Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,[1] anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian[2][3] political philosophy within the socialist movement which rejects the state's control of the economy under state socialism.[4] Overlapping with anarchism and libertarianism,[5][6] libertarian socialists criticize wage slavery relationships within the workplace,[7] emphasizing workers' self-management[8] and decentralized structures of political organization.[9][10][11] As a broad socialist tradition and movement, libertarian socialism includes anarchist, Marxist, and anarchist- or Marxist-inspired thought and other left-libertarian tendencies.[12] Anarchism and libertarian Marxism are the main currents of libertarian socialism.[13][14]

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

|

Libertarian socialism rejects the concept of a state.[8] It asserts that a society based on freedom and justice can only be achieved with the abolition of authoritarian institutions that control specific means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[15] Libertarian socialists advocate for decentralized structures based on direct democracy and federal or confederal associations[16] such as citizens'/popular assemblies, cooperatives, libertarian municipalism, trade unions and workers' councils.[17][18] This is done within a general call for liberty[19] and free association[20] through the identification, criticism and practical dismantling of illegitimate authority in all aspects of human life.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] Libertarian socialism is distinguished from the authoritarian and vanguardist approach of Bolshevism/Leninism and the reformism of Fabianism/social democracy.[29][30]

A form and socialist wing of left-libertarianism,[31][3][32] past and present currents and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism (especially anarchist schools of thought such as anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism,[33] collectivist anarchism, green anarchism, individualist anarchism,[34][35][36][37] mutualism,[38] and social anarchism) as well as communalism, some forms of democratic socialism, guild socialism,[39] libertarian Marxism[40] (autonomism, council communism,[41] left communism among others),[42][43] participism, revolutionary syndicalism, and some versions of utopian socialism.[44]

Overview

Name

Libertarian socialism is also referred to as socialist libertarianism[31] and often used interchangeably with the terms anarcho-socialism,[45][46] anarchist socialism,[47] free socialism.[48] stateless socialism,[49] and socialist anarchism.[50]

Definition

Libertarian socialism is a Western philosophy with diverse interpretations, although some general commonalities can be found in its many incarnations. It advocates a worker-oriented system of production and organization in the workplace that, in some aspects, radically departs from neoclassical economics in favour of democratic cooperatives or common ownership of the means of production (socialism).[51] They propose that this economic system be executed in a manner that attempts to maximize the liberty of individuals and minimize the concentration of power or authority (libertarianism). Adherents propose achieving this through decentralization of political and economic power, usually involving the socialization of most large-scale private property and enterprise (while retaining respect for personal property). Libertarian socialism tends to deny the legitimacy of most forms of economically significant private property, viewing capitalist property relations as a form of domination that is antagonistic to individual freedom.[52]

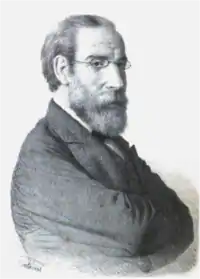

The first anarchist journal to use the term libertarian was Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social, and it was published in New York City between 1858 and 1861 by French libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque.[53] The next recorded use of the term was in Europe when libertarian communism was used at a French regional anarchist Congress at Le Havre (16–22 November 1880). January 1881 saw a French manifesto on "Libertarian or Anarchist Communism". Finally, 1895 saw leading anarchists Sébastien Faure and Louise Michel publish Le Libertaire in France.[53] The term stems from the French cognate libertaire used to evade the French ban on anarchist publications.[54] In this tradition, libertarianism is generally used as a synonym for anarchism, the term's original meaning.[55] In the context of the European socialist movement, the term libertarian has been conventionally used to describe socialists who opposed authoritarianism and state socialism, such as Mikhail Bakunin and largely overlaps with social anarchism.[56][57] However, individualist anarchism is also libertarian socialist.[58] Non-Lockean individualism encompasses socialism, including libertarian socialism.[59]

The association of socialism with libertarianism predates that of capitalism, and many anti-authoritarians still decry what they see as a mistaken association of capitalism with libertarianism in the United States.[60] As Noam Chomsky put it, a consistent libertarian "must oppose private ownership of the means of production and wage slavery, which is a component of this system, as incompatible with the principle that labor must be freely undertaken and under the control of the producer".[61] Terms such as anarchist socialism, anarcho-socialism, free socialism, stateless socialism, socialist anarchism and socialist libertarianism have all been used to refer to the anarchist wing of libertarian socialism[31] or vis-à-vis authoritarian forms of socialism.[62][63]

In a chapter of his Economic Justice and Democracy (2005) recounting the history of libertarian socialism, economist Robin Hahnel relates that the period where libertarian socialism had its most significant impact was at the end of the 19th century through the first four decades of the 20th century. According to Hahnel, "libertarian socialism was as powerful a force as social democracy and communism" in the early 20th century. The Anarchist St. Imier International, referred by Hahnel as the Libertarian International, was founded at the 1872 Congress of St. Imier a few days after the split between Marxists and libertarians at The Hague Congress of the First International, referred to by Hahnel as the Socialist International. This Libertarian International "competed successfully against social democrats and communists alike for the loyalty of anticapitalist activists, revolutionaries, workers, unions and political parties for over fifty years". For Hahnel, libertarian socialists "played a major role in the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917. Libertarian socialists played a dominant role in the Mexican Revolution of 1911. Twenty years after World War I was over, libertarian socialists were still strong enough to spearhead the social revolution that swept across Republican Spain in 1936 and 1937".[64]

On the other hand, a libertarian trend also developed within Marxism which gained visibility around the late 1910s mainly in reaction against Bolshevism and Leninism rising to power and establishing the Soviet Union.[65][66][67] Libertarian socialists argue that these states were transitioning from capitalism to socialism following Leninist doctrine and never reached further stages of development.[68] Libertarian socialists seek the abolition of the state without going through a state capitalist transitionary stage.[69]

In his preface to Peter Kropotkin's book The Conquest of Bread, Kent Bromley considered French utopian socialist Charles Fourier to be the founder of the libertarian branch of socialist thought instead of the authoritarian socialist ideas of the French François-Noël Babeuf and the Italian Philippe Buonarroti.[44]

Anti-capitalism

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

|

According to John O'Neil, "[i]t is forgotten that the early defenders of commercial society like [Adam] Smith were as much concerned with criticising the associational blocks to mobile labour represented by guilds as they were to the activities of the state. The history of socialist thought includes a long associational and anti-statist tradition prior to the political victory of the Bolshevism in the east and varieties of Fabianism in the west".[70]

Libertarian socialism is anticapitalist and can be distinguished from capitalist and right-libertarian principles, which concentrate economic power in the hands of those who own the most capital. Libertarian socialism aims to distribute power more widely among members of society. Libertarian socialism and right-libertarian ideologies such as neoliberalism differ in that advocates of the former generally believe that one's degree of freedom is affected by one's economic and social status. In contrast, advocates of the latter believe in the freedom of choice within a capitalist framework, specifically under capitalist private property.[71] This is sometimes characterized as a desire to maximize free creativity in a society in preference to free enterprise.[72]

Within anarchism emerged a critique of wage slavery which refers to a situation perceived as quasi-voluntary slavery,[73] where a person's livelihood depends on wages, especially when the dependence is total and immediate.[74][75] It is a negatively connoted term used to draw an analogy between slavery and wage labour by focusing on similarities between owning and renting a person. The term "wage slavery" has been used to criticize economic exploitation and social stratification, with the former seen primarily as unequal bargaining power between labour and capital (particularly when workers are paid comparatively low wages, e.g. in sweatshops)[76] and the latter as a lack of workers' self-management, fulfilling job choices and leisure in an economy.[77][78][79] Libertarian socialists believe that by valuing freedom, society works towards a system in which individuals have the power to decide economic issues along with political issues. Libertarian socialists seek to replace unjustified authority with direct democracy, voluntary federation and popular autonomy in all aspects of life,[80] including physical communities and economic enterprises. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, thinkers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Karl Marx elaborated the comparison between wage labour and slavery in the context of a critique of societal property not intended for active personal use.[81][82] Luddites emphasized the dehumanization brought about by machines, while later, Emma Goldman famously denounced wage slavery by saying: "The only difference is that you are hired slaves instead of block slaves".[83]

Many libertarian socialists believe that large-scale voluntary associations should manage industrial production while workers retain rights to the individual products of their labour.[84] They see a distinction between concepts of private property and personal possession. Private property grants an individual exclusive control over a thing whether it is in use or not, and regardless of its productive capacity, possession grants no rights to things that are not in use.[85] Furthermore, "the separation of work and life is questioned and alternatives suggested that are underpinned by notions of dignity, self-realization and freedom from domination and exploitation. Here, a freedom that is not restrictively negative (as in neo-liberal conceptions) but is, as well, positive – connected, that is, to views about human flourishing – is important, a profoundly embedded understanding of freedom, which ties freedom to its social, communal conditions and, importantly, refuses to separate questions of freedom from those of equality".[86]

Anti-authoritarianism and opposition to the state

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

|

Libertarian philosophy generally regards concentrations of power as sources of oppression that must be continually challenged and justified. Most libertarian socialists believe that when power is exercised as exemplified by the economic, social, or physical dominance of one individual over another, the burden of proof is always on the authoritarian to justify their action as legitimate when taken against its effect of narrowing the scope of human freedom.[87] Libertarian socialists oppose rigid and stratified authority structures, whether political, economic, or social.[88]

Instead of corporations and states, libertarian socialists seek to organize society into voluntary associations (usually collectives, communes, municipalities, cooperatives, commons, or syndicates) that use direct democracy or consensus for their decision-making process. Some libertarian socialists advocate combining these institutions using rotating, recallable delegates to higher-level federations.[89] Spanish anarchism is a significant example of such federations in practice.

Contemporary examples of libertarian socialist organizational and decision-making models in practice include many anticapitalist and global justice movements,[90] including Zapatista Councils of Good Government and the global Indymedia network (which covers 45 countries on six continents). There are also many examples of indigenous societies worldwide whose political and economic systems can be accurately described as anarchist or libertarian socialist, each uniquely suited to the culture that birthed it.[91] For libertarians, that diversity of practice within a framework of common principles is proof of the vitality of those principles and their flexibility and strength.

Contrary to popular opinion, libertarian socialism has not traditionally been a utopian movement, tending to avoid dense theoretical analysis or prediction of what a future society would or should look like. The tradition instead has been that such decisions cannot be made now and must be made through struggle and experimentation so that the best solution can be arrived at democratically and organically and to base the direction for struggle on established historical examples. They point out that the success of the scientific method comes from its adherence to open rational exploration, not its conclusions, in sharp contrast to dogma and predetermined predictions. Noted anarchist Rudolf Rocker once stated: "I am an anarchist not because I believe anarchism is the final goal, but because there is no such thing as a final goal".[92]

Because libertarian socialism encourages exploration and embraces a diversity of ideas rather than forming a compact movement, there have arisen inevitable controversies over individuals who describe themselves as libertarian socialists yet disagree with some of the core principles of libertarian socialism. Peter Hain interprets libertarian socialism as minarchist rather than anarchist, favouring radical decentralization of power without going as far as the complete abolition of the state.[93] Libertarian socialist Noam Chomsky supports dismantling all forms of unjustified social or economic power while emphasizing that state intervention should be supported as temporary protection while oppressive structures remain in existence.[94] Similarly, Peter Marshall includes "the decentralist who wishes to limit and devolve State power, to the syndicalist who wants to abolish it altogether. It can even encompass the Fabians and the social democrats who wish to socialize the economy but who still see a limited role for the State".[12]

Proponents are known for opposing the existence of states or governments and refusing to participate in coercive state institutions. In the past, many refused to swear oaths in court or to participate in trials, even when they faced imprisonment[95] or deportation.[96] For Chamsy el-Ojeili, "it is frequently to forms of working-class or popular self-organization that Left communists look in answer to the questions of the struggle for socialism, revolution and post-capitalist social organization. Nevertheless, Left communists have often continued to organize themselves into party-like structures that undertake agitation, propaganda, education and other forms of political intervention. This is a vexed issue across Left communism and has resulted in a number of significant variations – from the absolute rejection of separate parties in favour of mere study or affinity groups, to the critique of the naivety of pure spontaneism and an insistence on the necessary, though often modest, role of disciplined, self-critical and popularly connected communist organizations".[97]

Civil liberties and individual freedom

Libertarian socialists have been strong advocates and activists of civil liberties (including freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, and other civil liberties[98]) that provide individual specific rights such as the freedom in issues of love and sex (free love) and of thought and conscience (freethought). In this activism, they have clashed with state and religious institutions which have limited such rights. Anarchism has been an important advocate of free love since its birth. A strong tendency for free love later appeared alongside anarcha-feminism and advocacy of LGBT rights. Recently, anarchism has voiced opinions and taken action around certain sex-related subjects such as pornography,[99] BDSM[100] and the sex industry.[100]

Anarcha-feminism developed as a synthesis of radical feminism and anarchism that views patriarchy (male domination over women) as a fundamental manifestation of compulsory government. It was inspired by the late 19th-century writings of early feminist anarchists such as Lucy Parsons, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and Virginia Bolten. Like other radical feminists, anarcha-feminists criticise and advocate the abolition of traditional conceptions of family, education and gender roles. Council communist Sylvia Pankhurst was also a feminist activist as well as a libertarian Marxist. Anarchists also took a pioneering interest in issues related to LGBTI persons. An important current within anarchism is free love.[101] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to the early anarchist Josiah Warren and experimental communities, who viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[101]

Libertarian socialists have traditionally been sceptical of and opposed to organized religion.[102] Freethought is a philosophical viewpoint that holds opinions should be formed based on science, logic and reason; and should not be influenced by authority, tradition, or other dogmas.[103][104] The cognitive application of freethought is known as freethinking, and practitioners of freethought are known as freethinkers.[103] In the United States, freethought was an anti-Christian and anti-clerical movement "whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters". Some contributors to the anarchist journal Liberty were prominent figures in both anarchism and freethought. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was co-editor of Freethought and The Truth Seeker. E. C. Walker was also co-editor of Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, another free love and freethought journal.[105] Free Society (1895–1897 as The Firebrand; 1897–1904 as Free Society) was a major anarchist newspaper in the United States at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.[106] The publication staunchly advocated free love and women's rights and critiqued comstockery—censorship of sexual information. In 1901, Catalan anarchist and freethinker Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia established modern or progressive schools in Barcelona in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church.[107] The schools' goal was to "educate the working class in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting". Fiercely anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", education free from the authority of church and state.[108]

Later in the 20th century, Austrian Freudo-Marxist Wilhelm Reich, who coined the phrase sexual revolution in one of his books from the 1940s,[109] became a consistent propagandist for sexual freedom, going as far as opening free sex counseling clinics in Vienna for working-class patients (Sex-Pol stood for the German Society of Proletarian Sexual Politics). According to Elizabeth Danto, Reich offered a mixture of "psychoanalytic counseling, Marxist advice and contraceptives" and "argued for sexual expressiveness for all, including the young and the unmarried, with a permissiveness that unsettled both the political left and the psychoanalysts". The clinics were immediately overcrowded by people seeking help.[110] During the early 1970s, the English anarchist and pacifist Alex Comfort achieved international celebrity for writing the sex manuals The Joy of Sex[111] and More Joy of Sex.[112]

Violent and nonviolent means

Some libertarian socialists see violent revolution as necessary to abolish capitalist society, while others advocate nonviolent methods. Along with many others, Errico Malatesta argued that the use of violence was necessary. As he put it in Umanità Nova (no. 125, September 6, 1921):

It is our aspiration and our aim that everyone should become socially conscious and effective; but to achieve this end, it is necessary to provide all with the means of life and for development, and it is therefore necessary to destroy with violence, since one cannot do otherwise, the violence that denies these means to the workers.[113]

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued in favour of a nonviolent revolution through a process of dual power in which libertarian socialist institutions would be established and form associations enabling the formation of an expanding network within the existing state capitalist framework to eventually render both the state and the capitalist economy obsolete. The progression towards violence in anarchism stemmed partly from the massacres of some of the communes inspired by the ideas of Proudhon and others. Many anarcho-communists began to see a need for revolutionary violence to counteract the violence inherent in capitalism and government.[114]

Anarcho-pacifism is a tendency within the anarchist movement which rejects the use of violence in the struggle for social change.[115][116] The main early influences were the thought of Henry David Thoreau[116] and Leo Tolstoy.[115][116] It developed "mostly in Holland [sic], Britain, and the United States, before and during the Second World War".[117] Opposition to the use of violence has not prohibited anarcho-pacifists from accepting the principle of resistance or even revolutionary action, provided it does not result in violence; it was, in fact, their approval of such forms of opposition to power that led many anarcho-pacifists to endorse the anarcho-syndicalist concept of the general strike as the great revolutionary weapon. Anarcho-pacifists have also come to endorse the nonviolent strategy of dual power.

Other anarchists have believed that violence (especially self-defence) is justified as a way to provoke social upheaval that could lead to a social revolution.

Environmental issues

| Part of a series on |

| Green anarchism |

|---|

|

|

Green anarchism is a school of thought that puts a particular emphasis on environmental issues. A significant early influence was the thought of the American anarchist Henry David Thoreau and his book Walden[118] as well as Leo Tolstoy[119] and Élisée Reclus.[120][121] In the late 19th century, anarcho-naturism emerged as the fusion of anarchism and naturist philosophies within individualist anarchist[122][123][124] circles in Cuba,[125] France,[126][127] Portugal,[118][119] and Spain.[119][127][128][129][130]

Important contemporary currents are anarcho-primitivism and social ecology.[131] An important meeting place for international libertarian socialism in the early 1990s was the journal Democracy & Nature, in which prominent activists and theorists such as Takis Fotopoulos, Noam Chomsky,[132] Murray Bookchin, and Cornelius Castoriadis wrote.[133]

Political roots

Peasant revolts in the post-Reformation era

For Roderick T. Long, libertarian socialists claim the 17th century English Levellers among their ideological forebears.[134] Various libertarian socialist authors have identified the written work of English Protestant social reformer Gerrard Winstanley and the social activism of his group (the Diggers) as anticipating this line of thought.[135][136] For anarchist historian George Woodcock, although Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first writer to call himself an anarchist, at least two predecessors outlined systems that contain all the essential elements of anarchism. The first was Gerrard Winstanley (1609 – c. 1660), a linen draper who led the small movement of the Diggers during the Commonwealth. Winstanley and his followers protested in the name of radical Christianity against the economic distress that followed the English Civil War and against the inequality that the grandees of the New Model Army seemed intent on preserving.[137]

In 1649–1650, the Diggers squatted on stretches of common land in southern England and attempted to set up communities based on work on the land and sharing goods. The communities failed, but a series of pamphlets by Winstanley survived, of which The New Law of Righteousness (1649) was the most important. Advocating a rational Christianity, Winstanley equated Christ with "the universal liberty" and declared the universally corrupting nature of authority. He saw "an equal privilege to share in the blessing of liberty" and detected a close link between the institution of property and the lack of freedom.[137]

Murray Bookchin stated: "In the modern world, anarchism first appeared as a movement of the peasantry and yeomanry against declining feudal institutions. In Germany its foremost spokesman during the Peasant Wars was Thomas Muenzer. The concepts held by Muenzer and Winstanley were superbly attuned to the needs of their time – a historical period when the majority of the population lived in the countryside and when the most militant revolutionary forces came from an agrarian world. It would be painfully academic to argue whether Muenzer and Winstanley could have achieved their ideals. What is of real importance is that they spoke to their time; their anarchist concepts followed naturally from the rural society that furnished the bands of the peasant armies in Germany and the New Model in England".[138]

Age of Enlightenment

For Long, libertarian socialists also often share a view of ancestry in the 18th-century French Encyclopédistes alongside Thomas Jefferson[139][140][141] and Thomas Paine.[134] A more often mentioned name is that of English enlightenment thinker William Godwin.[142]

For Woodcock, a more elaborate sketch of anarchism—although still without the name—was provided by William Godwin in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793). Godwin was a gradualist anarchist rather than a revolutionary anarchist as he differed from most later anarchists in preferring above revolutionary action the gradual and—as it seemed to him—more natural process of discussion among men of goodwill, by which he hoped the truth would eventually triumph through its power. Godwin, influenced by the English tradition of Dissent and the French philosophy of the Enlightenment, put forward in a developed form the basic anarchist criticisms of the state, accumulated property, and the delegation of authority through democratic procedure.[137]

Noam Chomsky considers libertarian socialism "the proper and natural extension" of classical liberalism "into the era of advanced industrial society".[143] Chomsky sees libertarian socialist ideas as the descendants of the classical liberal ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[144][145] arguing that his ideological position revolves around "nourishing the libertarian and creative character of the human being".[146] Chomsky envisions an anarcho-syndicalist future with direct worker control of the means of production and government by workers' councils which would select representatives to meet together at general assemblies.[147] In Jefferson's words, the point of this self-governance is to make each citizen "a direct participator in the government of affairs".[148] Chomsky believes that there will be no need for political parties.[149] Chomsky believes individuals can gain job satisfaction and a sense of fulfilment and purpose by controlling their productive life.[150] Chomsky argues that unpleasant and unpopular jobs could be fully automated, carried out by specially renumerated workers, or shared among everyone.[151]

During the French Revolution, Sylvain Maréchal demanded "the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth" in his Manifesto of the Equals (1796) and looked forward to the disappearance of "the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed".[42][43][152] The term anarchist first entered the English language in 1642 during the English Civil War as a term of abuse used by Royalists against their Roundhead opponents.[153] By the time of the French Revolution, some, such as the Enragés, began to use the term positively[154] in opposition to Jacobin centralisation of power, seeing revolutionary government as oxymoronic.[153] By the turn of the 19th century, the English term anarchism had lost its initial negative connotation.[153]

Romantic era and utopian socialism

In his preface to Peter Kropotkin's book The Conquest of Bread, Kent Bromley considered early French socialist Charles Fourier to be the founder of the libertarian branch of socialist thought as opposed to the authoritarian socialist ideas of François-Noël Babeuf and Philippe Buonarroti.[44] Anarchist Hakim Bey describes Fourier's ideas as follows: "In Fourier's system of Harmony all creative activity including industry, craft, agriculture, etc. will arise from liberated passion – this is the famous theory of "attractive labor." Fourier sexualizes work itself – the life of the Phalanstery is a continual orgy of intense feeling, intellection, & activity, a society of lovers & wild enthusiasts". Fourierism manifested itself in the middle of the 19th century when hundreds of communes (phalansteries) were founded on Fourierist principles in France, North America, Mexico, South America, Algeria, and Yugoslavia. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Friedrich Engels and Peter Kropotkin read him with fascination, as did André Breton and Roland Barthes.[155] In his influential work Eros and Civilization, Herbert Marcuse praised Fourier by saying that he "comes closer than any other utopian socialist to elucidating the dependence of freedom on non-repressive sublimation".[156]

Anarchist Peter Sabatini reports that in the United States in the early to mid-19th century, "there appeared an array of communal and "utopian" counterculture groups (including the so-called free love movement). William Godwin's anarchism exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren (1798–1874), considered to be the first individualist anarchist".[157]

Anarchism

As Albert Meltzer and Stuart Christie stated in their book The Floodgates of Anarchy:

[Anarchism] has its particular inheritance, part of which it shares with socialism, giving it a family resemblance to certain of its enemies. Another part of its inheritance it shares with liberalism, making it, at birth, kissing-cousins with American-type radical individualism, a large part of which has married out of the family into the Right Wing and is no longer on speaking terms.[158]

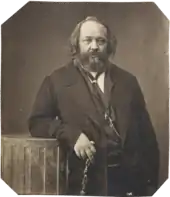

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who is often considered the father of modern anarchism, coined the phrase "Property is theft!" to describe part of his view on the complex nature of ownership in relation to freedom. When he said property is theft, he was referring to the capitalist he believed stole profit from labourers. For Proudhon, the capitalist's employee was "subordinated, exploited: his permanent condition is one of obedience".[159]

Seventeen years (1857) after Proudhon first called himself an anarchist (1840), anarcho-communist Joseph Déjacque was the first to describe himself as a libertarian.[160] Outside the United States, the term libertarian generally refers to anti-authoritarian, anticapitalist ideologies.[161]

Libertarian socialism has its roots in both classical liberalism and socialism, though it is often in conflict with liberalism (especially neoliberalism and right-libertarianism) and authoritarian state socialism simultaneously. While libertarian socialism has roots in socialism and liberalism, different forms have different levels of influence from the two traditions. For instance, mutualist anarchism is more influenced by liberalism, while communist and syndicalist anarchism are more influenced by socialism. However, mutualist anarchism originates in 18th- and 19th-century European socialism (such as Fourierian socialism),[162][163] while communist and syndicalist anarchism have their earliest origins in early 18th-century liberalism (such as the French Revolution).[152]

Anarchism posed an early challenge to the vanguardism and statism it detected in important sectors of the socialist movement. As such: "The consequences of the growth of parliamentary action, ministerialism, and party life, charged the anarchists, would be de-radicalism and embourgeoisiement. Further, state politics would subvert both true individuality and true community. In response, many anarchists refused Marxist-type organisation, seeking to dissolve or undermine power and hierarchy by loose political-cultural groupings or by championing organisation by a single, simultaneously economic and political administrative unit (Ruhle, syndicalism). The power of the intellectual and of science were also rejected by many anarchists: "In conquering the state, in exalting the role of parties, they [intellectuals] reinforce the hierarchical principle embodied in political and administrative institutions". Revolutions could only come through force of circumstances and/or the inherently rebellious instincts of the masses (the "instinct for freedom") (Bakunin, Chomsky), or in Bakunin's words: "All that individuals can do is to clarify, propagate, and work out ideas corresponding to the popular instinct".[164]

Marxism

Marxism started to develop a libertarian strand of thought after specific circumstances. Chamsy Ojeili said: "One does find early expressions of such perspectives in [William] Morris and the Socialist Party of Great Britain (the SPGB), then again around the events of 1905, with the growing concern at the bureaucratisation and de-radicalisation of international socialism".[164] Morris established the Socialist League in December 1884, which by Friedrich Engels and Eleanor Marx encouraged. As the leading figure in the organization, Morris embarked on a relentless series of speeches and talks on street corners in working men's clubs and lecture theatres across England and Scotland. From 1887, anarchists began to outnumber socialists in the Socialist League.[165] The 3rd Annual Conference of the League, held in London on 29 May 1887, marked the change with a majority of the 24 branch delegates voting in favour of an anarchist-sponsored resolution declaring: "This conference endorses the policy of abstention from parliamentary action, hitherto pursued by the League, and sees no sufficient reason for altering it".[166] Morris played peacemaker, but he sided with the anti-Parliamentarians, who won control of the League, which consequently lost the support of Engels and saw the departure of Eleanor Marx and her partner Edward Aveling to form the separate Bloomsbury Socialist Society.

However, "the most important ruptures are to be traced to the insurgency during and after the First World War. Disillusioned with the capitulation of the social democrats, excited by the emergence of workers' councils, and slowly distanced from Leninism, many communists came to reject the claims of socialist parties and to put their faith instead in the masses". For these socialists, "[t]he intuition of the masses in action can have more genius in it than the work of the greatest individual genius". Rosa Luxemburg's workerism and spontaneism are exemplary of positions later taken up by the far-left of the period—Antonie Pannekoek, Roland Holst and Herman Gorter in the Netherlands, Sylvia Pankhurst in Britain, Antonio Gramsci in Italy and György Lukács in Hungary. In these formulations, the dictatorship of the proletariat was to be the dictatorship of a class, "not of a party or of a clique".[164] However, within this line of thought, "[t]he tension between anti-vanguardism and vanguardism has frequently resolved itself in two diametrically opposed ways: the first involved a drift towards the party; the second saw a move towards the idea of complete proletarian spontaneity. [...] The first course is exemplified most clearly in Gramsci and Lukacs. [...] The second course is illustrated in the tendency, developing from the Dutch and German far-lefts, which inclined towards the complete eradication of the party form".[164]

In the emerging Soviet Union, left-wing uprisings appeared against the Bolsheviks, a series of rebellions and uprisings against the Bolsheviks led or supported by left-wing groups including Socialist Revolutionaries,[167] Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and anarchists.[168] Some supported the White Movement, while some tried to be an independent force. The uprisings started in 1918 and continued through the Russian Civil War and until 1922. In response, the Bolsheviks increasingly abandoned attempts to get these groups to join the government and suppressed them with force. "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder is a work by Vladimir Lenin attacking assorted critics of the Bolsheviks who claimed positions to their left.

For many Marxian libertarian socialists, "the political bankruptcy of socialist orthodoxy necessitated a theoretical break. This break took a number of forms. The Bordigists and the SPGB championed a super-Marxian intransigence in theoretical matters. Other socialists made a return "behind Marx" to the anti-positivist programme of German idealism. Libertarian socialism has frequently linked its anti-authoritarian political aspirations with this theoretical differentiation from orthodoxy. [...] Karl Korsch [...] remained a libertarian socialist for a large part of his life and because of the persistent urge towards theoretical openness in his work. Korsch rejected the eternal and static, and he was obsessed by the essential role of practice in a theory's truth. For Korsch, no theory could escape history, not even Marxism. In this vein, Korsch even credited the stimulus for Marx's Capital to the movement of the oppressed classes".[164]

In rejecting capitalism and the state, some libertarian Marxists align themselves with anarchists in opposition to capitalist representative democracy and authoritarian forms of Marxism. Although anarchists and Marxists share an ultimate goal of a stateless society, anarchists criticise most Marxists for advocating a transitional phase under which the state is used to achieve this aim. Nonetheless, libertarian Marxist tendencies such as autonomist Marxism and council communism have historically been intertwined with the anarchist movement. Anarchist movements have come into conflict with both capitalist and Marxist forces, sometimes at the same time—as in the Spanish Civil War—though, as in that war, Marxists themselves are often divided in support or opposition to anarchism. Other political persecutions under bureaucratic parties have resulted in a strong historical antagonism between anarchists and libertarian Marxists on the one hand and Leninist Marxists and their derivatives, such as Maoists, on the other. In recent history, libertarian socialists have repeatedly formed temporary alliances with Marxist–Leninist groups to protest against institutions they both reject. Part of this antagonism can be traced to the International Workingmen's Association, the First International, a congress of radical workers, where Mikhail Bakunin, who was fairly representative of anarchist views; and Karl Marx, whom anarchists accused of being an "authoritarian", came into conflict on various issues. Bakunin's viewpoint on the illegitimacy of the state as an institution and the role of electoral politics was starkly counterposed to Marx's views in the First International. Marx and Bakunin's disputes eventually led to Marx taking control of the First International and expelling Bakunin and his followers from the organization. This was the beginning of a long-running feud and schism between libertarian socialists and what they call "authoritarian communists" or just "authoritarians". Some Marxists have formulated views that closely resemble syndicalism and thus express more affinity with anarchist ideas. Several libertarian socialists, notably Noam Chomsky, believe that anarchism shares much in common with specific variants of Marxism, such as the council communism of Marxist Anton Pannekoek. In his Notes on Anarchism, Chomsky suggests the possibility "that some form of council communism is the natural form of revolutionary socialism in an industrial society. It reflects the belief that democracy is severely limited when the industrial system is controlled by any form of autocratic elite, whether of owners, managers, and technocrats, a 'vanguard' party, or a State bureaucracy".[169]

In the mid-20th century, some libertarian socialist groups emerged from disagreements with Trotskyism which presented itself as Leninist anti-Stalinism. As such, the French group Socialisme ou Barbarie emerged from the Trotskyist Fourth International, where Cornelius Castoriadis and Claude Lefort constituted a Chaulieu–Montal tendency in the French Parti Communiste Internationaliste in 1946. In 1948, they experienced their "final disenchantment with Trotskyism",[170] leading them to break away to form Socialisme ou Barbarie, whose journal began appearing in March 1949. Castoriadis later said of this period that "the main audience of the group and of the journal was formed by groups of the old, radical left: Bordigists, council communists, some anarchists and some offspring of the German "left" of the 1920s".[171] Also, in the United Kingdom, the group Solidarity was founded in 1960 by a small group of expelled members of the Trotskyist Socialist Labour League. Almost from the start, it was strongly influenced by the French Socialisme ou Barbarie group, in particular by its intellectual leader Cornelius Castoriadis, whose essays were among the many pamphlets Solidarity produced. The group's intellectual leader was Chris Pallis, who wrote under the name Maurice Brinton.[172]

In the People's Republic of China (PRC) since 1967, the terms ultra-left and left communist refer to political theory and practice self-defined as further left than that of the central Maoist leaders at the height of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (GPCR). The terms are also used retroactively to describe some early 20th-century Chinese anarchist orientations. As a slur, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has used the term "ultra-left" more broadly to denounce any orientation it considers further left than the party line. According to the latter usage, in 1978, the CCP Central Committee denounced the Mao Zedong line as ultra-left from 1956 until he died in 1976. The term ultra-left refers to those GPCR rebel positions that diverged from the central Maoist line by identifying an antagonistic contradiction between the CCP-PRC party-state itself and the masses of workers and peasants[173] conceived as a single proletarian class divorced from any meaningful control over production or distribution. Whereas the central Maoist line maintained that the masses controlled the means of production through the party's mediation, the ultra-left argued that the objective interests of bureaucrats were structurally determined by the centralist state-form in direct opposition to the objective interests of the masses, regardless of however socialist a given bureaucrat's thought might be. Whereas the central Maoist leaders encouraged the masses to criticize reactionary ideas and habits among the alleged 5% of bad cadres, giving them a chance to "turn over a new leaf" after they had undergone "thought reform", the ultra-left argued that cultural revolution had to give way to political revolution "in which one class overthrows another class".[174][175]

In 1969, French platformist anarcho-communist Daniel Guérin published an essay called "Libertarian Marxism?" in which he dealt with the debate between Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International and afterwards, he suggested that "Libertarian [M]arxism rejects determinism and fatalism, giving the greater place to individual will, intuition, imagination, reflex speeds, and to the deep instincts of the masses, which are more far-seeing in hours of crisis than the reasonings of the 'elites'; libertarian [M]arxism thinks of the effects of surprise, provocation and boldness, refuses to be cluttered and paralysed by a heavy 'scientific' apparatus, doesn't equivocate or bluff, and guards itself from adventurism as much as from fear of the unknown".[176] In the United States, there existed from 1970 to 1981 the publication Root & Branch[177] which had as a subtitle "A Libertarian Marxist Journal".[178] In 1974, the journal Libertarian Communism was started in the United Kingdom by a group inside the SPGB.[179]

Autonomist Marxism, neo-Marxism and Situationist theory are also regarded as anti-authoritarian variants of Marxism that are firmly within the libertarian socialist tradition. As such, "[i]n New Zealand, no situationist group was formed, despite the attempts of Grant McDonagh. Instead, McDonagh operated as an individual on the periphery of the anarchist milieu, co-operating with anarchists to publish several magazines, such as Anarchy and KAT. The latter called itself 'an anti-authoritarian spasmodical' of the 'libertarian ultra-left (situationists, anarchists and libertarian socialists)'".[180] For libcom.org: "In the 1980s and 90s, a series of other groups developed, influenced also by much of the above work. The most notable are Kolinko, Kurasje and Wildcat in Germany, Aufheben in England, Theorie Communiste in France, TPTG in Greece and Kamunist Kranti in India. They are also connected to other groups in other countries, merging autonomia, operaismo, Hegelian Marxism, the work of the JFT, Open Marxism, the ICO, the Situationist International, anarchism and post-68 German Marxism".[181] Related to this were intellectuals who were influenced by Italian left communist Amadeo Bordiga but disagreed with his Leninist positions. These included the French publication Invariance, edited by Jacques Camatte, published since 1968, and Gilles Dauvé, who published Troploin with Karl Nesic.

Notable tendencies

Anarchist

Historically, anarchism and libertarian socialism have mainly been synonymous.[182] Principally this regards the currents of classical anarchism, developed in the 19th century, in their commitments to autonomy and freedom, decentralization, opposing hierarchy, and opposing the vanguardism of authoritarian socialism.

Anarcho-syndicalist Gaston Leval explained: "We therefore foresee a Society in which all activities will be coordinated, a structure that has, at the same time, sufficient flexibility to permit the greatest possible autonomy for social life, or for the life of each enterprise, and enough cohesiveness to prevent all disorder. [...] In a well-organised society, all of these things must be systematically accomplished by means of parallel federations, vertically united at the highest levels, constituting one vast organism in which all economic functions will be performed in solidarity with all others and that will permanently preserve the necessary cohesion".[183]

Mutualism

Mutualism began as a 19th-century socialist movement adopted and developed by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon into the first anarchist economic theory. Mutualism is based on a version of the labour theory of value, holding that when labour or its product is sold, it ought to receive in exchange goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[184] It considers anything less exploitation, labour theft, or usury. Mutualists advocate social ownership and believe a free labour market would allow for conditions of equal income in proportion to exerted labour.[185][186] As Jonathan Beecher puts it, the mutualist aim was to "emancipate labor from the constraints imposed by capital".[187] Proudhon believed that an individual only had a right to land while using or occupying it. If the individual ceases doing so, it reverts to unowned land.[188]

Some individualist anarchists, such as Benjamin Tucker, were influenced by Proudhon's mutualism, but they did not call for association in large enterprises like him.[189] Mutualist ideas found fertile ground in the 19th century in Spain. In Spain, Ramón de la Sagra established the anarchist journal El Porvenir in La Coruña in 1845, inspired by Proudhon's ideas.[190] The Catalan politician Francesc Pi i Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into Spanish[191] and later briefly became president of Spain in 1873 while being the leader of the Democratic Republican Federal Party.

According to George Woodcock, "[t]hese translations were to have a profound and lasting effect on the development of Spanish anarchism after 1870, but before that time Proudhonian ideas, as interpreted by Pi, already provided much of the inspiration for the federalist movement which sprang up in the early 1860's".[191] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "[d]uring the Spanish revolution of 1873, Pi y Margall attempted to establish a decentralized, or 'cantonalist,' political system on Proudhonian lines".[190] Kevin Carson is a contemporary mutualist theorist who is the author of Studies in Mutualist Political Economy.[192]

Social anarchism

Social anarchism is a branch of anarchism emphasizing social ownership, mutual aid and workers' self-management. Social anarchism has been the dominant form of classical anarchism and includes the major collectivist, communist and syndicalist schools of anarchist thought. Social anarchism is used in contrast to individualist anarchism to describe the theory that emphasizes the communitarian and cooperative aspects of anarchist theory while also opposing authoritarian forms of communitarianism associated with groupthink and collective conformity, favouring a reconciliation between individuality and sociality.

Social anarchists oppose private ownership of the means of production, seeing it as a source of inequality. Instead, they advocate social ownership through collective ownership as with Bakuninists and collectivist anarchists, common ownership as with communist anarchists, and cooperative ownership as with syndicalist anarchists; or other forms. Social anarchism comes in both peaceful and insurrectionary tendencies, as well as both platformist and anti-organizationalist tendencies. It has operated heavily within workers' movements, trade unions and labour syndicates, emphasizing the liberation of workers through class struggle.

The best-known examples of social anarchist societies are the Makhnovshchina, the Korean People's Association in Manchuria, and the anarchist territories of the Spanish Revolution.[193]

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is a set of several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems.[194][195] Anarchists such as Luigi Galleani and Errico Malatesta have seen no contradiction between individualist anarchism and social anarchism,[196] with the latter especially seeing issues not between the two forms of anarchism but between anarchists and non-anarchists.[197] Anarchists such as Benjamin Tucker argued that it was "not Socialist Anarchism against Individualist Anarchism, but of Communist Socialism against Individualist Socialism".[198] Tucker further noted that "the fact that State Socialism has overshadowed other forms of Socialism gives it no right to a monopoly of the Socialistic idea".[199]

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist,[200] and the four-page weekly paper he edited in 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published.[201] For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent [...] that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews [...]. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[202] Later, the American individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker "was against both the state and capitalism, against both oppression and exploitation. While not against the market and property, he was firmly against capitalism as it was, in his eyes, a state-supported monopoly of social capital (tools, machinery, etc.) which allows owners to exploit their employees, i.e., to avoid paying workers the full value of their labour. He thought that the "labouring classes are deprived of their earnings by usury in its three forms, interest, rent and profit", therefore "Liberty will abolish interest; it will abolish profit; it will abolish monopolistic rent; it will abolish taxation; it will abolish the exploitation of labour; it will abolish all means whereby any labourer can be deprived of any of his product". This stance puts him squarely in the libertarian socialist tradition, and Tucker often referred to himself as a socialist and considered his philosophy anarchistic socialism.[203][204]

French individualist anarchist Émile Armand clearly shows opposition to capitalism and centralized economies when he said that the individualist anarchist "inwardly he remains refractory – fatally refractory – morally, intellectually, economically (The capitalist economy and the directed economy, the speculators and the fabricators of single are equally repugnant to him.)".[205] The Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Giménez Igualada thought that "capitalism is an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously...That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State".[206] His view on class division and technocracy are as follows: "Since when no one works for another, the profiteer from wealth disappears, just as government will disappear when no one pays attention to those who learned four things at universities and from that fact they pretend to govern men. Big industrial enterprises will be transformed by men in big associations in which everyone will work and enjoy the product of their work. And from those easy as well as beautiful problems anarchism deals with and he who puts them in practice and lives them are anarchists. [...] The priority which without rest an anarchist must make is that in which no one has to exploit anyone, no man to no man, since that non-exploitation will lead to the limitation of property to individual needs".[207]

The anarchist[208] writer and Bohemian Oscar Wilde wrote in his famous essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism that "[a]rt is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force. There lies its immense value. For what it seeks is to disturb monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine".[209] For anarchist historian George Woodcock, "Wilde's aim in The Soul of Man Under Socialism is to seek the society most favorable to the artist [...] for Wilde art is the supreme end, containing within itself enlightenment and regeneration, to which all else in society must be subordinated. [...] Wilde represents the anarchist as aesthete".[210] In a socialist society, people will have the possibility to realise their talents as "each member of the society will share in the general prosperity and happiness of the society". Wilde added that "upon the other hand, Socialism itself will be of value simply because it will lead to individualism" since individuals will no longer need to fear poverty or starvation. This individualism would, in turn, protect against governments "armed with economic power as they are now with political power" over their citizens. However, Wilde advocated non-capitalist individualism, saying that "of course, it might be said that the Individualism generated under conditions of private property is not always, or even as a rule, of a fine or wonderful type" a critique which is "quite true".[211] In Wilde's imagination, in this way socialism would free men from manual labour and allow them to devote their time to creative pursuits, thus developing their soul. He ended by declaring: "The new individualism is the new hellenism".[211]

Marxist

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

Libertarian Marxism is a broad scope of economic and political philosophies that emphasize the anti-authoritarian aspects of Marxism.[212] Early currents of libertarian Marxism, known as left communism,[213] emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism[214] and its derivatives such as Stalinism, Maoism and Trotskyism.[215] Libertarian Marxism is also critical of reformist positions such as those held by social democrats.[216] Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France;[217] emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its destiny without the need for a revolutionary party or state to mediate or aid its liberation.[218] Along with anarchism, libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism.[219]

Libertarian Marxism includes such currents as Luxemburgism, council communism, left communism, Socialisme ou Barbarie, the Johnson–Forest tendency, world socialism, Lettrism/Situationism and autonomism/workerism and New Left.[220] Libertarian Marxism has often strongly influenced both post-left and social anarchists. Notable theorists of libertarian Marxism have included Anton Pannekoek, Raya Dunayevskaya, C. L. R. James, Antonio Negri, Cornelius Castoriadis, Maurice Brinton, Guy Debord, Daniel Guérin, Ernesto Screpanti and Raoul Vaneigem.

De Leonism

De Leonism is a form of syndicalist Marxism developed by Daniel De Leon. De Leon was an early leader of the first United States socialist political party, the Socialist Labor Party of America. De Leon combined the rising theories of syndicalism in his time with orthodox Marxism. According to De Leonist theory, militant industrial unions (specialized trade unions) and a party promoting industrial unionist ideas are the vehicles of class struggle.

Industrial unions serving the proletariat's interests will bring about the change needed to establish a socialist system. The only way this differs from some currents in anarcho-syndicalism is that according to De Leonist thinking, a revolutionary political party is also necessary to fight for the proletariat on the political field. De Leonism also lies outside the Leninist tradition of communism. It predates Leninism, as De Leonism's principles developed in the early 1890s with De Leon's assuming leadership of the SLP, whereas Leninism and its vanguard party idea took shape after the 1902 publication of Lenin's What Is To Be Done?

The highly decentralized and democratic nature of the proposed De Leonist government contrasts the democratic centralism of Marxism–Leninism and what they see as the dictatorial nature of the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, and other communist states. The success of the De Leonist plan depends on achieving majority support among the people both in the workplace and at the polls, in contrast to the Leninist notion that a small vanguard party should lead the working class to carry out the revolution.

Council communism

Council communism is a radical left-wing movement that originated in Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s. Its primary organization was the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD). Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within Marxism and libertarian socialism. In contrast to those of social democracy and Leninist communism, the central argument of council communism is that workers' councils arising in the factories and municipalities are the natural and legitimate form of working-class organisation and government power. This view is opposed to the reformist and Bolshevik stress on vanguard parties, parliaments, or the state. The core principle of council communism is that the state and the economy should be managed by workers' councils, composed of delegates elected at workplaces and recallable at any moment. As such, council communists oppose state-run bureaucratic socialism. They also oppose the idea of a revolutionary party since council communists believe a revolution led by a party will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. Council communists support a workers' democracy, which they want to produce through a federation of workers' councils.

The Russian term for council is soviet, and during the early years of the revolution, worker's councils were politically significant in Russia. It was to take advantage of the aura of workplace power that the word became used by Vladimir Lenin for various political organs. The name Supreme Soviet, by which the parliament was called, and that of the Soviet Union make use of this terminology, but they do not imply any decentralization. Furthermore, council communists critiqued the Soviet Union as a capitalist state, believing that the Bolshevik revolution in Russia became a "bourgeois revolution" when a party bureaucracy replaced the old feudal aristocracy. Although most felt the Russian Revolution was working class in character, they believed that since capitalist relations still existed (because the workers had no say in running the economy), the Soviet Union ended up as a state capitalist country, with the state replacing the individual capitalist. Council communists support workers' revolutions, but they oppose one-party dictatorships. Council communists also believed in diminishing the party's role to one of agitation and propaganda, rejected all participation in elections or parliament and argued that workers should leave the reactionary trade unions and form one big revolutionary union.

Left communism

| Part of a series on |

| Left communism |

|---|

|

|

Left communism is the range of communist viewpoints held by the communist left, which criticizes the political ideas of the Bolsheviks at specific periods from a position that is asserted to be more authentically Marxist and proletarian than the views of Leninism held by the Communist International after its first and during its second congress. Left communists see themselves to the left of Leninists (whom they tend to see as the "left of capital", not socialists), anarchists (some of whom they consider internationalist socialists), as well as some other revolutionary socialist tendencies (for example, De Leonists, whom they tend to see as being internationalist socialists only in limited instances). Although she lived before left communism became a distinct tendency, Rosa Luxemburg has heavily influenced most left communists politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Amadeo Bordiga, Herman Gorter, Anton Pannekoek, Otto Rühle, Karl Korsch, Sylvia Pankhurst and Paul Mattick.

Prominent left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Current and the Internationalist Communist Tendency. Different factions from the old Bordigist International Communist Party are also considered left communist organizations.

Johnson–Forest tendency

The Johnson–Forest tendency is a radical left tendency in the United States associated with Marxist humanist theorists C.L.R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya, who used the pseudonyms J. R. Johnson and Freddie Forest, respectively. They were joined by Grace Lee Boggs, a Chinese American woman considered the third founder. After leaving the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, Johnson–Forest founded their organization for the first time, called Correspondence. This group changed its name to the Correspondence Publishing Committee the following year. However, tensions that had surfaced earlier presaged a split, which took place in 1955. Through his theoretical and political work of the late 1940s, James concluded that a vanguard party was no longer necessary because the masses had absorbed its teachings. In 1956, James would see the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 as confirmation. Those who endorsed the politics of James took the name Facing Reality after the 1958 book by James, co-written with Grace Lee Boggs and Pierre Chaulieu (a pseudonym for Cornelius Castoriadis) on the Hungarian working class revolt of 1956.

Socialisme ou Barbarie

Socialisme ou Barbarie (Socialism or Barbarism) was a French-based radical libertarian socialist group of the post-World War II period (the name comes from a phrase Friedrich Engels used and was cited by Rosa Luxemburg in the 1916 essay The Junius Pamphlet).[221] It existed from 1948 until 1965. The animating personality was Cornelius Castoriadis, also known as Pierre Chaulieu or Paul Cardan.[222] Because he explicitly rejected Leninist vanguardism and criticised spontaneism, for Castoriadis, "the emancipation of the mass of people was the task of those people; however, the socialist thinker could not simply fold his or her arms". Castoriadis argued that the special place accorded to the intellectual should belong to each autonomous citizen. However, he rejected attentisme, maintaining that in the struggle for a new society, intellectuals needed to "place themselves at a distance from the everyday and from the real".[164] Political philosopher Claude Lefort was impressed by Cornelius Castoriadis when he first met him. They published On the Regime and Against the Defence of the USSR, a critique of the Soviet Union and its Trotskyist supporters. They suggested that a social layer of bureaucrats dominated the Soviet Union and that it consisted of a new kind of society as aggressive as Western European societies. Later, he also published in Socialisme ou Barbarie.

Situationist International

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Situationism |

|---|

|

The Situationist International was a restricted group of international revolutionaries founded in 1957 and which had its peak in its influence on the unprecedented general wildcat strikes of May 1968 in France. With their ideas rooted in Marxism and the 20th-century European artistic avant-gardes, they advocated experiences of life being alternative to those admitted by the capitalist order for the fulfilment of human primitive desires and the pursuit of a superior passional quality. For this purpose, they suggested and experimented with the "construction of situations", namely setting up environments favourable for fulfilling such desires. Using methods drawn from the arts, they developed a series of experimental fields of study for constructing such situations, like unitary urbanism and psychogeography. In this vein, a major theoretical work which emerged from this group was Raoul Vaneigem's The Revolution of Everyday Life.[223]

They fought against the main obstacle to fulfilling such superior passional living, identified by them in advanced capitalism. Their critical theoretical work peaked in the highly influential book The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord. Debord argued in 1967 that spectacular features like mass media and advertising have a central role in an advanced capitalist society, which is to show a fake reality to mask the actual capitalist degradation of human life. To overthrow such a system, the Situationist International supported the May 1968 revolts and asked the workers to occupy the factories and to run them with direct democracy through workers' councils composed of instantly revocable delegates.

After publishing the magazine's last issue, an analysis of the May 1968 revolts and the strategies that will need to be adopted in future revolutions,[224] the Situationist International was dissolved in 1972.[225]

Autonomism

Autonomism is a set of left-wing political and social movements and theories close to the socialist movement. It emerged as an identifiable theoretical system in Italy in the 1960s from workerist (operaismo) communism. Through translations made available by Danilo Montaldi and others, the Italian autonomists drew upon previous activist research in the United States by the Johnson–Forest tendency and in France by the group Socialisme ou Barbarie. Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tendencies became significant after the influence of the Situationists, the failure of Italian far-left movements in the 1970s and the emergence of many important theorists, including Antonio Negri who had contributed to the 1969 founding of Potere Operaio, and Mario Tronti, Paolo Virno, and Franco "Bifo" Berardi.

Unlike other forms of Marxism, autonomist Marxism emphasises the ability of the working class to force changes to the organization of the capitalist system independent of the state, trade unions or political parties. Autonomists are less concerned with party political organization than other Marxists, focusing instead on self-organized action outside traditional organizational structures. Autonomist Marxism is thus a "bottom up" theory that draws attention to activities that autonomists see as everyday working class resistance to capitalism, such as absenteeism, slow working, and socialization in the workplace.

All this influenced the German and Dutch autonomen, the worldwide Social Centre movement, and today is influential in Italy, France, and to a lesser extent, the English-speaking countries. Those who describe themselves as autonomists now vary from Marxists to post-structuralists and anarchists. The autonomist Marxist and autonomen movements inspired some on the revolutionary left in English-speaking countries, particularly among anarchists, who have adopted autonomist tactics. Some English-speaking anarchists even describe themselves as autonomists. The Italian operaismo movement also influenced Marxist academics such as Harry Cleaver, John Holloway, Steve Wright and Nick Dyer-Witheford. Today, it is also associated with the publication Multitudes.[226]

Other

Other libertarian socialist currents include post-classical anarchist tendencies and tendencies that cannot be easily classified within the anarchist/Marxist division.

Democratic socialism

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon ran for the French constituent assembly in April 1848, but he was not elected, although his name appeared on the ballots in Paris, Lyon, Besançon, and Lille. He was successful in the complementary elections of June 4. The Catalan politician Francesc Pi i Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into Spanish and later briefly became president of Spain in 1873 while being the leader of the Federal Democratic Republican Party.[191]

.JPG.webp)

For prominent anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker:

The first movement of the Spanish workers was strongly influenced by the ideas of Pi y Margall, leader of the Spanish Federalists and disciple of Proudhon. Pi y Margall was one of the outstanding theorists of his time and had a powerful influence on the development of libertarian ideas in Spain. His political ideas had much in common with those of Richard Price, Joseph Priestly [sic], Thomas Paine, Jefferson, and other representatives of the Anglo-American liberalism of the first period. He wanted to limit the power of the state to a minimum and gradually replace it by a Socialist economic order.[227]

Pi i Margall was a dedicated theorist in his own right, especially through book-length works such as La reacción y la revolución (Reaction and revolution, from 1855), Las nacionalidades (Nationalities, 1877) and La Federación (Federation) from 1880. On the other hand, Fermín Salvochea was the mayor of the city of Cádiz and the president of the province of Cádiz. He was one of the main propagators of anarchist thought in that area in the late 19th century and is considered perhaps the most beloved figure in the Spanish anarchist movement of the 19th century.[228][229] Ideologically, he was influenced by Charles Bradlaugh, Robert Owen and Thomas Paine, whose works he had studied during his stay in England, and by Peter Kropotkin, whom he read later. In Spain, he had contact with the anarchist thinkers and members of the Bakuninist Alliance, including Anselmo Lorenzo and Francisco Mora.[228]

In 1950, a clandestine group formed within the Francophone Anarchist Federation (FA) called Organisation Pensée Bataille (OPB), led by the platformist George Fontenis.[230] The OPB pushed for a move which saw the FA change its name to the Fédération Communiste Libertaire (FCL) after the 1953 Congress in Paris, while an article in Le Libertaire indicated the end of the cooperation with the French Surrealist Group led by André Breton. The new decision-making process was founded on unanimity, as each person had a right of veto on the orientations of the federation. The FCL published the same year Manifeste du communisme libertaire. Several groups quit the FCL in December 1955, disagreeing with the decision to present "revolutionary candidates" at the legislative elections. On 15–20 August 1954, the fifth intercontinental plenum of the CNT took place. A group called Entente anarchiste (Anarchist Agreement) appeared, which was formed of militants who did not like the new ideological orientation that the OPB was giving the FCL, considering it authoritarian and almost Marxist.[231] The FCL lasted until 1956, just after participating in state legislative elections with ten candidates. This move alienated some members of the FCL and thus led to the end of the organization.[230]

There was a strong left-libertarian current in the British labour movement, and the term "libertarian socialist" has been applied to many democratic socialists, including some prominent members of the British Labour Party. The Socialist League was formed in 1885 by William Morris and others critical of the authoritarian socialism of the Social Democratic Federation. It was involved in the new unionism, the rank-and-file union militancy of the 1880s–1890s, which anticipated syndicalism in some fundamental ways (Tom Mann, a New Unionist leader, was one of the first British syndicalists). Anarchists dominated the Socialist League by the 1890s.[232] The Independent Labour Party (ILP), formed at that time, drew more on the nonconformist religious traditions in the British working class than on Marxist theory and had a libertarian socialist strain. Others in the tradition of the ILP and described as libertarian socialists included Michael Foot and, most importantly, G. D. H. Cole. Labour Party minister Peter Hain[233] has written in support of libertarian socialism, identifying an axis involving a "bottom-up vision of socialism, with anarchists at the revolutionary end and democratic socialists [such as himself] at its reformist end" as opposed to the axis of state socialism with Marxist–Leninists at the revolutionary end and social democrats at the reformist end.[234] Another recent mainstream Labour politician who has been described as a libertarian socialist is Robin Cook.[235] Defined in this way, libertarian socialism in the contemporary political mainstream is distinguished from modern social democracy and democratic socialism principally by its political decentralism rather than by its economics. The multi-tendency Socialist Party USA also has a strong libertarian socialist current.

Katja Kipping and Julia Bonk in Germany, Femke Halsema[236] in the Netherlands, and Ufuk Uras and the Freedom and Solidarity Party in Turkey are examples of contemporary libertarian socialist politicians and parties operating within mainstream parliamentary democracies. In Chile, the autonomist organization Izquierda Autónoma (Autonomous Left), in the 2013 Chilean general election, gained a seat in the Chilean Parliament through Gabriel Boric, ex-leader of the 2011–2013 Chilean student protests.[237] In 2016, Boric, alongside other persons such as Jorge Sharp, left the party to establish the Movimiento Autonomista.[238] In the Chilean municipal elections of October 2016, Sharp was elected Mayor of Valparaíso with a vote of 53%.[238][239] Currently in the United States, there is a caucus within the larger Democratic Socialists of America called the Libertarian Socialist Caucus: "The LSC promotes a vision of 'libertarian socialism'—a traditional name for anarchism—that goes beyond the confines of traditional social democratic politics".[240] In the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, Jacobin reports about the contemporary political party Candidatura d'Unitat Popular (CUP) as follows: