1510 influenza pandemic

| 1510 flu pandemic | |

|---|---|

The 1510 flu pandemic was the first to be chronicled across continents. | |

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | unknown |

| Location | Asia, Africa, and Europe |

| Date | Early Summer to Fall of 1510 |

Deaths | unknown, death rate ~1% [1] |

In 1510, an acute respiratory disease emerged in Asia[2][1][3] before spreading through North Africa and Europe during the first chronicled, inter-regional flu pandemic generally recognized by medical historians and epidemiologists.[4][1][5][6][7][8][9] Influenza-like illnesses had been documented in Europe since at least Charlemagne,[1] with 1357's outbreak the first to be called influenza,[10][8] but the 1510 flu pandemic is the first to be pathologically described[11][12] following communication advances brought about by the printing press. Flu became more widely referred to as coqueluche and coccolucio in France and Sicily during this pandemic,[13][14] variations of which became the most popular names for flu in early modern Europe.[1] The pandemic caused significant disruption in government, church, and society[15][3][6] with near-universal infection[16] and a mortality rate of around 1%.[1]

Asia

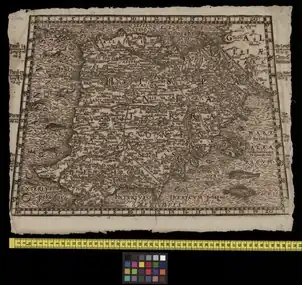

The 1510 flu is suspected of originating in East Asia,[1] possibly China.[2] Gregor Horst writes in Operum medicorum tombus primus (1661) that the disease came from Asia and spread along trade routes[1] before attacking the Middle East and North Africa. German medical writer Justus Hecker suggested the 1510 influenza most likely came from Asia because of the historical nature of other influenzas to originate there in more recent pandemics.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Middle East

The flu spread along trade routes towards North Africa,[1] traveling southwest through the Middle East. Frequently visited cities like Jerusalem and Mecca would have almost certainly been reached by the flu, with large volumes of people destined to travel to Egypt, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire.

Africa

It is generally understood that the 1510 influenza had spread in Africa before Europe.[17][9] Influenza was likely widespread in North Africa before crossing continents through the Mediterranean, arriving in Malta[4][18] where British medical historian Thomas Short believed that the "island of Melite in Africa" became the 1510 flu's springboard into Europe.[17][19]

Europe

Europe's internationally traveled cities and flu's highly contagious nature enabled its spread through European populations. The 1510 flu disrupted royal courts, church services, and social life across Europe. Contemporary chroniclers and those who've read their accounts observed how entire populations were attacked at once,[17][1] which is how the disease first received the name influenza (from the belief that such outbreaks were caused by influences like stars or cold).[10] Turin professor Francisco Vallerioli (aka Valleriola) writes that the 1510 flu featured "Constriction of breathing, and beginning with a hoarseness of voice and... shivering. Not long after that there being a cooked humor which fills the lungs."[1] Physicians like Valleriola described the 1510 flu as more fatal to children[20] and those who were bled.[17] Lawyer Francesco Muralto noted that "the disease killed 10 people out of a thousand in one day," supporting a fatality rate of around 1%.[1]

Sicily and the Italian Kingdoms

The first cases of influenza began to appear in Sicily around July[21] after the arrival of infected merchant ships from Malta.[17][2][22] In Sicily it was commonly called coccolucio for the hood (resembling a coqueluchon - a kind of monk's cowl) the sick often wore over their heads.[23][24][17] Influenza quickly spread out along the Mediterranean coasts of Italy and southern France[21] via merchant ships leaving the island.

In Emilia-Romagna, Tommasino de' Bianchi recorded the recovery of Modena's first cases on 13 July 1510, writing that in the city "there appears an illness that lasts three days with a great fever, and headache and then they rise... but there remains a terrible cough that lasts maybe eight days, and then they recover."[1] This data would indicate that the first cases of flu, which has an incubation period of one to four days, began to fall ill in the Emilia-Romagna region around late June or early July. Pope Julius II attributed the outbreaks in Rome and the Holy See to God's wrath.[1]

Central Europe

Flu spread over the Alps into Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire. In Switzerland it is documented as being called das Gruppie by the Mellingen chronicler Anton Tegenfeld,[25] the flu nickname then preferred by German-speaking Europeans. A respiratory illness seemed to have menaced the Canton of Aargua in June, with the population falling ill with sniffling, coughing, and fatigue.[26] German physician Achilles Gasser recorded a deadly epidemic spreading over the Holy Roman Empire's upper kingdoms, branching into the cities and the "whole mankind:" Mira qua edam Epidemia mortales per urbes hanc totamque adeo superiorem Germaniam corripiebat, qua aegri IV vel V ad summum dies molestissimis destillationibus laborabant ac ration privati instar phrenicorum furebant, atque inde iterum convalescebant, paucissimis ad Gorcum demissis.[16]

André de Burgo's letters dated 24 August 1510 indicate Margaret of Austria had to intervene at a royal assembly between her father, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and Louis XII of France because the King of France was too sick with "coqueluche" to be spoken to.[27] Influenza spread out from the Holy Roman Empire towards Northern Europe, the Baltic states,[14] and west towards France and England.[17]

France

Arriving aboard infected sailors from Sicily, influenza struck the Kingdom of France through the ports of Marseille and Nice and spread through the international crowds of the shipyards. Merchants, pilgrims, and other travelers from the south and east spread the virus throughout the western Mediterranean in July.[26] It was referred to as "cephalie catarrhal" among French physicians, but more commonly just called coqueluche.[1][13][27][7][28][29] Historian François Eudes de Mézeray traced the etymology of "coqueluche" to an outbreak 1410s[30] during which sufferers wore hoods resembling coqueluchons, a kind of monk's cowl.[31] French surgeon Ambroise Paré described the outbreak as having been a "rheumatic affliction of the head...with constriction of the heart and lungs."[1] By August it had appeared in Tours and after it had propagated itself throughout France over summer, sickening the entire country by September.[30] French poet and historian Jean Bouchet, employed by King Louis XII's Royal Court, wrote that the epidemic "appeared in the entire Kingdom of France, as much in the towns as in the countryside."[1]

Coqueluche filled up the hospitals in France.[32] King Louis XII's National Assembly of Bishops, Prelates, and university professors scheduled for September 1510 was delayed because of the intensity of the flu in Paris.[6] Jean Fernel (aka Fernelius), physician to Henry III of France, compares the 1557 influenza to the 1510 epidemic which attacked everyone with fever, a heaviness in their head, and profound coughing.[4] Up to 1000 Parisians per day were dying at the height of the "1510 peste."[33] Mézeray mentions that it disrupted judicial proceedings and colleges,[15][3] and that the 1510 flu was more widespread and deadly in France than in other countries.[34]

Cardinal Georges d'Amboise, a close friend and advisor to the King of France, is sometimes believed to have died of influenza since his health sharply declined after arriving in Lyons in May 1510.[35] The cardinal, also known as Monseigneur le Ledat, made his final testimony and recited Sacraments around 22 May[36] before he died on the 25th. His sudden decline in health and flu's arrival in Europe around early summer have created uncertainty as to whether he died of gout or influenza, but "coqueluche" is not mentioned in French royal correspondence that year until August.[27]

England and Ireland

British medical historian Charles Creighton claimed there is one foreign account of the 1510 flu in England,[14] but did not elaborate.[14] Fernel and Paré suggested that the 1510 influenza "spread to almost all countries of the world" (not concerning Spain's territories in the New World).[1] An epidemiological study of past influenza pandemics reviewing previous medical historians' data has found England was affected in 1510[37] and there were reports of symptoms like "gastrodynia" and noteworthy murrain among cattle.[38] The 1510 flu is also recorded to have reached Ireland.[39]

Spain and Portugal

Influenza reached the Iberian Peninsula early after Italy, due to the highly interconnected trade and pilgrimage routes between Spain, Portugal, and the Italian kingdoms. Cases began to appear in Portugal around the same time the disease entered the Holy Roman Empire.[17] Spanish cities were reportedly "dispopulated" by the 1510 flu.[9]

The Americas

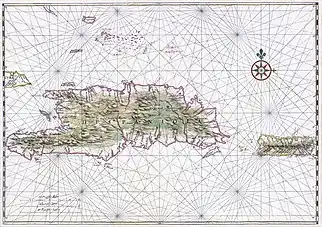

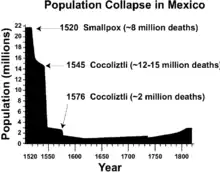

There are no records of influenza affecting the New World in 1510,[40]even though Spain was sending fleets of ships across the Atlantic. The first recorded flu outbreak in the New World had afflicted the Isle of Santo Domingo (Now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1493.[41]Amerindian populations sharp decline due to Spanish-imported diseases in these 1490s and early 1500s is however documented, most notably due to smallpox.

Medicine and Treatment

Blistering on the back of the head and shoulders was one form of treatment prescribed in Europe for the flu.[1] Paré regarded the common treatments of bloodletting and purgation to be especially dangerous to 1510's flu patients.[1] Supraorbital pain and vision problems were symptoms[22] of coqueluche, so sufferers may have felt tempted to wear hoods due to light sensitivity. Short describes some medicinal treatments for the 1510 flu including "Bole Armoniac, oily lintus, pectoral troches, and decoctions."[17]

Origin of 1510 Influenza

Justus Hecker and John Parkin presumed the 1510 influenza originated from East Asia because of the historical nature of other influenza pandemics to originate there,[3][42] while in 1661 Gregor Horst wrote that the 1510 flu spread along trade routes from East Asia to Africa before reaching Europe.[1] Influenza viruses sometimes leap from Asia's migratory water fowl after massive migrations congregate near water sources for humans and domesticated animals, in which cross-species infections trigger antigenic shift and create new strains of flu human beings have little immunity to.[43] European chroniclers noticed that the 1510 influenza did appear in North Africa before Europe, which has led some medical historians to suggest it may have developed there[39](parts of North Africa also lie along migratory bird ways, specifically the east Africa-West Asia and Black Sea-Mediterranean routes, that make it vulnerable to spontaneous reassortment of pandemic flu viruses).[44] There remains no chronicled or biological evidence to suggest the 1510 flu originated from, as opposed to just spread in, Africa before reaching Europe.

Debunking suggestions of whooping cough

The 1510 "coqueluche" has been recognized as influenza by modern epidemiologists[6][1] and medical historians.[14][45][46] Suggestions that the 1510 coqueluche was whooping cough have been doubted[47] because adult sufferers often experienced "precipitous"[1] symptoms described by contemporaries like Tommasino de Bianchi[1] or Valleriola as high fever for 3 days, headache, prostration, loss of sleep and appetite, delirium,[7] a cough most severe on the 5th to 10th days,[15][48] lung congestion,[1] and slow recovery beginning on the second week.[17][3] Adults with pertussis will usually cough for weeks before becoming gradually more ill then recovering over a period of months.[49][50] The coqueluche of 1510 is considered to be influenza by experts because of its sudden symptoms, explosive spread,[8] and timelines of sickness to recovery. The first outbreak of whooping cough to be agreed on by most medical historians is Guillaume de Baillou's description of an outbreak in Paris in 1578.[47]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Morens, David; North, Michael; Taubenberger, Jeffrey (4 December 2011). "Eyewitness accounts of the 1510 influenza pandemic in Europe". Lancet. 367 (9756): 1894–1895. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62204-0. PMC 3180818. PMID 21155080.

- 1 2 3 Parkin, John (1880). Epidemiology; or, The remote cause of epidemic diseases in the animal and in the vegetable creation. J. and A. Churchill.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hecker, Justus Friedrich Carl; Babington, Benjamin Guy (1859). The epidemics of the middle ages. London: Trübner & co. pp. 202–205.

- 1 2 3 Stedman, Thomas, ed. (1898). Twentieth Century Practice: An International Encyclopedia of Modern Medical Science by Leading Authors of Europe and America. Vol. 15. New York: W. Wood. p. 11.

- ↑ Ghendon, Youri (1994). "Introduction to Pandemic Influenza through History on". European Journal of Epidemiology. 10 (4): 451–453. doi:10.1007/BF01719673. JSTOR 3520976. PMID 7843353. S2CID 2258464.

- 1 2 3 4 Morens, David; Taubengerger, Jeffrey; Folkers, Gregory; Fauci, Anthony (15 December 2010). "Pandemic Influenza's 500th Anniversary". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 51 (12): 1442–1444. doi:10.1086/657429. PMC 3106245. PMID 21067353.

- 1 2 3 FORBES, JOHN (1839). THE BRITISH AND FOREIGN MEDICAL REVIEW OF QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE AND SURGERY. p. 108.

- 1 2 3 Morens, David M.; Taubenberger, Jeffery K. (27 June 2011). "Pandemic influenza: certain uncertainties". Reviews in Medical Virology. 21 (5): 262–284. doi:10.1002/rmv.689. ISSN 1052-9276. PMC 3246071. PMID 21706672.

- 1 2 3 Ryan, Jeffrey R. (2008-08-01). Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Planning and Community Preparedness. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4200-6088-1.

- 1 2 A. Mir, Shakil (December 2009). "History of Swine Flu". JK Science. PG Department of Pharmacology, Govt Medical College, Srinagar. 8: 163 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Riverside, Clifford E. Trafzer, University of California; McCoy, Robert R. (2009-03-20). Forgotten Voices: Death Records of the Yakama, 1888-1964. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8108-6648-5.

- ↑ "Scientists explore 1510 influenza pandemic and lessons learned". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- 1 2 Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales (in French). Asselin. 1877. p. 332.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain ... Cambridge, UK: The University Press. pp. 399–400.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopedia of Practical Medicine: Variolla, Vaccination, Vericella, Cholera, Erysipelas, Whooping Cough, Hay Fever. Saunders. 1902. p. 542.

- 1 2 3 SCHWEICH, Heinrich; HECKER, Justus Friedrich Carl (1836). Die Influenza. Ein historischer und ätiologischer Versuch ... Mit einer Vorrede von ... J. F. C. Hecker (in German). p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Thomson, Theophilus (1852). Annals of Influenza or Epidemic Catarrhal Fever in Great Britain. The Sydenham Society Instituted. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ↑ Stedman, Thomas Lathrop (1898). Twentieth Century Practice: Infectious diseases. New York: W. Wood. p. 11.

- ↑ Short, Thomas (1749). A General Chronological History of the Air, Weather, Seasons, Meteors, &c. in Sundry Places and Different Times: More Particularly for the Space of 250 Years : Together with Some of Their Most Remarkable Effects on Animal (especially Human) Bodies and Vegetables. London: T. Longman ... and A. Millar. p. 203.

- ↑ Vaughan, Warren Taylor (1921). Influenza: An Epidemiologic Study. Baltimore, Maryland: American journal of hygiene. p. 157. ISBN 9780598840387.

- 1 2 Alibrandi, Rosamaria. "When early modern Europe caught the flu. A scientific account of pandemic influenza in sixteenth century Sicily". Medicina Historica. 2: 19–25.

- 1 2 Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales: publié sous la direction de MM. les docteurs Raige-Delorme et A. Dechambre (in French). P. Asselin, S' de Labé, V. Masson et fils. 1882. p. 220.

- ↑ Potter, C. W. (2001). "A history of influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. ISSN 1365-2672. PMID 11576290. S2CID 26392163.

- ↑ Beveridge, W.I.B (1991). "The Chronicle of Influenza Epidemics". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 13 (2): 223–234. PMID 1724803 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Karsten, Gustaf (1920). The Journal of English and German Philology. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. p. 513.

- 1 2 Schindler, Wolfgang; Untermann, Jürgen (1999). Grippe, Kamm und Eulenspiegel: Festschrift für Elmar Seebold zum 65. Geburtstag (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 244. ISBN 978-3-11-015617-1.

- 1 2 3 Louis, X. I. I.; Godefroy (1712). Lettres du roi Louis XII et du cardinal Georges d'Amboise: depuis 1504 à 1514 (in French). Foppens. pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Katona, Mihaly (1833). Abhandlung über die Grippe (Influenza) in Wien in dem Jahre 1833 (in German). Edl. v. Schmid. pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Desruelles, Henry-Marie-Joseph (1827). Traite De La Coqueluche, d'apres les Principes de la Doctrine Physiologique (in French). Paris: J. B. Bailliere. p. 22.

- 1 2 Corradi, Alfonso (1867). Annali delle epidemie occorse in Italia dalle prime memorie fino al 1850 scritti da Alfonso Corradi: Dal 1501 a tutto il 1600 con una tavola delle cose piu memorabili si della 1. che della 2. parte (in Italian). Tipi Gamberini e Parmeggiani. p. 19.

- ↑ Doyen, Guillaume Le (1857). Annalles et chronicques du pais de Laval et parties circonvoisines depuis l'an de Nostre Seigneur Ihesu-Crist 1480 jusqú à l'année 1537, avec un préambule retrospectif du temps anticque jadis (in French). H. Godbert. p. 134.

- ↑ La Revue Mondial. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. 1919. p. 262.

- ↑ Quintessence de l'économie politique transcendante à l'usage des électeurs et des philosophes par le baron de Münster (in French). Dutertre. 1842. p. 72.

- ↑ Bergeron, Georges (1874). Des Caractèrs Généraux des Affections Catarrhals Aigues (in French). A. Delahaye. p. 35.

- ↑ Wright, Thomas (1856). The History of France: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. London: London Print. and Publishing Company. pp. A.D. 1510.

- ↑ Louis, X. I. I.; Godefroy (1712). Lettres du roi Louis XII et du cardinal Georges d'Amboise: depuis 1504 à 1514 (in French). Foppens. p. 233.

- ↑ The American Journal of Hygiene: Monographic series. Johns Hopkins Press. 1921. p. 7.

- ↑ Kilbourne, E. D. (2012-12-06). Influenza. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4684-5239-6.

- 1 2 Bray, R. S. (1996). Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History. Cambridge, England: ISD LLC. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-7188-4816-3.

- ↑ Morens, David; North, Michael; Taubenberger, Jeffrey (4 December 2011). "Eyewitness accounts of the 1510 influenza pandemic in Europe". Lancet. 367 (9756): 1894–1895. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62204-0. PMC 3180818. PMID 21155080.

- ↑ Guerre, M.D., Francisco (Fall 1988). "The Earliest American Epidemic: The Influenza of 1493". Social Science History. 12 (3): 305–325. doi:10.1017/S0145553200018599. PMID 11618144 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Charles Alexander (1884). An Epitome of the Reports of the Medical Officers to the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service, from 1871 to 1882: With Chapters on the History of Medicine in China, Materia Medica, Epidemics, Famine, Ethnology, and Chronology in Relation to Medicine and Public Health. London: Baillière, Tindall, and Cox. p. 348.

- ↑ "The Origin of New Flu Strains". sphweb.bumc.bu.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ↑ Baghi, Hossein Bannazadeh; Soroush, Mohammad Hossein (2018-05-01). "Influenza: the role of the Middle East and north Africa?". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (5): 498. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30213-5. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 29695361.

- ↑ Dunglison, M.D., Robley (1848). The Practice of Medicine: A Treatise on Special Pathology and Therapeutics. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard. p. 278. ISBN 9780608426761.

- ↑ Vaughan, Warren Taylor (1921). Influenza: An Epidemiologic Study. American journal of hygiene. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-598-84038-7.

- 1 2 Whooping Cough: Essential Facts Concerning Whooping Cough, Its Prevention and Treatment with Appropriate Vaccines. Indianapolis, Indiana: Eli Lilly & Company. 1920. p. 3.

- ↑ Stedman, Thomas, ed. (December 21, 1918). "Paris Epidemics of the XVI Century". Medical Record: A Weekly Journal of Medicine and Surgery. M.M. Wood & Co. 94: 1076.

- ↑ "Pertussis". CHEST Foundation. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ↑ American Association for the Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality: Transactions of the Annual Meeting - Milwaukee, October 19-21, 1916. Baltimore: Franklin Printing Company. 1917. p. 126.