Amman

Amman (English: /əˈmɑːn/; Arabic: عَمَّان, ʻammān pronounced [ʕamːaːn]; Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 Rabat ʻAmān)[5][6] is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center.[7] With a population of 4,061,150 as of 2021, Amman is Jordan's primate city and is the largest city in the Levant region, the fifth-largest city in the Arab world, and the ninth largest metropolitan area in the Middle East.[8]

Amman

عَمَّان | |

|---|---|

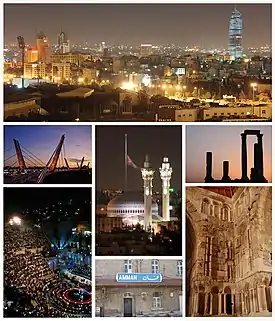

Capital city | |

Amman city, from right to left and from above to below: Abdali Project dominating Amman's skyline, Temple of Hercules on Amman Citadel, King Abdullah I Mosque and Raghadan Flagpole, Abdoun Bridge, Umayyad Palace, Ottoman Hejaz railway station and Roman Theater. | |

Seal | |

| Nicknames: | |

| |

Amman  Amman  Amman  Amman | |

| Coordinates: 31°56′59″N 35°55′58″E | |

| Country | Jordan |

| Governorate | Amman Governorate |

| Municipality | 1909 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Yousef Shawarbeh[3][4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,680 km2 (650 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,100 m (3,600 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 700 m (2,300 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 4,061,150 |

| • Density | 2,380/km2 (6,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Ammani |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| Postal code | 11110-17198 |

| Area code | +962(6) |

| Website | Greater Amman Municipality |

The earliest evidence of settlement in Amman dates to the 8th millennium BC, in a Neolithic site known as 'Ain Ghazal, where the world's oldest statues of the human form have been unearthed. During the Iron Age, the city was known as Rabbath Ammon and served as the capital of the Ammonite Kingdom. In the 3rd century BC, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt, rebuilt the city and renamed it "Philadelphia", making it a regional center of Hellenistic culture. Under Roman rule, Philadelphia was one of the ten Greco-Roman cities of the Decapolis before being directly ruled as part of Arabia Petraea province. The Rashidun Caliphate conquered the city from the Byzantines in the 7th century AD, restored its ancient Semitic name and called it Amman. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, the city alternated between periods of devastation and abandonment and periods of relative prosperity as the center of the Balqa region. Amman was largely abandoned from the 15th century until 1878, when Ottoman authorities began settling Circassians there.

Amman's first municipal council was established in 1909.[9] Amman witnessed rapid growth after its designation as Transjordan's capital in 1921, receiving migrations from different Jordanian and Levantine cities, and after several successive waves of refugees: Palestinians in 1948 and 1967; Iraqis in 1990 and 2003; and Syrians since 2011. It was initially built on seven hills but now spans over 19 hills combining 22 areas,[9] which are administered by the Greater Amman Municipality.[10] Areas of Amman have gained their names from either the hills (Jabal) or the valleys (Wadi) they occupy, such as Jabal Lweibdeh and Wadi Abdoun.[9] East Amman is predominantly filled with historic sites that frequently host cultural activities, while West Amman is more modern and serves as the economic center of the city.[11]

Approximately one million visitors arrived in Amman in 2018, which made it the 89th most-visited city in the world and the 12th most-visited Arab city. Amman has a relatively fast growing economy,[12] and it is ranked as a Beta− global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[13] Moreover, it was named one of the Middle East and North Africa's best cities according to economic, labor, environmental, and socio-cultural factors.[14] The city is among the most popular locations in the Arab world for multinational corporations to set up their regional offices, alongside Doha and only behind Dubai.[15] The city is served by the Amman Bus and the Amman Bus Rapid Transit public transportation systems. Another BRT system under-construction will connect the city to nearby Zarqa.

Etymology

Amman derives its name from the ancient people of the Ammonites, whose capital the city has been since the 13th century BCE. The Ammonites named it 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍, Rabbat ʻAmmān,[5] with the term Rabbat meaning the "Capital" or the "King's Quarters". In the Hebrew Bible, Rabbat ʻAmmān is referred to as "Rabbat Bnei ʿAmmon" (Biblical Hebrew: רבת בני עמון, Tiberian Hebrew Rabbaṯ Bəne ʿAmmôn), shortened in Modern Hebrew to "Rabbat Ammon" , and appears in English translations as "Rabbath Ammon". Over time, the term "Rabbat" was no longer used and the influence of new civilizations that conquered the city gradually changed its name to "Amman".[16]

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Macedonian ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who reigned from 283 to 246 BC, renamed the city to "Philadelphia" (Ancient Greek: Φιλαδέλφεια; literally: "brotherly love") after occupying it. The name was given as an adulation to his own nickname, Philadelphus.[17]

History

Neolithic period

The Neolithic site of 'Ain Ghazal was found in the outskirts of Amman. At its height, around 7000 BC, it had an area of 15 hectares (37 acres) and was inhabited by ca. 3000 people (four to five times the population of contemporary Jericho). At that time the site was a typical aceramic Neolithic village. Its houses were rectangular mud-bricked buildings that included a main square living room, whose walls were made up of lime plaster.[19] The site was discovered in 1974 as construction workers were working on a road crossing the area. By 1982, when the excavations started, around 600 meters (2,000 feet) of road ran through the site. Despite the damage brought by urban expansion, the remains of 'Ain Ghazal provided a wealth of information.[20]

'Ain Ghazal is well known for a set of small human statues found in 1983, when local archeologists stumbled upon the edge of a large pit 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) containing them.[21] These statues are human figures made with white plaster, with painted clothes, hair, and in some cases ornamental tattoos. Thirty-two figures were found in two caches, fifteen of them full figures, fifteen busts, and two fragmentary heads. Three of the busts were two-headed, the significance of which is not clear.[20]

Iron Age: the Ammonites

In the 13th century BC Amman was the capital of the Ammonites, and became known as "Rabbah" or "Rabbath Ammon". Ammon provided several natural resources to the region, including sandstone and limestone, along with a productive agricultural sector that made Ammon a vital location along the King's Highway, the ancient trade route connecting Egypt with Mesopotamia, Syria and Anatolia. As with the Edomites and Moabites, trade along this route gave the Ammonites considerable revenue.[22] Milcom is named in the Hebrew Bible as the national god of Ammon. Another ancient deity, Moloch, usually associated with the use of children as offerings, is also mentioned in the Bible as a god of Ammon, but this is probably a mistake for Milcom. However, excavations by archeologists near Amman Civil Airport uncovered a temple, which included an altar containing many human bone fragments. The bones showed evidence of burning, which led to the assumption that the altar functioned as a pyre and used for human sacrifice.[23]

Amman is mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible as Rabbat' Bnei 'Amon (Hebrew: רבת בני עמון) or Rabbah (Hebrew: רבה). According to the biblical narrative, the Ammonite king Hanun allied with Hadadezer king of Aram-Zobah against the United Kingdom of Israel. During the war, Joab, the captain of King David's army, laid siege to Rabbah, Hanun's royal capital, and destroyed it (2 Samuel 12:26–28, 1 Chronicles 20:1–2). David took a great quantity of plunder from the city, including the king's crown, and brought it to his capital, Jerusalem (2 Samuel 12:29–31). Hanun's brother, Shobi, was made king in his place, and became a loyal vassal of David (2 Samuel 17:27). Hundreds of years later, the prophet Jeremiah foresaw the coming destruction and final desolation of the city (Jeremiah 49:2).

Today, several Ammonite ruins across Amman exist, such as Rujm Al-Malfouf and some parts of the Amman Citadel. The ruins of Rujm Al-Malfouf consist of a stone watchtower used to ensure protection of their capital and several store rooms to the east.[24][25]

The city was later conquered by the Assyrians, followed by the Babylonians and the Achaemenid Persians.

Classical period: Philadelphia

Conquest of the Middle East and Central Asia by Alexander the Great firmly consolidated the influence of Hellenistic culture.[26] The Greeks founded new cities in the area of modern-day Jordan, including Umm Qays, Jerash and Amman. Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Macedonian ruler of Egypt, who occupied and rebuilt the city, named it "Philadelphia" (Ancient Greek: Φιλαδέλφεια), evoking "brotherly love" in Greek. The name was given as an adulation to his own nickname, Philadelphus.[27]

One of the most original monuments in Jordan, and perhaps in the Hellenistic period in the Near East, is the village of Iraq al-Amir in the valley of Wadi as-Sir, southwest of Amman, which is home to Qasr al-Abd ('Castle of the Slave'). Other nearby ruins include a village, an isolated house and a fountain, all of which are barely visible today due to the damage brought by a major earthquake that hit the region in the year 362.[28] Qasr al-Abd is believed to have been built by Hyrcanus of Jerusalem, who was the head of the powerful Jewish Tobiad family. Shortly after he began the construction of that large building, in c. 170-168 BC, upon returning from a military campaign in Egypt, Antiochus IV conquered Jerusalem, ransacked the Second Temple where the treasure of Hyrcanus was kept, and appeared determined to attack Hyrcanus. Upon hearing this, Hyrcanus committed suicide,[29] leaving his palace in Philadelphia uncompleted.[29]

The Tobiads fought the Arab Nabateans for twenty years until they lost the city to them. After losing Philadelphia, we no longer hear of the Tobiad family in written sources.[30]

The Romans conquered much of the Levant in 63 BC, inaugurating a period of Roman rule that lasted for four centuries. In the northern modern-day Jordan, the Greek cities of Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa, Gedara, Pella and Arbila joined with other cities in Palestine and Syria; Scythopolis, Hippos, Capitolias, Canatha and Damascus to form the Decapolis League, a fabled confederation linked by bonds of economic and cultural interest.[30] Philadelphia became a point along a road stretching from Ailah to Damascus that was built by Emperor Trajan in AD 106. This provided an economic boost for the city in a short period of time.[31]

Roman rule in Jordan left several ruins across the country, some of which exist in Amman, such as the Temple of Hercules at the Amman Citadel, the Roman Theatre, the Odeon, and the Nymphaeum. The two theaters and the nymphaeum fountain were built during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius around AD 161. The theatre was the larger venue of the two and had a capacity for 6,000 attendees. It was oriented north and built into the hillside, to protect the audience from the sun. To the northeast of the theatre was a small odeon. Built at roughly the same time as the theatre, the Odeon had 500 seats and is still in use today for music concerts. Archaeologists speculate that the structure was originally covered with a wooden roof to shield the audience from the weather. The Nymphaeum is situated southwest of the Odeon and served as Philadelphia's chief fountain. The Nymphaeum is believed to have contained a 600 square meters (6,500 sq ft) pool which was 3 meters (9.8 ft) deep and was continuously refilled with water.[32]

During the late Byzantine period in the seventh century, several bishops and churches were based in the city.[31]

Islamic Amman (7th-15th century)

In the 630s, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered the region from the Byzantines, beginning the Islamic era in the Levant. Philadelphia was renamed "Amman" by the Muslims and became part of the district of Jund Dimashq. A large part of the population already spoke Arabic, which facilitated integration into the caliphate, as well as several conversions to Islam. Under the Umayyad caliphs who began their rule in 661 AD, numerous desert castles were established as a means to govern the desert area of modern-day Jordan, several of which are still well-preserved. Amman had already been functioning as an administrative centre. The Umayyads built a large palace on the Amman Citadel hill, known today as the Umayyad Palace. Amman was later destroyed by several earthquakes and natural disasters, including a particularly severe earthquake in 747. The Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids three years later.[30]

Amman's importance declined by the mid-8th century after damage caused by several earthquakes rendered it uninhabitable.[33] Excavations among the collapsed layer of the Umayyad Palace have revealed remains of kilns from the time of the Abbasids (750–969) and the Fatimids (969–1099).[34] In the late 9th century, Amman was noted as the "capital" of the Balqa by geographer al-Yaqubi.[35] Likewise, in 985, the Jerusalemite historian al-Muqaddasi described Amman as the capital of Balqa,[35] and that it was a town in the desert fringe of Syria surrounded by villages and cornfields and was a regional source of lambs, grain and honey.[36] Furthermore, al-Muqaddasi describes Amman as a "harbor of the desert" where Arab Bedouin would take refuge, and that its citadel, which overlooked the town, contained a small mosque.[37]

The occupation of the Citadel Hill by the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem is so far based only on interpretations of Crusader sources. William of Tyre writes in his Historia that in 1161 Philip of Milly received the castle of Ahamant, which is seen to refer to Amman, as part of the lordship of Oultrejordain.[38] In 1166 Philip joined the military order of the Knights Templar, passing on to them a significant part of his fief including the castle of Ahamant[39] or "Haman", as it is named in the deed of confirmation issued by King Amalric.[40] By 1170, Amman was in Ayyubid hands.[41] The remains of a watch tower on Citadel Hill, first attributed to the Crusaders, now are preferentially dated to the Ayyubid period, leaving it to further research to find the location of the Crusader castle.[40] During the Ayyubid period, the Damascene geographer al-Dimashqi wrote that Amman was part of the province of al-Karak, although "only ruins" remained of the town.[42]

During the Mamluk era (late 13th–early 16th centuries), the region of Amman was a part of Wilayat Balqa, the southernmost district of Mamlakat Dimashq (Damascus Province).[43] The capital of the district in the first half of the 14th century was the minor administrative post of Hisban, which had a considerably smaller garrison than the other administrative centers in Transjordan, namely Ajlun and al-Karak.[44] In 1321, the geographer Abu'l Fida, recorded that Amman was "a very ancient town" with fertile soil and surrounded by agricultural fields.[37] For unclear, though likely financial reasons, in 1356, the capital of Balqa was transferred from Hisban to Amman, which was considered a madina (city).[45] In 1357, Emir Sirghitmish bought Amman in its entirety, most likely to use revenues from the city to help fund the Madrasa of Sirghitmish, which he built in Cairo that same year.[45] After his purchase of the city, Sirghitmish transferred the courts, administrative bureaucracy, markets and most of the inhabitants of Hisban to Amman.[45] Moreover, he financed new building works in the city.[45]

Ownership of Amman following Sirghitmish's death in 1358 passed to successive generations of his descendants until 1395, when his descendants sold it to Emir Baydamur al-Khwarazmi, the na'ib as-saltana (viceroy) of Damascus.[45] Afterward, part of Amman's cultivable lands were sold to Emir Sudun al-Shaykhuni (died 1396), the na'ib as-saltana of Egypt.[46] The increasingly frequent division and sale of the city and lands of Amman to different owners signalled declining revenues coming from Amman, while at the same time, Hisban was restored as the major city of the Balqa in the 15th century.[47] From then until 1878, Amman was an abandoned site periodically used to shelter seasonal farmers who cultivated arable lands in its vicinity and by Bedouin tribes who used its pastures and water.[48][49] The Ottoman Empire annexed the region of Amman in 1516, but for much of the Ottoman period, al-Salt functioned as the virtual political center of Transjordan.

Modern Amman (1878-today)

Amman began to be resettled in 1878, when several hundred Muslim Circassians arrived following their expulsion from the formerly Ottoman Balkans.[50] Between 1878 and 1910, tens of thousands of Circassians had relocated to Ottoman Syria after being displaced by the Russian Empire during the events of the Russo-Circassian War.[51] The Ottoman authorities directed the Circassian, who were mainly of peasant stock, to settle in Amman, and distributed arable land among them.[52] Their settlement was a partial manifestation of the Ottoman statesman Kamil Pasha's project to establish a vilayet centered in Amman, which, along with other sites in its vicinity, would become Circassian-populated townships guaranteeing the security of the Damascus–Medina highway.[53] The first Circassian settlers, who belonged to the Shapsug dialect group,[54] lived near Amman's Roman theater and incorporated its stones into the houses they built.[50] The English traveller Laurence Oliphant noted in his 1879 visit that most of the original Circassian settlers had left Amman by then, with about 150 remaining.[54] They were joined by Circassians from the Kabardian and Abzakh groups in 1880–1892.[54]

.jpg.webp)

Until 1900 settlement was concentrated in the valley and slopes of the Amman stream and settlers built mud-brick houses with wooden roofs.[54] The French Dominican priest Marie-Joseph Lagrange commented in 1890 about Amman: "A mosque, the ancient bridges, all that jumbled with the houses of the Circassians gives Amman a remarkable physiognomy".[54] The new village became a nahiye (subdistrict) center of the kaza of al-Salt in the Karak Sanjak established in 1894.[54] By 1908 Amman contained 800 houses divided between three main quarters, Shapsug, Kabartai and Abzakh, each called after the Circassian groupings which respectively settled there, a number of mosques, open-air markets, shops, bakeries, mills, a textile factory, a post and telegraph office and a government compound (saraya).[54] Kurdish settlers formed their own quarter called "al-Akrad" after them, while a number of townspeople from nearby al-Salt and al-Fuheis, seeking to avoid high taxes and conscription or attracted by financial incentives, and traders from Najd and Morocco, had also moved to the town.[56]

The city's demographics changed dramatically after the Ottoman government's decision to construct the Hejaz Railway, which linked Damascus and Medina, and facilitated the annual Hajj pilgrimage and trade. Operational in central Transjordan since 1903, the Hejaz Railway helped to transform Amman from a small village into a major commercial hub in the region. Circassian entrepreneurship, facilitated by the railway, helped to attract investment from merchants from Damascus, Nablus, and Jerusalem, many of whom moved to Amman in the 1900s and 1910s.[50]

Amman's first municipal council was established in 1909, and Circassian Ismael Babouk was elected as its mayor.[57]

The First and Second Battle of Amman were part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I and the Arab Revolt, taking place in 1918. Amman had a strategic location along the Hejaz Railway; its capture by British forces and the Hashemite Arab army facilitated the British advance towards Damascus.[58] The second battle was won by the British, resulting in the establishment of the British Mandate.

In 1921, the Hashemite emir and later king Abdullah I designated Amman instead of al-Salt to be the capital of the newly created state, the Emirate of Transjordan, which became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1950. Its function as the capital of the country attracted immigrants from different Levantine areas, particularly from al-Salt, a nearby city that had been the largest urban settlement east of the Jordan River at the time. The early settlers who came from Palestine were overwhelmingly from Nablus, from which many of al-Salt's inhabitants had originated. They were joined by other immigrants from Damascus. Amman later attracted people from the southern part of the country, particularly al-Karak and Madaba. The city's population was around 10,000 in the 1930s.[59]

The British report from 1933 shows around 1,700 Circassians living in Amman.[60] Yet the community was far from insulated. Local urban and nomadic communities formed alliances with the Circassians, some of which are still present today. This cemented the status of Circassians in the re-established city.[50]

Jordan gained its independence in 1946 and Amman was designated the country's capital. Amman received many refugees during wartime events in nearby countries, beginning with the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. A second wave arrived after the Six-Day War in 1967. In 1970, Amman was a battlefield during the conflict between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Jordanian Army known as Black September. The Jordanian Army defeated the PLO in 1971, and the latter were expelled to Lebanon.[61] The first wave of Iraqi and Kuwaiti refugees settled in the city after the 1991 Gulf War, with a second wave occurring in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

On 9 November 2005, Al-Qaeda under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's leadership launched coordinated explosions in three hotel lobbies in Amman, resulting in 60 deaths and 115 injured. The bombings, which targeted civilians, caused widespread outrage among Jordanians.[62] Jordan's security as a whole was dramatically improved after the attack, and no major terrorist attacks have been reported since then.[63][64] Most recently a wave of Syrian refugees have arrived in the city during the ongoing Syrian Civil War which began in 2011. Amman was a principal destination for refugees for the security and prosperity it offered.[65]

During the last ten years, the city has experienced an economic, cultural and urban boom. The large growth in population has significantly increased the need for new accommodation, and new districts of the city were established at a quick pace. This strained Jordan's scarce water supply and exposed Amman to the dangers of quick expansion without careful municipal planning. Amman is the site of major mega projects such as the Abdali Urban Regeneration Project and the Jordan Gate Towers. The city contains several high-end hotel franchises including the Four Seasons Hotel Amman, Sheraton Hotel Amman, Fairmont Amman, St. Regis Hotel Amman, Le Royal Hotel and others.

Geography

Amman is situated on the East Bank Plateau, an upland characterized by three major wadis which run through it.[66] Originally, the city had been built on seven hills.[67] Amman's terrain is typified by its mountains.[68] The most important areas in the city are named after the hills or mountains they lie on.[69] The area's elevation ranges from 1,000 to 1,100 m (3,300 to 3,600 ft).[70] Al-Salt and al-Zarqa are located to the northwest and northeast, respectively, Madaba is located to the west, and al-Karak and Ma'an are to Amman's southwest and southeast, respectively. One of the only remaining springs in Amman now supplies the Zarqa River with water.[71]

Trees found in Amman include Aleppo pine, Mediterranean cypress and Phoenician juniper.[72]

Climate

Amman's position on the mountains near the Mediterranean climate zone places it under the semi-arid climate classification (Köppen climate: BSh borders on BSk). Summers are moderately long, mildly hot and breezy; however, one or two heat waves may occur during summer. Spring is brief and warm, where highs reach 28 °C (82 °F). Spring usually starts between April and May, and lasts about a month. Winter usually starts around the end of November and continues from early to mid-March. Temperatures are usually near or below 17 °C (63 °F), with snow occasionally falling once or twice a year. Rain averages about 300 mm (12 in) a year and periodic droughts are common, where most rain falls between November and April.[73] At least 120 days of heavy fog per year is usual.[74] Difference in elevation plays a major role in the different weather conditions experienced in the city: snow may accumulate in the western and northern parts of Amman (an average altitude of 1,000 m (3,300 ft) above sea level) while at the same time it could be raining at the city center (elevation of 700 m (2,300 ft).

Amman has extreme examples of microclimate, and almost every district exhibits its own weather.[75] It is known among locals that some boroughs such as the northern suburb of Abu Nser are among the coldest in the city and can experience frost, while other districts such as Marka experience much warmer temperatures.

The temperatures listed below are taken from the weather station at the center of the city which is at an elevation of 700 meters (2,300 ft) above sea level. At higher elevations, the temperatures are usually lower during winter and higher during summer. For example, in areas such as al-Jubaiha, Sweileh, Khalda, and Abu Nser, Tabarbour, Basman which are at/higher than 700 m (2,300 ft) above sea level have average temperatures of 7 to 9 °C (45 to 48 °F) in the day and 1 to 3 °C (34 to 37 °F) at night in January. In August, the average high temperatures in these areas are 25 to 28 °C (77 to 82 °F) in the day and 14 to 16 °C (57 to 61 °F) at night.

| Climate data for Amman | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

32.6 (90.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

40.6 (105.1) |

43.4 (110.1) |

43.2 (109.8) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

43.4 (110.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

23.7 (74.66) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60.6 (2.39) |

62.8 (2.47) |

34.1 (1.34) |

7.1 (0.28) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

7.1 (0.28) |

23.7 (0.93) |

46.3 (1.82) |

245.0 (9.65) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.0 | 10.9 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 51.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 182.0 | 226.3 | 266.6 | 328.6 | 369.0 | 387.5 | 365.8 | 312.0 | 275.9 | 225.0 | 179.8 | 3,289.7 |

| Source 1: Jordan Meteorological Department[76] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1961–1990),[77] Pogoda.ru.net (records)[78] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7.5 |

Local government

Amman is governed by a 41-member city council elected in four-year term direct elections. All Jordanian citizens above 18 years old are eligible to vote in the municipal elections. However, the mayor is appointed by the king and not through elections.[16] In 1909 a city council was established in Amman by Circassian Ismael Babouk who became the first-ever mayor of the capital, and in 1914 Amman's first city district center was founded.[80]

The Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) has been investing in making the city a better place, through a number of initiatives. Green Amman 2020 was initiated in 2014, aiming to turn the city to a green metropolis by 2020. According to official statistics, only 2.5% of Amman is green space.[81] In 2015 GAM and Zain Jordan started operating free-of-charge Wi-Fi services at 15 locations, including Wakalat Street, Rainbow Street, The Hashemite Plaza, Ashrafieh Cultural Complex, Zaha Cultural Center, Al Hussein Cultural Center, Al Hussein Public Parks and others.[82]

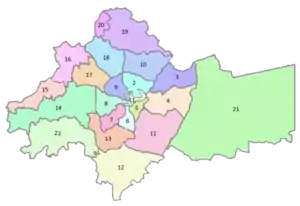

Administrative divisions

Jordan is divided into twelve administrative divisions, each called a governorate. Amman Governorate divides into nine districts, five of which are divided into sub-districts. The Greater Amman Municipality has 22 areas which are further divided into neighborhoods.[83]

The city is administered as the Greater Amman Municipality and covers 22 areas which include:[84][85]

| Number | Area | Area (km2) | Population (2015) | Number | Area | Area (km2) | Population (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al-Madinah | 3.1 | 34,988 | 12 | Kherbet Al-Souk | 0.5 | 186,158 |

| 2 | Basman | 13.4 | 373,981 | 13 | Al-Mgablein | 23 | 99,738 |

| 3 | Marka | 23 | 148,100 | 14 | Wadi Al-Seer | 80 | 241,830 |

| 4 | Al-Nasr | 28.4 | 258,829 | 15 | Badr Al-Jadeedah | 19 | 17,891 |

| 5 | Al-Yarmouk | 5.5 | 180,773 | 16 | Sweileh | 20 | 151,016 |

| 6 | Ras Al-Ein | 6.8 | 138,024 | 17 | Tla' Al-Ali | 19.8 | 251,000 |

| 7 | Bader | 10.1 | 229,308 | 18 | Jubeiha | 25.9 | 197,160 |

| 8 | Zahran | 13.8 | 107,529 | 19 | Shafa Badran | 45 | 72,315 |

| 9 | Al-Abdali | 15 | 165,333 | 20 | Abu Nseir | 50 | 72,489 |

| 10 | Tariq | 25 | 175,194 | 21 | Uhod | 250 | 40,000 |

| 11 | Qweismeh | 45.9 | 296,763 | 22 | Marj Al-Hamam | 53 | 82,788 |

Economy

Banking sector

The banking sector is one of the principal foundations of Jordan's economy. Despite the unrest and economic difficulties in the Arab world resulting from the Arab Spring uprisings, Jordan's banking sector maintained its growth in 2014. The sector consists of 25 banks, 15 of which are listed on the Amman Stock Exchange. Amman is the base city for the international Arab Bank, one of the largest financial institutions in the Middle East, serving clients in more than 600 branches in 30 countries on five continents. Arab Bank represents 28% of the Amman Stock Exchange and is the highest-ranked institution by market capitalization on the exchange.[86]

Tourism

Amman is the 4th most visited Arab city and the ninth highest recipient of international visitor spending. Roughly 1.8 million tourists visited Amman in 2011 and spent over $1.3 billion in the city.[87] The expansion of Queen Alia International Airport is an example of the Greater Amman Municipality's heavy investment in the city's infrastructure. The recent construction of a public transportation system and a national railway, and the expansion of roads, are intended to ease the traffic generated by the millions of annual visitors to the city.[88]

Amman, and Jordan in general, is the Middle East's hub for medical tourism. Jordan receives the most medical tourists in the region and the fifth highest in the world. Amman receives 250,000 foreign patients a year and over $1 billion annually.[89]

Business

Amman is introducing itself as a business hub. The city's skyline is being continuously transformed through the emergence of new projects. A significant portion of business flowed into Amman following the 2003 Iraq War. Jordan's main airport, Queen Alia International Airport, is located south of Amman and is the hub for the country's national carrier Royal Jordanian, a major airline in the region.[90] The airline is headquartered in Zahran district. Rubicon Group Holding and Maktoob, two major regional information technology companies, are based in Amman, along with major international corporations such as Hikma Pharmaceuticals, one of the Middle East's largest pharmaceutical companies, and Aramex, the Middle East's largest logistics and transportation company.[91][92]

In a report by Dunia Frontier Consultants, Amman, along with Doha, Qatar and Dubai, United Arab Emirates, are the favored hubs for multinational corporations operating in the Middle East and North Africa region.[15] In FDI magazine, Amman was chosen as the Middle Eastern city with the most potential to be a leader in foreign direct investment in the region.[91] Furthermore, several of the world's largest investment banks have offices in Amman including Standard Chartered, Société Générale, and Citibank.[93]

Demographics

| Year | Historical population | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 7250 BC | 3,000 | — |

| 1879 | 500 | −83.3% |

| 1906 | 5,000 | +900.0% |

| 1930 | 10,000 | +100.0% |

| 1940 | 20,000 | +100.0% |

| 1952 | 108,000 | +440.0% |

| 1979 | 848,587 | +685.7% |

| 1999 | 1,864,500 | +119.7% |

| 2004 | 2,315,600 | +24.2% |

| 2010 | 2,842,629 | +22.8% |

| 2015 | 4,007,526 | +41.0% |

| Source: [94][95][16] | ||

| Largest groups of Arab foreign residents[96] | |

| Nationality | Population (2015) |

|---|---|

| 435,578 | |

| 390,631 | |

| 308,091 | |

| 121,893 | |

| 27,109 | |

| 21,649 | |

| Other | 147,742 |

The population of Amman reached 4,007,526 in 2015; the city contains about 42% of Jordan's entire population.[8] It has a land area of 1,680 km2 (648.7 sq mi) which yields a population density of about 2,380 inhabitants per square kilometer (6,200/sq mi).[97] The population of Amman has risen exponentially with the successive waves of immigrants and refugees arriving throughout the 20th century. From a population of roughly 1,000 in 1890, Amman grew to around 1,000,000 inhabitants in 1990, primarily as a result of immigration, but also due to the high birthrate in the city.[98] Amman had been abandoned for centuries until hundreds of Circassians settled it in the 19th century. Today, about 40,000 Circassians live in Amman and its vicinity.[99] After Amman became a major hub along the Hejaz Railway in 1914, many Muslim and Christian merchant families from al-Salt immigrated to the city.[100] A large proportion of Amman's inhabitants have Palestinian roots (urban or rural origin), and the two main demographic groups in the city today are Arabs of Palestinian or Jordanian descent. Other ethnic groups comprise about 2% of the population. There are no official statistics about the proportion of people of Palestinian or Jordanian descent.[101]

New arrivals consisting of Jordanians from the north and south of the country and immigrants from Palestine had increased the city's population from 30,000 in 1930 to 60,000 in 1947.[102] About 10,000 Palestinians, mostly from Safed, Haifa and Acre, migrated to the city for economic opportunities before the 1948 war.[103] Many of the immigrants from al-Salt from that time were originally from Nablus.[104] The 1948 war caused an exodus of urban Muslim and Christian Palestinian refugees, mostly from Jaffa, Ramla and Lydda, to Amman,[103] whose population swelled to 110,000.[102] With Jordan's capture of the West Bank during the war, many Palestinians from that area steadily migrated to Amman between 1950 and 1966, before another mass wave of Palestinian refugees from the West Bank moved to the city during the 1967 War. By 1970, the population had swelled to an estimated 550,000.[102] A further 200,000 Palestinians arrived after their expulsion from Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War. Several large Palestinian refugee camps exist around the center of Amman.[105]

Because Amman lacks a deep-rooted native population, the city does not have a distinct Arabic dialect, although recently such a dialect utilizing the various Jordanian and Palestinian dialects, has been forming.[106] The children of immigrants in the city are also increasingly referring to themselves as "Ammani", unlike much of the first-generation inhabitants who identify more with their respective places of origin.[107]

Religion

Amman has a mostly Sunni Muslim population, and the city contains numerous mosques.[108] Among the main mosques is the large King Abdullah I Mosque, built between 1982 and 1989. It is capped by a blue mosaic dome beneath which 3,000 Muslims may offer prayer. The Abu Darweesh Mosque, noted for its checkered black-and-white pattern, has an architectural style that is unique to Jordan.[109] The mosque is situated on Jabal Ashrafieh, the highest point in the city. The mosque's interior is marked by light-colored walls and Persian carpets. During the 2004 Amman Message conference, edicts from various clergy-members afforded the following schools of thought as garnering collective recognition: Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki, Shafi'i, Ja'fari, Zahiri, Zaydi, Ibadi, tassawuf-related Sufism, Muwahhidism and Salafism.[110] Amman also has a small Druze community.[111]

Large numbers of Christians from throughout Jordan, particularly from al-Salt, have moved to Amman. Nearby Fuheis is a predominantly Christian town located to the northwest of the city.[112] A small Armenian Catholic community of around 70 families is present in the city.[113] Ecclesiastical courts for matters of personal status are also located in Amman. A total of 16 historic churches are located in Umm ar-Rasas ruins in Al-Jeezah district; the site is believed to have initially served as Roman fortified military camps which gradually became a town around the 5th century AD. It has not been completely excavated. It was influenced by several civilizations including the Romans, Byzantines and Muslims. The site contains some well-preserved mosaic floors, particularly the mosaic floor of the Church of Saint Stephen.[114]

Cityscape

Downtown Amman, the city center area (known in Arabic as Al-Balad), has been dwarfed by the sprawling urban area that surrounds it. Despite the changes, much remains of its old character. Jabal Amman is a well-known tourist attraction in old Amman, where the city's greatest souks, fine museums, ancient constructions, monuments, and cultural sites are found. Jabal Amman also contains the famous Rainbow Street and the cultural Souk Jara market.

Architecture

Residential buildings are limited to four stories above street level and if possible another four stories below, according to the Greater Amman Municipality regulations. The buildings are covered with thick white or beige limestone or sandstone.[115] The buildings usually have balconies on each floor, with the exception of the ground floor, which has a front and back yard. Some buildings make use of Mangalore tiles on the roofs or on the roof of covered porches. Hotels, towers and commercial buildings are either covered by stone, plastic or glass.[116] There is also many other beautiful architecture in the city.

High-rise construction and towers

Zahran district in west Amman is the location of the Jordan Gate Towers, the first high-rise towers in the city. It is a high-class commercial and residential project under construction, close to the 6th Circle. The towers are one of the best-known skyscrapers in the city.[117] The southern tower will host a Hilton Hotel, while the northern tower will host offices. The towers are separated by a podium that is planned to become a mall. It also contains bars, swimming pools and conference halls. The developers are Bahrain's Gulf Finance House, the Kuwait Investment and Finance Company (KIFC). The project is expected to be opened by 2018.[117]

Abdali Urban Regeneration Project in Abdali district will host a mall, a boulevard along with several hotels, commercial and residential towers. Valued at more than US$5 billion, the Abdali project will create a new visible center for Amman and act as the major business district for the city.[118] The first phase contains about ten towers, five of which are under construction to be completed by 2016.[119] Across 30,000 square meters of land, a central dynamic park is the main feature of phase II which will serve as a focal theme for mainly residential, office, hotel and retail developments over 800,000 square meters.[120]

The towers in the first phase include Rotana Hotel Amman, W Hotel Amman, The Heights Tower, Clemenceau Medical Center tower, Abdali mall tower, Abdali Gateway tower, K tower, Vertex Tower, Capital tower, Saraya headquarters tower and Hamad tower.[121]

Culture

Museums

The largest museum in Jordan is The Jordan Museum. It contains much of the valuable archeological findings in the country,[122] including some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Neolithic limestone statues of 'Ain Ghazal, and a copy of the Mesha Stele. Other museums include the Duke's Diwan, Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Jordan Archaeological Museum, The Children's Museum Jordan, The Martyrs' Memorial and Museum, the Royal Automobile Museum, the Prophet Mohammad Museum, the Museum of Parliamentary Life, the Jordan Folklore Museum, and museums at the University of Jordan.[123]

Lifestyle

Amman is considered one of the most liberal cities in the Arab world.[124] The city has become one of the most popular destinations for expatriates and college students who seek to live, study, or work in the Middle East or the Arab world in general.[125] The city's culinary scene has changed from its shawarma stands and falafel joints to embrace many popular international restaurants and fast-food outlets such as Asian fusion restaurants, French bistros and Italian trattorias. The city has become famous for its fine dining scene among Western expatriates and Persian Gulf tourists.[126]

.JPG.webp)

Large shopping malls were built during the 2000s in Amman, including the Mecca Mall, Abdoun Mall, City Mall, Al-Baraka Mall, Taj Mall, Zara Shopping Center, Avenue Mall, and Abdali Mall in Al Abdali.[127] Wakalat Street ("Agencies Street") is Amman's first pedestrian-only street and carries a lot of name-label clothes. The Sweifieh area is considered to be the main shopping district of Amman.[128]

Nightclubs, music bars and shisha lounges are present across Amman, changing the city's old image as the conservative capital of the kingdom. This burgeoning new nightlife scene is shaped by Jordan's young population.[129] In addition to the wide range of drinking and dancing venues on the social circuit of the city's affluent crowd, Amman hosts cultural entertainment events, including the annual Amman Summer Festival. Souk Jara is a Jordanian weekly flea market event that occurs every Friday throughout the summer.[130] Sweifieh is considered to be the unofficial red-light district of Amman as it holds most of the city's nightclubs, bars.[131] Jabal Amman and Jabal al-Weibdeh are home to many pubs and bars as well, making the area popular among bar hoppers.[126]

Alcohol is widely available in restaurants, bars, nightclubs, and supermarkets.[132][133] There are numerous nightclubs and bars across the city, especially in West Amman. As of 2011, there were 77 registered nightclubs in Jordan (excluding bars and pubs), overwhelmingly located in the capital city.[134] In 2009, there were 222 registered liquor stores in Amman.[135]

Cuisine

Danielle Pergament of The New York Times described Ammani cuisine as a product of several cuisines in the region, writing that it combines "the bright vegetables from Lebanon, crunchy falafels from Syria, juicy kebabs from Egypt and, most recently, spicy meat dishes from Jordan's neighbor, Iraq. It's known as the food of the Levant – an ancient word for the area bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian peninsula. But the food here isn't just the sum of its calories. In this politically, religiously and ethnically fraught corner of the world, it is a symbol of bloodlines and identity."[136] However, the city's street food scene makes the Ammani cuisine distinctive.[2][137]

Sports

Amman-based football clubs Al-Wehdat and Al-Faisaly, both former league champions, share one of the most popular rivalries in the local football scene.[138] Amman hosted the 2016 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup along with Irbid and Zarqa.[139][140]

The 2007 Asian Athletics Championships and more than one edition of the IAAF World Cross Country Championships were held in the city.[141] Amman also hosts the Jordan Rally, which form part of the FIA World Rally Championship, becoming one of the largest sporting events ever held in Jordan.[142]

Amman is home to a growing number of foreign sports such as skateboarding and rugby; the latter has two teams based in the city: Amman Citadel Rugby Club and Nomads Rugby Club.[143] In 2014, German non-profit organization Make Life Skate Life completed construction of the 7Hills Skatepark, a 650 square meter concrete skatepark located at Samir Rifai park in Downtown Amman.[144]

Media and music

The majority of Jordan's radio stations are based in Amman. The first radio station to originate in the city was Hunna Amman in 1959; it mainly broadcast traditional Bedouin music.[145] In 2000, Amman Net became the first de facto private radio station to be established in the country, despite private ownership of radio stations being illegal at the time.[146] After private ownership was legalized in 2002, several more radio stations were created. There were eight registered radio stations broadcasting from Amman by 2007.[147] Most English language stations play pop music targeted towards young audiences.[148]

Most Jordanian newspapers and news stations are situated in Amman. Daily newspapers published in Amman include Alghad,[149] Ad-Dustour,[150] The Jordan Times,[149] and Al Ra'i, the most circulated newspaper in the country.[151] In 2011, Al Ra'i was ranked the 5th most popular newspaper in the Arab world by Forbes Middle-East report.[152] Al-Arab Al-Yawm is the only daily pan-Arab newspaper in Jordan. The two most popular Jordanian TV channels, Ro'ya TV and JRTV, are based in Amman.

Aside from mainstream Arabic pop, there is a growing independent music scene in the city which includes many bands that have sizable audiences across the Arab world. Local Ammani bands along with other bands in the Middle East gather in the Roman Theater during the Al-Balad Music Festival held annually in August. Music genres of the local bands are diverse, ranging from heavy metal to Arabic Rock, jazz and rap. Performers include JadaL, Torabyeh, Bilocate, Akher Zapheer, Autostrad and El Morabba3.[153]

Events

Many events take place in Amman, including Red Bull-sponsored events Soundclash and Soapbox race, the second part of Jerash Festival, Al-Balad Music Festival, Amman Marathon, Made in Jordan Festival, Amman Book Festival and New Think Festival.[154] Venues for such cultural events often include the Roman and Odeon Theaters downtown, the Ras al Ain Hanger, King Hussein Business Park, Rainbow Theater and Shams Theater, the Royal Film Commission, Shoman libraries and Darat al Funun, and the Royal Cultural Center at Sports City. In addition to large-scale events and institutional planning, scholars point to tactical urbanism as a key element of the city's cultural fabric.[155]

Transportation

With the exception of a functioning railway system, Amman has a railway station as part of the Hejaz Railway. Amman has a developed public and private transportation system. There are two international airports in Amman.

Airports

The main airport serving Amman is Queen Alia International Airport, situated about 30 km (18.64 mi) south of Amman. Much smaller is Amman Civil Airport, a one-terminal airport that serves primarily domestic and nearby international routes and the army. Queen Alia International Airport is the major international airport in Jordan and the hub for Royal Jordanian, the flag carrier. Its expansion was recently done and modified, including the decommissioning of the old terminals and the commissioning of new terminals costing $700M, to handle over 16 million passengers annually.[156] It is now considered a state-of-the-art airport and was named 'the best airport in the Middle East' for 2014 and 2015 and 'the best improvement in the Middle East' for 2014 by Airport Service Quality Survey, the world's leading airport passenger satisfaction benchmark program.[157]

Roads

Amman has an extensive road network, although the mountainous terrain of the area has prevented the connection of some main roads, which are instead connected by bridges and tunnels. The Abdoun Bridge spans Wadi Abdoun and connects the 4th Circle to Abdoun Circle. It is considered one of Amman's many landmarks and is the first curved suspended bridge to be built in the country.[158]

.jpg.webp)

There are eight circles, or roundabouts, that span and connect west Amman. Successive waves of refugees to the city has led to the rapid construction of new neighborhoods, but Amman's capacity for new or widened roads remains limited despite the influx. This has resulted in increasing traffic jams, particularly during summer when there are large numbers of tourists and Jordanian expatriates visiting.[159] The municipality began construction on a bus rapid transit (BRT) system as a solution in 2015.[160] In 2015, a ring road encompassing the city was constructed, which aims to connect the northern and southern parts of the city in order for traffic to be diverted outside Amman and to improve the environmental conditions in the city.[161]

Public transportation

The Amman Bus and the Amman Bus Rapid Transit public transportation systems currently serve the city. Construction work on the BRT system started in 2010, but was halted soon after amid feasibility concerns. Resuming in 2015, the first route of the BRT system was inaugurated in 2021, with the second expected to be operational by end of 2022. Another BRT route connecting Amman with Zarqa is also under construction and is expected to be operational by 2023.[162]

The BRT system in Amman runs on 2 routes: the first from Sweileh in northwest Amman to the Ras Al-Ain area next to downtown Amman, and the second from Sweileh to Mahatta terminal in eastern Amman. Both routes meet at the Sports City intersection. The first route is currently served by three lines: 98, 99 and 100.[162]

Ticket price for all lines of Amman Bus and Amman BRT are bought either online via the Amman Bus mobile application or as a rechargeable card in major terminals. Passengers scan their cards or QR codes on phone when boarding the bus, where the price ticket is subtracted from the available balance. The buses are air-conditioned, accessible, monitored with security cameras and have free internet service.[162]

Bus and taxi

The city has frequent bus connections to other cities in Jordan, as well as to major cities in neighboring countries; the latter are also served by service taxis. Internal transport is served by a number of bus routes and taxis. Service taxis, which most often operate on fixed routes, are readily available and inexpensive. The two main bus and taxi stations are Abdali (near the King Abdullah Mosque, the Parliament and Palace of Justice) and the Raghadan Central Bus Station near the Roman theater in the city center. Popular Jordanian bus company services include JETT and Al-Mahatta. Taxis are the most common way to get around in Amman due their high availability and inexpensiveness.[163]

Education

Amman is a major regional center of education. The Amman region hosts Jordan's highest concentration of education centers. There are 20 universities in Amman. The University of Jordan is the largest public university in the city.[164] There are 448 private schools in the city attended by 90,000 students,[165] including Amman Baccalaureate School, Amman Academy, Amman National School, Modern American School (Jordan), American Community School in Amman and National Orthodox School.

Universities include:

- University of Jordan

- Al-Ahliyya Amman University

- Al-Isra University

- Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan

- Amman Arab University

- Applied Science University

- Arab Academy for Banking and Financial Sciences

- Arab Open University

- Columbia University: Amman Branch

- German-Jordanian University: Amman Branch

- Jordan Academy for Maritime Studies

- Jordan Academy of Music

- Jordan Institute of Banking Studies

- Jordan Media Institute

- Middle East University

- University of Petra

- Philadelphia University

- Princess Sumaya University for Technology

- Queen Noor Civil Aviation Technical College

- World Islamic Sciences and Education University

Twin towns – sister cities

Amman is twinned with:[166][167]

Muscat, Oman (1986)

Muscat, Oman (1986) Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (1988)

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (1988) Cairo, Egypt (1988)

Cairo, Egypt (1988) Rabat, Morocco (1988)

Rabat, Morocco (1988) Sanaa, Yemen (1989)

Sanaa, Yemen (1989) Islamabad, Pakistan (1989)

Islamabad, Pakistan (1989) Ankara, Turkey (1992)

Ankara, Turkey (1992) Khartoum, Sudan (1993)

Khartoum, Sudan (1993) Doha, Qatar (1995)

Doha, Qatar (1995) Istanbul, Turkey (1997)

Istanbul, Turkey (1997) Algiers, Algeria (1998)

Algiers, Algeria (1998) Bucharest, Romania (1999)

Bucharest, Romania (1999) Nouakchott, Mauritania (1999)

Nouakchott, Mauritania (1999) Tunis, Tunisia (1999)

Tunis, Tunisia (1999) Sofia, Bulgaria (2000)

Sofia, Bulgaria (2000) Beirut, Lebanon (2000)

Beirut, Lebanon (2000) Pretoria, South Africa (2002)

Pretoria, South Africa (2002) Tegucigalpa, Honduras (2002)

Tegucigalpa, Honduras (2002) Chicago, United States (2004)[168]

Chicago, United States (2004)[168] Calabria, Italy (2005)

Calabria, Italy (2005) Moscow, Russia (2005)

Moscow, Russia (2005) Astana, Kazakhstan (2005)

Astana, Kazakhstan (2005) Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina (2006)[169]

Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina (2006)[169] Central Governorate, Bahrain (2006)

Central Governorate, Bahrain (2006) Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (2006)

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (2006) San Francisco, United States (2010)[170]

San Francisco, United States (2010)[170] Sylhet, Bangladesh

Sylhet, Bangladesh Singapore, Singapore (2014)

Singapore, Singapore (2014) Yerevan, Armenia (2015)[171]

Yerevan, Armenia (2015)[171] Cincinnati, United States (2015)

Cincinnati, United States (2015)

Gallery

Le Royal Hotel

Le Royal Hotel Downtown Amman

Downtown Amman.JPG.webp) Aerial view

Aerial view

See also

- List of tallest buildings in Amman

References

- Trent Holden, Anna Metcalfe (2009). The Cities Book: A Journey Through the Best Cities in the World. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-74179-887-6. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Amman's Street Food". BeAmman.com. BeAmman.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "New Amman mayor pledges 'fair and responsible' governance". jodantimes.com. 21 August 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "New Member: Yousef Al-Shawarbeh – Amman, Jordan". globalparliamentofmayors.org. June 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Lipiński, Edward (2006). On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age: Historical and Topographical Researches. Peeters Publishers. p. 295. ISBN 978-9042917989.

- Parpola, Simo (1970). Neo-Assyrian Toponyms. Kevaeler: Butzon & Bercker. p. 76.

- "Revealed: the 20 cities UAE residents visit most". Arabian Business Publishing Ltd. 1 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Population Estimates for The End of 2021" (PDF). Department of Statistics (DoS). January 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Michael Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Aqel Biltaji appointed as Amman mayor". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 8 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "West Amman furnished apartments cashing in on tour". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 12 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "How a Startup from the Arab World Grabs 1B Views on YouTube". Forbes. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- IANS/WAM (26 November 2010). "Abu Dhab duke City' in MENA region". sify news. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Amman Favored by MNCs as New Regional Hub". Dunia Frontier Consultants, Doha. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- "About GAM => History". Greater Amman Municipality. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "MISDAR". mansaf.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Lime Plaster statues". British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Prehistoric Settlements of the Middle East". bhavika1990. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christin J. (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective: Volume 1 (Twelfth ed.). Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing. pp. 11–2. ISBN 0-495-00479-0.

- Scarre, Chris, ed. (2005). The Human Past. Thames & Hudson. p. 222.

- "The Old Testament Kingdoms of Jordan". kinghussein.gov.jo. kinghussein.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "Temple of Human Sacrifice: Amman Jordan". Randy McCracken. 22 August 2014. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Rujm al-Malfouf". Livius.org. 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Rujom Al Malfouf (Al Malfouf heap of stones / Tower)". Greater Amman Municipality. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "The Hellenistic Period". kinghussein.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Cohen, Getzel M. (3 October 2006). The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. University of California Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-520-93102-2. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. (27 June 2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC – AD 100. OUP, Oxford. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-967072-7. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- de l'Institut français du Proche-Orient (11 June 2014). The Hellenistic Age – (323 – 30 BC). Contemporain publications. Presses de l'Ifpo. pp. 134–141. ISBN 9782351594384. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "The History of a Land". Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Department of Antiquities (DoA). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Tourism". kinghussein.gov.jo. kinghussein.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- "Amman". kinghussein.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Ali Kassay (2011). Myriam Ababsa; Rami Farouk Daher (eds.). The Exclusion of Amman from Jordanian National Identity. Cities, Urban Practices and Nation Building in Jordan. Cahiers de l'Ifpo Nr. 6. Beirut: Presses de l'Ifpo. pp. 256–271. ISBN 9782351591826. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- Ignacio Arce (2003). "Early Islamic lime kilns from the Near East. The cases from Amman Citadel" (PDF). Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History, Madrid, 20th–24th January 2003. Madrid: S. Huerta: 213–224. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Le Strange 1896, p. 391.

- Le Strange 1896, p. 15 and p. 18.

- Le Strange 1896, p. 392.

- Barber, Malcolm (2003) "The career of Philip of Nablus in the kingdom of Jerusalem," in The Experience of Crusading, vol. 2: Defining the Crusader Kingdom, eds. Peter Edbury and Jonathan Phillips, Cambridge University Press

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-107-60473-5. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Denys Pringle (2009). 'Amman (P4). Secular Buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: An Archaeological Gazetteer. Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 9780521102636. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Johns, Jeremy (1994). "The Long Durée: State and Settlement Strategies in Southern Transjordan across the Islamic Centuries". In Rogan, Eugene L.; Tell, Tariq (eds.). Village, Steppe and State: The Social Origins of Modern Jordan. London: British Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 9781850438298. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Le Strange 1896, p. 41.

- Walker 2015, p. 119.

- Walker 2015, pp. 119–120.

- Walker 2015, p. 120.

- Walker 2015, pp. 120–121.

- Walker 2015, p. 121.

- Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. The Contemporary Middle East (Book 5). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9780521817929. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Colin McEvedy (2011). Cities of the Classical World: An Atlas and Gazetteer of 120 Centres of Ancient Civilization. London: Allen Lane/Penguin Books. p. 37. ISBN 9780141967639. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Hamed-Troyansky, Vladimir (2017). "Circassians and the Making of Amman, 1878–1914". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 49 (4): 605–623. doi:10.1017/S0020743817000617. S2CID 165801425.

- Eugene L. Rogan (11 April 2002). Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-521-89223-0. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "The Circassians in Jordan". 20 August 2004. Archived from the original on 20 August 2004.

- Hanania 2018, p. 2.

- Hanania 2018, p. 3.

- PEF Survey of Palestine, Survey of Eastern Palestine (1889), pages 29 and 291

- Hanania 2018, pp. 3–4.

- "Deputy Mayor of Amman Inaugurates "Documenting Amman" Conference". Bawaba. 30 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Spencer C. Tucker; Priscilla Mary Roberts (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Reem Khamis-Dakwar; Karen Froud (2014). Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics XXVI: Papers from the annual symposium on Arabic Linguistics. New York, 2012. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 31. ISBN 978-9027269683. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Report by His Britannic Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Palestine and Trans-Jordan for the year 1933, Colonial No. 94, His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1934, p. 305.

- "Amman". Jordan Wild Tours. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Anthony H. Cordesman (2006). Arab-Israeli Military Forces in an Era of Asymmetric Wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-275-99186-9. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "تـفـجيـرات عمـان.. حدث أليم لم ينل من إرادة الأردنيين". Addustor (in Arabic). Addustor newspaper. 9 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "تفجيرات عمان 2005 دفعت بالأردن ليكون أكثر يقظة في تصديه للإرهاب". JFRA News (in Arabic). JFRA News. 9 November 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Alexandra Francis (21 September 2015). "Jordan's Refugee Crisis". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Ham, Anthony; Greenway, Paul (2003). Jordan. Lonely Planet. p. 19. ISBN 9781740591652. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Donagan, Zechariah (2009). Mountains Before the Temple. Xulon Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-1615795307. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Bou, Jean (2009). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781107276307. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "About Jordan". Cityscape. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "ارتفاعات مناطق عمان الكبرى عن سطح البحر – ارتفاع محافظات المملكة الاردنية عن سطح البحر". Aswaq Amman (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Jordan Basim-Geography, population and climate". Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. FAO. 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Cordova, Carlos E. (2007). Millennial Landscape Change in Jordan: Geoarchaeology and Cultural Ecology. University of Arizona Press. pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-0-8165-2554-6. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Average Weather in October For Amman, Jordan". WeatherSpark. 26 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Real Estate in Amman and Jordan for Apartments and Villas – Rent & Buy". Cityscape.jo. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ""Ever-growing Amman", Jordan: Urban expansion, social polarisation and contemporary urban planning issues" (PDF). Arlt-lectures.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Climate and Agricultural Information – Amman". Jordan Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- "Amman Airport Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Pogoda.ru.net (Weather and Climate-The Climate of Amman)" (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Average UV index Amman, Jordan Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine – weather-atlas.com

- "GAM council". Greater Amman Municipality. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "For a greener Amman". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Amman to have free Wi-Fi service in 15 selected locations". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 25 May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "نظام التقسيمات الادارية رقم(46)لسنة2000 وتعديلاته(1)". Ministry of Interiors Jordan (in Arabic). moi.gov.jo. 2000. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Greater Amman Municipality – GAM Interactive". Ammancity.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Jordan Banking Sector Brief" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- MasterCard Worldwide. "MasterCard Worldwide's Global Destination Cities Index". Slideshare.net. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Maslen, Richard (27 March 2013). "New Terminal Opening Boosts Queen Alia Airport's Capacity". Routesonline. Manchester, United Kingdom: UBM Information Ltd. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Jordan remains medical tourism hub despite regional unrest". The Jordan Times. 18 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- "Royal Jordanian was the first airline in the Middle East to order the 787 Dreamliner" (PDF). Boeing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Erbil Ranked 5th for Foreign Direct Investment". Iraq Business News. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Hussein Hachem (24 May 2011). "Aramex MEA: the Middle East's biggest courier firm – Lead Features – Business Management Middle East | GDS Publishing". Busmanagementme.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- "Courier Companies of the World". PRLog. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- "Amman". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "ABOUT AMMAN JORDAN". downtown.jo. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "٩.٥ ملايين عدد السكان في الأردن". Ammon News. Ammon News. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- "Turning Drains into Sponges and Water Scarcity into Water Abundance" (PDF). Brad Lancaster. permaculturenews.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Dumper and Stanley, p. 34.

- Albala, p. 267.

- Richmond, p. 124.

- Dakwar, pp. 31–32.

- Suleiman, p. 101.

- Plascov, p. 33.

- Dakwar, p. 31.

- Dumper and Stanley, p. 35.

- Owens, p. 260.

- Jones, p. 64.

- Ring, Salkin and LaBoda, p. 65.

- "Amman – a modern city built on the sands of time". Jordan Travel. jordantoursandtravel.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Global Security Watch—Jordan – Page 134, W. Andrew Terrill – 2010

- U.S. Senate: Committee on Foreign Relations (2005). Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, 2004. Government Printing Office. p. 563. ISBN 978-0-16-072552-4. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Miller, Duane Alexander (November 2011). "The Episcopal Church in Jordan: Identity, Liturgy, and Mission". Journal of Anglican Studies. 9 (2): 134–153. doi:10.1017/S1740355309990271. S2CID 144069423. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Kildani, p. 678.

- "Um er-Rasas (Kastrom Mefa'a)". unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Center. 2004. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- "Stone as Wall Paper: The Evolution of Stone as a Sheathing Material in Twentieth-Century Amman". CSBE. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Mohammed Subaihi (22 October 2013). "فوضى التنظيم والأبنية في عمان". Al Ra'i (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Jordan Gate Towers, Amman". systemair.com. systemair AB. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "About the Abdali Project". Abdali PSC. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Project Overview". Abdali PSC. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Jordan's $5 billion Abdali project: Serious investment potential". Al Bawaba. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Abdali – Facts & Figures". abdali.jo. Abdali PSC. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Scrolling through the millennia at the new Jordan Museum in Amman". The National. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Carole French (2012). Jordan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84162-398-6. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Amman". History of Jordan. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Why Jordan? Why Amman?". amideast.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Ferren, Andrew (22 November 2009). "A Newly Stylish Amman Asserts Itself". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Carole French (2012). Jordan. Bradt. p. 108. ISBN 9781841623986. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "اعادة دراسة واقع شارع الوكالات". Islah News (in Arabic). islahnews.net. 3 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Amman bustles with nightlife, shedding old image". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Souk JARA open from 9 pm to 2 am in Ramadan". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 24 June 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Jordan – Politics". country-stats.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Anthony Ham; Paul Greenway (2003). Jordan. Lonely Planet. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-74059-165-2. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Matthew Teller (2002). Jordan. Rough Guides. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-85828-740-9.

- "3% of Nightclub women are Jordanian | Editor's Choice | Ammon News". En.ammonnews.net. 19 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "الاردن يستورد خمور بقيمة مليونين و(997) الف دينار خلال عام 2008" (in Arabic). sarayanews.com. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Pergament, Danielle (13 January 2008). "All the Foods of the Mideast at Its Stable Center". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Capital Cuisine – A Food Tour in Amman, Jordan". BeAmman.com. BeAmman.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Political rivalry overshadows Amman's derby". Goethe-Institut. Goethe-Institut. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Amman municipality revamping stadiums for U-17 Women's World Cup". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 23 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Amman". FIFA. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Destination Amman". International Association of Athletics Federations. 28 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Jordan Rally gets thumbs up from FIA". Jordan Times. 19 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Against all odds, Jordan's rugby greats are set to storm the Dubai Sevens". 4 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Volunteers open Jordan's first skate park", aljazeera.com, Al Jazeera Media Network, 12 February 2015, archived from the original on 1 October 2015, retrieved 30 September 2015

- Massad, Joseph A. (2001). Colonial Effects: The Making of National Identity in Jordan. Columbia University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0231123235. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Zweiri, Mahjoob; Murphy, Emma C. (2012). The New Arab Media: Technology, Image and Perception. Ithaca Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0863724176. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- The Report: Emerging Jordan 2007. Oxford Business Group. 2007. p. 191. ISBN 9781902339740. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- The Report: Jordan 2011. Oxford Business Group. 2011. p. 184. ISBN 9781907065439. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "الرأي الأردنية | أخبار الأردن والشرق الأوسط والعالم|صحيفة يومية تصدر في عمان الأردن" (in Arabic). Alrai.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ":: جريدة الدستور ::" (in Arabic). Addustour.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Kalyango, Yusuf Jr.; Mould, David H. (2014). Global Journalism Practice and New Media Performance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 78. ISBN 978-1137440556. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.