Indonesia

Indonesia,[lower-alpha 1] officially the Republic of Indonesia,[lower-alpha 2] is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guinea. Indonesia is the world's largest archipelagic state and the 14th-largest country by area, at 1,904,569 square kilometres (735,358 square miles). With over 275 million people, Indonesia is the world's fourth-most populous country and the most populous Muslim-majority country. Java, the world's most populous island, is home to more than half of the country's population.

Republic of Indonesia | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

| Motto: Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Old Javanese) National ideology: Pancasila"Unity in Diversity" | |

| Anthem: Indonesia Raya "Great Indonesia" | |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital | Jakarta (current) Nusantara (under construction) 0°57′28″S 116°41′59″E |

| Largest city | Jakarta 6°10′S 106°49′E |

| Official language and national language | Indonesian |

| Regional languages | Over 700 languages[1] |

| Ethnic groups | Over 1,300 ethnic groups[2] |

| Religion (2018)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Indonesian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Joko Widodo |

• Vice President | Ma'ruf Amin |

• House Speaker | Puan Maharani |

• Chief Justice | Muhammad Syarifuddin |

| Legislature | People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) |

| Regional Representative Council (DPD) | |

| House of Representatives (DPR) | |

| Independence from the Netherlands and Japan | |

| 17 August 1945 | |

• Recognition | 27 December 1949 |

| Area | |

• Land | 1,904,569[4] km2 (735,358 sq mi) (14th) |

• Water (%) | 4.85 |

| Population | |

• Q2 2022 estimate | |

• 2020 census | 270,203,917[6] |

• Density | 143/km2 (370.4/sq mi) (90th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | high · 114th |

| Currency | Indonesian rupiah (Rp) (IDR) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 to +9 (various) |

| Date format | DD/MM/YYYY |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +62 |

| ISO 3166 code | ID |

| Internet TLD | .id |

Indonesia is a presidential republic with an elected legislature. It has 37 provinces, of which eight have special status. The country's capital, Jakarta, is the world's second-most populous urban area. Indonesia shares land borders with Papua New Guinea, East Timor, and the eastern part of Malaysia, as well as maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Australia, Palau, and India (Andaman and Nicobar Islands). Despite its large population and densely populated regions, Indonesia has vast areas of wilderness that support one of the world's highest levels of biodiversity.

The Indonesian archipelago has been a valuable region for trade since at least the 7th century when Srivijaya and later Majapahit traded with entities from mainland China and the Indian subcontinent. Local rulers gradually absorbed foreign influences from the early centuries, and Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms flourished. Sunni traders and Sufi scholars brought Islam, while Christianity was spread by Europeans. Although the Portuguese, the French and British also ruled at some point, the Dutch were the foremost colonial power for much of their presence in the archipelago. The concept of "Indonesia" as a nation-state emerged in the early 20th century, culminating later in the proclamation of Indonesian Independence in 1945. However, it was not until 1949 that the Dutch recognised Indonesia's sovereignty following an armed and diplomatic conflict between the two.

Indonesia consists of thousands of distinct native ethnic and hundreds of linguistic groups, with Javanese being the largest. A shared identity has developed with the motto "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" ("Unity in Diversity" literally, "many, yet one"), defined by a national language, cultural diversity, religious pluralism within a Muslim-majority population, and a history of colonialism and rebellion against it. The economy of Indonesia is the world's 17th-largest by nominal GDP and the 7th-largest by PPP. It is a regional power and is considered a middle power in global affairs. The country is a member of several multilateral organisations, including the United Nations, World Trade Organization, G20, and a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, East Asia Summit, D-8 and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

Etymology

The name Indonesia derives from the Greek words Indos (Ἰνδός) and nesos (νῆσος), meaning "Indian islands".[12] The name dates back to the 19th century, far predating the formation of independent Indonesia.[13] In 1850, George Windsor Earl, an English ethnologist, proposed the terms Indunesians—and, his preference, Malayunesians—for the inhabitants of the "Indian Archipelago or Malay Archipelago".[14] In the same publication, one of his students, James Richardson Logan, used Indonesia as a synonym for Indian Archipelago.[15][16] Dutch academics writing in East Indies publications were reluctant to use Indonesia. They preferred Malay Archipelago (Dutch: Maleische Archipel); the Netherlands East Indies (Nederlandsch Oost Indië), popularly Indië; the East (de Oost); and Insulinde.[17]

After 1900, Indonesia became more common in academic circles outside the Netherlands, and native nationalist groups adopted it for political expression.[17] Adolf Bastian of the University of Berlin popularized the name through his book Indonesien oder die Inseln des Malayischen Archipels, 1884–1894. The first native scholar to use the name was Ki Hajar Dewantara when in 1913, he established a press bureau in the Netherlands, Indonesisch Pers-bureau.[13]

History

Early history

Fossilised remains of Homo erectus, popularly known as the "Java Man", suggest the Indonesian archipelago was inhabited two million to 500,000 years ago.[19][20][21] Homo sapiens reached the region around 43,000 BCE.[22] Austronesian peoples, who form the majority of the modern population, migrated to Southeast Asia from what is now Taiwan. They arrived in the archipelago around 2,000 BCE and confined the native Melanesians to the far eastern regions as they spread east.[23] Ideal agricultural conditions and the mastering of wet-field rice cultivation as early as the eighth century BCE[24] allowed villages, towns, and small kingdoms to flourish by the first century CE. The archipelago's strategic sea-lane position fostered inter-island and international trade, including with Indian kingdoms and Chinese dynasties, from several centuries BCE.[25] Trade has since fundamentally shaped Indonesian history.[26][27]

From the seventh century CE, the Srivijaya naval kingdom flourished due to trade and the influences of Hinduism and Buddhism.[28][29] Between the eighth and tenth centuries CE, the agricultural Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram dynasties thrived and declined in inland Java, leaving grand religious monuments such as Sailendra's Borobudur and Mataram's Prambanan. The Hindu Majapahit kingdom was founded in eastern Java in the late 13th century, and under Gajah Mada, its influence stretched over much of present-day Indonesia. This period is often referred to as a "Golden Age" in Indonesian history.[30]

The earliest evidence of Islamized populations in the archipelago dates to the 13th century in northern Sumatra.[31] Other parts of the archipelago gradually adopted Islam, and it was the dominant religion in Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences, which shaped the predominant form of Islam in Indonesia, particularly in Java.[32]

Colonial era

The first Europeans arrived in the archipelago in 1512, when Portuguese traders, led by Francisco Serrão, sought to monopolise the sources of nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in the Maluku Islands.[33] Dutch and British traders followed. In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and became the dominant European power for almost 200 years. The VOC was dissolved in 1799 following bankruptcy, and the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a nationalised colony.[34]

For most of the colonial period, Dutch control over the archipelago was tenuous. Dutch forces were engaged continuously in quelling rebellions both on and off Java. The influence of local leaders such as Prince Diponegoro in central Java, Imam Bonjol in central Sumatra, Pattimura in Maluku, and the bloody 30-year war in Aceh weakened the Dutch and tied up the colonial military forces.[35][36][37] Only in the early 20th century did Dutch dominance extend to what was to become Indonesia's current boundaries.[37][38][39][40]

The Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation during World War II ended Dutch rule[41][42][43] and encouraged the previously suppressed independence movement.[44] Two days after the surrender of Japan in August 1945, Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, influential nationalist leaders, proclaimed Indonesian independence and were appointed president and vice-president, respectively.[45][46][47][45][48]

The Netherlands attempted to re-establish their rule, and a bitter armed and diplomatic struggle ended in December 1949 when the Dutch formally recognised Indonesian independence in the face of international pressure and transferred sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia.[49][47][50] Despite extraordinary political, social, and sectarian divisions, Indonesians, on the whole, found unity in their fight for independence.[51][52]

Post-World War II

As president, Sukarno moved Indonesia from democracy towards authoritarianism and maintained power by balancing the opposing forces of the military, political Islam, and the increasingly powerful Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI).[53] Tensions between the military and the PKI culminated in an attempted coup in 1965. The army, led by Major General Suharto, countered by instigating a violent anti-communist purge that killed between 500,000 and one million people.[54][55][56] The PKI was blamed for the coup and effectively destroyed.[57][58][59] Suharto capitalised on Sukarno's weakened position, and following a drawn-out power play with Sukarno, Suharto was appointed president in March 1968. His "New Order" administration,[60] supported by the United States,[61][62][63] encouraged foreign direct investment,[64][65] which was a crucial factor in the subsequent three decades of substantial economic growth.

Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[66] It brought out popular discontent with the New Order's corruption and suppression of political opposition and ultimately ended Suharto's presidency.[41][67][68][69] In 1999, East Timor seceded from Indonesia, following its 1975 invasion by Indonesia[70] and a 25-year occupation marked by international condemnation of human rights abuses.[71]

Since 1998, democratic processes have been strengthened by enhancing regional autonomy and instituting the country's first direct presidential election in 2004.[72] Political, economic and social instability, corruption, and instances of terrorism remained problems in the 2000s; however, the economy has performed strongly in the last 15 years. Although relations among the diverse population are mostly harmonious, acute sectarian discontent and violence remain problematic in some areas.[73] A political settlement to an armed separatist conflict in Aceh was achieved in 2005 following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami that killed 130,000 Indonesians.[74]

Geography

Indonesia lies between latitudes 11°S and 6°N and longitudes 95°E and 141°E. It is the world's largest Archipelagic state, extending 5,120 kilometres (3,181 mi) from east to west and 1,760 kilometres (1,094 mi) from north to south.[75] The country's Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investments Affairs says Indonesia has 17,504 islands (with 16,056 registered at the UN)[76] scattered over both sides of the equator, around 6,000 of which are inhabited.[77] The largest are Sumatra, Java, Borneo (shared with Brunei and Malaysia), Sulawesi, and New Guinea (shared with Papua New Guinea).[78] Indonesia shares land borders with Malaysia on Borneo and Sebatik, Papua New Guinea on the island of New Guinea, East Timor on the island of Timor, and maritime borders with Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Palau, and Australia.

At 4,884 metres (16,024 ft), Puncak Jaya is Indonesia's highest peak, and Lake Toba in Sumatra is the largest lake, with an area of 1,145 km2 (442 sq mi). Indonesia's largest rivers are in Kalimantan and New Guinea and include Kapuas, Barito, Mamberamo, Sepik and Mahakam. They serve as communication and transport links between the island's river settlements.[79]

Climate

Indonesia lies along the equator, and its climate tends to be relatively even year-round.[80] Indonesia has two seasons—a wet season and a dry season—with no extremes of summer or winter.[81] For most of Indonesia, the dry season falls between May and October, with the wet season between November and April.[81] Indonesia's climate is almost entirely tropical, dominated by the tropical rainforest climate found on every large island of Indonesia. More cooling climate types do exist in mountainous regions that are 1,300 to 1,500 metres (4,300 to 4,900 feet) above sea level. The oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) prevails in highland areas adjacent to rainforest climates, with reasonably uniform precipitation year-round. In highland areas near the tropical monsoon and tropical savanna climates, the subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cwb) is prevalent with a more pronounced dry season.

Some regions, such as Kalimantan and Sumatra, experience only slight differences in rainfall and temperature between the seasons, whereas others, such as Nusa Tenggara, experience far more pronounced differences with droughts in the dry season and floods in the wet. Rainfall varies across regions, with more in western Sumatra, Java, and the interiors of Kalimantan and Papua, and less in areas closer to Australia, such as Nusa Tenggara, which tends to be dry. The almost uniformly warm waters that constitute 81% of Indonesia's area ensure that land temperatures remain relatively constant. Humidity is quite high, at between 70 and 90%. Winds are moderate and generally predictable, with monsoons usually blowing in from the south and east in June through October and from the northwest in November through March. Typhoons and large-scale storms pose little hazard to mariners; significant dangers come from swift currents in channels, such as the Lombok and Sape straits.[83]

Several studies consider Indonesia to be at severe risk from the projected effects of climate change.[84] These include unreduced emissions resulting in an average temperature rise of around 1 °C (2 °F) by mid-century,[85][86] raising the frequency of drought and food shortages (with an impact on precipitation and the patterns of wet and dry seasons, and thus Indonesia's agriculture system[86]) as well as numerous diseases and wildfires.[86] Rising sea levels would also threaten most of Indonesia's population, who live in low-lying coastal areas.[86][87][88] Impoverished communities would likely be affected the most by climate change.[89]

Geology

Tectonically, most of Indonesia's area is highly unstable, making it a site of numerous volcanoes and frequent earthquakes.[90] It lies on the Pacific Ring of Fire, where the Indo-Australian Plate and the Pacific Plate are pushed under the Eurasian plate, where they melt at about 100 kilometres (62 miles) deep. A string of volcanoes runs through Sumatra, Java, Bali and Nusa Tenggara, and then to the Banda Islands of Maluku to northeastern Sulawesi.[91] Of the 400 volcanoes, around 130 are active.[90] Between 1972 and 1991, there were 29 volcanic eruptions, mostly on Java.[92] Volcanic ash has made agricultural conditions unpredictable in some areas.[93] However, it has also resulted in fertile soils, a factor in historically sustaining the high population densities of Java and Bali.[94]

A massive supervolcano erupted at present-day Lake Toba around 70,000 BCE. It is believed to have caused a global volcanic winter and cooling of the climate and subsequently led to a genetic bottleneck in human evolution, though this is still in debate.[95] The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora and the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa were among the largest in recorded history. The former caused 92,000 deaths and created an umbrella of volcanic ash that spread and blanketed parts of the archipelago and made much of the Northern Hemisphere without summer in 1816.[96] The latter produced the loudest sound in recorded history and caused 36,000 deaths due to the eruption itself and the resulting tsunamis, with significant additional effects around the world years after the event.[97] Recent catastrophic disasters due to seismic activity include the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake.

Biodiversity and conservation

Indonesia's size, tropical climate, and archipelagic geography support one of the world's highest levels of biodiversity, and it is among the 17 megadiverse countries identified by Conservation International. Its flora and fauna are a mixture of Asian and Australasian species.[98] The Sunda Shelf islands (Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and Bali) were once linked to mainland Asia and have a wealth of Asian fauna. Large species such as the Sumatran tiger, rhinoceros, orangutan, Asian elephant, and leopard were once abundant as far east as Bali, but numbers and distribution have dwindled drastically. Having been long separated from the continental landmasses, Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, and Maluku have developed their unique flora and fauna.[99][100] Papua was part of the Australian landmass and is home to a unique fauna and flora closely related to that of Australia, including over 600 bird species.[101]

Indonesia is second only to Australia in terms of total endemic species, with 36% of its 1,531 species of bird and 39% of its 515 species of mammal being endemic.[102] Tropical seas surround Indonesia's 80,000 kilometres (50,000 miles) of coastline. The country has a range of sea and coastal ecosystems, including beaches, dunes, estuaries, mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds, coastal mudflats, tidal flats, algal beds, and small island ecosystems.[12] Indonesia is one of the Coral Triangle countries with the world's most enormous diversity of coral reef fish, with more than 1,650 species in eastern Indonesia only.[103]

British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace described a dividing line (Wallace Line) between the distribution of Indonesia's Asian and Australasian species.[104] It runs roughly north–south along the edge of the Sunda Shelf, between Kalimantan and Sulawesi, and along the deep Lombok Strait, between Lombok and Bali. Flora and fauna on the west of the line are generally Asian, while east from Lombok is increasingly Australian until the tipping point at the Weber Line. In his 1869 book, The Malay Archipelago, Wallace described numerous species unique to the area.[105] The region of islands between his line and New Guinea is now termed Wallacea.[104]

Indonesia's large and growing population and rapid industrialisation present serious environmental issues. They are often given a lower priority due to high poverty levels and weak, under-resourced governance.[106] Problems include the destruction of peatlands, large-scale illegal deforestation (causing extensive haze across parts of Southeast Asia), over-exploitation of marine resources, air pollution, garbage management, and reliable water and wastewater services.[106] These issues contribute to Indonesia's low ranking (number 116 out of 180 countries) in the 2020 Environmental Performance Index. The report also indicates that Indonesia's performance is generally below average in both regional and global context.[107]

Indonesia has one of the world's fastest deforestation rates.[108] In 2020, forests covered approximately 49.1% of the country's land area,[109] down from 87% in 1950.[110] Since the 1970s, log production, various plantations and agriculture have been responsible for much of the deforestation in Indonesia.[110] Most recently, it has been driven by the palm oil industry,[111] which has been criticised for its environmental impact and displacement of local communities.[108][112] The situation has made Indonesia the world's largest forest-based emitter of greenhouse gases.[113] It also threatens the survival of indigenous and endemic species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) identified 140 species of mammals as threatened and 15 as critically endangered, including the Bali myna,[114] Sumatran orangutan,[115] and Javan rhinoceros.[116]

Government and politics

Indonesia is a republic with a presidential system. Following the fall of the New Order in 1998, political and governmental structures have undergone sweeping reforms, with four constitutional amendments revamping the executive, legislative and judicial branches.[117] Chief among them is the delegation of power and authority to various regional entities while remaining a unitary state.[118] The President of Indonesia is the head of state and head of government, commander-in-chief of the Indonesian National Armed Forces (Tentara Nasional Indonesia, TNI), and the director of domestic governance, policy-making, and foreign affairs. The president may serve a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms.[119]

The highest representative body at the national level is the People's Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR). Its main functions are supporting and amending the constitution, inaugurating and impeaching the president,[120][121] and formalising broad outlines of state policy. The MPR comprises two houses; the People's Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR), with 575 members, and the Regional Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah, DPD), with 136.[122] The DPR passes legislation and monitors the executive branch. Reforms since 1998 have markedly increased its role in national governance,[117] while the DPD is a new chamber for matters of regional management.[123][121]

Most civil disputes appear before the State Court (Pengadilan Negeri); appeals are heard before the High Court (Pengadilan Tinggi). The Supreme Court of Indonesia (Mahkamah Agung) is the highest level of the judicial branch and hears final cessation appeals and conducts case reviews. Other courts include the Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) which listens to constitutional and political matters, and the Religious Court (Pengadilan Agama), which deals with codified Islamic Personal Law (sharia) cases.[124] Additionally, the Judicial Commission (Komisi Yudisial) monitors the performance of judges.[125]

Parties and elections

13th Vice President of Indonesia

Since 1999, Indonesia has had a multi-party system. In all legislative elections since the fall of the New Order, no political party has won an overall majority of seats. The Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), which secured the most votes in the 2019 elections, is the party of the incumbent president, Joko Widodo.[126] Other notable parties include the Party of the Functional Groups (Golkar), the Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), the Democratic Party, and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS).

The first general election was held in 1955 to elect members of the DPR and the Constitutional Assembly (Konstituante). The most recent elections in 2019 resulted in nine political parties in the DPR, with a parliamentary threshold of 4% of the national vote.[127] At the national level, Indonesians did not elect a president until 2004. Since then, the president is elected for a five-year term, as are the party-aligned members of the DPR and the non-partisan DPD.[122][117] Beginning with the 2015 local elections, elections for governors and mayors have occurred on the same date. In 2014, the Constitutional Court ruled that legislative and presidential elections would be held simultaneously, starting in 2019.[128]

Administrative divisions

Indonesia has several levels of subdivisions. The first level are the provinces, which have a legislature (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah, DPRD) and an elected governor. A total of 37 provinces have been established from the original eight in 1945,[129] with the most recent change being the split of Central Papua, Highland Papua and South Papua from Papua in 2022.[130] The second level are the regencies (kabupaten) and cities (kota), led by regents (bupati) and mayors (walikota) respectively and a legislature (DPRD Kabupaten/Kota). The third level are the districts (kecamatan, distrik in Papua, or kapanewon and kemantren in Yogyakarta), and the fourth are the villages (either desa, kelurahan, kampung, nagari in West Sumatra, or gampong in Aceh).[131]

The village is the lowest level of government administration. It is divided into several community groups (rukun warga, RW), which are further divided into neighbourhood groups (rukun tetangga, RT). In Java, the village (desa) is divided into smaller units called dusun or dukuh (hamlets), which are the same as RW. Following the implementation of regional autonomy measures in 2001, regencies and cities have become chief administrative units responsible for providing most government services. The village administration level is the most influential on a citizen's daily life and handles village or neighbourhood matters through an elected village head (lurah or kepala desa).[132]

Eight provinces—Aceh, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Papua, Central Papua, Highland Papua, South Papua and West Papua—are granted a special autonomous status (otonomi khusus) from the central government. A conservative Islamic territory, Aceh has the right to create some aspects of an independent legal system implementing sharia.[133] Jakarta is the only city with a provincial government due to its position as the capital of Indonesia.[134][135] Yogyakarta is the only pre-colonial monarchy legally recognised within Indonesia, with the positions of governor and vice governor being prioritised for the reigning Sultan of Yogyakarta and Duke of Pakualaman, respectively.[136] The five Papuan provinces are the only ones where the indigenous people have privileges in their local government.[137]

Sumatra

Sumatra

Islands

Belitung

Sumatra

Java

Java

Yogyakarta

Nusa

Tenggara

Tenggara

Kalimantan

Kalimantan

Kalimantan

Kalimantan

Kalimantan

Sulawesi

Maluku

Sulawesi

↓

Sulawesi

Sulawesi

Sulawesi

Papua

Papua

Papua

Papua

Foreign relations

Indonesia maintains 132 diplomatic missions abroad, including 95 embassies.[138] The country adheres to what it calls a "free and active" foreign policy, seeking a role in regional affairs in proportion to its size and location but avoiding involvement in conflicts among other countries.[139]

Indonesia was a significant battleground during the Cold War. Numerous attempts by the United States and the Soviet Union,[140][141] and China to some degree,[142] culminated in the 1965 coup attempt and subsequent upheaval that led to a reorientation of foreign policy.[143] Quiet alignment with the Western world while maintaining a non-aligned stance has characterised Indonesia's foreign policy since then.[144] Today, it maintains close relations with its neighbours and is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the East Asia Summit. In common with most of the Muslim world, Indonesia does not have diplomatic relations with Israel and has actively supported Palestine. However, observers have pointed out that Indonesia has ties with Israel, albeit discreetly.[145]

Indonesia has been a member of the United Nations since 1950[lower-alpha 3] and was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).[147] Indonesia is a signatory to the ASEAN Free Trade Area agreement, the Cairns Group, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and an occasional OPEC member.[148] Indonesia has been a humanitarian and development aid recipient since 1967,[149][150] and recently, the country established its first overseas aid programme in late 2019.[151]

Military

Indonesia's Armed Forces (TNI) include the Army (TNI–AD), Navy (TNI–AL, which includes Marine Corps), and Air Force (TNI–AU). The army has about 400,000 active-duty personnel. Defence spending in the national budget was 0.7% of GDP in 2018,[152] with controversial involvement of military-owned commercial interests and foundations.[153] The Armed Forces were formed during the Indonesian National Revolution when it undertook guerrilla warfare along with informal militia. Since then, territorial lines have formed the basis of all TNI branches' structure, aimed at maintaining domestic stability and deterring foreign threats.[154] The military has possessed a strong political influence since its founding, which peaked during the New Order. Political reforms in 1998 included the removal of the TNI's formal representation from the legislature. Nevertheless, its political influence remains, albeit at a reduced level.[155]

Since independence, the country has struggled to maintain unity against local insurgencies and separatist movements.[156] Some, notably in Aceh and Papua, have led to an armed conflict and subsequent allegations of human rights abuses and brutality from all sides.[157][158][159] The former was resolved peacefully in 2005,[74] while the latter has continued amid a significant, albeit imperfect, implementation of regional autonomy laws and a reported decline in the levels of violence and human rights abuses as of 2006.[160] Other engagements of the army include the conflict against the Netherlands over the Dutch New Guinea, the opposition to the British-sponsored creation of Malaysia ("Konfrontasi"), the mass killings of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), and the invasion of East Timor, which remains Indonesia's most massive military operation.[161][162]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

Indonesia has a mixed economy in which the private sector and government play vital roles.[164] As the only G20 member state in Southeast Asia,[165] the country has the largest economy in the region and is classified as a newly industrialised country. Per a 2022 estimate, it is the world's 17th largest economy by nominal GDP and 7th in terms of GDP at PPP, estimated to be US$1.289 trillion and US$3.995 trillion, respectively. Per capita GDP in PPP is US$14,535, while nominal per capita GDP is US$4,691.[7] Services are the economy's largest sector and account for 43.4% of GDP (2018), followed by industry (39.7%) and agriculture (12.8%).[166] Since 2009, it has employed more people than other sectors, accounting for 47.7% of the total labour force, followed by agriculture (30.2%) and industry (21.9%).[167]

Over time, the structure of the economy has changed considerably.[168] Historically, it has been weighted heavily towards agriculture, reflecting both its stage of economic development and government policies in the 1950s and 1960s to promote agricultural self-sufficiency.[168] A gradual process of industrialisation and urbanisation began in the late 1960s and accelerated in the 1980s as falling oil prices saw the government focus on diversifying away from oil exports and towards manufactured exports.[168] This development continued throughout the 1980s and into the next decade despite the 1990 oil price shock, during which the GDP rose at an average rate of 7.1%. As a result, the official poverty rate fell from 60% to 15%.[169] Trade barriers reduction from the mid-1980s made the economy more globally integrated. The growth ended with the 1997 Asian financial crisis that severely impacted the economy, including a 13.1% real GDP contraction in 1998 and a 78% inflation. The economy reached its low point in mid-1999 with only 0.8% real GDP growth.[170]

Relatively steady inflation[171] and an increase in GDP deflator and the Consumer Price Index[172] have contributed to strong economic growth in recent years. From 2007 to 2019, annual growth accelerated to between 4% and 6% due to improvements in the banking sector and domestic consumption,[173] helping Indonesia weather the 2008–2009 Great Recession,[174] and regain in 2011 the investment grade rating it had lost in 1997.[175] As of 2019, 9.41% of the population lived below the poverty line, and the official open unemployment rate was 5.28%.[176] During the first year of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the economy suffered its first recession since the 1997 crisis but recovered in the following year.[177]

Indonesia has abundant natural resources. Its primary industries are fishing, petroleum, timber, paper products, cotton cloth, tourism, petroleum mining, natural gas, bauxite, coal and tin. Its main agricultural products are rice, coconuts, soybeans, bananas, coffee, tea, palm, rubber, and sugar cane.[178] These commodities make up a large portion of the country's exports, with palm oil and coal briquettes as the leading export commodities. In addition to refined and crude petroleum as the primary imports, telephones, vehicle parts and wheat cover the majority of additional imports. China, the United States, Japan, Singapore, India, Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand are Indonesia's principal export markets and import partners.[179]

Transport

Indonesia's transport system has been shaped over time by the economic resource base of an archipelago and the distribution of its 275 million people highly concentrated on Java.[180] All transport modes play a role in the country's transport system and are generally complementary rather than competitive. In 2016, the transport sector generated about 5.2% of GDP.[181]

The road transport system is predominant, with a total length of 542,310 kilometres (336,980 miles) as of 2018.[182] Jakarta has the most extended bus rapid transit system globally, boasting 251.2 kilometres (156.1 miles) in 13 corridors and ten cross-corridor routes.[183] Rickshaws such as bajaj and becak and share taxis such as Angkot and Metromini are a regular sight in the country.

Most railways are in Java, used for freight and passenger transport, such as local commuter rail services (mainly in Jakarta and Yogyakarta–Solo) complementing the inter-city rail network in several cities. In the late 2010s, Jakarta and Palembang were the first cities in Indonesia to have rapid transit systems, with more planned for other cities in the future.[184] In 2015, the government announced a plan to build a high-speed rail, which would be the first in Southeast Asia.[185]

Indonesia's largest airport, Soekarno–Hatta International Airport, is among the busiest in the Southern Hemisphere, serving 54 million passengers in 2019. Ngurah Rai International Airport and Juanda International Airport are the country's second-and third-busiest airport, respectively. Garuda Indonesia, the country's flag carrier since 1949, is one of the world's leading airlines and a member of the global airline alliance SkyTeam. The Port of Tanjung Priok is the busiest and most advanced Indonesian port,[186] handling more than 50% of Indonesia's trans-shipment cargo traffic.

Energy

In 2017, Indonesia was the world's 9th largest energy producer with 4,200 terawatt-hours (14.2 quadrillion British thermal units) and the 15th largest energy consumer, with 2,100 terawatt-hours (7.1 quadrillion British thermal units).[187] The country has substantial energy resources, including 22 billion barrels (3.5 billion cubic metres) of conventional oil and gas reserves (of which about 4 billion barrels are recoverable), 8 billion barrels of oil-equivalent of coal-based methane (CBM) resources, and 28 billion tonnes of recoverable coal.[188] While reliance on domestic coal and imported oil has increased,[189] Indonesia has seen progress in renewable energy, with hydropower being the most abundant source. Furthermore, the country has the potential for geothermal, solar, wind, biomass and ocean energy.[190] As of 2019, Indonesia's total national installed power generation capacity stands at 69,678.85 MW.[191]

The country's largest dam, Jatiluhur, has several purposes, including hydroelectric power generation, water supply, flood control, irrigation and aquaculture. The earth-fill dam is 105 m (344 ft) high and withholds a reservoir of 3.0 billion m3 (2.4 million acre⋅ft). It helps to supply water to Jakarta and to irrigate 240,000 ha (590,000 acres) of rice fields[192] and has an installed capacity of 186.5 MW which feeds into the Java grid managed by the State Electricity Company (Perusahaan Listrik Negara, PLN).

Science and technology

Government expenditure on research and development is relatively low (0.3% of GDP in 2019),[193] and Indonesia only ranked 87th (out of 132 economies) on the 2021 Global Innovation Index report.[194] Historical examples of scientific and technological developments include the paddy cultivation technique terasering, which is common in Southeast Asia, and the pinisi boats by the Bugis and Makassar people.[195] In the 1980s, Indonesian engineer Tjokorda Raka Sukawati invented a road construction technique named Sosrobahu that later became widely used in several countries.[196] The country is also an active producer of passenger trains and freight wagons with its state-owned company, the Indonesian Railway Industry (INKA), and has exported trains abroad.[197]

Indonesia has a long history of developing military and small commuter aircraft. It is the only country in Southeast Asia to build and produce aircraft. The state-owned Indonesian Aerospace company (PT. Dirgantara Indonesia) has provided components for Boeing and Airbus.[198] The company also collaborated with EADS CASA of Spain to develop the CN-235, which has been used by several countries.[199] Former President B. J. Habibie played a vital role in this achievement.[200] Indonesia has also joined the South Korean programme to manufacture the 4.5-generation fighter jet KAI KF-21 Boramae.[201]

Indonesia has a space programme and space agency, the National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (Lembaga Penerbangan dan Antariksa Nasional, LAPAN). In the 1970s, Indonesia became the first developing country to operate a satellite system called Palapa,[202] a series of communication satellites owned by Indosat. The first satellite, PALAPA A1, was launched on 8 July 1976 from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, United States.[203] As of 2019, Indonesia has launched 18 satellites for various purposes.[204]

Tourism

Tourism contributed around US$19.7 billion to GDP in 2019. In 2018, Indonesia received 15.8 million visitors, a growth of 12.5% from last year, and received an average receipt of US$967.[206][207] China, Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, and Japan are the top five sources of visitors to Indonesia.[208] Since 2011, Wonderful Indonesia has been the country's international marketing campaign slogan to promote tourism.[209]

Nature and culture are prime attractions of Indonesian tourism. The country has a well-preserved natural ecosystem with rainforests stretching over about 57% of Indonesia's land (225 million acres). Forests on Sumatra and Kalimantan are examples of popular destinations, such as the Orangutan wildlife reserve. Moreover, Indonesia has one of the world's longest coastlines, measuring 54,716 kilometres (33,999 mi). The ancient Borobudur and Prambanan temples, as well as Toraja and Bali with their traditional festivities, are some of the popular destinations for cultural tourism.[211]

Indonesia has nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the Komodo National Park and the Sawahlunto Coal Mine; and a further 19 in a tentative list that includes Bunaken National Park and Raja Ampat Islands.[212] Other attractions include specific points in Indonesian history, such as the colonial heritage of the Dutch East Indies in the old towns of Jakarta and Semarang and the royal palaces of Pagaruyung, Ubud, and Yogyakarta.[211]

Demographics

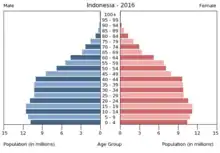

The 2020 census recorded Indonesia's population as 270.2 million, the fourth largest in the world, with a moderately high population growth rate of 1.25%.[213] Java is the world's most populous island,[214] where 56% of the country's population lives.[6] The population density is 141 people per km2 (365 per sq mi),[6] ranking 88th in the world, although Java has a population density of 1,067 people per km2 (2,435 per sq mi). In 1961, the first post-colonial census recorded a total of 97 million people.[215] It is expected to grow to around 295 million by 2030 and 321 million by 2050.[216] The country currently possesses a relatively young population, with a median age of 30.2 years (2017 estimate).[77]

The spread of the population is uneven throughout the archipelago, with a varying habitats and levels of development, ranging from the megacity of Jakarta to uncontacted tribes in Papua.[217] As of 2017, about 54.7% of the population lives in urban areas.[218] Jakarta is the country's primate city and the second-most populous urban area globally, with over 34 million residents.[219] About 8 million Indonesians live overseas; most settled in Malaysia, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, South Africa, Singapore, Hong Kong, the United States, and Australia.[220]

Largest cities in Indonesia 2021 BPS estimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Jakarta  Surabaya |

1 | Jakarta | Jakarta | 10,644,776 | 11 | South Tangerang | Banten | 1,365,688 |  Bekasi .jpg.webp) Medan |

| 2 | Surabaya | East Java | 2,880,284 | 12 | Batam | Riau Islands | 1,230,097 | ||

| 3 | Bekasi | West Java | 2,564,941 | 13 | Bandar Lampung | Lampung | 1,184,949 | ||

| 4 | Medan | North Sumatra | 2,460,858 | 14 | Bogor | West Java | 1,052,359 | ||

| 5 | Bandung | West Java | 2,452,943 | 15 | Pekanbaru | Riau | 994,585 | ||

| 6 | Depok | West Java | 2,085,935 | 16 | Padang | West Sumatra | 913,448 | ||

| 7 | Tangerang | Banten | 1,911,914 | 17 | Malang | East Java | 844,933 | ||

| 8 | Palembang | South Sumatra | 1,686,073 | 18 | Samarinda | East Kalimantan | 831,460 | ||

| 9 | Semarang | Central Java | 1,656,564 | 19 | Denpasar | Bali | 726,599 | ||

| 10 | Makassar | South Sulawesi | 1,427,619 | 20 | Tasikmalaya | West Java | 723,921 | ||

Ethnic groups and languages

Indonesia is an ethnically diverse country, with around 1,300 distinct native ethnic groups.[2] Most Indonesians are descended from Austronesian peoples whose languages had origins in Proto-Austronesian, which possibly originated in what is now Taiwan. Another major grouping is the Melanesians, who inhabit eastern Indonesia (the Maluku Islands, Western New Guinea and the eastern part of the Lesser Sunda Islands).[23][221][222][223]

The Javanese are the largest ethnic group, constituting 40.2% of the population,[2] and are politically dominant.[224] They are predominantly located in the central to eastern parts of Java and also in sizeable numbers in most provinces. The Sundanese are the next largest group (15.4%), followed by Batak, Madurese, Betawi, Minangkabau, Buginese and Malay people.[lower-alpha 4] A sense of Indonesian nationhood exists alongside strong regional identities.[225]

The country's official language is Indonesian, a variant of Malay based on its prestige dialect, which had been the archipelago's lingua franca for centuries. It was promoted by nationalists in the 1920s and achieved official status in 1945 under the name Bahasa Indonesia.[226] Due to centuries-long contact with other languages, it is rich in local and foreign influences.[lower-alpha 5] Nearly every Indonesian speaks the language due to its widespread use in education, academics, communications, business, politics, and mass media. Most Indonesians also speak at least one of more than 700 local languages,[1] often as their first language. Most belong to the Austronesian language family, while over 270 Papuan languages are spoken in eastern Indonesia.[1] Of these, Javanese is the most widely spoken[77] and has co-official status in the Special Region of Yogyakarta.[230]

In 1930, Dutch and other Europeans (Totok), Eurasians, and derivative people like the Indos, numbered 240,000 or 0.4% of the total population.[231] Historically, they constituted only a tiny fraction of the native population and remain so today. Also, the Dutch language never had a substantial number of speakers or official status despite the Dutch presence for almost 350 years.[232] The small minorities that can speak it or Dutch-based creole languages fluently are the aforementioned ethnic groups and descendants of Dutch colonisers. This reflected the Dutch colonial empire's primary purpose, which was commercial exchange as opposed to sovereignty over homogeneous landmasses.[233] Today, there is some degree of fluency by either educated members of the oldest generation or legal professionals,[234] as specific law codes are still only available in Dutch.[235]

Religion

Despite guaranteeing religious freedom in the constitution,[236][121] the government officially recognises only six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism,[237][238] with indigenous religions only partly acknowledged.[238] With 231 million adherents (86.7%) in 2018, Indonesia is the world's most populous Muslim-majority country,[239][240] with Sunnis being the majority (99%).[241] The Shias and Ahmadis, respectively, constitute 1% (1–3 million) and 0.2% (200,000–400,000) of Muslims.[238][242] Almost 11% of Indonesians are Christians, who form the majority in seven provinces in eastern Indonesia.[lower-alpha 6] Most Hindus are Balinese,[244] and most Buddhists are Chinese Indonesians.[245]

The natives of the Indonesian archipelago originally practised indigenous animism and dynamism, beliefs that are common to Austronesian peoples.[246] They worshipped and revered ancestral spirit and believed that supernatural spirits (hyang) might inhabit certain places such as large trees, stones, forests, mountains, or sacred sites.[246] Examples of Indonesian native belief systems include the Sundanese Sunda Wiwitan, Dayak's Kaharingan, and the Javanese Kejawèn. They have significantly impacted how other faiths are practised, evidenced by a large proportion of people—such as the Javanese abangan, Balinese Hindus, and Dayak Christians—practising a less orthodox, syncretic form of their religion.[247]

Hindu influences reached the archipelago as early as the first century CE.[248] The Sundanese Kingdom of Salakanagara in western Java around 130 was the first historically recorded Indianised kingdom in the archipelago.[249] Buddhism arrived around the 6th century,[250] and its history in Indonesia is closely related to that of Hinduism, as some empires based on Buddhism had their roots around the same period. The archipelago has witnessed the rise and fall of powerful and influential Hindu and Buddhist empires such as Majapahit, Sailendra, Srivijaya, and Mataram. Though no longer a majority, Hinduism and Buddhism remain to have a substantial influence on Indonesian culture.[251][252]

Islam was introduced by Sunni traders of the Shafi'i school as well as Sufi traders from the Indian subcontinent and southern Arabia as early as the 8th century CE.[253][254] For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences, resulting in a distinct form of Islam (santri).[32][255] Trade, Islamic missionary activity such as by the Wali Sanga and Chinese explorer Zheng He, and military campaigns by several sultanates helped accelerate the spread of Islam.[256][257] By the end of the 16th century, it had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra.

Catholicism was brought by Portuguese traders and missionaries such as Jesuit Francis Xavier, who visited and baptised several thousand locals.[258][259] Its spread faced difficulty due to the Dutch East India Company policy of banning the religion and the Dutch hostility due to the Eighty Years' War against Catholic Spain's rule. Protestantism is mostly a result of Calvinist and Lutheran missionary efforts during the Dutch colonial era.[260][261][262] Although they are the most common branch, there is a multitude of other denominations elsewhere in the country.[263]

There was a sizeable Jewish presence in the archipelago until 1945, mostly Dutch and some Baghdadi Jews. Since most left after Indonesia proclaimed independence, Judaism was never accorded official status, and only a tiny number of Jews remain today, mostly in Jakarta and Surabaya.[264]

At the national and local level, Indonesia's political leadership and civil society groups have played a crucial role in interfaith relations, both positively and negatively. The invocation of the first principle of Indonesia's philosophical foundation, Pancasila[265][266] (i.e. the belief in the one and only God), often serves as a reminder of religious tolerance,[267] though instances of intolerance have occurred.[73] An overwhelming majority of Indonesians consider religion to be essential and an integral part of life.[268][269]

Education and health

Education is compulsory for 12 years.[270] Parents can choose between state-run, non-sectarian schools or private or semi-private religious (usually Islamic) schools, supervised by the ministries of Education and Religion, respectively.[271] Private international schools that do not follow the national curriculum are also available. The enrolment rate is 93% for primary education, 79% for secondary education, and 36% for tertiary education (2018).[272] The literacy rate is 96% (2018), and the government spends about 3.6% of GDP (2015) on education.[272] In 2018, there were 4,670 higher educational institutions in Indonesia, with most (74%) located in Sumatra and Java.[273][274] According to the QS World University Rankings, Indonesia's top universities are the University of Indonesia, Gadjah Mada University and the Bandung Institute of Technology.[275]

Government expenditure on healthcare was about 3.3% of GDP in 2016.[276] As part of an attempt to achieve universal health care, the government launched the National Health Insurance (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, JKN) in 2014.[277] It includes coverage for a range of services from the public and also private firms that have opted to join the scheme. Despite remarkable improvements in recent decades, such as rising life expectancy (from 62.3 years in 1990 to 71.7 years in 2019)[278] and declining child mortality (from 84 deaths per 1,000 births in 1990 to 23.9 deaths in 2019),[279] challenges remain, including maternal and child health, low air quality, malnutrition, high rate of smoking, and infectious diseases.[280]

Issues

In the economic sphere, there is a gap in wealth, unemployment rate, and health between densely populated islands and economic centres (such as Sumatra and Java) and sparsely populated, disadvantaged areas (such as Maluku and Papua).[281][282] This is created by a situation in which nearly 80% of Indonesia's population lives in the western parts of the archipelago[283] and yet grows slower than the rest of the country.

In the social arena, numerous cases of racism and discrimination, especially against Chinese Indonesians and Papuans, have been well documented throughout Indonesia's history.[284][285] Such cases have sometimes led to violent conflicts, most notably the May 1998 riots and the Papua conflict, which has continued since 1962. LGBT people also regularly face challenges. Although LGBT issues have been relatively obscure, the 2010s (especially after 2016) has seen a rapid surge of anti-LGBT rhetoric, putting LGBT Indonesians into a frequent subject of intimidation, discrimination, and even violence.[286][287] In addition, Indonesia has been reported to have sizeable numbers of child and forced labourers, with the former being prevalent in the palm oil and tobacco industries, while the latter in the fishing industry.[288][289]

Culture

The cultural history of the Indonesian archipelago spans more than two millennia. Influences from the Indian subcontinent, mainland China, the Middle East, Europe,[290][291] Melanesian and Austronesian peoples have historically shaped the cultural, linguistic and religious makeup of the archipelago. As a result, modern-day Indonesia has a multicultural, multilingual and multi-ethnic society,[1][2] with a complex cultural mixture that differs significantly from the original indigenous cultures. Indonesia currently holds twelve items of UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage, including a wayang puppet theatre, kris, batik,[292] pencak silat, angklung, gamelan, and the three genres of traditional Balinese dance.[293]

Art and architecture

Indonesian arts include both age-old art forms developed through centuries and recently developed contemporary art. Despite often displaying local ingenuity, Indonesian arts have absorbed foreign influences—most notably from India, the Arab world, China and Europe, due to contacts and interactions facilitated, and often motivated by trade.[294] Painting is an established and developed art in Bali, where its people are famed for their artistry. Their painting tradition started as classical Kamasan or Wayang style visual narrative, derived from visual art discovered on candi bas reliefs in eastern Java.[295]

There have been numerous discoveries of megalithic sculptures in Indonesia.[296] Subsequently, tribal art has flourished within the culture of Nias, Batak, Asmat, Dayak and Toraja.[297][298] Wood and stone are common materials used as the media for sculpting among these tribes. Between the 8th and 15th centuries, the Javanese civilisation developed refined stone sculpting art and architecture influenced by the Hindu-Buddhist Dharmic civilisation. The temples of Borobudur and Prambanan are among the most famous examples of the practice.[299]

As with the arts, Indonesian architecture has absorbed foreign influences that have brought cultural changes and profound effects on building styles and techniques. The most dominant has traditionally been Indian; however, Chinese, Arab, and European influences have also been significant. Traditional carpentry, masonry, stone and woodwork techniques and decorations have thrived in vernacular architecture, with numbers of traditional houses' (rumah adat) styles that have been developed. The traditional houses and settlements vary by ethnic group, and each has a specific custom and history.[300] Examples include Toraja's Tongkonan, Minangkabau's Rumah Gadang and Rangkiang, Javanese style Pendopo pavilion with Joglo style roof, Dayak's longhouses, various Malay houses, Balinese houses and temples, and also different forms of rice barns (lumbung).

Music, dance and clothing

The music of Indonesia predates historical records. Various indigenous tribes incorporate chants and songs accompanied by musical instruments in their rituals. Angklung, kacapi suling, gong, gamelan, talempong, kulintang, and sasando are examples of traditional Indonesian instruments. The diverse world of Indonesian music genres results from the musical creativity of its people and subsequent cultural encounters with foreign influences. These include gambus and qasida from the Middle East,[301] keroncong from Portugal,[302] and dangdut—one of Indonesia's most popular music genres—with notable Hindi influence as well as Malay orchestras.[303] Today, the Indonesian music industry enjoys both nationwide and regional popularity in Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei,[304][305] due to the common culture and mutual intelligibility between Indonesian and Malay.[306]

Indonesian dances have a diverse history, with more than 3,000 original dances. Scholars believe that they had their beginning in rituals and religious worship.[307] Examples include war dances, a dance of witch doctors, and a dance to call for rain or any agricultural rituals such as Hudoq. Indonesian dances derive their influences from the archipelago's prehistoric and tribal, Hindu-Buddhist, and Islamic periods. Recently, modern dances and urban teen dances have gained popularity due to the influence of Western culture and those of Japan and South Korea to some extent. However, various traditional dances, including those of Java, Bali and Dayak, remain a living and dynamic tradition.[308]

Indonesia has various clothing styles due to its long and rich cultural history. The national costume originates from the country's indigenous culture and traditional textile traditions. The Javanese Batik and Kebaya[309] are arguably Indonesia's most recognised national costumes, though they have Sundanese and Balinese origins as well.[310] Each province has a representation of traditional attire and dress,[290] such as Ulos of Batak from North Sumatra; Songket of Malay and Minangkabau from Sumatra; and Ikat of Sasak from Lombok. People wear national and regional costumes during traditional weddings, formal ceremonies, music performances, government and official occasions,[310] and they vary from traditional to modern attire.

Theatre and cinema

Wayang, the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese shadow puppet theatre display several mythological legends such as Ramayana and Mahabharata.[311] Other forms of local drama include the Javanese Ludruk and Ketoprak, the Sundanese Sandiwara, Betawi Lenong,[312][313] and various Balinese dance dramas. They incorporate humour and jest and often involve audiences in their performances.[314] Some theatre traditions also include music, dancing and silat martial art, such as Randai from the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra. It is usually performed for traditional ceremonies and festivals[315][316] and based on semi-historical Minangkabau legends and love story.[316] Modern performing art also developed in Indonesia with its distinct style of drama. Notable theatre, dance, and drama troupe such as Teater Koma are famous as it often portrays social and political satire of Indonesian society.[317]

The first film produced in the archipelago was Loetoeng Kasaroeng,[318] a silent film by Dutch director L. Heuveldorp. The film industry expanded after independence, with six films made in 1949 rising to 58 in 1955. Usmar Ismail, who made significant imprints in the 1950s and 1960s, is generally considered the pioneer of Indonesian films.[319] The latter part of the Sukarno era saw the use of cinema for nationalistic, anti-Western purposes, and foreign films were subsequently banned, while the New Order utilised a censorship code that aimed to maintain social order.[320] Production of films peaked during the 1980s, although it declined significantly in the next decade.[318] Notable films in this period include Pengabdi Setan (1980), Nagabonar (1987), Tjoet Nja' Dhien (1988), Catatan Si Boy (1989), and Warkop's comedy films.

Independent filmmaking was a rebirth of the film industry since 1998, when films started addressing previously banned topics, such as religion, race, and love.[320] Between 2000 and 2005, the number of films released each year steadily increased.[321] Riri Riza and Mira Lesmana were among the new generation of filmmakers who co-directed Kuldesak (1999), Petualangan Sherina (2000), Ada Apa dengan Cinta? (2002), and Laskar Pelangi (2008). In 2016, Warkop DKI Reborn: Jangkrik Boss Part 1 smashed box office records, becoming the most-watched Indonesian film with 6.8 million tickets sold.[322] Indonesia has held annual film festivals and awards, including the Indonesian Film Festival (Festival Film Indonesia) held intermittently since 1955. It hands out the Citra Award, the film industry's most prestigious award. From 1973 to 1992, the festival was held annually and then discontinued until its revival in 2004.

Mass media and literature

Media freedom increased considerably after the fall of the New Order, during which the Ministry of Information monitored and controlled domestic media and restricted foreign media.[323] The television market includes several national commercial networks and provincial networks that compete with public TVRI, which held a monopoly on TV broadcasting from 1962 to 1989. By the early 21st century, the improved communications system had brought television signals to every village, and people can choose from up to 11 channels.[324] Private radio stations carry news bulletins while foreign broadcasters supply programmes. The number of printed publications has increased significantly since 1998.[324]

Like other developing countries, Indonesia began developing Internet in the early 1990s. Its first commercial Internet service provider, PT. Indo Internet began operation in Jakarta in 1994.[325] The country had 171 million Internet users in 2018, with a penetration rate that keeps increasing annually.[326] Most are between the ages of 15 and 19 and depend primarily on mobile phones for access, outnumbering laptops and computers.[327]

The oldest evidence of writing in the Indonesian archipelago is a series of Sanskrit inscriptions dated to the 5th century. Many of Indonesia's peoples have firmly rooted oral traditions, which help define and preserve their cultural identities.[329] In written poetry and prose, several traditional forms dominate, mainly syair, pantun, gurindam, hikayat and babad. Examples of these forms include Syair Abdul Muluk, Hikayat Hang Tuah, Sulalatus Salatin, and Babad Tanah Jawi.[330]

Early modern Indonesian literature originates in the Sumatran tradition.[331][332] Literature and poetry flourished during the decades leading up to and after independence. Balai Pustaka, the government bureau for popular literature, was instituted in 1917 to promote the development of indigenous literature. Many scholars consider the 1950s and 1960s to be the Golden Age of Indonesian Literature.[333] The style and characteristics of modern Indonesian literature vary according to the dynamics of the country's political and social landscape,[333] most notably the war of independence in the second half of the 1940s and the anti-communist mass killings in the mid-1960s.[334] Notable literary figures of the modern era include Multatuli, Chairil Anwar, Mohammad Yamin, Merari Siregar, Marah Roesli, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, and Ayu Utami.

Cuisine

Indonesian cuisine is one of the world's most diverse, vibrant, and colourful, full of intense flavour.[335] Many regional cuisines exist, often based upon indigenous culture and foreign influences such as Chinese, European, Middle Eastern, and Indian precedents.[336] Rice is the leading staple food and is served with side dishes of meat and vegetables. Spices (notably chilli), coconut milk, fish and chicken are fundamental ingredients.[337]

Some popular dishes such as nasi goreng, gado-gado, sate, and soto are ubiquitous and considered national dishes. The Ministry of Tourism, however, chose tumpeng as the official national dish in 2014, describing it as binding the diversity of various culinary traditions.[338] Other popular dishes include rendang, one of the many Padang cuisines along with dendeng and gulai. Another fermented food is oncom, similar in some ways to tempeh but uses a variety of bases (not only soy), created by different fungi, and is prevalent in West Java.[339]

Sports

Badminton and football are the most popular sports in Indonesia. Indonesia is among the few countries that have won the Thomas and Uber Cup, the world team championship of men's and women's badminton. Along with weightlifting, it is the sport that contributes the most to Indonesia's Olympic medal tally. Liga 1 is the country's premier football club league. On the international stage, Indonesia was the first Asian team to participate in the FIFA World Cup in 1938 as the Dutch East Indies.[340] On a regional level, Indonesia won a bronze medal at the 1958 Asian Games as well as two gold medals at the 1987 and 1991 Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games). Indonesia's first appearance at the AFC Asian Cup was in 1996 and successfully qualified for a total of five tournaments, although they never make the knockout phase.[341]

Other popular sports include boxing and basketball, which has a long history in Indonesia and was part of the first National Games (Pekan Olahraga Nasional, PON) in 1948.[342] Sepak takraw and karapan sapi (bull racing) in Madura are some examples of Indonesia's traditional sports. In areas with a history of tribal warfare, mock fighting contests are held, such as caci in Flores and pasola in Sumba. Pencak Silat is an Indonesian martial art and, in 1987, became one of the sporting events in the SEA Games, with Indonesia appearing as one of the leading competitors. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia is one of the top sports powerhouses by topping the SEA Games medal table ten times since 1977,[343] most recently in 2011.[344]

See also

- List of Indonesia-related topics

- Index of Indonesia-related articles

- Outline of Indonesia

Notes

- UK: /ˌɪndəˈniːziə, -ʒə/ IN-də-NEE-zee-ə, -zhə US: /ˌɪndəˈniːʒə, -ʃə/ (

listen) IN-də-NEE-zhə, -shə[10][11]

listen) IN-də-NEE-zhə, -shə[10][11] - Republik Indonesia ([reˈpublik ɪndoˈnesia] (

listen)) is the most-used official name, though the name Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia, NKRI) also appears in some official documents.

listen)) is the most-used official name, though the name Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia, NKRI) also appears in some official documents. - During the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, Indonesia withdrew from the UN due to the latter's election to the United Nations Security Council, although it returned 18 months later. It marked the first time in UN history that a member state had attempted a withdrawal.[146]

- Small but significant populations of ethnic Chinese, Indians, Europeans and Arabs are concentrated mostly in urban areas.

- These influences include Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, Makassarese, Hindustani, Sanskrit, Tamil, Chinese, Arabic, Dutch, Portuguese and English.[227][228][229]

- East Nusa Tenggara, North Sulawesi, Papua, Central Papua, Highland Papua, South Papua, and West Papua.[243]

References

Citations

- Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twenty-first edition". SIL International. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Na'im, Akhsan; Syaputra, Hendry (2010). "Nationality, Ethnicity, Religion, and Languages of Indonesians" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Statistik Umat Menurut Agama di Indonesia" (in Indonesian). Ministry of Religious Affairs. 15 May 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "UN Statistics" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- "Mid Year Population (Thousand People)". Badan Pusat Statistik - Indonesia. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- "Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2020" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia. 21 January 2021. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Indonesia". World Bank. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "INDONESIA | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- "Indonesia". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- Tomascik, Tomas; Mah, Anmarie Janice; Nontji, Anugerah; Moosa, Mohammad Kasim (1996). The Ecology of the Indonesian Seas – Part One. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. ISBN 978-962-593-078-7.

- Anshory, Irfan (16 August 2004). "The origin of Indonesia's name" (in Indonesian). Pikiran Rakyat. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- Earl 1850, p. 119.

- Logan, James Richardson (1850). "The Ethnology of the Indian Archipelago: Embracing Enquiries into the Continental Relations of the Indo-Pacific Islanders". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia. 4: 252–347.

- Earl 1850, pp. 254, 277–278.

- van der Kroef, Justus M (1951). "The Term Indonesia: Its Origin and Usage". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 71 (3): 166–171. doi:10.2307/595186. JSTOR 595186.

- Brown, Colin (2003). A short history of Indonesia: the unlikely nation?. Allen & Unwin. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-86508-838-9.

- Pope, G.G. (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17: 43–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000355. cited in Whitten, T.; Soeriaatmadja, R.E.; Suraya, A.A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. pp. 309–412.

- Pope, G.G. (1983). "Evidence on the age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (16): 4988–4992. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.4988P. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.16.4988. PMC 384173. PMID 6410399.

- de Vos, J.P.; Sondaar, P.Y. (1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia". Science. 266 (16): 4988–4992. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1726D. doi:10.1126/science.7992059.

- Gugliotta, Guy (July 2008). "The Great Human Migration". Smithsonian Maganize. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 5–7.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 8–9.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 15–18.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 3, 9–11, 13–15, 18–20, 22–23.

- Vickers 2005, pp. 18–20, 60, 133–134.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 22–26.

- Ricklefs 1991, p. 3.

- Lewis, Peter (1982). "The next great empire". Futures. 14 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(82)90071-4.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 3–14.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 12–14.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 22–24.

- Ricklefs 1991, p. 24.

- Schwarz 1994, pp. 3–4.

- Ricklefs 1991, p. 142.

- Friend 2003, p. 21.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 61–147.

- Taylor 2003, pp. 209–278.

- Vickers 2005, pp. 10–14.

- Ricklefs 1991, p. .

- Gert Oostindie; Bert Paasman (1998). "Dutch Attitudes towards Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures, and Slaves" (PDF). Eighteenth-Century Studies. 31 (3): 349–355. doi:10.1353/ecs.1998.0021. hdl:20.500.11755/c467167b-2084-413c-a3c7-f390f9b3a092. S2CID 161921454.

- "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle for Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45". Library of Congress. November 1992. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Robert Elson, The idea of Indonesia: A history (2008) pp 1–12

- Taylor 2003, p. 325.

- H. J. Van Mook (1949). "Indonesia". Royal Institute of International Affairs. 25 (3): 274–285. doi:10.2307/3016666. JSTOR 3016666.

- Charles Bidien (5 December 1945). "Independence the Issue". Far Eastern Survey. 14 (24): 345–348. doi:10.2307/3023219. JSTOR 3023219.

- Reid 1973, p. 30.

- Friend 2003, p. 35.

- "Indonesian War of Independence". Military. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- Friend 2003, pp. 21, 23.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 211–213.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 237–280.

- Melvin 2018, p. 1.

- Robinson 2018, p. 3.

- Robert Cribb (2002). "Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966". Asian Survey. 42 (4): 550–563. doi:10.1525/as.2002.42.4.550. S2CID 145646994.; "Indonesia massacres: Declassified US files shed new light". BBC. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Friend 2003, pp. 107–109.

- Chris Hilton (writer and director) (2001). Shadowplay (Television documentary). Vagabond Films and Hilton Cordell Productions.

- Ricklefs 1991, pp. 280–283, 284, 287–290.

- John D. Legge (1968). "General Suharto's New Order". Royal Institute of International Affairs. 44 (1): 40–47. doi:10.2307/2613527. JSTOR 2613527.

- Melvin 2018, pp. 9–10.

- Vickers 2005, p. 163.

- David Slater, Geopolitics and the Post-Colonial: Rethinking North–South Relations, London: Blackwell, p. 70

- Farid, Hilmar (2005). "Indonesia's original sin: mass killings and capitalist expansion, 1965–66". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 6 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1080/1462394042000326879. S2CID 145130614.

- Robinson 2018, p. 206.

- Delhaise, Philippe F. (1998). Asia in Crisis: The Implosion of the Banking and Finance Systems. Willey. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-471-83450-2.

- Vickers 2005, p. .

- Schwarz 1994, p. .

- Jonathan Pincus; Rizal Ramli (1998). "Indonesia: from showcase to basket case". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 22 (6): 723–734. doi:10.1093/cje/22.6.723.

- Burr, W. (6 December 2001). "East Timor Revisited, Ford, Kissinger, and the Indonesian Invasion, 1975–76". National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 62. Washington, DC: National Security Archive, The George Washington University. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- "Situation of human rights in East Timor". Relief Web. 10 December 1999. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "The Carter Center 2004 Indonesia Election Report" (PDF). The Carter Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- Harsono, Andreas (May 2019). Race, Islam and Power: Ethnic and Religious Violence in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Monash University Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925835-09-0.

- "Indonesia signs Aceh peace deal". The Guardian. 15 August 2005. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Kuoni 1999, p. 88.

- "16,000 Indonesian islands registered at UN". The Jakarta Post. 21 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "The World Factbook: Indonesia". Central Intelligence Agency. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Facts & Figures". Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia, Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Republic of Indonesia". Microsoft Encarta. 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Climate: Observations, projections and impacts" (PDF). Met Office Hadley Centre. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Indonesia and Climate Change: Current Status and Policies" (PDF). World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (30 October 2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- "Climate". U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Overland, Indra et al. (2017) Impact of Climate Change on ASEAN International Affairs: Risk and Opportunity Multiplier, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of International and Strategic Studies (MISIS).

- "Climate Impact Map". Climate Impact Lab. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Case M, Ardiansyah F, Spector E (14 November 2007). "Climate Change in Indonesia: Implications for Humans and Nature" (PDF). WWF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Report: Flooded Future: Global vulnerability to sea level rise worse than previously understood". Climate Central. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Lin, Mayuri Mei; Hidayat, Rafki (13 August 2018). "Jakarta, the fastest-sinking city in the world". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Indonesia: Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile" (PDF). World Bank. April 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Indonesia: Volcano nation". BBC. 5 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Witton 2003, p. 38.

- World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, Volume 10. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. p. 1306. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3.

- Sylviane L. G. Lebon (January 2009). "Volcanic activity and environment: Impacts on agriculture and use of geological data to improve recovery processes" (PDF). University of Iceland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Whitten, T.; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. pp. 95–97.

- Bressan, David (11 August 2017). "Early Humans May Have Lived Through A Supervolcano Eruption". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Tambora". Volcano Discovery. 29 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Bressan, David (31 August 2016). "The Eruption of Krakatoa Was the First Global Catastrophe". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Mumtazah, Hani (22 May 2003). "Indonesia's Natural Wealth: The Right of a Nation and Her People". Islam Online. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- Whitten, T.; Henderson, G.; Mustafa, M. (1996). The Ecology of Sulawesi. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-962-593-075-6.

- Monk, K.A.; Fretes, Y.; Reksodiharjo-Lilley, G. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-962-593-076-3.

- "Indonesia". InterKnowledge Corp. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2006.