But in the kindness of his heart he was said to be ready to serve and assist not only his friends, but everybody. His whole nature adapted him especially to the intercourse with scholars and men of higher rank, while it was more difficult for him to deal with the people of lower station. He never allowed himself or others to exceed the bounds of nobility, honesty, and decency. He was very sincere in the judgment of his own person, acknowledging his faults even to opponents like Flacius, and was open to the criticism even of such as stood far below him. In his public career he sought not honour or fame, but earnestly endeavoured to serve the church and the cause of truth. His humility and modesty had their root in his personal piety. He laid great stress upon prayer, daily meditation on the Bible, and attendance of public service.[33]

See also

- Gottlob Frege, notable descendant of Melanchthon

- List of Erasmus's correspondents

- Dimitrije Ljubavić

- Philippists

- Ubiquitarians

Notes

- /məˈlæŋkθən/ mə-LANK-thən, German pronunciation: [meˈlançtɔn] (

listen); Latin: Philippus Melanchthon.

listen); Latin: Philippus Melanchthon. - German pronunciation: [ˈʃvaʁtsʔeːɐ̯t] (

listen).

listen). - For an example of this from Chemnitz, see Chemnitz 2004, which is excerpted from his Loci Theologici.

References

- Richard 1898, p. 379.

- Richard 1898, p. 3.

- Richard 1898, p. 11.

- Manschreck 2011.

- Löffler 1911, p. 151; Pauck 1969, p. 4.

- Wyk, Van; (Natie), Ignatius W. C. (2017). "Philipp Melanchthon: A short introduction". HTS Theological Studies. 73 (1): 1–8. doi:10.4102/hts.v73i1.4672. ISSN 0259-9422.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2005). Encyclopedia of Protestantism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-6983-5.

- Brosseder 2005.

- Rupp 1996.

- Richard 1898, pp. 57–58.

- Lohrmann 2012, p. 432; Manschreck 2011; Schofield 2006, p. 20.

- Richard 1898, p. 71.

- Jacobs 1899.

- Kirn 1910, p. 280.

- Kirn 1910, p. 281.

- Tondo, Douglas J. Del (February 2008). Jesus' Words on Salvation. Infinity. ISBN 978-0-7414-4357-1.

- Kirn 1910, pp. 281–282.

- Bäumer 1992, p. 424.

- Bäumer 1992, p. 425.

- Heal 2007, p. 25.

- Billeskov Jansen 1991, pp. 107–108.

- Heilen 2010, p. 70.

- Kusukawa 1995, pp. 185–186.

- Kusukawa 1999, p. xxxiii.

- Kirn 1910, p. 282.

- Kolb 2012, p. 142.

- Kirn 1910, pp. 282–83.

- Kirn 1910, p. 283.

- Eby 1931.

- Kirn 1910, pp. 283–284.

- Kirn 1910, p. 284.

- Kirn 1910, pp. 284–85.

- Kirn 1910, p. 285.

- Huberman, Jack (3 March 2008). The Quotable Atheist: Ammunition for Nonbelievers, Political Junkies, Gadflies, and Those Generally Hell-Bound. ISBN 978-1-56858419-5. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

Works cited

- Bäumer, Remigius (1992). "Reformation". Marienlexikon (in German). St. Ottilien: EOS.

- Billeskov Jansen, F. J. (1991). "Postscript". Oration on the Philosophical Studies Necessary for the Student of Theology. By Sinning, Jens Andersen. Jacobsen, Eric (ed.). Translated by Høgel, Christian; Fisher, Peter; Stoner, David. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-144-6.

- Brosseder, Claudia (2005). "The Writing in the Wittenberg Sky: Astrology in Sixteenth-Century Germany". Journal of the History of Ideas. 66 (4): 557–576. doi:10.1353/jhi.2005.0049. ISSN 0022-5037. S2CID 170230348.

- Chemnitz, Martin (2004). On Almsgiving (PDF). Translated by Kellerman, James A. St. Louis, Missouri: LCMS World Relief and Human Care. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Eby, Frederick (1931). Early Protestant Educators: The Educational Writings of Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Other Leaders of Protestant Thought. New York.

- Heal, Bridget (2007). The Cult of the Virgin Mary in Early Modern Germany. Cambridge University Press.

- Heilen, Stephan (2010). "Ptolemy's Doctrine of the Terms and Its Reception". In Jones, Alexander (ed.). Ptolemy in Perspective: Use and Criticism of his Work from Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Archimedes: New Studies in the History of Science and Technology. Vol. 23. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp. 45–93. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2788-7_3. ISBN 978-90-481-2787-0. ISSN 1385-0180.

- Jacobs, Henry Eyster (1899). "Scholasticism in the Luth. Church". In Jacobs, Henry Eyster; Haas, John A. W. (eds.). The Lutheran Cyclopedia. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 434–435. Retrieved 4 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Kirn, Otto (1910). "Melanchthon, Philipp". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 7 (3rd ed.). New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 279–86. Retrieved 18 February 2021 – via Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

This article incorporates material from this public-domain publication. - Kolb, Robert (2012). "Melanchthon's Doctrinal Last Will and Testament: The Responsiones ad articulos Bavaricae inquisitionis as His Final Confession of Faith". In Dingel, Irene; Kolb, Robert; Kuropka, Nicole; Wengert, Timothy J. (eds.). Philip Melanchthon: Theologian in Classroom, Confession, and Controversy. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 141–160. ISBN 978-3-525-55047-2.

- Kusukawa, Sachiko (1995). The Transformation of Natural Philosophy: The Case of Philip Melanchthon. Ideas in Context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47347-7. ISSN 0962-4945.

- ——— (1999). "Chronology". Orations on Philosophy and Education. By Melanchthon, Philip. Kusukawa, Sachiko (ed.). Translated by Salazar, Christine F. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58677-1.

- Löffler, Klemens (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 151–154 – via Wikisource.

- Lohrmann, Martin (2012). "Melanchthon, Philip, 1497–1560". In Whitford, David M. (ed.). T&T Clark Companion to Reformation Theology. London: T&T Clark (published 2014). pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-567-15366-1.

- Manschreck, Clyde L. (2011). "Philipp Melanchthon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Pauck, Wilhelm, ed. (1969). "Loci Communes Theologici: Editor's Introduction". Melanchthon and Bucer. Library of Christian Classics. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-664-24164-3.

- Richard, James William (1898). Philip Melanchthon: The Protestant Preceptor of Germany, 1497–1560. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 4 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.(also at Forgotten Books)

- Rupp, Horst F. (1996). "Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560)". Profiles of Famous Educators. Prospects. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 26 (3): 610–21. doi:10.1007/BF02195060. ISSN 1573-9090. S2CID 189873577.

- Schofield, John (2006). Philip Melanchthon and the English Reformation. St Andrews Studies in Reformation History. Aldershot, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5567-1.

- Whiton, James Maurice (1905). . In Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore (eds.). New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 13 (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. pp. 285–86 – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates material from this public-domain publication.

Further reading

- Andreatta, Eugenio (1996). Lutero e Aristotele (in Italian). Padova, Italy: Cusl Nuova Vita. ISBN 978-88-8260-010-5.

- Birnstein, Uwe (2010). Der Humanist: Was Philipp Melanchthon Europa lehrte (in German). Berlin: Wichern-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-88981-282-7.

- Caemmerer, Richard R. (2000). "Melanchthon, Philipp". In Lueker, Erwin L.; Poellot, Luther; Jackson, Paul (eds.). Christian Cyclopedia. St. Louis, Missouri: Concordia Publishing House. Retrieved 5 November 2017 – via Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod.

- Cuttini, Elisa (2005). Unità e pluralità nella tradizione europea della filosofia pratica di Aristotele: Girolamo Savonarola, Pietro Pomponazzi e Filippo Melantone (in Italian). Soveria Mannelli, Italy: Rubbettino. ISBN 978-88-498-1575-7.

- DeCoursey, Matthew (2001). "Continental European Rhetoricians, 1400–1600, and Their Influence in Renaissance England". In Malone, Edward A. (ed.). Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 236: British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500–1660, First Series. Detroit, Michigan: Gale. pp. 309–343. ISBN 978-0-7876-4653-0.

- Estes, James M. (1998). "The Role of Godly Magistrates in the Church: Melanchthon as Luther's Interpreter and Collaborator". Church History. Cambridge University Press. 67 (3): 463–483. doi:10.2307/3170941. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3170941. S2CID 162335827.

- Fuchs, Thorsten (2008). Philipp Melanchthon als neulateinischer Dichter in der Zeit der Reformation (in German). Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr. ISBN 978-3-8233-6340-8.

- Graybill, Gregory B. (2010). Evangelical Free Will: Philipp Melanchthon's Doctrinal Journey on the Origins of Faith. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958948-7.

- Jung, Martin H. (2010). Philipp Melanchthon und seine Zeit (in German). Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-55006-9.

- Kusukawa, Sachiko (2004). "Melanchthon". In Bagchi, David; Steinmetz, David C. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Reformation Theology. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–67. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521772249.007. ISBN 978-0-521-77662-2.

- Laitakari-Pyykkö, Anja-Leena (2013). Philip Melanchthon's Influence on English Theological Thought During the Early English Reformation (PhD dissertation). Helsinki: University of Helsinki. hdl:10138/41764. ISBN 978-952-10-9447-7.

- Ledderhose, Karl Friedrich (1855). The Life of Philip Melanchthon. Translated by Krotel, G. F. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston (published 2012). LCCN 22011423. Retrieved 5 November 2017 – via Project Gutenburg.

- Maag, Karin, ed. (1999). Melanchthon in Europe: His Work and Influence beyond Wittenberg. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. ISBN 978-0-8010-2223-4.

- Mack, Peter (2011). "Northern Europe, 1519–1545: The Age of Melanchthon". A History of Renaissance Rhetoric, 1380–1620. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 104–135. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199597284.003.0006. ISBN 978-0-19-959728-4.

- Manschreck, Clyde L. (1958). Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer. New York: Abingdon Press.

- Meerhoff, Kees (1994). "The Significance of Philip Melanchthon's Rhetoric in the Renaissance". In Mack, Peter (ed.). Renaissance Rhetoric. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 46–62. ISBN 978-0-312-10184-8.

- Melanchthon, Philip (1969). "Loci Communes Theologici". In Pauck, Wilhelm (ed.). Melanchthon and Bucer. Library of Christian Classics. Translated by Satre, Lowell J.; Pauck, Wilhelm. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. pp. 18–152. ISBN 978-0-664-24164-3.

- ——— (2002). "History of the Life and Acts of Dr Martin Luther". In Vandiver, Elizabeth; Keen, Ralph; Frazel, Thomas D. (eds.). Luther's Lives: Two Contemporary Accounts of Martin Luther. Translated by Frazel, Thomas D. Manchester: Manchester University Press (published 2003). pp. 14–39. ISBN 978-0-7190-6802-7.

- Rogness, Michael (1969). Philip Melanchthon: Reformer without Honor. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Augsburg Publishing House. OCLC 905626473.

- Scheible, Heinz (1990). "Luther and Melanchthon". Lutheran Quarterly. 4 (3): 317–339. ISSN 0024-7499.

- ——— (1996). "Melanchthon, Philipp". In Hillerbrand, Hans J. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195064933.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-506493-3.

- Smith, Preserved (1911). The Life and Letters of Martin Luther. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. LCCN 11015608. Retrieved 5 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Sotheby, Samuel Leigh (1839). Observations upon the Handwriting of Philip Melanchthon. London. OCLC 13625108. Retrieved 5 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Servetus, Michael (2015) [1553]. Regarding the Mystery of the Trinity and the Teaching of the Ancients to Philip Melanchthon and his Colleagues. Translated by Hillar, Marian; Hoffman, Christopher A. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-1-4955-0336-8.

- Stupperich, Robert (2006) [1965]. Melanchthon: The Enigma of the Reformation. Translated by Fischer, Robert H. Cambridge, England: James Clarke & Co. ISBN 978-0-227-17244-5.

- Wengert, Timothy J. (1998). Human Freedom, Christian Righteousness: Philip Melanchthon's Exegetical Dispute with Erasmus of Rotterdam. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511529-1.

- Wengert, Timothy J.; Graham, M. Patrick, eds. (1997). Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560) and the Commentary. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-684-2.

External links

- Works by or about Philip Melanchthon at Internet Archive

- Works by Philip Melanchthon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Philip Melanchthon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works at Open Library

- Works by Philip Melanchthon at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Philip Melanchthon at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Examen eorum, qui oudiuntur ante ritum publicae ordinotionis, qua commendatur eis ministerium Evangelli: Traditum Vuitebergae, Anno 1554, at Opolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa