Communicable Disease: Parasitic Infections

Congolese Refugee Health Profile

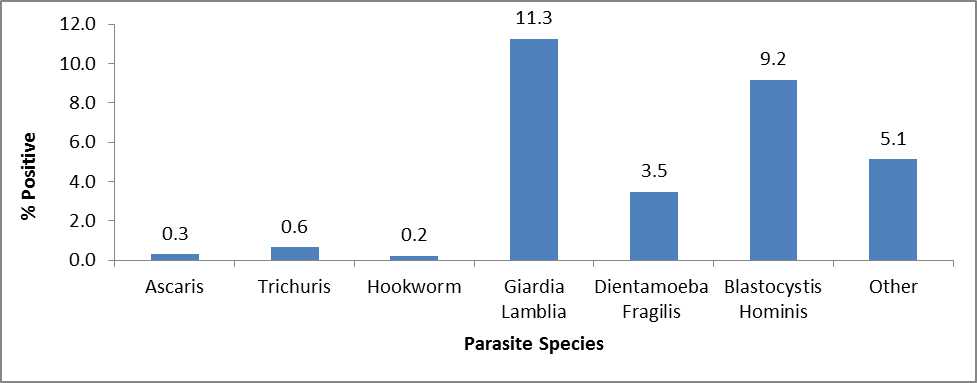

Domestic medical screening data from 4 states have shown a number of parasitic infections that can be diagnosed in Congolese refugees (Figure 9). The following section describes some of the most common parasitic infections among Congolese refugees.

Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic nematode infection that is common in Congolese refugees and is known to persist for more than 50 years in the human host. Infection is frequently asymptomatic but may lead to morbidity and, when the infected individual is immunosuppressed, even result in death. Unlike most parasites that are unable to replicate in the human host, Strongyloides is able to replicate, causing infection that may persist for decades. If strongyloidiasis is not detected promptly after an infected refugee’s arrival, data indicate that the average time to diagnosis in the United States is more than 5 years after migration 18. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome may occur many years after an infected refugee migrates to a non-endemic setting, with case reports occurring >50 years after a refugee’s last known exposure 19, 20, 21. Hyperinfection syndrome, triggered when large numbers of parasites infiltrate internal organs, results in fatality rates exceeding 50%. The syndrome is generally induced when an individual is placed on corticosteroids, although other immunosuppressive conditions (such as cancer and transplant chemotherapeutic immunosuppression) may also trigger it 19, 21. Data from newly arrived Congolese refugees from 1 resettlement state found that 37.5% of 267 specimens tested positive (Figure 12). Testing of specimens for Strongyloides was performed if the refugee was not presumptively treated overseas and if a test was available at the state laboratory. For more information on Strongyloides screening for Congolese refugees, refer to the Health Conditions to Consider in Post-Arrival Medical Screening of Congolese Refugees: Strongyloidiasis section of this profile.

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, caused by S. hematobium and S. mansoni, is common in DRC populations. In addition, infection may be found in all countries of asylum including Burundi, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. Untreated infection generally lasts more than a decade but can persist up to 30 years. Schistosomiasis is associated with liver cirrhosis and resulting clinical complications (S. mansoni, S. japonicum), squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder (S. haematobium), and urinary tract obstruction and renal failure (S. haematobium). Potentially devastating clinical manifestations occasionally occur when the parasite egg enters a refugee’s systemic circulation and travels to a normally sterile site within the body, causing severe inflammation. Eggs may travel to any part of the body, including the brain and spinal cord, where the inflammatory response to the egg may cause paralysis or myelitis. Data obtained from newly arrived Congolese refugees from 2 resettlement states found a 5.6% seroprevalence in 1,279 tested specimens, although not all Congolese refugees were screened for schistosomiasis (Figure 12). Testing of specimens for schistosomiasis was done if the refugee was not presumptively treated overseas. For more information on schistosomiasis presumptive treatment during the Pre-Departure Medical Screening of Congolese refugees refer to the Pre-Departure Medical Screening section of this profile.

Figure 9: Parasites identified by stool ova and parasite examination in Congolese refugees during domestic medical examinations in 4 states from 2010–2013 (n=1,347)

Parasites represented in the Other category include Chilomastix mesnili, Endolimax nana, Entamoeba coli, Entamoeba hartmanni, and Iodamoeba buetshlii

References

- Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Hendel-Paterson BR, Rocha J, Chee-Seong Seet R, Andrea P. Summer AP, et al. Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physician–in-training survey. Am J Med. 2007;120(60):545;e1-8.

- Lim S, Katz K, Krajden S, et al. Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management. CMAJ 2004:171:479-84.

- Gill GV, Beeching NJ, Khoo S, et al. A British Second World War veteran with disseminated strongyloidiasis. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 2004: 98:382-6.

- 21. Newberry AM, Williams DN, Stauffer WM, et al. Strongyloides hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and gram-negative sepsis. Chest 2005;128(5):3681-4.

- Page last reviewed: August 29, 2014

- Page last updated: August 29, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir