Non-Communicable Disease

Chronic, noninfectious health conditions account for a considerable disease burden among all screened Iraqi refugees (3) 28-30. One study showed that 27% (5,095) of Iraqi refugees screened by IOM in Jordan had at least one chronic condition, including hypertension, elevated cholesterol, elevated blood glucose (or diabetes), ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or were overweight or obese 28. Among adult Iraqi refugees screened in California, the most commonly diagnosed chronic conditions were obesity (25%) and hypertension (15%) 26. Other chronic conditions included vision problems; ear, nose, and throat problems (5%); hearing problems (2%); and asthma (2%), arthritis, dental caries, asthma, goiter, hernia, skin allergies, and epilepsy 26.

Cancer

Breast cancer was the most common cause of cancer morbidity among Iraqi refugee women screened outside of Iraq. From 1985-2001 breast cancer was the leading cause of death among Arab-American women in Michigan 31. Although many Arab-American women indicated that their health insurance covered cancer screening, they either had low screening rates or delayed screening 32 33. Availability of health insurance coverage may not be the only barrier to timely cancer screening. Other barriers may include transportation, language, and beliefs about cancer causation and prevention 32 33. Health care providers should be aware of the health perspectives of newly resettled Iraqi refugees and should provide cancer education materials in Arabic to encourage timely screening.

Hypertension

Blood pressure is measured during the visa medical exam and during domestic medical examinations in the United States. Although two or three measurements are required to diagnose an individual with hypertension, single measurements may be used to estimate prevalence of hypertension in a population. In Jordan, of 13,299 US-bound screened Iraqis ≥15 years of age, 33% (4,382) had hypertension. An additional 42% (5,565) of Iraqi refugees were pre-hypertensive 28. Of Iraqi refugees ≥15 years of age arriving to the US from 2008- 2013, 10% self-reported having a history of hypertension.

Diabetes Mellitus

Of the 18,990 Iraqi refugees screened in Jordan in IOM clinics from 2007 through 2009, 514 (3%) were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. Of these, 11% (58) had type I and 89% (456) had type II diabetes. Of those who were diagnosed with diabetes, 84% (343) had hypertension, 22% (113) had pre-hypertension, and 2% (8) had hypertension and a history of angina or myocardial infarction 28.

Obesity

Obesity is a major health issue impacting this population. Of the 11,898 Iraqi refugees ≥ 20 years of age with available weight and height information screened in IOM clinics in Jordan, 38% (4,495) were overweight (BMI = 25.5-29.9 kg/m2), and 34% (3,982) were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Of those who were overweight, 35% (1,581) also had hypertension and of those who were obese, 50% (2,006) had hypertension. Of 5,734 Iraqi refugees 2-19 years of age with available weight and height information, 10% (572) were underweight (<5% of BMI for age), 14% (820) were overweight (85%-95% of BMI for age), and 11% (632) were obese 28.

Smoking

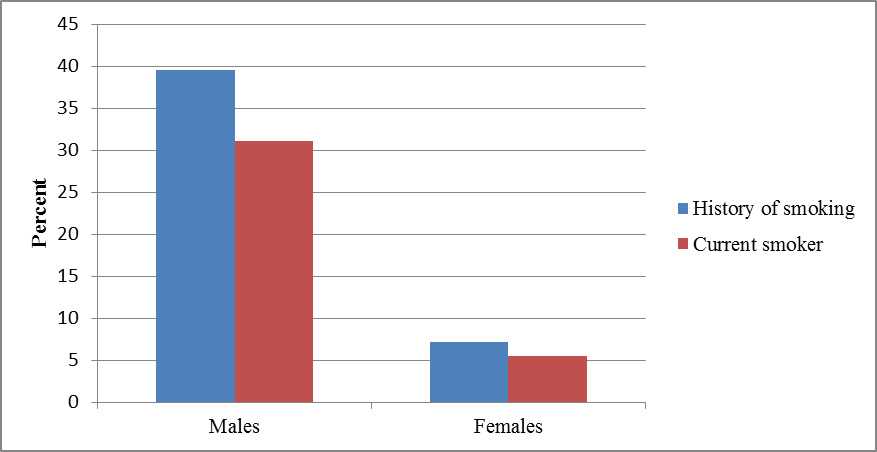

Smoking is widely accepted among Iraqis, particularly Iraqi men (Figure 6). Of Iraqi male refugees ≥15 years old who arrived in the US from 2008 – 2013, 40% had a history of smoking and 31% were current smokers. Smoking among Iraqi women was less common than among Iraqi men.

Figure 6: Self-reported tobacco use among Iraqi refugees during visa medical examinations at panel physician sites, 2008-2013 (N=63,322)

Source: CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification system (EDN) (18)

Congenital and Genetic Disorders

Congenital and genetic disorders are a concern among the Iraqi population. Of the 18,990 screened refugees, 1.7% (325) had congenital disorders: .1% (16) had congenital cardiovascular defects, 0.2% (33) had glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, 0.02% (4) had sickle cell disease, 7 (0.03%) thalassemia, and 116 (0.6%) congenital hemangioma. The Iraq Family Health Survey reported that 37% of Iraqi women are married to their cousins and 23% to other relatives, which may partially account for the high prevalence of certain recessively inherited disorders 9 28. Health care providers serving Iraqi families should inquire about consanguinity and become familiar with the genetic disorders common among Arabs, such as G6PD deficiency, sickle cell disease, and thalassemia 28.

Lead Poisoning

Iraqi refugee children specifically do not appear to be at higher risk of lead poisoning than US children. Only 1.3% of Iraqi children ≤5 years of age screened in San Diego during 2008–2009 had elevated blood lead levels (≥10 µg/dL) 26. However, refugee children in general are thought to be at higher risk for lead poisoning, not only because anemia and malnutrition increase lead absorption, but also because of an increased risk for exposure to products containing lead.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Iraq Fact Sheet. 2010. Accessed November 2013. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486426.html

- Queensland Health Multicultural Services. Community Profiles for Healthcare Providers: Iraqi Australians. Queensland Health. [Online] July 8, 2011. [Cited: September 13, 2011.] www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural.

- Giese, Amanda. An Assessment of the Health of Iraqi Refugees in Chicago. Heartland Alliance. 2010.

- Harper, Andrew. Iraq's Refugees: Ignored and Unwanted. 869, 2008, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 90, pp. 169-190.

- Doocy, Shannon, et al. Food Security and Humanitarian Assistance Among Displaced Iraqi Populations in Jordan and Syria. 2, 2011, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 72, pp. 273-282.

- Ghareeb, Edmund, Ranard, Donald and Tutunji, Jenab. Refugees from Iraq: Their History, Cultures, and Background Experiences. Center for Applied Linguistics. 2008. COR Center Enhanced Refugee Backgrounder No. 1.

- Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Iraqi Refugee Women and Youth in Jordan: Reproductive Health Findings, A Snapshot from the Field. 2007.

- Taylor, Eboni et al. Physical and Mental Health Status of Iraqi Refugees Resettled in the United States. Springer, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, August, 2013. Web. August, 2013.

- Iraq Family Health Survey 2006/7 (World Health Organization). Accessed 2012, at http://www.emro.who.int/iraq/pdf/ifhs_report_en.pdf).rm

- Terrazas, Aaron. Iraqi Immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. [Online] March 5, 2009. [Cited: September 9, 2011.] http://www.migrationinformation.org/USfocus/display.cfm?id=721.

- O'Donnell, Kelly and Newland, Kathleen. The Iraqi Refugee Crisis: The Need for Action. Migration Policy Institute. 2008.

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Tips for Health Care Providers about Iraqi Refugees. 2010.

- Stratis Health. Iraqis in Minnesota. Stratis Health. [Online] 11 1, 2009. [Cited: September 13, 2011.] http://www.stratishealth.org.

- Saadi, Altaf, Bond, Barbara and Percac-Lima, Sanja. Perspectives on Preventive Health Care and Barriers to Breast Cancer Screening Among Iraqi Women Refugees. 2011, Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. PMID 21901446 .

- IRC Commission on Iraqi Refugees. A Tough Road Home: Uprooted Iraqis in Jordan, Syria and Iraq. New York : International Rescue Committee, 2010.

- Frelick, Bill. "The Silent Treatment": Fleeing Iraq, Surviving in Jordan. [ed.] Peter Bouckhaert, Christoph Wilcke and Sarah Leah Whitson. Human Rights Watch. November 2006, Vol. 18, 10.

- Schinina, et al. Assessment on Psychosocial Needs of Iraqis Displaced in Jordan and Lebanon. International Organization for Migration. 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012), Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN).

- US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS).

- Joint Appeal by UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. Meeting the Health Needs of Iraqis Displaced in Neighbouring Countries. 2007.

- World Health Organization/UNICEF/Johns Hopkins University. The Health Status of the Iraqi Population in Jordan: 2009

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; United Nations Children's Development Fund; World Food Program. Assessment on the Situation of Iraqi Refugees in Syria. 2006.

- Women's Refugee Commission. Baseline Study: Dcumenting Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Iraqi Refugees and the Status of Family Planning Services in UNHCR's Operations in Amman, Jordan. 2011.

- Chynoweth, Sarah. The Need for Priority Reproductive Health Services for Displaced Iraqi Women and Girls. 31, 2008, Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 16, pp. 93-102.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO) website. Accessed September, 2012. http://www.emro.who.int/

- Ramos, M, et al. Health of Resettled Iraqi Refugees–San Diego County, California, October 2007-September 2009. 2010, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 59, pp. 1614-1618.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Profile: Iraq. World Health Organization. [Online] January, 29th 2013. [Cited: January 29th, 2013] www.who.int/tb/data.

- Yanni, E, et al; The Health Profile and Chronic Diseases Comorbidities of US-Bound Iraqi Refugees Screened by the International Organization for Migration in Jordan: 2007–2009. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health; DOI 10.1007/s10903-012-9578-6

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Disease Profile: Iraq. World Health Organization. [Online] September 12, 2011. [Cited: September 12, 2011.] http://Infobase.who.int.

- International Rescue Committee. The Health of Refugees from Iraq. 2009. http://www.rescue.org/iraqi-refugees.

- Darwish-Yassine M, Wing D. Cancer epidemiology in Arab Americans and Arabs outside the Middle East. Ethn Dis. 2005;15 (1 Suppl 1):S1-5–S1-8.

- 32. Michigan Department of Community Health. Color me healthy: a profile of Michigan’s racial/ethnic populations, May 2008. 2011. Accessed on 22 Jan 2011 at http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/ColorMeHealthyProfileMay2008_2362457.pdf

- Shah SM, et al. Arab American Immigrants in New York: health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:429–36.

- Alhasnawi, Salih, et al. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS). 2, 2009, World Psychiatry, Vol. 8, pp. 97-109.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2013 UNHCR country operations profile – Iraq. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486426.html

- Page last reviewed: December 19, 2014

- Page last updated: December 19, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir