Sustainable development

Sustainable development is an organizing principle for meeting human development goals while also sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services on which the economy and society depend. The desired result is a state of society where living conditions and resources are used to continue to meet human needs without undermining the integrity and stability of the natural system. Sustainable development was defined in the 1987 Brundtland Report as "development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".[2][3] As the concept of sustainable development developed, it has shifted its focus more towards the economic development, social development and environmental protection for future generations.

Sustainable development was first institutionalized with the Rio Process initiated at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. In 2015 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (2015 to 2030) and explained how the goals are integrated and indivisible to achieve sustainable development at the global level.[4] The 17 goals address the global challenges, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice.

Sustainable development is interlinked with the normative concept of sustainability. UNESCO formulated a distinction between the two concepts as follows: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."[5] The concept of sustainable development has been criticized in various ways. While some see it as paradoxical (or an oxymoron) and regard development as inherently unsustainable, others are disappointed in the lack of progress that has been achieved so far.[6][7] Part of the problem is that "development" itself is not consistently defined.[8]: 16

Definition

In 1987, the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development released the report Our Common Future, commonly called the Brundtland Report.[2] The report included a definition of "sustainable development" which is now widely used:[2]: Chapter 2

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains two key concepts within it:

- The concept of 'needs', in particular, the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

- The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs.

— World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (1987)

Sustainability

Development of the concept

Sustainable development has its roots in ideas about sustainable forest management, which were developed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries.[16][17]: 6–16 In response to a growing awareness of the depletion of timber resources in England, John Evelyn argued, in his 1662 essay Sylva, that "sowing and planting of trees had to be regarded as a national duty of every landowner, in order to stop the destructive over-exploitation of natural resources." In 1713, Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a senior mining administrator in the service of Elector Frederick Augustus I of Saxony published Sylvicultura economics, a 400-page work on forestry. Building upon the ideas of Evelyn and French minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, von Carlowitz developed the concept of managing forests for sustained yield.[16] His work influenced others, including Alexander von Humboldt and Georg Ludwig Hartig, eventually leading to the development of the science of forestry. This, in turn, influenced people like Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the US Forest Service, whose approach to forest management was driven by the idea of wise use of resources, and Aldo Leopold whose land ethic was influential in the development of the environmental movement in the 1960s.[16][17]

Following the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, the developing environmental movement drew attention to the relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation. Kenneth E. Boulding, in his influential 1966 essay The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth, identified the need for the economic system to fit itself to the ecological system with its limited pools of resources.[17] Another milestone was the 1968 article by Garrett Hardin that popularized the term "tragedy of the commons".[18] One of the first uses of the term sustainable in the contemporary sense was by the Club of Rome in 1972 in its classic report on the Limits to Growth, written by a group of scientists led by Dennis and Donella Meadows of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Describing the desirable "state of global equilibrium", the authors wrote: "We are searching for a model output that represents a world system that is sustainable without sudden and uncontrolled collapse and capable of satisfying the basic material requirements of all of its people."[19] That year also saw the publication of the influential A Blueprint for Survival book.[20][21]

In 1975, an MIT research group prepared ten days of hearings on "Growth and Its Implication for the Future" for the US Congress, the first hearings ever held on sustainable development.[22]

In 1980, the International Union for Conservation of Nature published a world conservation strategy that included one of the first references to sustainable development as a global priority[23] and introduced the term "sustainable development".[24]: 4 Two years later, the United Nations World Charter for Nature raised five principles of conservation by which human conduct affecting nature is to be guided and judged.[25]

Since the Brundtland Report, the concept of sustainable development has developed beyond the initial intergenerational framework to focus more on the goal of "socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth".[24]: 5 In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development published the Earth Charter, which outlines the building of a just, sustainable, and peaceful global society in the 21st century. The action plan Agenda 21 for sustainable development identified information, integration, and participation as key building blocks to help countries achieve development that recognizes these interdependent pillars. Furthermore, Agenda 21 emphasizes that broad public participation in decision-making is a fundamental prerequisite for achieving sustainable development.[26]

The Rio Protocol was a huge leap forward: for the first time, the world agreed on a sustainability agenda. In fact, a global consensus was facilitated by neglecting concrete goals and operational details. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) now have concrete targets (unlike the results from the Rio Process) but no methods for sanctions.[27][8]: 137

Dimensions

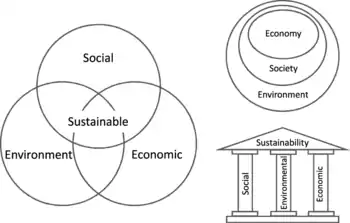

Sustainable development, like sustainability, is regarded to have three dimensions (also called pillars, domains, aspects, spheres and globalized etc.): the environment, economy and society.

Critique

The concept of sustainable development has been and still is, subject to criticism, including the question of what is to be sustained in sustainable development. It has been argued that there is no such thing as sustainable use of a non-renewable resource, since any positive rate of exploitation will eventually lead to the exhaustion of earth's finite stock;[31]: 13 this perspective renders the Industrial Revolution as a whole unsustainable.[32]: 20f [33]: 61–67 [34]: 22f

The sustainable development debate is based on the assumption that societies need to manage three types of capital (economic, social, and natural), which may be non-substitutable and whose consumption might be irreversible.[35] Natural capital can not necessarily be substituted by economic capital.[34] While it is possible that we can find ways to replace some natural resources, it is much less likely that they will ever be able to replace ecosystem services, such as the protection provided by the ozone layer, or the climate stabilizing function of the Amazonian forest.

The concept of sustainable development has been criticized from different angles. While some see it as paradoxical (or an oxymoron) and regard development as inherently unsustainable, others are disappointed in the lack of progress that has been achieved so far.[6][7] Part of the problem is that "development" itself is not consistently defined.[8]: 16

The vagueness of the Brundtland definition of sustainable development has been criticized as follows:[8]: 17 The definition has "opened up the possibility of downplaying sustainability. Hence, governments spread the message that we can have it all at the same time, i.e. economic growth, prospering societies and a healthy environment. No new ethic is required. This so-called weak version of sustainability is popular among governments, and businesses, but profoundly wrong and not even weak, as there is no alternative to preserving the earth’s ecological integrity."[36]: 2

Pathways

Requirements

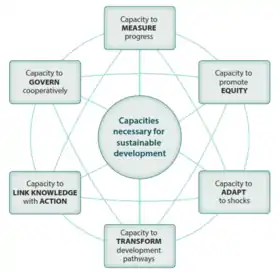

Six interdependent capacities are deemed to be necessary for the successful pursuit of sustainable development.[1] These are the capacities to measure progress towards sustainable development; promote equity within and between generations; adapt to shocks and surprises; transform the system onto more sustainable development pathways; link knowledge with action for sustainability; and to devise governance arrangements that allow people to work together

Environmental Characteristics of Sustainable Cities

A sustainable city is an urban center that improves its environmental impact through urban planning and management. For the definition of an eco-city, imagine a city with parks and green spaces, solar-powered buildings, rooftop gardens, and more pedestrians and bicycles than cars. This is not a futuristic dream. Smart cities are actively moving towards greener urban ecosystems and better environmental management. [37]

Environmental sustainability concerns the natural environment and how it endures and remains diverse and productive. Since natural resources are derived from the environment, the state of air, water, and climate is of particular concern. Environmental sustainability requires society to design activities to meet human needs while preserving the life support systems of the planet. This, for example, entails using water sustainably, using renewable energy and sustainable material supplies (e.g. harvesting wood from forests at a rate that maintains the biomass and biodiversity).[38]

An unsustainable situation occurs when natural capital (the total of nature's resources) is used up faster than it can be replenished.[39]: 58 Sustainability requires that human activity only uses nature's resources at a rate at which they can be replenished naturally. The concept of sustainable development is intertwined with the concept of carrying capacity. Theoretically, the long-term result of environmental degradation is the inability to sustain human life.[39]

Important operational principles of sustainable development were published by Herman Daly in 1990: renewable resources should provide a sustainable yield (the rate of harvest should not exceed the rate of regeneration); for non-renewable resources there should be equivalent development of renewable substitutes; waste generation should not exceed the assimilative capacity of the environment.[40]

| Consumption of natural resources | State of the environment | State of sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| More than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental degradation | Not sustainable |

| Equal to nature's ability to replenish | Environmental equilibrium | Steady state economy |

| Less than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental renewal | Environmentally sustainable |

Land use changes, agriculture and food

Environmental problems associated with industrial agriculture and agribusiness are now being addressed through approaches such as sustainable agriculture, organic farming and more sustainable business practices.[41] The most cost-effective climate change mitigation options include afforestation, sustainable forest management, and reducing deforestation.[42] At the local level there are various movements working towards sustainable food systems which may include less meat consumption, local food production, slow food, sustainable gardening, and organic gardening.[43] The environmental effects of different dietary patterns depend on many factors, including the proportion of animal and plant foods consumed and the method of food production.[44][45]

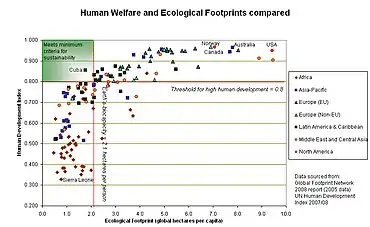

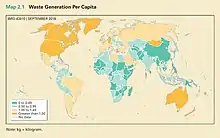

Materials and waste

As global population and affluence have increased, so has the use of various materials increased in volume, diversity, and distance transported. Included here are raw materials, minerals, synthetic chemicals (including hazardous substances), manufactured products, food, living organisms, and waste.[46] By 2050, humanity could consume an estimated 140 billion tons of minerals, ores, fossil fuels and biomass per year (three times its current amount) unless the economic growth rate is decoupled from the rate of natural resource consumption. Developed countries' citizens consume an average of 16 tons of those four key resources per capita per year, ranging up to 40 or more tons per person in some developed countries with resource consumption levels far beyond what is likely sustainable. By comparison, the average person in India today consumes four tons per year.[47]

Sustainable use of materials has targeted the idea of dematerialization, converting the linear path of materials (extraction, use, disposal in landfill) to a circular material flow that reuses materials as much as possible, much like the cycling and reuse of waste in nature.[48] Dematerialization is being encouraged through the ideas of industrial ecology, eco design[49] and ecolabelling.

This way of thinking is expressed in the concept of circular economy, which employs reuse, sharing, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing and recycling to create a closed-loop system, minimizing the use of resource inputs and the creation of waste, pollution and carbon emissions.[50] Building electric vehicles has been one of the most popular ways in the field of sustainable development, the potential of using reusable energy and reducing waste offered a perspective in sustainable development.[51] The European Commission has adopted an ambitious Circular Economy Action Plan in 2020, which aims at making sustainable products the norm in the EU.[52][53]

Biodiversity and ecosystem services

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. It recommended that human civilization will need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management.[54][55]

The 2022 IPCC report emphasizes how there have been many studies done on the loss of biodiversity, and provides additional strategies to decrease the rate of our declining biodiversity. The report suggests how preserving natural ecosystems, fire and soil management, and reducing the competition for land can create positive impacts on our environment, and contribute to sustainable development.[56]

Management of human consumption and impacts

The environmental impact of a community or humankind as a whole depends both on population and impact per person, which in turn depends in complex ways on what resources are being used, whether or not those resources are renewable, and the scale of the human activity relative to the carrying capacity of the ecosystems involved.[57] Careful resource management can be applied at many scales, from economic sectors like agriculture, manufacturing and industry, to work organizations, the consumption patterns of households and individuals, and the resource demands of individual goods and services.[58][59]

The underlying driver of direct human impacts on the environment is human consumption.[60] This impact is reduced by not only consuming less but also making the full cycle of production, use, and disposal more sustainable. Consumption of goods and services can be analyzed and managed at all scales through the chain of consumption, starting with the effects of individual lifestyle choices and spending patterns, through to the resource demands of specific goods and services, the impacts of economic sectors, through national economies to the global economy.[61] Key resource categories relating to human needs are food, energy, raw materials and water.

Improving on economic and social aspects

It has been suggested that because of rural poverty and overexploitation, environmental resources should be treated as important economic assets, called natural capital.[62] Economic development has traditionally required a growth in the gross domestic product. This model of unlimited personal and GDP growth may be over. Sustainable development may involve improvements in the quality of life for many but may necessitate a decrease in resource consumption.[63] "Growth" generally ignores the direct effect that the environment may have on social welfare, whereas "development" takes it into account.[64]

As early as the 1970s, the concept of sustainability was used to describe an economy "in equilibrium with basic ecological support systems".[65] Scientists in many fields have highlighted The Limits to Growth,[66][67] and economists have presented alternatives, for example a 'steady-state economy', to address concerns over the impacts of expanding human development on the planet.[34] In 1987, the economist Edward Barbier published the study The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development, where he recognized that goals of environmental conservation and economic development are not conflicting and can be reinforcing each other.[68]

A World Bank study from 1999 concluded that based on the theory of genuine savings (defined as "traditional net savings less the value of resource depletion and environmental degradation plus the value of investment in human capital"), policymakers have many possible interventions to increase sustainability, in macroeconomics or purely environmental.[69] Several studies have noted that efficient policies for renewable energy and pollution are compatible with increasing human welfare, eventually reaching a golden-rule steady state.[70][71][72][73]

A meta review in 2002 looked at environmental and economic valuations and found a "lack of concrete understanding of what “sustainability policies” might entail in practice".[74] A study concluded in 2007 that knowledge, manufactured and human capital (health and education) has not compensated for the degradation of natural capital in many parts of the world.[75] It has been suggested that intergenerational equity can be incorporated into a sustainable development and decision making, as has become common in economic valuations of climate economics.[76]

The 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report discussed how ambitious climate change mitigation policies have created negative social and economical impacts when they are not aligned with sustainable development goals. As a result, the transition towards sustainable development mitigation policies has slowed down which is why the inclusivity and considerations of justice of these policies may weaken or support improvements on certain regions as there are other limiting factors such as poverty, food insecurity, and water scarcity that may impede the governments application of policies that aim to build a low carbon future.[77]

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development published a Vision 2050 document in 2021 to show "How business can lead the transformations the world needs". The vision states that "we envision a world in which 9+billion people can live well, within planetary boundaries, by 2050."[78] This report was highlighted by The Guardian as "the largest concerted corporate sustainability action plan to date – include reversing the damage done to ecosystems, addressing rising greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring societies move to sustainable agriculture."[79]

Gender and leadership in sustainable development

Gender and sustainable development have been examined, focusing on women's leadership potential and barriers to it. While leadership roles in sustainable development have become more androgynous over time, patriarchal structures and perceptions continue to constrain women from becoming leaders.[80] Some hidden issues are women's lack of self-confidence, impeding access to leadership roles, but men can potentially play a role as allies for women's leadership.[81]

Barriers

There are barriers that small and medium enterprises face when implementing sustainable development such as lack of expertise, lack of resources, and high initial capital cost of implementing sustainability measures.[82]

Globally, the lack of political will is a barrier to achieving sustainable development.[83] To overcome this impediment, governments must jointly form an agreement of social and political strength. Efforts to enact reforms or design and implement programs to decrease the harmful effects of human behaviors allow for progress toward present and future environmental sustainability goals.[84] The Paris Agreement exemplifies efforts of political will on a global level, a multinational agreement between 193 parties [85] intended to strengthen the global response to climate change by reducing emissions and working together to adjust to the consequent effects of climate change.[85] Experts continue to firmly suggest that governments should do more outside of The Paris Agreement, there persist a greater need for political will.[86]

Another barrier towards sustainable development would be negative externalities that may potentially arise from implementing sustainable development technology. One example would be the development of lithium-ion batteries, a key element towards environmental sustainability and the reduction in reliance towards fossil fuels. However, currently with the technology and methodology available, Lithium production poses a negative environmental impact during its extraction from the earth as it uses a method very similar to fracking as well as during its processing to be used as a battery which is a chemically intensive process.[87] One suggested solution would be to weigh the possibility of recycling as this will cut down on the waste of old lithium as well as reducing the need for extracting new lithium from the ground, however, this sustainable development solution is barred from implementation by a high initial cost as studies have shown that recycling old technology for the purpose of extracting metals such as lithium and cobalt is typically more expensive than extracting them from the ground and processing them.[88]

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or Global Goals are a collection of 17 interlinked global goals designed to be a "shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future".[89][90] The SDGs were set up in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly (UN-GA) and are intended to be achieved by 2030. They are included in a UN-GA Resolution called the 2030 Agenda or what is colloquially known as Agenda 2030.[91] The SDGs were developed in the Post-2015 Development Agenda as the future global development framework to succeed the Millennium Development Goals which were ended in 2015. The SDGs emphasize the interconnected environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable development, by putting sustainability at their center.[92]

The 17 SDGs are: No poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, decent work and economic growth, industry, innovation and infrastructure, Reduced Inequality, Sustainable Cities and Communities, Responsible Consumption and Production, Climate Action, Life Below Water, Life On Land, Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, Partnerships for the Goals. Though the goals are broad and interdependent, two years later (6 July 2017), the SDGs were made more "actionable" by a UN Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. The resolution identifies specific targets for each goal, along with indicators that are being used to measure progress toward each target.[93] The year by which the target is meant to be achieved is usually between 2020 and 2030.[94] For some of the targets, no end date is given.

There are cross-cutting issues and synergies between the different goals. Cross-cutting issues include gender equality, education, culture and health. With regards to SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies, particularly for the SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans).[95][96]: 70 Synergies amongst the SDGs are "the good antagonists of trade-offs".[96]: 67 Some of the known and much discussed conceptual problem areas of the SDGs include: The fact that there are competing and too many goals (resulting in problems of trade-offs), that they are weak on environmental sustainability and that there are difficulties with tracking qualitative indicators. For example, these are two difficult trade-offs to consider: "How can ending hunger be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 2.3 and 15.2) How can economic growth be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 9.2 and 9.4) "[97]Education for sustainable development

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is a term used by the United Nations and is defined as education that encourages changes in knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to enable a more sustainable and just society for all. ESD aims to empower and equip current and future generations to meet their needs using a balanced and integrated approach to the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development.[98]

Agenda 21 was the first international document that identified education as an essential tool for achieving sustainable development and highlighted areas of action for education.[99][100] ESD is a component of measurement in an indicator for Sustainable Development Goal 12 (SDG) for "responsible consumption and production". SDG 12 has 11 targets and target 12.8 is "By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature."[101] 20 years after the Agenda 21 document was declared, the ‘Future we want’ document was declared in the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development, stating that "We resolve to promote education for sustainable development and to integrate sustainable development more actively into education beyond the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development."[102]

One version of education for Sustainable Development recognizes modern-day environmental challenges and seeks to define new ways to adjust to a changing biosphere, as well as engage individuals to address societal issues that come with them [103] In the International Encyclopedia of Education, this approach to education is seen as an attempt to "shift consciousness toward an ethics of life-giving relationships that respects the interconnectedness of man to his natural world" in order to equip future members of society with environmental awareness and a sense of responsibility to sustainability.[104]

For UNESCO, education for sustainable development involves:

integrating key sustainable development issues into teaching and learning. This may include, for example, instruction about climate change, disaster risk reduction, biodiversity, and poverty reduction and sustainable consumption. It also requires participatory teaching and learning methods that motivate and empower learners to change their behaviours and take action for sustainable development. ESD consequently promotes competencies like critical thinking, imagining future scenarios and making decisions in a collaborative way.[105][106]

The Thessaloniki Declaration, presented at the "International Conference on Environment and Society: Education and Public Awareness for Sustainability" by UNESCO and the Government of Greece (December 1997), highlights the importance of sustainability not only with regards to the natural environment, but also with "poverty, health, food security, democracy, human rights, and peace".[107]

See also

- Climate change education (CCE)

- Environmental education

- Global citizenship education

- Human population planning

- List of sustainability topics

- Outline of sustainability

- United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development

References

- Clark, William; Harley, Alicia (2020). "Sustainability Science: Toward a Synthesis". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 331–86. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-043621.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - United Nations General Assembly (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment.

- United Nations General Assembly (20 March 1987). "Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development; Paragraph 1". United Nations General Assembly. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Purvis, Ben; Mao, Yong; Robinson, Darren (2019). "Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins". Sustainability Science. 14 (3): 681–695. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5. ISSN 1862-4065.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - "Sustainable Development". UNESCO. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Brown, James H. (1 October 2015). "The Oxymoron of Sustainable Development". BioScience. 65 (10): 1027–1029. doi:10.1093/biosci/biv117.

- Williams, Colin C; Millington, Andrew C (June 2004). "The diverse and contested meanings of sustainable development". The Geographical Journal. 170 (2): 99–104. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.00111.x. S2CID 143181802.

- Berg, Christian (2020). Sustainable action : overcoming the barriers. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-0-429-57873-1. OCLC 1124780147.

- Purvis, Ben; Mao, Yong; Robinson, Darren (2019). "Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins". Sustainability Science. 14 (3): 681–695. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5. ISSN 1862-4065.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - Ramsey, Jeffry L. (2015). "On Not Defining Sustainability". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 28 (6): 1075–1087. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3. ISSN 1187-7863. S2CID 146790960.

- Berg, Christian (2020). Sustainable action : overcoming the barriers. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-0-429-57873-1. OCLC 1124780147.

- Kotzé, Louis J.; Kim, Rakhyun E.; Burdon, Peter; du Toit, Louise; Glass, Lisa-Maria; Kashwan, Prakash; Liverman, Diana; Montesano, Francesco S.; Rantala, Salla (2022), Sénit, Carole-Anne; Biermann, Frank; Hickmann, Thomas (eds.), "Planetary Integrity", The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals?, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 140–171, doi:10.1017/9781009082945.007, ISBN 978-1-316-51429-0

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - Bosselmann, Klaus (2010). "Losing the Forest for the Trees: Environmental Reductionism in the Law". Sustainability. 2 (8): 2424–2448. doi:10.3390/su2082424. ISSN 2071-1050.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - UNEP (2021). "Making Peace With Nature". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Steffen, Will; Rockström, Johan; Cornell, Sarah; Fetzer, Ingo; Biggs, Oonsie; Folke, Carl; Reyers, Belinda. "Planetary Boundaries - an update". Stockholm Resilience Centre. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Ulrich Grober: Deep roots — A conceptual history of "sustainable development" (Nachhaltigkeit), Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, 2007

- Blewitt, John (2015). Understanding Sustainable Development (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415707824. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Hardin, Garrett (13 December 1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–1248. Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 5699198.

- Finn, Donovan (2009). Our Uncertain Future: Can Good Planning Create Sustainable Communities?. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois.

- "A Blueprint for Survival". The New York Times. 5 February 1972. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "The Ecologist January 1972: a blueprint for survival". The Ecologist. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Growth and its implications for the future" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- World Conservation Strategy: Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 1980.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231173155.

- World Charter for Nature, United Nations, General Assembly, 48th Plenary Meeting, 28 October 1982

- Will Allen. 2007."Learning for Sustainability: Sustainable Development."

- "Why Rio failed in the past and how it can succeed this time". The Guardian. 12 June 2012.

- Obrecht, Andreas; Pham-Truffert, Myriam; Spehn, Eva; Payne, Davnah; Altermatt, Florian; Fischer, Manuel; Passarello, Cristian; Moersberger, Hannah; Schelske, Oliver; Guntern, Jodok; Prescott, Graham (5 February 2021). "Achieving the SDGs with Biodiversity". doi:10.5281/zenodo.4457298.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 16 September 2005, 60/1. 2005 World Summit Outcome" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Aachener Stiftung Kathy Beys, 2005-2022 (13 November 2015). "Lexikon der Nachhaltigkeit | Definitionen | Nachhaltigkeit Definition". Lexikon der Nachhaltigkeit (in German). Retrieved 19 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Turner, R. Kerry (1988). "Sustainability, Resource Conservation and Pollution Control: An Overview". In Turner, R. Kerry (ed.). Sustainable Environmental Management. London: Belhaven Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Full book accessible at Scribd). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674257801.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (1980). Entropy: A New World View (PDF contains only the title and contents pages of the book). New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670297177.

- Daly, Herman E. (1992). Steady-state economics (2nd ed.). London: Earthscan Publications.

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. (2002). "Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability". Business Strategy and the Environment. 11 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1002/bse.323.

- Bosselmann, Klaus (2017). The principle of sustainability : transforming law and governance (2nd ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-4724-8128-3. OCLC 951915998.

- https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/11-sustainable-cities-and-communities/

- "Sustainable development domains". Semantic portal. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Nayeripour, Majid; Kheshti, Mostafa (2 December 2011). Sustainable Growth and Applications in Renewable Energy Sources. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-953-307-408-5.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - Daly, H.E. (1990). "Toward some operational principles of sustainable development". Ecological Economics. 2 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(90)90010-r.

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development Archived 10 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine This web site has multiple articles on WBCSD contributions to sustainable development. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- "AR5 Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change — IPCC". Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Holmgren, D. (March 2005). "Retrofitting the suburbs for sustainability." Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine CSIRO Sustainability Network. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- McMichael A.J.; Powles J.W.; Butler C.D.; Uauy R. (September 2007). "Food, Livestock Production, Energy, Climate change, and Health" (PDF). Lancet. 370 (9594): 1253–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61256-2. hdl:1885/38056. PMID 17868818. S2CID 9316230. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Baroni L.; Cenci L.; Tettamanti M.; Berati M. (February 2007). "Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Various Dietary Patterns Combined with Different Food Production Systems" (PDF). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61 (2): 279–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602522. PMID 17035955. S2CID 16387344. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Bournay, E. et al.. (2006). Vital waste graphics 2. The Basel Convention, UNEP, GRID-Arendal. ISBN 82-7701-042-7.

- UNEP (2011). Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth. ISBN 978-92-807-3167-5. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Anderberg, S (1998). "Industrial metabolism and linkages between economics, ethics, and the environment". Ecological Economics. 24 (2–3): 311–320. doi:10.1016/s0921-8009(97)00151-1.

- Fuad-Luke, A. (2006). The Eco-design Handbook. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28521-3.

- Geissdoerfer, Martin; Savaget, Paulo; Bocken, Nancy M. P.; Hultink, Erik Jan (1 February 2017). "The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 143: 757–768. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048. S2CID 157449142.

- Shigeta, N., & Hosseini, S. E. (2020). Sustainable Development of the Automobile Industry in the United States, Europe, and Japan with Special Focus on the Vehicles’ Power Sources. Energies, 14(1), 78. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/en14010078

- European Commission (2020). Circular economy action plan. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- "EUR-Lex - 52020DC0098 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (PDF). the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 6 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Deutsche Welle, Deutsche (6 May 2019). "Why Biodiversity Loss Hurts Humans as Much as Climate Change Does". Ecowatch. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change". www.ipcc.ch. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Basiago, Andrew D. (1995). "Methods of defining 'sustainability'". Sustainable Development. 3 (3): 109–119. doi:10.1002/sd.3460030302. ISSN 0968-0802.

- Clark, D. (2006). A Rough Guide to Ethical Living. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-84353-792-2

- Brower, M. & Leon, W. (1999). The Consumer's Guide to Effective Environmental Choices: Practical Advice from the Union of Concerned Scientists. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80281-X.

- Michaelis, L. & Lorek, S. (2004). "Consumption and the Environment in Europe: Trends and Futures." Danish Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Project No. 904.

- Jackson, T. & Michaelis, L. (2003). "Policies for Sustainable Consumption". The UK Sustainable Development Commission.

- Barbier, Edward B. (2006). Natural Resources and Economic Development. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780521706513. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Brown, L. R. (2011). World on the Edge. Earth Policy Institute. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08029-2.

- Pezzey, John (November 1992). "Sustainable development concepts" (PDF). Researchgate. The World Bank. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- Stivers, R. 1976. The Sustainable Society: Ethics and Economic Growth. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W.W. Behrens III. 1972. The Limits to Growth. Universe Books, New York, NY. ISBN 0-87663-165-0

- Meadows, D.H.; Randers, Jørgen; Meadows, D.L. (2004). Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1-931498-58-6.

- Barbier, E. (1987). "The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development". Environmental Conservation. 14 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1017/S0376892900011449. S2CID 145595791.

- Hamilton, K.; Clemens, M. (1999). "Genuine savings rates in developing countries". World Bank Economic Review. 13 (2): 333–356. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.7532. doi:10.1093/wber/13.2.333.

- Ayong Le Kama, A. D. (2001). "Sustainable growth renewable resources, and pollution". Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 25 (12): 1911–1918. doi:10.1016/S0165-1889(00)00007-5.

- Chichilnisky, G.; Heal, G.; Beltratti, A. (1995). "A Green Golden Rule". Economics Letters. 49 (2): 175–179. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(95)00662-Y. S2CID 154964259.

- Endress, L.; Roumasset, J. (1994). "Golden rules for sustainable resource management" (PDF). Economic Record. 70 (210): 266–277. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.1994.tb01847.x.

- Endress, L.; Roumasset, J.; Zhou, T. (2005). "Sustainable Growth with Environmental Spillovers". Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 58 (4): 527–547. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.529.5305. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.09.003.

- Pezzey, John C. V.; Michael A., Toman (2002). "The Economics of Sustainability: A Review of Journal Articles" (PDF). —. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Dasgupta, P. (2007). "The idea of sustainable development". Sustainability Science. 2 (1): 5–11. doi:10.1007/s11625-007-0024-y. S2CID 154597956.

- Heal, G. (2009). "Climate Economics: A Meta-Review and Some Suggestions for Future Research". Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 3 (1): 4–21. doi:10.1093/reep/ren014. S2CID 154917782.

- New, M., D. Reckien, D. Viner, C. Adler, S.-M. Cheong, C. Conde, A. Constable, E. Coughlan de Perez, A. Lammel, R. Mechler, B. Orlove, and W. Solecki, 2022: Decision Making Options for Managing Risk. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

- "Vision 2050 - Time to transform". WBCSD. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Wills, Jackie (15 May 2014). "World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Vision 2050". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Shinbrot, Xoco A., Kate Wilkins, Ulrike Gretzel, Gillian Bowser. "Unlocking women’s sustainability leadership potential: Perceptions of contributions and challenges for women in sustainable development." World Development 119 (2019): 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.009

- Shinbrot, Xoco A., Kate Wilkins, Ulrike Gretzel, Gillian Bowser. "Unlocking women’s sustainability leadership potential: Perceptions of contributions and challenges for women in sustainable development." World Development 119 (2019): 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.009

- Sossa, Jhon. "Barriers to sustainability for small and medium enterprises in the framework of sustainable development—Literature review". onlinelibrary.wiley.com. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- https://hdl.handle.net/2134/23679

- https://ccsi.columbia.edu/news/political-will-what-it-why-it-matters-extractives-and-how-earth-do-you-find-it

- https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement

- https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements#chapter-title-0-7

- https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2020.1754596

- https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=155244371&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- "THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development". sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- Schleicher, Judith; Schaafsma, Marije; Vira, Bhaskar (2018). "Will the Sustainable Development Goals address the links between poverty and the natural environment?". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 34: 43–47. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.09.004.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- "SDG Indicators - Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development". United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "The SDG Report 2020". UN Stats Open SDGs Data Hub. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Berg, Christian (2020). Sustainable action : overcoming the barriers. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-0-429-57873-1. OCLC 1124780147.

- Machingura, Fortunate (27 February 2017). "The Sustainable Development Goals and their trade-offs". ODI: Think change. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Issues and trends in education for sustainable development. Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 7. ISBN 978-92-3-100244-1.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Leicht, Alexander (2018). "From Agenda 21 to Target 4.7: the development of education for sustainable development". UNESCO, UNESDOC Digital Library. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Bernad-Cavero, Olga; Llevot-Calvet, Núria (4 July 2018). New Pedagogical Challenges in the 21st Century: Contributions of Research in Education. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-1-78923-380-3.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- Shulla, K.; Leal Filho, W.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J. H.; Borgemeister, C. (6 February 2020). "Sustainable development education in the context of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development". Taylor & Francis Online. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Schooling for sustainable development in Europe : concepts, policies and educational experiences at the end of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Jucker, Rolf, 1963-, Mathar, Reiner. Cham [Switzerland]. 27 October 2014. ISBN 978-3-319-09549-3. OCLC 894509040.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - International encyclopedia of education. Peterson, Penelope L.,, Baker, Eva L.,, McGaw, Barry (3rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. 2010. ISBN 978-0-08-044894-7. OCLC 645208716.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Education for Sustainable Development". UNESCO. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Marope, P.T.M; Chakroun, B.; Holmes, K.P. (2015). Unleashing the Potential: Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training (PDF). UNESCO. pp. 9, 23, 25–26. ISBN 978-92-3-100091-1.

- Nikolopoulou, Anastasia; Abraham, Taisha; Mirbagheri, Farid (2010). Education for Sustainable Development: Challenges, Strategies, and Practices in a Globalizing World Education for sustainable development: Challenges, strategies, and practices in a globalizing world. doi:10.4135/9788132108023. ISBN 9788132102939.