Turkey

Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye [ˈtyɾcije]), officially the Republic of Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti [ˈtyɾcije dʒumˈhuːɾijeti] (![]() listen)), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. It shares borders with the Black Sea to the north; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran to the east; Iraq to the southeast; Syria and the Mediterranean Sea to the south; the Aegean Sea to the west; and Greece and Bulgaria to the northwest. Cyprus is located off the south coast. Turks form the vast majority of the nation's population and Kurds are the largest minority.[4] Ankara is Turkey's capital, while Istanbul is its largest city and financial centre.

listen)), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. It shares borders with the Black Sea to the north; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran to the east; Iraq to the southeast; Syria and the Mediterranean Sea to the south; the Aegean Sea to the west; and Greece and Bulgaria to the northwest. Cyprus is located off the south coast. Turks form the vast majority of the nation's population and Kurds are the largest minority.[4] Ankara is Turkey's capital, while Istanbul is its largest city and financial centre.

Republic of Turkey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Anthem: İstiklal Marşı (Turkish) "The Independence March" | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Ankara 39°N 35°E |

| Largest city | Istanbul 41°1′N 28°57′E |

| Official languages | Turkish[1][2] |

| Spoken languages[3] |

|

| Other languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2016)[4] | |

| Religion | See Religion in Turkey |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

• President | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

• Vice President | Fuat Oktay |

• Assembly Speaker | Mustafa Şentop |

| Legislature | Grand National Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| c. 1299 | |

| 19 May 1919 | |

• Government of the Grand National Assembly | 23 April 1920 |

| 24 July 1923 | |

| 29 October 1923 | |

• Current constitution | 9 November 1982[5] |

| Area | |

• Total | 783,356 km2 (302,455 sq mi) (36th) |

• Water (%) | 2.03 (as of 2015)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 84,680,273[7] (18th) |

• Density | 110[8]/km2 (284.9/sq mi) (107th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 48th |

| Currency | Turkish lira (₺) (TRY) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +90 |

| ISO 3166 code | TR |

| Internet TLD | .tr |

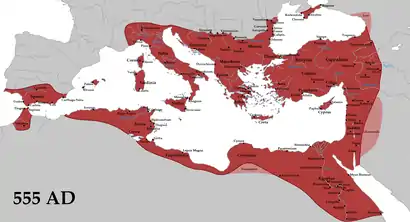

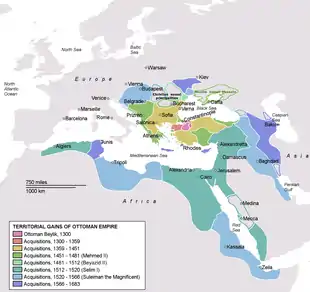

One of the world's earliest permanently settled regions, present-day Turkey was home to important Neolithic sites like Göbekli Tepe, and was inhabited by ancient civilisations including the Hattians, Hittites, Anatolian peoples, Mycenaean Greeks, Persians and others.[12][13][14][15] Following the conquests of Alexander the Great which started the Hellenistic period, most of the ancient regions in modern Turkey were culturally Hellenised, which continued during the Byzantine era.[13][16] The Seljuk Turks began migrating in the 11th century, and the Sultanate of Rum ruled Anatolia until the Mongol invasion in 1243, when it disintegrated into small Turkish principalities.[17] Beginning in the late 13th century, the Ottomans united the principalities and conquered the Balkans, and the Turkification of Anatolia increased during the Ottoman period. After Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1453, Ottoman expansion continued under Selim I. During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire became a global power.[12][18][19] From the late 18th century onwards, the empire's power declined with a gradual loss of territories.[20] Mahmud II started a period of modernisation in the early 19th century.[21] The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 restricted the authority of the Sultan and restored the Ottoman Parliament after a 30-year suspension, ushering the empire into a multi-party period.[22][23] The 1913 coup d'état put the country under the control of the Three Pashas, who facilitated the Empire's entry into World War I as part of the Central Powers in 1914. During the war, the Ottoman government committed genocides against its Armenian, Greek and Assyrian subjects.[lower-alpha 1][26] After its defeat in the war, the Ottoman Empire was partitioned.[27]

The Turkish War of Independence against the occupying Allied Powers resulted in the abolition of the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres) on 24 July 1923 and the proclamation of the Republic on 29 October 1923. With the reforms initiated by the country's first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey became a secular, unitary and parliamentary republic. Turkey played a prominent role in the Korean War and joined NATO in 1952. The country endured several military coups in the latter half of the 20th century. The economy was liberalised in the 1980s, leading to stronger economic growth and political stability. The parliamentary republic was replaced with a presidential system by referendum in 2017.

Turkey is a regional power and a newly industrialized country,[28] with a geopolitically strategic location.[29] Its economy, which is classified among the emerging and growth-leading economies, is the twentieth-largest in the world by nominal GDP, and the eleventh-largest by PPP. In addition to being an early member of NATO, Turkey is a charter member of the United Nations, the IMF, and the World Bank, and a founding member of the OECD, OSCE, BSEC, OIC, OTS and G20. After becoming one of the early members of the Council of Europe in 1950, Turkey became an associate member of the EEC in 1963, joined the EU Customs Union in 1995, and started accession negotiations with the European Union in 2005. Turkey has a rich cultural legacy shaped by centuries of history and the influence of the various peoples that have inhabited its territory over several millennia; it is home to 19 UNESCO World Heritage Sites and is among the most visited countries in the world.

Name

The English name of Turkey (from Medieval Latin Turchia/Turquia[30]) means "land of the Turks". Middle English usage of Turkye is evidenced in an early work by Chaucer called The Book of the Duchess (c. 1369). The phrase land of Torke is used in the 15th-century Digby Mysteries. Later usages can be found in the Dunbar poems, the 16th century Manipulus Vocabulorum (Turkie) and Francis Bacon's Sylva Sylvarum (Turky). The modern spelling Turkey dates back to at least 1719.[31]

The name of Turkey appeared in the Western sources after the crusades.[32] In the 14th-century Arab sources, turkiyya is usually contrasted with turkmaniyya (Turkomania), probably to be understood as Oghuz in a broad sense.[33] Ibn Battuta, in the 1330s introduces the region as barr al-Turkiyya al-ma'ruf bi-bilad al-Rum ("the Turkish land known as the lands of Rum").[34] The disintegration of the country after World War I revived Turkish nationalism, and the Türkler için Türkiye ("Turkey for the Turks") sentiment rose up. With the Treaty of Alexandropol signed by the Government of the Grand National Assembly with Armenia, the name of Türkiye entered international documents for the first time. In the treaty signed with Afghanistan, the expression Devlet-i Aliyye-i Türkiyye ("Sublime Turkish State") was used, likened to the Ottoman Empire's name.[32]

Official name change

In January 2020, the Turkish Exporters' Assembly (TİM) — the umbrella organisation of Turkish exports — announced that it would use "Made in Turkiye" on all its labels in a bid to standardise branding and the identity of Turkish businesses on the international stage, using the term 'Turkiye' across all languages around the world.[35]

In December 2021, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan issued a circular calling for exports to be labelled "Made in Türkiye". The circular also stated that in relation to other governmental communications "necessary sensitivity will be shown on the use of the phrase 'Türkiye' instead of phrases such as 'Turkey', 'Türkei', 'Turquie' etc."[36][37] The reason given in the circular for preferring Türkiye was that it "represents and expresses the culture, civilisation, and values of the Turkish nation in the best way". According to Turkish state broadcaster TRT World, it was also to avoid a pejorative association with turkey, the bird.[35] It was reported in January 2022 that the government planned to register Türkiye with the United Nations.[38] Minister of Foreign Affairs Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu sent letters to the UN and other international organisations on 31 May 2022 requesting that they use Türkiye. The UN agreed and implemented the request immediately.[39][40]

History

Prehistory of Anatolia and Eastern Thrace

The Anatolian peninsula, comprising most of modern Turkey, is one of the oldest permanently settled regions in the world. Various ancient Anatolian populations have lived in Anatolia, from at least the Neolithic until the Hellenistic period.[13] Many of these peoples spoke the Anatolian languages, a branch of the larger Indo-European language family:[42] and, given the antiquity of the Indo-European Hittite and Luwian languages, some scholars have proposed Anatolia as the hypothetical centre from which the Indo-European languages radiated.[43] The European part of Turkey, called Eastern Thrace, has also been inhabited since at least forty thousand years ago, and is known to have been in the Neolithic era by about 6000 BC.[14]

Göbekli Tepe is the site of the oldest known man-made religious structure, a temple dating to circa 10,000 BC,[41] while Çatalhöyük is a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from approximately 7500 BC to 5700 BC. It is the largest and best-preserved Neolithic site found to date and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[44] Nevalı Çori was an early Neolithic settlement on the middle Euphrates, in Şanlıurfa. Urfa Man statue is dated c. 9000 BC to the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, and is considered as "the oldest naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human".[45] It is considered as contemporaneous with the sites of Göbekli Tepe. The settlement of Troy started in the Neolithic Age and continued into the Iron Age.[46]

The earliest recorded inhabitants of Anatolia were the Hattians and Hurrians, non-Indo-European peoples who inhabited central and eastern Anatolia, respectively, as early as c. 2300 BC. Indo-European Hittites came to Anatolia and gradually absorbed the Hattians and Hurrians c. 2000–1700 BC. The first major empire in the area was founded by the Hittites, from the 18th through the 13th century BC. The Assyrians conquered and settled parts of southeastern Turkey as early as 1950 BC until the year 612 BC,[47] although they have remained a minority in the region, namely in Hakkari, Şırnak and Mardin.[48]

Urartu re-emerged in Assyrian inscriptions in the 9th century BC as a powerful northern rival of Assyria.[49] Following the collapse of the Hittite empire c. 1180 BC, the Phrygians, an Indo-European people, achieved ascendancy in Anatolia until their kingdom was destroyed by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BC.[50] Starting from 714 BC, Urartu shared the same fate and dissolved in 590 BC,[51] when it was conquered by the Medes. The most powerful of Phrygia's successor states were Lydia, Caria and Lycia.

Sardis was an ancient city at the location of modern Sart in Western Turkey. The city served as the capital of the ancient kingdom of Lydia. As one of the seven churches of Asia, it was addressed in the Book of Revelation in the New Testament,[52] The Lydian Lion coins were made of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver but of variable precious metal value. During the reign of King Croesus that the metallurgists of Sardis discovered the secret of separating gold from silver, thereby producing both metals of a purity never known before.[53]

Antiquity

Starting around 1200 BC, the coast of Anatolia was heavily settled by Aeolian and Ionian Greeks. Numerous important cities were founded by these colonists, such as Didyma, Miletus, Ephesus, Smyrna (now İzmir) and Byzantium (now Istanbul), the latter founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 657 BC.[54] Some of the most prominent pre-Socratic philosophers lived in the city of Miletus. Thales of Miletus (c. 624 BC – c. 546 BC) considered as first philosopher in the Greek tradition.[55][56] and he is otherwise historically recognized as the first individual known to have entertained and engaged in scientific philosophy.[57][58] In Miletus, he is followed by two other significant pre-Socratic philosophers Anaximander (c. 610 BC – c. 546 BC) and Anaximenes (c. 585 BC – c. 525 BC) (known collectively, to modern scholars, as the Milesian school).

For several centuries prior to the great Persian invasion of Greece, perhaps the very greatest and wealthiest city of the Greek world was Miletus, which founded more colonies than any other Greek city,[59] particularly in the Black Sea region. Diogenes the Cynic was one of the founders of Cynic philosophy born in one of the Ionian colonies Sinope on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia in 412.[60]

Trojan War took place in the ancient city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably Homer's Iliad. Whether there is any historical reality behind the Trojan War remains an open question. Those who believe that the stories of the Trojan War are derived from a specific historical conflict usually date it to the 12th or 11th century BC, often preferring the dates given by Eratosthenes, 1194–1184 BC, which roughly correspond to archaeological evidence of a catastrophic burning of Troy VII,[64] and the Late Bronze Age collapse.

The first state that was called Armenia by neighbouring peoples was the state of the Armenian Orontid dynasty, which included parts of what is now eastern Turkey beginning in the 6th century BC. In Northwest Turkey, the most significant tribal group in Thrace was the Odyrisians, founded by Teres I.[65]

All of modern-day Turkey was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire during the 6th century BC.[66] The Greco-Persian Wars started when the Greek city states on the coast of Anatolia rebelled against Persian rule in 499 BC.

Artemisia I of Caria was a queen of the ancient Greek city-state of Halicarnassus and she fought as an ally of Xerxes I, King of Persia against the independent Greek city states during the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC.[67][68]

The territory of Turkey later fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BC,[69] which led to increasing cultural homogeneity and Hellenization in the area.[13] Following Alexander's death in 323 BC, Anatolia was subsequently divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms, all of which became part of the Roman Republic by the mid-1st century BC.[70] The process of Hellenization that began with Alexander's conquest accelerated under Roman rule, and by the early centuries of the Christian Era, the local Anatolian languages and cultures had become extinct, being largely replaced by ancient Greek language and culture.[16][71] From the 1st century BC up to the 3rd century AD, large parts of modern-day Turkey were contested between the Romans and neighbouring Parthians through the frequent Roman-Parthian Wars.

Galatia was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia inhabited by the Celts. The terms "Galatians" came to be used by the Greeks for the three Celtic peoples of Anatolia: the Tectosages, the Trocmii, and the Tolistobogii.[72][73] By the 1st century BC the Celts had become so Hellenized that some Greek writers called them Hellenogalatai (Ἑλληνογαλάται).[74] Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (cf. Tylis), who settled here and became a small transient foreign tribe in the 3rd century BC, following the supposed Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC.

Kingdom of Pontus was a Hellenistic kingdom, centered in the historical region of Pontus and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty of Persian origin,[75][76][77][78] which may have been directly related to Darius the Great and the Achaemenid dynasty.[79][78] The kingdom was proclaimed by Mithridates I in 281 BC and lasted until its conquest by the Roman Republic in 63 BC. The Kingdom of Pontus reached its largest extent under Mithridates VI the Great, who conquered Colchis, Cappadocia, Bithynia, the Greek colonies of the Tauric Chersonesos. After a long struggle with Rome in the Mithridatic Wars, Pontus was defeated.

All territories corresponding to modern Turkey eventually fell into Roman Empire’s control.

Early Christian and Roman period

.jpg.webp)

According to the Acts of Apostles,[81] Antioch (now Antakya), a city in southern Turkey, is where followers of Jesus were first called "Christians" and became very quickly an important center of Christianity.[82][83] Paul the Apostle traveled to Ephesus and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker.[84] He is claimed to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.[85] Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-Artemis riot involving most of the city.[85]

In the year 123, Emperor Hadrian traveled to Anatolia. Numerous monuments were erected for his arrival and he met his lover Antinous from Bithynia.[86] Hadrian focused on the Greek revival and built several temples and improved the cities. Cyzicus, Pergamon, Smyrna, Ephesus and Sardes were promoted as regional centres for the Imperial cult (neocoros) during this period.[87]

Byzantine period

In 324 AD, Constantine I chose Byzantium to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, renaming it New Rome. Under Constantine, Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the state, but enjoyed imperial preference since he supported it with generous privileges. Following the death of Theodosius I in 395 and the permanent division of the Roman Empire between his two sons, the city, which would popularly come to be known as Constantinople, became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. This empire, which would later be branded by historians as the Byzantine Empire, ruled most of the territory of present-day Turkey until the Late Middle Ages;[88] although the eastern regions remained firmly in Sasanian hands until the first half of the 7th century. The frequent Byzantine-Sassanid Wars, a continuation of the centuries-long Roman-Persian Wars, took place in various parts of present-day Turkey between the 4th and 7th centuries. Several ecumenical councils of the early Church were held in cities located in present-day Turkey, including the First Council of Nicaea (Iznik) in 325, the First Council of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, and the Council of Chalcedon (Kadıköy) in 451.[89] During most of its existence, the Byzantine Empire was one of the most powerful economic, cultural, and military forces in Europe.[90]

Seljuks and the Ottoman Empire

The House of Seljuk originated from the Kınık branch of the Oghuz Turks who resided on the periphery of the Muslim world, in the Yabgu Khaganate of the Oğuz confederacy, to the north of the Caspian and Aral Seas, in the 9th century.[91] In the 10th century, the Seljuks started migrating from their ancestral homeland into Persia, which became the administrative core of the Great Seljuk Empire, after its foundation by Tughril.[92]

In the latter half of the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks began penetrating into medieval Armenia and the eastern regions of Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert, starting the Turkification process in the area; the Turkish language and Islam were introduced to Anatolia, gradually spreading throughout the region. The slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway. The Mevlevi Order of dervishes, which was established in Konya during the 13th century by Sufi poet Celaleddin Rumi, played a significant role in the Islamization of the diverse people of Anatolia who had previously been Hellenized.[94][95] Thus, alongside the Turkification of the territory, the culturally Persianized Seljuks set the basis for a Turko-Persian principal culture in Anatolia,[96] which their eventual successors, the Ottomans, would take over.[97][98] In 1243, the Seljuk armies were defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Köse Dağ, causing the Seljuk Empire's power to slowly disintegrate. In its wake, one of the Turkish principalities governed by Osman I would evolve over the next 200 years into the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans completed their conquest of the Byzantine Empire by capturing its capital, Constantinople, in 1453: their commander thenceforth being known as Mehmed the Conqueror.

In 1514, Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) successfully expanded the empire's southern and eastern borders by defeating Shah Ismail I of the Safavid dynasty in the Battle of Chaldiran. In 1517, Selim I expanded Ottoman rule into Algeria and Egypt, and created a naval presence in the Red Sea. Subsequently, a contest started between the Ottoman and Portuguese empires to become the dominant sea power in the Indian Ocean, with a number of naval battles in the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf. The Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean was perceived as a threat to the Ottoman monopoly over the ancient trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe. Despite the increasingly prominent European presence, the Ottoman Empire's trade with the east continued to flourish until the second half of the 18th century.[101]

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, who personally instituted major legislative changes relating to society, education, taxation and criminal law.

The empire was often at odds with the Holy Roman Empire in its steady advance towards Central Europe through the Balkans and the southern part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[102]

The Ottoman Navy contended with several Holy Leagues, such as those in 1538, 1571, 1684 and 1717 (composed primarily of Habsburg Spain, the Republic of Genoa, the Republic of Venice, the Knights of St. John, the Papal States, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchy of Savoy), for the control of the Mediterranean Sea.

In the east, the Ottomans were often at war with Safavid Persia over conflicts stemming from territorial disputes or religious differences between the 16th and 18th centuries.[103] The Ottoman wars with Persia continued as the Zand, Afsharid, and Qajar dynasties succeeded the Safavids in Iran, until the first half of the 19th century.

Even further east, there was an extension of the Habsburg-Ottoman conflict, in that the Ottomans also had to send soldiers to their farthest and easternmost vassal and territory, the Aceh Sultanate[104][105] in Southeast Asia, to defend it from European colonizers as well as the Latino invaders who had crossed from Latin America and had Christianized the formerly Muslim-dominated Philippines.[106]

From the 16th to the early 20th centuries, the Ottoman Empire also fought twelve wars with the Russian Tsardom and Empire. These were initially about Ottoman territorial expansion and consolidation in southeastern and eastern Europe; but starting from the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), they became more about the survival of the Ottoman Empire, which had begun to lose its strategic territories on the northern Black Sea coast to the advancing Russians.

From the second half of the 18th century onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to decline. The Tanzimat reforms, initiated by Mahmud II just before his death in 1839, aimed to modernise the Ottoman state in line with the progress that had been made in Western Europe. The efforts of Midhat Pasha during the late Tanzimat era led the Ottoman constitutional movement of 1876, which introduced the First Constitutional Era, but these efforts proved to be inadequate in most fields, and failed to stop the dissolution of the empire.[107]

As the empire gradually shrank in size, military power and wealth; especially after the Ottoman economic crisis and default in 1875[108] which led to uprisings in the Balkan provinces that culminated in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878); many Balkan Muslims migrated to the Empire's heartland in Anatolia,[109][110] along with the Circassians fleeing the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. According to some estimates, up to 1.5 million Muslim Circassians died during the Circassian genocide, the survivors seek refugee in Ottoman Empire. The decline of the Ottoman Empire led to a rise in nationalist sentiment among its various subject peoples, leading to increased ethnic tensions which occasionally burst into violence, such as the Hamidian massacres of Armenians, which claimed up to 300,000 lives.[111]

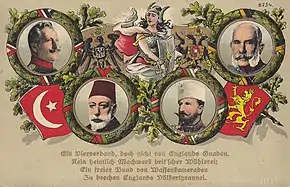

- Central Power Monarchs on a WWI Postcard:

- Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany;

- Kaiser and King Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary;

- Sultan Mehmed V of the Ottoman Empire;

- Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria

The loss of Rumelia (Ottoman territories in Europe) with the First Balkan War (1912–1913) was followed by the arrival of millions of Muslim refugees (muhacir) to Istanbul and Anatolia.[112] Historically, the Rumelia Eyalet and Anatolia Eyalet had formed the administrative core of the Ottoman Empire, with their governors titled Beylerbeyi participating in the Sultan's Divan, so the loss of all Balkan provinces beyond the Midye-Enez border line according to the London Conference of 1912–13 and the Treaty of London (1913) was a major shock for the Ottoman society and led to the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état. In the Second Balkan War (1913) the Ottomans managed to recover their former capital Edirne (Adrianople) and its surrounding areas in East Thrace, which was formalised with the Treaty of Constantinople (1913). The 1913 coup d'état effectively put the country under the control of the Three Pashas, making sultans Mehmed V and Mehmed VI largely symbolic figureheads with no real political power.

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The Ottomans successfully defended the Dardanelles strait during the Gallipoli campaign (1915–1916) and achieved initial victories against British forces in the first two years of the Mesopotamian campaign, such as the Siege of Kut (1915–1916); but the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) turned the tide against the Ottomans in the Middle East. In the Caucasus campaign, however, the Russian forces had the upper hand from the beginning, especially after the Battle of Sarikamish (1914–1915). Russian forces advanced into northeastern Anatolia and controlled the major cities there until retreating from World War I with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk following the Russian Revolution (1917). During the war, the empire's Armenian subjects were deported to Syria as part of the Armenian genocide. As a result, an estimated 600,000[113] to more than 1 million,[113] or up to 1.5 million[114][115][116] Armenians were killed. The Turkish government has refused to acknowledge the events as genocide and states that Armenians were only "relocated" from the eastern war zone.[117] Genocidal campaigns were also committed against the empire's other minority groups such as the Assyrians and Greeks.[118][119][120] Following the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918, the victorious Allied Powers sought to partition the Ottoman state through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.[121]

Republic of Turkey

The occupation of Istanbul (1918) and İzmir (1919) by the Allies in the aftermath of World War I prompted the establishment of the Turkish National Movement. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920).[122]

By 18 September 1922 the Greek, Armenian and French armies had been expelled,[123] and the Turkish Provisional Government in Ankara, which had declared itself the legitimate government of the country on 23 April 1920, started to formalise the legal transition from the old Ottoman into the new Republican political system. On 1 November 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate, thus ending 623 years of monarchical Ottoman rule. The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres,[121][122] led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the newly formed "Republic of Turkey" as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, and the republic was officially proclaimed on 29 October 1923 in Ankara, the country's new capital.[124] The Lausanne Convention stipulated a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, whereby 1.1 million Greeks left Turkey for Greece in exchange for 380,000 Muslims transferred from Greece to Turkey.[125]

.jpg.webp)

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first President and subsequently introduced many reforms. The reforms aimed to transform the old religion-based and multi-communal Ottoman constitutional monarchy into a Turkish nation state that would be governed as a parliamentary republic under a secular constitution.[127] With the Surname Law of 1934, the Turkish Parliament bestowed upon Mustafa Kemal the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father Turk).[122]

The Montreux Convention (1936) restored Turkey's control over the Turkish Straits, including the right to militarise the coastlines of the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits and the Sea of Marmara, and to block maritime traffic in wartime.[128]

Following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, some Kurdish and Zaza tribes, which were feudal (manorial) communities led by chieftains (agha) during the Ottoman period, became discontent about certain aspects of Atatürk's reforms aiming to modernise the country, such as secularism (the Sheikh Said rebellion, 1925)[129] and land reform (the Dersim rebellion, 1937–1938),[130] and staged armed revolts that were put down with military operations.

İsmet İnönü became Turkey's second President following Atatürk's death on 10 November 1938. On 29 June 1939, the Republic of Hatay voted in favour of joining Turkey with a referendum. Turkey remained neutral during most of World War II, but entered the closing stages of the war on the side of the Allies on 23 February 1945. On 26 June 1945, Turkey became a charter member of the United Nations.[131] In the following year, the one-party period in Turkey came to an end, with the first multi-party elections in 1946. In 1950 Turkey became a member of the Council of Europe.

The Democrat Party established by Celâl Bayar won the 1950, 1954 and 1957 general elections and stayed in power for a decade, with Adnan Menderes as the Prime Minister and Bayar as the President. After fighting as part of the United Nations forces in the Korean War, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, becoming a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean. Turkey subsequently became a founding member of the OECD in 1961, and an associate member of the EEC in 1963.[132]

The country's tumultuous transition to multi-party democracy was interrupted by military coups d'état in 1960 and 1980, as well as by military memorandums in 1971 and 1997.[133][134] Between 1960 and the end of the 20th century, the prominent leaders in Turkish politics who achieved multiple election victories were Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit and Turgut Özal. Tansu Çiller became the first female prime minister of Turkey in 1993.

Following a decade of Cypriot intercommunal violence and the coup in Cyprus on 15 July 1974 staged by the EOKA B paramilitary organisation, which overthrew President Makarios and installed the pro-Enosis (union with Greece) Nikos Sampson as dictator, Turkey invaded Cyprus on 20 July 1974 by unilaterally exercising Article IV in the Treaty of Guarantee (1960), but without restoring the status quo ante at the end of the military operation.[135] In 1983 the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is recognised only by Turkey, was established.[136] The Annan Plan for reunifying the island was supported by the majority of Turkish Cypriots, but rejected by the majority of Greek Cypriots, in separate referendums in 2004. However, negotiations for solving the Cyprus dispute are still ongoing between Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot political leaders.[137]

The conflict between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) (designated a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the United States,[138] and the European Union[139]) has been active since 1984, primarily in the southeast of the country. More than 40,000 people have died as a result of the conflict.[140][141][142] In 1999 PKK's founder Abdullah Öcalan was arrested and sentenced for terrorism[138][139] and treason charges.[143][144] In the past, various Kurdish groups have unsuccessfully sought separation from Turkey to create an independent Kurdish state, while others have more recently pursued provincial autonomy and greater political and cultural rights for Kurds in Turkey. In the 21st century some reforms have taken place to improve the cultural rights of ethnic minorities in Turkey, such as the establishment of TRT Kurdî, TRT Arabi and TRT Avaz by the TRT.

Since the liberalisation of the Turkish economy in the 1980s, the country has enjoyed stronger economic growth and greater political stability.[145] Turkey applied for full membership of the EEC in 1987, joined the EU Customs Union in 1995 and started accession negotiations with the European Union in 2005.[146][147] In a non-binding vote on 13 March 2019, the European Parliament called on the EU governments to suspend EU accession talks with Turkey, citing violations of human rights and the rule of law; but the negotiations, effectively on hold since 2018, remain active as of 2020.[148]

In 2013, widespread protests erupted in many Turkish provinces, sparked by a plan to demolish Gezi Park but soon growing into general anti-government dissent.[149] On 15 July 2016, an unsuccessful coup attempt tried to oust the government.[150] As a reaction to the failed coup d'état, the government carried out mass purges,[151][152] jailed journalists, and shut down media outlets.[153]

Between 9 October and 25 November 2019, Turkey invaded north-eastern Syria.[154][155][156]

Administrative divisions

Turkey has a unitary structure in terms of administration and this aspect is one of the most important factors shaping the Turkish public administration. When three powers (executive, legislative and judiciary) are taken into account as the main functions of the state, local administrations have little power. Turkey does not have a federal system, and the provinces are subordinate to the central government in Ankara. Local administrations were established to provide services in place and the government is represented by the province governors (vali) and town governors (kaymakam). Other senior public officials are also appointed by the central government instead of the mayors (belediye başkanı) or elected by constituents.[157] Turkish municipalities have local legislative bodies (belediye meclisi) for decision-making on municipal issues.

Within this unitary framework, Turkey is subdivided into 81 provinces (il or vilayet) for administrative purposes. Each province is divided into districts (ilçe), for a total of 973 districts.[158] Turkey is also subdivided into 7 regions (bölge) and 21 subregions for geographic, demographic and economic purposes; this does not refer to an administrative division.

Government and politics

Turkey is a presidential republic within a multi-party system.[159] The current constitution was approved by referendum in 1982, which determines the government's structure, lays forth the ideals and standards of the state's conduct, and sets out the state's responsibility to its citizens. Furthermore, the constitution specifies the people's rights and obligations, as well as principles for the delegation and exercise of sovereignty that belongs to the people of Turkey.[160]

In the Turkish unitary system, citizens are subject to three levels of government: national, provincial, and local. The local government's duties are commonly split between municipal governments and districts, in which executive and legislative officials are elected by a plurality vote of citizens by district. Turkey is subdivided into 81 provinces for administrative purposes. Each province is divided into districts, for a total of 973 districts.

The government, regulated by a system of separation of powers as defined by the constitution of Turkey, comprises three branches:

- Legislative: The unicameral Parliament makes law, debates and adopts the budget bills, declares war, approves treaties, proclaims amnesty and pardon, and has the power of impeachment, by which it can remove sitting members of the government.[161]

- Executive: The president is the commander-in-chief of the military, can veto legislative bills before they become law (subject to parliamentary override), can issue presidential decrees on matters regarding executive power with exception of fundamental rights, individual rights and certain political rights (parliamentary laws prevail presidential decrees), and appoints the members of the Cabinet and other officers, who administer and enforce national laws and policies.[162]

- Judicial: The Constitutional Court (for constitutional adjudication and review of individual applications concerning human rights), the Court of Cassation (final decision maker in ordinary judiciary), the Council of State (final decision maker in administrative judiciary) and the Court of Jurisdictional Disputes (for resolving the disputes between courts for constitutional jurisdiction) are the four organizations that are described by the Constitution as supreme courts. The judges of the Constitutional Court are appointed by the president and the parliament.[5]

The Parliament has 600 voting members, each representing a constituency for a five-year term. Parliamentary seats are distributed among the provinces by population, conform with the census apportionment. The president is elected by direct vote and serves a five-year term. The president can't run for re-elections after two terms of five-years, unless parliament prematurely renews the presidential elections during the second term of the President. Elections for the Parliament and presidential elections are held on the same day. The Constitutional Court is composed of fifteen members. A member is elected for a term of twelve years and can't be reelected. The members of the Constitutional Court are obliged to retire when they are over the age of sixty-five.[163]

Parties and elections

President

Elections in Turkey are held for six functions of government: presidential elections (national), parliamentary elections (national), municipality mayors (local), district mayors (local), provincial or municipal council members (local) and muhtars (local). Apart from elections, referendums are also held occasionally.

Every Turkish citizen who has turned 18 has the right to vote and stand as a candidate at elections. Universal suffrage for both sexes has been applied throughout Turkey since 1934 and before most countries. In Turkey, turnout rates of both local and general elections are high compared to many other countries, which usually stands higher than 80 percent.[164] There are 600 members of parliament who are elected for a five-year term by a party-list proportional representation system from 88 electoral districts. The Constitutional Court can strip the public financing of political parties that it deems anti-secular or having ties to terrorism, or ban their existence altogether.[165][166] The electoral threshold for political parties at national level is seven percent of the votes.[167] Smaller parties can avoid the electoral threshold by forming an alliance with other parties, in which it is sufficient that the total votes of the alliance passes 7%. Independent candidates are not subject to an electoral threshold.

After World War II, Turkey operated under a multi-party system. On the right side of the Turkish political spectrum, parties like Democrat Party (DP), Justice Party (AP), Motherland Party (ANAP) and Justice and Development Party (AKP) once became the largest political party in Turkey. Turkish right-wing parties are more likely to embrace principles of political ideologies such as conservatism, nationalism or Islamism.[168] On the left side of the spectrum, parties like Republican People's Party (CHP), Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP) and Democratic Left Party (DSP) once enjoyed the largest electoral success. Left-wing parties are more likely to embrace principles of socialism, Kemalism or secularism.[169]

The 12th President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the winner of the 2018 presidential election and former prime minister, is currently serving as the head of state and head of government. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu is the main opposition leader of Turkey. Mustafa Şentop is the Speaker of the Grand National Assembly.

The 27th Parliament of Turkey was installed following the 2018 parliamentary election, with the starting composition of 295 seats for the Justice and Development Party (AKP), 146 seats for the Republican People's Party (CHP), 67 seats for the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), 49 seats for the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and 49 seats for the Good Party (İP).[170] The next parliamentary election is scheduled to take place in 2023.

Law

.jpg.webp)

With the founding of the Republic, Turkey adopted a civil law legal system, replacing Sharia-derived Ottoman law. The Civil Code, adopted in 1926, was based on the Swiss Civil Code of 1907 and the Swiss Code of Obligations of 1911. Although it underwent a number of changes in 2002, it retains much of the basis of the original Code. The Criminal Code, originally based on the Italian Criminal Code, was replaced in 2005 by a Code with principles similar to the German Penal Code and German law generally. Administrative law is based on the French equivalent and procedural law generally shows the influence of the Swiss, German and French legal systems.[171] Islamic principles do not play a part in the legal system.[172]

Turkey has adopted the principle of the separation of powers. In line with this principle, judicial power is exercised by independent courts on behalf of the Turkish nation. The independence and organisation of the courts, the security of the tenure of judges and public prosecutors, the profession of judges and prosecutors, the supervision of judges and public prosecutors, the military courts and their organisation, and the powers and duties of the high courts are regulated by the Turkish Constitution.[173]

According to Article 142 of the Turkish Constitution, the organisation, duties and jurisdiction of the courts, their functions and the trial procedures are regulated by law. In line with the aforementioned article of the Turkish Constitution and related laws, the court system in Turkey can be classified under three main categories; which are the Judicial Courts, Administrative Courts, and Military Courts. Each category includes first instance courts and high courts. In addition, the Court of Jurisdictional Disputes rules on cases that cannot be classified readily as falling within the purview of one court system.[173]

Law enforcement in Turkey is carried out by several agencies under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. These agencies are the General Directorate of Security, the Gendarmerie General Command and the Coast Guard Command. Furthermore, there are other law enforcement agencies with specific (National Intelligence Organization, General Directorate of Customs Protection, etc.) or local (Village guards, Municipal Police, etc.) assignments that are under the jurisdiction of the president or different ministries.

In the years of government by the AKP and Erdoğan, particularly since 2013, the independence and integrity of the Turkish judiciary has increasingly been said to be in doubt by institutions, parliamentarians and journalists both within and outside of Turkey; due to political interference in the promotion of judges and prosecutors, and in their pursuit of public duty.[174][175][176][177] The Turkey 2015 report of the European Commission stated that "the independence of the judiciary and respect of the principle of separation of powers have been undermined and judges and prosecutors have been under strong political pressure."[174]

Foreign relations

Turkey is a founding member of the United Nations (1945),[178] the OECD (1961),[179] the OIC (1969),[180] the OSCE (1973),[181] the ECO (1985),[182] the BSEC (1992),[183] the D-8 (1997)[184] and the G20 (1999).[185] Turkey was a member of the United Nations Security Council in 1951–1952, 1954–1955, 1961 and 2009–2010.[186] In 2012 Turkey became a dialogue partner of the SCO, and in 2013 became a member of the ACD.[187][188]

In line with its traditional Western orientation, relations with Europe have always been a central part of Turkish foreign policy. Turkey became one of the early members of the Council of Europe in 1950, applied for associate membership of the EEC (predecessor of the European Union) in 1959 and became an associate member in 1963. After decades of political negotiations, Turkey applied for full membership of the EEC in 1987, became an associate member of the Western European Union in 1992, joined the EU Customs Union in 1995 and has been in formal accession negotiations with the EU since 2005.[146][147] Turkey's support for Northern Cyprus in the Cyprus dispute complicates Turkey's relations with the EU and remains a major stumbling block to the country's EU accession bid.[189]

The other defining aspect of Turkey's foreign policy was the country's long-standing strategic alliance with the United States.[190][191] The Truman Doctrine in 1947 enunciated American intentions to guarantee the security of Turkey and Greece during the Cold War, and resulted in large-scale U.S. military and economic support. In 1948 both countries were included in the Marshall Plan and the OEEC for rebuilding European economies.[192] The common threat posed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War led to Turkey's membership of NATO in 1952, ensuring close bilateral relations with the US. Subsequently, Turkey benefited from the United States' political, economic and diplomatic support, including in key issues such as the country's bid to join the European Union.[193] In the post–Cold War environment, Turkey's geostrategic importance shifted towards its proximity to the Middle East, the Caucasus and the Balkans.[194]

.jpg.webp)

The independence of the Turkic states of the Soviet Union in 1991, with which Turkey shares a common cultural and linguistic heritage, allowed Turkey to extend its economic and political relations deep into Central Asia,[196] thus enabling the completion of a multi-billion-dollar oil and natural gas pipeline from Baku in Azerbaijan to the port of Ceyhan in Turkey. The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline forms part of Turkey's foreign policy strategy to become an energy conduit from the Caspian Sea basin to Europe. However, in 1993, Turkey sealed its land border with Armenia in a gesture of support to Azerbaijan (a Turkic state in the Caucasus region) during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, and it remains closed.[197] Armenia and Turkey started diplomatic talks in order to normalise the relationship between the two countries. The discussions include opening the closed borders and starting trade. Turkey and Armenia have also restarted commercial flights between the two countries.[198]

Under the AKP government, Turkey's influence has grown in the formerly Ottoman territories of the Middle East and the Balkans, based on the "strategic depth" doctrine (a terminology that was coined by Ahmet Davutoğlu for defining Turkey's increased engagement in regional foreign policy issues), also called Neo-Ottomanism.[199][200] Following the Arab Spring in December 2010, the choices made by the AKP government for supporting certain political opposition groups in the affected countries have led to tensions with some Arab states, such as Turkey's neighbour Syria since the start of the Syrian civil war, and Egypt after the ousting of President Mohamed Morsi.[201][202]

As of 2021, Turkey does not have an ambassador in either Syria or Egypt.[203] Diplomatic relations with Israel were also severed after the Gaza flotilla raid in 2010, but were normalised following a deal in June 2016.[204] These political rifts have left Turkey with few allies in the East Mediterranean, where rich natural gas fields have recently been discovered;[205][206] in sharp contrast with the original goals that were set by the former Foreign Minister (later Prime Minister) Ahmet Davutoğlu in his "zero problems with neighbours"[207][208] foreign policy doctrine.[209] In 2015, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar formed a "strategic alliance" against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.[210] However, following the rapprochement with Russia in 2016, Turkey revised its stance regarding the solution of the conflict in Syria.[211][212][213] In January 2018, the Turkish military and the Turkish-backed forces, including the Free Syrian Army and Ahrar al-Sham,[214] began an intervention in Syria aimed at ousting U.S.-backed YPG from the enclave of Afrin.[215][216] There is a dispute over Turkey's maritime boundaries with Greece and Cyprus and drilling rights in the eastern Mediterranean.[217][218]

Military

The Turkish Armed Forces consist of the General Staff, the Land Forces, the Naval Forces and the Air Force. The Chief of the General Staff is appointed by the President. President is responsible to the Parliament for matters of national security and the adequate preparation of the armed forces to defend the country. However, the authority to declare war and to deploy the Turkish Armed Forces to foreign countries or to allow foreign armed forces to be stationed in Turkey rests solely with the Parliament.[219]

The Gendarmerie General Command and the Coast Guard Command are law enforcement agencies with military organization (ranks, structure, etc.) and under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior. In wartime, the president can order certain units of the Gendarmerie General Command and the Coast Guard Command to operate under the Land Forces Command and Naval Forces Commands respectively. The remaining parts of the Gendarmerie and the Coast Guard continue to carry out their law enforcement missions under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior.

Every fit male Turkish citizen otherwise not barred is required to serve in the military for a period ranging from three weeks to a year, dependent on education and job location.[220] Turkey does not recognise conscientious objection and does not offer a civilian alternative to military service.[221]

Turkey has the second-largest standing military force in NATO, after the United States, with an estimated strength of 890,700 military as of February 2022.[222] Turkey is one of five NATO member states which are part of the nuclear sharing policy of the alliance, together with Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.[223] A total of 90 B61 nuclear bombs are hosted at the Incirlik Air Base, 40 of which are allocated for use by the Turkish Air Force in case of a nuclear conflict, but their use requires the approval of NATO.[224]

Turkey has participated in international missions under the United Nations and NATO since the Korean War, including peacekeeping missions in Somalia, Yugoslavia and the Horn of Africa. It supported coalition forces in the First Gulf War, contributed military personnel to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, and remains active in Kosovo Force, Eurocorps and EU Battlegroups.[225][226] In recent years, Turkey has assisted Peshmerga forces in northern Iraq and the Somali Armed Forces with security and training.[227][228] Turkish Armed Forces have a relatively substantial military presence abroad,[229] with military bases in Albania,[230] Iraq,[231] Qatar,[232] and Somalia.[233] The country also maintains a force of 36,000 troops in Northern Cyprus since 1974.[234]

Human rights

The human rights record of Turkey has been the subject of much controversy and international condemnation. Between 1959 and 2011 the European Court of Human Rights made more than 2400 judgements against Turkey for human rights violations on issues such as Kurdish rights, women's rights, LGBT rights, and media freedom.[235][236] Turkey's human rights record continues to be a significant obstacle to the country's membership of the EU.[237]

In the latter half of the 1970s, Turkey suffered from political violence between far-left and far-right militant groups, which culminated in the military coup of 1980.[238] The Kurdistan Workers' Party - a.k.a. PKK - (designated a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the United States,[138] and the European Union[139]) was founded in 1978 by a group of Kurdish militants led by Abdullah Öcalan, seeking the foundation of an independent Kurdish state based on Marxist-Leninist ideology.[239] The initial reason given by the PKK for this was the oppression of Kurds in Turkey.[240][241] A full-scale insurgency began in 1984, when the PKK announced a Kurdish uprising. With time the PKK modified its demands into equal rights for ethnic Kurds and provincial autonomy within Turkey.[242][243][244][245] Since 1980, the Turkish parliament stripped its members of immunity from prosecution, including 44 deputies most of which from the pro-Kurdish parties.[246]

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the AKP government has waged crackdowns on media freedom.[247][248] Many journalists have been arrested using charges of "terrorism" and "anti-state activities". In 2020, the CPJ identified 18 jailed journalists in Turkey (including the editorial staff of Cumhuriyet, Turkey's oldest newspaper still in circulation), all directly held for their published work; [249] while in 2020 Freemuse identified seven musicians imprisoned for their work. Some of which for promoting drug use in their lyrics.[250] [251]

LGBT rights

Homosexual activity is legal in Turkey since 1858.[253] LGBT people have had the right to seek asylum in Turkey under the Geneva Convention since 1951.[254] However, LGBT people in Turkey face discrimination, harassment and even violence from their relatives, neighbors, etc.[255] The Turkish authorities have carried out many discriminatory practices.[256][257][258] Despite these, LGBT acceptance in Turkey is growing. In a survey conducted by Kadir Has University in Istanbul in 2016, 33% of respondents said that LGBT people should have equal rights, which increased to 45% in 2020. Another survey by Kadir Has University in 2018 found that the proportion of people who would not want a homosexual neighbour decreased from 55% in 2018 to 47% in 2019.[259][260] A poll by Ipsos in 2015 found that 27% of the Turkish public was in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage and 19% supported civil unions instead.[261]

Istanbul Pride was held for the first time in 2003. Turkey became the first Muslim-majority country to hold a gay pride march.[262]

Geography

Turkey is a transcontinental country bridging Southeastern Europe and Western Asia. Asian Turkey, which includes 97 percent of the country's territory, is separated from European Turkey by the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles. European Turkey comprises only 3 percent of the country's territory.[263] Turkey covers an area of 783,562 square kilometres (302,535 square miles),[264] of which 755,688 square kilometres (291,773 square miles) is in Asia and 23,764 square kilometres (9,175 square miles) is in Europe.[265] The country is encircled by seas on three sides: the Aegean Sea to the west, the Black Sea to the north and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. Turkey also contains the Sea of Marmara in the northwest.[266]

Turkey is divided into seven geographical regions: Marmara, Aegean, Black Sea, Central Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia and the Mediterranean. The uneven north Anatolian terrain running along the Black Sea resembles a long, narrow belt. This region comprises approximately one-sixth of Turkey's total land area. As a general trend, the inland Anatolian plateau becomes increasingly rugged as it progresses eastward.[266] Pamukkale terraces are made of travertine, a sedimentary rock deposited by mineral water from the hot springs. The area is famous for a carbonate mineral left by the flowing of thermal spring water.[267][268] It is located in Turkey's Inner Aegean region, in the River Menderes valley, which has a temperate climate for most of the year. It was added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988 with Hierapolis.

East Thrace; the European portion of Turkey, is located at the easternmost edge the Balkans. It forms the border between Turkey and its neighbours Greece and Bulgaria. The Asian part of the country mostly consists of the peninsula of Anatolia, which consists of a high central plateau with narrow coastal plains, between the Köroğlu and Pontic mountain ranges to the north and the Taurus Mountains to the south.

The Eastern Anatolia Region mostly corresponds to the western part of the Armenian Highlands (the plateau situated between the Anatolian Plateau in the west and the Lesser Caucasus in the north)[269] and contains Mount Ararat, Turkey's highest point at 5,137 metres (16,854 feet),[270] and Lake Van, the largest lake in the country.[271] Eastern Turkey has a mountainous landscape and is home to the sources of rivers such as the Euphrates, Tigris and Aras. The Southeastern Anatolia Region includes the northern plains of Upper Mesopotamia.

Far from the coast the climate of Turkey tends to be continental but elsewhere temperate, and has become hotter, and drier in parts. There are many species of plants and animals.

Biodiversity

Turkey's extraordinary ecosystem and habitat diversity has produced considerable species diversity.[272] Anatolia is the homeland of many plants that have been cultivated for food since the advent of agriculture, and the wild ancestors of many plants that now provide staples for humankind still grow in Turkey. The diversity of Turkey's fauna is even greater than that of its flora. The number of animal species in the whole of Europe is around 60,000, while in Turkey there are over 80,000 (over 100,000 counting the subspecies).[273]

The Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests is an ecoregion which covers most of the Pontic Mountains in northern Turkey, while the Caucasus mixed forests extend across the eastern end of the range. The region is home to Eurasian wildlife such as the Eurasian sparrowhawk, golden eagle, eastern imperial eagle, lesser spotted eagle, Caucasian black grouse, red-fronted serin, and wallcreeper.[274] The narrow coastal strip between the Pontic Mountains and the Black Sea is home to the Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests, which contain some of the world's few temperate rainforests.[275] The Turkish pine (Pinus brutia) is mostly found in Turkey and other east Mediterranean countries; the other commonly found species of the genus Pinus (pine) in Turkey include the nigra, sylvestris, pinea and halepensis. The Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and numerous other species of the genus Quercus (oak) exist in Turkey. The most commonly found species of the genus Platanus (plane) is the orientalis. Several wild species of tulip are native to Anatolia, and the flower was first introduced to Western Europe with species taken from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.[276][277]

There are 40 national parks, 189 nature parks, 31 nature preserve areas, 80 wildlife protection areas and 109 nature monuments in Turkey such as Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park, Mount Nemrut National Park, Ancient Troy National Park, Ölüdeniz Nature Park and Polonezköy Nature Park.[278] In the 21st century, threats to biodiversity include desertification due to climate change in Turkey.[279]

The Anatolian leopard is still found in very small numbers in the northeastern and southeastern regions of Turkey.[280][281] The Eurasian lynx and the European wildcat are other felid species which are currently found in the forests of Turkey. The Caspian tiger, now extinct, lived in the easternmost regions of Turkey until the latter half of the 20th century.[280][282]

Renowned domestic animals from Ankara, the capital of Turkey, include the Angora cat, Angora rabbit and Angora goat; and from Van Province the Van cat. The national dog breeds are the Kangal (Anatolian Shepherd), Malaklı and Akbaş.[283]

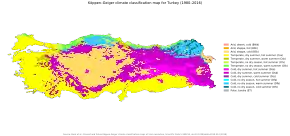

Climate

The coastal areas of Turkey bordering the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas have a temperate Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild to cool, wet winters.[284] The coastal areas bordering the Black Sea have a temperate oceanic climate with warm, wet summers and cool to cold, wet winters.[284] The Turkish Black Sea coast receives the most precipitation and is the only region of Turkey that receives high precipitation throughout the year.[284] The eastern part of the Black Sea coast averages 2,200 millimetres (87 in) annually which is the highest precipitation in the country.[284] The coastal areas bordering the Sea of Marmara, which connects the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea, have a transitional climate between a temperate Mediterranean climate and a temperate oceanic climate with warm to hot, moderately dry summers and cool to cold, wet winters.[284] Snow falls on the coastal areas of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea almost every winter, but usually melts in no more than a few days.[284] However, snow is rare in the coastal areas of the Aegean Sea and very rare in the coastal areas of the Mediterranean Sea.[284] Winters on the Anatolian plateau are especially severe. Temperatures of −30 °C to −40 °C (−22 °F to −40 °F) do occur in northeastern Anatolia, and snow may lie on the ground for at least 120 days of the year, and during the entire year on the summits of the highest mountains. In central Anatolia the temperatures can drop below −20 °C ( -4 °F) with the mountains being even colder.

Mountains close to the coast prevent Mediterranean influences from extending inland, giving the central Anatolian plateau of the interior of Turkey a continental climate with sharply contrasting seasons.[284]

Economy

Turkey is a newly industrialized country, with an upper-middle income economy, which is the twentieth-largest in the world by nominal GDP, and the eleventh-largest by PPP. Turkey is one of the Emerging 7 countries. According to World Bank estimates, Turkey's GDP per capita by PPP is $38,759 in 2022[9] and approximately 11.7% of Turks are at risk of poverty or social exclusion as of 2019.[285] Unemployment in Turkey was 13.6% in 2019,[286] and the middle class population in Turkey rose from 18% to 41% of the population between 1993 and 2010 according to the World Bank.[287] As of September 2021, the foreign currency reserves of the Turkish Central Bank were $74.9 billion (an 8.1% increase compared to the previous month), its gold reserves were $38.5 billion (a 5.1% decrease compared to the previous month), while its official reserve assets stood at $121.3 billion.[288] As of October 2021, the foreign currency deposits of the citizens and residents in Turkish banks stood at $234 billion, equivalent to around half of all deposits.[289][290] The EU–Turkey Customs Union in 1995 led to an extensive liberalisation of tariff rates, and forms one of the most important pillars of Turkey's foreign trade policy.[291]

The automotive industry in Turkey is sizeable, and produced over 1.3 million motor vehicles in 2021, ranking as the 13th largest producer in the world.[292] Turkish automotive companies like TEMSA, Otokar and BMC are among the world's largest van, bus and truck manufacturers. Turkish shipyards are highly regarded both for the production of chemical and oil tankers up to 10,000 dwt and also for their mega yachts.[293] Turkish brands like Beko and Vestel are among the largest producers of consumer electronics and home appliances in Europe, and invest a substantial amount of funds for research and development in new technologies related to these fields.[294][295][296]

.svg.png.webp)

Other key sectors of the Turkish economy are banking, construction, home appliances, electronics, textiles, oil refining, petrochemical products, food, mining, iron and steel, and machine industry. In 2004, it was estimated that 46 percent of total disposable income was received by the top 20 percent of income earners, while the lowest 20 percent received only 6 percent.[297]

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Turkey reached 22.05 billion USD in 2007 and 19.26 billion USD in 2015, but has declined in recent years.[298] In the economic crisis of 2016 it emerged that the huge debts incurred for investment during the AKP government since 2002 had mostly been consumed in construction, rather than invested in sustainable economic growth.[299] In 2020, according to Carbon Tracker, money was being wasted constructing more coal-fired power stations in Turkey.[300] International Energy Agency said that fossil fuel subsidies should be redirected, for example to the health system.[301] Fossil fuel subsidies were around 0.2% of GDP for the first two decades of the 21st century,[302][303] and are higher than clean energy subsidies.[304] The external costs of fossil fuel consumption in 2018 has been estimated as 1.5% of GDP.[305] In 2020 the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development offered to support a just transition away from coal.[306]

Turkey has seen a growth in video gaming industry during the recent years. Many game developing companies founded and gained investment from venture capitalists.[307] TaleWorlds Entertainment, Peak Games, Bigger Games and Dream Games are the current leaders in this sector.[308][309]

Tourism

%252C_Mu%C4%9Fla_Province%252C_southwest_Turkey%252C_Mediterranean.jpg.webp)

Tourism in Turkey has increased almost every year in the 21st century,[310] and is an important part of the economy. The Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism currently promotes Turkish tourism under the project Turkey Home. Turkey is one of the world's top ten destination countries, with the highest percentage of foreign visitors arriving from Europe; specially Germany and Russia in recent years.[310] In 2019, Turkey ranked sixth in the world in terms of the number of international tourist arrivals behind Italy, with 51.2 million foreign tourists visiting the country.[311] Turkey has 19 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and 84 World Heritage Sites in tentative list. Turkey is home to 519 Blue Flag beaches, which makes it in the third place in the world.[312] Istanbul is the tenth most visited city in the world with 13,433,000 annual visitors as of 2018.[313] Antalya is the second most visited city in Turkey, with over 9 million tourists in 2021.[314]

Infrastructure

In 2013 there were 98 airports in Turkey,[316] including 22 international airports.[317] İstanbul Airport is planned to be the largest airport in the world, with a capacity to serve 150 million passengers a year.[318][319] As well as Turkish Airlines, flag carrier of Turkey since 1933, several other airlines operate in the country. It operates scheduled services to 315 destinations in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas, making it the largest mainline carrier in the world by number of passenger destinations.[320][321][322] Turkish Airlines uses Istanbul Airport of 90 million capacity as its main hub.

As of 2014, the country has a roadway network of over 65,000 kilometres (40,400 miles).[323] Motorways are controlled-access highways that are officially named Otoyol. The network spans 3,523 kilometres (2,189 mi) as of 2020. The network is expected to expand to 4,773 kilometres (2,966 mi) by 2023 and to 9,312 kilometres (5,786 mi) by 2035.[324]

Turkish State Railways operates both conventional and high speed trains on 12,532 kilometres rail length. The government-owned national railway company started building high-speed rail lines in 2003. The Ankara-Konya line became operational in 2011, while the Ankara-Istanbul line entered service in 2014.[325] Konya-Karaman line started its operations in 2022 and 406 km (252 mi) long Ankara-Sivas line is to open in 2022.

Opened in 2013, the Marmaray tunnel under the Bosphorus connects the railway and metro lines of Istanbul's European and Asian sides; while the nearby Eurasia Tunnel (2016) provides an undersea road connection for motor vehicles.[326]

Istanbul Metro is the largest metro network in the country with 495 million annual ridership.[327] There are 9 metro lines under service and 6 more under construction.[328]

The Bosphorus Bridge (1973), Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988) and Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge (2016) are the three suspension bridges connecting the European and Asian shores of the Bosphorus strait. The Osman Gazi Bridge (2016) connects the northern and southern shores of the Gulf of İzmit. The Çanakkale 1915 Bridge on the Dardanelles strait, connecting Europe and Asia, is the longest suspension bridge in the world.[330]

Many natural gas pipelines span the country's territory.[159] The Blue Stream, a major trans-Black Sea gas pipeline, delivers natural gas from Russia to Turkey. The undersea pipeline, Turkish Stream, with an annual capacity around 63 billion cubic metres (2,200 billion cubic feet), allows Turkey to resell Russian gas to the rest of Europe.[331] The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, the second longest oil pipeline in the world, was inaugurated in 2005.[332] As of 2018 Turkey consumes 1700 terawatt hours (TW/h) of primary energy per year, a little over 20 megawatt hours (MW/h) per person, mostly from imported fossil fuels.[333] Although the energy policy of Turkey includes reducing fossil-fuel imports, coal in Turkey is the largest single reason why greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey amount to 1% of the global total. Renewable energy in Turkey is being increased and Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant is being built on the Mediterranean coast: but despite national electricity generation overcapacity fossil fuels are still subsidized.[334] Turkey has the fifth-highest direct utilisation and capacity of geothermal power in the world.[335]

As of 2019, Turkey produces 45.6% of its electricity from renewable sources.[336]

Science and technology

TÜBİTAK is the leading agency for developing science, technology and innovation policies in Turkey.[337] TÜBA is an autonomous scholarly society acting to promote scientific activities in Turkey.[338] TAEK is the country's official nuclear energy institution, focused on academic research and the development and implementation of peaceful nuclear technology.[339] It is supervising the construction of Turkey's first nuclear facility, Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant in Mersin, at the cost of $20 billion; the plant is expected to be operational in May 2023,[340] and is projected to meet around 10% of the country's electricity demand.

.JPG.webp)

The Turkish government invests heavily in research and development of military technologies, including Turkish Aerospace Industries, ASELSAN, HAVELSAN, ROKETSAN, and MKE. Turkey is a global leader in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV); the Bayraktar TB2, manufactured by private defence company Baykar, has been exported to over a dozen countries and played a decisive role in several conflicts, including the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[341][342]

Turkey has made significant inroads in aerospace technology into the 21st century. In 2013, it initiated the Turkish Space Launch System (UFS) to develop an independent satellite launch capability, including the construction of a spaceport, the development of satellite launch vehicles, and the establishment of remote earth stations.[343][344][345] Türksat, the country's sole communications satellite operator, has launched a series of satellites into orbit; likewise, the Turkish Satellite Assembly, Integration and Test Center (UMET)—a spacecraft production and testing facility owned by the Ministry of National Defence and operated by the TAI—has launched the Göktürk series of Earth observation satellites for reconnaissance; BILSAT-1 and RASAT are the scientific Earth observation satellites operated by the TÜBİTAK Space Technologies Research Institute.

In 2015, Aziz Sancar, a Turkish professor at the University of North Carolina, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on how cells repair damaged DNA;[346] he is one of two Turkish Nobel laureates, and the first in the sciences. Other prominent Turkish scientists include physician Hulusi Behçet, who discovered Behçet's disease; mathematician Cahit Arf, who defined the Arf invariant; and immunologists Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, whose German biotechnology company, BioNTech, developed one of the first efficacious vaccines against COVID-19.

Turkey is among the top fifty most innovative countries in the world, ranking 41st in the Global Innovation Index in 2021; this represents a considerable increase since 2011, where it was ranked 65th.[347]

Demographics

According to the Address-Based Population Recording System of Turkey, the country's population was 74.7 million people in 2011,[350] nearly three-quarters of whom lived in towns and cities. According to the 2011 estimate, the population is increasing by 1.35 percent each year. Turkey has an average population density of 97 people per km². People within the 15–64 age group constitute 67.4 percent of the total population; the 0–14 age group corresponds to 25.3 percent; while senior citizens aged 65 years or older make up 7.3 percent.[351]

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as "anyone who is bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship"; therefore, the legal use of the term "Turkish" as a citizen of Turkey is different from the ethnic definition.[352] However approximately 70 to 80 percent of the country's citizens are ethnic Turks.[353][4] It is estimated that there are at least 47 ethnic groups represented in Turkey.[354] Reliable data on the ethnic mix of the population is not available, because Turkish census figures do not include statistics on ethnicity.[355]

Kurds are the largest non-Turkish ethnicity at anywhere from 12–25 per cent of the population.[356][357] The exact figure remains a subject of dispute; according to Servet Mutlu, "more often than not, these estimates reflect pro-Kurdish or pro-Turkish sympathies and attitudes rather than scientific facts or erudition".[354] Mutlu's 1990 study estimated Kurds made up around 12 per cent of the population.[358] The Kurds make up a majority in the provinces of Ağrı, Batman, Bingöl, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Hakkari, Iğdır, Mardin, Muş, Siirt, Şırnak, Tunceli and Van; a near majority in Şanlıurfa Province (47%); and a large minority in Kars Province (20%).[359] In addition, due to internal migration, Kurdish diaspora communities exist in all of the major cities in central and western Turkey. In Istanbul, there are an estimated three million Kurds, making it the city with the largest Kurdish population in the world.[360] Non-Kurdish minorities are believed to make up an estimated 7–12 percent of the population.[4]

The three "Non-Muslim" minority groups recognised in the Treaty of Lausanne were Armenians, Greeks and Jews. Other ethnic groups include Albanians, Arabs, Assyrians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Georgians, Laz, Pomaks, and Roma.[4][361][362][363][364] Turkey is also home to a Muslim community of Megleno-Romanians.[365]

Before the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the estimated number of Arabs in Turkey varied from 1 million to more than 2 million.[366] As of April 2020, there are 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, who are mostly Arabs but also include Syrian Kurds, Syrian Turkmen, and other ethnic groups of Syria. The vast majority of these are living in Turkey with temporary residence permits. The Turkish government has granted Turkish citizenship to refugees who have joined the Syrian National Army.[367][368][369]

Largest cities or towns in Turkey TÜİK's address-based calculation from December 2017. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Istanbul  Ankara |

1 | Istanbul | Istanbul | 14,744,519 | 11 | Mersin | Mersin | 1,005,455 |  İzmir  Bursa |

| 2 | Ankara | Ankara | 4,871,884 | 12 | Urfa | Şanlıurfa | 921,978 | ||

| 3 | İzmir | İzmir | 2,938,546 | 13 | Eskişehir | Eskişehir | 752,630 | ||

| 4 | Bursa | Bursa | 2,074,799 | 14 | Denizli | Denizli | 638,989 | ||

| 5 | Adana | Adana | 1,753,337 | 15 | Kahramanmaraş | Kahramanmaraş | 632,487 | ||

| 6 | Gaziantep | Gaziantep | 1,663,273 | 16 | Samsun | Samsun | 625,410 | ||

| 7 | Antalya | Antalya | 1,311,471 | 17 | Malatya | Malatya | 618,831 | ||

| 8 | Konya | Konya | 1,130,222 | 18 | İzmit | Kocaeli | 570,077 | ||

| 9 | Kayseri | Kayseri | 1,123,611 | 19 | Adapazarı | Sakarya | 492,027 | ||

| 10 | Diyarbakır | Diyarbakır | 1,047,286 | 20 | Erzurum | Erzurum | 422,389 | ||

Immigration