Asbestosis

| Asbestosis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A plaque caused by asbestos exposure on the diaphragmatic pleura. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, chest pain[1] |

| Complications | Lung cancer, mesothelioma, pleural fibrosis, pulmonary heart disease[1][2] |

| Usual onset | ~10-40 years after long-term exposure[3] |

| Causes | Asbestos[4] |

| Diagnostic method | History of exposure, medical imaging[4] |

| Prevention | Eliminating exposure[4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, stopping smoking, vaccination, oxygen therapy[5][4] |

| Prognosis | Up to 40% continue to worsen[6] |

| Frequency | 157,000 (2015)[7] |

| Deaths | 3,600 (2015)[8] |

Asbestosis is long term inflammation and scarring of the lungs due to asbestos fibers.[4] Symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness.[1] Complications may include lung cancer, mesothelioma, and pulmonary heart disease.[1][2]

Asbestosis is caused by breathing in asbestos fibers.[1] Generally it requires a relatively large exposure over a long period of time.[1] Such levels of exposure typically only occur in those who work with the material.[2] All types of asbestos fibers are associated with an increased risk.[9] It is generally recommended that currently existing and undamaged asbestos be left undisturbed.[10] Diagnosis is based upon a history of exposure together with medical imaging.[4] Asbestosis is a type of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis.[4]

There is no specific treatment.[1] Recommendations may include influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination, oxygen therapy, and stopping smoking.[5] Asbestosis affected about 157,000 people and resulted in 3,600 deaths in 2015.[8][7] Asbestos use has been banned in a number of countries in an effort to prevent disease.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of asbestosis typically manifest after a significant amount of time has passed following asbestos exposure, often several decades under current conditions in the US.[11] The primary symptom of asbestosis is generally the slow onset of shortness of breath, especially with physical activity.[12] Clinically advanced cases of asbestosis may lead to respiratory failure. When a physician listens with a stethoscope to the lungs of a person with asbestosis, they may hear inspiratory crackles.

The characteristic pulmonary function finding in asbestosis is a restrictive ventilatory defect.[13] This manifests as a reduction in lung volumes, particularly the vital capacity (VC) and total lung capacity (TLC). The TLC may be reduced through alveolar wall thickening; however, this is not always the case.[14] Large airway function, as reflected by FEV1/FVC, is generally well preserved.[11] In severe cases, the drastic reduction in lung function due to the stiffening of the lungs and reduced TLC may induce right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale).[15][16] In addition to a restrictive defect, asbestosis may produce reduction in diffusion capacity and a low amount of oxygen in the blood of the arteries.

Cause

The cause of asbestosis is the inhalation of microscopic asbestos mineral fibers suspended in the air.[17] In the 1930s, E. R. A. Merewether found that greater exposure resulted in greater risk.[18]

Pathogenesis

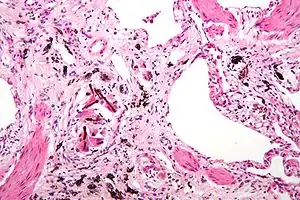

Asbestosis is the scarring of lung tissue (beginning around terminal bronchioles and alveolar ducts and extending into the alveolar walls) resulting from the inhalation of asbestos fibers. There are two types of fibers: amphibole (thin and straight) and serpentine (curly). All forms of asbestos fibers are responsible for human disease as they are able to penetrate deeply into the lungs. When such fibers reach the alveoli (air sacs) in the lung, where oxygen is transferred into the blood, the foreign bodies (asbestos fibers) cause the activation of the lungs' local immune system and provoke an inflammatory reaction dominated by lung macrophages that respond to chemotactic factors activated by the fibers.[19] This inflammatory reaction can be described as chronic rather than acute, with a slow ongoing progression of the immune system attempting to eliminate the foreign fibers. Macrophages phagocytose (ingest) the fibers and stimulate fibroblasts to deposit connective tissue. Due to the asbestos fibers' natural resistance to digestion, some macrophages are killed and others release inflammatory chemical signals, attracting further lung macrophages and fibrolastic cells that synthesize fibrous scar tissue, which eventually becomes diffuse and can progress in heavily exposed individuals. This tissue can be seen microscopically soon after exposure in animal models. Some asbestos fibers become layered by an iron-containing proteinaceous material (ferruginous body) in cases of heavy exposure where about 10% of the fibers become coated. Most inhaled asbestos fibers remain uncoated. About 20% of the inhaled fibers are transported by cytoskeletal components of the alveolar epithelium to the interstitial compartment of the lung where they interact with macrophages and mesenchymal cells. The cytokines, transforming growth factor beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha, appear to play major roles in the development of scarring inasmuch as the process can be blocked in animal models by preventing the expression of the growth factors.[20][21] The result is fibrosis in the interstitial space, thus asbestosis. This fibrotic scarring causes alveolar walls to thicken, which reduces elasticity and gas diffusion, reducing oxygen transfer to the blood as well as the removal of carbon dioxide. This can result in shortness of breath, a common symptom exhibited by individuals with asbestosis.[22]

Diagnosis

According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the general diagnostic criteria for asbestosis are:[11]

- Evidence of structural pathology consistent with asbestosis, as documented by imaging or histology

- Evidence of causation by asbestos as documented by the occupational and environmental history, markers of exposure (usually pleural plaques), recovery of asbestos bodies, or other means

- Exclusion of alternative plausible causes for the findings

The abnormal chest x-ray and its interpretation remain the most important factors in establishing the presence of pulmonary fibrosis.[11] The findings usually appear as small, irregular parenchymal opacities, primarily in the lung bases. Using the ILO Classification system, "s", "t", and/or "u" opacities predominate. CT or high-resolution CT (HRCT) are more sensitive than plain radiography at detecting pulmonary fibrosis (as well as any underlying pleural changes). More than 50% of people affected with asbestosis develop plaques in the parietal pleura, the space between the chest wall and lungs. Once apparent, the radiographic findings in asbestosis may slowly progress or remain static, even in the absence of further asbestos exposure.[23] Rapid progression suggests an alternative diagnosis.

Asbestosis resembles many other diffuse interstitial lung diseases, including other pneumoconiosis. The differential diagnosis includes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and others. The presence of pleural plaques may provide supportive evidence of causation by asbestos. Although lung biopsy is usually not necessary, the presence of asbestos bodies in association with pulmonary fibrosis establishes the diagnosis.[24] Conversely, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of asbestos bodies is most likely not asbestosis.[11] Asbestos bodies in the absence of fibrosis indicate exposure, not disease.

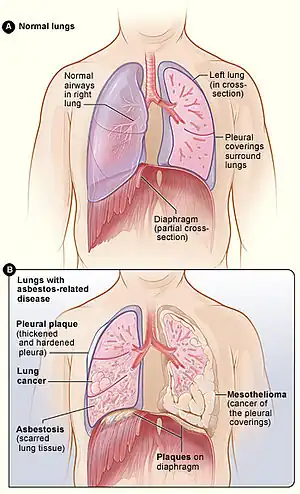

Figure A shows the location of the lungs, airways, pleura, and diaphragm in the body. Figure B shows lungs with asbestos-related diseases, including pleural plaque, lung cancer, asbestosis, plaque on the diaphragm, and mesothelioma.

Figure A shows the location of the lungs, airways, pleura, and diaphragm in the body. Figure B shows lungs with asbestos-related diseases, including pleural plaque, lung cancer, asbestosis, plaque on the diaphragm, and mesothelioma..jpg.webp) Extensive fibrosis of pleura and lung parenchyma.

Extensive fibrosis of pleura and lung parenchyma..jpg.webp) The arrow points to an uncoated segment of asbestos fiber in this ferruginous body.

The arrow points to an uncoated segment of asbestos fiber in this ferruginous body..jpg.webp) Severe pleural fibrosis with focal calcification.

Severe pleural fibrosis with focal calcification..jpg.webp) The black arrows point to ferrugionous bodies that are located at the periphery of a focus of non-small cell lung carcinoma, NOS.

The black arrows point to ferrugionous bodies that are located at the periphery of a focus of non-small cell lung carcinoma, NOS. 61 yr old working industrially with asbestos for decades.

61 yr old working industrially with asbestos for decades.

Treatment

There is no cure available for asbestosis.[25] Oxygen therapy at home is often necessary to relieve the shortness of breath and correct underlying low blood oxygen levels. Supportive treatment of symptoms includes respiratory physiotherapy to remove secretions from the lungs by postural drainage, chest percussion, and vibration. Nebulized medications may be prescribed in order to loosen secretions or treat underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immunization against pneumococcal pneumonia and annual influenza vaccination is administered due to increased sensitivity to the diseases. Those with asbestosis are at increased risk for certain cancers. If the person smokes, quitting the habit reduces further damage. Periodic pulmonary function tests, chest x-rays, and clinical evaluations, including cancer screening/evaluations, are given to detect additional hazards.

Society and culture

Legal issues

The death of English textile worker Nellie Kershaw in 1924 from pulmonary asbestosis was the first case to be described in medical literature, and the first published account of disease attributed to occupational asbestos exposure. However, her former employers (Turner Brothers Asbestos) denied that asbestosis even existed because the medical condition was not officially recognised at the time. As a result, they accepted no liability for her injuries and paid no compensation, either to Kershaw during her final illness or to her family after her death. Even so, the findings of the inquest into her death were highly influential insofar as they led to a parliamentary enquiry by the British Parliament. The enquiry formally acknowledged the existence of asbestosis, recognised that it was hazardous to health and concluded that it was irrefutably linked to the prolonged inhalation of asbestos dust. Having established the existence of asbestosis on a medical and judicial basis, the report resulted in the first Asbestos Industry Regulations being published in 1931, which came into effect on 1 March 1932.[26][27]

The first lawsuits against asbestos manufacturers occurred in 1929. Since then, many lawsuits have been filed against asbestos manufacturers and employers, for neglecting to implement safety measures after the link between asbestos, asbestosis and mesothelioma became known (some reports seem to place this as early as 1898 in modern times). The liability resulting from the sheer number of lawsuits and people affected has reached billions of U.S. dollars. The amounts and method of allocating compensation have been the source of many court cases, and government attempts at resolution of existing and future cases.

To date, about 100 companies have declared bankruptcy at least partially due to asbestos-related liability. In accordance with Chapter 11 and § 524(g) of the U.S. federal bankruptcy code, a company may transfer its liabilities and certain assets to an asbestos personal injury trust, which is then responsible for compensating present and future claimants. Since 1988, 60 trusts have been established to pay claims with about $37 billion in total assets. From 1988 through 2010, analysis from the United States Government Accountability Office indicates that trusts have paid about 3.3 million claims valued at about $17.5 billion.[28]

Notable cases

Some notable persons who have died from lung fibrosis associated with asbestos include:

- Bernie Banton, social justice advocate

- Nellie Kershaw, first person diagnosed with asbestos-related disease, 1924

- John MacDougall, politician

- Steve McQueen, actor

- Theodore Sturgeon, writer

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Asbestosis symptoms and treatments". NHS Inform. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 "World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines, 2nd Edition—Asbestos" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ↑ Thillai, Muhunthan; Moller, David R.; Meyer, Keith C. (2017). Clinical Handbook of Interstitial Lung Disease. CRC Press. p. PT635. ISBN 9781351650083. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Asbestosis - Pulmonary Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. May 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Asbestosis symptoms and treatments". NHS Inform. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Smedley, Julia; Dick, Finlay; Sadhra, Steven (2013). Oxford Handbook of Occupational Health. OUP Oxford. p. PT165. ISBN 9780191653308. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Asbestosis symptoms and treatments". NHS Inform. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Asbestosis symptoms and treatments". NHS Inform. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 American Thoracic Society (September 2004). "Diagnosis and initial management of nonmalignant diseases related to asbestos". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170 (6): 691–715. doi:10.1164/rccm.200310-1436ST. PMID 15355871. S2CID 16084774.

- ↑ Sporn, Thomas A; Roggli, Victor L.; Oury, Tim D (2004). Pathology of asbestos-associated diseases. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-20090-3.

- ↑ Miller A, Lilis R, Godbold J, Chan E, Selikoff IJ (February 1992). "Relationship of pulmonary function to radiographic interstitial fibrosis in 2,611 long-term asbestos insulators. An assessment of the International Labour Office profusion score". Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 145 (2 Pt 1): 263–70. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_pt_1.263. PMID 1736729.

- ↑ Kilburn KH, Warshaw RH (October 1994). "Airways obstruction from asbestos exposure. Effects of asbestosis and smoking". Chest. 106 (4): 1061–70. doi:10.1378/chest.106.4.1061. PMID 7924474. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22.

- ↑ Roggli VL, Sanders LL (2000). "Asbestos content of lung tissue and carcinoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic correlation and mineral fiber analysis of 234 cases". Ann Occup Hyg. 44 (2): 109–17. doi:10.1016/s0003-4878(99)00067-8. PMID 10717262. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Burdorf A, Swuste P (1999). "An expert system for the evaluation of historical asbestos exposure as diagnostic criterion in asbestos-related diseases". Ann Occup Hyg. 43 (1): 57–66. doi:10.1093/annhyg/43.1.57. PMID 10028894. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ "Asbestos". CDC. October 9, 2013. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Dorsett D. (2015). The Health Effects of Asbestos: An Evidence-based Approach. ISBN 9781498728409. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ↑ Warheit D. B.; Hill L. H.; George G.; Brody A. R. (1986). "Time Course of chemotactic factor generation and the macrophage response to asbestos inhalation". Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 134: 128–133.

- ↑ Liu J.-Y.; Brass D. M.; Hoyle G. W.; Brody A. R. (1998). "TNF-α receptor knockout mice are protected from the fibroproliferative effects of inhaled asbestos fibers". Am. J. Pathol. 153 (6): 1839–1847. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65698-2. PMC 1866331. PMID 9846974.

- ↑ Liu J.-Y.; Sime P. J.; Wu T.; Warshamana G. S.; Pociask D.; Tsai S.-Y.; Brody A. R. (2001). "Transforming Growth Factor-β1 overexpression in Tumor Necrosis Factor-α receptor knockout mice induces fibroproliferative lung disease". Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 25 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1165/ajrcmb.25.1.4481. PMID 11472967.

- ↑ Brody, A. R. Asbestosis. In: Comprehensive Toxicology. (Roth, R. A., Ed.), Elsevier Science, New York, Vol. 8(25), pp. 393–413, 1997.

- ↑ Becklake MR, Case BW (December 1994). "Fiber burden and asbestos-related lung disease: determinants of dose-response relationships". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150 (6 Pt 1): 1488–92. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.6.7952604. PMID 7952604.

- ↑ Craighead JE, Abraham JL, Churg A, et al. (October 1982). "The pathology of asbestos-associated diseases of the lungs and pleural cavities: diagnostic criteria and proposed grading schema. Report of the Pneumoconiosis Committee of the College of American Pathologists and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 106 (11): 544–96. PMID 6897166.

- ↑ Berger, Stephen A.; Castleman, Barry I. (2005). Asbestos: medical and legal aspects. Gaithersburg MD: Aspen. ISBN 978-0-7355-5260-9.

- ↑ Cooke WE (1924-07-26). "Fibrosis of the Lungs due to the Inhalation of Asbestos Dust". Br Med J. 2 (3317): 140–2, 147. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3317.147. PMC 2304688. PMID 20771679.

- ↑ Selikoff, Irving J.; Greenberg, Morris (1991-02-20). "A Landmark Case in Asbestosis" (PDF). JAMA. 265 (7): 898–901. doi:10.1001/jama.265.7.898. PMID 1825122. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- ↑ Report to the Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives Archived 2016-04-06 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved April 30, 2016.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- "Asbestos Toxicity". ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- "Asbestos health and safety". British Government Health and Safety Executive. Archived from the original on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2004-12-17.

- "Asbestos Exposure". National Cancer Institute, USA. 2017-06-15. Archived from the original on 2010-09-26. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

- "Environmental Health Guidance Note — Asbestos" (PDF). Queensland Health. May 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- "Asbestos". IRIS — Integrated Risk Information System. US Environmental Protection Agency. 2013-03-15. CASRN 1332-21-4. Archived from the original on 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2006-10-08.