Dementia

Dementia is a disorder which manifests as a set of related symptoms, which usually surfaces when the brain is damaged by injury or disease.[2] The symptoms involve progressive impairments in memory, thinking, and behavior, which negatively affects a person's ability to function and carry out everyday activities. Aside from memory impairment and a disruption in thought patterns, the most common symptoms include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. The symptoms may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages.[10][lower-alpha 1] Consciousness is not affected. Dementia ultimately has a significant effect on the individual, caregivers, and on social relationships in general.[2] A diagnosis of dementia requires the observation of a change from a person's usual mental functioning, and a greater cognitive decline than what is caused by normal aging.[12] Several diseases and injuries to the brain, such as a stroke, can give rise to dementia. However, the most common cause is Alzheimer's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder.

| Dementia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Senility,[1] senile dementia |

| |

| Lithography of a man diagnosed with dementia in the 1800s | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to think and remember, emotional problems, problems with language, decreased motivation[2] |

| Complications | poor nutrition, pneumonia, inability to perform self-care tasks, personal safety challenges, Death.[3] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[2] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Alzheimer's disease, vascular disease, Lewy body disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Cognitive testing (Mini–Mental State Examination)[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Delirium, Hypothyroidism[5][6] |

| Prevention | Early education, prevent high blood pressure, prevent obesity, no smoking, social engagement[7] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[2] |

| Medication | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (small benefit)[8] |

| Frequency | 55 million (2021)[2] |

| Deaths | 2.4 million (2016)[9] |

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), has re-described dementia as a major neurocognitive disorder with varying degrees of severity and many causative subtypes. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) also classes dementia as a neurocognitive disorder with many forms or subclasses.[13] Dementia is listed as an acquired brain syndrome, marked by a decline in cognitive function, and is contrasted with neurodevelopmental disorders. Causative subtypes of dementia may be based on a known disorder, such as Parkinson's disease, for Parkinson's disease dementia; Huntington's disease, for Huntington's disease dementia; vascular disease, for vascular dementia – as vascular brain injury, including stroke, often results in vascular dementia; or many other medical conditions, including HIV infection, causing HIV dementia; and prion diseases. Subtypes may be based on various symptoms, possibly due to a neurodegenerative disorder: frontotemporal lobar degeneration for frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body disease for dementia with Lewy bodies. More than one type of dementia, known as mixed dementia, may exist together.

Diagnosis is usually based on history of the illness and cognitive testing with imaging. Blood tests may be taken to rule out other possible causes that may be reversible, such as an underactive thyroid, and to determine the subtype. One commonly used cognitive test is the Mini–Mental State Examination. The greatest risk factor for developing dementia is aging, however dementia is not a normal part of aging. Several risk factors for dementia, such as smoking and obesity, are preventable by lifestyle changes. Screening the general older population for the disorder is not seen to affect the outcome.[14]

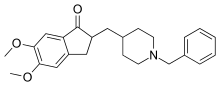

Dementia is currently the seventh leading cause of death worldwide, with 10 million cases reported every year. That is about one new case every 7 seconds a day.[2] There is no known cure for dementia. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil are often used and may be beneficial in mild to moderate disorder. The overall benefit, however, may be minor. There are many measures that can improve the quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers. Cognitive and behavioral interventions may be appropriate for treating associated symptoms of depression.[15]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of dementia are termed as the neuropsychiatric symptoms, also known as the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.[16][17] Behavioral symptoms can include agitation, restlessness, inappropriate behavior, sexual disinhibition, and aggression, which can be verbal or physical.[18] These symptoms may result from impairments in cognitive inhibition.[19] Psychological symptoms can include depression, psychotic hallucinations and delusions, apathy, and anxiety.[18][20] The most commonly affected areas include memory, visuospatial function affecting perception and orientation, language, attention and problem solving. The rate at which symptoms progress occurs on a continuum over several stages, and they vary across the dementia subtypes.[21][10] Most types of dementia are slowly progressive with some deterioration of the brain well established before signs of the disorder become apparent. Often there are other conditions present such as high blood pressure, or diabetes, and there can sometimes be as many as four of these comorbidities.[22]

People with dementia are also more likely to have problems with incontinence: they are three times more likely to have urinary and four times more likely to have fecal incontinence compared to people of similar ages.[23][24]

Dementia symptoms can vary widely from person to person. It affects memory, attention span, communication, reasoning, judgement, problem solving and visual perception, etc. Signs that may point to dementia include getting lost in a familiar neighborhood, using unusual words to refer to familiar objects, forgetting the name of a close family member or friend, forgetting old memories, not being able to complete tasks independently, etc. [25]

Stages

The course of dementia is often described in four stages that show a pattern of progressive cognitive and functional impairment. However, the use of numeric scales allows for more detailed descriptions. These scales include the Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia (GDS or Reisberg Scale), the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST), and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).[26] Using the GDS, which more accurately identifies each stage of the disease progression, a more detailed course is described in seven stages – two of which are broken down further into five and six degrees. Stage 7(f) is the final stage.[27][28]

Pre-dementia

Pre-dementia states include pre-clinical and prodromal stages. The prodromal stages includes (1) mild cognitive impairment (MCI), (2) delirium-onset, and psychiatric-onset presentations.[29]

Pre-clinical

Sensory dysfunction is claimed for this stage which may precede the first clinical signs of dementia by up to ten years.[10] Most notably the sense of smell is lost.[10][30] The loss of the sense of smell is associated with depression and loss of appetite leading to poor nutrition.[31] It is suggested that this dysfunction may come about because the olfactory epithelium is exposed to the environment. The lack of blood–brain barrier protection here means that toxic elements can enter and cause damage to the chemosensory networks.[10]

Prodromal

Pre-dementia states considered as prodromal are mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and mild behavioral impairment (MBI).[32][33][34]

Kynurenine is a metabolite of tryptophan that regulates microbiome signalling, immune cell response, and neuronal excitation. A disruption in the kynurenine pathway may be associated with the neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive prognosis in mild dementia.[35][36]

In this stage signs and symptoms may be subtle. Often, the early signs become apparent when looking back.[37] 70% of those diagnosed with MCI later progress to dementia.[12] In MCI, changes in the person's brain have been happening for a long time, but symptoms are just beginning to appear. These problems, however, are not severe enough to affect daily function. If and when they do, the diagnosis becomes dementia. They may have some memory trouble and trouble finding words, but they solve everyday problems and competently handle their life affairs.[38]

Mild cognitive impairment has been relisted in both DSM-5, and ICD-11, as mild neurocognitive disorders – milder forms of the major neurocognitive disorder (dementia) subtypes.[39]

Early

In the early stage of dementia, symptoms become noticeable to other people. In addition, the symptoms begin to interfere with daily activities, and will register a score on a Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE). MMSE scores are set at 24 to 30 for a normal cognitive rating and lower scores reflect severity of symptoms. The symptoms are dependent on the type of dementia. More complicated chores and tasks around the house or at work become more difficult. The person can usually still take care of themselves but may forget things like taking pills or doing laundry and may need prompting or reminders.[40]

The symptoms of early dementia usually include memory difficulty, but can also include some word-finding problems, and problems with executive functions of planning and organization.[41] Managing finances may prove difficult. Other signs might be getting lost in new places, repeating things, and personality changes.[42]

In some types of dementia, such as dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia, personality changes and difficulty with organization and planning may be the first signs.[43]

Middle

As dementia progresses, initial symptoms generally worsen. The rate of decline is different for each person. MMSE scores between 6–17 signal moderate dementia. For example, people with moderate Alzheimer's dementia lose almost all new information. People with dementia may be severely impaired in solving problems, and their social judgment is usually also impaired. They cannot usually function outside their own home, and generally should not be left alone. They may be able to do simple chores around the house but not much else, and begin to require assistance for personal care and hygiene beyond simple reminders.[12] A lack of insight into having the condition will become evident.[44][45]

Late

People with late-stage dementia typically turn increasingly inward and need assistance with most or all of their personal care. Persons with dementia in the late stages usually need 24-hour supervision to ensure their personal safety, and meeting of basic needs. If left unsupervised, they may wander or fall; may not recognize common dangers such as a hot stove; or may not realize that they need to use the bathroom and become incontinent.[38] They may not want to get out of bed, or may need assistance doing so. Commonly, the person no longer recognizes familiar faces. They may have significant changes in sleeping habits or have trouble sleeping at all.[12]

Changes in eating frequently occur. Cognitive awareness is needed for eating and swallowing and progressive cognitive decline results in eating and swallowing difficulties. This can cause food to be refused, or choked on, and help with feeding will often be required.[46] For ease of feeding, food may be liquidized into a thick purée. They may also struggle to walk, particularly among those with Alzheimer's disease.[47][48][49]

Subtypes

Many of the subtypes of dementia are neurodegenerative, and protein toxicity is a cardinal feature of these.[50]

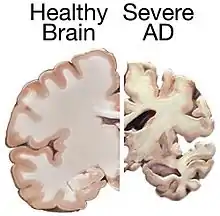

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60–70% of cases of dementia worldwide. The most common symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are short-term memory loss and word-finding difficulties. Trouble with visuospatial functioning (getting lost often), reasoning, judgment and insight fail. Insight refers to whether or not the person realizes they have memory problems.

The part of the brain most affected by Alzheimer's is the hippocampus. Other parts that show atrophy (shrinking) include the temporal and parietal lobes. Although this pattern of brain shrinkage suggests Alzheimer's, it is variable and a brain scan is insufficient for a diagnosis. The relationship between general anesthesia and Alzheimer's in elderly people is unclear.

Little is known about the events that occur during and that actually cause Alzheimer's disease. This is due to the fact that brain tissue from patients with the disease can only be studied after the person's death. However, it is known that one of the first aspects of the disease is a dysfunction in the gene that produces amyloid. Extracellular senile plaques (SPs), consisting of beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptides, and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) that are formed by hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, are two well-established pathological hallmarks of AD.[51] Amyloid causes inflammation around the senile plaques of the brain, and too much build up of this inflammation leads to changes in the brain that cannot be controlled, leading to the symptoms of Alzheimer's.[52]

Vascular

Vascular dementia accounts for at least 20% of dementia cases, making it the second most common type.[53] It is caused by disease or injury affecting the blood supply to the brain, typically involving a series of mini-strokes. The symptoms of this dementia depend on where in the brain the strokes occurred and whether the blood vessels affected were large or small.[12] Multiple injuries can cause progressive dementia over time, while a single injury located in an area critical for cognition such as the hippocampus, or thalamus, can lead to sudden cognitive decline.[53] Elements of vascular dementia may be present in all other forms of dementia.[54]

Brain scans may show evidence of multiple strokes of different sizes in various locations. People with vascular dementia tend to have risk factors for disease of the blood vessels, such as tobacco use, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol, diabetes, or other signs of vascular disease such as a previous heart attack or angina.[55]

Lewy bodies

The prodromal symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) include mild cognitive impairment, and delirium onset.[56] The symptoms of DLB are more frequent, more severe, and earlier presenting than in the other dementia subtypes.[57] Dementia with Lewy bodies has the primary symptoms of fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention; REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD); one or more of the main features of parkinsonism, not due to medication or stroke; and repeated visual hallucinations.[58] The visual hallucinations in DLB are generally vivid hallucinations of people or animals and they often occur when someone is about to fall asleep or wake up. Other prominent symptoms include problems with planning (executive function) and difficulty with visual-spatial function,[12] and disruption in autonomic bodily functions.[59] Abnormal sleep behaviors may begin before cognitive decline is observed and are a core feature of DLB.[58] RBD is diagnosed either by sleep study recording or, when sleep studies cannot be performed, by medical history and validated questionnaires.[58]

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is a Lewy body disease that often progresses to Parkinson's disease dementia following a period of dementia-free Parkinson's disease.[60]

Frontotemporal

Frontotemporal dementias (FTDs) are characterized by drastic personality changes and language difficulties. In all FTDs, the person has a relatively early social withdrawal and early lack of insight. Memory problems are not a main feature.[12][61] There are six main types of FTD. The first has major symptoms in personality and behavior. This is called behavioral variant FTD (bv-FTD) and is the most common. The hallmark feature of bv-FTD is impulsive behavior, and this can be detected in pre-dementia states.[34] In bv-FTD, the person shows a change in personal hygiene, becomes rigid in their thinking, and rarely acknowledges problems; they are socially withdrawn, and often have a drastic increase in appetite. They may become socially inappropriate. For example, they may make inappropriate sexual comments, or may begin using pornography openly. One of the most common signs is apathy, or not caring about anything. Apathy, however, is a common symptom in many dementias.[12]

Two types of FTD feature aphasia (language problems) as the main symptom. One type is called semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (SV-PPA). The main feature of this is the loss of the meaning of words. It may begin with difficulty naming things. The person eventually may lose the meaning of objects as well. For example, a drawing of a bird, dog, and an airplane in someone with FTD may all appear almost the same.[12] In a classic test for this, a patient is shown a picture of a pyramid and below it a picture of both a palm tree and a pine tree. The person is asked to say which one goes best with the pyramid. In SV-PPA the person cannot answer that question. The other type is called non-fluent agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (NFA-PPA). This is mainly a problem with producing speech. They have trouble finding the right words, but mostly they have a difficulty coordinating the muscles they need to speak. Eventually, someone with NFA-PPA only uses one-syllable words or may become totally mute.

A frontotemporal dementia associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) known as (FTD-ALS) includes the symptoms of FTD (behavior, language and movement problems) co-occurring with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (loss of motor neurons). Two FTD-related disorders are progressive supranuclear palsy (also classed as a Parkinson-plus syndrome),[62][63] and corticobasal degeneration.[12] These disorders are tau-associated.

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease is a neurodegenerative disease caused by mutations in a single gene HTT, that encodes for huntingtin protein. Symptoms include cognitive impairment and this usually declines further into dementia.[64]

The first main symptoms of Huntington's disease often include:

- difficulty concentrating

- memory lapses

- depression - this can include low mood, lack of interest in things, or just abnormal feelings of hopelessness

- stumbling and clumsiness that is out of the ordinary

- mood swings, such as irritability or aggressive behavior to insignificant things[65]

HIV

HIV-associated dementia results as a late stage from HIV infection, and mostly affects younger people.[66] The essential features of HIV-associated dementia are disabling cognitive impairment accompanied by motor dysfunction, speech problems and behavioral change.[66] Cognitive impairment is characterised by mental slowness, trouble with memory and poor concentration. Motor symptoms include a loss of fine motor control leading to clumsiness, poor balance and tremors. Behavioral changes may include apathy, lethargy and diminished emotional responses and spontaneity. Histopathologically, it is identified by the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into the central nervous system (CNS), gliosis, pallor of myelin sheaths, abnormalities of dendritic processes and neuronal loss.[67]

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease is a rapidly progressive prion disease that typically causes dementia that worsens over weeks to months. Prions are disease-causing pathogens created from abnormal proteins.[68]

Alcoholism

Alcohol-related dementia, also called alcohol-related brain damage, occurs as a result of excessive use of alcohol particularly as a substance abuse disorder. Different factors can be involved in this development including thiamine deficiency and age vulnerability.[69][70] A degree of brain damage is seen in more than 70% of those with alcohol use disorder. Brain regions affected are similar to those that are affected by aging, and also by Alzheimer's disease. Regions showing loss of volume include the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, as well as the cerebellum, thalamus, and hippocampus.[70] This loss can be more notable, with greater cognitive impairments seen in those aged 65 years and older.[70]

Mixed dementia

More than one type of dementia, known as mixed dementia, may exist together in about 10% of dementia cases.[2] The most common type of mixed dementia is Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.[71] This particular type of mixed dementia's main onsets are a mixture of old age, high blood pressure, and damage to blood vessels in the brain.[72]

Diagnosis of mixed dementia can be difficult, as often only one type will predominate. This makes the treatment of people with mixed dementia uncommon, with many people missing out on potentially helpful treatments. Mixed dementia can mean that symptoms onset earlier, and worsen more quickly since more parts of the brain will be affected.[72]

Genetics

Although it is not very common to inherit dementia from a parent or grandparent, there are genetic linked causes of dementia. These are only a small overall portion of the overall cases of dementia, but it is possible.[73]

Other

Chronic inflammatory conditions that may affect the brain and cognition include Behçet's disease, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, Sjögren's syndrome, lupus, celiac disease, and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.[74][75] These types of dementias can rapidly progress, but usually have a good response to early treatment. This consists of immunomodulators or steroid administration, or in certain cases, the elimination of the causative agent.[75] A 2019 review found no association between celiac disease and dementia overall but a potential association with vascular dementia.[76] A 2018 review found a link between celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity and cognitive impairment and that celiac disease may be associated with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia.[77] A strict gluten-free diet started early may protect against dementia associated with gluten-related disorders.[76][77]

Cases of easily reversible dementia include hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, Lyme disease, and neurosyphilis. For Lyme disease and neurosyphilis, testing should be done if risk factors are present. Because risk factors are often difficult to determine, testing for neurosyphilis and Lyme disease, as well as other mentioned factors, may be undertaken as a matter of course where dementia is suspected.[12]: 31–32

Many other medical and neurological conditions include dementia only late in the illness. For example, a proportion of patients with Parkinson's disease develop dementia, though widely varying figures are quoted for this proportion.[78] When dementia occurs in Parkinson's disease, the underlying cause may be dementia with Lewy bodies or Alzheimer's disease, or both.[79] Cognitive impairment also occurs in the Parkinson-plus syndromes of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration (and the same underlying pathology may cause the clinical syndromes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration). Although the acute porphyrias may cause episodes of confusion and psychiatric disturbance, dementia is a rare feature of these rare diseases. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) is a type of dementia that primarily affects people in their 80s or 90s and in which TDP-43 protein deposits in the limbic portion of the brain.[80]

Hereditary disorders that can also cause dementia include: some metabolic disorders, lysosomal storage disorders, leukodystrophies, and spinocerebellar ataxias.

Diagnosis

Symptoms are similar across dementia types and it is difficult to diagnose by symptoms alone. Diagnosis may be aided by brain scanning techniques. In many cases, the diagnosis requires a brain biopsy to become final, but this is rarely recommended (though it can be performed at autopsy). In those who are getting older, general screening for cognitive impairment using cognitive testing or early diagnosis of dementia has not been shown to improve outcomes.[14][81] However, screening exams are useful in 65+ persons with memory complaints.[12]

Normally, symptoms must be present for at least six months to support a diagnosis.[82] Cognitive dysfunction of shorter duration is called delirium. Delirium can be easily confused with dementia due to similar symptoms. Delirium is characterized by a sudden onset, fluctuating course, a short duration (often lasting from hours to weeks), and is primarily related to a somatic (or medical) disturbance. In comparison, dementia has typically a long, slow onset (except in the cases of a stroke or trauma), slow decline of mental functioning, as well as a longer trajectory (from months to years).[83]

Some mental illnesses, including depression and psychosis, may produce symptoms that must be differentiated from both delirium and dementia.[84] These are differently diagnosed as pseudodementias, and any dementia evaluation needs to include a depression screening such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory or the Geriatric Depression Scale.[85][12] Physicians used to think that people with memory complaints had depression and not dementia (because they thought that those with dementia are generally unaware of their memory problems). However, researchers have realized that many older people with memory complaints in fact have mild cognitive impairment the earliest stage of dementia. Depression should always remain high on the list of possibilities, however, for an elderly person with memory trouble. Changes in thinking, hearing and vision are associated with normal ageing and can cause problems when diagnosing dementia due to the similarities.[86] Given the challenging nature of predicting the onset of dementia and making a dementia diagnosis clinical decision making aids underpinned by machine learning and artificial intelligence have the potential to enhance clinical practice.[87]

Cognitive testing

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference |

| MMSE | 71–92% | 56–96% | [88] |

| 3MS | 83–93% | 85–90% | [89] |

| AMTS | 73–100% | 71–100% | [89] |

Various brief cognitive tests (5–15 minutes) have reasonable reliability to screen for dementia, but may be affected by factors such as age, education and ethnicity.[90] While many tests have been studied,[91][92][93] presently the mini mental state examination (MMSE) is the best studied and most commonly used. The MMSE is a useful tool for helping to diagnose dementia if the results are interpreted along with an assessment of a person's personality, their ability to perform activities of daily living, and their behaviour.[4] Other cognitive tests include the abbreviated mental test score (AMTS), the, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS),[94] the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI),[95] the Trail-making test,[96] and the clock drawing test.[26] The MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) is a reliable screening test and is available online for free in 35 different languages.[12] The MoCA has also been shown somewhat better at detecting mild cognitive impairment than the MMSE.[97][33] The AD-8 – a screening questionnaire used to assess changes in function related to cognitive decline – is potentially useful, but is not diagnostic, is variable, and has risk of bias.[98] An integrated cognitive assessment (CognICA) is a five-minute test that is highly sensitive to the early stages of dementia, and uses an application deliverable to an iPad.[99][100] Previously in use in the UK, in 2021 CognICA was given FDA approval for its commercial use as a medical device.[100]

Another approach to screening for dementia is to ask an informant (relative or other supporter) to fill out a questionnaire about the person's everyday cognitive functioning. Informant questionnaires provide complementary information to brief cognitive tests. Probably the best known questionnaire of this sort is the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE).[101] Evidence is insufficient to determine how accurate the IQCODE is for diagnosing or predicting dementia.[102] The Alzheimer's Disease Caregiver Questionnaire is another tool. It is about 90% accurate for Alzheimer's when by a caregiver.[12] The General Practitioner Assessment Of Cognition combines both a patient assessment and an informant interview. It was specifically designed for use in the primary care setting.

Clinical neuropsychologists provide diagnostic consultation following administration of a full battery of cognitive testing, often lasting several hours, to determine functional patterns of decline associated with varying types of dementia. Tests of memory, executive function, processing speed, attention and language skills are relevant, as well as tests of emotional and psychological adjustment. These tests assist with ruling out other etiologies and determining relative cognitive decline over time or from estimates of prior cognitive abilities.

Laboratory tests

Routine blood tests are usually performed to rule out treatable causes. These include tests for vitamin B12, folic acid, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), C-reactive protein, full blood count, electrolytes, calcium, renal function, and liver enzymes. Abnormalities may suggest vitamin deficiency, infection, or other problems that commonly cause confusion or disorientation in the elderly.[103]

Imaging

A CT scan or MRI scan is commonly performed to possibly find either normal pressure hydrocephalus, a potentially reversible cause of dementia, or connected tumor. The scans can also yield information relevant to other types of dementia, such as infarction (stroke) that would point at a vascular type of dementia. These tests do not pick up diffuse metabolic changes associated with dementia in a person who shows no gross neurological problems (such as paralysis or weakness) on a neurological exam.[104]

The functional neuroimaging modalities of SPECT and PET are more useful in assessing long-standing cognitive dysfunction, since they have shown similar ability to diagnose dementia as a clinical exam and cognitive testing.[105] The ability of SPECT to differentiate vascular dementia from Alzheimer's disease, appears superior to differentiation by clinical exam.[106]

The value of PiB-PET imaging using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) as a radiotracer has been established in predictive diagnosis, particularly Alzheimer's disease.[107]

Prevention

Risk factors

An influential review increased the number of associated risk factors for dementia from nine to twelve in 2020.[7] The three newly added risks are over-indulgence in alcohol, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution.[7] The other nine risk factors are: lower levels of education, high blood pressure, hearing loss, smoking, obesity, depression, inactivity, diabetes, and low social contact.[7] Many of these identified risk factors including, the lower level of education, smoking, physical inactivity and diabetes, are modifiable.[108] Several of the group are known vascular risk factors that may be able to be reduced or eliminated.[109] Managing these risk factors can reduce the risk of dementia in individuals in their late midlife or older age. A reduction in a number of these risk factors can give a positive outcome.[110] The decreased risk achieved by adopting a healthy lifestyle is seen even in those with a high genetic risk.[111]

In addition to the above risk factors, meta-analyses indicate that there is robust evidence that other psychological traits, including personality (high neuroticism, and low conscientiousness), low purpose in life, and high loneliness, are risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias.[112][113][114] For example, based on the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), research found that loneliness in older people increased the risk of dementia by one-third. Not having a partner (being single, divorced, or widowed) doubled the risk of dementia. However, having two or three closer relationships reduced the risk by three-fifths.[115][116]

The two most modifiable risk factors for dementia are physical inactivity and lack of cognitive stimulation.[117] Physical activity, in particular aerobic exercise, is associated with a reduction in age-related brain tissue loss, and neurotoxic factors thereby preserving brain volume and neuronal integrity. Cognitive activity strengthens neural plasticity and together they help to support cognitive reserve. The neglect of these risk factors diminishes this reserve.[117]

Studies suggest that sensory impairments of vision and hearing are modifiable risk factors for dementia.[118] These impairments may precede the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease for example, by many years.[119] Hearing loss may lead to social isolation which negatively affects cognition.[120] Social isolation is also identified as a modifiable risk factor.[119] Age-related hearing loss in midlife is linked to cognitive impairment in late life, and is seen as a risk factor for the development of Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Such hearing loss may be caused by a central auditory processing disorder that makes the understanding of speech against background noise difficult. Age-related hearing loss is characterised by slowed central processing of auditory information.[119][121] Worldwide, mid-life hearing loss may account for around 9% of dementia cases.[122]

Evidence suggests that frailty may increase the risk of cognitive decline, and dementia, and that the inverse also holds of cognitive impairment increasing the risk of frailty. Prevention of frailty may help to prevent cognitive decline.[119]

A 2018 review however concluded that no medications have good evidence of a preventive effect, including blood pressure medications.[123] A 2020 review found a decrease in the risk of dementia or cognitive problems from 7.5% to 7.0% with blood pressure lowering medications.[124]

Economic disadvantage has been shown to have a strong link to higher dementia prevalence,[125] which cannot yet be fully explained by other risk factors.

Dental health

Limited evidence links poor oral health to cognitive decline. However, failure to perform tooth brushing and gingival inflammation can be used as dementia risk predictors.[126]

Oral bacteria

The link between Alzheimer's and gum disease is oral bacteria.[127] In the oral cavity, bacterial species include P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and T. forsythia. Six oral treponema spirochetes have been examined in the brains of Alzheimer's patients.[128] Spirochetes are neurotropic in nature, meaning they act to destroy nerve tissue and create inflammation. Inflammatory pathogens are an indicator of Alzheimer's disease and bacteria related to gum disease have been found in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease.[128] The bacteria invade nerve tissue in the brain, increasing the permeability of the blood–brain barrier and promoting the onset of Alzheimer's. Individuals with a plethora of tooth plaque risk cognitive decline.[129] Poor oral hygiene can have an adverse effect on speech and nutrition, causing general and cognitive health decline.

Oral viruses

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been found in more than 70% of those aged over 50. HSV persists in the peripheral nervous system and can be triggered by stress, illness or fatigue.[128] High proportions of viral-associated proteins in amyloid plaques or neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) confirm the involvement of HSV-1 in Alzheimer's disease pathology. NFTs are known as the primary marker of Alzheimer's disease. HSV-1 produces the main components of NFTs.[130]

Diet

Diet is seen to be a modifiable risk factor for the development of dementia. Thiamine deficiency is identified to increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease in adults.[131] The role of thiamine in brain physiology is unique and essential for the normal cognitive function of older people.[132] Many dietary choices of the elderly population, including the higher intake of gluten-free products, compromise the intake of thiamine as these products are not fortified with thiamine.[133]

The Mediterranean and DASH diets are both associated with less cognitive decline. A different approach has been to incorporate elements of both of these diets into one known as the MIND diet.[134] These diets are generally low in saturated fats while providing a good source of carbohydrates, mainly those that help stabilize blood sugar and insulin levels.[135] Raised blood sugar levels over a long time, can damage nerves and cause memory problems if they are not managed.[136] Nutritional factors associated with the proposed diets for reducing dementia risk include unsaturated fatty acids, vitamin E, vitamin C, flavonoids, vitamin B, and vitamin D.[137][138]

The MIND diet may be more protective but further studies are needed. The Mediterranean diet seems to be more protective against Alzheimer's than DASH but there are no consistent findings against dementia in general. The role of olive oil needs further study as it may be one of the most important components in reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.[134][139]

In those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, a strict gluten-free diet may relieve the symptoms given a mild cognitive impairment.[76][77] Once dementia is advanced no evidence suggests that a gluten-free diet is useful.[76]

Omega-3 fatty acid supplements do not appear to benefit or harm people with mild to moderate symptoms.[140] However, there is good evidence that omega-3 incorporation into the diet is of benefit in treating depression, a common symptom,[141] and potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia.[7]

Management

There are limited options for treating dementia, with most approaches focused on managing or reducing individual symptoms. There are no treatment options available to delay the onset of dementia.[142] Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are often used early in the disorder course; however, benefit is generally small.[8][143] More than half of people with dementia may experience psychological or behavioral symptoms including agitation, sleep problems, aggression, and/or psychosis. Treatment for these symptoms is aimed at reducing the person's distress and keeping the person safe. Treatments other than medication appear to be better for agitation and aggression.[144] Cognitive and behavioral interventions may be appropriate. Some evidence suggests that education and support for the person with dementia, as well as caregivers and family members, improves outcomes.[145] Palliative care interventions may improve lead to improvements in comfort in dying, but the evidence is low.[146] Exercise programs are beneficial with respect to activities of daily living, and potentially improve dementia.[147]

The effect of therapies can be evaluated for example by assessing agitation using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI); by assessing mood and engagement with the Menorah Park Engagement Scale (MPES);[148] and the Observed Emotion Rating Scale (OERS)[149] or by assessing indicators for depression using the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD)[150] or a simplified version thereof.[151]

Often overlooked in treating and managing dementia is the role of the caregiver and what is known about how they can support multiple interventions. Findings from a 2021 systematic review of the literature found caregivers of people with dementia in nursing homes do not have sufficient tools or clinical guidance for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) along with medication use.[152] Simple measures like talking to people about their interest can improve the quality of life for care home residents living with dementia. A programme showed that such simple measures reduced residents' agitation and depression. They also needed fewer GP visits and hospital admissions, which also meant that the programme was cost-saving.[153][154]

Psychological and psychosocial therapies

Psychological therapies for dementia include some limited evidence for reminiscence therapy (namely, some positive effects in the areas of quality of life, cognition, communication and mood – the first three particularly in care home settings),[155] some benefit for cognitive reframing for caretakers,[156] unclear evidence for validation therapy[157] and tentative evidence for mental exercises, such as cognitive stimulation programs for people with mild to moderate dementia.[158] Offering personally tailored activities may help reduce challenging behavior and may improve quality of life.[159] It is not clear if personally tailored activities have an impact on affect or improve for the quality of life for the caregiver.[159]

Adult daycare centers as well as special care units in nursing homes often provide specialized care for dementia patients. Daycare centers offer supervision, recreation, meals, and limited health care to participants, as well as providing respite for caregivers. In addition, home care can provide one-to-one support and care in the home allowing for more individualized attention that is needed as the disorder progresses. Psychiatric nurses can make a distinctive contribution to people's mental health.[160]

Since dementia impairs normal communication due to changes in receptive and expressive language, as well as the ability to plan and problem solve, agitated behavior is often a form of communication for the person with dementia. Actively searching for a potential cause, such as pain, physical illness, or overstimulation can be helpful in reducing agitation.[161] Additionally, using an "ABC analysis of behavior" can be a useful tool for understanding behavior in people with dementia. It involves looking at the antecedents (A), behavior (B), and consequences (C) associated with an event to help define the problem and prevent further incidents that may arise if the person's needs are misunderstood.[162] The strongest evidence for non-pharmacological therapies for the management of changed behaviors in dementia is for using such approaches.[163] Low quality evidence suggests that regular (at least five sessions of) music therapy may help institutionalized residents. It may reduce depressive symptoms and improve overall behaviors. It may also supply a beneficial effect on emotional well-being and quality of life, as well as reduce anxiety.[164] In 2003, The Alzheimer's Society established 'Singing for the Brain' (SftB) a project based on pilot studies which suggested that the activity encouraged participation and facilitated the learning of new songs. The sessions combine aspects of reminiscence therapy and music.[165] Musical and interpersonal connectedness can underscore the value of the person and improve quality of life.[166]

Some London hospitals found that using color, designs, pictures and lights helped people with dementia adjust to being at the hospital. These adjustments to the layout of the dementia wings at these hospitals helped patients by preventing confusion.[167]

Life story work as part of reminiscence therapy, and video biographies have been found to address the needs of clients and their caregivers in various ways, offering the client the opportunity to leave a legacy and enhance their personhood and also benefitting youth who participate in such work. Such interventions can be more beneficial when undertaken at a relatively early stage of dementia. They may also be problematic in those who have difficulties in processing past experiences[166]

Animal-assisted therapy has been found to be helpful. Drawbacks may be that pets are not always welcomed in a communal space in the care setting. An animal may pose a risk to residents, or may be perceived to be dangerous. Certain animals may also be regarded as "unclean" or "dangerous" by some cultural groups.[166]

Occupational therapy also addresses psychological and psychosocial needs of patients with dementia through improving daily occupational performance and caregivers' competence.[168] When compensatory intervention strategies are added to their daily routine, the level of performance is enhanced and reduces the burden commonly placed on their caregivers.[168] Occupational therapists can also work with other disciplines to create a client centered intervention.[169] To manage cognitive disability, and coping with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, combined occupational and behavioral therapies can support patients with dementia even further.[169]

Cognitive training

There is no strong evidence to suggest that cognitive training is beneficial for people with Parkinson's disease, dementia, or mild cognitive impairment.[170]

Personally tailored activities

Offering personally tailored activity sessions to people with dementia in long-term care homes may help manage challenging behavior.[171]

Medications

No medications have been shown to prevent or cure dementia.[172] Medications may be used to treat the behavioral and cognitive symptoms, but have no effect on the underlying disease process.[12][173]

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may be useful for Alzheimer's disease,[174] Parkinson's disease dementia, DLB, or vascular dementia.[173] The quality of the evidence is poor[175] and the benefit is small.[8] No difference has been shown between the agents in this family.[176] In a minority of people side effects include a slow heart rate and fainting.[177] Rivastigmine is recommended for treating symptoms in Parkinson's disease dementia.[178]

Medications that have anticholinergic effects increase all-cause mortality in people with dementia, although the effect of these medications on cognitive function remains uncertain, according to a systematic review published in 2021.[179]

Before prescribing antipsychotic medication in the elderly, an assessment for an underlying cause of the behavior is needed.[180] Severe and life-threatening reactions occur in almost half of people with DLB,[59][181] and can be fatal after a single dose.[182] People with Lewy body dementias who take neuroleptics are at risk for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a life-threatening illness.[183] Extreme caution is required in the use of antipsychotic medication in people with DLB because of their sensitivity to these agents.[58] Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat dementia only if non-drug therapies have not worked, and the person's actions threaten themselves or others.[184][185][186][187] Aggressive behavior changes are sometimes the result of other solvable problems, that could make treatment with antipsychotics unnecessary.[184] Because people with dementia can be aggressive, resistant to their treatment, and otherwise disruptive, sometimes antipsychotic drugs are considered as a therapy in response.[184] These drugs have risky adverse effects, including increasing the person's chance of stroke and death.[184] Given these adverse events and small benefit antipsychotics are avoided whenever possible.[163] Generally, stopping antipsychotics for people with dementia does not cause problems, even in those who have been on them a long time.[188]

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockers such as memantine may be of benefit but the evidence is less conclusive than for AChEIs.[174] Due to their differing mechanisms of action memantine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can be used in combination however the benefit is slight.[189][190]

An extract of Ginkgo biloba known as EGb 761 has been widely used for treating mild to moderate dementia and other neuropsychiatric disorders.[191] Its use is approved throughout Europe.[192] The World Federation of Biological Psychiatry guidelines lists EGb 761 with the same weight of evidence (level B) given to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and mementine. EGb 761 is the only one that showed improvement of symptoms in both AD and vascular dementia. EGb 761 is seen as being able to play an important role either on its own or as an add-on particularly when other therapies prove ineffective.[191] EGb 761 is seen to be neuroprotective; it is a free radical scavenger, improves mitochondrial function, and modulates serotonin and dopamine levels. Many studies of its use in mild to moderate dementia have shown it to significantly improve cognitive function, activities of daily living, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and quality of life.[191][193] However, its use has not been shown to prevent the progression of dementia.[191]

While depression is frequently associated with dementia, the use of antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) do not appear to affect outcomes.[194][195] However, the SSRIs sertraline and citalopram have been demonstrated to reduce symptoms of agitation, compared to placebo.[196]

The use of medications to alleviate sleep disturbances that people with dementia often experience has not been well researched, even for medications that are commonly prescribed.[197] In 2012 the American Geriatrics Society recommended that benzodiazepines such as diazepam, and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, be avoided for people with dementia due to the risks of increased cognitive impairment and falls.[198] Benzodiazepines are also known to promote delirium.[199] Additionally, little evidence supports the effectiveness of benzodiazepines in this population.[197][200] No clear evidence shows that melatonin or ramelteon improves sleep for people with dementia due to Alzheimer's,[197] but it is used to treat REM sleep behavior disorder in dementia with Lewy bodies.[59] Limited evidence suggests that a low dose of trazodone may improve sleep, however more research is needed.[197]

No solid evidence indicates that folate or vitamin B12 improves outcomes in those with cognitive problems.[201] Statins have no benefit in dementia.[202] Medications for other health conditions may need to be managed differently for a person who has a dementia diagnosis. It is unclear whether blood pressure medication and dementia are linked. People may experience an increase in cardiovascular-related events if these medications are withdrawn.[203]

The Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health Conditions in Dementia (MATCH-D) criteria can help identify ways that a diagnosis of dementia changes medication management for other health conditions.[204] These criteria were developed because people with dementia live with an average of five other chronic diseases, which are often managed with medications. The systematic review that informed the criteria were published subsequently in 2018 and updated in 2022.[205]

Pain

As people age, they experience more health problems, and most health problems associated with aging carry a substantial burden of pain; therefore, between 25% and 50% of older adults experience persistent pain. Seniors with dementia experience the same prevalence of conditions likely to cause pain as seniors without dementia.[206] Pain is often overlooked in older adults and, when screened for, is often poorly assessed, especially among those with dementia, since they become incapable of informing others of their pain.[206][207] Beyond the issue of humane care, unrelieved pain has functional implications. Persistent pain can lead to decreased ambulation, depressed mood, sleep disturbances, impaired appetite, and exacerbation of cognitive impairment[207] and pain-related interference with activity is a factor contributing to falls in the elderly.[206][208]

Although persistent pain in people with dementia is difficult to communicate, diagnose, and treat, failure to address persistent pain has profound functional, psychosocial and quality of life implications for this vulnerable population. Health professionals often lack the skills and usually lack the time needed to recognize, accurately assess and adequately monitor pain in people with dementia.[206][209] Family members and friends can make a valuable contribution to the care of a person with dementia by learning to recognize and assess their pain. Educational resources and observational assessment tools are available.[206][210][211]

Eating difficulties

Persons with dementia may have difficulty eating. Whenever it is available as an option, the recommended response to eating problems is having a caretaker assist them.[184] A secondary option for people who cannot swallow effectively is to consider gastrostomy feeding tube placement as a way to give nutrition. However, in bringing comfort and maintaining functional status while lowering risk of aspiration pneumonia and death, assistance with oral feeding is at least as good as tube feeding.[184][212] Tube-feeding is associated with agitation, increased use of physical and chemical restraints and worsening pressure ulcers. Tube feedings may cause fluid overload, diarrhea, abdominal pain, local complications, less human interaction and may increase the risk of aspiration.[213][214]

Benefits in those with advanced dementia has not been shown.[215] The risks of using tube feeding include agitation, rejection by the person (pulling out the tube, or otherwise physical or chemical immobilization to prevent them from doing this), or developing pressure ulcers.[184] The procedure is directly related to a 1% fatality rate[216] with a 3% major complication rate.[217] The percentage of people at end of life with dementia using feeding tubes in the US has dropped from 12% in 2000 to 6% as of 2014.[218][219]

The immediate and long-term effects of modifying the thickness of fluids for swallowing difficulties in people with dementia are not well known.[220] While thickening fluids may have an immediate positive effect on swallowing and improving oral intake, the long-term impact on the health of the person with dementia should also be considered.[220]

Exercise

Exercise programs may improve the ability of people with dementia to perform daily activities, but the best type of exercise is still unclear.[221] Getting more exercise can slow the development of cognitive problems such as dementia, proving to reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease by about 50%. A balance of strength exercise, to help muscles pump blood to the brain, and balance exercises are recommended for aging people. A suggested amount of about 2+1⁄2 hours per week can reduce risks of cognitive decay as well as other health risks like falling.[222]

Assistive technology

There is a lack of high-quality evidence to determine whether assistive technology effectively supports people with dementia to manage memory issues.[223] Some of the specific things that are used today that helps with dementia today are: clocks, communication aids, electrical appliances the use monitoring, GPS location/ tracking devices, home care robots, in-home cameras, and medication management are just to name a few.[224]

Alternative medicine

Aromatherapy and massage have unclear evidence.[225][226] It is not clear if cannabinoids are harmful or effective for people with dementia.[227]

Palliative care

Given the progressive and terminal nature of dementia, palliative care can be helpful to patients and their caregivers by helping people with the disorder and their caregivers understand what to expect, deal with loss of physical and mental abilities, support the person's wishes and goals including surrogate decision making, and discuss wishes for or against CPR and life support.[228][229] Because the decline can be rapid, and because most people prefer to allow the person with dementia to make their own decisions, palliative care involvement before the late stages of dementia is recommended.[230][231] Further research is required to determine the appropriate palliative care interventions and how well they help people with advanced dementia.[146]

Person-centered care helps maintain the dignity of people with dementia.[232]

Remotely delivered information for caregivers

Remotely delivered interventions including support, training and information may reduce the burden for the informal caregiver and improve their depressive symptoms.[233] There is no certain evidence that they improve health-related quality of life.[233]

In several localities in Japan, digital surveillance may be made available to family members, if a dementia patient is prone to wandering and going missing.[234]

Epidemiology

<100 100–120 120–140 140–160 160–180 180–200 |

200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 >300 |

The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer's disease. Other common types include vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia, and mixed dementia (commonly Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia).[2][lower-alpha 2][178] Less common causes include normal pressure hydrocephalus, Parkinson's disease dementia, syphilis, HIV, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[238] The number of cases of dementia worldwide in 2021 was estimated at 55 million, with close to 10 million new cases each year.[2] By 2050, the number of people living with dementia is estimated to be over 150 million globally.[239] An estimated 58% of people with dementia are living in low and middle income countries.[240][241] The prevalence of dementia differs in different world regions, ranging from 4.7% in Central Europe to 8.7% in North Africa/Middle East; the prevalence in other regions is estimated to be between 5.6 and 7.6%.[240] The number of people living with dementia is estimated to double every 20 years. In 2016 dementia resulted in about 2.4 million deaths,[9] up from 0.8 million in 1990.[242]

The annual incidence of dementia diagnosis is nearly 10 million worldwide.[146] Almost half of new dementia cases occur in Asia, followed by Europe (25%), the Americas (18%) and Africa (8%). The incidence of dementia increases exponentially with age, doubling with every 6.3 year increase in age.[240] Dementia affects 5% of the population older than 65 and 20–40% of those older than 85.[243] Rates are slightly higher in women than men at ages 65 and greater.[243] The disease trajectory is varied and the median time from diagnosis to death depends strongly on age at diagnosis, from 6.7 years for people diagnosed aged 60–69 to 1.9 years for people diagnosed at 90 or older.[146]

Dementia impacts not only individuals with dementia, but also their carers and the wider society. Among people aged 60 years and over, dementia is ranked the 9th most burdensome condition according to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates. The global costs of dementia was around US$818 billion in 2015, a 35.4% increase from US$604 billion in 2010.[240]

Affected ages

About 3% of people between the ages of 65–74 have dementia, 19% between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age. As more people are living longer, dementia is becoming more common.[244] For people of a specific age, however, it may be becoming less frequent in the developed world, due to a decrease in modifiable risk factors made possible by greater financial and educational resources. It is one of the most common causes of disability among the elderly but can develop before the age of 65 when it is known as early-onset dementia or presenile dementia.[245][246] Less than 1% of those with Alzheimer's have gene mutations that cause a much earlier development of the disease, around the age of 45, known as early-onset Alzheimer's disease.[247] More than 95% of people with Alzheimer's disease have the sporadic form (late onset, 80–90 years of age).[247] Worldwide the cost of dementia in 2015 was put at US$818 billion. People with dementia are often physically or chemically restrained to a greater degree than necessary, raising issues of human rights.[2][248] Social stigma is commonly perceived by those with the condition, and also by their caregivers.[81]

History

Until the end of the 19th century, dementia was a much broader clinical concept. It included mental illness and any type of psychosocial incapacity, including reversible conditions.[249] Dementia at this time simply referred to anyone who had lost the ability to reason, and was applied equally to psychosis, "organic" diseases like syphilis that destroy the brain, and to the dementia associated with old age, which was attributed to "hardening of the arteries".

Dementia has been referred to in medical texts since antiquity. One of the earliest known allusions to dementia is attributed to the 7th-century BC Greek philosopher Pythagoras, who divided the human lifespan into six distinct phases: 0–6 (infancy), 7–21 (adolescence), 22–49 (young adulthood), 50–62 (middle age), 63–79 (old age), and 80–death (advanced age). The last two he described as the "senium", a period of mental and physical decay, and that the final phase was when "the scene of mortal existence closes after a great length of time that very fortunately, few of the human species arrive at, where the mind is reduced to the imbecility of the first epoch of infancy".[250] In 550 BC, the Athenian statesman and poet Solon argued that the terms of a man's will might be invalidated if he exhibited loss of judgement due to advanced age. Chinese medical texts made allusions to the condition as well, and the characters for "dementia" translate literally to "foolish old person".[251]

Athenian philosophers Aristotle and Plato discussed the mental decline that can come with old age and predicted that this affects everyone who becomes old and nothing can be done to stop this decline from taking place. Plato specifically talked about how the elderly should not be in positions that require responsibility because, "There is not much acumen of the mind that once carried them in their youth, those characteristics one would call judgement, imagination, power of reasoning, and memory. They see them gradually blunted by deterioration and can hardly fulfill their function."[252]

For comparison, the Roman statesman Cicero held a view much more in line with modern-day medical wisdom that loss of mental function was not inevitable in the elderly and "affected only those old men who were weak-willed". He spoke of how those who remained mentally active and eager to learn new things could stave off dementia. However, Cicero's views on aging, although progressive, were largely ignored in a world that would be dominated for centuries by Aristotle's medical writings. Physicians during the Roman Empire, such as Galen and Celsus, simply repeated the beliefs of Aristotle while adding few new contributions to medical knowledge.

Byzantine physicians sometimes wrote of dementia. It is recorded that at least seven emperors whose lifespans exceeded 70 years displayed signs of cognitive decline. In Constantinople, special hospitals housed those diagnosed with dementia or insanity, but these did not apply to the emperors, who were above the law and whose health conditions could not be publicly acknowledged.

Otherwise, little is recorded about dementia in Western medical texts for nearly 1700 years. One of the few references was the 13th-century friar Roger Bacon, who viewed old age as divine punishment for original sin. Although he repeated existing Aristotelian beliefs that dementia was inevitable, he did make the progressive assertion that the brain was the center of memory and thought rather than the heart.

Poets, playwrights, and other writers made frequent allusions to the loss of mental function in old age. William Shakespeare notably mentions it in plays such as Hamlet and King Lear.

During the 19th century, doctors generally came to believe that elderly dementia was the result of cerebral atherosclerosis, although opinions fluctuated between the idea that it was due to blockage of the major arteries supplying the brain or small strokes within the vessels of the cerebral cortex.

In 1907, Bavarian psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer was the first to identify and describe the characteristics of progressive dementia in the brain of 51-year-old Auguste Deter.[253] Deter had begun to behave uncharacteristically, including accusing her husband of adultery, neglecting household chores, exhibiting difficulties writing and engaging in conversations, heightened insomnia, and loss of directional sense.[254] At one point, Deter was reported to have "dragged a bed sheet outside, wandered around wildly, and cried for hours at midnight."[254] Alzheimer began treating Deter when she entered a Frankfurt mental hospital on November 25, 1901.[254] During her ongoing treatment, Deter and her husband struggled to afford the cost of the medical care, and Alzheimer agreed to continue her treatment in exchange for Deter's medical records and donation of her brain upon death.[254] Deter died on April 8, 1906, after succumbing to sepsis and pneumonia.[254] Alzheimer conducted the brain biopsy using the Bielschowsky stain method, which was a new development at the time, and he observed senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and atherosclerotic alteration.[253] At the time, the consensus among medical doctors had been that senile plaques were generally found in older patients, and the occurrence of neurofibrillary tangles was an entirely new observation at the time.[254] Alzheimer presented his findings at the 37th psychiatry conference of southwestern Germany in Tübingen on April 11, 1906; however, the information was poorly received by his peers.[254] By 1910, Alois Alzheimer's teacher, Emil Kraepelin, published a book in which he coined the term "Alzheimer's disease" in an attempt to acknowledge the importance of Alzheimer's discovery.[253][254]

By the 1960s, the link between neurodegenerative diseases and age-related cognitive decline had become more established. By the 1970s, the medical community maintained that vascular dementia was rarer than previously thought and Alzheimer's disease caused the vast majority of old age mental impairments. More recently however, it is believed that dementia is often a mixture of conditions.

In 1976, neurologist Robert Katzmann suggested a link between senile dementia and Alzheimer's disease.[255] Katzmann suggested that much of the senile dementia occurring (by definition) after the age of 65, was pathologically identical with Alzheimer's disease occurring in people under age 65 and therefore should not be treated differently.[256] Katzmann thus suggested that Alzheimer's disease, if taken to occur over age 65, is actually common, not rare, and was the fourth- or 5th-leading cause of death, even though rarely reported on death certificates in 1976.

A helpful finding was that although the incidence of Alzheimer's disease increased with age (from 5–10% of 75-year-olds to as many as 40–50% of 90-year-olds), no threshold was found by which age all persons developed it. This is shown by documented supercentenarians (people living to 110 or more) who experienced no substantial cognitive impairment. Some evidence suggests that dementia is most likely to develop between ages 80 and 84 and individuals who pass that point without being affected have a lower chance of developing it. Women account for a larger percentage of dementia cases than men, although this can be attributed to their longer overall lifespan and greater odds of attaining an age where the condition is likely to occur.[257]

Much like other diseases associated with aging, dementia was comparatively rare before the 20th century, because few people lived past 80. Conversely, syphilitic dementia was widespread in the developed world until it was largely eradicated by the use of penicillin after World War II. With significant increases in life expectancy thereafter, the number of people over 65 started rapidly climbing. While elderly persons constituted an average of 3–5% of the population prior to 1945, by 2010 many countries reached 10–14% and in Germany and Japan, this figure exceeded 20%. Public awareness of Alzheimer's Disease greatly increased in 1994 when former US president Ronald Reagan announced that he had been diagnosed with the condition.

In the 21st century, other types of dementia were differentiated from Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementias (the most common types). This differentiation is on the basis of pathological examination of brain tissues, by symptomatology, and by different patterns of brain metabolic activity in nuclear medical imaging tests such as SPECT and PETscans of the brain. The various forms have differing prognoses and differing epidemiologic risk factors. The main cause for many diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, remains unclear.[258]

Terminology

Dementia in the elderly was once called senile dementia or senility, and viewed as a normal and somewhat inevitable aspect of aging.[259][260]

By 1913–20 the term dementia praecox was introduced to suggest the development of senile-type dementia at a younger age. Eventually the two terms fused, so that until 1952 physicians used the terms dementia praecox (precocious dementia) and schizophrenia interchangeably. Since then, science has determined that dementia and schizophrenia are two different disorders, though they share some similarities.[261] The term precocious dementia for a mental illness suggested that a type of mental illness like schizophrenia (including paranoia and decreased cognitive capacity) could be expected to arrive normally in all persons with greater age (see paraphrenia). After about 1920, the beginning use of dementia for what is now understood as schizophrenia and senile dementia helped limit the word's meaning to "permanent, irreversible mental deterioration". This began the change to the later use of the term. In recent studies, researchers have seen a connection between those diagnosed with schizophrenia and patients who are diagnosed with dementia, finding a positive correlation between the two diseases.[262]

The view that dementia must always be the result of a particular disease process led for a time to the proposed diagnosis of "senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type" (SDAT) in persons over the age of 65, with "Alzheimer's disease" diagnosed in persons younger than 65 who had the same pathology. Eventually, however, it was agreed that the age limit was artificial, and that Alzheimer's disease was the appropriate term for persons with that particular brain pathology, regardless of age.

After 1952, mental illnesses including schizophrenia were removed from the category of organic brain syndromes, and thus (by definition) removed from possible causes of "dementing illnesses" (dementias). At the same, however, the traditional cause of senile dementia – "hardening of the arteries" – now returned as a set of dementias of vascular cause (small strokes). These were now termed multi-infarct dementias or vascular dementias.

Society and culture

.jpg.webp)

The societal cost of dementia is high, especially for caregivers.[263] According to a UK-based study, almost two out of three carers of people with dementia feel lonely. Most of the carers in the study were family members or friends.[264][265]

As of 2015, the annual cost per Alzheimer's patient in the United States was around $19,144.36. The total costs for the nation is estimated to be about $167.74 billion. By 2030, it is predicted the annual socioeconomic cost will total to about $507 billion, and by 2050 that number is expected to reach $1.89 trillion. This steady increase will be seen not just within the United States but globally. Global estimates for the costs of dementia were $957.56 billion in 2015, but by 2050 the estimated global cost is 9.12 trillion.[266]

Many countries consider the care of people living with dementia a national priority and invest in resources and education to better inform health and social service workers, unpaid caregivers, relatives and members of the wider community. Several countries have authored national plans or strategies.[267][268] These plans recognize that people can live reasonably with dementia for years, as long as the right support and timely access to a diagnosis are available. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron described dementia as a "national crisis", affecting 800,000 people in the United Kingdom.[269] In fact, dementia has become the leading cause of death for women in England.[270]

There, as with all mental disorders, people with dementia could potentially be a danger to themselves or others, they can be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 for assessment, care and treatment. This is a last resort, and is usually avoided by people with family or friends who can ensure care.

Some hospitals in Britain work to provide enriched and friendlier care. To make the hospital wards calmer and less overwhelming to residents, staff replaced the usual nurses' station with a collection of smaller desks, similar to a reception area. The incorporation of bright lighting helps increase positive mood and allow residents to see more easily.[271]

Driving with dementia can lead to injury or death. Doctors should advise appropriate testing on when to quit driving.[272] The United Kingdom DVLA (Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency) states that people with dementia who specifically have poor short-term memory, disorientation, or lack of insight or judgment are not allowed to drive, and in these instances the DVLA must be informed so that the driving license can be revoked. They acknowledge that in low-severity cases and those with an early diagnosis, drivers may be permitted to continue driving.

Many support networks are available to people with dementia and their families and caregivers. Charitable organizations aim to raise awareness and campaign for the rights of people living with dementia. Support and guidance are available on assessing testamentary capacity in people with dementia.[273]

In 2015, Atlantic Philanthropies announced a $177 million gift aimed at understanding and reducing dementia. The recipient was Global Brain Health Institute, a program co-led by the University of California, San Francisco and Trinity College Dublin. This donation is the largest non-capital grant Atlantic has ever made, and the biggest philanthropic donation in Irish history.[274]

In October 2020, the Caretaker's last music release, Everywhere at the End of Time, was popularized by TikTok users for its depiction of the stages of dementia.[275] Caregivers were in favor of this phenomenon; Leyland Kirby, the creator of the record, echoed this sentiment, explaining it could cause empathy among a younger public.[276]

On 2 November 2020, Scottish billionaire Sir Tom Hunter donated £1 million to dementia charities, after watching a former music teacher with dementia, Paul Harvey, playing one of his own compositions on the piano in a viral video. The donation was announced to be split between the Alzheimer's Society and Music for Dementia.[277]

Notes

- Prodromal subtypes of delirium-onset dementia with Lewy bodies have been proposed as of 2020.[11]

- Kosaka (2017) writes: "Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is now well known to be the second most frequent dementia following Alzheimer disease (AD). Of all types of dementia, AD is known to account for about 50%, DLB about 20% and vascular dementia (VD) about 15%. Thus, AD, DLB, and VD are now considered to be the three major dementias."[235] The NINDS (2020) says that Lewy body dementia "is one of the most common causes of dementia, after Alzheimer's disease and vascular disease."[236] Hershey (2019) says, "DLB is the third most common of all the neurodegenerative diseases behind both Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease".[237]

References

- "Dementia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- "Dementia". www.who.int. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Dementia". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, et al. (January 2016). "Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD011145. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011145.pub2. hdl:1983/00876aeb-2061-43f5-b7e1-938c666030ab. PMC 8812342. PMID 26760674.

- "Differential diagnosis dementia". NICE. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Hales RE (2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. (August 2020). "Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission". Lancet. 396 (10248): 413–446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. PMC 7392084. PMID 32738937.

- Commission de la transparence (June 2012). "Drugs for Alzheimer's disease: best avoided. No therapeutic advantage" [Drugs for Alzheimer's disease: best avoided. No therapeutic advantage]. Prescrire International. 21 (128): 150. PMID 22822592.

- Nichols E, Szoeke CE, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, et al. (GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators) (January 2019). "Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. Neurology. 18 (1): 88–106. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4. PMC 6291454. PMID 30497964.

- Bathini P, Brai E, Auber LA (November 2019). "Olfactory dysfunction in the pathophysiological continuum of dementia" (PDF). Ageing Research Reviews. 55: 100956. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2019.100956. PMID 31479764. S2CID 201742825.

- McKeith IG, Ferman TJ, Thomas AJ, et al. (April 2020). "Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies". Neurology (Review). 94 (17): 743–755. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009323. PMC 7274845. PMID 32241955.

- Budson A, Solomon P (2011). Memory loss : a practical guide for clinicians. [Edinburgh?]: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-3597-8.

- "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Lin JS, O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Perdue LA, Eckstrom E (November 2013). "Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (9): 601–612. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00730. PMID 24145578.