Pashtuns

Pashtuns (/ˈpʌʃˌtʊn/, /ˈpɑːʃˌtʊn/, /ˈpæʃˌtuːn/; Pashto: پښتانه, Pəx̌tānə́),[27] also known as Pakhtuns[28] or Pathans,[lower-alpha 1] are an Iranian ethnic group[32] who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan.[33][34] They were historically referred to as Afghans[lower-alpha 2] until the 1970s,[40] when the term's meaning evolved into that of a demonym for all residents of Afghanistan, including those outside of the Pashtun ethnicity.[40][41]

پښتانه | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 49+ million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 36,679,879 (2021)[2] | |

| 15,735,893 (2021)[3] | |

| 21,677 (Pashto-speakers; 2011) – 3,200,000 (non-speakers; 2018)[4][5][6][7] | |

| 338,315 (2009)[8] | |

| 138,554 (2010)[9] | |

| 110,000 (1993)[10] | |

| 100,000 (2009)[11] | |

| 37,800 (2012)[12] | |

| 26,000 (2006)[13] | |

| 9,800 (2002)[14] | |

| 8,154 (2006)[15] | |

| 6,000 (2008)[16] | |

| 4,000 (1970)[10] | |

| 1,181[17] | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto Additional: Dari Persian (in Afghanistan) and Hindi–Urdu (in Pakistan and India)[18][19][20] | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Islam (Sunni majority, Shia minority)[21][22] Minority: Hinduism,[23][24][25] Sikhism[26] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples | |

The group's native language is Pashto, an Iranian language in the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Additionally, Dari Persian[42] serves as the second language of Pashtuns in Afghanistan[43][44] while those in the Indian subcontinent speak Urdu and Hindi (see Hindustani language) as their second language.[19][20][18][45]

Pashtuns are the 26th-largest ethnic group in the world, and the largest segmentary lineage society; there are an estimated 350–400 Pashtun tribes and clans with a variety of origin theories.[46][47][48] The total population of the Pashtun people worldwide is estimated to be around 49 million,[1] although this figure is disputed due to the lack of an official census in Afghanistan since 1979.[49] They are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and the second-largest ethnic group in Pakistan,[50] constituting around 48 percent of the total Afghan population and around 15.4 percent of the total Pakistani population.[51][52][53] In India, significant and historical communities of the Pashtun diaspora exist in the northern region of Rohilkhand as well as in major Indian cities such as Delhi and Mumbai.[54][55][7] A more recent Pashtun diaspora has formed in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf (primarily in the United Arab Emirates) as part of the larger Afghan and Pakistani diaspora in that region.[56]

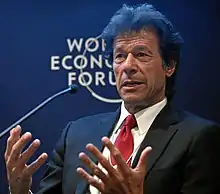

Prominent Pashtun figures include Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Abdul Ghani Khan, Ahmad Shah Durrani, Alauddin Khalji, Ayub Khan, Bahlul Lodi, Dilip Kumar, Imran Khan, Irrfan Khan, Khushal Khan, Madhubala, Malala Yousafzai, Malalai of Maiwand, Mirwais Hotak, Mohammed Daoud Khan, Pir Roshan, Rahman Baba, Salman Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, Shahid Afridi, Sher Shah Suri, and Zakir Hussain, among others.[57]

Geographic distribution

| Part of a series on |

| Pashtuns |

|---|

|

| Empires and dynasties |

|

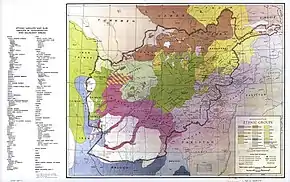

Traditional homeland

The majority of Pashtuns are found in the native Pashtun homeland, located south of the Hindu Kush which is in Afghanistan and west of the Indus River in Pakistan, principally around the Sulaiman Mountains.[58][59][60][61][33] It is believed that the Pashtuns emerged from the region around Kandahar and the Sulaiman Mountains,[60] roughly around the ancient region of Arachosia,[62] and expanded from there between the 13th and 16th centuries to the adjoining areas of modern day Afghanistan and Pakistan.[63][64][65] Starting in the 1880s, various Pashtun-dominated governments of Afghanistan have pursued policies, called Pashtunization, aimed towards settling more ethnic Pashtuns in non-Pashtun regions, particularly the northern region of Afghanistan.[66][67][68][69][70] Metropolitan centres within Pashtun dominated areas include Kandahar, Quetta, Jalalabad, Mardan, Mingora and Peshawar.[71]

Karachi is home to the largest community of Pashtuns outside of the native homeland (with estimates of around 7 million).[72][73]

India

Pashtuns in India are often commonly referred to as Pathans (the Hindustani word for Pashtun) both by themselves and other ethnic groups of the subcontinent.[74][75]

Historically, Pashtuns have settled in various cities of India before and during the British Raj in colonial India. These include Bombay (now called Mumbai), Delhi, Calcutta, Rohilkhand, Jaipur and Bangalore.[54][55][7] The settlers are descended from both Pashtuns of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan (British India before 1947). In some regions in India, they are sometimes referred to as Kabuliwala.[76]

In India significant Pashtun diaspora communities exist.[77][78] While speakers of Pashto in the country only number 21,677 as of 2011, estimates of the ethnic or ancestral Pashtun population in India range from 3,200,000[4][79][80] to 11,482,000[81] to as high as double their population in Afghanistan (approximately 30 million).[82]

The Rohilkhand region of Uttar Pradesh is named after the Rohilla community of Pashtun ancestry. They also live in the states of Maharashtra in central India and West Bengal in eastern India that each have a population of over a million with Pashtun ancestry;[83] both Bombay and Calcutta were primary locations of Pashtun migrants from Afghanistan during the colonial era.[84] There are also populations over 100,000 each in the cities of Jaipur in Rajasthan and Bangalore in Karnataka.[83] Bombay (now called Mumbai) and Calcutta both have a Pashtun population of over 1 million, whilst Jaipur and Bangalore have an estimate of around 100,000. The Pashtuns in Bangalore include the khan siblings Feroz, Sanjay and Akbar Khan, whose father settled in Bangalore from Ghazni.[85]

Today, the Pashtuns are a collection of diversely scattered communities present across the length and breadth of India, with the largest populations principally settled in the plains of northern and central India.[86][87][88] Following the partition of India in 1947, many of them migrated to Pakistan.[86] The majority of Indian Pashtuns are Urdu-speaking communities,[86] who have assimilated into the local society over the course of generations.[89] Pashtuns have influenced and contributed to various fields in India, particularly politics, the entertainment industry and sports.[88]

Iran

Pashtuns are also found in smaller numbers in the eastern and northern parts of Iran.[90] Records as early as the mid-1600s report Durrani Pashtuns living in the Khorasan Province of Safavid Iran.[91] After the short reign of the Ghilji Pashtuns in Iran, Nader Shah defeated the last independent Ghilji ruler of Kandahar, Hussain Hotak. In order to secure Durrani control in southern Afghanistan, Nader Shah deported Hussain Hotak and large numbers of the Ghilji Pashtuns to the Mazandaran Province in northern Iran. The remnants of this once sizable exiled community, although assimilated, continue to claim Pashtun descent.[92] During the early 18th century, in the course of a very few years, the number of Durrani Pashtuns in Iranian Khorasan, greatly increased.[93] Later the region became part of the Durrani Empire itself. The second Durrani king of Afghanistan, Timur Shah Durrani was born in Mashhad.[94] Contemporary to Durrani rule in the east, Azad Khan Afghan, an ethnic Ghilji Pashtun, formerly second in charge of Azerbaijan during Afsharid rule, gained power in the western regions of Iran and Azerbaijan for a short period.[95] According to a sample survey in 1988, 75 percent of all Afghan refugees in the southern part of the Iranian Khorasan Province were Durrani Pashtuns.[96]

In other regions

Indian and Pakistani Pashtuns have utilised the British/Commonwealth links of their respective countries, and modern communities have been established starting around the 1960s mainly in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia but also in other commonwealth countries (and the United States). Some Pashtuns have also settled in the Middle East, such as in the Arabian Peninsula. For example, about 300,000 Pashtuns migrated to the Persian Gulf countries between 1976 and 1981, representing 35% of Pakistani immigrants.[97]

Due to the multiple wars in Afghanistan since the late 1970s, various waves of refugees (Afghan Pashtuns, but also a sizeable number of Tajiks, Hazara, Uzbek, Turkmen and Afghan Sikhs) have left the country as asylum seekers.[98]

There are 1.3 million Afghan refugees in Pakistan and 1 million in Iran. Others have claimed asylum in the United Kingdom, United States and European Union countries through Pakistan. [99]

Tribes

A prominent institution of the Pashtun people is the intricate system of tribes.[101] The Pashtuns remain a predominantly tribal people, but the trend of urbanisation has begun to alter Pashtun society as cities such as Kandahar, Peshawar, Quetta and Kabul have grown rapidly due to the influx of rural Pashtuns. Despite this, many people still identify themselves with various clans.

The tribal system has several levels of organisation: the tribe they are in is from four 'greater' tribal groups: the Sarbani, the Bettani, the Gharghashti, and the Karlani, the tabar (tribe), is then divided into kinship groups called khels, which in turn is divided into smaller groups (pllarina or plarganey), each consisting of several extended families called kahols.[102]

History and origins

Excavations of prehistoric sites suggest that early humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago.[104] Since the 2nd millennium BC, cities in the region now inhabited by Pashtuns have seen invasions and migrations, including by Ancient Indian peoples, Ancient Iranian peoples, the Medes, Persians, and Ancient Macedonians in antiquity, Kushans, Hephthalites, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and others. In recent times, people of the Western world have explored the area as well.[104][105][106]

The early precursors to modern-day Pashtuns may have been old Iranian tribes that spread throughout the eastern Iranian plateau.[107][108]

According to Yu. V. Gankovsky:[109]

"The Pashtuns began as a union of largely East-Iranian tribes which became the initial ethnic stratum of the Pashtun ethnogenesis, dates from the middle of the first millennium CE and is connected with the dissolution of the Epthalite (White Huns) confederacy. ... Of the contribution of the Epthalites (White Huns) to the ethnogenesis of the Pashtuns we find evidence in the ethnonym of the largest of the Pashtun tribe unions, the Abdali (Durrani after 1747) associated with the ethnic name of the Epthalites — Abdal. The Siah-posh, the Kafirs (Nuristanis) of the Hindu Kush, called all Pashtuns by a general name of Abdal still at the beginning of the 19th century."

— Gankovsky, History of Afganistan

Gankovsky proposes Ephthalite origin for Pashtuns[109][110] but others draw a different conclusion. Ghilji tribe has been connected to the Khalaj people.[111] According to Abdul Hai Habibi, some oriental scholars hold that the second largest Pasthun tribe, the Ghiljis, are the descendants of a mixed race of Hephthalite and Pakhtas who have been living in Afghanistan since the Vedic Aryan period.[103] But according to Sims-Williams, archaeological documents do not support the suggestion that the Khalaj were the Hephthalites' successors.[112] According to Georg Morgenstierne, the Durrani tribe who were known as the "Abdali" before the formation of the Durrani Empire 1747,[113] might be connected to with the Hephthalites;[114] Aydogdy Kurbanov endorses this view who proposes that after the collapse of the Hephthalite confederacy, Hephthalite likely assimilated into different local populations.[115]

The ethnogenesis of the Pashtun ethnic group is unclear but historians have come across references to various ancient peoples called Pakthas (Pactyans) between the 2nd and the 1st millennium BC,[116][117] who may be their early ancestors. However, there are many conflicting theories amongst historians and the Pashtuns themselves.[34]

Mohan Lal states:

"... the origin of the Afghans is so obscure, that no one, even among the oldest and most clever of the tribe, can give satisfactory information on this point."[118]

Willem Vogelsang states:

"Looking for the origin of Pashtuns and the Afghans is something like exploring the source of the Amazon. Is there one specific beginning? And are the Pashtuns originally identical with the Afghans? Although the Pashtuns nowadays constitute a clear ethnic group with their own language and culture, there is no evidence whatsoever that all modern Pashtuns share the same ethnic origin. In fact it is highly unlikely."[119]

Pashtuns are tied to the history of modern Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India: following Muslim conquests from the 7th to 11th centuries, many Pashtun warriors invaded and conquered much of the northern parts of South Asia during the periods of the Suris and Durranis.[120]

Linguistic origin

Pashto is generally classified as an Eastern Iranian language.[121][122][123] It shares features with the Munji language, which is the closest existing language to the extinct Bactrian,[124] but also shares features with the Sogdian language, as well as Khwarezmian, Shughni, Sanglechi, and Khotanese Saka.[125] It is suggested by some that Pashto may have originated in the Badakhshan region and is connected to a Saka language akin to Khotanese.[126] In fact major linguist Georg Morgenstierne has described Pashto as a Saka dialect and many others have observed the similarities between Pashto and other Saka languages as well, suggesting that the original Pashto speakers might have been a Saka group.[127][128] Furthemore Pashto and Ossetian, another Scythian-descending language, share cognates in their vocabulary which other Eastern Iranian languages lack[129] Cheung suggests a common isogloss between Pashto and Ossetian which he explains by an undocumented Saka dialect being spoken close to reconstructed Old Pashto which was likely spoken north of the Oxus at that time.[130] Others however have suggested a much older Iranic ancestor given the affinity to Old Avestan.[131]

Ancient historical references: Pashtun

There is mention of the tribe called Pakthās who were one of the tribes that fought against Sudas in the Dasarajna - the Battle of the Ten Kings - of the Rigveda (RV 7.18.7) dated between c. 1500 and 1200 BCE.[134] The Pakthās are mentioned:[135]

Together came the Pakthas (पक्थास), the Bhalanas, the Alinas, the Sivas, the Visanins. Yet to the Trtsus came the Ārya's Comrade, through love of spoil and heroes' war, to lead them.

— Rigveda, Book 7, Hymn 18, Verse 7

Heinrich Zimmer connects them with a tribe mentioned by Herodotus (Pactyans), and with Pashtuns in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[136][137]

Herodutus in 430 BCE mentions in the Histories:[138]

Other Indians dwell near the town of Caspatyrus[Κασπατύρῳ] and the Pactyic [Πακτυϊκῇ] country, north of the rest of India; these live like the Bactrians; they are of all Indians the most warlike, and it is they who are sent for the gold; for in these parts all is desolate because of the sand.

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 102, Section 1

These Pactyans lived on the eastern frontier of the Achaemenid Arachosia Satrapy as early as the 1st millennium BCE, present day Afghanistan.[139] Herodotus also mentions a tribe of known as Aparytai (Ἀπαρύται)[140] Thomas Holdich[141] has linked them with the Pashtun tribe: Afridis[142] as all these tribes have been placed in the Indus valley. Herodotus states:[143]

The Sattagydae, Gandarii, Dadicae, and Aparytae (Ἀπαρύται) paid together a hundred and seventy talents; this was the seventh province

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 91, Section 4

Joseph Marquart made the connection of the Pashtuns with names such as the Parsiētai (Παρσιῆται), Parsioi (Πάρσιοι) that were cited by Ptolemy 150 CE.[144] The text from Ptolemy:[145]

"The northern regions of the country are inhabited by the Bolitai, the western regions by the Aristophyloi below whom live the Parsioi (Πάρσιοι). The southern regions are inhabited by the Parsiētai (Παρσιῆται), the eastern regions by the Ambautai. The towns and villages lying in the country of the Paropanisadai are these: Parsiana Zarzaua/Barzaura Artoarta Baborana Kapisa niphanda"

— Ptolemy, 150 CE, 6.18.3-4

Strabo, the Greek geographer, in the Geographica (written between 43 BC to 23 AD) makes mention of the Pasiani (Πασιανοί), this has been identified with Pashtuns given that Pashto is an Eastern-Iranian language[146] and Pashtuns reside in the area[147] once termed Ariana.[148][149] Strabo states:[150]

"Most of the Scythians...each separate tribe has its peculiar name. All, or the greatest part of them, are nomades. The best known tribes are those who deprived the Greeks of Bactriana, the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes (Syr Darya)"

— Strabo, The Geography, Book XI, Chapter 8, Section 2

This is considered a different rendering of Ptolemy's Parsioi (Πάρσιοι).[149] Johnny Cheung,[151] reflecting on Ptolemy's Parsioi (Πάρσιοι) and Strabo's Pasiani (Πασιανοί) states: "Both forms show slight phonetic substitutions, viz. of υ for ι, and the loss of r in Pasianoi is due to perseveration from the preceding Asianoi. They are therefore the most likely candidates as the (linguistic) ancestors of modern day Pashtuns."[152]

Middle historical references: Afghan

In the Middle Ages until the advent of modern Afghanistan in the 18th century and the division of Pashtun territory by the 1893 Durand Line, Pashtuns were often referred to as ethnic "Afghans".[154]

The earliest mention of the name Afghan (Abgân - αβγανο)[35] is by Shapur I of the Sasanian Empire during the 3rd century CE.[36][37][155][156] In the 4th century the word "Afghans/Afghana" (αβγανανο) as a reference to the Pashtun people is mentioned in the Bactrian documents, they mention an Afghan chief named Bredag Watanan in connection with the Hephtalites and in the context of some stolen horses. Interestingly the documents mention the Afghans far in the north of Afghanistan around modern Kunduz, Baghlan and Samangan in historical Bactria[157][158]

"To Ormuzd Bunukan ,from Bredag Watanan ... greetings and homage from ... ) , the ( sotang ( ? ) of Parpaz ( under ) [ the glorious ) yabghu of Hephthal , the chief of the Afghans , ' the judge of Tukharistan and Gharchistan . Moreover , ' a letter [ has come hither ] from you , so I have heard how [ you have ] written ' ' to me concerning ] my health . I arrived in good health , ( and ) ( afterwards ( ? ) ' ' I heard that a message ] was sent thither to you ( saying ) thus : ... look after the farming but the order was given to you thus. You should hand over the grain and then request it from the citizens store: I will not order, so.....I Myself order And I in Respect of winter sends men thither to you then look after the farming, To Ormuzd Bunukan, Greetings"

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century

Other reference from the same documents :

"because [you] (pl.), the clan of the Afghans, said thus to me:...And you should not have denied? the men of Rob[159] [that] the Afghans took (away) the horses"

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

"[To ...]-bid the Afghan... Moreover, they are in [War]nu(?) because of the Afghans, so [you should] impose a penalty on Nat Kharagan ... ...lord of Warnu with ... ... ...the Afghan... ... "

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

The name Afghan is later recorded in the 6th century CE in the form of "Avagāṇa" [अवगाण][160] by the Indian astronomer Varāha Mihira in his Brihat-samhita.[161][162]

"It would be unfavourable to the people of Chola, the Afghans (Avagāṇa), the white Huns and the Chinese."[162]

— Varāha Mihira, 6th century CE, chapt. 11, verse 61

Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, visiting the Afghanistan region several times between 630 and 644 CE also speaks about them.[36][163] In Shahnameh 1–110 and 1–116, it is written as Awgaan.[36] According to several scholars such as V. Minorsky, the name "Afghan" is documented several times in the 982 CE Hudud-al-Alam.[155]

"Saul, a pleasant village on a mountain. In it live Afghans".[119]

— Hudud ul-'alam, 982 CE

Hudud ul-'alam also speaks of a king in Ninhar (Nangarhar), who had Muslim, Afghan and Hindu wives.[164] Writing in the 11th century AD, Al-Biruni in his Tarikh al Hind, In the western frontier mountains of India there live various tribes of the Afghans, and extend up to the neighbourhood of the Sindh Valley,[119][165] It was reported that between 1039 and 1040 CE Mas'ud I of the Ghaznavid Empire sent his son to subdue a group of rebel Afghans near Ghazni. An army of Arabs, Afghans, Khiljis and others was assembled by Arslan Shah Ghaznavid in 1119 CE. Another army of Afghans and Khiljis was assembled by Bahram Shah Ghaznavid in 1153 CE. Muhammad of Ghor, ruler of the Ghorids, also had Afghans in his army along with others.[166] A famous Moroccan travelling scholar, Ibn Battuta, visiting Afghanistan following the era of the Khalji dynasty in early 1300s gives his description of the Afghans.

"We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans. They hold mountains and defiles and possess considerable strength, and are mostly highwaymen. Their principle mountain is called Kuh Sulayman. It is told that the prophet Sulayman (Solomon), Sulemani ascended this mountain and having looked out over India, which was then covered with darkness, returned without entering it."[167]

— Ibn Battuta, 1333

Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (Ferishta), writes about Afghans and their country called Afghanistan in the 16th century.

"The men of Kábul and Khilj also went home; and whenever they were questioned about the Musulmáns of the Kohistán (the mountains), and how matters stood there, they said, "Don't call it Kohistán, but Afghánistán; for there is nothing there but Afgháns and disturbances." Thus it is clear that for this reason the people of the country call their home in their own language Afghánistán, and themselves Afgháns. The people of India call them Patán; but the reason for this is not known. But it occurs to me, that when, under the rule of Muhammadan sovereigns, Musulmáns first came to the city of Patná, and dwelt there, the people of India (for that reason) called them Patáns—but God knows!"[168]

— Ferishta, 1560–1620

Anthropology and oral traditions

Pashto is classified under the Eastern Iranian sub-branch of the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Those who speak a Southern dialect of Pashto refer to themselves as Pashtuns, while those who speak Northern Dialect call themselves Pukhtuns. These native people compose the core of ethnic Pashtuns who are found in southeastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan. The Pashtuns have oral and written accounts of their family tree. Lineage is considered very important.

Theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites

Some anthropologists lend credence to the oral traditions of the Pashtun tribes themselves. For example, according to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites is traced to Nimat Allah al-Harawi, who compiled a history for Khan-e-Jehan Lodhi in the reign of Mughal Emperor Jehangir in the 17th century.[169] The 13th century Tabaqat-i Nasiri discusses the settlement of immigrant Bani Israel at the end of the 8th century CE in the Ghor region of Afghanistan, settlement attested by Jewish inscriptions in Ghor. Historian André Wink suggests that the story "may contain a clue to the remarkable theory of the Jewish origin of some of the Afghan tribes which is persistently advocated in the Persian-Afghan chronicles."[170] These references to Bani Israel agree with the commonly held view by Pashtuns that when the twelve tribes of Israel were dispersed, the tribe of Joseph, among other Hebrew tribes, settled in the Afghanistan region.[171] This oral tradition is widespread among the Pashtun tribes. There have been many legends over the centuries of descent from the Ten Lost Tribes after groups converted to Christianity and Islam. Hence the tribal name Yusufzai in Pashto translates to the "son of Joseph". A similar story is told by many historians, including the 14th century Ibn Battuta and 16th century Ferishta.[38] However, the similarity of names can also be traced to the presence of Arabic through Islam.[172]

One conflicting issue in the belief that the Pashtuns descend from the Israelites is that the Ten Lost Tribes were exiled by the ruler of Assyria, while Maghzan-e-Afghani says they were permitted by the ruler to go east to Afghanistan. This inconsistency can be explained by the fact that Persia acquired the lands of the ancient Assyrian Empire when it conquered the Empire of the Medes and Chaldean Babylonia, which had conquered Assyria decades earlier. But no ancient author mentions such a transfer of Israelites further east, or no ancient extra-Biblical texts refer to the Ten Lost Tribes at all.[173]

Some Afghan historians have maintained that Pashtuns are linked to the ancient Israelites. Mohan Lal quoted Mountstuart Elphinstone who wrote:

"The Afghan historians proceed to relate that the children of Israel, both in Ghore and in Arabia, preserved their knowledge of the unity of God and the purity of their religious belief, and that on the appearance of the last and greatest of the prophets (Muhammad) the Afghans of Ghore listened to the invitation of their Arabian brethren, the chief of whom was Khauled...if we consider the easy way with which all rude nations receive accounts favourable to their own antiquity, I fear we much class the descents of the Afghans from the Jews with that of the Romans and the British from the Trojans, and that of the Irish from the Milesians or Brahmins."[174]

— Mountstuart Elphinstone, 1841

This theory has been criticised by not being substantiated by historical evidence.[172] Dr. Zaman Stanizai criticises this theory:[172]

"The ‘mythified’ misconception that the Pashtuns are the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel is a fabrication popularized in 14th-century India. A claim that is full of logical inconsistencies and historical incongruities, and stands in stark contrast to the conclusive evidence of the Indo-Iranian origin of Pashtuns supported by the incontrovertible DNA sequencing that the genome analysis revealed scientifically."

— [172]

According to genetic studies Pashtuns have a greater R1a1a*-M198 modal halogroup than Jews:[175]

"Our study demonstrates genetic similarities between Pathans from Afghanistan and Pakistan, both of which are characterized by the predominance of haplogroup R1a1a*-M198 (>50%) and the sharing of the same modal haplotype...Although Greeks and Jews have been proposed as ancestors to Pathans, their genetic origin remains ambiguous...Overall, Ashkenazi Jews exhibit a frequency of 15.3% for haplogroup R1a1a-M198"

— "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective", European Journal of Human Genetics

Other theories of descent

Some Pashtun tribes claim descent from Arabs, including some claiming to be Sayyids (descendants of Muhammad).[176] Some groups from Peshawar and Kandahar believe to be descended from Greeks who arrived with Alexander the Great.[177] According to Firasat et al. 2007, only a small proportion of Pashtuns may descend from Greeks, but they also suggest that Greek ancestry may also have come from Greek slaves brought by Xerxes I.[178] Some like the Ghilji[179] also claim Turkish descent having settled in the Hindu Kush area and began to assimilate much of the culture and language of the Pashtun tribes already present there.[180]

One historical account connects the Pashtuns to a possible Ancient Egyptian past but this lacks supporting evidence.[181]

"I have read in the Mutla-ul-Anwar, a work written by a respectable author, and which I procured at Burhanpur, a town of Khandesh in the Deccan, that the Afghans are Copts of the race of the Pharaohs; and that when the prophet Moses got the better of that infidel who was overwhelmed in the Red Sea, many of the Copts became converts to the Jewish faith; but others, stubborn and self-willed, refusing to embrace the true faith, leaving their country, came to India, and eventually settled in the Sulimany mountains, where they bore the name of Afghans."

Henry Walter Bellew (1864) was of the view that the Pashtuns likely have mixed Greek and Rajput roots.[182][183][184] Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire expanded influence on the Pashtuns until 305 BCE when they gave up dominating power to the Indian Maurya Empire as part of an alliance treaty.[185] Vogelsang (2002) suggests that a single origin of the Pashtuns is unlikely but rather they are a tribal confederation.[119]

Modern era

Their modern past stretches back to the Delhi Sultanate, particularly the Hotak dynasty and the Durrani Empire. The Hotaks were Ghilji tribesmen who rebelled against the Safavids and seized control over much of Persia from 1722 to 1729.[186] This was followed by the conquests of Ahmad Shah Durrani who was a former high-ranking military commander under Nader Shah. He created the last Afghan empire that covered most of what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, Indian Punjab, as well as the Kohistan and Khorasan provinces of Iran.[187] After the decline of the Durrani dynasty in the first half of the 19th century under Shuja Shah Durrani, the Barakzai dynasty took control of the empire. Specifically, the Mohamedzai subclan held Afghanistan's monarchy from around 1826 to the end of Zahir Shah's reign in 1973. Former President Hamid Karzai is from the Popalzai tribe of Kandahar.[188]

.jpg.webp)

The Pashtuns in Afghanistan resisted British designs upon their territory and kept the Russians at bay during the so-called "Great Game". By playing the two super powers against each other, Afghanistan remained an independent sovereign state and maintained some autonomy (see the Siege of Malakand). During the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan (1880–1901), Pashtun regions were politically divided by the Durand Line, and what is today western Pakistan fell within British India as a result of the border. In the 20th century, many politically active Pashtun leaders living under British rule of undivided India supported Indian independence, including Ashfaqulla Khan,[189][190] Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, Ajmal Khattak, Bacha Khan and his son Wali Khan (both members of the Khudai Khidmatgar), and were inspired by Mohandas Gandhi's non-violent method of resistance.[191][192] Some Pashtuns also worked in the Muslim League to fight for an independent Pakistan, including Yusuf Khattak and Abdur Rab Nishtar who was a close associate of Muhammad Ali Jinnah.[193]

The Pashtuns of Afghanistan attained complete independence from British political intervention during the reign of Amanullah Khan, following the Third Anglo-Afghan War. By the 1950s a popular call for Pashtunistan began to be heard in Afghanistan and the new state of Pakistan. This led to bad relations between the two nations. The Afghan monarchy ended when President Daoud Khan seized control of Afghanistan from his cousin Zahir Shah in 1973, which opened doors for a proxy war by neighbors and the rise of Marxism. In April 1978, Daoud Khan was assassinated along with his family and relatives. Mujahideen commanders began being recruited in neighboring Pakistan for a guerrilla warfare against the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan - the Marxist government was also dominated by Pashtun Khalqists. In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded its southern neighbor Afghanistan in order to defeat a rising insurgency. The mujahideen were funded by the United States, Saudi Arabia, China and others, and included some Pashtun commanders such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Jalaluddin Haqqani. In the meantime, millions of Pashtuns fled their native land to live among other Afghan diaspora in Pakistan and Iran, and from there tens of thousands proceeded to North America, the European Union, the Middle East, Australia and other parts of the world.[99]

In politics and media

Many high-ranking government officials in Afghanistan are Pashtuns, including: Zalmay Rasoul, Abdul Rahim Wardak, Omar Zakhilwal, Ghulam Farooq Wardak, Anwar ul-Haq Ahady, Yousef Pashtun and Amirzai Sangin. The list of current governors of Afghanistan, as well as the parliamentarians in the House of the People and House of Elders, include large percentage of Pashtuns. The Chief of staff of the Afghan National Army, Sher Mohammad Karimi, and Commander of the Afghan Air Force, Mohammad Dawran, as well as Chief Justice of Afghanistan Abdul Salam Azimi and Attorney General Mohammad Ishaq Aloko also belong to the Pashtun ethnic group.

Pashtuns not only played an important role in South Asia but also in Central Asia and the Middle East. Many of the non-Pashtun groups in Afghanistan have adopted the Pashtun culture and use Pashto as a second language. For example, many leaders of non-Pashtun ethnic groups in Afghanistan practice Pashtunwali to some degree and are fluent in Pashto language. These include Ahmad Shah Massoud, Ismail Khan, Mohammed Fahim, Bismillah Khan Mohammadi, and many others. The Afghan royal family, which was represented by King Zahir Shah, belongs to the Mohammadzai tribe of Pashtuns. Other prominent Pashtuns include the 17th-century poets Khushal Khan Khattak and Rahman Baba, and in contemporary era Afghan Astronaut Abdul Ahad Mohmand, former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Zalmay Khalilzad, and Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai among many others.

Many Pashtuns of Pakistan and India have adopted non-Pashtun cultures, and learned other languages such as Urdu, Punjabi, and Hindko.[194] These include Ghulam Mohammad (first Finance Minister, from 1947 to 1951, and third Governor-General of Pakistan, from 1951 to 1955),[195][196][197][198][199] Ayub Khan, who was the second President of Pakistan, and Zakir Husain, who was the third President of India. Many more held high government posts, such as Fazal-ur-Rehman, Asfandyar Wali Khan, Mahmood Khan Achakzai, Sirajul Haq, and Aftab Ahmad Sherpao, who are presidents of their respective political parties in Pakistan. Others became famous in sports (e.g., Imran Khan, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, Younis Khan, Shahid Afridi, Irfan Pathan, Jahangir Khan, Jansher Khan, Rashid Khan, and Mujeeb Ur Rahman) and literature (e.g., Ghani Khan, Hamza Shinwari, and Kabir Stori). Malala Yousafzai, who became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize recipient in 2014, is a Pakistani Pashtun.

Many of the Bollywood film stars in India have Pashtun ancestry; some of the most notable ones are Aamir Khan, Shahrukh Khan, Salman Khan, Feroz Khan, Madhubala, Kader Khan, Saif Ali Khan, Soha Ali Khan, Sara Ali Khan, and Zarine Khan. In addition, one of India's former presidents, Zakir Hussain, belonged to the Afridi tribe.[200][201][202] Mohammad Yunus, India's former ambassador to Algeria and advisor to Indira Gandhi, is of Pashtun origin and related to the legendary Bacha Khan.[203][204][205][206]

Conflicts of Afghanistan

The wars in Afghanistan altered the balance of power in the country - Pashtuns were historically dominant in the country, but the emergence of well-organized armed groups consisting of Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras, combined with politically fragmented Pashtuns, reduced their influence on the state. In 1992, following the mujahideen victory, Burhanuddin Rabbani became the first non-Pashtun President in Afghanistan.[207]

In the late 1990s, Pashtuns were the primary ethnic group in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (Taliban regime).[208] The Northern Alliance that was fighting against the Taliban also included a number of Pashtuns. Among them were Abdullah Abdullah, Abdul Qadir and his brother Abdul Haq, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, Asadullah Khalid, Hamid Karzai and Gul Agha Sherzai. The Taliban regime was ousted in late 2001 during the US-led War in Afghanistan and replaced with the Karzai administration.[209] This was followed by the Ghani administration.[210]

The long wars in Afghanistan have led to Pashtuns on both sides of the border gaining a "reputation" for violence. Conflict as well as the Taliban have also led to a decline in traditional Pashtun customs including Pashtun music and poetry. Some activists and intellectuals are trying to rebuild Pashtun intellectualism and its pre-war culture.[211]

Genetics

According to a study from 2012 called "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective", the study from a sample size of 190 showed R1a1a-M198 to be the most dominant haplogroup in Pashtuns at 67.4%. In the north, it peaks at 50% while in the south, it peaks at 65.8%.[212] R1a-Z2125 occurs at a frequency of 40% in Pashtuns from Northern Afghanistan.[213] This subclade is also predominantly present among Tajik, Turkmen, Uzbek, and Bashkir ethnic groups,[213] as well as in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.[214]

Haplogroup G-M201 reaches 14.7% in Afghan Pashtuns and is the second most frequent haplogroup in Pashtuns from southern Afghanistan. It is virtually absent from all other Afghan populations. This haplogroup is reported at high frequencies in the Caucasus and is thought to be associated with the Neolithic expansion throughout the region.[212][215]

Haplogroup L-M20 exhibits substantial disparity in its distribution on either side of the Hindu Kush range, with 25% of Pashtuns from northern Afghanistan belonging to this lineage, compared with only 4.8% of males from the south. Paragroup L3*-M357 accounts for the majority of L-M20 chromosomes among Afghan Pashtuns in both the north and south.[212]

According to a Mitochondrial DNA analysis of four ethnic groups of Afghanistan, the majority of mtDNA among Afghan Pashtuns belongs to West Eurasian lineages, and share a greater affinity with West Eurasian and Central Asian populations rather than to populations of South Asia or East Asia. The haplogroup analysis indicates the Pashtuns and Tajiks share some sort of ancestral heritage. The study also states that among the studied ethnic groups, the Pashtuns have the greatest HVS-I sequence diversity.[216]

A 2019 study on autosomal STR profiles of the populations of South and North Afghanistan states:[217]

"We observe an overall topology that reflects the general partitioning patterns seen in the MDS plot with the Afghan groups exhibiting close genetic affinities to Near Eastern groups"

Definitions

Among historians, anthropologists, and the Pashtuns themselves, there is some debate as to who exactly qualifies as a Pashtun. The most prominent views are:

- Pashtuns are predominantly an Eastern Iranian people, who use Pashto as their first language, and originate from Afghanistan and Pakistan. This is the generally accepted academic view.

- They are those who follow Pashtunwali.[218]

- Pashtuns are those whose related through patrilineal descent. This may be traced back to legendary times, in accordance with the legend of Qais Abdur Rashid, the figure regarded as their progenitor in folklore.

These three definitions may be described as the ethno-linguistic definition, the religious-cultural definition and the patrilineal definition, respectively.

Ethnic

The ethno-linguistic definition is the most prominent and accepted view as to who is and is not a Pashtun.[219] Generally, this most common view holds that Pashtuns are defined within the parameters of having mainly eastern Iranian ethnic origins, sharing a common language, culture and history, living in relatively close geographic proximity to each other, and acknowledging each other as kinsme. Thus, tribe that speak disparate yet mutually intelligible dialects of Pashto acknowledge each other as ethnic Pashtuns, and even subscribe to certain dialects as "proper", such as the Pukhto spoken by the Yusufzai, Gigyani tribe, Ghilji and other tribes in Eastern Afghanistan and the Pashto spoken by the Kakar, Wazir, Khilji and Durranis in Southern Afghanistan. These criteria tend to be used by most Pashtuns in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Durrani and Ghilji Pashtuns

The Durranis and Ghiljis (or Ghilzais) are the two largest groups of Pashtuns, with approximately two-thirds of Afghan Pashtuns belonging to these confederations.[220] The Durrani tribe has been more urban and politically successful, while the Ghiljis are larger, more rural, and apparently tougher. In the 18th century, the two collaborated at times and at other times fought each other. With a few gaps, Durranis ruled modern Afghanistan continuously until the Saur Revolution of 1978; the new communist rulers were Ghilji.[221]

Tribal allegiances are stronger among the Ghilji, while governance of the Durrani confederation is more to do with cross-tribal structures of land ownership.[220]

Cultural

The cultural definition requires Pashtuns to adhere to Pashtunwali codes.[222] Orthodox tribesmen, may refuse to recognise any non-Muslim as a Pashtun. However, others tend to be more flexible and sometimes define who is Pashtun based on cultural and not religious criteria: Pashtun society is not homogenous by religion. The overwhelming majority of Pashtuns are Sunni, with a tiny Shia community (the Turi and partially the Bangash tribe) in the Kurram and Orakzai agencies of FATA, Pakistan. There are also Hindu Pashtuns, sometimes known as the Sheen Khalai, who have moved predominantly to India.[223][224]

Ancestral

The patrilineal definition is based on an important orthodox law of Pashtunwali which mainly requires that only those who have a Pashtun father are Pashtun. This law has maintained the tradition of exclusively patriarchal tribal lineage. This definition places less emphasis on what language one speaks, such as Pashto, Dari, Hindko, Urdu, Hindi or English.[225] There are various communities who claim Pashtun origin but are largely found among other ethnic groups in the region who generally do not speak the Pashto language. These communities are often considered overlapping groups or are simply assigned to the ethno-linguistic group that corresponds to their geographic location and mother tongue. The Niazi is one of these groups.

Claimants of Pashtun heritage in South Asia have mixed with local Muslim populations and are referred to as Pathan, the Hindustani form of Pashtun.[226][227] These communities are usually partial Pashtun, to varying degrees, and often trace their Pashtun ancestry through a paternal lineage. The Pathans in India have lost both the language and presumably many of the ways of their ancestors, but trace their fathers' ethnic heritage to the Pashtun tribes. Smaller number of Pashtuns living in Pakistan are also fluent in Hindko, Seraiki and Balochi. These languages are often found in areas such as Abbottabad, Mansehra, Haripur, Attock, Khanewal, Multan, Dera Ismail Khan and Balochistan. Some Indians claim descent from Pashtun soldiers who settled in India by marrying local women during the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent.[78] No specific population figures exist, as claimants of Pashtun descent are spread throughout the country. Notably, the Rohillas, after their defeat by the British, are known to have settled in parts of North India and intermarried with local ethnic groups. They are believed to have been bilingual in Pashto and Urdu until the mid-19th century. Some Urdu-speaking Muhajir people of India claiming descent from Pashtuns began moving to Pakistan in 1947. Many Pathans chose to live in the Republic of India after the partition of India and Khan Mohammad Atif, a professor at the University of Lucknow, estimates that "The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan".[228]

During the 19th century, when the British were accepting peasants from British India as indentured servants to work in the Caribbean, South Africa and other far away places, Rohillas who had lost their empire were unemployed and restless were sent to places as far as Trinidad, Surinam, Guyana, and Fiji, to work with other Indians on the sugarcane fields and perform manual labour.[229] Many of these immigrants stayed there and formed unique communities of their own. Some of them assimilated with the other South Asian Muslim nationalities to form a common Indian Muslim community in tandem with the larger Indian community, losing their distinctive heritage. Their descendants mostly speak English and other local languages. Some Pashtuns travelled to as far away as Australia during the same era.[230]

Language

Pashto is the mother tongue of Pashtuns.[231][232][233] It is one of the two national languages of Afghanistan.[234][235] In Pakistan, although being the second-largest language being spoken,[236] it is often neglected officially in the education system.[237][238][239][240][241][242] This has been criticised as adversely impacting the economic advancement of Pashtuns,[243][244] as students do not have the ability to comprehend what is being taught in other languages fully.[245] Robert Nichols remarks:[246]

The politics of writing Pashto language textbooks in a nationalist environment promoting integration through Islam and Urdu had unique effects. There was no lesson on any twentieth century Pakhtun, especially Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the anti-British, pro-Pakhtun nationalist. There was no lesson on the Pashtun state-builders in nineteenth and twentieth century Afghanistan. There was little or no sampling of original Pashto language religious or historical material.

— Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors, Chapter 8, page 278

Pashto is categorised as an Eastern Iranian language,[247] but a remarkably large number of words are unique to Pashto.[248][249] Pashto morphology in relation to verbs is complex compared to other Iranian languages.[250] In this respect MacKenzie states:[251]

If we compare the archaic structure of Pashto with the much simplified morphology of Persian, the leading modern Iranian language, we see that it stands to its ‘second cousin’ and neighbour in something like the same relationship as Icelandic does to English.

— David Neil MacKenzie

Pashto has a large number of dialects: generally divided into Northern, Southern and Central groups;[252] and also Tarino or Waṇetsi as distinct group.[253][254] As Elfenbein notes: "Dialect differences lie primarily in phonology and lexicon: the morphology and syntax are, again with the exception of Wanetsi, quite remarkably uniform".[255] Ibrahim Khan provides the following classification on the letter ښ: the Northern Western dialect (e.g. spoken by the Ghilzai) having the phonetic value /ç+/, the North Eastern (spoken by the Yusafzais etc.) having the sound /x/, the South Western (spoken by the Abdalis etc.) having /ʂ/ and the South Eastern (spoken by the Kakars etc.) having /ʃ/.[256] He illustrates that the Central dialects, which are spoken by the Karlāṇ tribes, can also be divided on the North /x/ and South /ʃ/ distinction but provides that in addition these Central dialects have had a vowel shift which makes them distinct: for instance /ɑ/ represented by aleph the non-Central dialects becoming /ɔː/ in Banisi dialect.[257]

The first Pashto alphabet was developed by Pir Roshan in the 16th century.[258] In 1958, a meeting of Pashtun scholars and writers from both Afghanistan and Pakistan, held in Kabul, standardised the present Pashto alphabet.[259]

Culture

Pashtun culture is mostly based on Pashtunwali and the usage of the Pashto language. Pre-Islamic traditions, dating back to Alexander's defeat of the Persian Empire in 330 BC, possibly survived in the form of traditional dances, while literary styles and music reflect influence from the Persian tradition and regional musical instruments fused with localised variants and interpretation. Poetry is a big part of Pashtun culture and it has been for centuries.[260]

Pashtun culture is a unique blend of native customs and depending on the region with some influences from Western or Southern Asia. Like other Muslims, Pashtuns celebrate Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr. Pashtuns in Afghanistan also celebrate Nauruz, which is the Persian New Year dating back to Zoroastrianism.[261] The Kabul dialect is used to standardize the present Pashto alphabet.[259]

Pashtunwali

Pashtunwali (Pashto: پښتونولي) refers to an ancient self-governing tribal system that regulates nearly all aspects of Pashtun life ranging from community to personal level. One of the better known tenets is Melmastyā́ (Pashto: مېلمستيا), hospitality and asylum to all guests seeking help. Perceived injustice calls for Badál (Pashto: بدل), swift revenge. Many aspects promote peaceful co-existence, such as Nənawā́te (Pashto: ننواتې), the humble admission of guilt for a wrong committed, which should result in automatic forgiveness from the wronged party. These and other basic precepts of Pashtunwali continue to be followed by many Pashtuns, especially in rural areas.

Another prominent Pashtun institution is the lóya jirgá (Pashto: لويه جرګه) or 'grand council' of elected elders.[262] Most decisions in tribal life are made by members of the jirgá (Pashto: جرګه), which has been the main institution of authority that the largely egalitarian Pashtuns willingly acknowledge as a viable governing body.[263]

Pashto literature and poetry

The majority of Pashtuns use Pashto as their native tongue, believed to belong to the Indo-Iranian language family,[265] and is spoken by up to 60 million people.[266][267] It is written in the Pashto-Arabic script and is divided into two main dialects, the southern "Pashto" and the northern "Pukhto". The language has ancient origins and bears similarities to extinct languages such as Avestan and Bactrian.[268] Its closest modern relatives may include Pamir languages, such as Shughni and Wakhi, and Ossetic.[269] Pashto may have ancient legacy of borrowing vocabulary from neighbouring languages including such as Persian and Vedic Sanskrit. Modern borrowings come primarily from the English language.[270]

Fluency in Pashto is often the main determinant of group acceptance as to who is considered a Pashtun. Pashtun nationalism emerged following the rise of Pashto poetry that linked language and ethnic identity. Pashto has national status in Afghanistan and regional status in neighboring Pakistan. In addition to their native tongue, many Pashtuns are fluent in Dari, English and Urdu. Throughout their history, poets, prophets, kings and warriors have been among the most revered members of Pashtun society. Early written records of Pashto began to appear around the 16th century.

The earliest describes Sheikh Mali's conquest of Swat.[271] Pir Roshan is believed to have written a number of Pashto books while fighting with the Mughals. Pashtun scholars such as Abdul Hai Habibi and others believe that the earliest Pashto work dates back to Amir Kror Suri, and they use the writings found in Pata Khazana as proof. Amir Kror Suri, son of Amir Polad Suri, was an 8th-century folk hero and king from the Ghor region in Afghanistan.[272][273] However, this is disputed by several European experts due to lack of strong evidence.

The advent of poetry helped transition Pashto to the modern period. Pashto literature gained significant prominence in the 20th century, with poetry by Ameer Hamza Shinwari who developed Pashto Ghazals.[274] In 1919, during the expanding of mass media, Mahmud Tarzi published Seraj-al-Akhbar, which became the first Pashto newspaper in Afghanistan. In 1977, Khan Roshan Khan wrote Tawarikh-e-Hafiz Rehmatkhani which contains the family trees and Pashtun tribal names. Some notable poets include Khushal Khan Khattak, Afzal Khan Khattak, Ajmal Khattak, Pareshan Khattak, Rahman Baba, Nazo Anaa, Hamza Shinwari, Ahmad Shah Durrani, Timur Shah Durrani, Shuja Shah Durrani, Ghulam Muhammad Tarzi, and Ghani Khan.[275][276]

Recently, Pashto literature has received increased patronage, but many Pashtuns continue to rely on oral tradition due to relatively low literacy rates and education. Pashtun society is also marked by some matriarchal tendencies.[277] Folktales involving reverence for Pashtun mothers and matriarchs are common and are passed down from parent to child, as is most Pashtun heritage, through a rich oral tradition that has survived the ravages of time.

Media and arts

Pashto media has expanded in the last decade, with a number of Pashto TV channels becoming available. Two of the popular ones are the Pakistan-based AVT Khyber and Pashto One. Pashtuns around the world, particularly those in Arab countries, watch these for entertainment purposes and to get latest news about their native areas.[278] Others are Afghanistan-based Shamshad TV, Radio Television Afghanistan, and Lemar TV, which has a special children's show called Baghch-e-Simsim. International news sources that provide Pashto programs include BBC Pashto and Voice of America.

Producers based in Peshawar have created Pashto-language films since the 1970s.

Pashtun performers remain avid participants in various physical forms of expression including dance, sword fighting, and other physical feats. Perhaps the most common form of artistic expression can be seen in the various forms of Pashtun dances. One of the most prominent dances is Attan, which has ancient roots. A rigorous exercise, Attan is performed as musicians play various native instruments including the dhol (drums), tablas (percussions), rubab (a bowed string instrument), and toola (wooden flute). With a rapid circular motion, dancers perform until no one is left dancing, similar to Sufi whirling dervishes. Numerous other dances are affiliated with various tribes notably from Pakistan including the Khattak Wal Atanrh (eponymously named after the Khattak tribe), Mahsood Wal Atanrh (which, in modern times, involves the juggling of loaded rifles), and Waziro Atanrh among others. A sub-type of the Khattak Wal Atanrh known as the Braghoni involves the use of up to three swords and requires great skill. Young women and girls often entertain at weddings with the Tumbal (Dayereh) which is an instrument.[279]

Sports

The Afghanistan national cricket team, which has many Pashtun players, was formed in the early 2000s.[280]

.jpg.webp)

One of the most popular sports among Pashtuns is cricket, which was introduced to South Asia during the early 18th century with the arrival of the British. Many Pashtuns have become prominent international cricketers in the Pakistan national cricket team, including Imran Khan, Shahid Afridi, Majid Khan, Misbah-ul-Haq, Younis Khan,[281] Umar Gul,[282] Junaid Khan,[283] Fakhar Zaman,[284] Mohammad Rizwan,[285] Usman Shinwari and Yasir Shah.[286] Australian cricketer Fawad Ahmed is of Pakistani Pashtun origin who has played for the Australian national team.[287]

Football (soccer) is also one of the most popular sports among Pashtuns. The Former captain and now the current assistant coach of Pakistan national football team, Muhammad Essa, is an ethnic Pashtun. Other sports popular among Pashtuns may include polo, field hockey, volleyball, handball, basketball, golf, track and field, bodybuilding, weightlifting, wrestling (pehlwani), kayaking, horse racing, martial arts, boxing, skateboarding, bowling and chess.

In Afghanistan, the Pashtuns still practice the sport of Buzkashi. The horse-mounted players attempt to place a goat or calf carcass in a goal circle.[288][289][290]

Jahangir Khan and Jansher Khan became professional squash players. Although now retired, they are engaged in promoting the sport through the Pakistan Squash Federation. Maria Toorpakai Wazir is the first female Pashtun squash player. Pakistan also produced other world champions of Pashtun origin: Hashim Khan, Roshan Khan, Azam Khan, Mo Khan and Qamar Zaman.In recent decades Hayatullah Khan Durrani, Pride of Performance legendary caver from Quetta, has been promoting mountaineering, rock climbing and Caving in Balochistan, Pakistan. Mohammad Abubakar Durrani International Canoeing shining star of Pakistan.

Snooker and billiards are played by young Pashtun men, mainly in urban areas where snooker clubs are found. Several prominent international recognized snooker players are from the Pashtun area, including Saleh Mohammed. Although traditionally very less involved in sports than boys, Pashtun girls sometimes play volleyball, basketball, football, and cricket, especially in urban areas.

Makha is a traditional archery sport in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, played with a long arrow (gheshai) having a saucer shaped metallic plate at its distal end, and a long bow.[291]

Religion

Pre-Islamic period

Before the Islamization of their territory, the region used to be home to various beliefs and cults such as Zoroastrianism, ancient Iranian religions, Hinduism and Buddhism.[293][28][294][295] The region of Arachosia, around Kandahar and Quetta in modern-day southern Afghanistan and western Pakistan,[296][297] used to be primarily Zoroastrian and played a key role in the transfer of the Avesta to Persia and is thus considered by some to be the "second homeland of Zoroastrianism".[298][299][300] The Khalaj of Kabul, supposed ancestors of the modern Ghilji Pashtuns,[112][301] used to worship various local ancient Iranian gods such as the fire God Atar.[302][303] The historic region of Gandhara used to be dominantly Hindu and Buddhist.[304] Buddhism, in its own unique syncretic form, was also common throughout the whole region, people would be patrons of Buddhism but still worship local Iranian gods such as Ahura Mazda, Lady Nana, Anahita or Mihr (Mithra).[305][306][307]

In folklore, it is believed that most Pashtuns are descendants of Qais Abdur Rashid, who is purported to have been an early convert to Islam and thus bequeathed the faith to the early Pashtun population.[174] The legend says that after Qais heard of the new religion of Islam, he travelled to meet Muhammad in Medina and returned to Afghanistan as a Muslim. He purportedly had four children: Sarban, Batan, Ghourghusht and Karlan. This theory has been criticised, for not being substantiated by historical evidence and based on post-Arabic influence.[172]

The Muslim conquest of Afghanistan was not completed until the 10th century under Ghaznavid and Ghurid dynasty's rule who patronized Muslim religious institutions.[308] The Caliph Al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833 A.D.) conducted raids against non-Muslim rulers of a Kabul and Zabul.[309] Al-Utbi in Tarikh Yamini states that the Afghans and Khaljis, living between Laghman and Peshawar, took the oath of allegiance to Sabuktigin and were recruited into his army.[310]

Modern era

The overwhelming majority of Pashtuns follow Sunni Islam, belonging to the Hanafi school of thought. There are some Shia Pashtun communities in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan and in neighbouring northeastern section of Paktia Province of Afghanistan. The Shias belong to the Turi tribe while the Bangash tribe is approximately 50% Shia and the rest Sunni, who are mainly found in and around the Parachinar, Kurram, Hangu, Kohat and Orakzai areas in Pakistan.[312]

A legacy of Sufi activity may be found in some Pashtun regions, especially in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa area, as evident in songs and dances. Many Pashtuns are prominent Ulema, Islamic scholars, such as Maulana Aazam an author of more than five hundred books including Tafasee of the Quran as Naqeeb Ut Tafaseer, Tafseer Ul Aazamain, Tafseer e Naqeebi and Noor Ut Tafaseer etc., as well as Muhammad Muhsin Khan who has helped translate the Noble Quran, Sahih Al-Bukhari and many other books to the English language.[313] Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani was a 19th-century Islamic ideologist and one of the founders of Islamic modernism. Although his ethnicity is disputed by some, he is widely accepted in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region as well as in the Arab world, as a Pashtun from the Kunar Province of Afghanistan. Like other non Arabic-speaking Muslims, many Pashtuns are able to read the Quran but not understand the Arabic language implicit in the holy text itself. Translations, especially in English, are scarcely far and in between understood or distributed. This paradox has contributed to the spread of different versions of religious practices and Wahabism, as well as political Islamism (including movements such as the Taliban) having a key presence in Pashtun society. In order to counter radicalisation and fundamentalism, the United States began spreading its influence in Pashtun areas.[314][315] Many Pashtuns want to reclaim their identity from being lumped in with the Taliban and international terrorism, which is not directly linked with Pashtun culture and history.[316]

Lastly, little information is available on non-Muslim as there is limited data regarding irreligious groups and minorities, especially since many of the Hindu and Sikh Pashtuns migrated from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after the partition of India and later, after the rise of the Taliban.[23][317]

A small Pashtun Hindu community, known as the Sheen Khalai meaning 'blue skinned' (referring to the color of Pashtun women's facial tattoos), migrated to Unniara, Rajasthan, India after partition.[24] Prior to 1947, the community resided in the Quetta, Loralai and Maikhter regions of the British Indian province of Baluchistan.[318][24][25] They are mainly members of the Pashtun Kakar tribe. Today, they continue to speak Pashto and celebrate Pashtun culture through the Attan dance.[318][24]

There is also a minority of Pashtun Sikhs in some tribal areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including in Tirah, Orakzai, Kurram, Malakand, and Swat. Due to the ongoing insurgency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, like many other tribal Pashtuns, some Pashtun Sikhs were internally displaced from their ancestral villages to settle in cities like Peshawar and Nankana Sahib.[26][319][320]

Women

_%E2%80%93_kobiety_%E2%80%9Ekuczi%E2%80%9D_-_mi%C4%99dzy_Heratem_a_Giriszk_nad_rzek%C4%85_Galamieh_-_001076n.jpg.webp)

_Cropped.jpg.webp)

In Pashtun society there are three levels of women's leadership and legislative authority: the national level, the village level, and the family level. The national level includes women such as Nazo Tokhi (Nazo Anaa), Zarghona Anaa, and Malalai of Maiwand. Nazo Anaa was a prominent 17th century Pashto poet and an educated Pashtun woman who eventually became the "Mother of Afghan Nationalism" after gaining authority through her poetry and upholding of the Pashtunwali code. She used the Pashtunwali law to unite the Pashtun tribes against their Persian enemies. Her cause was picked up in the early 18th century by Zarghona Anaa, the mother of Ahmad Shah Durrani.[321]

The lives of Pashtun women vary from those who reside in conservative rural areas, such as the tribal belt, to those found in relatively freer urban centres.[322] At the village level, the female village leader is called "qaryadar". Her duties may include witnessing women's ceremonies, mobilising women to practice religious festivals, preparing the female dead for burial, and performing services for deceased women. She also arranges marriages for her own family and arbitrates conflicts for men and women.[321] Though many Pashtun women remain tribal and illiterate, others have become educated and gainfully employed.[322]

In Afghanistan, the decades of war and the rise of the Taliban caused considerable hardship among Pashtun women, as many of their rights were curtailed by a rigid interpretation of Islamic law. The difficult lives of Afghan female refugees gained considerable notoriety with the iconic image Afghan Girl (Sharbat Gula) depicted on the June 1985 cover of National Geographic magazine.[323]

Modern social reform for Pashtun women began in the early 20th century, when Queen Soraya Tarzi of Afghanistan made rapid reforms to improve women's lives and their position in the family. She was the only woman to appear on the list of rulers in Afghanistan. Credited with having been one of the first and most powerful Afghan and Muslim female activists. Her advocacy of social reforms for women led to a protest and contributed to the ultimate demise of King Amanullah's reign in 1929.[324] In 1942, Madhubala (Mumtaz Jehan), the Marilyn Monroe of India, entered the Bollywood film industry. Bollywood blockbusters of the 1970s and 1980s starred Parveen Babi, who hailed from the lineage of Gujarat's historical Pathan community: the royal Babi Dynasty. Other Indian actresses and models, such as Zarine Khan, continue to work in the industry.[45] Civil rights remained an important issue during the 1970s, as feminist leader Meena Keshwar Kamal campaigned for women's rights and founded the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) in the 1977.[325]

Pashtun women these days vary from the traditional housewives who live in seclusion to urban workers, some of whom seek or have attained parity with men.[322] But due to numerous social hurdles, the literacy rate remains considerably lower for Pashtun females than for males.[326] Abuse against women is present and increasingly being challenged by women's rights organisations which find themselves struggling with conservative religious groups as well as government officials in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. According to a 1992 book, "a powerful ethic of forbearance severely limits the ability of traditional Pashtun women to mitigate the suffering they acknowledge in their lives."[327]

Despite obstacles, many Pashtun women have begun a process of slow change. A rich oral tradition and resurgence of poetry has inspired many Pashtun women seeking to learn to read and write.[277] Further challenging the status quo, Vida Samadzai was selected as Miss Afghanistan in 2003, a feat that was received with a mixture of support from those who back the individual rights of women and those who view such displays as anti-traditionalist and un-Islamic. Some Pashtun women have attained political office in Pakistan. In Afghanistan, following recent elections, the proportion of female political representatives is one of the highest in the world.[328] A number of Pashtun women are found as TV hosts, journalists and actors.[55] Khatol Mohammadzai serves as Brigadier general in the military of Afghanistan, another Pashtun female became a fighter pilot in the Pakistan Air Force.[329] Some other notable Pashtun women include Suhaila Seddiqi, Zeenat Karzai, Shukria Barakzai, Fauzia Gailani, Naghma, Najiba Faiz, Tabassum Adnan, Sana Safi, Malalai Kakar, Malala Yousafzai, and the late Ghazala Javed.

Pashtun women often have their legal rights curtailed in favour of their husbands or male relatives. For example, though women are officially allowed to vote in Afghanistan and Pakistan, some have been kept away from ballot boxes by males.[330] Another tradition that persists is swara (a form of child marriage), which was declared illegal in Pakistan in 2000 but continues in some parts.[331] Substantial work remains for Pashtun women to gain equal rights with men, who remain disproportionately dominant in most aspects of Pashtun society. Human rights organisations continue to struggle for greater women's rights, such as the Afghan Women's Network and the Aurat Foundation in Pakistan which aims to protect women from domestic violence.

Notable people

- Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Durrani Empire. Defeated the Maratha Empire at the Third Battle of Panipat. He is considered to be the founder of modern-day Afghanistan.[332]

- Timur Shah Durrani, second ruler of the Durrani Empire, defeated Sikhs and took back Multan.

- Mirwais Hotak, revolted against Safavid Iran and established the Hotak dynasty.

- Mahmud Hotak, second ruler of the Hotaki dynasty and Shah of Persia. He Invaded Persia and overthrew the Safavid dynasty.

- Azad Shah Afghan, military commander famous for conquering parts of Central and Western Iran, as well as Kurdistan and Gilan.

- Hamid Karzai, head of the Popalzai tribe and served as President of Afghanistan from 22 December 2001 to 29 September 2014.

- Mohammad Ashraf Ghani,[333] the previous president Islamic republic of Afghanistan.

- Mohammad Najibullah, Afghan politician[334]

- Gulbuddin Hekmatyar

- Hafizullah Amin

- Mohammed Daoud Khan

- Mohammed Zahir Shah

- Ayub Khan (Hindko Speaker)

- Yahya Khan

- Amanullah Khan

- Shaheen Afridi, Pakistani cricketer.

- Rashid Khan,[335] Afghan cricketer.

- Khalilullah Khalili, Pashtun poet of the Persian language.

- Sher Shah Suri, founder and 16th century ruler of the Sur Empire. Defeated the Mughal Empire at the Battle of Chausa.

- Rahman Baba, Pashto poet and Sufi Dervish.

- Bahlul Lodi, founder and 15th century ruler of the Lodi dynasty.

- Sikandar Lodi, Sultan of the Lodi dynasty. He gained control of Bihar and founded the modern city of Agra.[336]

- Ibrahim Lodi, last Sultan of the Delhi Sultanate.

- Abdul Ahad Momand, first Afghan cosmonaut, made Pashto the 4th language spoken in space

- Khushal Khan Khattak, warrior and Pashto poet.

- Madhubala, Indian actress of Pashtun descent. Famous for her portrayal of Anarkali in the 1960 film Mughal-e-Azam, which was the highest grossing film in India at that point of time.

- Nazo Tokhi, Afghan poetess and writer in the Pashto language. Mother of the 18th century Afghan King Mirwais Hotak.

- Wazir Akbar Khan, Afghan prince, general and emir. Famous for his role in the First Anglo-Afghan War, particularly for the massacre of Elphinstone's army.

- Abdul Ghafoor Breshna, painter, music composer, poet and film director. Breshna is regarded as one of Afghanistan's most talented artists. He is the artist behind the painting 1747 coronation of Ahmad Shah Durrani, sketch of Sher Shah Suri and the Afghan national anthem of the Republic of Afghanistan.

- Malalai of Maiwand, national folk hero of Afghanistan. Rallied Pashtun fighters to defeat the British during the Second Anglo-Afghan war.

- Pir Roshan, warrior, poet, Sufi and revolutionary leader. Created the first known Pashto alphabet. He's also the founder of the Roshani movement/the enlightened movement.

- Hamza Shinwari, prominent Pashto poet. He is considered a bridge between classic Pashto literature and modern literature.

- Abdul Ghani Khan, philosopher, poet, eartist, writer and politician.

- Ahmad Zahir, dubbed the "Elvis of Afghanistan", Ahmad Zahir is considered to be the best singer in Afghanistan's history. Most of his songs are in Persian, albeit he also made many songs in Pashto, Russian, English and Urdu.[337][338][339][340]

- Mirza Mazhar Jan-e-Janaan, renowned Hanafi Maturidi Naqshbandi Sufi poet, distinguished as one of the "four pillars of Urdu poetry".

- Malala Yousafzai, female education activist, awarded the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize at age 17, the first Pashtun to receive a Nobel Prize.

See also

- Pashtun culture

- List of Pashtun empires and dynasties

- Pashto literature and poetry

- Pashtun diaspora

- Pashtun tribes

- Pashtun nationalism

- Pashtunistan

- Pashtunization

- Pashtun colonization of northern Afghanistan

Explanatory notes

- Note: population statistics for Pashtuns (including those without a notation) in foreign countries were derived from various census counts, the UN, the CIA's The World Factbook and Ethnologue.

References

- Lewis, Paul M. (2009). "Pashto, Northern". SIL International. Dallas, TX: Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Ethnic population: 49,529,000 possibly total Pashto in all countries.

- "South Asia :: Pakistan — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "CIA - The World Factbook -- Afghanistan". umsl.edu. 21 June 2022.

- Ali, Arshad (15 February 2018). "Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan's great granddaughter seeks citizenship for 'Phastoons' in India". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

Interacting with mediapersons on Wednesday, Yasmin, the president of All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, said that there were 32 lakh Phastoons in the country who were living and working in India but were yet to get citizenship.

- "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The News International. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. "LANGUAGE INDIA, STATES AND UNION TERRITORIES (Table C-16)" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

AFGHANI/KABULI/PASHTO 21,677

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Pakhtoons in Kashmir". The Hindu. 20 July 1954. Archived from the original on 9 December 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

Over a lakh Pakhtoons living in Jammu and Kashmir as nomad tribesmen without any nationality became Indian subjects on July 17. Batches of them received certificates to this effect from the Kashmir Prime Minister, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, at village Gutligabh, 17 miles from Srinagar.

- "United Arab Emirates: Demography" (PDF). Encyclopædia Britannica World Data. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- 42% of 200,000 Afghan Americans = 84,000 and 15% of 363,699 Pakistani Americans = 54,554. Total Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns in USA = 138,554.

- "Ethnologue report for Southern Pashto: Iran (1993)". SIL International. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Maclean, William (10 June 2009). "Support for Taliban dives among British Pashtuns". Reuters. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- Relations between Afghanistan and Germany Archived 16 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine: Germany is now home to almost 90,000 people of Afghan origin. 42% of 90,000 = 37,800

- "Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada". 2.statcan.ca. 2006. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Perepis.ru". perepis2002.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex – Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2 June 2008. Total responses: 25,451,383 for total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- "Pashtuns in malaysia". Northern Pashtuns in Malaysia.

- "Väestö 31.12. muuttujina Maakunta, Kieli, Ikä, Sukupuoli, Vuosi ja Tiedot". Tilastokeskuksen PX-Web tietokannat.

- Green, Nile (2017). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-29413-4.

Many of the communities of ethnic Pashtuns (known as Pathans in India) that had emerged in India over the previous centuries lived peaceably among their Hindu neighbors. Most of these Indo-Afghans lost the ability to speak Pashto and instead spoke Hindi and Punjabi.

- Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- Williams, Victoria; Taylor, Ken (2017). Etiquette and Taboos around the World: A Geographic Encyclopedia of Social and cultural customs. ABC CLIO. p. 231. ISBN 978-1440838200.

- Nyrop, Richard F; Seekins, Donald M (1986). Afghanistan: A Country Study by United States Department of the Army. United States Department of the Army, American University. p. 105. ISBN 9780160239298.

- Ali, Tariq (2003). The clash of fundamentalisms: crusades, jihads and modernity. Verso. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-85984-457-1. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

The friends from Peshawar would speak of Hindu and Sikh Pashtuns who had migrated to India. In the tribal areas – the no man's land between Afghanistan and Pakistan – quite a few Hindus stayed on and were protected by the tribal codes. The same was true in Afghanistan itself (till the mujahidin and the Taliban arrived).

- Haider, Suhasini (3 February 2018). "Tattooed 'blue-skinned' Hindu Pushtuns look back at their roots". The Hindu. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Khan, Naimat (30 June 2020). "70 years on, one Pashtun town still safeguards its old Hindu-Muslim brotherhood". Arab News.

The meat-eating Hindu Pashtuns are a little known tribe in India even today, with a distinct culture carried forward from Afghanistan and Balochistan which includes blue tattoos on the faces of the women, traditional Pashtun dancing and clothes heavily adorned with coins and embroidery.

- Eusufzye, Khan Shehram (2018). "Two identities, twice the pride: The Pashtun Sikhs of Nankana Saheb". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

One can sense a diminutive yet charming cultural amalgamation in certain localities within the town with the settling of around 250 Pashtun Sikh families in the city.

Ruchi Kumar, The decline of Afghanistan's Hindu and Sikh communities, Al Jazeera, 2017-01-01, "the culture among Afghan Hindus is predominantly Pashtun"

Beena Sarwar, Finding lost heritage, Himal, 2016-08-03, "Singh also came across many non turban-wearing followers of Guru Nanak in Pakistan, all of Pashtun origin and from the Khyber area."